John Mitchel

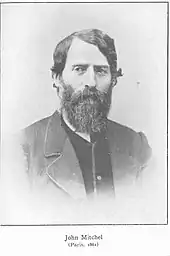

John Mitchel (Irish: Seán Mistéal; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish nationalist activist, author, and political journalist. In the Famine years of the 1840s he was a leading writer for the Nation produced by the Young Ireland group and their splinter from Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association, the Irish Confederation. As editor of his own paper, the United Irishman, in 1848 Mitchel was sentenced to 14-years penal transportation, penalty for his advocacy of James Fintan Lalor's programme of co-ordinated resistance to exactions of landlords and to the continued shipment of harvests to England. Controversially for a republican tradition that has viewed Mitchel, in the words of Pádraic Pearse, as a "fierce" and "sublime" apostle of Irish nationalism,[1] in the American exile into which he escaped in 1853, Mitchel was an uncompromising pro-slavery partisan of the Southern secessionist cause. In the year he died, 1875, Mitchel was twice elected to British Parliament from Tipperary on a platform of Irish Home Rule, tenant rights and free education, and twice denied his seat as a convicted felon.

John Mitchel | |

|---|---|

.JPG.webp) | |

| Born | 3 November 1815 Camnish, County Londonderry, Ireland |

| Died | 20 March 1875 (aged 59) Newry, Ireland |

| Occupation | Journalist, author, soldier |

| Known for | Irish republican and member of the Young Irelanders |

Early life

.jpeg.webp)

John Mitchel was born at Camnish near Dungiven in then County Londonderry, in the province of Ulster. His father, Rev. John Mitchel, was a Non-subscribing Presbyterian minister of Unitarian sympathies, and his mother was Mary (née Haslett) from Maghera. From 1823 until his death in 1840, John Sr. was minister in Newry, County Down. In Newry, Mitchel attended a school kept by a Dr Henderson whose encouragement and support laid the foundation for classical scholarship that at age 15 gained him entry to Trinity College, Dublin. After taking his degree at age 19 he worked briefly as a bank clerk in Derry, before entering legal practice in the office of a Newry solicitor, a friend of his father.[2]

In the spring of 1836 Mitchel met Jane "Jenny" Verner, the only daughter of Captain James Verner. Despite family opposition, and after two elopements, they became engaged in the autumn and were married in February 1837.

The couple's first child, John, was born in January the following year. Their second, James, (who was to be the father of the New York Mayor John Purroy Mitchel) was born in February 1840. Two further children were born, Henrietta in October 1842, and William in May 1844, in Banbridge, County Down, where as a qualified attorney Mitchel opened a new office for the Newry legal practice.[2]

Early politics

One of Mitchel's first steps into Irish politics was to face down threats of Orange retaliation by helping arrange, in September 1839, a public dinner in Newry for Daniel O'Connell, the leader of the campaign to repeal the 1800 Acts of Union and restore a reformed Irish Parliament.[3]

Until his marriage, John Mitchel had by and large taken his politics from his father who, according to Mitchel's early biographer William Dillon, had "begun to comprehend the degradation of his countrymen". Soon after the granting of Catholic emancipation in 1829, the O'Connellites challenged the Protestant Ascendancy in Newry by running a Catholic parliamentary candidate. Many members of the Rev. Mitchel's congregation took an active part in the elections on the side of the Ascendancy, and pressed the Rev. Mitchel to do the same. His refusal to do earned him the nickname "Papist Mitchel."[3]

In Banbridge, Mitchel was often employed by the Catholics in the legal proceedings arising from provocative, sometimes violent, Orange incursions into their districts. Seeing how cases were handled by magistrates, who were themselves often Orangemen, enraged Mitchel's sense of justice and spurred his interest in national politics and reform.[3]

In October 1842, his friend John Martin sent Mitchel the first copy of The Nation produced in Dublin by Charles Gavan Duffy, previously editor of the O'Connellite journal, The Vindicator, in Belfast, and by Thomas Osborne Davis, and John Blake Dillon, both like himself Protestants and graduates of Trinity College. "I think The Nation will do very well", he wrote Martin, while at the same time revealing that he knew how the country "ought to take" news that an additional 20,000 British troops were to be deployed to Ireland but would not put it on paper for fear of arrest.[3]

The Nation

Succeeds Thomas Davis

Mitchel began to write for the Nation in February 1843. He co-authored an editorial with Thomas Davis, "the Anti-Irish Catholics", in which he embraced Davis's promotion of the Irish language and of Gaelic tradition as a non-sectarian basis for a common Irish nationality. Mitchel, however, did not share Davis's anti-clericalism, declining to support Davis as he sought to reverse O'Connell's opposition to the government's secular, or as O'Connell proposed "Godless", Colleges Bill.[4]

Mitchel insisted that the government, aware that it would cause dissension, had introduced their bill for non-religious higher education to divide the national movement. But he also argued that religion is integral to education; that "all subjects of human knowledge and speculation (except abstract science)--and history most of all--are necessarily regarded from either a Catholic or a Protestant point of view, and cannot be understood or conceived at all if looked at from either, or from both".[5] For Mitchel a cultural nationalism based on Ireland Gaelic heritage was intended not to displace the two religious traditions but rather serve as common ground between them.[4]

When in September 1845, Davis unexpectedly died of scarlet fever, Duffy asked Mitchel to join the Nation as chief editorial writer. He left his legal practice in Newry, and brought his wife and children to live in Dublin, eventually settling in Rathmines.[6] For the next two years Mitchel wrote both political and historical articles and reviews for The Nation. He reviewed the Speeches of John Philpot Curran, a pamphlet by Isaac Butt on The Protection of Home Industry, The Age of Pitt and Fox, and later on The Poets and Dramatists of Ireland, edited by Denis Florence MacCarthy (4 April 1846); The Industrial History of Free Nations, by Torrens McCullagh, and Father Meehan's The Confederation of Kilkenny (8 August 1846).

Responds to the Famine

On 25 October 1845 Mitchel wrote on "The People's Food", pointing to the failure of the potato crop, and warning landlords that pursuing their tenants for rents would force them to sell their other crops and starve.[7] On 8 November, in an article titled "The Detectives", he wrote, "The people are beginning to fear that the Irish Government is merely a machinery for their destruction; ... that it is unable, or unwilling, to take a single step for the prevention of famine, for the encouragement of manufactures, or providing fields of industry, and is only active in promoting, by high premiums and bounties, the horrible manufacture of crimes!".[8]

On 14 February 1846 Mitchel wrote again of the consequences of previous autumn's potato crop losses, condemning the Government's inadequate response, and questioning whether it recognised that millions of people in Ireland who would soon have nothing to eat.[6] On 28 February, he observed that the Coercion Bill, then going through the House of Lords, was "the only kind of legislation for Ireland that is sure to meet with no obstruction in that House". However they may differ about feeding the Irish people, the one thing all English parties were agreed upon was "the policy of taxing, prosecuting and ruining them."[9]

In an article on "English Rule" on 7 March 1846, Mitchel wrote: "The Irish People are expecting famine day by day... and they ascribe it unanimously, not so much to the rule of heaven as to the greedy and cruel policy of England. ... They behold their own wretched food melting in rottenness off the face of the earth, and they see heavy-laden ships, freighted with the yellow corn their own hands have sown and reaped, spreading all sail for England; they see it and with every grain of that corn goes a heavy curse".[9]

Break with O'Connell

In June 1846 the Whigs, with whom O'Connell had worked against the Conservative ministry of Robert Peel, returned to office under Lord John Russell. Invoking new laissez-faire doctrines "political economy", they immediately set about dismantling Peel's limited, but practical, efforts to provide Ireland food relief.[10] O'Connell was left to plead for his country from the floor of the House of Commons: "She is in your hands—in your power. If you do not save her, she cannot save herself. One-fourth of her population will perish unless Parliament comes to their relief".[11] A broken man, on the advice of his doctors O'Connell took himself to the continent where, on route to Rome, he died in May 1847.

In the months before O'Connell's death, Duffy circulated letters received from James Fintan Lalor in which he argued that independence could be pursued only in a popular struggle for the land. While he proposed that this should begin with a campaign to withhold rent, he suggested more might be implied.[12] Parts of the country were already in a state of semi-insurrection. Tenants conspirators, in tradition of the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen, were attacking process servers, intimidating land agents, and resisting evictions. Lalor advised only against a general uprising: the people, he believed, could not hold their own against the country's English garrison.[13]

The letters made a profound impression on Mitchel. When the London journal the Standard observed that the new Irish railways could be used to transport troops to quickly curb agrarian unrest, Mitchel responded that the tracks could be turned into pikes and trains ambushed. O’Connell publicly distanced himself from The Nation, appearing to some to set Duffy, as the editor, up for prosecution.[14] In the case that followed Mitchel successfully defended Duffy in court.[14] O'Connell and his son John were determined to press the issue. On the threat of their own resignations, they carried a resolution in the Repeal Association declaring that under no circumstances was a nation justified in asserting its liberties by force of arms.[15]

The grouping around the Nation that O'Connell had taken to calling "Young Ireland", a reference to Giuseppe Mazzini's anti-clerical and insurrectionist Young Italy, withdrew from the Repeal Association. In January 1847, they formed themselves anew as the Irish Confederation with, in Michael Doheny words, the "independence of the Irish nation" the objective and "no means to attain that end abjured, save such as were inconsistent with honour, morality and reason".[16] But unable to secure a pronouncement in favour of Lalor's policy, making control of land the issue in a campaign of resistance, Mitchel soon broke with his confederates.

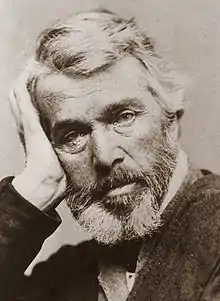

Embraces the illiberalism of Carlyle

Duffy suggests that Mitchel had already been on a path that would see him break not only with O'Connell but also with Duffy himself and other Young Irelanders. Mitchel had fallen under what Duffy viewed as the baneful influence of Thomas Carlyle, the British historian and philosopher notorious for his antipathy toward liberal notions of enlightenment and progress.[17]

In the Nation of 10 January 1846, Mitchel reviewed Carlyle's annotated edition of Oliver Cromwell's correspondence and speeches only two weeks after it had been publicly condemned by O'Connell. Despite Mitchel himself waxing indignant at Cromwell's conduct in Ireland, Carlyle was pleased: he believed Mitchel had conceded Cromwell's essential greatness.[18] Mitchel had just published his own hagiography of the Ulster rebel chieftain Hugh O'Neill, which both Duffy and Davis had found excessively "Carlylean". The book was a success: "an early incursion of Carlylean thought into the romantic construction of the Irish nation that was to dominate militant Irish politics for a century."[19] It embraced Carlyle's view both of "Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History" (1840) and of the importance of racial identities trampled and compromised in the name of "what is called civilisation".[20]

When in May 1846 Mitchel first met Carlyle in a delegation with Duffy in London, he wrote to John Martin describing the Scotsman's presence as "royal, almost Godlike", and did so even while acknowledging Carlyle's unbending unionism. Carlyle compared Irish efforts at repeal to those of "a violent-tempered starved rat, extenuated into frenzy, [to] bar the way of a rhinoceros".[21] In what might have been more galling for Mitchel, Carlyle increasingly was to caricature the Irish in same manner as he did the blacks of the West Indies, former slaves for whom he allowed nothing in extenuation.[22] Like pumpkins in which he describes "blacks sitting up to the ears"[23] Carlyle argued that in Ireland the ready potato crop discouraged labour: the Irish "won't work ... if they have potatoes or other means of existing".[24]

Mitchel's response was not join O'Connell in proclaiming himself "the friend of liberty in every clime, class and color"[25] Rather, it was to insist on a racial distinction between the Irish and the "negro". This Duffy discovered in 1847 when conceding temporary editorship of the Nation to Mitchel he found that he had lent a journal, "recognised throughout the world as the mouthpiece of Irish rights", to "the monstrous task of applauding negro slavery and of denouncing the emancipation of the Jews"<[26][27] (another of O'Connell's liberal causes against which Mitchel stood with Carlyle).

It was not only that Mitchel claimed (as others had done) that Irish cottiers were treated worse than black slaves. Nor was it that Mitchel decried as inopportune O'Connell's harping upon "the vile union" in the United States "of republicanism and slavery".[28][29] Duffy himself was fearful of the impact of O'Connnell's vocal abolitionism upon American support and funding.[30] It was that Mitchel argued (with Carlyle)[31][32] that slavery was "the best state of existence for the negro".[33][34]

Hosted by Mitchel in September 1846 in Dublin, Carlyle recalled "a fine elastic-spirited young fellow, whom I grieved to see rushing to destruction ..., but upon whom all my persuasions were thrown away".[35] Carlyle later said, when Mitchel was on trial, "Irish Mitchel, poor fellow… I told him he would most likely be hanged, but I told him, too, that they could not hang the immortal part of him."[6]

The United Irishman

At the end of 1847 Mitchel resigned his position as leader writer on The Nation. He later explained that he had come to regard as "absolutely necessary a more vigorous policy against the English Government than that which William Smith O'Brien, Charles Gavan Duffy and other Young Ireland leaders were willing to pursue". He "had watched the progress of the famine policy of the Government, and could see nothing in it but a machinery, deliberately devised, and skilfully worked, for the entire subjugation of the island—the slaughter of portion of the people, and the pauperization of the rest," and he had therefore "come to the conclusion that the whole system ought to be met with resistance at every point."[2]

While he would admit no principle that distinguished his position from the "conspirators of Ninety-Eight" (the original United Irishmen), Mitchel emphasised that he was not recommending "an immediate insurrection": in the "present broken and divided condition" of the country "the people would be butchered". With Finton Lalor he urged "passive resistance": the people should "obstruct and render impossible the transport and shipment of Irish provisions" and by intimidation in necessary suppress bidding for grain or cattle if brought "to auction under distress", a method that had demonstrated its effectiveness in the Tithe War. Such actions would be illegal, but such was his opposition to British rule that in Mitchel's view, no opinion in Ireland was "worth a farthing which is not illegal".[2]

The first number of Mitchel's own paper, The United Irishman, appeared on 12 February 1848. The Prospectus announced that as editor Mitchel would be "aided by Thomas Devin Reilly, John Martin of Loughorne and other competent contributors" who were likewise convinced that "Ireland really and truly wants to be freed from English dominion." Under the masthead Mitchel ran the words of Wolfe Tone: "Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they must fall; we can support ourselves by the aid of that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property."[36]

The United Irishman declared as its doctrine

... that the Irish people had a distinct and indefeasible right to their country, and to all the moral and material wealth and resources thereof, ... as a distinct Sovereign State; ... that the life of one peasant was as precious as the life of one nobleman or gentleman; that the property of the farmers and labourers of Ireland was as sacred as the property of all the noblemen and gentlemen in Ireland, and also immeasurably more valuable; [and] that every freeman, and every man who desired to become free, ought to have arms, and to practise the use of them".[6]

In the first editorial, addressed to "The Right Hon. the Earl of Clarendon, Englishman, calling himself Her Majesty's Lord Lieutenant – General and General Governor of Ireland," Mitchel stated that the purpose of the journal was to resume the struggle which had been waged by Tone and Emmet, the Holy War to sweep this Island clear of the English name and nation." Lord Clarendon was also addressed as "Her Majesty's Executioner-General and General Butcher of Ireland".[37][38]

Commenting on this first edition of The United Irishman, Lord Stanley in the House of Lords, on 24 February 1848, maintained that the paper pursued "the purpose of exciting sedition and rebellion among her Majesty's subjects in Ireland..., and to promote civil war for the purpose of exterminating every Englishman in Ireland.” He allowed that the publishers were “honest” men: “they are not the kind of men who make their patriotism the means of barter for place or pension. They are not to be bought off by the Government of the day for a colonial place, or by a snug situation in the customs or excise. No; they honestly repudiate this course; they are rebels at heart, and they are rebels avowed, who are in earnest in what they say and propose to do”.[39]

Only 16 editions of The United Irishman had been produced when Mitchel was arrested, and the paper suppressed. Mitchel concluded his last article in The United Irishman, from Newgate prison, entitled "A Letter to Farmers",

[My] gallant Confederates ... have marched past my prison windows to let me know that there are ten thousand fighting men in Dublin— 'felons' in heart and soul. I thank God for it. The game is afoot, at last. The liberty of Ireland may come sooner or come later, by peaceful negotiation or bloody conflict— but it is sure; and wherever between the poles I may chance to be, I will hear the crash of the down fall of the thrice-accursed British Empire."[40]

Arrest and Deportation

On 15 April 1848, a grand jury was called on to indict not only Mitchel, but also his former associates on the Nation O'Brien and Meagher for "seditious libels". When the cases against O'Brien and Meager fell through, thanks in part to Isaac Butt's able defence, under new legislation the government replaced the charges against Mitchel with Treason Felony punishable by transportation for life. To justify the severity of new measures, under which Mitchel was arrested in May, the Home Secretary thought it sufficient to read extracts from Mitchel's articles and speeches.[41]

Convicted in June by a jury he dismissed as "packed" (as "not empanelled even according to the law of England"), Mitchel was sentenced to be "transported beyond the seas for the term of fourteen years."[39] From the dock he declared that he was satisfied that he had "shown what the law is made of in Ireland", and that he regretted nothing: "the course which I have opened is only commenced". Others would follow.[39]

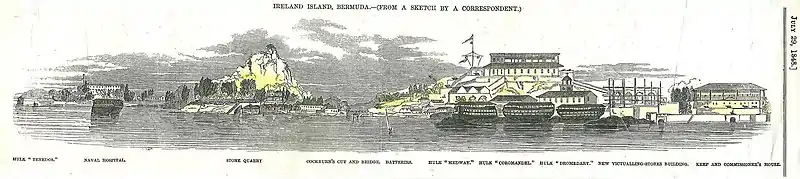

Mitchel was first transported to Ireland Island, Bermuda, where under harsh conditions the Royal Navy was using convict labour to carve out a dockyard and naval base. Surviving his time in Bermuda, in 1850 Mitchel was then sent to the penal colony of Van Diemen's Land (modern-day Tasmania, Australia). where he re-joined O'Brien and Meagher, and other Young Irelanders, convicted the wake of their abortive July 1848 rising. Aboard ship he began writing his Jail Journal, in which he reiterated his call for national unity and resistance.

The United States

Mitchel, aided by Patrick James Smyth, escaped from the Van Dieman's Land in 1853 and made his way (via Tahiti, San Francisco, Nicaragua and Cuba) to the New York. There, in January 1854, he began publishing the Irish Citizen but outlived the hero's welcome he had received. His defence of slavery in the southern states was "the subject of much surprise and general rebuke", while his advocacy of European revolution alienated the Catholic Church hierarchy.[42]

Pro-slavery Confederate

Once in the United States, Mitchel had not hesitated to repeat the claim that negroes were "an innately inferior people"[43] He denied it was a crime, "or even a peccadillo to hold slaves, to buy slaves, to keep slaves to their work by flogging or other needful correction". He, himself, might wish for "a good plantation well-stocked with healthy negroes in Alabama."[44][45]

In correspondence with his friend, the Roman Catholic priest John Kenyon, Mitchel revealed his wish to make the people of the U.S. “proud and fond of [slavery] as a national institution, and [to] advocate its extension by re-opening the trade in Negroes.” Slavery he promoted for "its own sake". It was "good in itself" for "to enslave [Africans] is impossible or to set them free either. They are born and bred slaves". The Catholic Church might condemn the "enslavement of men", but this censure could not apply to "negro slaves".[46] The value and virtue of slavery, "both for negroes and white men", he maintained from 1857 in the pages of the Southern Citizen, a paper he moved in 1859 from Knoxville, Tennessee to Washington D.C..[43]

His wife Jenny had her reservations. Nothing, she said, would induce her "to become the mistress of a slave household". Her objection to slavery was "the injury it does to the white masters".[42] There appears to be no suggestion or record of Mitchel, himself, seeking or holding any person in bondage. When he briefly farmed in eastern Tennessee it was from a log cabin and with his own labour.

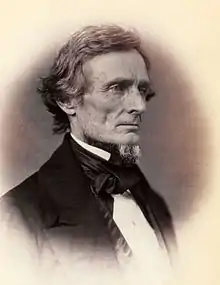

While championing the South, in the summer of 1859 Mitchel detected the possibility of a breach between France and England, from which Ireland might benefit. He travelled to Paris as an American correspondent, but found the talk of war had been much exaggerated. After the secession from the American Union of several Southern states in February 1861 and the bombardment of Fort Sumter (during which his son John commanded a South Carolina battery), Mitchel was anxious to return. He reached New York in September and made his way to the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia. There he edited the Daily Enquirer, the semi-official organ of secessionists' president, Jefferson Davis.[43]

Mitchel drew a parallel between the American South and Ireland: both were agricultural economies tied to an unjust union. The Union States and England were "..the commercial, manufacturing and money-broking power ... greedy, grabbing, griping and grovelling".[47] Abraham Lincoln he described as "... an ignoramus and a boor; not an apostle at all; no grand reformer, not so much as an abolitionist, except by accident – a man of very small account in every way."[43]

The Mitchels lost their youngest son Willie in the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, and their son John, returned to Fort Sumter, in July the following year.

After the reverse at Gettysburg Mitchel became increasingly disillusioned with Davis's leadership. In December 1863 he resigned from the Enquirer and became the leader writer for the Richmond Examiner, regularly attacking Davis for misplaced chivalry, especially his failure to retaliate in kind for Federal attacks on civilians.[48]

On slavery, Mitchel remained uncompromising. As the South's manpower reserves depleted, Generals Robert E. Lee and Patrick Cleburne (a native of County Cork) proposed that slaves should be offered their freedom in return for military service. Although he had been among the first to claim that slavery had not been not the cause of the conflict but simply the pretext for northern aggression, Mitchel objected: to allow blacks their freedom was to concede that the South had been in the wrong from the start.[43] His biographer Anthony Russell[48] notes that it was "with no trace of irony at all", that Mitchel wrote:[34]

…if freedom be a reward for negroes – that is, if freedom be a good thing for negroes – why, then it is, and always was, a grievous wrong and crime to hold them in slavery at all. If it be true that the state of slavery keeps these people depressed below the condition to which they could develop their nature, their intelligence, and their capacity for enjoyment, and what we call “progress” then every hour of their bondage for generations is a black stain upon the white race.[49]

This might have suggested that Mitchel was open to revising his view of slavery. But he remained defiant to the end, going so far as to "raise the blasphemous doubt" as to whether General Robert E. Lee was "a 'good Southerner'; that is whether he is thoroughly satisfied of the justice and beneficence of negro slavery".[50]

At odds with Irish America

At war's end in 1864 Mitchel moved to New York and edited New York Daily News. In 1865 his continued defence of southern secession caused him to be arrested in the offices of the paper and interned at Fort Monroe, Virginia, along with Jefferson Davis and Senator Henry Clay. His release was secured on condition that he left America. Mitchel returned to Paris where he acted as financial agent for the Fenians. But by 1867 he was back in New York resuming the publication of the Irish Citizen.

Mitchel's anti-Reconstruction, pro-Democratic Party editorial line was opposed in New York by another Ulster Protestant, the IRB exile David Bell.[51] Bell's "Journal of Liberty, Literature, and Social Progress", Irish Republic, cautioned readers "interested in the labor question" from associating themselves with John Mitchel (a "miserable man") and with a "diabolical" Democratic plan to impose upon blacks in the South, "as a substitute for chattel slavery, a system of serfdom scarcely less hateful than the institution it is intended to practically prolong". It claimed Mitchel defended a Democratic Party policy in the South that was nothing less than "an attempt to attach to the laborer in America those medieval conditions which even Russia [ Emancipation of the Serfs, 1861 ] has rejected".[52]

The revived Citizen failed to attract readers and folded in 1872; Bell's Irish Republic followed a year later. Neither paper was in sympathy with the ethnic-minority Catholicism powerfully represented by the city's Tammany Hall Democratic-Party political machine and, until his death in 1864, by the authority of a third Ulsterman, Archbishop John Hughes. Mitchel dedicated his paper to "aspirants to the privileges of American citizenship”, arguing that the more integrated (or "more lost") among American citizens the Irish in America were "the better”.[53]

Hughes, like Mitchel, had suggested that the conditions of "starving laborers" in the North were often worse than that of slaves in the South,[54] and in 1842 he had urged his flock not to sign O'Connell's abolitionist petition ("An Address of the People of Ireland to their Countrymen and Countrywomen in America") which he regarded as unnecessarily provocative.[30] Hughes nonetheless used Mitchel's stance on slavery to discredit him: as Mitchel saw it, "copying the abolition press to cast an Alabama plantation" in his "teeth”.[53]

Final campaign: Tipperary elections

In July 1874 Mitchel received an enthusiastic reception in Ireland (a procession of ten thousand people escorted him to his hotel in Cork). The Freeman’s Journal opined that: "After the lapse of a quarter of a century – after the loss of two of his sons … John Mitchel again treads his native land, a prematurely aged, enfeebled man. Whatever the opinions as to the wisdom of his course … none can deny the respect due to honest of purpose and fearlessness of heart".[55]

Back in New York City on 8 December 1874, Mitchel lectured on "Ireland Revisited" at the Cooper Institute, an event organized by the Clan-na-Gael and attended by among other prominent nationalists Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa. While his visit to Ireland was ostensibly private, Mitchel revealed that he had pressed to stand for British Parliament and that it was his intention, if any vacancy should occur, to offer himself as a candidate so that he might "get the Irish members to put in operation the plan suggested by O’Connell at one time, of declining to attend in Parliament altogether, that is, to try to discredit and explode the fraudulent pretence of representation in the Parliament of Britain". In the same speech, Mitchel dismissed the Irish Home Rule movement: "the fact that this Home Rule League [his friend John Martin among them] goes to Parliament and sets it hope therein, puts me in indignation against the Home Rule League … they are not Home Rulers but Foreign Rulers. Now it is painful for me to say even so much in disparagement of so excellent a body of men as they are … after a little while they will be bought".[56][57]

The call from Ireland came sooner than expected. In January 1875 a bye-election was called for a parliamentary seat in Tipperary. Stung by his remarks in New York, the Irish Parliamentary Party was reluctant to endorse Mitchel's nomination. although they may have been confused as to his position. Before re-embarking for Ireland, Mitchel issued an election address in which he appeared to endorse Home Rule—together with free education, universal tenant rights, and the freeing of Fenian prisoners.[58] As it was, on February 17, while still approaching the Irish shore, Mitchel was elected unopposed. As had been the case for O'Donovan Rossa who had been returned for very same constituency in 1869, his election was unavailing. On the motion of Benjamin Disraeli, the House of Commons by a large majority declared Mitchel, as a felon, ineligible. Mitchel ran again as an Independent Nationalist in the resulting March by-election, and in a contest took 80 percent of the vote.[59]

Mitchel died at Dromolane, his parents house in Newry, on March 20, 1875. His last letter, published on St. Patrick's Day, 17 March 1875, expressed his gratitude to the voters of Tipperary for supporting him in exposing the ‘fraudulent’ system of Irish representation in Parliament.[60] An election petition had been lodged. Observing that voters in Tipperary had known that Mitchel was ineligible, the courts awarded the seat to Mitchel's Conservative opponent.[59] At Mitchel's funeral in Newry, his friend John Martin collapsed, and died a week later.

Commemoration

On the day Mitchel died, the Tipperary paper the The Nenagh Guardian offered "An American View of John Mitchel": a syndicated piece from the Chicago Tribune that declared Mitchel a “recreant to liberty”, a defender of slavery and secession with whom “the Union masses of the American people" could have "little sympathy".[61] Obituaries for Mitchel looked elsewhere to qualify their acknowledgement of his patriotic devotion.

The Home-Rule Freeman’s Journal wrote of Mitchel: "we may lament his persistence in certain lines of action which his intelligence must have suggested to him could have but been futile issue … his love for Ireland may have been imprudent. But he loved her with a devotion unexcelled".[62] The Standard, with which Mitchel had contended in 1847, concluded: "His powers through life, however, were marred by want of judgment, obstinate opinionativeness, and a factiousness which disabled him from ever acting long enough with any set of men".[63][57]

Pádraic Pearse's remarks, just a month before he took command of the 1916 Easter Rising, may have sealed Mitchel's reputation for Irish republicans. Placed in succession to those of Theobald Wolfe Tone, Thomas Davis, and James Fintan Lalor, Pearse hailed Mitchel's "gospel of Irish nationalism" as the "fiercest and most sublime".[1] Pearse's eulogy was seconded by the Sinn Féin leader Arthur Griffith who, however, did feel constrained in a preface to a 1913 edition of Mitchel's Jail Journal, to comment that an Irish Nationalist needed no excuse for "declining to hold the negro his peer in right".[64]

In the decades following his death, branches of the Irish National Land League were named in Mitchel's honour, as were new Gaelic Athletic Association clubs. Those clubs carrying his name today include Newry Mitchel's GFC in his home town, John Mitchel's Claudy, Castlebar Mitchels GAA, and John Mitchel's Glenullin. Mitchel Park is named after him in Dungiven, near his birthplace, as is Mitchell County, Iowa, in the United States.[65] Fort Mitchel on Spike Island, cork from which he was transported in 1848 is named in his honour.

Renewed controversy

In 2018 Mitchel's racial defence of slavery again cast a shadow upon his reputation. With reference to the Black Lives Matter movement, petitions were launched, receiving over 1,200 signatures from the Newry residents, calling for a statue of Mitchel in the centre of the town to be removed, and John Mitchel Place, in which it stands, to be renamed. With the support of Unionist members who feared “creating a dangerous precedent” (people might "find other streets and names where they’d find fault with it or have some issue from a historical context"),[66] the nationalist majority Newry, Mourne and Down District Council, in June 2020, agreed only that council officers "proceed to clarify responsibility for the John Mitchel statue, develop options for an education programme, identify the origins of John Mitchel Place and give consideration as to other potential issues in relation to slavery within the council area.”[67]

Mitchel's recent biographer, Anthony Russell, who recommends that Mitchel's statue in Newry "be accompanied by at least an explanation of the context – perhaps even by a work of art condemning slavery",[68] argues that Mitchel's stand on slavery was not an aberration. His rejection of philanthropic liberalism was equal to his disdain for "free labour" political economy. In his Jail Journal Mitchel urged capital punishment for crimes such as burglary, forgery and robbery. The "reformation of offenders" was not, he argued, "the reasonable object of criminal punishment”: "Why hang them, hang them….you have no right to make the honest people support the rogues….and for 'ventilation'… I would ventilate the rascals in front of the county jails at the end of a rope".[69]

Russell suggests that, consistent with his admiration for Carlyle, Mitchel retained from his education under Dr Henderson in Newry and at Trinity College a classicist mindset of fixed hierarchies maintained, as in ancient Rome, by a ruthless lack of sentiment. The Ireland he dreamed of seeing one day free, was a rural hierarchical "pre-Enlightenment Ireland" peopled by “innumerable brave working farmers" who would never trouble themselves about “progress of the species” and such worthless ideas.[70] His earliest biographer, William Dillon, characterises Mitchel social philosophy somewhat differently.

John Mitchel had no faith in Social Utopias of any kind. In reply to the reproach that he did not believe in "the future of humanity," he once wrote to a friend--"I do believe in the future of humanity. I believe its future will be very much like its past; that is, pretty mean.[71]

As for slavery in the American South, Dillon proposed that for Mitchel it was a "practical issue". Faced with the alternative of a social system of the North in which the relation of master to servant was regulated by competition, "He took his stand in favour of the system that seemed to him the better of the two; and as was his habit, he took it decisively".[71]

Books by John Mitchel

- The Life and Times of Hugh O'Neill, James Duffy, 1845

- Jail Journal, or, Five Years in British Prisons, Office of the "Citizen", New York, 1854

- Poems of James Clarence Mangan (Introduction), P. M. Haverty, New York, 1859

- An Apology for the British Government in Ireland, Irish National Publishing Association, 1860

- The History of Ireland, from the Treaty of Limerick to the Present Time, Cameron & Ferguson, Glasgow, 1864

- The Poems of Thomas Davis (Introduction), D. & J. Sadlier & Co., New York, 1866

- The Last Conquest of Ireland (Perhaps), Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873

- The Crusade of the Period, Lynch, Cole & Meehan 1873

- Reply to the Falsification of History by James Anthony Froude, Entitled 'The English in Ireland', Cameron & Ferguson n.d.

References

- Pearse, P. H. (1916). The Sovereign People (PDF). Dublin: Whelan. p. 10. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- William Dillon, The life of John Mitchel (London, 1888) 2 Vols. Ch I-II

- William Dillon, The Life of John Mitchel (London, 1888) 2 Vols. Ch III

- McGovern, Bryan P. (2009). John Mitchel: Irish Nationalist, Southern Secessionist. Knoxville: University of Tennessee. pp. 12, 15. ISBN 9781572336544. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Mitchel, John (1905). An Apology for the British Government in Ireland. Dublin: O'Donoghue. p. 65.

- Young Ireland, T.F. O'Sullivan, The Kerryman Ltd, 1945.

- The Nation newspaper, 1845

- The Nation newspaper, 1844

- The Nation newspaper, 1846

- Woodham-Smith, Cecil (1962). The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845–1849. London: Penguin. pp. 410–411. ISBN 978-0-14-014515-1.

- Geoghegan, Patrick (2010). Liberator Daniel O'Connell: The Life and Death of Daniel O'Connell, 1830-1847. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. p. 332.

- Finton Lalor to Duffy, January, 1847 (Gavan Duffy Papers).

- Finton Lalor to Duffy, February, 1847 (Gavan Duffy Papers).

- McCullagh, John. "Irish Confederation formed". newryjournal.co.uk/. Newry Journal. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- O'Sullivan (1945). Young Ireland. The Kerryman Ltd. pp. 195-6

- Michael Doheny’s The Felon’s Track, M.H. Gill & Son, LTD, 1951 Edition pg 111–112

- Huggins, Michael (2012). "A Strange Case of Hero-Worship: John Mitchel and Thomas Carlyle". Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies (2): 329–352. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- T. Carlyle to C. G. Duffy, 19 January 1846, Ms 5756, National Library of Ireland, Dublin

- Huggins (2012) p. 336

- Mitchel, John (1845). The Life and Times of Aodh O'Neill, Prince of Ulster. Dublin: J. Duffy. p. v-vi.

- Thomas Carlyle (1843), "Repeal of the Act of Union", in Percy Newberry (ed.) Rescued Essays of Thomas Carlyle, London, Leadenhall, 1892, pp. 17-52

- Dugger, Julie M (2006). "Black Ireland's Race: Thomas Carlyle and the Young Ireland Movement". Victorian Studies. 48 (3): 461–485. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1849). "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question". Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. Vol. 40.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1882). Reminiscences of my Irish Journey 1849. New York: Harper Brothers. p. 214-215.

- O'Connell, an address in Conciliation Hall, in Dublin on September 29, 1845 recorded by Frederick Douglass in a letter to William Lloyd Garrison. Christine Kinealy ed. (2018), Frederick Douglass and Ireland: In His Own Words, Volume II. Routledge, New York. ISBN 9780429505058. Pages 67, 72.

- Duffy, Charles Gavan (1898). My Life in Two Hemispheres. London: Macmillan. p. 70. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- See also Duffy, Charles Gavan (1883). Four Years of Irish History, 1845-1849. Dublin: Cassell, Petter, Galpin. pp. 500–501. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- Jenkins, Lee (Autumn 1999). "Beyond the Pale: Frederick Douglass in Cork" (PDF). The Irish Review (24): 92.

- "Daniel O'Connell and the campaign against slavery". historyireland.com. History Ireland. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- Kinealy, Christine. "The Irish Abolitionist: Daniel O'Connell". irishamerica.com. Irish America. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1849). "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question". Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. Vol. 40.

- Higgins, Michael (2012). "A Strange Case of Hero-Worship: John Mitchel and Thomas Carlyle". Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies (2): 329–352. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Gleeson, David (2016) Failing to 'unite with the abolitionists': the Irish Nationalist Press and U.S. emancipation. Slavery & Abolition, 37 (3). pp. 622-637. ISSN 0144-039X

- Roy, David (11 July 2015). "John Mitchel: a rebel with two causes remembered". Irish News. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Froude, James Anthony (1884). Thomas Carlyle: a History of his Life. Volume 1. London: Longman, Green and Co. p. 399.

- William Theobald Wolfe Tone, ed. (1826). Life of Theobald Wolfe Tone, vol. 2. Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton. p. 45. ISBN 9781108081948.

- The United Irishman, 1848

- For the full text of the letter see here.

- P.A. Sillard, Life of John Mitchel, James Duffy and Co. Ltd, 1908

- "United Irishman (Dublin, Ireland : 1848) v. 1 no. 16". digital.library.villanova.eduUnited Irishman (Dublin, Ireland : 1848) v. 1 no. 16. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Four Years of Irish History 1845–1849, Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co. 1888

- O Cathaoir, Brendan (31 December 1999). "An Irishman's Diary". Irish Times. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Quinn, James. "Southern Citizen: John Mitchel, the Confederacy and slavery". History Ireland. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- The Great Dan, Charles Chevenix Trench, Jonathan Cape Ltd, (London 1984), p. 274.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 215.

- Fogarty, Lillian (1921). Fr. John Kenyon – A Patriot Priest of '48. Dublin: Whelan & Son. p. 163.

- James Patrick Byrne; Philip Coleman; Jason Francis King (2008). Ireland and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History : a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 597. ISBN 978-1-85109-614-5.

- Russell, Anthony (2015). Between Two Flags: John Mitchel & Jenny Verner. Dublin: Merion Press. ISBN 9781785370007.

- Dillon, William (1888). The Life of John Mitchel (vol. 2). London: Kegan Paul, Trench &Co. p. 109. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Quinlan, Kieran (2005). Strange Kin: Ireland and the American South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 93. ISBN 0807129836.

- Knight, Matthew (2017). "The Irish Republic: Reconstructing Liberty, Right Principles, and the Fenian Brotherhood". Éire-Ireland (Irish-American Cultural Institute). 52 (3 & 4): 252–271. doi:10.1353/eir.2017.0029. S2CID 159525524. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "Spirit of the Press". The Irish Republic. 2 (1): 6. 4 January 1868. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- Collopy, David (24 February 2020). "Unholy row – An Irishman's Diary on John Mitchel and Archbishop John Hughes". The Irish Times. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Nelson, Bruce (2012). Irish Nationalists and the Making of the Irish Race. Princeton University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0691153124.

- Freeman’s Journal. 27 July 1874.

- The Irishman, 2 January 1875

- Mitchel, Patrick. "John Mitchel's Return to Ireland 1874-75". FaithinIreland. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Our Own Correspondent, "Mr. John Mitchell." Times, London, England, 6 Feb. 1875

- Sullivan, A. M. "John Mitchel, the Story of Ireland, A. M. Sullivan (c 1900), Chapter XCL (continued)". Library Ireland. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Freeman’s Journal, March 17, 1875.

- The Nenagh Guardian, 20 March 1875

- Freeman’s Journal, 22 March 1875

- Standard, 22 March 1875

- Arthur Griffith (1913), preface to John Mitchel, Jail Journal. M H Gill, Dublin, 1913

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 210.

- Kula, Adam (9 June 2020). "Demand to strip pro-slavery figure's name of Newry Street 'risks dangerous precedents". News Letter. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Young, Connla. "Council to establish responsibility for John Mitchel statue". Irish News (23 June 2020). Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Russell, Anthony (7 February 2018). "Should Irish slavery supporter John Mitchel's statue in Newry be taken down?". Irish Times. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Mitchel, John (1864). Jail Journal, or Five Years in British Prisons. Dublin: James Corrigan. p. 142. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- Russell, Anthony (2015). Between Two Flags: John Mitchel & Jenny Verner. Dublin: Merion Press. pp. 212–213. ISBN 9781785370007.

- Dillon, William (1888). The Life of John Mitchel (vol. 2). London: Kegan Paul, Trench &Co. p. 114. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Mitchel. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Mitchel |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Biographies of Mitchel

- The life of John Mitchel, William Dillon, (London, 1888) 2 Vols.

- Life of John Mitchel, P.A. Sillard, James Duffy and Co., Ltd 1908

- John Mitchel: An Appreciation, P.S. O'Hegarty, Maunsel & Company, Ltd 1917

- Mitchel's Election a National Triumph, Charles J. Rosebault, J. Duffy, 1917

- Irish Mitchel, Seamus MacCall, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd 1938

- John Mitchel: First Felon for Ireland, Edited By Brian O'Higgins, Brian O'Higgins 1947

- John Mitchel Noted Irish Lives, Louis J. Walsh, The Talbot Press Ltd 1934

- John Mitchel, Ó Cathaoir, Brendan (Clódhanna Teoranta, Dublin, 1978)

- John Mitchel, A Cause Too Many, Aidan Hegarty, Camlane Press 2005

- John Mitchel: Irish Nationalist, Southern Secessionist, Bryan McGovern, (Knoxville, 2009)

- Between Two Flags: John Mitchel & Jenny Verner, Anthony Russell (Dublin, Merion Press, 2015)

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Charles William White William O'Callaghan |

Member of Parliament for Tipperary 1875 Served alongside: William O'Callaghan |

Succeeded by Stephen Moore William O'Callaghan |