James Squire

James Squire, alternatively known as James Squires, (18 December 1754 – 16 May 1822) was a First Fleet convict transported to Australia..[1][2] Squire is credited with the first successful cultivation of hops in Australia around the start of the 19th century. First officially brewing beer in Australia in 1790; James later founded Australia's first commercial brewery making beer using barley and hops in 1798, although John Boston appears to have opened a brewery making a form of corn beer two years earlier.[3]

James Squire | |

|---|---|

| Born | 18 December 1754 Kingston upon Thames, England |

| Died | 16 May 1822 (aged 67) Kissing Point, New South Wales, Australia |

| Other names | James Squires |

| Occupation | Primarily a brewer, but also:

|

| Spouse(s) | Martha Quinton. Left in England when Squire was transported. |

| Partner(s) |

|

| Children | 11 |

| Signature | |

Squire was convicted of stealing in 1785 and was transported to Australia as a convict on the First Fleet in 1788. Squire ran a number of successful ventures during his life, including a farm, a popular tavern called The Malting Shovel, a bakery, a butcher shop and a credit union. He also became a town constable in the Eastern Farms district of Sydney. As a testament to the rise of position in society (from shame to fame), his death in 1822 was marked with the biggest funeral ever held in the colony.

Early years

Birth

James Squire was baptised on 18 December 1754 in Kingston upon Thames. Squire's parents were Romanies (Romanichal),[4] Timothy Squires and Mary Wells, who were married on 8 December 1752 in West Molesey, Surrey. Their families had been embroiled in a dramatic incident (the Canning affair) which polarised England in 1754, the year of Squire's birth.[5][lower-alpha 1]

Early crimes

In 1774, when Squire fled a ransacked house, he ran straight into several members of the local constabulary and was arrested for highway robbery. This was actually a lucky break. By escaping through the front door, which opened onto the highway, he avoided a more serious charge of stealing. Although Squire was sentenced to be transported to America for 7 years, he elected to serve in the army and returned to Kingston as a free man within 4 years.[6] He then managed a hotel in Heathen Street, Kingston. This hotel was a popular haunt for highway robbers and smugglers.

His next attempt at a life of crime was similarly unsuccessful. Squire stole five hens and four cocks and diverse other goods and chattels from John Stacey's yard, just when the British Government needed people for the transported convict program. On 11 April 1785, he was sentenced to join the First Fleet at the General Sessions of the Peace for the Town & Hundred of Kingston upon Thames, England.[6] Squire was sentenced to 7 years' transportation, beyond the seas.

Wife, mistresses and children

In 1776 Squire married his local sweetheart, Martha Quinton. Martha was baptised on 15 November 1754 in Bishop's Waltham, Hampshire, England. Her parents were John Quinton and Elizabeth Harris. Martha bore 3 children to James—John (born 1778 in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey and baptised on 16 August 1778), Sarah (born 1780 in Kingston upon Thames and baptised on 23 August 1780[7]) and James (born 2 May 1783 in Kingston upon Thames and baptised on 2 May 1783[7]). When James was convicted and transported to Australia as a convict, it was very rare for convicts or their family to attain permission, or even afford to join them in their exile, so Martha and his children were left in England alone.

While Squire was separated from his wife and family he met Mary Spencer. Mary was born in 1768 in the town of Formby. She was tried in Wigan on 9 October 1786 for with theft at Crosby of one cotton and one black silk handkerchief, a green quilted tammy (glazed material partly wool) petticoat and a black silk cloak, of unknown value. She was sentenced to transportation for 5 years,[lower-alpha 2] and left England on the Prince of Wales aged about 19 at that time (May 1787). She had no occupation recorded.[7]

Mary gave birth to a son, who was named Francis (born and baptised on 1 August 1790 on Norfolk Island[7]). He died on 20 September 1851 in Melbourne). Unable to care for Francis, James enrolled him in the British Army at just 15 months of age. Francis was enlisted into the NSW Corps as a drummer, starting on the payroll on his 7th birthday.

In 1791 James began a relationship with Elizabeth Mason (born 1759 in London, baptised 20 February 1759 in London, died 10 June 1809 in Sydney), who was his live-in convict servant.[8] James and Elizabeth had 7 children together—Priscilla (born 29 May 1792 in Sydney, died 1862 in Ryde[7]), Martha (born 2 March 1794 at Kissing Point, died 15 November 1814 at Concord, Sydney[7]), Sarah (born 7 August 1795 at Kissing Point, baptised 13 March 1796 at St. John's C of E, Parramatta, died 23 May 1877 at Kingston, now a part of Newtown[7]), James (born 16 November 1797 at Kissing Point, died 3 July 1826 at Kissing Point and is buried in Devonshire Street Cemetery[7]), Timothy (born 1799 at Kissing Point, died 7 October 1814), Elizabeth (born 16 May 1800 at Kissing Point, died 12 May 1830 in Sydney[7]) and Mary Ann (born 1 August 1804 in Kissing Point, died 1 September 1850 in Ryde[7]).

James then maintained an affair over a number of years with his live-in housekeeper Lucy Harding (aka Lucy Vaughan-Harding). He eventually moved into her private residence on Castlereagh Street, Sydney in 1816.

Convict years

First Fleet

In 1787, James was released from Southwark gaol to voyage to the British penal colony in Australia in April 1787.[6][9] The document was signed by Evan Nepean on 10 March 1787. Though James began his journey on the Friendship, he transferred himself to the Charlotte in a reshuffle of the women passengers.[10] On 18 January 1788, the First Fleet arrived at Botany Bay, Australia. The openness of this bay, and the dampness of the soil, by which the people would probably be rendered unhealthy, had already determined the Governor to seek another situation. He resolved, therefore, to examine Port Jackson, a bay mentioned by Captain James Cook as immediately to the north of this. There he hoped to find, not only a better harbour, but a fitter place for the establishment of his new government.[11] The first fleet then moved to Port Jackson by 26 January.

In Sydney town

On 5 March 1789, Squire gave evidence on the theft by two fellow convicts of six cabbages. The thieves received 50 lashes each.[12] He was then arraigned before the magistrate, charged with stealing 'medicines' from the hospital stores where he worked at Port Jackson. These medicines were, in fact, one pound of pepper (or paper) and horehound (a herb that imitates the tangy flavour of hops), belonging to surgeon John White. Though Squire claimed the stolen horehound was for his pregnant girlfriend, he later revealed at the Bigge inquiry that he began brewing beer on his arrival to Australia, which he sold for 4d per quart. Indeed, he was brewing beer for the personal consumption of Lieutenant Francis Grose and William Paterson over that time. Perhaps that explains Squire's possibly lenient sentence when petty theft was often severely punished. His sentence of 14 November 1789 read:

"one hundred and fifty (lashes of the whip) now, and the remainder when able to bear it".

19 August 1791, Squire and another man were fined £5 each for buying the necessaries of a private. They both protested that they did not know it was a crime.

Post convict years

Land grant

Somewhere between 1790 and 1792 James Squire's sentence had expired and he was now a free man[14] and he was able to start his life over again. On emancipation James was granted 30 acres (0.12 km2) at Eastern Farms (Kissing Point) on 22 July 1795,[15] and he noticed other emancipists had not claimed the nearby land. Displaying his resourcefulness, James marched them into the Colonial Secretary's office (position held by David Collins) to claim their land grants, and then purchased each property for one shilling.

James was an extremely enterprising man and by mid-1800 he had ten sheep, 18 pigs and 35 goats. 5 acres (0.02 km2) were sown in wheat & another 45 acres (0.18 km2) ready for planting maize and barley. Two years later he owned 291 acres (1.18 km2) with 120 acres (0.49 km2) cleared and 28 acres (0.11 km2) in grain. His household was composed of him and Elizabeth Mason, six children, four free men and two government servants and was self-supporting.[5]

On 3 January 1813, an Aboriginal named Bennelong was buried on the grounds of Squire's property, where he had often wandered. James had erected a plaque to commemorate his dear friend.

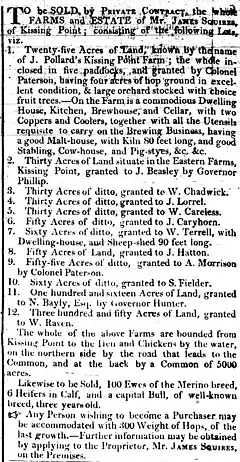

On 3 May 1817, James advertised his estate for sale in the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser.[13] This may have been instigated because he had moved in with his mistress, Lucy Harding, in Sydney. Evidence shows that the estate did not sell as James was the name of the licensee until at least 1822.

Hops and brewing

James stated at the Bigge inquiry into New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land in 1820 that he had been brewing for 30 years and that he made it from hops he got from the Daedalus.[16][2] This statement highlights the fact that James had been brewing beer since 1790, which makes this the first evidence of brewing beer with hops in Australia.

1802 saw the revelation that the British Army was trafficking rum. This created an uproar in the fledgling colony and Governor King was gravely concerned about the corruption spread by rum, so he began to officially endorse the brewing of beer. English hops and brewing equipment were regularly transported on convict ships at the government's expense; in fact, part of HMS Porpoise's botanical cargo was hops.[17][18][19][20] There were 3 parties that were the most likely recipients of the shipment of hops, those being:

- The Government Gardens;

- John Boston (who was a potential rival for Australia's first brewer); and

- James Squire.

It is unclear what became of the hops on HMS Porpoise, as there is no evidence of them being propagated within the first two years of its arrival in Sydney, on 6 November 1800.[21][22] Then in 1806, after 3 seasons of toil, James successfully cultivated the first Australian hops.

On 11 March 1806 James Squire attended Government House with two vines of hops taken from his own grounds. On a vine from a last year's cutting were numbers of a very fine bunches; and upon a two-year-old cutting the clusters, mostly ripe, were innumerable, in weight supposed to yield at least a pound and a half, and of most exquisite flavour. Governor King was so pleased with the flavour and quality that he:

"directed a cow to be given to Mr Squire from the Government herd".[23]

By 1806, the Squire estate now stretched across approximately 881 acres (3.57 km2), from the current Gladesville Bridge to the Ryde Rail Bridge and from the harbour to north of Victoria Road.

It is most likely that James' hop growing knowledge broadened with the publishing of an article, in the Sydney Gazette called, "Hop Plantation. Culture of Hops in Great Britain". This article ran over 6 months from 20 January until 9 June 1805 and went into great detail as to the process of cultivation of hops.[24]

As the 19th century gained momentum, Squire's enterprises did likewise. After the Rum Rebellion in 1808, James began work as a baker (James had a bakery in Kent Street), and he also often supplied meat to the colony, not to mention his farming duties. He then worked in a credit union style of banking and was widely known for his fair play as a lender and a philanthropist to his poorer neighbours. James was nicknamed the 'Patriarch of Kissing Point'. Colonial artist Joseph Lycett explained:

"Had he not been so generous, James Squire would have been a much wealthier man".

Joseph Lycett also stated that James was:

"Universally respected for his amiable and useful qualities as a member of the lower class of settlers... his name will long be pronounced with veneration by the grateful objects of his liberality".

Despite his previous convict status, James also became a resident district constable.[25] This was due to the number of trespassers on his property and theft of his belongings. The Sydney Gazette is riddled with articles submitted by James, warning others of trespassers and thefts. For example, in the Sydney Gazette on 3 July 1803 James submitted a notice of theft of a boat.

The Malting Shovel

James opened "The Malting Shovel" Tavern on the shores of Parramatta River, in the Eastern Farm district of Kissing Point which is almost halfway between Sydney town and Parramatta. It was the ideal location to entice thirsty passengers from vessels along this busy thoroughfare. Surviving records located in the State Records Authority of New South Wales show that, on 19 September 1798, there was a general meeting held at the Judge Advocates office in the presence of Judge Advocate William Balmain. At this meeting, James (among others, including Simeon Lord) obtained the judge's permission to be licensed for the sale of spirituous liquors at The Malting Shovel. This license cost him a princely sum of £5.[26] The licence was renewed for a further £5 in September 1799. Simeon Lord countersigned as surety.[27] Licences to brew or sell liquor were required to be renewed every year. Unfortunately a lot of this information is missing, but the Sydney Gazette and the State Records Authority of New South Wales fill in a number of gaps with evidence of licence renewals on the following dates:

Death of James Squire

James Squire died on 16 May 1822. The article from the Sydney Gazette stated:

Deaths: – On Thursday evening last, at Kissing Point, after an illness of about 3 months, Mr James Squire, in his 68th year. As one of the primary inhabitants of the Colony, having come hither in the first fleet in 1788, none ever more exerted himself for the benefits of the inhabitants than the deceased. He was the first that brought Hops to any perfection and hence was enabled to brew beer of an excellent quality. "Squire's Beer" was well known. He might for long residence, be styled the Patriarch of Kissing Point; as he had lived, where he died, 26 years. The "OLD HANDS",[lower-alpha 3] by the frequent visitation of death, are becoming thinned in their ranks; this should lead to reflection, for the day will soon arrive when even those, now living, shall cease to say, "I came in the first fleet."[31]

His death was marked with the biggest funeral ever held in the colony. He was buried at the Devonshire Street Cemetery, and his remains and headstone were later moved to Botany Cemetery when Central station was built. The headstone is now too worn to be identified.[32] The headstone inscription is believed to have the following epitaph:

"In Sacred Respect to the Loving Remains of Mr. Jas. Squire, late of Kissing Point who departed this Life 16 May 1822 at the age of 67 years. He arrived in the colony in the First Fleet and by Integrity and Industry acquired and maintained an unsullied reputation. Under his care the HOP PLANT was first Cultivated in this Settlement and the first BREWERY erected which Progressively matured to Perfection. As a Father, Friend and Christian he Lived Respected and Died Lamented.[33]

Legacy

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

James Squire's last will and testament was dated 6 April 1822.

From 1823, Squire's brewery continued to successfully operate under control of his son James, producing about 100,000 gallons a year, until his death in 1826. James Squire's daughter, Mary Ann. married Thomas Charles Farnell of Kissing Point[34] on 30 March 1824. On 25 June 1825, Mary gave birth to James Squire Farnell.[35] In 1828 the brewery was briefly re-opened by his daughter's husband, Thomas Farnell,[36][37] until his ill-health forced the brewery to close in 1834. In 1877, James' grandson, James Squire Farnell, became the eighth Australian Premier of New South Wales.[35]

In 1999 Lion Nathan renamed the previously-purchased Hahn Brewery as the Malt Shovel Brewery, releasing a line of James Squire beers in honour of Australia's first commercial brewer.[38]

Gallery

Photo of a plaque at Kissing Point commemorating James Squire and the location of his Brewery.

Photo of a plaque at Kissing Point commemorating James Squire and the location of his Brewery. Photo of a plaque at Kissing Point commemorating William Careless and James Weavers. Of note is the information pertaining to James Squire and the location of his property.

Photo of a plaque at Kissing Point commemorating William Careless and James Weavers. Of note is the information pertaining to James Squire and the location of his property.

Notes

- This is contentious - The Canning affair trial was held in 1753 & 1754 and Mary Squire was stated to be between 60 & 80 Years old with 3 adult children. As James birth date is supposed to be 18 December 1754, it would be impossible for him to be the child of this Mary Squire.

- The 5 year term was a clerical error in Mary Spencer's favour. It should have been 7 years.

- Term for convicts of the first fleet, generally used by the convicts themselves.

References

- Walsh, G P. "Squire, James (1754–1822)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- HMS Daedalus first arrived in Sydney in 1793

- Iltis, Judith. "Boston, John (? – 1804)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- Acton, T A & Mundy, G (1997). Romani Culture and Gypsy Identity. University of Hertfordshire Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780900458767.

- "James Squire". North Coast Chapter, Fellowship of First Fleeters. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- "James Squire – the remarkable life of the father of Australian brewing". Archived from the original on 23 July 2003.

- "Group Sheet for James Squire". North Coast Chapter of the, Fellowship of First Fleeters. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- State Records Authority of New South Wales List of persons employing female servants, dated 7 October 1798

- "Letter of transportation: James Squire and James Bloodworth" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2012 – via Kingston upon Thames Council.

"Transcript of letter of transportation: James Squire and James Bloodworth". Kingston upon Thames Council. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. - Watkin Tench's Journal. A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson by Watkin Tench. Later published as the book '1788'

- The Voyage Of Governor Phillip To Botany Bay by Arthur Phillip

- From the Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society Vol.82 part 2, pp. 153–167, by David Hughes. Titled: Australia's first brewer.

- "Classified Advertising". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 3 May 1817. p. 4. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via Trove.

- Entry for 22 July 1795 in the return of Grants of Land, 1792—95, ML, Bonwick Transcripts, Box 88, p. 13, says Squire was a 'Convict whose sentence is expired'.

- Colonial Secretary Index, 1788–1825 Archived 18 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, On list of all grants and leases of land registered in the Colonial Secretary's Office (Fiche 3267; 9/2731 p.54)

- From the Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society Vol.82 part 2, by David Hughes. Titled: Australia's first brewer.

- Correspondence concerning the outfitting and equipping of HMS Porpoise for a voyage to New South Wales, 1797–1801

- Plants List on board HMS Porpoise

- A List of the Culinary & Medicinal Plants Vineyard Vines Fruits &c &c Planted in 18 Boxes & now Remaining at the Royal Gardens at Kew...', 11 October 1798

- A plan of where the seed boxes were located on the Porpoise

- "Convictions Australian Shipping". Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- Correspondence concerning the outfitting and equipping of HMS Porpoise for a voyage to New South Wales, 1797–1801. State Library of New South Wales

- "Sydney". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 16 March 1806. p. 2. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via Trove.

- "Hop Plantation. Culture of Hops in Great Britain". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 20 January 1805. p. 3. 3 February 1805, p. 3. 10 February, p. 3. 17 February 1805, p. 3. 17 March 1805, p. 3. 24 March 1805, p. 2. 19 May 1805, p. 3. 26 May 1805, p. 3. 2 June 1805, p. 3. and "9 June 1805". p. 2. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via Trove.

- "Sydney". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 20 January 1805. p. 2. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via Trove.

- State Records Authority of New South Wales. Dated: 19 September 1798 – Page:92 – Bundle:15 – Reel:655 – On a list of licences granted to sell spirituous liquors

- State Records Authority of New South Wales. Dated: 14 September 1799 – Page:115 – Bundle:46 – Reel:655 – On a list of people granted licences to sell spirituous liquors

- The Sydney Gazette

- Colonial Secretary Index, 1788–1825 Archived 18 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, (Reel 6038; SZ758 p.184)

- Colonial Secretary Index, 1788–1825 Archived 18 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine Letter to Wentworth re Squire's application for a brewing licence (Reel 6004; 4/3494 p.366)

- "Death: Mr James Squire". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 24 May 1822. p. 2. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via Trove.

- Researched by Jeremy Ohlback From the Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society Vol.82 part 2, pp. 153–167, by David Hughes. Titled: Australia's first brewer.

- "Stories from the Fellowship of the First Fleeters". Archived from the original on 12 May 2006. Retrieved 9 June 2007.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Colonial Secretary Index, 1788–1825 Archived 18 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, (Reel 6028; 2/8305 pp.59–62)

- Goodin, V W E. "Farnell, James Squire (1825–1888)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 12 August 2013 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- "Squires old established brewery at Kissing Point, revived". The Monitor (Sydney). 29 March 1828. p. 2. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via Trove.

- "Licensed publicans in Parramatta". The Australian. 10 March 1829. p. 3. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via Trove.

- Lion Nathan's History. Archived 5 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine