John Dickinson

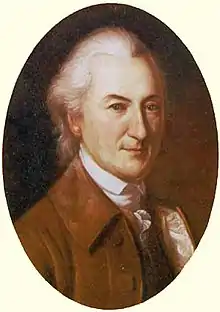

John Dickinson (November 13 [Julian calendar November 2] 1732[note 1] – February 14, 1808), a Founding Father of the United States, was a solicitor and politician from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Wilmington, Delaware, known as the "Penman of the Revolution" for his twelve Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, published individually in 1767 and 1768. As a member of the First Continental Congress, where he was a signee to the Continental Association, Dickinson drafted most of the 1774 Petition to the King, and then, as a member of the Second Continental Congress, wrote the 1775 Olive Branch Petition. When these two attempts to negotiate with King George III of Great Britain failed, Dickinson reworked Thomas Jefferson's language and wrote the final draft of the 1775 Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms. When Congress then decided to seek independence from Great Britain, Dickinson served on the committee that wrote the Model Treaty, and then wrote the first draft of the 1776–1777 Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union.

John Dickinson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5th President of Pennsylvania | |

| In office November 7, 1782 – October 18, 1785 | |

| Vice President | James Ewing James Irvine Charles Biddle |

| Preceded by | William Moore |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Franklin |

| President of Delaware | |

| In office November 13, 1781 – January 12, 1783 | |

| Preceded by | Caesar Rodney |

| Succeeded by | John Cook |

| Continental Congressman from Delaware | |

| In office January 18, 1779 – February 10, 1781 | |

| Continental Congressman from Pennsylvania | |

| In office August 2, 1774 – November 7, 1776 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nov 2 Jul./Nov 13Greg., 1732[note 1] Talbot County, Province of Maryland, British America |

| Died | February 14, 1808 (aged 75) Wilmington, Delaware, U.S. |

| Resting place | Friends Burial Ground, Wilmington |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Mary (Polly) Norris |

| Residence | Kent County, Delaware Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Wilmington, Delaware |

Dickinson later served as President of the 1786 Annapolis Convention, which called for the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Dickinson attended the Convention as a delegate from Delaware.

He also wrote "The Liberty Song" in 1768, was a militia officer during the American Revolution, President of Delaware, President of Pennsylvania, and was among the wealthiest men in the British American colonies. Upon Dickinson's death, President Thomas Jefferson recognized him as being "Among the first of the advocates for the rights of his country when assailed by Great Britain whose 'name will be consecrated in history as one of the great worthies of the revolution.'"[1]

Together with his wife, Mary Norris Dickinson, he is the namesake of Dickinson College (originally John and Mary's College), as well as of the Dickinson School of Law of Pennsylvania State University and the University of Delaware's Dickinson Complex. John Dickinson High School was opened/dedicated in 1959 as part of the public schools in northern Delaware.

Family history

Dickinson was born[note 1] at Croisadore, his family's tobacco plantation near the village of Trappe in Talbot County, Province of Maryland.[2] He was the great-grandson of Walter Dickinson who emigrated from England to Virginia in 1654 and, having joined the Society of Friends, came with several co-religionists to Talbot County on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay in 1659. There, with 400 acres (1.6 km2) on the banks of the Choptank River, Walter began a plantation, Croisadore, meaning "cross of gold." Walter also bought 800 acres (3.2 km2) on St. Jones Neck in what became Kent County, Delaware.[3]

Croisadore passed through Walter's son, William, to his grandson, Samuel, the father of John Dickinson. Each generation increased the landholdings, so that Samuel inherited 2,500 acres (1,000 ha) on five farms in three Maryland counties and over his lifetime increased that to 9,000 acres (3,600 ha). He also bought the Kent County property from his cousin and expanded it to about 3,000 acres (1,200 ha), stretching along the St. Jones River from Dover to the Delaware Bay. There he began another plantation and called it Poplar Hall. These plantations were large, profitable agricultural enterprises worked by slave labor, until 1777 when John Dickinson freed the enslaved of Poplar Hall.[4]

Samuel Dickinson first married Judith Troth (1689–1729) on April 11, 1710. They had nine children; William, Walter, Samuel, Elizabeth, Henry, Elizabeth "Betsy," Rebecca, and Rachel. The three eldest sons died of smallpox while in London seeking their education. Widowed, with two young children, Henry and Betsy, Samuel married Mary Cadwalader in 1731. She was the daughter of Martha Jones (granddaughter of Dr. Thomas Wynne) and the prominent Quaker John Cadwalader who was also grandfather of General John Cadwalader of Philadelphia. Their sons, John, Thomas, and Philemon were born in the next few years.

For three generations the Dickinson family had been members of the Third Haven Friends Meeting in Talbot County and the Cadwaladers were members of the Meeting in Philadelphia. But in 1739, John Dickinson's half-sister, Betsy, was married in an Anglican church to Charles Goldsborough in what was called a "disorderly marriage" by the Meeting. The couple would be the grandparents of Maryland governor Charles Goldsborough.

Leaving Croisadore to elder son Henry Dickinson, Samuel moved to Poplar Hall, where he had already taken a leading role in the community as Judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Kent County. The move also placed Mary nearer her Philadelphia relations.

Poplar Hall was situated on a now-straightened bend of the St. Jones River. There was plenty of activity delivering the necessities, and shipping the agricultural products produced. Much of this product was wheat that along with other wheat from the region, was milled into a "superfine" flour.[5]Most people at this plantation were servants and slaves of the Dickinsons.

Early life and family

_and_Daughter%252C_Sallie_Norris_Dickinson.jpg.webp)

Dickinson was educated at home by his parents and by recent immigrants employed for that purpose. Among them was the Presbyterian minister Francis Alison, who later established New London Academy in Chester County, Pennsylvania.[6] Most important was his tutor, William Killen, who became a lifelong friend and who later became Delaware’s first Chief Justice and Chancellor. Dickinson was precocious and energetic, and in spite of his love of Poplar Hall and his family, was drawn to Philadelphia.

At 18 he began studying the law under John Moland in Philadelphia. There he made friends with fellow students George Read and Samuel Wharton, among others. By 1753, John went to London for three years of study at the Middle Temple. He spent those years studying the works of Edward Coke and Francis Bacon at the Inns of Court, following in the footsteps of his lifelong friend, Pennsylvania Attorney General Benjamin Chew,[7] and in 1757 was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar beginning his career as barrister and solicitor.

In protest to the Townshend Acts, Dickinson published Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. First published in the Pennsylvania Chronicle, Dickinson's letters were re-printed by numerous other newspapers and became one of the most influential American political documents prior to the American Revolution. Dickinson argued that Parliament had the right to regulate commerce, but lacked the right to levy duties for revenue. Dickinson further warned that if the colonies acquiesced to the Townshend Acts, Parliament would lay further taxes on the colonies in the future.[8] After publishing these letters, he was elected in 1768 to the American Philosophical Society as a member.[9]

On July 19, 1770, Dickinson married Mary Norris, known as Polly, a prominent and well educated thirty-year-old woman in Philadelphia with a substantial holding of real estate and personal property (including a 1500 volume library, one of the largest in the colonies at the time) who had been operating her family's estate, Fair Hill, for a number of years by herself or with her sister. She was the daughter of a wealthy Philadelphia Quaker, and Speaker of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, Isaac Norris and Sarah Logan, the daughter of James Logan, both deceased.[10] She was also cousin to the Quaker poet Hannah Griffitts. Dickinson and Norris had five children, but only two survived to adulthood: Sarah Norris "Sally" Dickinson and Maria Mary Dickinson. Dickinson never formally joined the Quaker Meeting, because, as he explained, he believed in the "lawfulness of defensive war".[11] He and Norris were married in a civil ceremony.

In Philadelphia, he lived at his wife's property, Fair Hill, near Germantown, which they modernized through their combined wealth. Meanwhile, he built an elegant mansion on Chestnut Street but never lived there as it was confiscated and turned into a hospital during his 1776–77 absence in Delaware.[12] It then became the residence of the French ambassador and still later the home of his brother, Philemon Dickinson. Fair Hill was burned by the British during the Battle of Germantown. While in Philadelphia as State President, he lived at the confiscated mansion of Joseph Galloway at Sixth and Market Streets, now established as the State Presidential mansion.

Dickinson lived at Poplar Hall, for extended periods only in 1776–77 and 1781–82. In August 1781 it was sacked by Loyalists and was badly burned in 1804. This home is now owned by the State of Delaware and is open to the public.[13] After his service as President of Pennsylvania, he returned to live in Wilmington, Delaware in 1785 and built a mansion at the northwest corner of 8th and Market Streets.

Continental Congress

Dickinson was one of the delegates from Pennsylvania to the First Continental Congress in 1774 and the Second Continental Congress in 1775 and 1776. In support of the cause, he continued to contribute declarations in the name of the Congress. Dickinson wrote the Olive Branch Petition as the Second Continental Congress' last attempt for peace with Britain (King George III did not even read the petition). But through it all, agreeing with New Castle County's George Read and many others in Philadelphia and the Lower Counties, Dickinson's object was reconciliation, not independence and revolution.

When the Continental Congress began the debate on the Declaration of Independence on July 1, 1776, Dickinson reiterated his opposition to declaring independence at that time. Dickinson believed that Congress should complete the Articles of Confederation and secure a foreign alliance before issuing a declaration. Dickinson also objected to violence as a means for resolving the dispute. He abstained or absented himself from the votes on July 2 that declared independence and absented himself again from voting on the wording of the formal Declaration on July 4. Dickinson understood the implications of his refusal to vote stating, "My conduct this day, I expect will give the finishing blow to my once too great and, my integrity considered, now too diminished popularity."[14] Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration and since a proposal had been brought forth and carried that stated "for our mutual security and protection" no man could remain in Congress without signing, Dickinson voluntarily left and joined the Pennsylvania militia.[15] John Adams, a fierce advocate for independence and Dickinson's adversary on the floor of Congress, remarked, "Mr. Dickinson's alacrity and spirit certainly become his character and sets a fine example."[16]

Following the Declaration of Independence, Dickinson was given the rank of brigadier general in the Pennsylvania militia, known as the Associators. He led 10,000 soldiers to Elizabeth, New Jersey, to protect that area against British attack from Staten Island. But because of his unpopular opinion on independence, two junior officers were promoted above him.[17]

Return to Poplar Hall

Dickinson resigned his commission in December 1776 and went to stay at Poplar Hall in Kent County. While there he learned that his home on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia had been confiscated and converted into a hospital. He stayed at Poplar Hall for more than two years. The Delaware General Assembly tried to appoint him as their delegate to the Continental Congress in 1777, but he refused. In August 1777 he served as a private with the Kent county Militia at Middletown, Delaware under General Caesar Rodney to help delay General William Howe's march to Philadelphia. In October 1777, Dickinson's friend, Thomas McKean, appointed him Brigadier General of the Delaware Militia, but again Dickinson declined the appointment. Shortly afterwards he learned that the British had burned down his and his wife's Fairhill property during the Battle of Germantown.[18]

These years were not without accomplishment however. In 1777, Dickinson, Delaware's wealthiest farmer and largest slaveholder,[19] decided to free his slaves. While Kent County was not a large slave-holding area, like farther south in Virginia, and even though Dickinson had only 37 slaves,[20] this was an action of some considerable courage. Undoubtedly, the strongly abolitionist Quaker influences around them had their effect,[21] and the action was all the easier because his farm had moved away from tobacco to the less labor-intensive crops like wheat and barley.[22] Furthermore, manumission was a multi-year process and many of the workers remained obligated to service for a considerable additional time.

Dickinson was the only founding father to free his slaves in the period between 1776 and 1786.[23] Benjamin Franklin had freed his slaves by 1770.

Drafting of the Articles of Confederation

Dickinson prepared the first draft of the Articles of Confederation in 1776, after others had ratified the Declaration of Independence over his objection that it would lead to violence, and to follow through on his view that the colonies would need a governing document to survive war against them.

At the time he chaired the committee, charged with drafting the Articles, Dickinson was serving in the Continental Congress as a delegate from Pennsylvania. The Articles he drafted are based around a concept of "person", rather than "man" as was used in the Declaration of Independence, although they do refer to "men" in the context of armies.[24]

President of Delaware

On January 18, 1779, Dickinson was appointed to be a delegate for Delaware to the Continental Congress. During this term he signed the Articles of Confederation, having in 1776 authored their first draft while serving in the Continental Congress as a delegate from Pennsylvania. In August 1781, while still a delegate in Philadelphia he learned that Poplar Hall had been severely damaged by a Loyalist raid. Dickinson returned to the property to investigate the damage and once again stayed for several months.

While there, in October 1781, Dickinson was elected to represent Kent County in the State Senate, and shortly afterwards the Delaware General Assembly elected him the president of Delaware. The General Assembly's vote was nearly unanimous, the only dissenting vote having been cast by Dickinson himself.[25] Dickinson took office on November 13, 1781 and served until November 7, 1782. Beginning his term with a "Proclamation against Vice and Immorality," he sought ways to bring an end to the disorder of the days of the Revolution. It was a popular position and enhanced his reputation both in Delaware and Pennsylvania. Dickinson then successfully challenged the Delaware General Assembly to address lagging militia enlistments and to properly fund the state’s assessment to the Confederation government. And recognizing the delicate negotiations then underway to end the American Revolution, Dickinson secured the Assembly's continued endorsement of the French alliance, with no agreement on a separate peace treaty with Great Britain. He also introduced the first census.

However, as before, the lure of Pennsylvania politics was too great. On October 10, 1782, Dickinson was elected to the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. On November 7, 1782 a joint ballot by the Council and the Pennsylvania General Assembly elected him as president of the Council and thereby President of Pennsylvania. But he did not actually resign as State President of Delaware. Even though Pennsylvania and Delaware had shared the same governor until very recently, attitudes had changed, and many in Delaware were upset at seemingly being cast aside so readily, particularly after the Philadelphia newspapers began criticizing the state for allowing the practice of multiple and non resident office holding. Dickinson’s constitutional successor, John Cook, was considered too weak in his support of the Revolution, and it was not until January 12, 1783, when Cook called for a new election to choose a replacement, that Dickinson formally resigned.

| Delaware General Assembly (sessions while President) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Assembly | Senate Majority | Speaker | House Majority | Speaker | ||||||

| 1781/82 | 6th | non-partisan | Thomas Collins | non-partisan | Simon Kollock | ||||||

| 1782/83 | 7th | non-partisan | Thomas Collins | non-partisan | Nicholas Van Dyke | ||||||

President of Pennsylvania

When the American Revolution began, Dickinson fairly represented the center of Pennsylvania politics. The old Proprietary and Popular parties divided equally in thirds over the issue of independence, as did Loyalists, Moderate Whigs who later became Federalists, and Radicals or Constitutionalists. The old Pennsylvania General Assembly was dominated by the Loyalists and Moderates and, like Dickinson, did little to support the burgeoning Revolution or independence, except protest. The Radicals took matters into their own hands, using irregular means to write the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, which by law excluded from the franchise anyone who would not swear loyalty to the document or the Christian Holy Trinity. In this way all Loyalists, Moderate Whigs, and Quakers were kept out of government. This peremptory action seemed appropriate to many during the crises of 1777 and 1778, but less so in the later years of the Revolution, and the Moderate Whigs gradually became the majority.

Dickinson's election to the Supreme Executive Council was the beginning of a counterrevolution against the Constitutionalists. He was elected President of Pennsylvania on November 7, 1782, garnering 41 votes to James Potter's 32. As president he presided over the intentionally weak executive authority of the state, and was its chief officer, but always required the agreement of a majority to act. He was re-elected twice and served the constitutional maximum of three years; his election on November 6, 1783 was unanimous. On November 6, 1784 he defeated John Neville, who also lost the election for Vice-President the same day. Working with only the smallest of majorities in the General Assembly in his first two years and with the Constitutionalists in the majority in his last year, all issues were contentious. At first he endured withering attacks from his opponents for his alleged failure to fully support the new government in large and small ways. He responded ably and survived the attacks. He managed to settle quickly the old boundary dispute with Virginia in southwestern Pennsylvania, but was never able to satisfactorily disentangle disputed titles in the Wyoming Valley resulting from prior claims of Connecticut to those lands. An exhausted Dickinson left office October 18, 1785. On that day a special election was held in which Benjamin Franklin was unanimously elected to serve the ten days left in Dickinson's term.

Perhaps the most significant decision of his term was his patient, peaceful management of the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783. This was a violent protest of Pennsylvania veterans who marched on the Continental Congress demanding their pay before being discharged from the army. Somewhat sympathizing with their case, Dickinson refused Congress's request to bring full military action against them, causing Congress to vote to remove themselves to Princeton, New Jersey. And when the new Congress agreed to return in 1790, it was to be for only 10 years, until a permanent capital was found elsewhere.

| Pennsylvania General Assembly (sessions while President) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Assembly | Majority | Speaker | ||||||||

| 1782/83 | 7th | Republican | Frederick A. C. Muhlenberg | ||||||||

| 1783/84 | 8th | Republican | George Gray | ||||||||

| 1784/85 | 9th | Constitutional | John Bubenheim Bayard | ||||||||

John and Mary's College

In 1784, Dickinson and Mary Norris Dickinson bequeathed much of their combined library to John and Mary's College, named in their honor by its founder Benjamin Rush and later renamed Dickinson College.[26][27] The Dickinsons also donated 500 acres (2 km²) in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, land originally inherited and managed by Mary Norris, to the new college.

United States Constitution

After his service in Pennsylvania, Dickinson returned to Delaware, and lived in Wilmington. He was quickly appointed to represent Delaware at the Annapolis Convention, where he served as its president. In 1787, Delaware sent him as one of its delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, along with Gunning Bedford Jr., Richard Bassett, George Read, and Jacob Broom. There, he supported the effort to create a strong central government but only after the Great Compromise assured that each state, regardless of size, would have an equal vote in the future United States Senate. As he had done with the Articles, he also carefully drafted it with the term "Person" rather than "Man" as was used in the Declaration of Independence. He prepared initial drafts of the First Amendment. Following the Convention he promoted the resulting Constitution in a series of nine essays, written under the pen name Fabius.

In 1791, Delaware convened a convention to revise its existing Constitution, which had been hastily drafted in 1776. Dickinson was elected president of this convention, and although he resigned the chair after most of the work was complete, he remained highly influential in the content of the final document. Major changes included the establishment of a separate Chancery Court and the expansion of the franchise to include all taxpayers, except blacks and women. Dickinson remained neutral in an attempt to include a prohibition of slavery in the document, believing the General Assembly was the proper place to decide that issue. The new Constitution was approved June 12, 1792. Dickinson himself had freed his slaves conditionally in 1776 and fully by 1787.

Once more Dickinson was returned to the State Senate for the 1793 session, but served for just one year before resigning due to his declining health. In his final years, he worked to further the abolition movement, and donated a considerable amount of his wealth to the "relief of the unhappy". In 1801, Dickinson published two volumes of his collected works on politics.

Education and Religion

John Dickinson was a self-taught scholar of history, and spent most of his time in historical research. As an intellectual, he thought that men should think for themselves,[28] and his deepening studies led him to refuse to sign the Declaration of Independence. He did not think it wise to plunge into immediate war, rather, he thought it best to use diplomacy to attain political ends, and used the insights he gained from his historical studies to justify his caution.[29] Given that Dickinson was raised in an aristocratic family, his cautious and thoughtful temperament as a Quaker gave rise to his conservatism and prudent behavior. As Dickinson became more politically savvy, his understanding of historical movements led him to become a revolutionary.[30] Dickinson was very careful and refined in thought.[31] Dickinson wrote in 1767, "We cannot act with too much caution in our disputes. Anger produces anger; and differences, that might be accommodated by kind and respectful behavior, may, by imprudence, be enlarged to an incurable rage."[32] He did not behave rashly, insisting that prudence was the key to great politics. Dickinson used his study of history and furthered his education to become a lawyer, which exposed him to more historical schooling.[33] His education and religion allowed him to make important political decisions based on reason and sound judgment. John Powell states, "...these forces of Puritanism had a vigorous expression. It is precisely because Dickinson epitomized the philosophic tenets of the Puritan Revolution that his theories were of enormous importance in the formation of the Constitution, and have considerable meaning for us today."[34] His studies of history and religious viewpoints had a profound impact on his political thought and actions.[35]

Dickinson incorporated his learning and religious beliefs to counteract what he considered the mischief flowing from the perversion of history and applied them to its proper use according to his understanding.[36] His religiosity contributed heavily to his discernment of politics. Quakers disseminated their theologico-political thought aggressively and retained a significant measure of political influence.[37] Dickinson's political thought, given his education and religion, was influential towards the founding of the United States. The political theory of Quakers was informed by their theology and ecclesiology,[38] consequently Dickinson applied his religious beliefs and his belief in adhering to the letter of the law in his approach to the Constitution,[39] referring to his historical knowledge as he did so. Quakers did use secular history as a guide for their political direction, and they considered scripture the most important historical source.[40]

Death and legacy

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | John Dickinson (1732–1808) |

| Type | Roadside |

| Criteria | American Revolution, Government & Politics 18th Century, Military |

| Designated | September 23, 2001 |

| Location | Montgomery Ave. at Haverford Ave., Narberth |

| Marker Text | Statesman, author. In influential writings, 1765–74, argued against British policies. Later, as a member, Continental Congress, 1774–76, favored conciliation and opposed the Declaration of Independence; nonetheless, served the patriot cause as colonel, 1st Philadelphia Battalion. President, Pa. Supreme Executive Council, 1782–85. Delegate, U.S. Constitutional Convention, 1787; a strong supporter of the Constitution. Deeded land to Merion Meeting, 1801–04. |

Dickinson died at Wilmington, Delaware and was buried in the Friends Burial Ground.[41]

In an original copy of a letter discovered November 2009 from Thomas Jefferson to Joseph Bringhurst, caretaker of Dickinson in his later years, Jefferson responded to news of Dickinson's death: "A more estimable man, or truer patriot, could not have left us. Among the first of the advocates for the rights of his country when assailed by Great Britain, he continued to the last the orthodox advocate of the true principles of our new government and his name will be consecrated in history as one of the great worthies of the revolution."[1][42]

He shares with Thomas McKean the distinction of serving as Chief Executive of both Delaware and Pennsylvania after the Declaration of Independence. Dickinson College and Dickinson School of Law (now of the Pennsylvania State University), separate institutions each operating a campus located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, on land inherited and managed by his wife Mary Norris, were named for them. Dickinson College was originally named "John and Mary's College" but was renamed to avoid an implication of royalty by confusion with "William and Mary." And along with his Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, Dickinson also authored The Liberty Song.

Dickinson Street in Madison, Wisconsin is named in his honor,[43] as is John Dickinson High School in Milltown, Delaware, and Dickinson Hall at the University of Delaware.

Almanac

Delaware elections were held October 1 and members of the General Assembly took office on October 20 or the following weekday. The State Legislative Council was created in 1776 and its Legislative Councilmen had a three-year term. Beginning in 1792 it was renamed the State Senate. State Assemblymen had a one-year term. The whole General Assembly chose the State President for a three-year term.

Pennsylvania elections were held in October as well. Assemblymen had a one-year term. The Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council was created in 1776, and counsellors were popularly elected for three-year terms. A joint ballot of the Pennsylvania General Assembly and the Council chose the president from among the twelve counsellors for a one-year term. Both assemblies chose the Continental Congressmen for a one-year term as well as the delegates to the U.S. Constitution Convention.

| Delaware General Assembly service | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | Assembly | Chamber | Majority | Governor | Committees | District |

| 1781/82 | 6th | State House | non-partisan | Caesar Rodney | Kent at-large | |

| 1793 | 17th | State Senate | Republican | Joshua Clayton | New Castle at-large | |

In popular culture

Dickinson is a prominent character in the musical drama 1776, billed third after the parts of Adams and Franklin. He was originally portrayed on stage by Paul Hecht, and in the 1972 film adaptation by Donald Madden. Michael Cumpsty portrayed him in the 1997 revival. His portrayal in this musical differs substantially from reality: instead of abstaining from voting and debating, he acts as John Adams' primary antagonist in the debates over independence, to the point where the two men come to blows. His motivation in the musical is to convince the delegates to come to peace terms with Britain, rather than to seek reforms through civil disobedience and other nonviolent measures and for the colonies to mature before seeking independence. Also his wife Mary Norris does not appear in the musical at all, despite being present in Philadelphia at the time, whereas Abigail Adams and Martha Jefferson are heavily depicted, despite being in Boston and Virginia, respectively, at the time.

In 1997 John Dickinson is portrayed by actor Victor Garber in Liberty! The American Revolution

In Part II of the 2008 HBO series John Adams, based on the book by David McCullough, the part of Dickinson is played by Zeljko Ivanek.

In Michael Flynn's Alternative History "The Forest of Time", depicting a history in which the Constitutional Convention failed and the Thirteen Colonies went each its own way as fully sovereign Nation States, Dickinson was the First Head of State of the sovereign Pennsylvania.

As portrayed in the 2015 miniseries Sons of Liberty Dickinson is shown continually speaking out against prematurely fighting the British and voting on the idea of a Declaration of Independence. He suggests a request first be made from the Continental Congress to the British King, in the form of the Olive Branch Petition. The program gives no indication that Dickinson would author the petition. As the Congress votes on independence, the miniseries portrays Dickinson getting up and leaving the room without explanation, and no summary was given of his overall contributions to the American Revolution or what would become of him later.

Dickinson was honored with a brief mention in season 7, episode 4 of South Park, "I'm a Little Bit Country".

Notes

- Various sources indicate a birth date of November 8, November 12 or November 13, but his most recent biographer, Flower, offers November 2 without dispute.

References

- "UD Library discovers Thomas Jefferson letter". University of Delaware. December 3, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- National Archives and Records Administration: "America's Founding Fathers: Delegates to the Constitutional Convention."

- The Duke of York Record 1646–1679, Printed by order of the General Assembly of the State of Delaware, 1899

- "John Dickinson: timeline". Historyhome.co.uk. January 5, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- Hoffecker, Carol E. "Democracy in Delaware: The Story of the First State's General Assembly." Cedar Tree Books (2004), 39.

- "History – University of Delaware". www.udel.edu. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- Publications of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: Life and Writings of John Dickinson [vol. 1], pg.28.

- Middlekauff, Robert (2005). The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution 1763–1789. Oxford University Press. pp. 161–162.

- Bell, Whitfield J., and Charles Greifenstein, Jr. Patriot-Improvers: Biographical Sketches of Members of the American Philosophical Society. 3 vols. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1997, 1:383–390.

- Stillé, Charles Janeway, The Life and Times of John Dickinson. 1732–1808 (Philadelphia, 1891).

- Flower, Milton Embick (1983). John Dickinson: Conservative Revolutionary. University of Virginia Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-8139-0966-0.

- Ferling, John (2011). Independence: The Struggle to Set America Free. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press. p. 132. ISBN 9781608193974.

- John Dickinson Plantation. State of Delaware, Department of State, Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs. Accessed January 6, 2017.

- Murchison, William (February 18, 2014). "Who Was Delaware's John Dickinson and Why You Should Care". Delaware Today.

- Wright, Robert K. and MacGregor, Jr., Morris J. "Soldier-Statesmen of the Constitution." Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C. (1987), 82-84.

- Smith 1962, p. 285.

- Wright, Robert K. and MacGregor, Jr., Morris J. "Soldier-Statesmen of the Constitution." Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C. (1987), 82-84.

- Publications of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: Life and Writings of John Dickinson [vol. 1], 315.

- Gregg II, Gary L. and Hall, Mark David. "America's Forgotten Founders." University of Louisville (2008), 97.

- Gregg II, Gary L. and Hall, Mark David. "America's Forgotten Founders." University of Louisville (2008), 97.

- Gregg II, Gary L. and Hall, Mark David. "America's Forgotten Founders." University of Louisville (2008), 97.

- Hoffecker, Carol E. "Democracy in Delaware: The Story of the First State's General Assembly." Cedar True Books (2004), 40.

- Calvert, Jane E. "John Dickinson Writings Project". University of Kentucky: The John Dickinson Writings Project. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- "Journals of the Continental Congress – Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union; July 12, 1776". The Avalon Project of Yale Law School. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- Bushman, Claudia L.; Hancock, Harold Bell; Homsey, Elizabeth Moyne (1988). Proceedings of the House of Assembly of the Delaware State, 1781–1792, and of the Constitutional Convention of 1792. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-87413-309-7. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- "The Books of Isaac Norris at Dickinson College". The Dickinson Electronic Initiative in the Liberal Arts. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- Butterfield, L.H. (1948). Benjamin Rush and the Beginning of John and Mary's College Over the Susquehanna. Oxford Journals: Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. p. 427.

- Colbourn, Trevor H. "John Dickinson, Historical Revolutionary." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 83, no. 3 (1959): 271.

- Colbourn, Trevor H. "John Dickinson, Historical Revolutionary." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 83, no. 3 (1959): 286.

- Colbourn, Trevor H. "John Dickinson, Historical Revolutionary." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 83, no. 3 (1959): 273.

- Powell, John H. "John Dickinson and the Constitution." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 60, no. 1 (1936): 5.

- Powell, John H. "John Dickinson and the Constitution." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 60, no. 1 (1936): 6.

- Colbourn, Trevor H. "John Dickinson, Historical Revolutionary." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 83, no. 3 (1959): 273.

- Powell, John H. "John Dickinson and the Constitution." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 60, no. 1 (1936): 11.

- Colbourn, Trevor H. "John Dickinson, Historical Revolutionary." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 83, no. 3 (1959): 279.

- Charles J. Stille. "The Life and Times of John Dickinson 1732-1808." Kessinger Publishing, LLC (2010), 330

- Jane E. Calvert. "Quaker Constitutionalism and the Political Thought of John Dickinson." Cambridge University Press (2008), 279.

- Jane E. Calvert. "Quaker Constitutionalism and the Political Thought of John Dickinson." Cambridge University Press (2008), 67.

- Charles J. Stille. "The Life and Times of John Dickinson 1732-1808." Kessinger Publishing, LLC (2010), 378.

- Jane E. Calvert. “Quaker Constitutionalism and the Political Thought of John Dickinson.” Cambridge University Press (2008), 285.

- Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. p. 217. ISBN 0-19-503186-5

- "Student finds letter 'a link to Jefferson'". CNN.com. December 8, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- "Odd Wisconsin Archives". Wisconsinhistory.org. March 29, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

Bibliography

- Calvert, Jane E. (July 2007). "Liberty Without Tumult: Understanding the Politics of John Dickinson". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania. CXXXI (3): 233–62.

- —— (2008). Quaker Constitutionalism and the Political Thought of John Dickinson. Cambridge, England, and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521884365.

- Colbourn, Trevor H. "John Dickinson, Historical Revolutionary." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 83, no. 3 (1959).

- Conrad, Henry C. (1908). History of the State of Delaware. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Wickersham Company.

- Flower, Milton E. (1983). John Dickinson – Conservative Revolutionary. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-0966-X.

- Hoffecker, Carol E. (2004). Democracy in Delaware. Wilmington, Delaware: Cedar Tree Books. ISBN 1-892142-23-6.

- Martin, Roger A. (1984). History of Delaware Through its Governors. Wilmington, Delaware: McClafferty Press.

- —— (1995). Memoirs of the Senate. Newark, Delaware: Roger A. Martin.

- Munroe, John A. (1954). Federalist Delaware 1775–1815. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University.

- —— (2004). Philadelawareans. Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0-87413-872-8.

- Powell, John H. "John Dickinson and the Constitution." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 60, no. 1 (1936).

- Racino, John W. (1980). Biographical Directory of American and Revolutionary Governors 1607–1789. Westport, CT: Meckler Books. ISBN 0-930466-00-4.

- Rodney, Richard S. (1975). Collected Essays on Early Delaware. Wilmington, Delaware: Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Delaware.

- Richards, Robert Haven (1901). The life and character of John Dickinson. Wilmington : The Historical society of Delaware.

- Scharf, John Thomas (1888). History of Delaware 1609–1888. 2 vols. Philadelphia: L. J. Richards & Co.

- Smith, Page (1962). John Adams. Volume I, 1735–1784. New York, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc.

- Stillé, Charles J. (1891). The life and times of John Dickinson.

- Ward, Christopher L. (1941). Delaware Continentals, 1776–1783. Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware. ISBN 0-924117-21-4.

- Bushman, Claudia L.; Hancock, Harold Bell; Homsey, Elizabeth Moyne (1988). Proceedings of the House of Assembly of the Delaware State, 1781–1792, and of the Constitutional Convention of 1792. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-309-7. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Dickinson (politician). |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: John Dickinson |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Dickinson |

- Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Delaware's Governors

- Delmarva Heritage Series

- Revolution to Reconstruction

- Soldier-Statesmen of the Constitution

- University of Pennsylvania Archives

- ExplorePAHistory.com

- The R.R. Logan Collection of John Dickinson Papers are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Works by or about John Dickinson at Internet Archive

- Works by John Dickinson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- More information

- Delaware Historical Society – website

- University of Delaware – Library website

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania – website

- John Dickinson Plantation – website

- Wilmington Quaker Meeting House (burial site)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Caesar Rodney |

President of Delaware 1781–1783 |

Succeeded by John Cook |

| Preceded by William Moore |

President of Pennsylvania November 7, 1782 – October 18, 1785 |

Succeeded by Benjamin Franklin |