International relations theory

International relations theory is the study of international relations (IR) from a theoretical perspective. It attempts to provide a conceptual framework upon which international relations can be analyzed.[1] Ole Holsti describes international relations theories as acting like pairs of coloured sunglasses that allow the wearer to see only salient events relevant to the theory; e.g., an adherent of realism may completely disregard an event that a constructivist might pounce upon as crucial, and vice versa. The three most prominent theories are realism, liberalism and constructivism.[2] Sometimes, institutionalism proposed and developed by Keohane and Nye is discussed as a paradigm differed from liberalism.

| International relations theory |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

International relations theories can be divided into "positivist/rationalist" theories which focus on a principally state-level analysis, and "post-positivist/reflectivist" ones which incorporate expanded meanings of security, ranging from class, to gender, to postcolonial security. Many often conflicting ways of thinking exist in IR theory, including constructivism, institutionalism, Marxism, neo-Gramscianism, and others. However, two positivist schools of thought are most prevalent: realism and liberalism.

The study of international relations, as theory, can be traced to E. H. Carr's The Twenty Years' Crisis, which was published in 1939, and to Hans Morgenthau's Politics Among Nations published in 1948.[3] International relations, as a discipline, is believed to have emerged after the First World War with the establishment of a Chair of International Relations, the Woodrow Wilson Chair held by Alfred Eckhard Zimmern[4] at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth.[5]

Early international relations scholarship in the interwar years focused on the need for the balance of power system to be replaced with a system of collective security. These thinkers were later described as "Idealists".[6] The leading critique of this school of thinking was the "realist" analysis offered by Carr.

However, a more recent study, by David Long and Brian Schmidt in 2005, offers a revisionist account of the origins of the field of international relations. They claim that the history of the field can be traced back to late 19th Century imperialism and internationalism. The fact that the history of the field is presented by "great debates", such as the realist-idealist debate, does not correspond with the historic evidence found in earlier works: "We should once and for all dispense with the outdated anachronistic artifice of the debate between the idealists and realists as the dominant framework for and understanding the history of the field". Their revisionist account claims that, up until 1918, international relations already existed in the form of colonial administration, race science, and race development.[7]

A clear distinction is made between explanatory and constitutive approaches when classifying international relations theories.

Realism

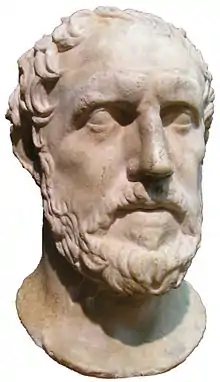

Realism or political realism[9] has been the dominant theory of international relations since the conception of the discipline.[10] The theory claims to rely upon an ancient tradition of thought which includes writers such as Thucydides, Machiavelli, and Hobbes. Early realism can be characterized as a reaction against interwar idealist thinking. The outbreak of World War II was seen by realists as evidence of the deficiencies of idealist thinking. There are various strands of modern-day realist thinking. However, the main tenets of the theory have been identified as statism, survival, and self-help.[10]

- Statism: Realists believe that nation states are the main actors in international politics.[11] As such it is a state-centric theory of international relations. This contrasts with liberal international relations theories which accommodate roles for non-state actors and international institutions. This difference is sometimes expressed by describing a realist world view as one which sees nation states as billiard balls, liberals would consider relationships between states to be more of a cobweb.

- Survival: Realists believe that the international system is governed by anarchy, meaning that there is no central authority.[9] Therefore, international politics is a struggle for power between self-interested states.[12]

- Self-help: Realists believe that no other states can be relied upon to help guarantee the state's survival.

Realism makes several key assumptions. It assumes that nation-states are unitary, geographically based actors in an anarchic international system with no authority above capable of regulating interactions between states as no true authoritative world government exists. Secondly, it assumes that sovereign states, rather than intergovernmental organizations, non-governmental organizations, or multinational corporations, are the primary actors in international affairs. Thus, states, as the highest order, are in competition with one another. As such, a state acts as a rational autonomous actor in pursuit of its own self-interest with a primary goal to maintain and ensure its own security—and thus its sovereignty and survival. Realism holds that in pursuit of their interests, states will attempt to amass resources, and that relations between states are determined by their relative levels of power. That level of power is in turn determined by the state's military, economic, and political capabilities.

Some realists, known as human nature realists or classical realists,[13] believe that states are inherently aggressive, that territorial expansion is constrained only by opposing powers, while others, known as offensive/defensive realists,[13] believe that states are obsessed with the security and continuation of the state's existence. The defensive view can lead to a security dilemma, where increasing one's own security can bring along greater instability as the opponent(s) builds up its own arms, making security a zero-sum game where only relative gains can be made.

Neorealism

Neorealism or structural realism[14] is a development of realism advanced by Kenneth Waltz in Theory of International Politics. It is, however, only one strand of neorealism. Joseph Grieco has combined neo-realist thinking with more traditional realists. This strand of theory is sometimes called "modern realism".[15] Waltz's neorealism contends that the effect of structure must be taken into account in explaining state behavior. It shapes all foreign policy choices of states in the international arena. For instance, any disagreement between states derives from lack of a common power (central authority) to enforce rules and maintain them constantly. Thus there is constant anarchy in international system that makes it necessary for states the obtainment of strong weapons in order to guarantee their survival. Additionally, in an anarchic system, states with greater power have tendency to increase its influence further.[16] According to neo-realists, structure is considered extremely important element in IR and defined twofold as: a) the ordering principle of the international system which is anarchy, and b) the distribution of capabilities across units. Waltz also challenges traditional realism's emphasis on traditional military power, instead characterizing power in terms of the combined capabilities of the state.[17]

Liberalism

.jpg.webp)

The precursor to liberal international relations theory was "idealism". Idealism (or utopianism) was viewed critically by those who saw themselves as "realists", for instance E. H. Carr.[19] In international relations, idealism (also called "Wilsonianism" because of its association with Woodrow Wilson) is a school of thought that holds that a state should make its internal political philosophy the goal of its foreign policy. For example, an idealist might believe that ending poverty at home should be coupled with tackling poverty abroad. Wilson's idealism was a precursor to liberal international relations theory, which would arise amongst the "institution-builders" after World War I.

Liberalism holds that state preferences, rather than state capabilities, are the primary determinant of state behavior. Unlike realism, where the state is seen as a unitary actor, liberalism allows for plurality in state actions. Thus, preferences will vary from state to state, depending on factors such as culture, economic system or government type. Liberalism also holds that interaction between states is not limited to the political/security ("high politics"), but also economic/cultural ("low politics") whether through commercial firms, organizations or individuals. Thus, instead of an anarchic international system, there are plenty of opportunities for cooperation and broader notions of power, such as cultural capital (for example, the influence of films leading to the popularity of the country's culture and creating a market for its exports worldwide). Another assumption is that absolute gains can be made through co-operation and interdependence—thus peace can be achieved.

The democratic peace theory argues that liberal democracies have never (or almost never) made war on one another and have fewer conflicts among themselves. This is seen as contradicting especially the realist theories and this empirical claim is now one of the great disputes in political science. Numerous explanations have been proposed for the democratic peace. It has also been argued, as in the book Never at War, that democracies conduct diplomacy in general very differently from non-democracies. (Neo)realists disagree with Liberals over the theory, often citing structural reasons for the peace, as opposed to the state's government. Sebastian Rosato, a critic of democratic peace theory, points to America's behavior towards left-leaning democracies in Latin America during the Cold War to challenge democratic peace.[20] One argument is that economic interdependence makes war between trading partners less likely.[21] In contrast realists claim that economic interdependence increases rather than decreases the likelihood of conflict.

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism, liberal institutionalism or neo-liberal institutionalism[22] is an advancement of liberal thinking. It argues that international institutions can allow nations to successfully cooperate in the international system.

Complex interdependence

Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, in response to neorealism, develop an opposing theory they dub "complex interdependence." Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye explain, "... complex interdependence sometimes comes closer to reality than does realism."[23] In explaining this, Keohane and Nye cover the three assumptions in realist thought: First, states are coherent units and are the dominant actors in international relations; second, force is a usable and effective instrument of policy; and finally, the assumption that there is a hierarchy in international politics.

The heart of Keohane and Nye's argument is that in international politics there are, in fact, multiple channels that connect societies exceeding the conventional Westphalian system of states. This manifests itself in many forms ranging from informal governmental ties to multinational corporations and organizations. Here they define their terminology; interstate relations are those channels assumed by realists; transgovernmental relations occur when one relaxes the realist assumption that states act coherently as units; transnational applies when one removes the assumption that states are the only units. It is through these channels that political exchange occurs, not through the limited interstate channel as championed by realists.

Secondly, Keohane and Nye argue that there is not, in fact, a hierarchy among issues, meaning that not only is the martial arm of foreign policy not the supreme tool by which to carry out a state's agenda, but that there are a multitude of different agendas that come to the forefront. The line between domestic and foreign policy becomes blurred in this case, as realistically there is no clear agenda in interstate relations.

Finally, the use of military force is not exercised when complex interdependence prevails. The idea is developed that between countries in which a complex interdependence exists, the role of the military in resolving disputes is negated. However, Keohane and Nye go on to state that the role of the military is in fact important in that "alliance's political and military relations with a rival bloc."[24]

Post-liberalism

One version of post-liberal theory argues that within the modern, globalized world, states in fact are driven to cooperate in order to ensure security and sovereign interests. The departure from classical liberal theory is most notably felt in the re-interpretation of the concepts of sovereignty and autonomy. Autonomy becomes a problematic concept in shifting away from a notion of freedom, self-determination, and agency to a heavily responsible and duty laden concept. Importantly, autonomy is linked to a capacity for good governance. Similarly, sovereignty also experiences a shift from a right to a duty. In the global economy, International organizations hold sovereign states to account, leading to a situation where sovereignty is co-produced among "sovereign" states. The concept becomes a variable capacity of good governance and can no longer be accepted as an absolute right. One possible way to interpret this theory, is the idea that in order to maintain global stability and security and solve the problem of the anarchic world system in International Relations, no overarching, global, sovereign authority is created. Instead, states collectively abandon some rights for full autonomy and sovereignty.[25] Another version of post-liberalism, drawing on work in political philosophy after the end of the Cold War, as well as on democratic transitions in particular in Latin America, argues that social forces from below are essential in understanding the nature of the state and the international system. Without understanding their contribution to political order and its progressive possibilities, particularly in the area of peace in local and international frameworks, the weaknesses of the state, the failings of the liberal peace, and challenges to global governance cannot be realised or properly understood. Furthermore, the impact of social forces on political and economic power, structures, and institutions, provides some empirical evidence of the complex shifts currently underway in IR.[26]

Constructivism

Constructivism or social constructivism[29] has been described as a challenge to the dominance of neo-liberal and neo-realist international relations theories.[30] Michael Barnett describes constructivist international relations theories as being concerned with how ideas define international structure, how this structure defines the interests and identities of states and how states and non-state actors reproduce this structure.[31] The key element of constructivism is the belief that "International politics is shaped by persuasive ideas, collective values, culture, and social identities." Constructivism argues that international reality is socially constructed by cognitive structures which give meaning to the material world.[32] The theory emerged from debates concerning the scientific method of international relations theories and theories role in the production of international power.[33] Emanuel Adler states that constructivism occupies a middle ground between rationalist and interpretative theories of international relations.[32]

Constructivist theory criticises the static assumptions of traditional international relations theory and emphasizes that international relations is a social construction. Constructivism is a theory critical of the ontological basis of rationalist theories of international relations.[34] Whereas realism deals mainly with security and material power, and liberalism looks primarily at economic interdependence and domestic-level factors, constructivism most concerns itself with the role of ideas in shaping the international system; indeed it is possible there is some overlap between constructivism and realism or liberalism, but they remain separate schools of thought. By "ideas" constructivists refer to the goals, threats, fears, identities, and other elements of perceived reality that influence states and non-state actors within the international system. Constructivists believe that these ideational factors can often have far-reaching effects, and that they can trump materialistic power concerns.

For example, constructivists note that an increase in the size of the U.S. military is likely to be viewed with much greater concern in Cuba, a traditional antagonist of the United States, than in Canada, a close U.S. ally. Therefore, there must be perceptions at work in shaping international outcomes. As such, constructivists do not see anarchy as the invariable foundation of the international system,[35] but rather argue, in the words of Alexander Wendt, that "anarchy is what states make of it".[36] Constructivists also believe that social norms shape and change foreign policy over time rather than security which realists cite.

Marxism

Marxist and Neo-Marxist international relations theories are structuralist paradigms which reject the realist/liberal view of state conflict or cooperation; instead focusing on the economic and material aspects. Marxist approaches argue the position of historical materialism and make the assumption that the economic concerns transcend others; allowing for the elevation of class as the focus of study. Marxists view the international system as an integrated capitalist system in pursuit of capital accumulation. A sub-discipline of Marxist IR is Critical Security Studies. Gramscian approaches rely on the ideas of Italian Antonio Gramsci whose writings concerned the hegemony that capitalism holds as an ideology. Marxist approaches have also inspired Critical Theorists such as Robert W. Cox who argues that "Theory is always for someone and for some purpose".[37]

One notable Marxist approach to international relations theory is Immanuel Wallerstein's World-system theory which can be traced back to the ideas expressed by Lenin in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. World-system theory argues that globalized capitalism has created a core of modern industrialized countries which exploit a periphery of exploited "Third World" countries. These ideas were developed by the Latin American Dependency School. "Neo-Marxist" or "New Marxist" approaches have returned to the writings of Karl Marx for their inspiration. Key "New Marxists" include Justin Rosenberg and Benno Teschke. Marxist approaches have enjoyed a renaissance since the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe.

Criticisms of Marxists approaches to international relations theory include the narrow focus on material and economic aspects of life.

Green theory

Green theory in international relations is a sub-field of international relations theory which concerns international environmental cooperation.

Alternative approaches

Several alternative approaches have been developed based on foundationalism, anti-foundationalism, positivism, behaviouralism, structuralism and post-structuralism. These theories however are not widely known.

Behaviouralism in international relations theory is an approach to international relations theory which believes in the unity of science, the idea that the social sciences are not fundamentally different from the natural sciences.[38]

English School

The "English School" of international relations theory, also known as International Society, Liberal Realism, Rationalism or the British institutionalists, maintains that there is a 'society of states' at the international level, despite the condition of "anarchy", i.e., the lack of a ruler or world state. Despite being called the English School many of the academics from this school were neither English nor from the United Kingdom.

A great deal of the work of the English School concerns the examination of traditions of past international theory, casting it, as Martin Wight did in his 1950s-era lectures at the London School of Economics, into three divisions:

- Realist (or Hobbesian, after Thomas Hobbes), which views states as independent competing units

- Rationalist (or Grotian, after Hugo Grotius), which looks at how states can work together and cooperate for mutual benefit

- Revolutionist (or Kantian, after Immanuel Kant), which looks at human society as transcending borders or national identities

In broad terms, the English School itself has supported the rationalist or Grotian tradition, seeking a middle way (or via media) between the power politics of realism and the "utopianism" of revolutionism. The English School rejects behavioralist approaches to international relations theory.

One way to think about the English School is that, while some theories identify with just one of the three historical traditions (Classical Realism and Neorealism owe a debt to the Realist or Hobbesian tradition; Marxism to the Revolutionist tradition, for example), English School looks to combine all of them. While there is great diversity within the 'school', much of it involves either examining when and how the different traditions combine or dominate, or focusing on the Rationalist tradition, especially the concept of International Society (which is the concept most associated with English School thinking).

In Hedley Bull's The Anarchical Society, a seminal work of the school, he begins by looking at the concept of order, arguing that states across time and space have come together to overcome some of the danger and uncertainty of the Hobbesian international system to create an international society of states that share certain interests and ways of thinking about the world. By doing so, they make the world more ordered, and can eventually change international relations to become significantly more peaceful and beneficial to their shared interests.

Functionalism

Functionalism is a theory of international relations that arose principally from the experience of European integration. Rather than the self-interest that realists see as a motivating factor, functionalists focus on common interests shared by states. Integration develops its own internal dynamic: as states integrate in limited functional or technical areas, they increasingly find that momentum for further rounds of integration in related areas. This "invisible hand" of integration phenomenon is termed "spillover". Although integration can be resisted, it becomes harder to stop integration's reach as it progresses. This usage, and the usage in functionalism in international relations, is the less common meaning of functionalism.

More commonly, however, functionalism is an argument that explains phenomena as functions of a system rather than an actor or actors. Immanuel Wallerstein employed a functionalist theory when he argued that the Westphalian international political system arose to secure and protect the developing international capitalist system. His theory is called "functionalist" because it says that an event was a function of the preferences of a system and not the preferences of an agent. Functionalism is different from structural or realist arguments in that while both look to broader, structural causes, realists (and structuralists more broadly) say that the structure gives incentives to agents, while functionalists attribute causal power to the system itself, bypassing agents entirely.

Post-structuralism

Post-structuralism differs from most other approaches to international politics because it does not see itself as a theory, school or paradigm which produces a single account of the subject matter. Instead, post-structuralism is an approach, attitude, or ethos that pursues critique in particular way. Post-structuralism sees critique as an inherently positive exercise that establishes the conditions of possibility for pursuing alternatives. It states that "Every understanding of international politics depends upon abstraction, representation and interpretation". Scholars associated with post-structuralism in international relations include Richard K. Ashley, James Der Derian, Michael J. Shapiro, R. B. J. Walker,[39] and Lene Hansen.

Post-modernism

Post-modernist approaches to international relations are critical of metanarratives and denounces traditional IR's claims to truth and neutrality.[40]

Postcolonialism

Postcolonial International relations scholarship posits a critical theory approach to International relations (IR), and is a non-mainstream area of international relations scholarship. Post-colonialism focuses on the persistence of colonial forms of power and the continuing existence of racism in world politics.[41]

Feminist international relations theory

Feminist international relations theory applies a gender perspective to topics and themes in international relations such as war, peace, security, and trade. In particular, feminist international relations scholars use gender to analyze how power exists within different international political systems. Historically, feminist international relations theorists have struggled to find a place within international relations theory, either having their work ignored or discredited.[42] Feminist international relations also analyzes how the social and the political interact, often pointing to the ways in which international relations affect individuals and vice versa. Generally, feminist international relations scholars tend to be critical of the realist school of thought for their strong positivist and state-centered approach to international relations, although feminist international scholars who are also realists exist.[42] Feminist International Relations borrows from a number of methodologies and theories such as post-positivism, constructivism, postmodernism, and post-colonialism.

Jean Bethke Elshtain is a key contributer to feminist international relations theory. In her seminal book, Women and War, Elshtain criticizes gender roles inherent in mainstream international relations theory. Particularly, Elshtain decries international relations for perpetuating a tradition of armed civic culture that automatically excludes women/wives.[43] Instead, Elshatin challenges the trope of women as solely passive peacekeepers, using drawing parallels between wartime experiences and her personal experiences from her childhood and later as a mother.[43] Thus, Elshtain has been lauded by some feminist international relations theorists as one of the first theorists to blend personal experience with international relations, thus challenging international relation’s traditional preference for positivism.[43]

Cynthia Enloe is another influential scholar in the field of feminist international relations. Her influential feminist international relations text, Bananas, Beaches, and Bases, considers where women fit into the international political system.[43] Similar to Jean Bethke Elshtain, Enloe looks at how the everyday lives of women are influenced by international relations.[43] For example, Enloe uses banana plantations to illustrate how different women are affected by international politics depending on their geographical location, race, or ethnicity.[43] Women, Enloe argues, play a role in international relations whether this work is recognized or not, working as labourers, wives, sex workers, and mothers, sometimes within army bases.[43]

J. Ann Tickner is a prominent feminist international relations theorist with many notable written pieces. For example, her piece "You Just Don’t Understand: Troubled Engagements Between Feminists and IR Theorists" examines the misunderstandings that occur between feminist scholars and international relations theorists. Specifically, Tickner argues that feminist international relations theory sometimes works outside of traditional ontological and epistemological international relations structures, instead analyzing international relations from a more humanistic perspective.[42] Thus, Tickner was critical of the ways in which the study of international relations itself excludes women from participating in international relations theorizing. This piece of Tickner’s was met with criticism from multiple scholars, such as Robert Keohane, who wrote “Beyond Dichotomy: Conversations Between International Relations and Feminist Theory”[44] and Marianne Marchand, who criticized Tickner’s assumption that feminist international relations scholars worked in the same ontological reality and epistemological tradition in her piece “Different Communities/Different Realities/Different Encounters”.[45]

Evolutionary perspectives

Evolutionary perspectives, such as from evolutionary psychology, have been argued to help explain many features of international relations.[46] Humans in the ancestral environment did not live in states and likely rarely had interactions with groups outside of a very local area. However, a variety of evolved psychological mechanisms, in particular those for dealing with inter group interactions, are argued to influence current international relations. These include evolved mechanisms for social exchange, cheating and detecting cheating, status conflicts, leadership, ingroup and outgroup distinction and biases, coalitions, and violence. Evolutionary concepts such as inclusive fitness may help explain seeming limitations of a concept such as egotism which is of fundamental importance to realist and rational choice international relations theories.[47][48]

Neuroscience and IR

In recent years, with significant advances in neuroscience and neuroimaging tools, IR Theory has benefited from further multidisciplinary contributions. Prof. Nayef Al-Rodhan from Oxford University has argued that neuroscience[49] can significantly advance the IR debate as it brings forward new insights about human nature, which is at the centre of political theory. New tools to scan the human brain, and studies in neurochemistry allow us to grasp what drives divisiveness,[50] conflict, and human nature in general. The theory of human nature in Classical Realism, developed long before the advent of neuroscience, stressed that egoism and competition were central to human behaviour, to politics and social relations. Evidence from neuroscience, however, provides a more nuanced understanding of human nature, which Prof. Al-Rodhan describes as emotional amoral egoistic. These three features can be summarized as follows: 1. emotionality is more pervasive than rationality and central to decision-making, 2. we are born neither moral, nor immoral but amoral, and circumstances decide how our moral compass will develop, and finally, 3. we are egoistic insofar as we seek to ensure our survival, which is a basic form of egoism. This neurophilosophy of human nature can also be applied to states[51] - similarly to the Realist analogy between the character (and flaws) of man and the state in international politics. Prof Al-Rodhan argues there are significant examples in history and contemporary politics that demonstrate states behave less rationality than IR dogma would have us believe: different strategic cultures, habits,[52] identity politics influence state conduct, geopolitics and diplomacy in profound ways.

Theory in international relations scholarship

Several IR scholars bemoan what they see as a trend away from IR theory in IR scholarship.[53][54][55][56][57] The September 2013 issue of European Journal of International Relations and the June 2015 issue of Perspectives on Politics debated the state of IR theory.[58][59] A 2016 study showed that while theoretical innovations and qualitative analyses are a large part of graduate training, journals favor middle-range theory, quantitative hypothesis testing and methodology for publishing.[60]

See also

References

- "The IR Theory Home Page". Irtheory.com. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- Snyder, Jack, 'One World, Rival Theories, Foreign Policy, 145 (November/December 2004), p.52

- Burchill, Scott and Linklater, Andrew "Introduction" Theories of International Relations, ed. Scott Burchill ... [et al.], p.1. Palgrave, 2005.

- Abadía, Adolfo A. (2015). "Del liberalismo al neo-realismo. Un debate en torno al realismo clásico" [From Liberalism to Neorealism. A Discussion Around Classical Realism] (PDF). Telos. Revista de Estudios Interdisciplinarios en Ciencias Sociales (in Spanish). 17 (3): 438–459. ISSN 1317-0570. SSRN 2810410.

- Burchill, Scott and Linklater, Andrew "Introduction" Theories of International Relations, ed. Scott Burchill ... [et al.], p.6. Palgrave, 2005.

- Burchill, Scott and Linklater, Andrew "Introduction" Theories of International Relations, ed. Scott Burchill ... [et al.], p.7. Palgrave, 2005.

- Schmidt, Brian; Long, David (2005). Imperialism and Internationalism in the Discipline of International Relations. New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791463239.

- See Forde, Steven,(1995), 'International Realism and the Science of Politics:Thucydides, Machiavelli and Neorealism,' International Studies Quarterly 39(2):141–160

- "Political Realism | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Iep.utm.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- Dunne, Tim and Schmidt, Britain, The Globalisation of World Politics, Baylis, Smith and Owens, OUP, 4th ed, p

- Snyder, Jack, 'One World, Rival Theories, Foreign Policy, 145 (November/December 2004), p.59

- Snyder, Jack, 'One World, Rival Theories, Foreign Policy, 145 (November/December 2004), p.55

- Mearsheimer, John (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-393-07624-0.

- "Structural Realism" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 17, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- Lamy,Steven, Contemporary Approaches:Neo-realism and neo-liberalism in "The Globalisation of World Politics, Baylis, Smith and Owens, OUP, 4th ed,p127

- The Globalization of World Politics. Oxford University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-19-929777-1.

- Lamy, Steven, "Contemporary mainstream approaches: neo-realism and neo-liberalism", The Globalisation of World Politics, Smith, Baylis and Owens, OUP, 4th ed, pp.127–128

- E Gartzk, Kant we all just get along? Opportunity, willingness, and the origins of the democratic peace, American Journal of Political Science, 1998

- Brian C. Schmidt, The political discourse of anarchy: a disciplinary history of international relations, 1998, p.219

- Rosato, Sebastian, The Flawed Logic of Democratic Peace Theory, American Political Science Review, Volume 97, Issue 04, November 2003, pp.585–602

- Copeland, Dale, Economic Interdependence and War: A Theory of Trade Expectations, International Security, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Spring, 1996), pp.5–41

- Sutch, Peter, Elias, 2006, Juanita, International Relations: The Basics, Routledge p.11

- Keohane, Robert O.; Nye, Joseph S. (1997). "Realism and Complex Interdependence". In Crane, George T.; Amawi, Abla (eds.). The Theoretical Evolution of International Political Economy: A Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-19-509443-5.

- Keohane & Nye 1997, p. 134.

- Chandler, David (2010). International Statebuilding – The Rise of the Post-Liberal Paradigm. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. pp. 43–90. ISBN 978-0-415-42118-8.

- Richmond, Oliver (2011). A Post-Liberal Peace. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-66784-5.

- Stephen M. Walt, Foreign Policy, No. 110, Special Edition: Frontiers of Knowledge. (Spring, 1998), p.41: "The end of the Cold War played an important role in legitimizing constructivist t realism and liberalism failed to anticipate this event and had trouble explaining it.

- Hay, Colin (2002) Political Analysis: A Critical Introduction, Basingstoke: Palgrave, P. 198

- Richard Jackson (November 21, 2008). "Ch 6: Social Constructivism". Introduction to International Relations 3e (PDF). Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-04-23.

- Hopf, Ted, The Promise of Constructivism in International Relations Theory, International Security, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Summer, 1998), p.171

- Michael Barnett, "Social Constructivism" in The Globalisation of World Politics, Baylis, Smith and Owens, 4th ed, OUP, p.162

- Alder, Emmanuel, Seizing the middle ground, European Journal of International Relations, Vol .3, 1997, p.319

- K.M. Ferike, International Relations Theories:Discipline and Diversity, Dunne, Kurki and Smith, OUP, p.167

- In international relations ontology refers to the basic unit of analysis that an international relations theory uses. For example for neorealists humans are the basic unit of analysis

- "The IR Theory Knowledge Base". Irtheory.com. 2015-04-03. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- Wendt, Alexander, "Anarchy is what states make of it: the social construction of power politics" in International Organization, vol. 46, no. 2, 1992

- Cox, Robert, Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory Cox Millennium – Journal of International Studies.1981; 10: 126–155

- Jackson, Robert, Sorensen, Georg, “Introduction to International Relations: Theories and Approaches", OUP, 3rd ed, p305

- "Dunne, Kurki & Smith: International Relations Theories 4e: Chapter 11: Revision guide". Oxford University Press Online Resource Centre. Oxford University Press. 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2011-07-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Baylis, Smith and Owens, The Globalisation of World Politics, OUP, 4th ed, p187-189

- Tickner, J. Ann (December 1997). "You Just Don't Understand: Troubled Engagements Between Feminists and IR Theorists". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (4): 611–632. doi:10.1111/1468-2478.00060. hdl:1885/41080. ISSN 0020-8833.

- "Introducing Elshtain, Enloe, and Tickner: looking at key feminist efforts before journeying on", Feminist International Relations, Cambridge University Press, pp. 18–50, 2001-12-20, ISBN 978-0-521-79627-9, retrieved 2021-02-04

- Keohane, Robert O. (March 1998). "Beyond Dichotomy: Conversations Between International Relations and Feminist Theory". International Studies Quarterly. 42 (1): 193–197. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00076. ISSN 0020-8833.

- Marchand, Marianne (1998). "Different Communities / Different Realities / Different Encounters: A Reply to J. Ann Tickner". International Relations Quarterly. 42: 199–204 – via JSTOR.

- McDermott, Rose; Davenport, Christian (2017-01-25). "Toward an Evolutionary Theory of International Relations". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.294. ISBN 9780190228637.

- Bradley A. Thayer. Darwin and International Relations: On the Evolutionary Origins of War and Ethnic Conflict. 2004. University Press of Kentucky.

- Bradley A. Thayer (2010). "Darwin and International Relations Theory: Improving Theoretical Assumptions of Political Behavior" (PDF). Psa.ac.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-06. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

Prepared for Presentation at the 60th Political Studies Association Annual Conference Edinburgh, Scotland

- "Neuro-philosophy of International Relations | Nayef Al-Rodhan". Themontrealreview.com. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- Nayef Al-Rodhan (2016-10-19). "Us versus Them. How neurophilosophy explains our divided politics - OxPol". Blog.politics.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- Nayef Al-Rodhan (2016-10-19). "The emotional amoral egoism of states - OxPol". Blog.politics.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- Hopf, Ted (2010). "European Journal of International Relations : The logic of habit in International Relations". European Journal of International Relations. 16 (4): 539–561. doi:10.1177/1354066110363502. S2CID 145467874.

- Mearsheimer, John J.; Walt, Stephen M. (2013-09-01). "Leaving theory behind: Why simplistic hypothesis testing is bad for International Relations". European Journal of International Relations. 19 (3): 427–457. doi:10.1177/1354066113494320. ISSN 1354-0661. S2CID 52247884.

- Aggarwal, Vinod K. (2010-09-01). "I Don't Get No Respect:1 The Travails of IPE2". International Studies Quarterly. 54 (3): 893–895. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00615.x. ISSN 1468-2478.

- Keohane, Robert O. (2009-02-16). "The old IPE and the new". Review of International Political Economy. 16 (1): 34–46. doi:10.1080/09692290802524059. ISSN 0969-2290. S2CID 155053518.

- Desch, Michael (2015-06-01). "Technique Trumps Relevance: The Professionalization of Political Science and the Marginalization of Security Studies". Perspectives on Politics. 13 (2): 377–393. doi:10.1017/S1537592714004022. ISSN 1541-0986.

- Isaac, Jeffrey C. (2015-06-01). "For a More Public Political Science". Perspectives on Politics. 13 (2): 269–283. doi:10.1017/S1537592715000031. ISSN 1541-0986.

- "Table of Contents — September 2013, 19 (3)". ejt.sagepub.com. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- "Perspectives on Politics Vol. 13 Issue 02". journals.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2016-02-17.

- Colgan, Jeff D. (2016-02-12). "Where Is International Relations Going? Evidence from Graduate Training". International Studies Quarterly. 60 (3): 486–498. doi:10.1093/isq/sqv017. ISSN 0020-8833.

Further reading

- Baylis, John; Steve Smith; and Patricia Owens. (2008) The Globalisation of World Politics, OUP, 4th edition.

- Braumoeller, Bear. (2013) The Great Powers and the International System: Systemic Theory in Empirical Perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Burchill, et al. eds. (2005) Theories of International Relations, 3rd edition, Palgrave, ISBN 1-4039-4866-6

- Chernoff, Fred. Theory and Meta-Theory in International Relations: Concepts and Contending Accounts, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guilhot Nicolas, ed. (2011) The Invention of International Relations Theory: Realism, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the 1954 Conference on Theory.

- Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society, Columbia University Press.

- Jackson, Robert H., and Georg Sørensen (2013) Introduction to International Relations: Theories and Approaches, Oxford, OUP, 5th ed.

- Morgenthau, Hans. Politics Among Nations

- Pettman, Ralph (2010) World Affairs. An Analytical Overview, World Scientific Publishing Company, ISBN 9814293873.

- Waltz, Kenneth. Theory of International Politics

- Waltz, Kenneth. Man, the State, and War, Columbia University Press.

- Weber, Cynthia. (2004) International Relations Theory. A Critical Introduction, 2nd edition, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-34208-2

- Wendt, Alexander. Social Theory of International Politics, Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Theory Talks Interviews with key IR theorists

- The Martin Institute

- A Discussion and Overview of IR Theory and its Historical Roots at American University

- Jack Snyder's 'One World, Rival Theories' in Foreign Policy

- Stephen Walt's 'One World, Many Theories' in Foreign Policy