Moses in Islam

Mūsā ibn ʿImrān[1] (Arabic: موسی ابن عمران, Moses son of Amram) known as Moses in Judaeo-Christian theology, considered a prophet and messenger in Islam, is the most frequently mentioned individual in the Qur'an, his name being mentioned 135 times.[2] The Quran states that Musa was sent by Allah to the Pharaoh of Egypt and his establishments and the Israelites for guidance and warning. Musa is mentioned more in the Qur'an than any other individual, and his life is narrated and recounted more than that of any other prophet.[3] According to Islam, all Muslims must have faith in every prophet (nabi) and messenger (rasul) which includes Musa and his brother. The Qur'an states:

And mention in the Book, Moses. Indeed, he was chosen, and he was a messenger and a prophet. And We called him from the side of the mount at [his] right and brought him near, confiding [to him]. And We gave him out of Our mercy his brother Aaron as a prophet.

Prophet

|

|---|

1.png.webp) |

|

Part of a series on Islam Islamic prophets |

|---|

|

|

|

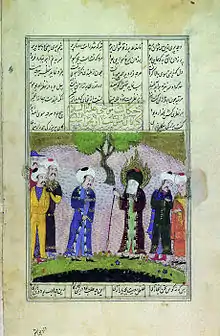

Musa is considered to be a prophetic predecessor to Muhammad. The tale of Musa is generally seen as a spiritual parallel to the life of Muhammad, and Muslims consider many aspects of their lives to be shared.[5][6][7] Islamic literature also describes a parallel between their believers and the incidents which occurred in their lifetimes. The exodus of the Israelites from Egypt is considered similar to the (migration) from Mecca made by the followers of Muhammad.[8]

Musa is also very important in Islam for having been given the revelation of the Torah. Moreover, according to Islamic tradition, Musa was one of the many prophets Muhammad met in the event of the Mi'raj, when he ascended through the seven heavens.[9] During the Mi'raj, Musa is said to have urged Muhammad to ask God to reduce the number of required daily prayers until only the five obligatory prayers remained. Musa is further revered in Islamic literature, which expands upon the incidents of his life and the miracles attributed to him in the Qur'an and hadith, such as his direct conversation with God.

Traditional narrative in Islam

Childhood

According to Islamic tradition, Musa was born into a family of Israelites living in Egypt. Of his family, Islamic tradition generally names his father 'Imram, corresponding to the Amram of the Hebrew Bible, traditional genealogies name Levi as his ancestor.[10] Islam states that Musa was born in a time when the ruling Pharaoh had enslaved the Israelites after the time of the prophet Joseph (Yusuf). Around the time of Musa's birth, Islamic literature states that the Pharaoh had a dream in which he saw fire coming from the city of Jerusalem, which burnt everything in his kingdom except in the land of the Israelites. (Other stories said that the Pharaoh dreamt of a little boy who caught the Pharaoh's crown and destroyed it.)[11] although there is no authentic islamic reference to whether the dreams actually occurred. When the Pharaoh was informed that one of the male children would grow up to overthrow him, he ordered the killing of all newborn Israelite males in order to prevent the prediction from occurring.[12] Islamic literature further states that the experts of economics in Pharaoh's court advised him that killing the male infants of the Israelites would result in loss of manpower.[13] Therefore, they suggested that the male infants should be killed in one year but spared the next.[13] Aaron was born in the year in which infants were spared, while Moses was born in the year in which infants were to be killed.[14]

On the Nile

According to Islamic tradition, Musa's mother suckled him secretly during this period. The Qur'an states that when they were in danger of being caught, God inspired her to put him in a basket and set him adrift on the Nile.[15] She instructed her daughter to follow the course of the ark and to report back to her. As her daughter followed the ark along the riverbank, Musa was discovered by the Pharaoh's wife, Asiya, who convinced the Pharaoh to adopt him.[16][17] The Qur'an states that when Asiya ordered wet nurses for Musa, Musa refused to be breastfed. Islamic tradition states that this was because God had forbidden Musa from being fed by any wet nurse in order to reunite him with his mother.[18] His sister worried that Moses had not been fed for some time, so she appeared to the Pharaoh and informed him that she knew someone who could feed him.[19] Islamic tradition states that after being questioned, she was ordered to bring the woman being discussed.[19] The sister brought their mother who fed Moses and thereafter she was appointed as the wet nurse of Moses.[20]

Test of prophecy

According to Isra'iliyat hadith, during his childhood when Musa was playing on the Pharaoh's lap, he grabbed the Pharaoh's beard and slapped him in the face. This action prompted the Pharaoh to consider Musa as the Israelite who would overthrow him, and the Pharaoh wanted to kill Musa. The Pharaoh's wife persuaded him not to kill him because he was an infant. Instead, he decided to test Musa.[21] Two plates were set before young Musa, one contained rubies and the other held glowing coals.[21] Musa reached out for the rubies, but the angel Gabriel directed his hand to the coals. Musa grabbed a glowing coal and put it in his mouth, burning his tongue.[22] After the incident Musa suffered from a speech defect but was spared by the Pharaoh.[23][24]

Escape to Midian

After having reached adulthood, the Qur'an states that when Musa was passing through a city, he came across Egyptian fighting with an Israelite. The Israelite man is believed to be "Sam'ana" known in the bible to be a Samaritan, who asked Musa for his assistance against the Egyptian. Musa attempted to intervene and became involved in the dispute.[25] In Islamic tradition, Musa struck the Egyptian in a state of anger which resulted in his death.[26] Musa then repented to God and the following day, he again came across the same Israelite fighting with another Egyptian. The Israelite again asked Musa for help, and as Musa approached the Israelite, he reminded Musa of his manslaughter and asked if Musa intended to kill him. Musa was reported and the Pharaoh ordered Musa to be killed. However, Musa fled to the desert after being alerted to his punishment.[12] According to Islamic tradition, after Musa arrived in Midian, he witnessed two female shepherds driving back their flocks from a well.[27] Musa approached them and inquired about their work as shepherds and their retreat from the well. Upon hearing their answers and the old age of their father, Musa watered their flocks for them.[27] The two shepherdesses returned to their home and informed their father of the incident. The Qur'an states that they invited Musa to a feast. At that feast, their father asked Musa to work for him for a period of eight or ten years, in return for marriage to one of his daughters.[25] Moses consented and worked for him during the period.[25]

Call to prophethood

According to the Qur'an, Musa departed for Egypt along with his family after completing the time period. The Qur'an states that during their travel, as they stopped near the Tur, Musa observed a large fire and instructed the family to wait until he returned with fire for them. When Musa reached the Valley of Tuwa, God called out to him from the right side of the valley from a tree, on what is revered as Al-Buq‘ah Al-Mubārakah ("The Blessed Ground") in the Qur'an.[28] Musa was commanded by God to remove his shoes and was informed of his selection as a prophet, his obligation of prayer and the Day of Judgment. Musa was then ordered to throw his rod which turned into a snake and later instructed to hold it.[29] The Qur'an then narrates Musa being ordered to insert his hand into his clothes and upon revealing it would shine a bright light.[30] God states that these are signs for the Pharaoh, and orders Musa to invite Pharaoh to the worship of one God.[30] Musa states his fear of Pharaoh and requests God to heal his speech impediment, and grant him his brother Aaron (Harun) as a helper. According to Islamic tradition, both of them stated their fear of Pharaoh but were assured by God that He would be observing them and commands them to inform the Pharaoh to free the Israelites. Therefore, they depart to preach to the Pharaoh.[27]

Arrival at Pharaoh's court

When Musa and Haroon arrived in the court of Pharaoh and proclaimed their prophethood to the Pharaoh, the Pharaoh began questioning Musa about the God he followed. The Qur'an narrates that Musa answered the Pharaoh by stating that he followed the God who gave everything its form and guided them.[31] The Pharaoh then inquires about the generations who passed before them and Musa answers that knowledge of the previous generations was with God.[32] The Qur'an also mentions the Pharaoh questioning Musa: “And what is the Lord of the worlds?”[33] Musa replies that God is the lord of the heavens, the earth and what is between them. The Pharaoh then reminds Musa of his childhood with them and the killing of the man he had done.[34] Musa admitted that he had committed the deed in ignorance, but insisted that he was now forgiven and guided by God. Pharaoh accused him of being mad and threatened to imprison him if he continued to proclaim that the Pharaoh was not the true god. Musa informed him that he had come with manifest signs from God.[35] In response, the Pharaoh demanded to see the signs. Musa threw his staff to the floor and it turned into a serpent.[36] He then drew out his hand and it shined a bright white light. The Pharaoh's counselors advised him that this was sorcery and on their advice he summoned the best sorcerers in the kingdom. Pharaoh challenged him to a battle between him and the Pharaoh's magicians, asking him to choose the day. Musa chose the day of a festival.

Confrontation with sorcerers

.jpg.webp)

When the sorcerers came to the Pharaoh, he promised them that they would be amongst the honored among his assembly if they won. On the day of the festival of Egypt, Moses granted the sorcerers the chance to perform first and warned them that God would expose their tricks. The Qur'an states that the sorcerers bewitched the eyes of the observers and caused them terror.[37] The summoned sorcerers threw their rods on the floor and they appeared to change into snakes by the effect of their magic. At first, Moses became concerned witnessing the tricks of the magicians, but was assured by God to not be worried. When Moses reacted likewise with his rod, the serpent devoured all the snakes.[38] The sorcerers realized that they had witnessed a miracle. They proclaimed belief in the message of Moses and fell onto their knees in prostration despite threats from the Pharaoh. Pharaoh was enraged by this and accused them of working under Moses. He warned them that if they insisted in believing in Moses, that he would cut their hands and feet on opposite sides, and crucify them on the trunks of palm trees for their firmness in their faith. The magicians, however, remained steadfast to their newfound faith and were killed by Pharaoh.[39]

Plagues of Egypt

After losing against Moses, the Pharaoh continued to plan against Moses and the Israelites, and ordered meetings of the ministers, princes and priests. According to the Qur'an, the Pharaoh is reported to have ordered his minister, Haman, to build a tower so that he "may look at the God of Moses".[40] Gradually, Pharaoh began to fear that Moses may convince the people that he was not the true god, and wanted to have Moses killed. After this threat, a man from the family of Pharaoh, who had years ago warned Moses, came forth and warned the people of the punishment of God for the wrongdoers and reward for the righteous. The Pharaoh defiantly refused to allow the Israelites to leave Egypt. The Qur'an states that God decreed punishments over him and his people. These punishments came in the form of floods that demolished their dwellings, swarms of locust that destroyed the crops,[41] pestilence of lice that made their life miserable,[42] toads that croaked and sprang everywhere, and the turning of all drinking water into blood. Each time the Pharaoh was subjected to humiliation, his defiance became greater. The Qur'an mentions that God instructed Moses to travel at night with the Israelites, and warned them that they would be pursued. The Pharaoh chased the Israelites with his army after realizing that they had left during the night.[43]

Splitting of the sea

Having escaped and then being pursued by the Egyptians, the Israelites stopped when they reached the seafront. The Israelites exclaimed to Moses that they would be overtaken by Pharaoh and his army. The Qur'an narrates God commanded Moses to strike the Red Sea with his staff, instructing them not to fear being overtaken or drowning. Upon striking the sea, it divided into two parts, that allowed the Israelites to pass through. The Pharaoh witnessed the sea splitting alongside his army, but as they also tried to pass through, the sea closed in on them.[44][45] As he was about to die, Pharaoh claimed belief in the God of Moses and the Israelites, but his belief was rejected by God.[46] The Qur'an states that the body of the Pharaoh was made a sign and warning for all future generations. As the Israelites continued their journey to the Promised Land, they came upon a people who were worshipping idols. The Israelites requested to have an idol to worship, but Moses refused and stated that the polytheists would be destroyed by God.[47] They were granted manna and quail as sustenance from God, but the Israelites asked Moses to pray to God for the earth to grow lentils, onions, herbs and cucumbers for their sustenance.[48] When they stopped in their travel to a promised land due to their lack of water, Moses was commanded by God to strike a stone, and upon its impact twelve springs came forth, each for a specific tribe of the Israelites.[49]

Revelation of the Torah

.jpg.webp)

After leaving the promised land, Moses led the Israelites to Mount Sinai (the Tur). Upon arrival, Moses left the people, instructing them that Aaron was to be their leader during his absence. Moses was commanded by God to fast for thirty days and to then proceed to the valley of Tuwa for guidance. God ordered Moses to fast again for ten days before returning. After completing his fasts, Moses returned to the spot where he had first received his miracles from God. He took off his shoes as before and went down into prostration. Moses prayed to God for guidance, and he begged God to reveal himself to him.[50] It is narrated in the Qur'an that God told him that it would not be possible for Moses to perceive God, but that He would reveal himself to the mountain stating: "By no means canst thou see Me (direct); But look upon the mount; if it abide in its place, then shalt thou see Me." When God revealed himself to the mountain, it instantaneously turned into ashes, and Moses lost consciousness. When he recovered, he went down in total submission and asked forgiveness of God.[51]

Moses was then given the Ten Commandments by God as Guidance and as Mercy. Meanwhile, in his absence, a man named Samiri had created a Golden Calf, proclaiming it to be the God of Moses.[52] The people began to worship it. Aaron attempted to guide them away from the Golden Calf, but the Israelites refused to do so until Moses had returned. Moses, having thus received the scriptures for his people, was informed by God that the Israelites had been tested in his absence and they had gone astray by worshiping the Golden Calf. Moses came down from the mountain and returned to his people.[53] The Qur'an states that Moses, in his anger, grabbed hold of Aaron by his beard and admonished him for doing nothing to stop them. But when Aaron told Moses of his fruitless attempt to stop them, Moses understood his helplessness and they both prayed to God for forgiveness. Moses then questioned Samiri for creating the Golden Calf. Samiri replied that it had occurred to him and he had done so.[54] Samiri was exiled and the Golden Calf was burned to ashes, and the ashes were thrown into the sea. The wrong-doers who had worshipped the Calf were ordered to be killed for their crime.[55]

Moses then chose seventy elites from among the Israelites and ordered them to pray for forgiveness. Shortly thereafter, the elders travelled alongside Moses to witness the speech between Moses and God. Despite witnessing the speech between them, they refused to believe until they saw God with their own eyes, so as punishment, a thunderbolt killed them. Moses prayed for their forgiveness, and they were resurrected and returned to camp and set up a tent dedicated to worshiping God as Aaron had taught them from the Torah. They resumed their journey towards the promised land.

The Israelites and the cow

Islamic exegesis narrates the incident of an old and pious man who lived among the Israelites and earned his living honestly. As he was dying, he placed his wife, his little son, and his only possession, a calf in God's care, instructing his wife to take the calf and leave it in a forest.[56] His wife did as she was told, and after a few years when the son had grown up, she informed him about the calf. The son traveled to the forest with a rope.[57] He prostrated and prayed to God to return the calf to him. As the son prayed, the now-grown cow stopped beside him. The son took the cow with him. The son was also pious and earned his living as a lumberjack.

One wealthy man among the Israelites died and left his wealth to his son. The relatives of the wealthy son secretly murdered the son in order to inherit his wealth. The other relatives of the son came to Moses and asked his help in tracing the killers. Moses instructed them to slaughter a cow and cut out its tongue, and then place it on the corpse, and that this would reveal the killers.[58] This confused the relatives who did not believe Moses, and did not understand why they were instructed to slaughter a cow when they were trying to find the killers. They accused Moses of joking, but Moses managed to convince them that he was serious.

Hoping to delay the process, the relatives asked the type and age of the cow they should slaughter, but Moses told them that it was neither old nor young but in-between the two ages.[59] Instead of searching for the cow described, they inquired about its colour, to which Moses replied that it was yellow.[60] They asked Moses for more details, and he informed them that it was unyoked, and did not plow the soil nor did it water the tilth. The relatives and Moses searched for the described cow, but the only cow that they found to fit the description belonged to the orphaned youth.[61] The youth refused to sell the cow without consulting his mother. All of them traveled together to the youth's home. The mother refused to sell the cow, despite the relatives constantly increasing the price. They urged the orphaned son to tell his mother to be more reasonable. However, the son refused to sell the cow without his mother's agreement, claiming that he would not sell it even if they offered to fill its skin with gold. At this the mother agreed to sell it for its skin filled with gold. The relatives and Moses consented, and the cow was slaughtered and the corpse was touched by the tongue.[62] The corpse rose back to life and revealed the identity of the killers.

Meeting with Khidr

According to a hadith, once when Moses delivered an impressive sermon, an Israelite inquired if there was anyone more knowledgeable than him.[63] When Moses denied any such person existed, he received a revelation from God, which admonished Moses for not attributing absolute knowledge to God and informed Moses that there was someone named Khidr who was more knowledgeable than him.[63] Upon inquiry, God informed Moses that Khidr would be found at the junction of two seas. God instructed Moses to take a live fish and at the location where it would escape, Khidr would be found.[63] Afterwards Moses departed and traveled alongside with a boy named Yusha (Yeshua bin Nun), until they stopped near a rock where Moses rested. While Moses was asleep, the fish escaped from the basket. When Moses woke up, they continued until they stopped for eating. At that moment, Joshua remembered that the fish had slipped from the basket at the rock. He informed Moses about the fish, and Moses remembered God's statement, so they retraced their steps back to the rock. There they saw Khidr. Moses approached Khidr and greeted him. Khidr instead asked Moses how people were greeted in their land. Moses introduced himself, and Khidr identified him as the prophet of the Israelites. According to the Qur'an, Moses asked Khidr "shall I closely follow you on condition that you teach me of what you have been taught".[64] Khidr warned that he would not be able to remain patient and consented on the condition that Moses would not question his actions.[63]

They walked on the seashore and passed by a ship. The crew of the ship recognized Khidr and offered them to come aboard their ship without any price. When they were on the boat, Khidr took an adze and pulled up a plank.[65] When Moses noticed what Khidr was doing, he was astonished and stopped him. Moses reminded Khidr that the crew had taken them aboard freely. Khidr admonished Moses for forgetting his promise of not asking. Moses stated that he had forgotten and asked to be forgiven. When they left the seashore, they passed by a boy playing with others. Khidr took a hold of the boy's head and killed him.[65] Moses was again astonished by this action and questioned Khidr regarding what he had done.[66] Khidr admonished Moses again for not keeping his promise, and Moses apologized and asked Khidr to leave him if he again questioned Khidr. Both of them traveled on until they came along some people of a village. They asked the villagers for food, but the inhabitants refused to entertain them as guests. They saw therein a wall which was about to collapse, and Khidr repaired the wall. Moses asked Khidr why he had repaired the wall when the inhabitants had refused to entertain them as guests and had not given them food. Moses stated that Khidr could have taken wages for his work.

Khidr informed Moses that they were now to part as Moses had broken his promise. Khidr then explained each of his actions. He informed Moses that he had broken the ship with the adze because a ruler who reigned in those parts took all functional ships by force, Khidr had created a defect in order to prevent their ship from being taken by force.[66] Khidr then explained that he had killed the child because he was disobedient to his parents and Khidr feared that the child would overburden them with his disobedience, and explained that God would replace him with a better one who was more obedient and had more affection. Khidr then explained that he had fixed the wall because it belonged to two hapless children whose father was pious. God wished to reward them for their piety. Khidr stated that there was a treasure hidden underneath the wall and by repairing the wall now, the wall would break in the future and when dealing with the broken wall, the orphans would find the treasure.[67]

Other incidents

The sayings of Muhammad (hadith), Islamic literature and Qur'anic exegesis also narrate some incidents of the life of Moses. Moses used to bathe apart from the other Israelites who all bathed together. This led the Bani Israel to say that Moses did so due to a scrotal hernia. One day when Moses was bathing in seclusion, he put his clothes on a stone which then fled with his clothes. Moses rushed after the stone and the Bani Israel saw him and said, 'By Allah, Moses has got no defect in his body." Moses then beat the stone with his clothes, and Abu Huraira stated, "By Allah! There are still six or seven marks present on the stone from that excessive beating." .[68] In a hadith, Muhammad states that the stone still had three to five marks due to Moses hitting it.[68]

Death

Haroon died shortly before Moses. It is reported in a Sunni hadith that when the angel of death, came to Moses, Moses slapped him in the eye. The angel returned to God and told him that Moses did not want to die.[69] God told the angel to return and tell Moses to put his hand on the back of an ox and for every hair that came under his hand he would be granted a year of life. When Moses asked God what would happen after the granted time, God informed him that he would die after the period. Moses, therefore, requested God for death at his current age near the Promised Land "at a distance of a stone's throw from it."[70]

Martyrdom

Moreover, by indicating that Moses wants to be separated from Aaron, his brother, many of the Israelites proclaim that Moses killed Aaron on the mountain to secure this so-called separation. However, according to the accounts of al-Tabari, Aaron died of natural causes: “When they [Moses and Aaron] fell asleep, death took Aaron.... When he was dead, the house was taken away, the tree disappeared, and the bed was raised to heaven”.[71] When Moses returned to the Children of Israel, his followers, from the mountain without Aaron, they were found saying that Moses killed Aaron because he had envied their love for him, for Aaron was more forbearing and more lenient with them. This notion would strongly indicate that Moses could have indeed killed Aaron to secure the separation in which he prayed to God for. To redeem his faith to his followers though, al-Tabari quotes Moses by saying “He was my brother. Do you think that I would kill him?”.[72] As stated in the Shorter Encyclopedia of Islam, it was recorded that Moses recited two rak’ahs to regain the faith of his followers. God answers Moses’ prayers by making the bed of Aaron descend from heaven to earth so that the Children of Israel could witness the truth that Aaron died of natural causes.[73]

The unexpected death of Aaron appears to make the argument that his death is merely an allusion to the mysterious and miraculous death of Moses. In the accounts of Moses’ death, al-Tabari reports, “[W]hile Moses was walking with his servant Joshua, a black wind suddenly approached. When Joshua saw it, he thought that the Hour—the hour of final judgement—was at hand. He clung to Moses…. But Moses withdrew himself gently from under his shirt, leaving it in Joshua’s hand”.[74] This mysterious death of Moses is also asserted in Deuteronomy 34:5, “And Moses the servant of the LORD died there in Moab.”[75] There is no explanation to why Moses may have died or why Moses may have been chosen to die: there is only this mysterious “disappearance.” According to Islamic tradition, Moses is buried at Maqam El-Nabi Musa, Jericho.

Although the death of Moses seems to be a topic of mysterious questioning, it is not the main focus of this information. However, according to Arabic translation of the word martyr, shahid—to see, to witness, to testify, to become a model and paradigm [76] – is the person who sees and witnesses, and is therefore the witness, as if the martyr himself sees the truth physically and thus stands firmly on what he sees and hears. To further this argument, in the footnotes of the Qur'an translated by M.A.S. Abdel Haleem, “The noun shahid is much more complex than the term martyr….The root of shahid conveys ‘to witness, to be present, to attend, to testify, and/or to give evidence’”.[77] Additionally, Haleem notes, that the martyrs in the Qur’an are chosen by God to witness Him in Heaven. This act of witnessing is given to those who are “given the opportunity to give evidence of the depth of their faith by sacrificing their worldly lives, and will testify with the prophets on the Day of Judgment”.[77] This is supported in Qur'an 3:140, “…if you have suffered a blow, they too have the upper hand. We deal out such days among people in turn, for God to find out who truly believes, for Him to choose martyrs from among you….”[78]

It is also stated in the Qur'an, that the scriptures in which Moses brought forth from God to the Children of Israel were seen as the light and guidance of God, himself (Qur'an 6:91). This strongly indicates that Moses died as a martyr: Moses died being a witness to God; Moses died giving his sacrifice to the worldly views of God; and Moses died in the act of conveying the message of God to the Children of Israel. Although his death remains a mystery and even though he did not act in a religious battle, he did in fact die for the causation of a Religious War. A war that showcased the messages of God through scripture.

In light of this observation, John Renard claims that Muslim tradition distinguishes three types of super-natural events: “the sign worked directly by God alone; the miracle worked through a prophet; and the marvel effected through a non-prophetic figure”.[79] If these three types of super-natural events are put into retrospect with the understanding of martyrdom and Moses, the aspect of being a martyr plays out to resemble the overall understanding of what “islam” translates to. The concept of martyrdom in Islam is linked with the entire religion of Islam. This whole process can be somehow understood if the term 'Islam' is appreciated.[76] This is because being a derivate of the Arabic root salama, which means 'surrender' and 'peace', Islam is a wholesome and peaceful submission to the will of God. Just like Moses is an example of the surrender to God, the term martyr further re-enforces the notion that through the signs, the miracle, and the marvel the ones chosen by God are in direct correlation to the lives of the prophets.

In conclusion, although the death of Moses was a mysterious claim by God; and the fact that Moses appeared to have died without partaking in some sort of physical religious battle, may lead one to believe that Moses does not deserve the entitlement of being a martyr. The framework of Moses described the spiritual quest and progress of the individual soul’s as it unfolds to reveal the relationship to God.[80] Nevertheless, because of his actions, his ability to be a witness, and his success as being a model for the Children of Israel his life was a buildup to the ideals of martyrdom. His death and his faithful obligations toward God have led his mysterious death to be an example of a true prophet and a true example of a martyrdom.

Isra and Mi'raj

During his Night Journey (Isra), Muhammad is known to have led Moses along with Jesus, Abraham and all other prophets in prayer.[81] Moses is mentioned to be among the prophets which Muhammad met during his ascension to heaven (Mi'raj) alongside Gabriel.

According to the Sunni view: Moses and Muhammad are reported to have exchanged greeting with each other and he is reported to have cried due to the fact that the followers of Muhammad were going to enter Heaven in greater numbers than his followers.[82] When God enjoined fifty prayers to the community to Muhammad and his followers, Muhammad once again encountered Moses, who asked what had been commanded by God. When Moses was told about the fifty prayers, he advised Muhammad to ask a reduction in prayers for his followers.[83] When Muhammad returned to God and asked for a reduction, he was granted his request. Once again he met Moses, who again inquired about the command of God. Despite the reduction, Moses again urged Muhammad to ask for a reduction. Muhammad again returned and asked for a reduction. This continued until only five prayers were remaining. When Moses again told Muhammad to ask for a reduction, Muhammad replied that he was shy of asking again. Therefore, the five prayers were finally enjoined upon the Muslim community.[84]

In Islamic thought

Moses is revered as a prominent prophet and messenger in Islam, his narrative is recounted the most among the prophets in the Qur'an.[85] He is regarded by Muslims as one of the five most prominent prophets in Islam along with Jesus (Isa), Abraham (Ibrahim), Noah (Nuh) and Muhammad.[86] These five prophets are known as Ulu’l azm prophets, the prophets that were favoured by God and are described in the Qur'an to be endowed with determination and perseverance. Islamic tradition describes Moses being granted many miracles, including the glowing hand and his staff which could turn into a snake. The life of Moses is often described as a parallel to that of Muhammad.[87][88] Both are regarded as being ethical and exemplary prophets. Both are regarded as lawgivers, ritual leaders, judges and the military leaders for their people. Islamic literature also identifies a parallel between their followers and the incidents of their history. The exodus of the Israelites is often viewed as a parallel to the migration of the followers of Muhammad. The drowning and destruction of the Pharaoh and his army is also described to be a parallel to the Battle of Badr.[89] In Islamic tradition along with other miracles bestowed to Moses such as the radiant hand and his staff Moses is revered as being a prophet who was specially favored by God and conversed directly with Him, unlike other prophets who received revelation by God through an intervening angel. Moses received the Torah directly from God. Despite conversing with God, the Qur'an states that Moses was unable to see God.[90] For these feats Moses is revered in Islam as Kalim Allah, meaning the one who talked with God.[91]

Revealed scripture

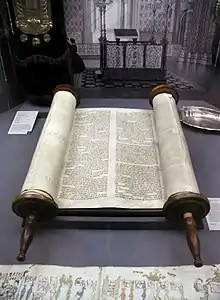

In Islam, Moses is revered as the receiver of a scripture known as the Torah (Tawrat). The Qur'an describes the Torah to be “guidance and a light" for the Israelites and that it contained teachings about the Oneness of God, prophethood and the Day of Judgment.[92] It is regarded as containing teachings and laws for the Israelites which was taught and practiced by Moses and Aaron to them. Among the books of the complete Hebrew Bible, only the Torah, meaning the books of Genesis, Deuteronomy, Numbers, Leviticus and Exodus are considered to divinely revealed instead of the whole Tanakh or the Old Testament.[93] The Qur'an mentions the Ten Commandments given to the Israelites through Moses which it claims contained guidance and understanding of all things. The Qur'an states that the Torah was the "furqan" meaning difference, a term which the Qur'an is regarded as having used for itself as well.[94] The Qur'an states that Moses preached the same message as Muhammad and the Torah foretold that arrival of Muhammad. Modern Muslim scholars such as Mark N. Swanson and David Richard Thomas cite Deuteronomy 18:15–18 as foretelling the arrival of Muhammad.[95]

Some Muslims believe that the Torah has been corrupted (tahrif).[96] The exact nature of the corruption has been discussed among scholars. The majority of Muslim scholars including Ibn Rabban and Ibn Qutayba have stated that the Torah had been distorted in its interpretation rather than in its text. The scholar Tabari considered the corruption to be caused by distortion of the meaning and interpretation of the Torah.[97] Tabari considered the learned rabbis of producing writings alongside the Torah, which were based on their own interpretations of the text.[97] The rabbis then reportedly "twisted their tongues" and made them appear as though they were from the Torah. In doing so, Al-Tabari concludes that they added to the Torah what was not originally part of it and these writings were used to denounce the prophet Muhammad and his followers.[97] Tabari also states that these writings of the rabbis were mistaken by some Jews to be part of the Torah.[97] A minority view held among scholars such as Al-Maqdisi is that the text of the Torah itself was corrupted. Maqdisi claimed that the Torah had been distorted in the time of Moses, by the seventy elders when they came down from Mount Sinai.[98] Maqdisi states that the Torah was further corrupted in the time of Ezra, when his disciples made additions and subtractions in the text narrated by Ezra. Maqdisi also stated that discrepancies between the Jewish Torah, the Samaritan Torah and the Greek Septuagint pointed to the fact that the Torah was corrupted.[98] Ibn Hazm viewed the Torah of his era as a forgery and considered various verses as contradicting other parts of the Torah and the Qur'an.[99] Ibn Hazm considered Ezra as the forger of the Torah, who dictated the Torah from his memory and made significant changes to the text.[99] Ibn Hazm accepted some verses which, he stated, foretold the arrival of Muhammad.

In religious sects

Sunni Muslims fast on the Day of Ashura (the tenth day of Muharram (the first month in the Hijri calendar as similar to Yom Kippur which is on the tenth day of Tishrei (the first month of the Hebrew civil year)) to commemorate the liberation of the Israelites from the Pharaoh.[100] Shia Muslims view Moses and his relation to Aaron as a prefiguration of the relation between Muhammad and his cousin, Ali ibn Abi Talib.[89] Ismaili Shias regard Moses as 4th in the line of the seven 'speaking prophets' (natiq), whose revealed law was for all believers to follow.[101][102] In Sufism Moses is regarded as having a special position, being described as a prophet as well as a spiritual wayfarer. The author Paul Nwyia notes that the Qur'anic accounts of Moses have inspired Sufi exegetes to "meditate upon his experience as being the entry into a direct relationship with God, so that later the Sufis would come to regard him as the perfect mystic called to enter into the mystery of God".[103] Muslim scholars such as Norman Solomon and Timothy Winter state without naming that some Sufi commentators excused Moses from the consequence of his request to be granted a vision of God, as they considered that it was "the ecstasy of hearing God which compelled him to seek completion of union through vision".[103] The Qur'anic account of the meeting of Moses and Khidr is also noted by Muslim writers as being of special importance in Sufi tradition. Some writers such as John Renard and Phyllis G. Jestice note that Sufi exegetes often explain the narrative by associating Moses for possessing exoteric knowledge while attributing esoteric knowledge to Khidr.[104][105] The author John Renard states that Sufis consider this as a lesson, "to endure his apparently draconian authority in view of higher meanings".[104]

In Islamic literature

| Lineage of several prophets according to Islamic tradition |

|---|

| Dotted lines indicate multiple generations |

Moses is also revered in Islamic literature, which narrates and explains different parts of the life of Moses. The Muslim scholar and mystic Rumi, who titles Moses as the "spirit enkindler" also includes a story of Moses and a shepherd in his book, the Masnavi.[22][106] The story narrates the horror of Moses, when he encounters a shepherd who is engaged in anthropomorphic devotions to God.[107] Moses accuses the shepherd of blasphemy; when the shepherd repents and leaves, Moses is rebuked by God for "having parted one of His servants from Him". Moses seeks out the shepherd and informs him that he was correct in his prayers. The authors Norman Solomon and Timothy Winter regard the story to be "intended as criticism of and warning to those who in order to avoid anthropomorphism, negate the Divine attributes".[22] Rumi mainly mentions the life of Moses by his encounter with the burning tree, his white hand, his struggle with the Pharaoh and his conversation with God on Mount Sinai. According to Rumi, when Moses came across the tree in the valley of Tuwa and perceived the tree consumed by fire, he in fact saw the light of a "hundred dawns and sunrises".[108] Rumi considered the light a "theater" of God and the personification of the love of God. Many versions of the conversation of Moses and God are presented by Rumi; in all versions Moses is commanded to remove his footwear, which is interpreted to mean his attention to the world. Rumi commented on Qur'an 4:162[109]} considering the speech of God to be in a form accessible only to prophets instead of verbal sounds.[108] Rumi considers the miracles given to Moses as assurance to him of the success of his prophethood and as a means of persuasion to him to accept his mission. Rumi regarded Moses as the most important of the messenger-prophets before Muhammad.[110]

The Shi'a Qur'anic exegesis scholar and thinker Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei, in his commentary Balance of Judgment on the Exegesis of the Qur'an attempted to show the infallibility of Moses in regard to his request for a vision of God and his breaking of his promise to Khidr as a part of the Shi'a doctorine of prophetic infallibility (Ismah).[22] Tabatabaei attempted to solve the problem of vision by using various philosophical and theological arguments to state that the vision for God meant a necessary need for knowledge. According to Tabatabaei, Moses was not responsible for the promise broken to Khidr as he had added "God willing" after his promise.[22] The Islamic reformist and activist Sayyid Qutb, also mentions Moses in his work, In the Shade of the Qur'an.[22] Sayyid Qutb interpreted the narrative of Moses, keeping in view the sociological and political problems facing the Islamic world in his era; he considered the narrative of Moses to contain teachings and lessons for the problems which faced the Muslims of his era.[22] According to Sayyid Qutb, when Moses was preaching to the Pharaoh, he was entering the "battle between faith and oppression". Qutb believed that Moses was an important figure in Islamic teachings as his narrative symbolized the struggle to "expel evil and establish righteousness in the world" which included the struggle from oppessive tyrants, a struggle which Qutb considered was the core teaching of the Islamic faith.[22]

The Sixth Imam, Ja'far al-Sadiq, regarded the journey of Moses to Midian and to the valley of Tuwa as a spiritual journey.[103] The turning of the face of Moses towards Midian is stated to be the turning of his heart towards God. His prayer to God asking for help of is described to be his awareness of his need. The commentary alleged to the Sixth Imam then states the command to remove his shoes symbolized the command to remove everything from his heart except God.[103] These attributes are stated to result in him being honoured by God's speech.[103] The Andalusian Sufi mystic and philosopher, Ibn Arabi wrote about Moses in his book The Bezels of Wisdom dedicating a chapter discussing "the Wisdom of Eminence in the word of Moses". Ibn Arabi considered Moses to be a "fusion" of the infants murdered by the Pharaoh, stating that the spiritual reward which God had chosen for each of the infants manifested in the character of Moses. According to Ibn Arabi, Moses was from birth an "amalgam" of younger spirits acting on older ones.[111] Ibn Arabi considered the ark to be the personification of his humanity while the water of the river Nile to signifiy his imagination, rational thought and sense perception.[112]

Burial place

The grave of Moses is located at Maqam El-Nabi Musa,[113] which lies 11 km (6.8 mi) south of Jericho and 20 km (12 mi) east of Jerusalem in the Judean wilderness.[114] A side road to the right of the main Jerusalem-Jericho road, about 2 km (1.2 mi) beyond the sign indicating sea level, leads to the site. The Fatimid, Taiyabi and Dawoodi Bohra sects also believe in the same.[115]

The main body of the present shrine, mosque, minaret and some rooms were built during the reign of Baibars, a Mamluk Sultan, in 1270 AD. Over the years Nabi Musa was expanded,[115] protected by walls, and includes 120 rooms in its two levels which hosted the visitors.

Qur'anic references

- Appraisals of Moses: 2:136, 4:164, 6:84, 6:154, 7:134, 7:142, 19:51, 20:9, 20:13, 20:36, 20:41, 25:35, 26:1, 26:21, 27:8, 28:7, 28:14, 33:69, 37:114, 37:118, 44:17

- Moses' attributes: Q7:150, Q20:94, Q28:15, Q28:19, Q28:26

- Moses' prophecy: Q7:144, Q20:10-24, Q26:10, Q26:21, Q27:7-12, Q28:2-35, Q28:46, Q79:15-19

- The prophet whom God spoke to: Q2:253, Q4:164, Q7:143-144, Q19:52, Q20:11-24, Q20:83-84, Q26:10-16, Q27:8-11, Q28:30-35, Q28:46, Q79:16-19

- The Torah: Q2:41-44, Q2:53, Q2:87, Q3:3, Q3:48, Q3:50, Q3:65, Q3:93, Q5:43-46, Q5:66-68, Q5:110, Q6:91, Q6:154-157, Q7:145, Q7:154-157, Q9:111, Q11:110, Q17:2, Q21:48, Q23:49, Q25:3, Q28:43, Q32:23, Q37:117, Q40:53, Q41:45, Q46:12, Q48:29, Q53:36, Q61:6, Q62:5 Q87:19

- The valley: Q20:12, Q20:20, Q28:30, Q79:16

- Moses' miracle: Q2:56, Q2:60, Q2:92, Q2:211, Q7:107-108, Q7:117-120, Q7:160, Q11:96, Q17:101, Q20:17-22, Q20:69, Q20:77, Q26:30-33, Q26:45, Q26:63, Q27:10-12, Q27:12, Q28:31-32, Q40:23, Q40:28, Q43:46, Q44:19, Q44:33, Q51:38, Q79:20

- Moses and the Pharaoh

- Moses' life inside the palace: Q20:38-39, Q26:18, Q28:8-12

- Returned to his mother: Q20:4, Q28:12-13

- God's revelation to Moses' mother: Q20:38-39, Q28:7-10

- Moses' preaching: Q7:103-129, Q10:84, Q20:24, Q20:42-51, Q23:45, Q26:10-22, Q28:3, Q43:46, Q44:18, Q51:38, Q73:15-17

- Moses met the Pharaoh: Q20:58-59, Q20:64-66, Q26:38-44

- The Pharaoh's magicians: Q7:111-116, Q10:79-80, Q20:60-64, Q26:37-44

- Moses vs. the magicians: Q7:115-122, Q10:80-81, Q20:61-70, Q26:43-48

- Dispute among the magicians: Q20:62, Q26:44-47

- Moses warned the magicians: Q10:81, Q20:61

- Moses and Aaron were suspected to be magicians too: Q7:109, Q7:132, Q10:7-77, Q17:101, Q20:63, Q40:24, Q43:49

- Belief of the magicians: Q7:119-126, Q20:70-73, Q26:46

- The belief of Asiya: Q66:11

- Trial to Pharaoh's family: Q7:130-135

- Pharaoh's weakness: Q7:103-126, Q10:75, Q11:97-98, Q17:102, Q20:51-71, Q23:46-47, Q25:36, Q26:11, Q26:23-49, Q28:36-39, Q29:39, Q38:12, Q40:24-37, Q43:51-54, Q44:17-22, Q50:13, Q51:39, Q54:41-42, Q69:9, Q73:16, Q79:21-24

- Moses and his followers went away: Q20:77, Q26:52-63, Q44:23-24

- Moses and his followers were safe: Q2:50, Q7:138, Q10:90, Q17:103, Q20:78-80, Q26:65, Q37:115-116, Q44:30-31

- Pharaoh's belief was too late: Q10:90

- Pharaoh's and his army: Q2:50, Q3:11, Q7:136-137, Q8:52-54, Q10:88-92, Q17:103, Q20:78-79, Q23:48, Q25:36,Q26:64-66, Q28:40, Q29:40, Q40:45, Q43:55-56, Q44:24-29, Q51:40, Q54:42, Q69:10, Q73:16, Q79:25, Q85:17-18, Q89:13

- Believer among Pharaoh's family: Q40:28-45

- The Pharaoh punished the Israelites: Q2:49, Q7:124-141, Q10:83, Q14:6, Q20:71, Q26:22, Q26:49, Q28:4, Q40:25

- The Pharaohs and Haman were among the rejected: Q10:83, Q11:97, Q28:4-8, Q28:32, Q28:42, Q29:39, Q40:36, Q44:31

- Moses killed an Egyptian: Q20:40, Q26:19-21, Q28:15-19, Q28:33

- Moses' journey to Median:

- The people who insulted Moses:Q33:69

- Travel to the Promised Land

- The Israelites entered the Promised Land: Q2:58, Q5:21-23,

- Moses' dialogue with God: Q2:51, Q7:142-143, Q7:155, Q20:83-84

- The Israelites worshipped the calf: Q2:51-54, Q2:92-93, Q4:153, Q7:148-152, Q20:85-92

- Seven Israelites with Moses met God: Q7:155

- Moses and Samiri: Q20:95-97

- God manifested himself to the mountain: Q7:143

- Refusal of the Israelites: Q2:246-249, Q3:111, Q5:22-24, Q59:14

- Attributes of the Israelites: Q2:41-44, Q2:55-59, Q2:61-71, Q2:74-76, Q2:83, Q2:93-6,Q2:100-101, Q2:104, Q2:108, Q2:140-142, Q2:246-249, Q3:24, Q3:71, Q3:75, Q3:112, Q3:181, Q3:183, Q4:44, Q4:46-47, Q4:49, Q4:51, Q4:53-54, Q4:153, Q4:155-156, Q4:161, Q5:13, Q5:20, Q5:24, Q5:42-43, Q5:57-58, Q5:62-64, Q5:70, Q5:79-82, Q7:134, Q7:138-139, Q7:149, Q7:160, Q7:162-163}, Q7:169, Q9:30, Q9:34, Q16:118, Q17:4, Q17:101, Q20:85-87, Q20:92, Q58:8, Q59:14

- Moses and Khidir: Q18:60-82

- Qarun: Q28:76-82, Q29:39-40

See also

- Biblical narratives and the Quran# Moses— Comparison between the Quranic and Biblical accounts of Moses.

- Moses in rabbinic literature— A rabbinic view of Moses and his life.

- Moses in Judeo-Hellenistic literature

- Burning bush— The bush through which some believe God spoke to Moses.

- Scrolls of Moses—Another scripture believed to be given to Moses in Islam.

- Tawrat—an Islamic view of the Torah.

- Ten Commandments— the ten commandments given to Moses on Mount Sinai.

- Prophets of Islam—for other characters viewed as Prophets in Islam.

- Aaron— also known as Harun, the brother of Moses.

- Amram— the father of Moses and Aaron.

- Jochebed— also known as Aisha the mother of Moses and Aaron in Biblical tradition.

- Miriam— the sister of Moses in Biblical tradition.

References

- Meddeb, Abdelwahab; Stora, Benjamin (27 November 2013). A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations: From the Origins to the Present Day. ISBN 9781400849130. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Ltd, Hymns Ancient Modern (May 1996). Third Way (magazine). p. 18. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Annabel Keeler, "Moses from a Muslim Perspective", in: Solomon, Norman; Harries, Richard; Winter, Tim (eds.), Abraham's children: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in conversation Archived 29 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, T&T Clark Publ. (2005), pp. 55–66.

- Quran 19:51–53

- Maulana Muhammad Ali (2011). Introduction to the Study of The Holy Qur'an. p. 113. ISBN 9781934271216. Archived from the original on 29 October 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Malcolm Clark (2011). Islam for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 101. ISBN 9781118053966. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Arij A. Roest Crollius (1974). Documenta Missionalia – The Word in the Experience of Revelation in the Qur'an and Hindu scriptures. Gregorian&Biblical BookShop. p. 120. ISBN 9788876524752. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Clinton Bennett (2010). Studying Islam: The Critical Issues. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 36. ISBN 9780826495501. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Sahih Muslim, 1:309, 1:314

- Stories of the Prophets, Ibn Kathir, The Story of Moses, c. 1350 C.E.

- Kelly Bulkeley; Kate Adams; Patricia M. Davis (2009). Dreaming in Christianity and Islam: Culture, Conflict, and Creativity. Rutgers University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780813546100. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Islam qwZbn0C&pg=PA17. AuthorHouse. 2012. ISBN 9781456797485.

- Brannon .M. Wheeler (2002). Prophets in the Qur'an, introduction to the Qur'an and Muslim exegesis. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 174. ISBN 9780826449573. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Abdul-Sahib Al-Hasani Al-'amili. The Prophets, Their Lives and Their Stories. Forgotten Books. p. 282. ISBN 9781605067063. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 28:7

- "Quran translation Comparison |Quran 28:9 | Alim". www.alim.org. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- Ergun Mehmet Caner; Erir Fethi Caner; Richard Land (2009). Unveiling Islam: An Insider's Look at Muslim Life and Beliefs. Kregel Publications. p. 88. ISBN 9780825424281. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Avner Gilʻadi (1999). Infants, Parents and Wet Nurses: Medieval Islamic Views on Breastfeeding and Their Social Implications. Brill Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 9789004112230. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Raouf Ghattas; Carol Ghattas (2009). A Christian Guide to the Qur'an: Building Bridges in Muslim Evangelism. Kregel Academic & Professional. p. 212. ISBN 9780825426889. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Oliver Leaman (2 May 2006). The Qur'an: an encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 433. ISBN 9781134339754. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Patrick Hughes; Thomas Patrick Hughes (1995). Dictionary of Islam. Asian Educational Services. p. 365. ISBN 9788120606722. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Norman Solomon; Richard Harries; Tim Winter (2005). Abraham's Children: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conversation. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 63–66. ISBN 9780567081612. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- M. The Houtsma (1993). First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913–1936. Brill Academic Pub. p. 739. ISBN 9789004097964. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Abdul-Sahib Al-Hasani Al-'amili. The Prophets, Their Lives and Their Stories. Forgotten Books. p. 277. ISBN 9781605067063. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Naeem Abdullah (2011). Concepts of Islam. Xlibris Corporation. p. 89. ISBN 9781456852436. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Maulana Muhammad Ali (2011). The Religion of Islam. p. 197. ISBN 9781934271186. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Yousuf N. Lalljee (1993). Know Your Islam. TTQ, Inc. pp. 77–78. ISBN 9780940368026. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Patrick Laude (2011). Universal Dimensions of Islam: Studies in Comparative Religion. World Wisdom, Inc. p. 31. ISBN 9781935493570. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Andrea C. Paterson (2009). Three Monotheistic Faiths – Judaism, Christianity, Islam: An Analysis And Brief History. AuthorHouse. p. 112. ISBN 9781434392466. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Jaʻfar Subḥānī; Reza Shah-Kazemi (2001). Doctrines of Shiʻi Islam: A Compendium of Imami Beliefs and Practices. I.B.Tauris. p. 67. ISBN 9781860647802. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 20:50 Quran 20:50

- Quran 20:51 Quran 20:51–52

- Quran 26:23 Quran 26:23

- Heribert Husse (1998). Islam, Judaism, and Christianity: Theological and Historical Affiliations. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 94. ISBN 9781558761445.

- Sohaib Sultan (2011). "Meeting Pharaoh". The Koran For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 131. ISBN 9781118053980. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Heribert Busse (1998). Islam, Judaism, and Christianity: Theological and Historical Afflictions. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 95. ISBN 9781558761445.

- Moiz Ansari (2006). Islam And the Paranormal: What Does Islam Says About the Supernatural in light of the Qur'an, Sunnah and Hadith. iUniverse, Inc. p. 185. ISBN 9780595378852. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Francis E.Peters (1993). A Reader on Classical Islam. Princeton University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780691000404. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Raouf Ghattas; Carol Ghattas (2009). A Christian Guide to the Qur'an: Building Bridges in Muslim Evangelism. Kregel Academic. p. 179. ISBN 9780825426889. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 28:38 Quran 28:38

- Heribert Busse (1998). Islam, Judaism, and Christianity:Theological and Historical Affiliations. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 97. ISBN 9781558761445.

- Patrick Hughes; Thomas Patrick Hughes (1995). Dictionary of Islam. Asian Educational Services. p. 459. ISBN 9788120606722. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Raouf Ghattas; Carol Ghattas (2009). A Christian Guide to the Quran:Building Bridges in Muslim Evangelism. Kregel Academic. p. 125. ISBN 9780825426889. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 7:136

- Halim Ozkaptan (2010). Islam and the Koran- Described and Defended. p. 41. ISBN 9780557740437. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- "Quran translation Comparison | Quran 10:90 | Alim". www.alim.org. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Francis.E.Peters (1993). A Reader on Classical Islam. Princeton University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780691000404. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Brannon.M.Wheeler (2002). Moses in the Quran and Islamic Exegesis. Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 9780700716036. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 2:60 Quran 2:60

- Kenneth.W.Morgan (1987). Islam, the Straight Path: Islam interpreted by Muslims. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 98. ISBN 9788120804036. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 7:143 Quran 7:143

- Iftikhar Ahmed Mehar (2003). Al-Islam: Inception to Conclusion. BookSurge Publishing. p. 121. ISBN 9781410732729. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 20:85 Quran 20:85–88

- Patrick Hughes; Thomas Patrick Hughes (1995). Dictionary of Islam. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120606722. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Brannon M. Wheeler (2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 205. ISBN 9780826449566. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Elwood Morris Wherry; George Sale (2001). A Comprehensive Commentary on the Quran: Comprising Sale's Translation and Preliminary Discourse with Additional Notes and Emendations. Volume 1. Routledge. p. 314. ISBN 9780415245272. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Zeʼev Maghen (2006). After Hardship Cometh Ease: The Jews As Backdrop for Muslim Moderation. Walter De Gruyter Inc. p. 136. ISBN 9783110184549. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Zeʼev Maghen (2006). After Hardship Cometh Ease: The Jews As Backdrop for Muslim Moderation. Walter De Gruyter Inc. p. 133. ISBN 9783110184549. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 2:68 Quran 2:68

- John Miller; Aaron Kenedi; Thomas Moore (2000). God's Breath: Sacred Scriptures of the World – The Essential Texts of Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Sufism. Da Capo Press. p. 406. ISBN 9781569246184. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Patrick Hughes; Thomas Patrick Hughes (1995). Dictionary Of Islam. Asian Educational Services. p. 364. ISBN 9788120606722. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (Maulana), Jawid Ahmad Mojaddedi (2007). The Masnavi. Oxford University Press. p. 237. ISBN 9780199212590. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Felicia Norton Charles Smith (2008). An Emerald Earth: Cultivating a Natural Spirituality and Serving Creative Beauty in Our World. TwoSeasJoin Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9780615235462. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Quran 18:66 Quran 18:66

- John Renard (2008). Friends of God: Islamic Images of Piety, Commitment, and Servanthood. University of California Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780520251984. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Muhammad Hisham Kabbani (2003). Classical Islam And The Naqshbandi Sufi Tradition. Islamic Supreme Council of America. p. 155. ISBN 9781930409101. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Gerald T. Elmore (1999). Islamic Sainthood in the Fullness of Time: Ibn Al-Arabi's Book of the Fabulous Gryphon. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 491. ISBN 9789004109919. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 1:5:277

- edited by M. Th. Houtsma (1993). E.J Brill's First Encyclopedia of Islam (1913–1936). 4. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 570. ISBN 9789004097902. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 2:23:423

- al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1987). The History of al-Tabari: The Chrilden of Israel. Albany, New York: State University of New York. p. 86. ISBN 0791406881.

- al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1987). The History of al-Tabari: The Children of Israel. Albany, New Yoro: State University of New York. p. 86. ISBN 0791406881.

- al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1987). The History of al-Tabari: The Children of Israel. Albany, New York: State University of New York. p. 86. ISBN 0791406881.

- al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1987). The History of al-Tabari:The Children of Israel. Albany, New York: State University of New York. p. 86. ISBN 0791406881.

- Brettler, Marc Zvi (2011). The Jewish Annotated New Testament New Revised Standard Version Bible Translation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195297706.

- "The Concept of Martyrdom in Islam". Al-Islam.org. Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- Haleem, M.A.S. Abdel (2011). The Qur'an: A New Translation. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780199535958.

- Haleem, M.A.S. Abdel (2011). The Qur'an: A New Translation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199535958.

- Renard, John (2011). Islam and Christianity: Theological Themes in Comparative Perspective. California: University of California Press. p. 197. ISBN 9780520266780.

- Renard, John (2011). Islam and Christianity: Theological Themes in Comparative Perspective. California: University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780520266780.

- Spencer C. Tucker (2010). The Encyclopedia of Middle East Wars: The United States in the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq Conflicts, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 1885. ISBN 9781851099474. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Diane Morgan (2010). Essential Islam: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice. ABC-CLIO. p. 118. ISBN 9780313360251.

- Matt Stefon (2009). Islamic Beliefs And Practices. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 9781615300174. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Andrew Rippin; Jan Knappert (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Islam. University Of Chicago Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780226720630. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Norman L. Geisler; Abdul Saleeb (2002). Answering Islam: The Crescent in Light of the Cross. Baker Books. p. 56. ISBN 9780801064302. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- George W. Braswell (2000). What You Need to Know About Islam and Muslims. p. 22. ISBN 9780805418293. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Juan Eduardo Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 483. ISBN 9781438126968. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Norman Solomon; Richard Harries; Tim Winter (2006). Abraham's Children: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conversation. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 67. ISBN 9780567081612. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Juan Eduardo Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 483. ISBN 9781438126968. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Mohammad Zia Ullah (1984). Islamic Concept of God. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 9780710300768. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- James E. Lindsay (2005). Daily Life In The Medieval Islamic World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 178. ISBN 9780313322709. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Quran 5:44 Quran 5:44

- Vincent J. Cornell (2006). Voices of Islam. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 36. ISBN 9780275987329. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- David Marshall (1999). God, Muhammad and the Unbelievers. Routledge. p. 136.

- Emmanouela Grypeou; Mark N. Swanson; David Richard Thomas (2006). The Encounter of Eastern Christianity With Early Islam. Baker Books. p. 300. ISBN 9789004149380. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Camilla Adang (1996). Muslim Writers on Judaism and the Hebrew Bible: From Ibn Rabban to Ibn Hazm. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 223. ISBN 9789004100343. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Camilla Adang (1996). Muslim Writers on Judaism and the Hebrew Bible: From Ibn Rabban to Ibn Hazm. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 229. ISBN 9004100342. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Jacques Waardenburg (1999). Muslim Perceptions of Other Religions: A Historical Survey. Oxford University Press. p. 150. ISBN 9780195355765. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Jacques Waardenburg (1999). Muslim Perceptions of Other Religions:A Historical Survey. Oxford University Press. pp. 153–154. ISBN 9780195355765. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Marion Katz (2007). The Birth of The Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 9780415771276. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Juan Eduardo Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 483. ISBN 9781438126968. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Henry Corbin (1983). Cyclical Time & Ismaili Gnosis. p. 189. ISBN 9780710300485. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Norman Solomon; Timothy Winter (2006). Paul Nwyia in "Moses in Sufi Tradition",: Abraham's Children: Jews, Christians and Muslims in Conversation. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9780567081612. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- John Renard (2009). The A to Z of Sufism. Scarecrow Press. p. 137. ISBN 9780810868274. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Phyllis G. Jestice (2004). Holy People of the World: A Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 475. ISBN 9781576073551. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Suresh K. Sharma; Usha Sharma (2004). Cultural and Religious Heritage of India: Islam. Mittal Publications. p. 283. ISBN 9788170999607. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Mehmet Fuat Köprülü; Gary Leiser; Robert Dankoff (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Routledge. p. 360. ISBN 9780415366861. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- John Renard (1994). All the King's Falcons: Rumi on Prophets and Revelation. SUNY Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780791422212. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- {{cite quran|4|162|s=ns|b=n}

- John Renard (1994). All the King's Falcons: Rumi on Prophets and Revelation. SUNY Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780791422212. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Ibn al-ʻArabī; R. W. J. Austin (1980). Bezels of Wisdom. Paulist Press. pp. 251–252. ISBN 0809123312.

- Salman H.Bashier (2011). The Story of Islamic Philosophy: Ibn Tufayl, Ibn Al-'Arabi, and Others on the Limit Between Naturalism and Traditionalism. State University of New York Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-1438437439. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Silvani, written and researched by Daniel Jacobs ... Shirley Eber and Francesca (1998). Israel and the Palestinian Territories : the rough guide (2nd ed.). London: Penguin Books. pp. 531. ISBN 1858282489.

burial place of prophet musa.

- Amelia Thomas; Michael Kohn; Miriam Raphael; Dan Savery Raz (2010). Israël & the Palestinian Territories. Lonely Planet. pp. 319. ISBN 9781741044560.

- Urbain Vermeulen (2001). Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid, and Mamluk Eras III: Proceedings of the 6th, 7th and 8th International Colloquium Organized at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in May 1997, 1998, and 1999. Peeters Publishers. p. 364. ISBN 9789042909700. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.