James H. Elmsley

James Harold Elmsley, CB, CMG, DSO (October 13, 1878–January 3, 1954) was a Canadian Major-General who served with the Royal Canadian Dragoons in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War. Later in the war, he would command the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade, as well as the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force during the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War.

James Harold Elmsley | |

|---|---|

Elmsley as a Major (1909) | |

| Born | October 13, 1878 Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | January 3, 1954 (aged 75)[1] Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Canadian |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1897-1929 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit | |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

|

Early life

Elmsley was born in Toronto in 1878, and was the great-grandson of John Elmsley, who had been in turn Chief Justice of Upper Canada during 1796–1802 and then Chief Justice of Lower Canada in 1802–1805.[2] He received his education first in Toronto, followed by time spent at Cardinal Newman’s College in Birmingham, England, and The Oratory School at Edgbaston.[2] He showed an interest in horses from an early age, and, upon returning to Toronto, he won prizes in the saddle class at the Toronto Exhibition in 1899.[3]

Military career

Second Boer War

Elmsley joined the Canadian Militia as a boy, and was commissioned as a provisional 2nd Lieutenant in the Governor General's Body Guard, transferring shortly thereafter to the Royal Canadian Dragoons.[4][2] He fought in the Second Boer War with the Canadian Mounted Rifles,[5] and was aide-de-camp to MGen Sir Edward Hutton of the 1st Mounted Infantry Brigade.[2]

He became a 1st Lieutenant in 1898,[2] and fought in several campaigns. He was wounded in the heart during the Battle of Leliefontein, where a friend took him promptly to the first aid station at which he subsequently survived.[2] He was invalided home to Canada in 1900, but returned to South Africa for a second tour of duty in 1902, returning to Canada later that year.[6] In his service there, he was awarded the following decorations:

| Queen's South Africa Medal (5 clasps) | 1900 | |

| King's South Africa Medal (2 clasps) | 1902 |

Between the wars

After returning home, Elmsley was named as aide-de-camp to then Lieutenant Governor of Ontario Sir Oliver Mowat,[3] and soon became a member of the Toronto Hunt and Polo Club (gaining a reputation as an avid polo player) and the Toronto Club.[3] He married Athol Boulton in 1908.[3][7]

Elmsley remained with the Dragoons,[3] being promoted to Captain in 1905 and Major in 1907.[2] He also served with the British Army in India in 1906,[3][6] and attended the Staff College, Camberley in 1913.[6]

Canadian Expeditionary Force

By 1914, Elmsley was the second in command of the Dragoons,[6] which departed for the United Kingdom in October of that year as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.[2] They embarked for France in May 1917.[2] He was transferred to the staff of the 1st Canadian Division in 1915, later becoming Brigade Major of the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade. He then became the commanding officer of Canadian Corps Cavalry Regiment in 1916, and shortly thereafter returned to 8th CIB as its CO.[6] Arthur Currie, who considered Elmsley to be "one of the most valuable officers I have in the Corps,"[8] relieved him of his command in April 1918, because he was physically worn out at that time,[9] and a Medical Board granted extended leave for him to rest in England.[8] This was more than likely due to the stress from serving under J.E.B. Seely who was replaced the following month,[10] but the Board also noted that his medical history concerning nervous symptoms actually extended back to his South Africa service in 1900.[11]

In addition to being mentioned in dispatches five times,[2] he earned the following decorations:

| Companion of the Order of the Bath | 1918[12] | |

| Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George | 1917[13] | |

| Companion of the Distinguished Service Order | 1916[14] | |

| Croix de guerre (Belgium) | 1918[15] |

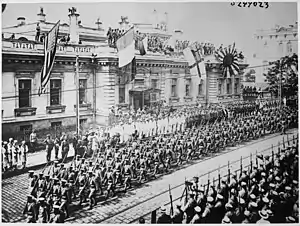

Allied intervention in Siberia

Elmsley was later found by a Medical Board to be once more fit for service,[16] and was appointed to command the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force in August 1918,[17] and the force arrived in Vladivostok two weeks before Armistice was declared in Europe.[18] The various Allied forces did not function well together, because of the underlying chaos and suspicion.[18] In a letter to Minister of Militia and Defence Sydney Mewburn, he gave a description of the situation:

The general situation here is an extraordinary one—at first glance one assumes that everyone distrusts everyone else—the Japs being distrusted more than anyone else. Americans and Japs don't hit it off. The French keep a very close eye on the British, and the Russians as a whole appear to be indifferent of their country's needs, so long as they can keep their women, have their vodka, and play cards all night until daylight. The Czechs appear to be the only honest and conscientious party among the Allies.[19]

The greatest friction he experienced was with MGen Sir Alfred Knox, the head of the British Military Mission.[18] This was despite instructions that placed Elmsley in charge of all British forces in Siberia,[20] under the command of Otani Kikuzo, the commanding officer of all Allied forces in the Russian Maritime Provinces,[21][22] while Knox was only in the role of liaison officer.[23] Elmsley's instructions required him to "keep in touch with [Knox]," while "in political matters you will keep in touch with Sir Charles Elliott [sic]."[24][lower-alpha 1]

The tension between Elmsley and Knox became so great that Elmsley felt compelled to express his views directly to the War Office, thereby bypassing Prime Minister Robert Borden, in which he declared that he would side with the American Expeditionary Force if conflict broke out between them and the Imperial Japanese Army.[25] Borden seized upon this to demand that the Canadian contingent return home, and he received Lloyd George's support in bringing it about.[26]

During the Force's time there, Elmsley felt that his instructions essentially constrained his authority to act by holding his troops in Vladivostok,[27] thus leaving his soldiers generally available only for sentry duty and administrative tasks.[28] On several occasions, he did allow missions to take place for guards on supply trains, as well as a party of 55 men to be sent to Omsk to act as headquarters staff to two British battalions stationed there.[28][29] The only potential military action the Canadians faced was in April 1919, when a company was sent from the 259th Battalion to rescue some Russians loyal to Alexander Kolchak that were being threatened by Bolsheviks at Shkotovo.[28] This had been done under Otani's orders, which conflicted with Ottawa's previous instructions.[30] The Canadian forces were withdrawn from Siberia later that month,[31] followed by the British forces that summer.[28]

He was awarded the following decorations for his service there:

| Croix de guerre (Czechoslovakia) | 1920[32] | |

| Order of the Sacred Treasure, 2nd Class (Japan) | 1921[33] |

Postwar

Elmsley was Adjutant General of the Canadian Militia during the period 1920–1922,[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] afterwards commanding various military districts,[2] and retired with pension in November 1929.[2] He died in Toronto in January 1954.

Further reading

- Beattie, Steuart (1957). Canadian Intervention in Russia, 1918-1919 (MA). McGill University.

- Smith, Gaddis (1959). "Canada and the Siberian Intervention, 1918–1919". The American Historical Review. 64 (4): 866–877. doi:10.2307/1905120. JSTOR 1905120.

- Murby, Robert Neil (1969). Canada's Siberian policy 1918-1919 (MA). University of British Columbia. hdl:2429/35703.

- Brennan, Patrick H. (2002). "Byng's and Currie's Commanders: A Still Untold Story of the Canadian Corps". Canadian Military History. 11 (2): 5–16.

- Moffat, Ian C.D. (2007). "Forgotten Battlefields - Canadians in Siberia 1918-1919" (PDF). Canadian Military Journal. 8 (3): 73–83.

- Brennan, Patrick H. (2009). ""Completely Worn Out by Service in France": Combat Stress and Breakdown among Senior Officers in the Canadian Corps". Canadian Military History. 18 (2): 5–14.

Notes

- In addition to being British Ambassador to Japan, Eliot was also the British High Commissioner in Siberia.[24]

- first year per "Appointments, Promotions and Retirements". Canada Gazette. 54 (18): 1645. October 30, 1920.

- succeeded by Sir Edward Morrison in 1922[34]

References

- "J.H. Elmsley". findagrave.com.

- Snider, Sam (1987). "Elmsley,Major-General James Harold. C.B., C.M.G., D.S.O.". The Journal of the Orders and Medals Research Society. 26 (4): 238–239. ISSN 0308-8995.

- Rose, George Maclean (1909). "Major James Harold Elmsley". Lovers of the Horse. Toronto: The Hunter, Rose Company, Ltd. pp. 149–150.

- "Military General Orders". Canada Gazette. 32 (1): 7. July 2, 1898.

- The 2nd Regiment Canadian Mounted Rifles and 10th Canadian Field Hospital A.M.C. Ottawa: King's Printer. 1902.

- "Major-General James Harold ELMSLEY, CB, CMG, DSO" (PDF). World War I Canadian Generals. p. 42.

- "James Harold Elmsley and Athol Florence Boulton". familysearch.org. April 28, 1908. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- Brennan 2009, p. 9.

- Brennan 2002, p. 7, p. 15 at fn. 15.

- Brennan 2002, p. 16 at fn. 30.

- Brennan, Patrick (2009). "'Completely Worn Out by Service in France': Combat Stress and Breakdown among Senior Officers in the Canadian Corps". Canadian Military History. 18 (2): 5–10.

- "Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood". The London Gazette (2nd supplement). No. 30716. 31 May 1918. p. 6452.

- "Chancery of the Order of St Michael and St George". The Edinburgh Gazette (1st supplement). No. 13099. 4 June 1917. p. 1051.

- "War Office". The London Gazette (1st supplement). No. 29608. 2 June 1916. p. 5570.

- "Decorations conferred by His Majesty the King of the Belgians". The London Gazette (5th supplement). No. 30792. 9 July 1918. p. 8186.

- Brennan 2009, p. 11.

- Smith 1959, p. 871.

- Smith 1959, p. 872.

- Beattie 1957, p. 119.

- Murby 1969, pp. 44-45.

- Murby 1969, p. 17.

- Minohara, Toshihiro; Hon, Tze-Ki; Dawley, Evan N., eds. (2015). The Decade of the Great War: Japan and the Wider World in the 1910s. Leiden: Brill. p. 53. ISBN 978-90-04-27427-3.

- Moffat 2007, p. 79.

- Murby 1969, p. 18.

- Smith 1959, p. 874.

- Smith 1959, pp. 874-875.

- Murby 1969, p. 25.

- Moffat 2007, p. 82.

- Murby 1969, p. 31.

- Murby 1969, p. 41.

- "Elmsley and Men return to Canada". The Toronto World. June 21, 1919. p. 1.

- "Decorations conferred by the Government of the Czecho-Slovak Republic". The Edinburgh Gazette. No. 13647. 2 November 1920. p. 2323.

- "Decorations conferred by His Majesty the Emperor of Japan". The London Gazette (4th supplement). No. 32428. 19 August 1921. p. 6569.

- Rawling, William (2005). "Morrison, Sir Edward Whipple Bancroft". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. XV (1921–1930) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Search Results: South African War, 1899-1902 – Service Files, Medals and Land Applications". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- "Service Record". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- "Brigadier General James Harold Elmsley". cwgp.uvic.ca. Canadian Great War Project, University of Victoria. 2009.