Political history of the world

The political history of the world is the history of the various political entities created by the human race throughout their existence and the way these states define their borders. Throughout history, political entities have expanded from basic systems of self-governance and monarchy to the complex democratic and totalitarian systems that exist today. In parallel, political systems have expanded from vaguely defined frontier-type boundaries, to the national definite boundaries existing today.

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

Prehistoric era

The first forms of human social organization were families living in band societies as hunter-gatherers.[1]

After the invention of agriculture around the same time (7,000-8,000 BCE) across various parts of the world, human societies started transitioning to tribal forms of organization.[2]

There is evidence of diplomacy between different tribes, but also of endemic warfare.[3] This could have been caused by theft of livestock or crops, abduction of women, or resource and status competition.[4]

Ancient history

The early distribution of political power was determined by the availability of fresh water, fertile soil, and temperate climate of different locations.[5] These were all necessary for the development of highly organized societies.[5] The first empires were those of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.[5] Smaller kingdoms existed in North China Plain, Indo-Gangetic Plain, Central Asia, Anatolia, Eastern Mediterranean, and Central America, while the rest of humanity continued to live in small tribes.[5] Both Egypt and Mesopotamia had been able to take advantage of their large rivers with irrigation systems, enabling higher productivity in agriculture and thereby sustaining surpluses and population growth.[6]

Middle East and the Mediterranean

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the Uruk period and Predynastic Egypt respectively at approximately 3000BCE.[7] Early dynastic Egypt was based around the Nile River in the north-east of Africa, the kingdom's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where oases existed.[8] Upper and Lower Egypt were unified around 3150 BCE by Pharaoh Menes.[6] Nevertheless, political competition continued within the country between centers of power such as Memphis and Thebes.[6] The geopolitical environment of the Egyptians had them surrounded by Nubia in the smaller southern oases of the Nile unreachable by boat, as well as by Libyan warlords operating from the oases around modern-day Benghazi, and finally by raiders across the Sinai and the sea.[9]

Mesopotamian dominance

Mesopotamia is situated between the major rivers of Tigris and Euphrates, and the first political power in the region was the Akkadian Empire starting around 2300 BCE.[10] They were later followed by Sumer, Babylon, and Assyria. They faced competition from the mountainous areas to the north, strategically positioned above the Mesopotamian plains, with kingdoms such as Mitanni, Urartu, Elam, and Medes.[10] The Mesopotamians also innovated in governance by writing the first laws.[10]

A dry climate in the Iron Age caused turmoil as movements of people put pressure on the existing states resulting in the Late Bronze Age collapse, with Cimmerians, Arameans, Dorians, and the Sea Peoples migrating among others.[11] Babylon never recovered following the death of Hammurabi in 1699 BCE.[11] Following this, Assyria grew in power under Adad-nirari II.[12] By the late ninth century BCE, the Assyrian Empire controlled almost all of Mesopotamia and much of the Levant and Anatolia.[13] Meanwhile, Egypt was weakened, eventually breaking apart after the death of Osorkon II until 710 BCE.[14] In 853, the Assyrians fought and won a battle against a coalition of Babylon, Egypt, Persia, Israel, Aram, and ten other nations, with over 60,000 troops taking part according to contemporary sources.[15] However, the empire was weakened by internal struggles for power, and was plunged into a decade of turmoil beginning with a plague in 763 BCE.[15] Following revolts by cities and lesser kingdoms against the empire, a coup d'état was staged in 745 by Tiglath-Pileser III.[16] He raised the army from 44,000 to 72,000, followed by his successor Sennacherib who raised it to 208,000, and finally by Ashurbanipal who raised an army of over 300,000.[17] This allowed the empire to spread over Cyprus, the entire Levant, Phrygia, Urartu, Cimmerians, Persia, Medes, Elam, and Babylon.[17]

Persian dominance

By 650, Assyria had started declining as a severe drought hit the Middle East and an alliance was formed against them.[18] Eventually they were replaced by the Median empire as the main power of the region following the Battle of Carchemish (605) and the Battle of the Eclipse (585).[19] The Medians served as the launching pad for the rise of the Persian Empire.[20] After first serving as vassals, under the third Persian king Cambyses I their influence rose, and in 553 they rose against the Medians.[20] By the death of Cyrus the Great, the Persian Achaemenid Empire reached from Aegean Sea to Indus River and Caucasus to Nubia.[21] The empire was divided into provinces ruled by satraps, who collected taxes and were typically local power brokers.[22] The empire controlled about a third of the world's farm land and a quarter of its population.[23] In 522, after King Cambyses II's death, Darius the Great took over power.[24]

Greek dominance

As the population of Ancient Greece grew, they began a colonization of the Mediterranean region.[25] This encouraged trade, which in turn caused political changes in the city-states with old elites being overthrown in Corinth in 657 and in Athens in 632, for example.[26] There were many wars between the cities as well, including the Messenian Wars (743-742; 685-668), the Lelantine War (710-650), and the First Sacred War (595-585).[27] In the seventh and sixth centuries, Corinth and Sparta were the dominant powers of Greece.[28] The former was eventually supplanted by Athens as the main sea power, while Sparta remained the dominant land-force.[29] In 499, in the Ionian Revolt Greek cities in Asia Minor rebelled against the Persian Empire but were crushed in the Battle of Lade.[30] After this, the Persians invaded the Greek mainland in the Greco-Persian Wars (499-449).[31]

The Macedonian King Philip II (350-336) conquered much of Greece.[32] In 338, he formed the League of Corinth to liberate Greeks in Asia Minor from the Persians, with 10,000 troops invading in 336.[33] After his murder, his son Alexander the Great took charge and crossed the Dardanelles in 334.[34] After Asia Minor had been conquered, Alexander invaded Levant, Egypt, and Mesopotamia, defeating the Persians under Darius the Great in the Battle of Gaugamela in 331, and ending the last resistance by 328.[34] After Alexander's death in Babylon in 323, the empire had no designated successor.[35] This led to its division into four: the Antigonid dynasty in Macedonia, the Attalid dynasty in Anatolia, the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt, and the Seleucid Empire over Mesopotamia.[36]

Roman dominance

Rome became dominant in the Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC after defeating the Samnites, the Gauls and the Etruscans for control of the Italian Peninsula.[37] In 264, it challenged its main rival Carthage to a fight for Sicily, starting the Punic Wars.[38] A truce was signed in 241, with Rome gaining Corsica and Sardinia in addition to Sicily.[38] In 218, the Carthaginian general Hannibal marched out of Spain towards Italy, crossing the Alps with his war elephants.[39] After 15 years of fighting, the Romans beat him and then sent troops against Carthage itself, defeating it in 202.[40] The Second Punic War alone cost Rome 100,000 casualties.[41] In 146, Carthage was finally destroyed completely.[42]

Rome suffered from various internal disturbances and destabilities. In 133, Tiberius Gracchus was killed alongside hundreds of supporters after trying to redistribute public land to the poor.[43] The Social War (91-88) was caused by neighbouring cities trying to secure themselves the benefist of Roman citizenship.[43] In 82, general Sulla captured power violently, ending the Roman Republic and becoming a dictator.[44] Following his death new ower struggles emrged, and in Caesar's Civil War (49-46), Julius Caesar and Pompey fought over the empire, with the former winning.[45] After the ruler was assassinated in 44, a second civil war broke out between his potential heirs, Mark Antony and Augustus, the latter becoming emperor.[45] This then led to the Pax Romana, a long period of peace in the empire.[46] The quarrels between the Ptolemaic Kingdom, the Seleucid Empire, the Parthian Empire and the Kingdom of Pontus in the Near East allowed the Romans to expand up to the Euphrates.[47] During Augustus' reign the Rhine, Danube, and the Sahara became the other borders of the empire.[48] The population reached about 60 million.[49]

Political instability in Rome grew. Emperor Caligula (37-41) was murdered by the Praetorian Guard to replace him with Claudius (41-53), while his successor Nero (54-68) burned Rome down.[50] The average reign from his death to Philip the Arab (244-249) was six years.[50] Nevertheless, external expansion continued, with Trajan (98-117) invading Dacia, Parthia and Arabia.[51] Its only formidable enemy was the Parthian Empire.[52] Migrating peoples started exerting pressure on the borders of the empire.[53] The drying climate of Central Asia forced the Huns to move, and in 370 they crossed Don and soon after the Danube, forcing the Goths on the move, which in turn caused other Germanic tribes to overrun Roman borders.[54] In 293, Diocletian (284-305) appointed three rulers for different parts of the empire.[55] It was formally divided in 395 by Theodosius I (379-395) into the Western Roman and Byzantine Empires.[56] In 406 the northern border of the former was overrun by the Alemanni, Vandals and Suebi invaded.[57] In 408 the Visigoths invaded Italy and then sacked Rome in 410.[57] The final collapse of the Western Empire came in 476 with the deposal of Romulus Augustulus (475-476).[58]

Indian subcontinent

Build around the Indus River, by 2500 BCE the Indus Valley Civilization, located in modern-day India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, had formed. The civilization's boundaries extended to 600 km from the Arabian Sea.[59] After its cities Mohenjo-daro and Harappa were abandoned around 1900 BCE, no political power replaced it.[60]

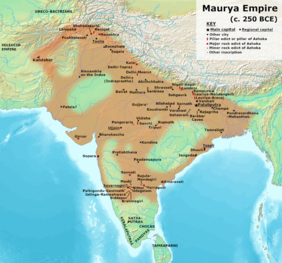

States began to form in the 6th century BCE with the Mahajanapadas.[61] Out of sixteen such states, four strong ones emerged: Kosala, Magadha, Vatsa, and Avanti, with Magadha dominating the rest by the mid-fifth century.[62] The Magadha then transformed into the Nanda Empire under Mahapadma Nanda (345-321), extending from the Gangetic plains to the Hindu Kush and the Deccan Plateau.[63] The empire was, however, overtaken by Chandragupta Maurya (324-298), turning it into the Maurya Empire.[63] He defended against Alexander's invasion from the West and received control of the Hindu Kush mountain passes in a peace treaty signed in 303.[63] By the time of his grandson Ashoka's rule, the empire stretched from Zagros Mountains to the Brahmaputra River.[64] The empire contained a population of 50 to 60 million, governed by a system of provinces ruled by governor-princes, with a capital in Pataliputra.[65]

After Ashoka's death, the empire had begun to decline, with Kashmir in the north, Shunga and Satavahana in the centre, and Kalinga as well as Pandya in the south becoming independent.[66] In to this power vacuum, the Yuezhi were able to establish the new Kushan Empire in 30 CE.[67] The Gupta Empire was founded by Chandragupta I (320-335), which in sixty years expanded from the Ganges to the Bay of Bengal and the Indus River following the downfall of the Kushan Empire.[68] Gupta governance was similar to that of the Maurya.[69] Following wars with the Hephthalites and other problems, the empire fell by 550.[70]

China

In the North China Plain, the Yellow River allowed the rise of states such as Wei and Qi.[71] This area was first unified by the Shang dynasty around 1600 BCE, and replaced by the Zhou dynasty in the Battle of Muye in 1046 BCE, with reportedly millions taking part in the fighting.[71] The victors were however hit by internal unrest soon after.[72] The main rivals of the Zhou were the Dongyi in Shandong, the Xianyun in Ordos, the Guifang in Shanxi, as well as the Chu in the middle reaches of the Yangtze.[73]

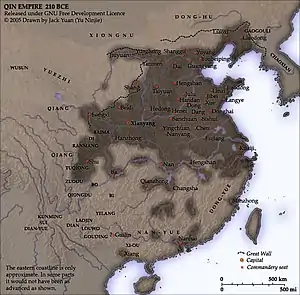

Starting in the eight century, China fell into a state of anarchy for five centuries, during the Spring and Autumn (771-476) and Warring States periods (476-221).[74] During the latter period, the Jin dynasty split into the Wei, Zhao and Han states, while the rest of the North China Plain was composed of the Chu, Qin, Qi and Yan states, while the Zhou remained in the centre with largely ceremonial power.[75] While the Zhao had an advantage at first, the Qin ended up defeating them in 260 with about half a million soldiers fighting on each side at the Battle of Changping.[76] The other states tried to form an alliance against the Qin but were defeated.[77] In 221, the Qin dynasty was established with a population of about 40 million, with a capital of 350,000 in Linzi.[78] Under the leadership of Qin Shi Huang, the dynasty initiated reforms such as establishing territorial administrative units, infrastructure projects (including the Great Wall of China) and uniform Chinese characters.[79] However, after his death and burial with the Terracotta Army, the empire started falling apart when the Chu and Han started fighting over a power vacuum left by a weak heir, with the Han dynasty rising to power in 204 BCE.[80]

Under the Han, the population of China rose to 50 million, with 400,000 in the capital Chang'an, and with territorial expansion to Korea, Vietnam and Tien Shan.[81] Expeditions were also sent against the Xiongnu and to secure the Hexi Corridor, the Nanyue kingdom was annexed, and Hainan and Taiwan conquered.[82] The Chinese pressure on the Xiongnu forced them towards the west, leading to the exodus of the Yuezhi, who in turn pillaged the capital of Bactria.[83] This then led to their new Kushan Empire.[67] The end of the Han dynasty came following internal upheavals in 220 CE, with its split into the Shu, Wu and Wei states.[84] Despite the rise of the Jin dynasty (266–420), China was soon invaded by the Xiongnu in the rebellion of the Five Barbarians (304-316), who conquered large areas of the Northern China plain and declared the Northern Wei in 399.[85]

Americas

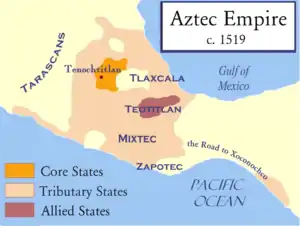

The Olmecs were the first major Indigenous American culture, with some smaller ones such as the Chavín culture amongst mainly hunter-gatherers.[86] The Olmecs were limited by the dense forests and the long rainy season, as well as the lack of horses.[87]

Post-classical era

Asia

When China entered the Sui Dynasty,[88] the government changed and expanded in its borders as the many separate bureaucracies unified under one banner.[89] This evolved into the Tang Dynasty when Li Yuan took control of China in 626.[90] By now, the Chinese borders had expanded from eastern China, up north into the Tang Empire.[91] The Tang Empire fell apart in 907 and split into ten regional kingdoms and five dynasties with vague borders.[92] Fifty-three years after the separation of the Tang Empire, China entered the Song Dynasty under the rule of Chao K'uang, although the borders of this country expanded, they were never as large as those of the Tang dynasty and were constantly being redefined due to attacks from the neighboring Tartar (Mongol) people known as the Khitan tribes.[93]

The Mongol Empire emerged from the unification of several nomadic tribes in the Mongol homeland under the leadership of Genghis Khan (c. 1162–1227), whom a council proclaimed as the ruler of all Mongols in 1206. The empire grew rapidly under his rule and that of his descendants, who sent out invading armies in every direction.[94][95] The vast transcontinental empire connected the East with the West, the Pacific to the Mediterranean, in an enforced Pax Mongolica, allowing the dissemination and exchange of trade, technologies, commodities and ideologies across Eurasia.[96][97]

The empire began to split due to wars over succession, as the grandchildren of Genghis Khan disputed whether the royal line should follow from his son and initial heir Ögedei or from one of his other sons, such as Tolui, Chagatai, or Jochi. The Toluids prevailed after a bloody purge of Ögedeid and Chagataid factions, but disputes continued among the descendants of Tolui. After Möngke Khan died (1259), rival kurultai councils simultaneously elected different successors, the brothers Ariq Böke and Kublai Khan, who fought each other in the Toluid Civil War (1260–1264) and also dealt with challenges from the descendants of other sons of Genghis.[98][99] Kublai successfully took power, but civil war ensued as he sought unsuccessfully to regain control of the Chagatayid and Ögedeid families. By the time of Kublai's death in 1294 the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives: the Golden Horde khanate in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, the Ilkhanate in the southwest, and the Yuan dynasty in the east, based in modern-day Beijing.[100]

In 1304 the three western khanates briefly accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Yuan dynasty,[101][102] but in 1368 the Han Chinese Ming dynasty took over the Mongol capital. The Genghisid rulers of the Yuan retreated to the Mongolian homeland and continued to rule there as the Northern Yuan dynasty. The Ilkhanate disintegrated in the period 1335–1353. The Golden Horde had broken into competing khanates by the end of the 15th century and was defeated and thrown out of Russia in 1480 by the Grand Duchy of Moscow while the Chagatai Khanate lasted in one form or another until 1687.

Middle East and Europe

The Byzantine–Sasanian Wars of 572–591 and 602–628 produced the cumulative effects of a century of almost continuous conflict, leaving both empires crippled. When Kavadh II died only months after coming to the throne, Persia was plunged into several years of dynastic turmoil and civil war. The Sasanians were further weakened by economic decline, heavy taxation from Khosrau II's campaigns, religious unrest, and the increasing power of the provincial landholders.[103] The Byzantine Empire was also severely affected, with its financial reserves exhausted by the war and the Balkans now largely in the hands of the Slavs.[104] Additionally, Anatolia was devastated by repeated Persian invasions; the Empire's hold on its recently regained territories in the Caucasus, Syria, Mesopotamia, Palestine and Egypt was loosened by many years of Persian occupation.[105] Neither empire was given any chance to recover, and according to George Liska, the "unnecessarily prolonged Byzantine–Persian conflict opened the way for Islam".[106]

The Quraysh ruled the cities of Mecca and Medina, and expelled their member Muhammad from the former to the latter in 622, from where he began spreading his new religion, Islam.[107] In 631 Muhammad marched with 10,000 to Mecca and conquered it before dying the next year.[108] His successors united most of Arabia in the Ridda wars (632-633) and then started the Muslim conquests of the Levant (634-641), Egypt (639-642) and Persia (633-651), the latter ending the Sasanian empire.[109] In less than a decade after his death, the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate extended its reach from Atlas Mountains in the west to the Hindu Kush in the east.[110] However, the First Fitna led to its replacement by the Umayyad Caliphate in 661, moving the centre of power to Damascus.[111] At its height, the Umayaads ruled a third of the world's population.[112] In 750, the Abbasid Caliphate replaced the Umayyads in the Abbasid Revolution.[113] In 762, they moved the capital to Baghdad.[114] The Emirate of Córdoba remained under Umayaad rule, while in 788 the Idrisid dynasty broke away in Morocco.[115] The Fatimid Caliphate started taking over North Africa from 909 onwards, and the Buyid dynasty dynasty broke away in Persia and later Mesopotamia starting in the 930's.[116]

In 711, the Umayyad conquest of Hispania began, and in 717 they crossed the Pyrenees into the European Plain.[117] They were met by the Merovingian dynasty, which had been established by Clovis I (481-511), which was in decline, leading Charles Martel to seize power and defeat the invasion force at the Battle of Tours in 732.[117] His son Pepin the Short established the Carolingian dynasty in 751.[117] Charlemagne (768-814) turned it into the Carolingian Empire, being crowned Emperor of the Romans in 800 by the Pope, with this forming the basis for the later Holy Roman Empire.[118] Meanwhile, in Eastern Europe, Krum (795-814) expanded the Bulgarian Empire.[119] The Treaty of Verdun divided Carolingian Empire into West, Middle and East Francia.[120]

In 1095, Pope Urban II proclaimed the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont. He encouraged military support for Byzantine Emperor Alexios I against the Seljuk Turks and an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Across all social strata in western Europe there was an enthusiastic popular response. Volunteers took a public vow to join the crusade. Historians now debate the combination of their motivations, which included the prospect of mass ascension into Heaven at Jerusalem, satisfying feudal obligations, opportunities for renown, and economic and political advantage. Initial successes established four Crusader states in the Near East: the County of Edessa; the Principality of Antioch; the Kingdom of Jerusalem; and the County of Tripoli. The crusader presence remained in the region in some form until the city of Acre fell in 1291, leading to the rapid loss of all remaining territory in the Levant. After this, there were no further crusades to recover the Holy Land.

India

Indian politics revolved around the struggle between the Buddhist Pala Empire, the Hindu Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty, the Jainist Rashtrakuta dynasty, as well as the Islamic caliphate.[121] The Pala Empire had risen around 750 in Bengal under Gopala I, while the Rashtrakutas had emreged around the same time in the Deccan Plateau and the southern coast under Dantidurga.[122] The Pratiharas first united the Indo-Gangetic Plain under Nagabhata I (c. 730-760), who has defeated an Islamic invasion of northern India.[122] The struggle between the four lasted for almost 200 years.[123] By the ninth century, the Ghaznavids, a breakaway from the caliphate, arose after taking advantage of the others' internal weaknesses.[124]

Early modern era

In the 15th and 16th centuries three major Muslim empires formed: the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, the Balkans and Northern Africa; the Safavid Empire in Greater Iran; and the Mughul Empire in South Asia. These imperial powers were made possible by the discovery and exploitation of gunpowder and more efficient administration. By the end of the 19th century, all three had declined, and by the early 20th century, with the Ottomans' defeat in World War I, the last Muslim empire collapsed.

In 1700, Charles II of Spain died, naming Phillip of Anjou, Louis XIV's grandson, his heir. Charles' decision was not well met by the British, who believed that Louis would use the opportunity to ally France and Spain and attempt to take over Europe. Britain formed the Grand Alliance with Holland, Austria and a majority of the German states and declared war against Spain in 1702. The War of the Spanish Succession lasted 11 years, and ended when the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1714.[128]

Less than 50 years later, in 1740, war broke out again, sparked by the invasion of Silesia, part of Austria, by King Frederick II of Prussia. Britain, the Netherlands and Hungary supported Maria Theresa. Over the next eight years, these and other states participated in the War of the Austrian Succession, until a treaty was signed, allowing Prussia to keep Silesia.[129][130] The Seven Years' War began when Theresa dissolved her alliance with Britain and allied with France and Russia. In 1763, Britain won the war, claiming Canada and land east of the Mississippi. Prussia also kept Silesia.[131]

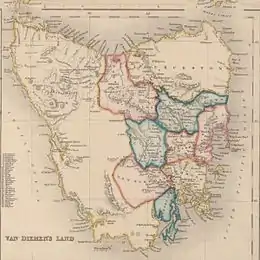

Interest in the geography of the Southern Hemisphere began to increase in the 18th century.[132] In 1642, Dutch navigator Abel Tasman was commissioned to explore the Southern Hemisphere; during his voyages, Tasman discovered the island of Van Diemen's Land, which was later named Tasmania, the Australian coast, and New Zealand in 1644.[133] Captain James Cook was commissioned in 1768 to observe a solar eclipse in Tahiti and sailed into Stingray Harbor on Australia's east coast in 1770, claiming the land for the British Crown.[134] Settlements in Australia began in 1788 when Britain began to utilize the country for the deportation of convicts,[135] with the first free settles arriving in 1793.[136] Likewise New Zealand became a home for hunters seeking whales and seals in the 1790s with later non-commercial settlements by the Scottish in the 1820s and 30s.[137]

In Northern America, revolution was beginning when in 1770, British troops opened fire on a mob pelting them with stones, an event later known as the Boston Massacre.[138] British authorities were unable to determine if this event was a local one, or signs of something bigger[139] until, in 1775, Rebel forces confirmed their intentions by attacking British troops on Bunker Hill.[140] Shortly after, Massachusetts Second Continental Congress representative John Adams and his cousin Samuel Adams were part of a group calling for an American Declaration of Independence. The Congress ended without committing to a Declaration, but prepared for conflict by naming George Washington as the Continental Army Commander.[139] War broke out and lasted until 1783, when Britain signed the Treaty of Paris and recognized America's independence.[141] In 1788, the states ratified the United States Constitution, going from a confederation to a union[139] and in 1789, elected George Washington as the first President of the United States.[142]

By the late 1780s, France was falling into debt, with higher taxes introduced and famines ensuring.[143] As a measure of last resort, King Louis XVI called together the Estates-General in 1788 and reluctantly agreed to turn the Third Estate (which made up all of the non-noble and non-clergy French) into a National Assembly.[144] This assembly grew very popular in the public eye and on July 14, 1789, following evidence that the King planned to disband the Assembly,[143] an angry mob stormed the Bastille, taking gunpowder and lead shot.[144] Stories of the success of this raid spread all over the country and sparked multiple uprisings in which the lower-classes robbed granaries and manor houses.[143] In August of the same year, members of the National Assembly wrote the revolutionary document Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen which proclaimed freedom of speech, press and religion.[143] By 1792, other European states were attempting to quell the revolution. In the same year Austrian and German armies attempted to march on Paris, but the French repelled them. Building on fears of European invasion, a radical group known as the Jacobins abolished the monarchy and executed King Louis for treason in 1793. In response to this radical uprising, Britain, Spain and the Netherlands join in the fight with the Jacobins until the Reign of Terror was brought to an end in 1794 with the execution of a Jacobin leader, Maximilien Robespierre. A new constitution was adopted in 1795 with some calm returning, although the country was still at war. In 1799, a group of politicians led by Napoleon Bonaparte unseated leaders of the Directory.[144]

References

- Fukuyama, Francis. (2012). The origins of political order : from prehuman times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-374-53322-9. OCLC 1082411117.

- Fukuyama, Francis. (2012). The origins of political order : from prehuman times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-374-53322-9. OCLC 1082411117.

- Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, p. 26, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, pp. 24–25, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, pp. 33–34, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Daniel, Glyn (2003) [1968]. The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins. New York: Phoenix Press. xiii. ISBN 1-84212-500-1.

- Daniel, Glyn (2003) [1968]. The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins. New York: Phoenix Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 1-84212-500-1.

- Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, pp. 34–35, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Holslag, Jonathan, author., A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, pp. 39–40, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. pp. 244–245. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. p. 56. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- Holslag, Jonathan, A political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace, McMillan, Roy, 1963-, [Place of publication not identified], p. 46, ISBN 978-0-241-38466-4, OCLC 1080190517

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan, author. (3 October 2019). Political history of the world : three thousand years of war and peace. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-241-39556-1. OCLC 1139013058.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin Books, Limited. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-241-35204-5.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-517665-0. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 118–21. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. pp. ix. ISBN 0-19-517665-0. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Herrmann, Albert (1970). Historical and Commercial Atlas of China. Ch'eng-wen Publishing House. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1995). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-8047-2353-2. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 134–5. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- Diamond. Guns, Germs, and Steel. p. 367.

- The Mongols and Russia, by George Vernadsky

- Gregory G.Guzman "Were the barbarians a negative or positive factor in ancient and medieval history?", The Historian 50 (1988), 568–70.

- Allsen. Culture and Conquest. p. 211.

- "The Islamic World to 1600: The Golden Horde". University of Calgary. 1998. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- Michael Biran. Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State in Central Asia. The Curzon Press, 1997, ISBN 0-7007-0631-3

- The Cambridge History of China: Alien Regimes and Border States. p. 413.

- Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 127.

- Allsen. Culture and Conquest. pp. xiii, 235.

- Howard-Johnston (2006), 9: "[Heraclius'] victories in the field over the following years and its political repercussions ... saved the main bastion of Christianity in the Near East and gravely weakened its old Zoroastrian rival."

- Haldon (1997), 43–45, 66, 71, 114–15

- Ambivalence toward Byzantine rule on the part of miaphysites may have lessened local resistance to the Arab expansion (Haldon [1997], 49–50).

- Liska (1998), 170

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Holslag, Jonathan (2018-10-25). A Political History of the World: Three Thousand Years of War and Peace. Penguin UK. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-241-35205-2.

- Tsouras, Peter (2005). Montezuma: Warlord of the Aztecs. Brassey's. pp. xv. ISBN 1-57488-822-6.

- Berdan, Frances F.; Richard E. Blanton; Elizabeth H. Boone; Mary G. Hodge; Michael E. Smith; Emily Umberger (1996). Aztec Imperial Strategies. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0-88402-211-0.

- Barlow, R.H. (1949). Extent of the Empire of the Culhua Mexica. Berkeley and Los Angeles Univ. of California.

- Frey, Marsha; Linda Frey (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-27884-9. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- Dupuy, Richard Ernes; Trevor Nevitt Dupuy (1970). The Encyclopedia of Military History: From 3500 B.C. to the Present. Harper & Row. p. 630. ISBN 9780060111397. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- Rosner, Lisa; John Theibault (2000). A Short History of Europe, 1600-1815: Search for a Reasonable World (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 292. ISBN 0-7656-0328-4. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- Marston, Daniel (2001). The Seven Years' War (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-191-5. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. p. 214. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- Porter, Malcolm; Keith Lye (2007). Australia and the Pacific (illustrated and revised 2007 ed.). Cherrytree Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-84234-460-6. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- Kitson, Arthur (2004). The Life of Captain James Cook. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 84–5. ISBN 1-4191-6947-5. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- King, Jonathan (1984). The First Settlement: The Convict Village that Founded Australia 1788-90. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-38080-0.

- Currer-Briggs, Noel (1982). Worldwide Family History (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 0-7100-0934-8.

- Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. p. 216. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- Lancaster, Bruce; John Harold Plumb; Richard M. Ketchum (2001). illustrated (ed.). The American Revolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 74. ISBN 0-618-12739-9. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 218–21. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- Lancaster, Bruce; John Harold Plumb; Richard M. Ketchum (2001). illustrated (ed.). The American Revolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 96–9. ISBN 0-618-12739-9. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Jedson, Lee (2006). The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Primary Source Examination of the Treaty That Recognized American Independence (illustrated ed.). The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 37. ISBN 1-4042-0441-5. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- Bloom, Sol; Lars Johnson (2001). The Story of the Constitution (2nd illustrated ed.). Christian Liberty Press. p. 84. ISBN 1-930367-56-2. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 222–25. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- S. Viault, Birdsall (1990). "The French Revolution". Schaum's Outline of Modern European History (revised ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 180–91. ISBN 0-07-067453-1. Retrieved 2008-01-31.