Isra and Mi'raj

The Israʾ and Miʿraj (Arabic: الإسراء والمعراج, al-’Isrā’ wal-Miʿrāj) are the two parts of a Night Journey that, according to Islam, the Islamic prophet Muhammad took during a single night around the year 621. Within Islam it signifies both a physical and spiritual journey.[1] The Quran surah al-Isra contains an outline account,[2] while greater detail is found in the hadith collections of the reports, teachings, deeds and sayings of Muhammad. In the accounts of the Israʾ, Muhammad is said to have traveled on the back of a winged baby-horse-like white beast, called Buraq, (Arabic: الْبُرَاق al-Burāq or /ælˈbʊrɑːk/ "lightning" or more generally "bright") to "the farthest mosque". By tradition this mosque, which came to represent the physical world, was identified as the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. At Masjid-e-Aqsa, Muhammad is said to have led the other prophets in prayer. His subsequent ascent into the heavens came to be known as the Miʿraj. Muhammad's journey and ascent is marked as one of the most celebrated dates in the Islamic calendar.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

|

|

Islamic sources

The events of Isra and Miʿraj mentioned briefly in the Quran are further enlarged and interpreted within the supplement to the Quran, the literary corpus known as hadith, which contain the reported sayings of Muhammad. Two of the best hadith sources are by Anas ibn Malik and Ibn ʿAbbas. Both were young boys at the time of Muhammad's journey of Mi'raj.[4]

The Quran

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Clothing |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

Within the Quran, chapter (surah) 17 al-Isra, contains a brief description of Isra in the first verse. Some scholars, including Sufi scholar Abu 'Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami,[5] say a verse in surah an-Najm also holds information on the Isra and Miʿraj.

Glory to Him who made His servant travel by night from the sacred place of worship to the furthest place of worship, whose surroundings We have blessed, to show him some of Our signs. He alone is the All Hearing, the All Seeing.[Quran 17:1 (Translated by Abdel Haleem)]

Remember when We said to you that your Lord encompasses mankind in His knowledge. Nor did We make the vision We showed you except as a test to people, as also the accursed tree in the Quran.[Quran 17:60 (Translated by Tarif Khalidi)]

A second time he saw him (an angel),

By the lote-tree which none may pass

near the Garden of Restfulness

when the tree was covered in nameless (splendour).

His sight never wavered, nor was it too bold.

and he saw some of the greatest signs of his Lord.[Quran 53:13–18 (Translated by Abdel Haleem)]

Ahadith

From various hadiths we learn much greater detail. The Israʾ is the part of the journey of Muhammad from Mecca to Jerusalem. It began when Muhammad was in the Great Mosque, and the Archangel Jibrīl (or Jibrāʾīl, Gabriel) came to him, and brought Buraq, the traditional heavenly mount of the prophets. Buraq carried Muhammad to al-Aqsa Mosque, the "Farthest Mosque", in Jerusalem. Muhammad alighted, tethered Buraq to the Temple Mount and performed prayer, where on God's command he was tested by Gabriel.[6][7] It was told by Anas ibn Malik that Muhammad said: "Jibra'il brought me a vessel of wine, a vessel of water and a vessel of milk, and I chose the milk. Jibra'il said: 'You have chosen the Fitrah (natural instinct).'" In the second part of the journey, the Miʿraj (an Arabic word that literally means "ladder"),[8] Jibra'il took him to the heavens, where he toured the seven stages of heaven, and spoke with the earlier prophets such as Abraham (ʾIbrāhīm), Moses (Musa), John the Baptist (Yaḥyā ibn Zakarīyā), and Jesus (Isa).[9] Muhammad was then taken to Sidrat al-Muntaha – a holy tree in the seventh heaven that Gabriel was not allowed to pass. According to Islamic tradition, God instructed Muhammad that Muslims must pray fifty times per day; however, Moses told Muhammad that it was very difficult for the people and urged Muhammad to ask for a reduction, until finally it was reduced to five times per day.[3][10][11][12][13]

The Mi‘raj

There are different accounts of what occurred during the Miʿraj, but most narratives have the same elements: Muhammad ascends into heaven with the angel Gabriel and meets a different prophet at each of the seven levels of heaven; first Adam, then John the Baptist and Jesus, then Joseph, then Idris, then Aaron, then Moses, and lastly Abraham. After Muhammad meets with Abraham, he continues on to meet Allah without Gabriel. Allah tells Muhammad that his people must pray 50 times a day, but as Muhammad descends back to Earth, he meets Moses who tells Muhammad to go back to God and ask for fewer prayers because 50 is too many. Muhammad goes between Moses and God nine times, until the prayers are reduced to the five daily prayers, which God will reward tenfold.[14] To that again, Moses tells Muhammad to ask for even fewer but Muhammad feels ashamed and says that he is thankful for the five.[15]

Al-Tabari is a classic and authentic source for Islamic research. His description of the Miʿraj is just as simplified as the description given above, which is where other narratives and hadiths of the Miʿraj stem from, as well as word of mouth. While this is the simplest description of the Miʿraj, others include more details about the prophets that Muhammad meets. In accounts written by Muslim, Bukhari, Ibn Ishaq, Ahmad b. Hanbal and others, physical descriptions of the prophets are given. Adam is described first as being Muhammad's father, which establishes a link between them as first and last prophets.[16] Physical descriptions of Adam show him as tall and handsome with long hair. Idris, who is not mentioned as much as the other prophets Muhammad meets, is described as someone who was raised to a higher status by God. Joseph, is described as the most beautiful man who is like the moon. His presence in the Miʿraj is to show his popularity and how it relates to Muhammad's. Aaron is described as Muhammad's brother who is older and one of the most beautiful men that Muhammad had met. Again, the love for Aaron by his people relates to Muhammad and his people. Abraham is described with likeness to Muhammad in ways that illustrate him to be Muhammad's father. Jesus is usually linked to John the Baptist, who is not mentioned much. The physical descriptions of Jesus vary, but he is said to be tall with long hair and white skin. Moses is different than the other prophets that Muhammad meets in that Moses stands as a point of difference rather than similarities.[16]

Some narratives also record events that preceded the heavenly ascent. Some scholars believe that the opening of Muhammad's chest was a cleansing ritual that purified Muhammad before he ascended into heaven. Muhammad's chest was opened up and water of Zamzam was poured on his heart giving him wisdom, belief, and other necessary characteristics to help him in his ascent. This purification is also seen in the trial of the drinks. It is debated when it took place—before or after the ascent—but either way it plays an important role in determining Muhammad's spiritual righteousness.[16]

Ibn ‘Abbas' Primitive Version

Ibn ʿAbbas' Primitive Version narrates all that Muhammad encounters throughout his journey through heaven. This includes seeing other angels, and seas of light, darkness, and fire. With Gabriel as his companion, Muhammad meets four key angels as he travels through the heavens. These angels are the Rooster angel (whose call influences all earthly roosters), Half-Fire Half-Snow angel (who provides an example of God's power to bring fire and ice in harmony), the Angel of Death (who describes the process of death and the sorting of souls), and the Guardian of Hellfire (who shows Muhammad what hell looks like). These four angels are met in the beginning of Ibn ʿAbbas' narrative. They are mentioned in other accounts of Muhammad's ascension, but they are not talked about with as much detail as Ibn ʿAbbas provides. As the narrative continues, Ibn Abbas focuses mostly on the angels that Muhammad meets rather than the prophets. There are rows of angels that Muhammad encounters throughout heaven, and he even meets certain deeply devoted angels called cherubim. These angels instill fear in Muhammad, but he later sees them as God's creation, and therefore not harmful. Other important details that Ibn ‘Abbas adds to the narrative are the Heavenly Host Debate, the Final Verses of the Cow Chapter, and the Favor of the Prophets.[17] These important topics help to outline the greater detail that Ibn ‘Abbas uses in his Primitive Version.

In an attempt to reestablish Ibn ‘Abbas as authentic, it seems as though a translator added the descent of Muhammad and the meeting with the prophets. The narrative only briefly states the encounters with the prophets, and does so in a way that is in chronological order rather than the normal order usually seen in ascension narratives. Ibn ʿAbbas may have left out the meeting of the prophets and the encounter with Moses that led to the reduction of daily prayers because those events were already written elsewhere. Whether he included that in his original narrative or if it was added by a later translator is unknown, but often a point of contention when discussing Ibn ‘Abbas's Primitive Version.[17]

Sufi Interpretations

The belief that Muhammad made the heavenly journey bodily was used to prove the unique status of Muhammad.[18] One theory among Sufis was that Muhammad’s body could reach God to a proximity that even the greatest saints could only reach in spirit.[18] They debated whether the Prophet had really seen the Lord, and if he did, whether he did so with his eyes or with his heart.[18] Nevertheless, the Prophet’s superiority is again demonstrated in that even in the extreme proximity of the Lord, “his eye neither swerved nor was turned away,” whereas Moses had fainted when the Lord appeared to him in a burning bush.[18] Various thinkers used this point to prove the superiority of the Prophet.[18] The Subtleties of the Ascension by Abu ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami includes repeated quotations from other mystics that also affirm the superiority of the Prophet.[19] Many Sufis interpreted the Miʿraj to ask questions about the meaning of certain events within the Miʿraj, and drew conclusions based on their interpretations, especially to substantiate ideas of the superiority of Muhammad over other prophets.[18]

Muhammad Iqbal, an self-proclaimed intellectual descendant of Rumi and the poet-scholar who personified poetic Sufism in South Asia, used the event of the Miʿraj to conceptualize an essential difference between a prophet and a Sufi.[20] He recounts that Muhammad, during his Miʿraj journey, visited the heavens and then eventually returned to the temporal world.[20] Iqbal then quotes another South Asian Muslim saint by the name of ‘Abdul Quddus Gangohi who asserted that if he (Gangohi) had had that experience, he would never have returned to this world.[20] Iqbal uses Gangohi's spiritual aspiration to argue that while a saint or a Sufi would not wish to renounce the spiritual experience for something this-worldly, a prophet is a prophet precisely because he returns with a force so powerful that he changes world history by imbuing it with a creative and fresh thrust.[20]

Modern Muslim observance

The Lailat al-Miʿraj (Arabic: لیلة المعراج, Lailatu 'l-Miʿrāj), also known as Shab-e-Mi'raj (Bengali: শবে মেরাজ, romanized: Šobe Meraj, Persian: شب معراج, Šab-e Mi'râj) in Iran, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, and Miraç Kandili in Turkish, is the Muslim holiday celebrating the Isra and Miʿraj. Some Muslims celebrate this event by offering optional prayers during this night, and in some Muslim countries, by illuminating cities with electric lights and candles. The celebrations around this day tend to focus on every Muslim who wants to celebrate it. Worshippers gather into mosques and perform prayer and supplication. Some people may pass their knowledge on to others by telling them the story on how Muhammad's heart was purified by the archangel Gabriel, who filled him with knowledge and faith in preparation to enter the seven levels of heaven. After salah, food and treats are served.[3][21][22]

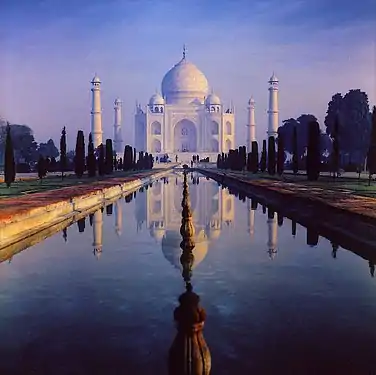

Al-Aqsa Mosque marks the place from which Muhammad is believed to have ascended to heaven. The exact date of the Journey is not clear, but is celebrated as though it took place before the Hegira and after Muhammad's visit to the people of Ta'if. It is considered by some to have happened just over a year before the Hijrah, on the 27th of Rajab; but this date is not always recognized. This date would correspond to the Julian date of 26 February 621, or, if from the previous year, 8 March 620. In Twelver Iran for example, Rajab 27 is the day of Muhammad's first calling or Mab'as. The al-Aqsa Mosque and surrounding area, marks the place from which Muhammad is believed to have ascended to heaven, is the third-holiest place on earth for Muslims.[23][24]

Many sects and offshoots belonging to Islamic mysticism interpret Muhammad's night ascent – the Isra and Miʿraj – to be an out-of-body experience through nonphysical environments,[25][26] unlike the Sunni Muslims or mainstream Islam. The mystics claim Muhammad was transported to Jerusalem and onward to the Seven Heavens, even though "the apostle's body remained where it was."[27] Esoteric interpretations of the Quran emphasise the spiritual significance of Miʿraj, seeing it as a symbol of the soul's journey and the potential of humans to rise above the comforts of material life through prayer, piety and discipline.[8]

Historical issues related to this event

The issue with these verses and story lies in that the Temple was built by Solomon and later destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar's Babylonian army in 586 BC. Furthermore, Roman general Titus and his Roman soldiers leveled the Second Temple in AD 70, more than five centuries before this alleged night journey to Jerusalem took place. However, after the initially successful Jewish revolt against Heraclius, the Jewish population resettled in Jerusalem for a short period of time from 614 to 630 and immediately started to restore the temple on the Temple Mount and build synagogues in Jerusalem.[28][29] Furthermore, after the Jewish population was expelled a second time from Jerusalem and shortly before Heraclius retook Jerusalem (630), a small Synagogue was already in place on the Temple Mount. This synagogue was demolished after Heraclius retook Jerusalem.[30]

Some claim that the place that was eventually called Masjid al-Aqsa was not constructed until AD 690-691 when ʿAbd al-Malik bin Marwan built the Mosque known as the Farthest Mosque (Masjid-ul-Aqsa) with the structure known as Dome of the Rock. But this is inaccurate. The general consensus between Muslim scholars is that the Isra and Mi’raj were specific to a literal building, called Masjid Al-Aqsa, and that Muhammad did indeed go to a physical location at which a masjid structure (building) was already built.

It is not known where the concept that the mi'raj (journey) was not specific to a single structure in Jerusalem came from; in one instance, authors Watt/Welch claim that "the word masjid, which is used in the surah above literally translates as a 'place of prostration/worship' and thus indicates any place of worship, not necessarily a building."[31]

However, Muhammad himself described this extraordinary experience in the following words:

"Then Gabriel brought a horse (Burraq) to me, which resembled lightning in swiftness and lustre, was of clear white colour, medium in size, smaller than a mule and taller than a (donkey), quick in movement that it put its feet on the farthest limit of the sight. He made me ride it and carried me to Jerusalem. He tethered the Burraq to the ring of that Temple to which all the Prophets in Jerusalem used to tether their beasts..." [32]

Similarities to other Abrahamic traditions

Traditions of living persons ascending to heaven are also found in early Jewish and Christian literature.[33] For example, the Book of Enoch, a late second temple Jewish apocryphal work, describes a tour of heaven given by an angel to the patriarch Enoch, the great-grandfather of Noah. According to Brooke Vuckovic, early Muslims may have had precisely this ascent in mind when interpreting Muhammad's night journey. [34] In the Testament of Abraham, from the first century CE, Abraham is shown the final judgement of the righteous and unrighteous in heaven.

Similarities in the Book of Arda Viraf

Critic of Islam, Ibn Warraq, has long contended that the story of Israʾ and Miʿraj was likely taken from the Book of Arda Viraf, given the shared overarching narrative of an ascension into heaven and other striking similarities.[35] However, according to Mary Boyce, a philologist and an authority on Zoroastrianism, the Arda Viraf's simple, direct prose and the fact that there are indications it underwent redactions well after the Arab conquest, makes it highly likely that it is a literary product of the 9th and 10th century.[36] Moreover, the ubiquitous presence of "Persianisms" in the text is further evidence that the final recension likely took form extremely late, with Orientalist Philippe Gignoux dating it to around the 10th or 11th century.[37]

See also

- Al-Hijaz (Arabic: الـحِـجـاز)

- Al-Mashriq (Arabic: الـمَـشـرق, The Levant)

- Ash-Sham (Arabic: الـشَّـام, "The Syria" (region, not to be confused with the country of Syria))

- Ash-Sharq Al-Awsat (Arabic: الـشَّـرق الأَوسـط, The Middle East)

- Miraj Nameh

- Islamic view of miracles

- Transfiguration of Jesus

References

- Martin, Richard C.; Arjomand, Saïd Amir; Hermansen, Marcia; Tayob, Abdulkader; Davis, Rochelle; Voll, John Obert, eds. (2 December 2003). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Macmillan Reference USA. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-02-865603-8.

- Quran 17:1 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- Bradlow, Khadija (18 August 2007). "A night journey through Jerusalem". Times Online. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Colby, Frederick S. (2008). Narrating Muhammad's Night Journey: Teaching the Development of the Ibn 'Abbas Ascension Discourse. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7518-8.

- Colby, Frederick S. (2002). "The Subtleties of the Ascension: al-Sulamī on the Mi'rāj of the Prophet Muhammad". Studia Islamica (94): 167–183. doi:10.2307/1596216. ISSN 0585-5292. JSTOR 1596216.

- Momina. "isra wal miraj". chourangi. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- "Meraj Article". duas.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Mi'raj — The night journey

- "Sahih Al Bukhari | Hadith 4.648 | Quran & Hadith Translation Online | Alim". www.alim.org. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- IslamAwareness.net – Isra and Mi'raj, The Details Archived 24 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- About.com – The Meaning of Isra' and Miʿraj in Islam Archived 6 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Vuckovic, Brooke Olson (30 December 2004). Heavenly Journeys, Earthly Concerns: The Legacy of the Mi'raj in the Formation of Islam (Religion in History, Society and Culture). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96785-3.

- Mahmoud, Omar (25 April 2008). "The Journey to Meet God Almighty by Muhammad—Al-Isra". Muhammad: an evolution of God. AuthorHouse. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4343-5586-7. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- al-Tabari (1989). The History of al-Tabari volume VI: Muhammad at Mecca. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-88706-706-9.

- https://sunnah.com/bukhari/97/142

- Vuckovic, Brooke Olsen (2005). Heavenly Journeys, Earthly Concerns: The Legacy of the Miʿraj in the Formation of Islam. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96785-6.

- Colby, Frederick S (2008). Narrating Muhammad's Night Journey: Tracing the Development of the Ibn 'Abbas Ascension Discourse. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7518-8.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1985). And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1639-4.

- Colby, Frederick (2002). "The Subtleties of the Ascension: al-Sulami on the Miraj of the Prophet Muhammad". Studia Islamica: 167–183. doi:10.2307/1596216. JSTOR 1596216.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1985). And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety. The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 247–248. ISBN 978-0-8078-1639-4.

- "BBC – Religions – Islam: Lailat al Miraj". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- "WRMEA – Islam in America". Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- Jonathan M. Bloom; Sheila Blair (2009). The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- Oleg Grabar (1 October 2006). The Dome of the Rock. Harvard University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-674-02313-0. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- Brent E. McNeely, "The Miraj of Prophet Muhammad in an Ascension Typology" Archived 30 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, p3

- Buhlman, William, "The Secret of the Soul", 2001, ISBN 978-0-06-251671-8, p111

- Brown, Dennis; Morris, Stephen (2003). "Religion and Human Experience". A Student's Guide to A2 Religious Studies: for the AQA Specification. Rhinegold Eeligious Studies Study Guide. London, UK: Rhinegold. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-904226-09-3. OCLC 257342107. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

The revelation of the Qur'an to Muhammad [includes] his Night Journey, an out-of-body experience where the prophet was miraculously taken to Jerusalem on the back of a mythical bird (buraq)....

- Ghada, Karmi (1997). Jerusalem Today: What Future for the Peace Process?. pp. 115–116.

- Kohen, Elli. "5". History of the Byzantine Jews: A Microcosmos in the Thousand Year Empire. p. 36.

- R. W. THOMSON (1999). The Armenian History Attributed to Sebeos. Liverpool University Press. pp. 208–212. ISBN 9780853235644.

- Watt/Welch (1980). Der Islam I. pp. 288–291.

- Siddiqui, Abdul Hameed. The Life of Muhammad. Islamic Book Trust: Kuala Lampur. 1999. p.113. ISBN 983-9154-11-7

- Bremmer, Jan N. "Descents to hell and ascents to heaven in apocalyptic literature." JJ Collins (Hg.), The Oxford Handbook of Apocalyptic Literature, Oxford (2014): 340-357.

- Vuckovic, Brooke Olson. Heavenly journeys, earthly concerns: the legacy of the mi'raj in the formation of Islam. Routledge, 2004, 46.

- Warraq, Ibn (1995). Why I Am Not a Muslim. Prometheus Books. pp. 45–47. ISBN 0-87975-9844.

- M. Boyce, “Middle Persian Literature”, Handbuch Der Orientalistik, 1968, Band VIII, Iranistik: Zweitter Abschnitt, E. J. Brill: Leiden/Köln, p. 48

- P. Gignoux, “Notes Sur La Redaction De L’Arday Viraz Namag: L’Emploi De Hamê Et De Bê”, Zeitschrift Der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 1969, SupplementaI, Teil 3, pp. 998-999.

Further reading

- Asad, Muhammad (1980). "Appendix IV: The Night Journey". The Message of the Qu'rán. Gibraltar, Spain: Dar al-Andalus Limited. ISBN 1904510000.

- Colby, Frederick, "Night Journey (Isra & Mi'raj), in Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (2 vols.), Edited by C. Fitzpatrick and A. Walker, Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2014, Vol II, pp. 420–425.

- Schimmel, Annemarie, "The Prophet's Night Journey and Ascension", in And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1985.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isra and Mi'raj. |

- Author Unknown, "Commemorating The Prophet's Rapture And Ascension To His Lord" in Sunnah.org (last accessed 24 September 2017)

- "Isra and Miraj: The Miraculous Night Journey in Daiyah (last accessed 24 September 2017)

- Israa and Miraj in Learn Deen (last accessed 24 September 2017)

- A. Bevan, Muhammad's Ascension to Heaven, in "Studien zu Semitischen Philologie und Religionsgeschichte Julius Wellhausen," (Topelman, 1914, pp. 53–54.)

- B. Schrieke, "Die Himmelsreise Muhammeds," Der Islam 6 (1915–16): 1–30

- Colby, Frederick. The Subtleties of the Ascension: Lata'if Al-Miraj: Early Mystical Sayings on Muhammad's Heavenly Journey. City: Fons Vitae, 2006.

- Hadith On Isra and Mi'raj from Sahih Muslim

.jpg.webp)