Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León[1] (Spanish pronunciation: [xwan ˈponθe ðe leˈon]; 1474 – July 1521[2]), commonly known as Ponce de León (/ˌpɒns də ˈliːən/,[3] also UK: /ˌpɒnseɪ də leɪˈɒn/,[4] US: /ˌpɒns də liˈoʊn, ˌpɒns(ə) deɪ -/[5][6]), was a Spanish explorer and conquistador known for leading the first official European expedition to Florida and serving as the first governor of Puerto Rico. He was born in Santervás de Campos, Valladolid, Spain in 1474. Though little is known about his family, he was of noble birth and served in the Spanish military from a young age. He first came to the Americas as a "gentleman volunteer" with Christopher Columbus's second expedition in 1493.

Juan Ponce de León | |

|---|---|

17th century engraving of Ponce de León (unauthenticated) | |

| 1st, 3rd and 7th Governor of Puerto Rico | |

| In office 1508–1509 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Juan Cerón |

| In office 1510–1511 | |

| Preceded by | Juan Cerón |

| Succeeded by | Juan Cerón |

| In office 1515–1519 | |

| Preceded by | Cristóbal de Mendoza |

| Succeeded by | Sánchez Velázquez/Antonio de la Gama |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1474 Santervás de Campos, Castile |

| Died | July 1521 (aged 46–47) Havana, Cuba |

| Resting place | Catedral Metropolitana Basílica de San Juan Bautista, San Juan, Puerto Rico |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Spouse(s) | (name unknown), Leonor Ponce de León |

| Relations |

|

| Profession | Explorer |

| Signature |  |

By the early 1500s, Ponce de León was a top military official in the colonial government of Hispaniola, where he helped crush a rebellion of the native Taíno people. He was authorized to explore the neighboring island of Puerto Rico in 1508 and for serving as the first Governor of Puerto Rico by appointment of the Spanish crown in 1509. While Ponce de León grew quite wealthy from his plantations and mines, he faced an ongoing legal conflict with Diego Columbus, the late Christopher Columbus's son, over the right to govern Puerto Rico. After a long court battle, Columbus replaced Ponce de León as governor in 1511. Ponce de León decided to follow the advice of the sympathetic King Ferdinand and explore more of the Caribbean Sea.

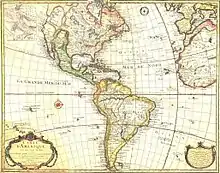

In 1513, Ponce de León led the first known European expedition to La Florida, which he named during his first voyage to the area. He landed somewhere along Florida's east coast, then charted the Atlantic coast down to the Florida Keys and north along the Gulf coast, perhaps as far as Charlotte Harbor. Though in popular culture he was supposedly searching for the Fountain of Youth, there is no contemporary evidence to support the story, which all modern historians call a myth.[7]

Ponce de León returned to Spain in 1514 and was knighted by King Ferdinand, who also re-instated him as the governor of Puerto Rico and authorized him to settle Florida. He returned to the Caribbean in 1515, but plans to organize an expedition to Florida were delayed by the death of King Ferdinand in 1516, after which Ponce de León again traveled to Spain to defend his grants and titles. He would not return to Puerto Rico for two years.

In 1521, Ponce de León finally returned to southwest Florida with the first large-scale attempt to establish a Spanish colony in what is now the continental United States. However, the native Calusa people fiercely resisted the incursion, and he was seriously wounded in a skirmish. The colonization attempt was abandoned, and its leader died from his wounds soon after returning to Cuba. Ponce de León was interred in Puerto Rico, and his tomb is located inside of the Cathedral of San Juan Bautista in San Juan. According to John J. Browne Ayes, 30% of the modern population of Puerto Rico descend from Juan Ponce de León and his wife.[8]

Spain

Juan Ponce de León was born in the village of Santervás de Campos in the northern part of what is now the Spanish province of Valladolid. Although early historians placed his birth in 1460, and this date has been used traditionally, more recent evidence shows he was likely born in 1474.[9] The surname Ponce de León dates from the 13th century. The Ponce de León lineage began with Ponce Vélaz de Cabrera, descendant of count Bermudo Núñez, and Sancha Ponce de Cabrera,[10] daughter of Ponce Giraldo de Cabrera. Before October 1235, a son of Ponce Vela de Cabrera and his wife Teresa Rodríguez Girón named Pedro Ponce de Cabrera[11] married Aldonza Alfonso, an illegitimate daughter of King Alfonso IX of León.[11] The descendants of this marriage added the "de León" to their patronymic and were known henceforth as the Ponce de León.

The identity of his parents is still unknown, but he appears to have been a member of a distinguished and influential noble family. His relatives included Rodrigo Ponce de León, Marquis of Cádiz, a celebrated figure in the Moorish wars.[12]

Ponce de León was related to another notable family, the Núñez de Guzmáns, and as a young man he served as squire to Pedro Núñez de Guzmán, Knight Commander of the Order of Calatrava.[13] A contemporary chronicler, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, states that Ponce de León gained his experience as a soldier fighting in the Spanish campaigns that defeated the Moors in Granada and completed the re-conquest of Spain in 1492.[14]

Arrival in the New World

Once the war against the Emirate of Granada ended, there was no apparent need for his military services at home, so, like many of his contemporaries, Ponce de León looked abroad for his next opportunity.[13] In September 1493, some 1,200 sailors, colonists, and soldiers joined Christopher Columbus for his second voyage to the New World.[15] Ponce de León was a member of this expedition, one of 200 "gentleman volunteers."[16]

The fleet reached the Caribbean in November 1493. They visited several islands before arriving at their primary destination in Hispaniola.[17] In particular they anchored on the coast of a large island the natives called Borinquen but would eventually become known as Puerto Rico. This was Ponce de León's first glimpse of the place that would play a major role in his future.[18]

Historians are divided on what he did during the next several years, but it is possible that he returned to Spain at some point and made his way back to Hispaniola with Nicolás de Ovando.[19]

Hispaniola

In 1502 the newly appointed governor, Nicolás de Ovando, arrived in Hispaniola. The Spanish Crown expected Ovando to bring order to a colony in disarray.[15][20] Ovando interpreted this as authorizing subjugation of the native Taínos. Thus, Ovando authorized the Jaragua massacre in November 1503. In 1504, when Tainos overran a small Spanish garrison in Higüey on the island's eastern side, Ovando assigned Ponce de León to crush the rebellion.[20] Ponce de León was actively involved in the Higüey massacre, about which friar Bartolomé de las Casas attempted to notify Spanish authorities. Ovando rewarded his victorious commander by appointing him frontier governor of the newly conquered province, then named Higüey also. Ponce de León received a substantial land grant which authorized sufficient Indian slave labor to farm his new estate.[21]

Ponce de León prospered in this new role. He found a ready market for his farm produce and livestock at nearby Boca de Yuma where Spanish ships stocked supplies before the long voyage back to Spain. In 1505 Ovando authorized Ponce de León to establish a new town in Higüey, which he named Salvaleón. In 1508 King Ferdinand (Queen Isabella having opposed the exploitation of natives but dying in 1504) authorized Ponce de León to conquer the remaining Taínos and exploit them in gold mining.[22]

Around this time, Ponce de León married Leonora, an innkeeper's daughter. They had three daughters (Juana, Isabel and Maria) and one son (Luis). The large stone house Ponce de León ordered built for his growing family still stands today near the city of Salvaleón de Higüey.[23]

Puerto Rico

As provincial governor, Ponce de León had occasion to meet with the Taínos who visited his province from neighboring Puerto Rico. They told him stories of a fertile land with much gold to be found in the many rivers. Inspired by the possibility of riches, Ponce de León requested and received permission from Ovando to explore the island.[24]

His first reconnaissance of the island is usually dated to 1508 but there is evidence that he had made a previous exploration as early as 1506. This earlier trip was done quietly because the Spanish crown had commissioned Vicente Yáñez Pinzón to settle the island in 1505. Pinzón did not fulfill his commission and it expired in 1507, leaving the way clear for Ponce de León.[25]

His earlier exploration had confirmed the presence of gold and gave him a good understanding of the geography of the island. In 1508, Ferdinand II of Aragon gave permission to Ponce de León for the first official expedition to the island, which the Spanish then called San Juan Bautista. This expedition, consisting of about 50 men in one ship, left Hispaniola on 12 July, 1508 and eventually anchored in San Juan Bay, near today's city of San Juan.[26] Ponce de León searched inland until he found a suitable site about two miles from the bay. Here he erected a storehouse and a fortified house, creating the first settlement in Puerto Rico, Caparra.[27] Although a few crops were planted, the settlers spent most of their time and energy searching for gold. By early 1509 Ponce de León decided to return to Hispaniola. His expedition had collected a good quantity of the precious metal but was running low on food and supplies.[28]

The expedition was deemed a great success and Ovando appointed Ponce de León governor of San Juan Bautista. This appointment was later confirmed by Ferdinand II on 14 August, 1509. He was instructed to extend the settlement of the island and continue mining for gold. The new governor returned to the island as instructed, bringing with him his wife and children.[29]

Back on his island, Ponce de León parceled out the native Taínos amongst himself and other settlers using a system of forced labor known as encomienda.[30] The Indians were put to work growing food crops and mining for gold. Many of the Spaniards treated the Taínos very harshly and newly introduced diseases like smallpox and measles took a severe toll on the local population. By June 1511 the Taínos were pushed to a short-lived rebellion, which was forcibly put down by Ponce de León and a small force of troops armed with crossbows and arquebuses.[31][32]

Even as Ponce de León was settling the island of San Juan, significant changes were taking place in the politics and government of the Spanish West Indies. On 10 July, 1509, Diego Colón, the son of Christopher Columbus, arrived in Hispaniola as acting Viceroy, replacing Nicolás de Ovando.[33] For several years Diego Colón had been waging a legal battle over his rights to inherit the titles and privileges granted to his father. The Crown regretted the sweeping powers that had been granted to Columbus and his heirs and sought to establish more direct control in the New World. In spite of the Crown's opposition, Colón prevailed in court and Ferdinand was required to appoint him Viceroy.[34] Although the courts had ordered that Ponce de León should remain in office, Colón circumvented this directive on 28 October, 1509 by appointing Juan Ceron chief justice and Miguel Diaz chief constable of the island, effectively overriding the authority of the governor.[35] This situation prevailed until 2 March, 1510, when Ferdinand issued orders reaffirming Ponce de León's position as governor. Ponce de León then had Ceron and Diaz arrested and sent back to Spain.[35]

The political struggle between Colón and Ponce de León continued in this manner for the next few years. Ponce de León had influential supporters in Spain and Ferdinand regarded him as a loyal servant. However, Colón's position as Viceroy made him a powerful opponent and eventually it became clear that Ponce de León's position on San Juan was not tenable.[36] Finally, on 28 November, 1511, Ceron returned from Spain and was officially reinstated as governor.[37]

First voyage to Florida

Rumors of undiscovered islands to the northwest of Hispaniola had reached Spain by 1511, and Ferdinand was interested in forestalling further exploration and discovery by Colón. In an effort to reward Ponce de León for his services, Ferdinand urged him to seek these new lands outside the authority of Colón. Ponce de León readily agreed to a new venture, and in February 1512 a royal contract was dispatched outlining his rights and authorities to search for "the Islands of Benimy".[38]

The contract stipulated that Ponce de León held exclusive rights to the discovery of Benimy and neighboring islands for the next three years. He would be governor for life of any lands he discovered, but he was expected to finance for himself all costs of exploration and settlement. In addition, the contract gave specific instructions for the distribution of gold, Native Americans, and other profits extracted from the new lands. Notably, there was no mention of a rejuvenating fountain.[39][40]

Ponce de León equipped three ships with at least 200 men at his own expense and set out from Puerto Rico on 4 March, 1513. The only near contemporary description known for this expedition comes from Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, a Spanish historian who apparently had access to the original ships' logs or related secondary sources from which he created a summary of the voyage published in 1601.[41][42] The brevity of the account and occasional gaps in the record have led historians to speculate and dispute many details of the voyage.

The three ships in this small fleet were the Santiago, the San Cristobal and the Santa Maria de la Consolacion. Anton de Alaminos was their chief pilot. He was already an experienced sailor, and would become one of the most respected pilots in the region. After leaving Puerto Rico, they sailed northwest along the great chain of Bahama Islands, known then as the Lucayos. On 27 March, Easter Sunday, they sighted an island that was unfamiliar to the sailors on the expedition. Because many Spanish seamen were acquainted with the Bahamas, which had been depopulated by slaving ventures, some scholars believe that this "island" was actually Florida, as it was thought to be an island for several years after its formal discovery.[43] Other scholars have speculated that this island was one of the northern Bahama islands, perhaps Great Abaco.[44]

For the next several days the fleet crossed open water until 2 April, 1513, when they sighted land which Ponce de León believed was another island. He named it La Florida in recognition of the verdant landscape and because it was the Easter season, which the Spaniards called Pascua Florida (Festival of Flowers). The following day they came ashore to seek information and take possession of this new land..[45][46] The precise location of their landing on the Florida coast has been disputed for many years. Some historians believe it occurred at or near St. Augustine;[47] others prefer a more southern landing at a small harbor now called Ponce de León Inlet;[45] but some also believe that Ponce came ashore even farther south near the present location of Melbourne Beach,[48][49][50] a theory that has been criticized by some scholars in recent years.[51] The latitude coordinate recorded in the ship's log closest to the landing site, reported by Herrera (who had the original logbook) in 1601, was 30 degrees, 8 minutes.[43][52] This sighting was recorded at noon the day before with either a quadrant or a mariner's astrolabe, and the expedition sailed north for the remainder of the day before anchoring for the night and rowing ashore the following morning. This latitude corresponds to a spot north of St. Augustine between what is now the Guana Tolomato Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve and Ponte Vedra Beach.[43][53]

After remaining in the area of their first landing for about five days, the ships turned south for further exploration of the coast. On 8 April they encountered a current so strong that it pushed them backwards and forced them to seek anchorage. The tiniest ship, the San Cristobal, was carried out of sight and lost for two days. This was the first encounter with the Gulf Stream where it reaches maximum force between the Florida coast and the Bahamas. Because of the powerful boost provided by the current, it would soon become the primary route for eastbound ships leaving the Spanish Indies bound for Europe.[54]

They continued down the coast hugging the shore to avoid the strong head current. By 4 May the fleet reached and named Biscayne Bay and took on water at an island they named Santa Marta (now Key Biscayne) and explored the Tequesta Miami mound town at the mouth of the Miami River. The Tequesta did not engage the Spanish, they evacuated into the coastal woodlands. On 15 May they left Biscayne Bay and sailed along the Florida Keys, looking for a passage to head north and explore the west coast of the Florida peninsula. From a distance the Keys reminded Ponce de León of men who were suffering, so he named them Los Martires (the Martyrs).[54] Eventually they found a gap in the reefs and sailed "to the north and other times to the northeast" until they reached the Florida mainland on 23 May, where they encountered the Calusa, who refused to trade and drove off the Spanish ships by surrounding them with warriors in sea canoes armed with long bows.[55][56]

Again, the exact site of their landfall is controversial. The vicinity of Charlotte Harbor is the most commonly identified spot, while some assert a landing further north at Tampa Bay or even Pensacola.[58] Other historians have argued the distances were too great to cover in the available time and the more likely location was Cape Romano or Cape Sable.[58] Here Ponce de León anchored for several days to take on water and repair the ships. They were approached by Calusa, who might have been initially interested in trading but relations soon turned hostile. Several skirmishes followed with casualties on both sides and the Spaniards took eight Indians captive,[59] including one to become a translator.[20] On 4 June, there was another encounter with natives near Sanibel Island and the Calusa in war canoes, with the Spanish sinking a fourth of them. An unsubstantiated claim to justify Spanish retreat.[60]

On 14 June they set sail again looking for a chain of islands in the west that had been described by their captives. They reached the Dry Tortugas on 21 June.[20] There they captured giant sea turtles, Caribbean monk seals, and thousands of seabirds. From these islands they sailed southwest in an apparent attempt to circle around Cuba and return home to Puerto Rico. Failing to take into account the powerful currents pushing them eastward, they struck the northeast shore of Cuba and were initially confused about their location.[61]

Once they regained their bearings, the fleet retraced their route east along the Florida Keys and around the Florida peninsula, reaching Grand Bahama on 8 July. They were surprised to come across another Spanish ship, piloted by Diego Miruelo, who was either on a slaving voyage or had been sent by Diego Colón to spy on Ponce de León. Shortly thereafter Miruelo's ship was wrecked in a storm and Ponce de León rescued the stranded crew.

From here the little fleet disbanded. Ponce de León tasked the Santa Maria with further exploration while he returned home with the rest of crew. Ponce de León reached Puerto Rico on 19 October after having been away for almost eight months. The other ship, after further explorations returned safely on 20 February, 1514.[62]

Although Ponce de León is widely credited with the discovery of Florida, he almost certainly was not the first European to reach the peninsula. Spanish slave expeditions had been regularly raiding the Bahamas since 1494 and there is some evidence that one or more of these slavers made it as far as the shores of Florida.[63] Another piece of evidence that others came before Ponce de León is the Cantino Map from 1502, which shows a peninsula near Cuba that looks like Florida's and includes characteristic place names.

Fountain of Youth

According to a popular legend, Ponce de León discovered Florida while searching for the Fountain of Youth. Though stories of vitality-restoring waters were known on both sides of the Atlantic long before Ponce de León, the story of his searching for them was not attached to him until after his death. In his Historia general y natural de las Indias of 1535, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés wrote that Ponce de León was looking for the waters of Bimini to cure his aging.[64] A similar account appears in Francisco López de Gómara's Historia general de las Indias of 1551.[65] Then in 1575, Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, a shipwreck survivor who had lived with the Native Americans of Florida for 17 years, published his memoir in which he locates the waters in Florida, and says that Ponce de León was supposed to have looked for them there.[66] Though Fontaneda doubted that Ponce de León had really gone to Florida looking for the waters, the account was included in the Historia general de los hechos de los castellanos of Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas of 1615. Most historians hold that the search for gold and the expansion of the Spanish Empire were far more imperative than any potential search for such a fountain.[67][68]

There is a possibility that the Fountain of Youth was an allegory for the Bahamian love vine, which locals brew today as an aphrodisiac. Ponce de León could have been seeking it as a potential entrepreneurial venture. Woodrow Wilson believed Indian servants brewing a "brown tea" in Puerto Rico may have inspired Ponce de León's search for the Fountain of Youth.[69] Arne Molander has speculated that the adventurous conquistador mistook the natives' "vid" (vine) for "vida" (life) – transforming their "fountain vine" into an imagined "fountain of life".

Between voyages

Upon his return to Puerto Rico, Ponce de León found the island in turmoil. A party of Caribs from a neighboring island had attacked the settlement of Caparra, killed several Spaniards and burned it to the ground. Ponce de León's own house was destroyed and his family narrowly escaped. Colón used the attack as a pretext for renewing hostilities against the local Taíno tribes. The explorer suspected that Colón was working to further undermine his position on the island and perhaps even to take his claims for the newly discovered Florida.[70]

Ponce de León decided he should return to Spain and personally report the results of his recent expedition. He left Puerto Rico in April 1514 and was warmly received by Ferdinand when he arrived at court in Valladolid. There he was knighted,[20] and given a personal coat of arms, becoming the first conquistador to receive these honors. He also visited Casa de Contratación in Seville, which was the central bureaucracy and clearinghouse for all of Spain's activities in the New World. The Casa took detailed notes of his discoveries and added them to the Padrón Real, a master map which served as the basis for official navigation charts provided to Spanish captains and pilots.[71]

During his stay in Spain, a new contract[72] was drawn up for Ponce de León confirming his rights to settle and govern Bimini and Florida,[73] which was then presumed to be an island. In addition to the usual directions for sharing gold and other valuables with the king, the contract was one of the first to stipulate that the Requerimiento was to be read to the inhabitants of the islands prior to their conquest. Ponce de León was also ordered to organize an armada for the purpose of attacking and subduing the Caribs, who continued to attack Spanish settlements in the Caribbean.[74]

Three ships were purchased for his armada and after repairs and provisioning Ponce de León left Spain on 14 May, 1515 with his little fleet. The record of his activities against the Caribs is vague. There was one engagement in Guadeloupe on his return to the area and possibly two or three other encounters.[75] The campaign came to an abrupt end in 1516 when Ferdinand died. The king had been a strong supporter and Ponce de León felt it was imperative he return to Spain and defend his privileges and titles. He did receive assurances of support from Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, the regent appointed to govern Castile, but it was nearly two years before he was able to return home to Puerto Rico.

Meanwhile, there had been at least two unauthorized voyages to "his" Florida both ending in repulsion by the native Calusa Tequesta warriors. Ponce de León realized he had to act soon if he was to maintain his claim.

Last voyage to Florida

In early 1521, Ponce de León organized a colonizing expedition consisting of some 200 men, including priests, farmers and artisans, 50 horses and other domestic animals, and farming implements carried on two ships. The expedition landed somewhere on the coast of southwest Florida, likely in the vicinity of Charlotte Harbor or the Caloosahatchee River, areas which Ponce de León had visited in his earlier voyage to Florida.[76]

Before the settlement could be established, the colonists were attacked by the Calusa, the indigenous people who dominated southern Florida and whose principal town was nearby. Ponce de León was mortally wounded in the skirmish when, historians believe, an arrow poisoned with the sap of the manchineel tree struck his thigh.[77] The expedition immediately abandoned the colonization attempt and sailed to Havana, Cuba, where Ponce de León soon died of his wounds. He was buried in Puerto Rico, in the crypt of San José Church from 1559 to 1836, when his remains were exhumed and transferred to the Cathedral of San Juan Bautista.[78]

Legacy and honors

- The World War II Liberty Ship SS Ponce De Leon was named in his honor.

See also

Bibliography

| Library resources about Juan Ponce de León |

- Allen, John Logan (1997). A New World Disclosed. University of Nebraska Press.

- Arnade, Charles W. (1967). "Who Was Juan Ponce de León?" Tequesta, The Journal of the Historical Association of Southern Florida. XXVII, 29–58.

- Davis, T. Frederick. (1935) "History of Juan Ponce de León's Voyages to Florida: Source Records." Florida Historical Society Quarterly. V14:1.

- Devereux, Anthony Q. (1993). Juan Ponce de Leon, King Ferdinand, and the Fountain of Youth. Spartanburg, South Carolina: The Reprint Company, Publishers. ISBN 0871524643.

- Fuson, Robert H. (2000). Juan Ponce de León and the Discovery of Puerto Rico and Florida. McDonald & Woodward Publishing Co.

- Kessell, John L. (2003). Spain in the Southwest: A Narrative History of Colonial New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, and California. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Lawson, Edward W. (1946). The Discovery of Florida and Its Discoverer Juan Ponce de León. Reprint, Kessenger Publishing.

- Marley, David. (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere (2 Volumes). ABC-CLIO.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1974). The European Discovery of America, The Southern Voyages. Oxford University Press.

- Peck, Douglas T. (1993). Ponce de León and the Discovery of Florida: The Man, the Myth, and the Truth Pogo Press.

- Salazar y Acha, Jaime de (1985). "Una Familia de la Alta Edad Media: Los Velas y su Realidad Histórica". Estudios Genealógicos y Heráldicos (in Spanish). Madrid: Asociación Española de Estudios Genealógicos y Heráldicos. ISBN 84-398-3591-4.

- Torres Sevilla-Quiñones de León, Margarita Cecilia (1999). Linajes nobiliarios de León y Castilla: Siglos IX-XIII (in Spanish). Salamanca: Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de educación y cultura. ISBN 84-7846-781-5.

- Turner, Samuel P. (2012). "The Caribbean World of Juan Ponce de León and His Discovery of Florida". Paper presented at the Culturally La Florida Conference, 3–6 May, St. Augustine, Florida.

- Turner, Samuel (2013) "Juan Ponce de León and the Discovery of Florida Reconsidered" Florida Historical Quarterly 92(1):1–31.

- Van Middeldyk, R. A. (1903). The History of Puerto Rico. D. Appleton and Co.

- Weddle, Robert S. (1985). Spanish Sea: the Gulf Of Mexico in North American Discovery, 1500–1685. Texas A&M University Press.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

References

- Robert Greenberger (3 December 2005). Juan Ponce de León: The Exploration of Florida and the Search for the Fountain of Youth. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8239-3627-4.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1974). The European Discovery of America: the Southern voyages A.D. 1492–1616. Oxford University Press. pp. 502, 515.

- "Ponce de León". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Ponce de León, Juan". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Ponce de León". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- "Ponce de León". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- Greenspan, Jesse (2 April 2013). "The Myth of Ponce de León and the Fountain of Youth". History. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- John J. Browne Ayes, "Juan Ponce de León, the new and revised genealogy",2012 (take into account that, even though this book is backed by 15 years of research with documents and DNA, and is detailed, the author is not a geneticist)

- Morison 1974, p. 502, 529.

- Torres Sevilla-Quiñones de León 1999, p. 188.

- Torres Sevilla-Quiñones de León 1999, p. 191.

- Arnade, pp. 35–44

- Van Middeldyk, p. 11

- Morison 1974, p. 502

- L. Kessel, John (2003). Spain in the Southwest: A Narrative History of Colonial New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, and California. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1928874201.

- Morison 1974, p. 100

- Van Middeldyk, pp. 12–15

- Morison 1974, pp. 112–115.

- Fuson, pp. 56–57.

- David Marley (February 2008). Wars of the Americas: a chronology of armed conflict in the Western Hemisphere, 1492 to the present. ABC-CLIO. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-1-59884-100-8.

- Fuson, pp. 63–65.

- Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos- Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus pg. 155. Yale University Press. New Haven : Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05181-6.

- Fuson, pp. 66–67.

- Van Middeldyk, pp. 17–19.

- Fuson, pp. 72–75

- Marley 2008, pp. 12–13

- Lawson, p. 3.

- Fuson, pp. 75–77

- Lawson, pp. 3–4

- Van Middeldyk, pp. 27–29

- Van Middeldyk, pp. 36–41

- Floyd, Troy (1973). The Columbus Dynasty in the Caribbean, 1492–1526. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 135.

- Lawson, p. 4

- Kessel 2003, p. 10

- Van Middeldyk, p. 18

- Lawson, pp. 5–7

- Fuson, p. 95.

- Fuson, pp. 88–91.

- Weddle, p. 40.

- See contract translated by Fuson, pp. 92–95 or Lawson, pp. 84–88.

- Fuson, pp. 99–103 and Weddle, p. 51.

- See Fuson, pp. 103–115 for complete Herrera account.

- "Turner 2012, p. 5" (PDF).

- Weddle, p. 40–41.

- Morison 1974, p. 507

- Jonathan D. Steigman (25 September 2005). La Florida Del Inca and the Struggle for Social Equality in Colonial Spanish America. University of Alabama Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8173-5257-8.

- Lawson, pp. 29–32

- Peck, p. 39.

- Moody, Norman (21 April 2011). "Naming barrier island would honor state find". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 1A.

- Datzman, Ken. "Did the famous explorer Ponce de León first hit Melbourne Beach", Brevard Business News, vol 30, no. 1 (Melbourne, Florida: 2 January 2012), p. 1 and 19.

- Turner 2013:15–17

- Turner 2013:9–15

- Turner 2013:14–15

- Weddle, p. 42.

- Weddle, pp. 43–44.

- Douglas, The Everglades, River of Grass.

- San Juan municipality Archived 2 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Allen, pp.215–216.

- Weddle, pp. 43–45.

- Marley2008, p. 17

- Weddle, p. 45.

- Weddle, pp. 46–47.

- Fuson, pp. 88–89.

- Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo. Historia general y natural de las Indias, book 16, chapter XI.

- Francisco López de Gómara. Historia General de las Indias, second part.

- "Fontaneda's Memoir". Translation by Buckingham Smith, 1854. From keyshistory.org. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- Douglas, Marjory Stoneman (1947). The Everglades: River of Grass. Pineapple Press. ISBN 9781561641352. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- Carl Ortwin Sauer (1 January 1975). Sixteenth Century North America: The Land and the People as Seen by the Europeans. University of California Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-520-02777-0.

- Woodrow Wilson, "History of the American People, New York and Amsterdam: Harper and Brothers, 1917, Vol 1, p. 13

- Fuson, p. 121–124.

- Fuson, pp. 125–127.

- See Fuson, pp. 129–131 for complete translation.

- William Robert Shepherd (1907). Guide to the Materials for the History of the United States in Spanish Archives. Carnegie institution of Washington. p. 68.

- Fuson, pp. 128–132.

- Fuson, pp. 136–138.

- Davis, T. Frederick (1935). "Ponce de Leon's Second Voyage and Attempt to Colonize Florida". The Florida Historical Society Quarterly. 14 (1): 51–66. ISSN 0361-624X. JSTOR 30150209.

- Grunwald, Michael (2007). The Swamp. Simon & Schuster. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7432-5107-5.

- Fuson, pp. 173–176.

.

External links

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Yale University Genocide Studies on Puerto Rico

- Turner, Samuel P. (2012) "The Caribbean World of Juan Ponce de León and His Discovery of Florida". Paper presented at the Culturally La Florida Conference, May 3–6, St. Augustine, Florida.

| Preceded by none |

Governor of Puerto Rico 1508–1511 |

Succeeded by Juan Cerón |

| Preceded by Cristóbal de Mendoza |

Governor of Puerto Rico 1515–1519 |

Succeeded by Sánchez Velázquez |