Kurdish literature

Kurdish literature (in Kurmanji: Wêjeya Kurdî, in Sorani: وێژەی کوردی or ئەدەبی کوردی) is literature written in the Kurdish languages. Literary Kurdish works have been written in each of the four main languages: Zaza, Gorani, Kurmanji and Sorani. Ali Hariri (1009-1079) is one of the first well-known poets who wrote in Kurdish.[1] He was from the Hakkari region.[2]

|

Zazaki - Gorani literature

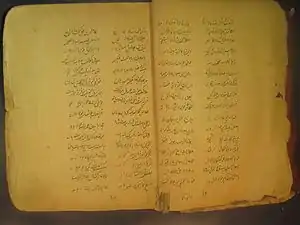

Some of the earliest texts written in Kurdish are in the Hawrami dialects. The earliest of these are the classical poems attributed to Elder Shalyar the son of Jamasb, an ancient Zoroastrian priest who lived in the Horaman region. His works are said to date back to several centuries before Christ, as far back as 600 BC. His literary works are collected in what is called "marefat".[3][4]

One of the first literary works in Kurdish is a poem from the 7th century, written in the Hawremani dialect. The poem, called Hurmizgan, talks about invading Muslims.[5][6] Some of the well-known Gorani language poets and writers are Parishan Dinawari (d. ca. 1395), Mustafa Besarani (1642–1701), Muhammad Kandulayi (late 17th century), Khana Qubadi (1700–1759), Shayda Awrami (1784–1852) and Mastoureh Ardalan) (1805–1848). Zazaki and Gorani which was the literary languages of much of what today is known as Iraqi, Turkish and Iranian Kurdistan, is classified as a member of the Zaza–Gorani branch of the Northwestern Iranian languages.[7]

Kurmanji literature

A Yezidi religious work, the Meshefa Reş, is in a classic form of Kurmanji[8] and it has been conjectued that it was written sometime in the 13th century. However, it has been argued that the work was actually written as late as the 20th century by non-Yazidi authors seeking to summarise the beliefs of Yezidis in a form similar to that of the holy scriptures of other religions.[9]

The Kurdish poet Muhammad Faqi Tayran (1590–1660) collected many folk stories in his book In the Words of the Black Horse. He also wrote a book of Sufi verse, The Story of Shaykh of San’ân. Faqi-Tayran also had versified correspondence with the poet Malaye Jaziri. Some of the well-known Kurmanji poets and writers are listed below.

- Ali Hariri (1009-1079).

- Mela Hesenê Bateyî (1417–1494) from Hakkari region, who wrote the author of Mawlud, a collection of verse and an anthology;

- Salim Salman, author of Yûsif û Zuleyxa in 1586;

- Malaye Jaziri (1570–1640) from Buhtan region, the famous sufi poet. His collection of poems contains more than 2,000 verses

- Ahmad Khani (1651–1707), the author of Mam and Zin, a long poem of 2,650 distichs, is probably the best known and most popular of the classical Kurdish poets.[10]

- Ismail Bayazidi (1654–1710), author of a Kurmanji-Arabic-Persian dictionary for children, entitled Guljen.

The tragedy of Mam and Zin

The drama of Mem û Zîn (Mam and Zin) (Memî Alan û Zînî Buhtan), was written in 1694 by Ahmad Khani (1651–1707) from Hakkari, is a rich source of Kurdish culture, history and mythology. This work also emphasizes the national aspirations of the Kurdish people.

Mam of the Alan clan and Zin of Buhtan family are two lovers from Alan and Butan families, respectively. Their union is blocked by a person named Bakr of the Bakran clan. Mam eventually dies during a complicated conspiracy by Bakr. When Zin receives the news, she also dies while mourning the death of Mam on his grave. The immense grief leads to her death and she is buried next to Mam. The news of the death of Mam and Zin, spreads quickly among the people of Jazira Butan. Then Bakr's role in the tragedy is revealed, and he takes sanctuary between the two graves. He is eventually captured and slain by the people of Jazira. A thorn bush soon grows out of Bakr's blood, sending its roots of malice deep into the earth between the lovers’ graves, separating the two even after their death.

Contemporary Kurmanji literature

The first Kurmanji newspaper, titled Kurdistan, was published in Cairo in 1898. The Kurds in the Soviet Union, despite their small numbers, had the opportunity of elementary and university education in Kurdish and for many decades. This in turn led to an appearance of several Kurdish writers and researchers among them. The literary works of Qanate Kurdo and Arab Shamilov are the well known examples of Kurdish prose in the 20th century. The first modern Latin-based alphabet for Kurdish was created by Celadet Alî Bedirxan, the linguist and writer who fled Turkey in the 1920s and spent the rest of his life in Syria.

Since the 1970s, there has been a massive effort on the part of Kurds in Turkey to write and to create literary works in Kurdish. The amount of printed material during the last three decades has increased enormously. Many of these activities were centered in Europe particularly Sweden and Germany where many of the immigrant Kurds are living. There are a number of Kurdish publishers in Sweden, partly supported by the Swedish Government. More than two hundred Kurdish titles have appeared in the 1990s. Some of the well known contemporary Kurdish writers from Turkey are Firat Cewerî, Mehmed Uzun, Abdusamet Yigit, Mehmed Emin Bozarslan, Mahmud Baksi, Hesenê Metê, Yekta Uzunoglu (Geylani),[11] Arjen Arî and Rojen Barnas.

The main academic center for Kurdish literature and language in Europe is the Kurdish Institute of Paris (Institut Kurde de Paris) founded in 1983. A large number of Kurdish intellectuals and writers from Europe, America and Australia are contributing to the efforts carried out by the Institute for reviving Kurdish language and literature.

Sorani literature

In contrast to Kurmanji, literary works in Sorani were not abundant before the late 18th century and early 19th century. Although many poets Nalî have written in Sorani,[12] but it was only after him that Sorani became an important dialect in writing.[13] Nalî was the first poet to write a diwan in this dialect. Others, such as Salim and Kurdi, wrote in Sorani in the early 19th century as well.[14] Haji Qadir Koyi of Koy Sanjaq in central Kurdistan (1817–1897), and Sheikh Reza Talabani (1835–1909) also wrote in Sorani dialect after Nalî. The closeness of the two dialects of Sorani and Kurmanji is cited as one of the reasons for the late start in Sorani literature, as well as the fact that during 15th to 19th century, there was a rich literary tradition in the Kurmanji dialect. Furthermore the presence of the Gorani dialect as a literary language and its connection to Yarsanism and Ardalan dynasty was another reason that people did not produce texts in Sorani.[12][15]

Despite its late start, Sorani literature progressed with a rapid pace, especially during the early 20th century and after recognition of Sorani as the main language of Kurds in Iraq. The language rights of Kurds were guaranteed by the British and school education in Kurdish started in earnest in the early 1920s. It is estimated that almost 80% of the existing Kurdish literature in the 20th century has been written in Sorani dialect.

Increased contact with the Arab world and subsequently western world led to a translation movement among Kurds in Iraqi Kurdistan in the early 20th century. Many classical literary works of Europe were translated into Sorani, including the works of Pushkin, Schiller, Byron and Lamartine.

Kurdish is one of the official languages of Iraq and the central government assistance has been instrumental in supporting publication of books and magazines in Kurdish. In the 1970s, an organization called Korî Zaniyarî Kurd (the Kurdish Science Council) was established for academic studies in Kurdish language and literature. It was centered in Baghdad. Kurdish language departments were also opened in some Iraqi universities including Baghdad University, University of Salahaddin and University of Sulaimani. Well-known Sorani poets include Abdulla Goran (founder of the free verse poetry in Kurdish), Sherko Bekas, Abdulla Pashew, Qanih. Many Kurdish writers have written novels, plays and literary analysis including Piramerd, Alaaddin Sajadi, Bakhtyar Ali, Ibrahim Ahmad, Karim Hisami and Hejar. Suzan Samancı

A historical list of Kurdish literature and poets

Religious

- Mishefa Reş, The religious book of the Êzidî (Yezidi) Kurds.[16] (in French) It is held to have been written by Shaykh Hasan (born ca. AD 1195), a nephew of Shaykh Adi ibn Musâfir, the sacred prophet of the Yezidis. However, it has been argued that it was actually written in the 20th century by Kurds who were not themselves Yezidis.[9]

- Serencam, The book of Yarsan.

- Abdussamed Babek

Zazaki - Goranî dialect

- Mala Pareshan (14th century)

- Khana Qubadi (Xana Qubadî) (1700–1759),

- Sarhang Almas Khan (17th and 18th century)

- Mastoureh Ardalan (Mestûrey Erdelan) (1805–1848)

- Mawlawi Tawagozi (Mewlewî Tawegozî ) (1806–1882)

Famous poets in Kurmancî dialect

- Mela Hesenê Bateyî (Melayê Bateyî) (1417–1491) of Hekkarî, the author of Mewlûda Kurmancî (Birthday in Kurmanji), a collection of poems.

- Melayê Cizîrî (Mela Ehmedê Cizîrî) (1570–1640) of Buhtan region, poet and sufi.

- Faqi Tayran (Feqiyê Teyran) (1590–1660) Student of Melayê Cezîrî. He is credited for contributing the earliest literary account of the Battle of Dimdim in 1609-1610 between Kurds and Safavid Empire.

- Ahmad Khani (Ehmedê Xanî) (1651–1707) (The epic drama of Mem û Zîn) (Born in Hakkari, Turkey)

- Mehmûd Bayazîdî (Mahmud Bayazidi), (1797–1859 ) Kurdish writer.

Soranî dialect

- Nalî (1798–1855)

- Haji Qadir Koyi (Hacî Qadir Koyî) (1817–1897)

- Sheikh Rezza Talabani (Şêx Reza Talebanî) (1835–1910)

- Mahwi (1830–1906)

- Wafaei (1844–1902)

Kurdish poets and writers of the 20th century

- Nari Mela Kake Heme(1874-1944) Poet, born and died in Marivan

- Piramerd or Pîremêrd (Tewfîq Beg Mehmûd Axa) (1867–1950) Poet, Writer, Playwright and Journalist.

- Celadet Alî Bedirxan (1893–1951) Writer, journalist and linguist. Creator of the modern Kurmanji alphabet.

- Arab Shamilov (Erebê Şemo) (1897–1978). Kurdish novelist in Armenia.

- Cigerxwîn or Cegerxwîn(Jigarkhwin) (Sheikmous Hasan) (1903–1984) poet, born in Mardin, Ottoman. Died in Sweden.

- Abdulla Goran (1904–1962). The founder of modern Kurdish poetry.

- Osman Sabri (1905–1993) Kurdish poet, writer and journalist, Turkey/Syria.

- Nado Makhmudov (1907–1990) Kurdish writer and public figure, Armenia.

- Hemin Mukriyani(Hêmin Mukriyanî)(1920–1986) Poet and Journalist, Iran.

- Hejar (Abdurrahman Sharafkandi) (1920–1990), Poet, Writer, Translator and Linguist, Iran.

- Jamal Nebez (1933- ) Writer, Linguist, Translator and Academic, Germany.

- Sherko Bekas (Şêrko Bêkes) (1940- ) Poet, Iraqi Kurdistan. His poems have been translated to over 10 languages.

- Latif Halmat (Letîf Helmet) (1947- ) Poet, Iraqi Kurdistan.

- Sara Omar novelist, Iraqi Kurdistan and Denmark.

- Abdulla Pashew (Ebdulla Peşêw) (1947- ) Poet.

- Alan Rubar (1948- ) Poet and translator. Born in Irani Kurdistan, Sardasht.

- Salim Barakat (1951-) Poet, Writer, and Novelist.

- Rafiq Sabir (1950- ) Poet, Sweden.

- Mehmed Uzun (1953–2007), Contemporary Writer and Novelist.

- Firat Cewerî (1959- ), Contemporary Writer and Novelist.

- Kovan Sindî (1965-), Poet and Novelist.

- Jan Dost (1965-), writer and Novelist

- İbrahim Halil Baran (1981-), Poet, writer and designer.

- Evdile Koçer (1977-), writer.

- Azad Zal (1972-) Writer-journalist-translator-poet-linguist and lexicographer

- Yekta Uzunoglu ( Geylani) (*1953) Contemporary Author-journalist-translator-poet-linguist and novelist, Prague

- Zhila Hoseini (1964–1996). Among the first women poets that composed modern poems in kurdistan

- Suwara Ilkhanizada (1937-1976) Among the first poets that composed modern poems in kurdistan

Kurdish poets and writers of the 21st century

- Ekber Rezaî Kelhor (1966-), Contemporary writer, poet from Kermanshah, Iran.

- Besam Mistefa (1977-),Contemporary translator, writer and poet from Khamishly, Syria.

- Suzan Samancı Diyarbakır, Contemporary Writer and Novelist.

- Sara Omar (1986-), Contemporary author, novelist, poet human rights fighter, first internationally recognized Kurdish female novelist from Kurdistan, Iraq

- Yekta Uzunoglu (1953-) Contemporary translator, writer and novelist from Farqin ,Turkey

- Bachtyar Ali (1960-) Novelist from Slemani, Iraqi Kurdistan

References

-

- A Kurdish grammar: descriptive analysis of the Kurdish of Sulaimaniya, Iraq By Ernest Nasseph McCarus, American council of learned societies, 1958, The University of Michigan, page 6

- Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 2 By University of London School of Oriental and African Studies, JSTOR, 1964, page 507

- "The Kurdish Language and Literature". Institutkurde.org. Retrieved 2013-09-02.

- http://andaryari.blogspot.co.uk/2014/01/blog-post.html

- Muhammad Bahadin Sahib, Elder Shalyar the Zoroastrian, Zhian Publications Sulaimaniyah, 2013

- "Hurmizgan Explained". Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- "Binüçyüz Yıl Evvel Yazılmış Kürçe Helbest". Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-13.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- J. N. Postgate, Languages of Iraq, ancient and modern, British School of Archaeology in Iraq, [Iraq]: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 2007, p. 138.

- Uzunoglu, Yekta (1985). "1985 - bi kurdî binivîsîne Hey lê". Yekta Uzunoglu. ku. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- YAZIDIS i. GENERAL at Encyclopædia Iranica

- Kreyenbroek, Philip g. "KURDISH WRITTEN LITERATURE". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- Uzunoglu, Yekta (1996). "1985 - bi kurdî binivîsîne Hey lê". Yekta Uzunoglu (in Kurdish). Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- Khazanedar, Maroof (2002), The history of Kurdish literature, Aras, Erbil.

- Sajjadi Ala'edin (1951), The history of Kurdish literature, Ma'aref, Baghdad.

- "NALÎ: Encyclopedia Iranica".

- "Gurani: Iranica Encyclopedia".

- "Kurdish Institute Of Brussel - Enstituya Kurdî Ya Bruskelê - Instituut Kurde De Bruxelles - Koerdisch Instuut Te Brussel". Kurdishinstitute.be. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved 2013-09-02.

.jpg.webp)