Independence Hall

The Independence Hall is the building where both the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted. It is now the centerpiece of the Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[3]

| Independence Hall | |

|---|---|

South façade of Independence Hall | |

| Location | 520 Chestnut Street between 5th and 6th Streets, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 39°56′56″N 75°9′0″W |

| Architect | William Strickland (steeple) |

| Architectural style(s) | Georgian |

| Visitors | 645,564 (in 2005[1]) |

| Governing body | National Park Service[2] |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 78 |

| State Party | United States |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Part of | Independence National Historical Park |

| Reference no. | 66000683[2] |

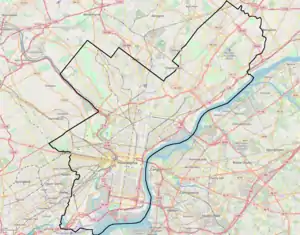

Location of Independence Hall in Philadelphia  Independence Hall (Pennsylvania)  Independence Hall (the United States) | |

The building was completed in 1753 as the Pennsylvania State House, and served as the capitol for the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania until the state capital moved to Lancaster in 1799. It became the principal meeting place of the Second Continental Congress from 1775 to 1783 and was the site of the Constitutional Convention in the summer of 1787.

A convention held in Independence Hall in 1915, presided over by former US president William Howard Taft, marked the formal announcement of the formation of the League to Enforce Peace, which led to the League of Nations and eventually the United Nations. The building is part of Independence National Historical Park and is listed as a World Heritage Site.[4]

Preparation for construction

By the spring of 1729, the citizens of Philadelphia were petitioning to be allowed to build a state house; 2,000 pounds were committed to the endeavor. A committee composed of Thomas Lawrence, John Kearsley, and Andrew Hamilton was charged with the responsibility of selecting a site for construction, acquiring plans for the building, and contracting a company for construction of the building. Hamilton and William Allen were named trustees of the purchasing and building fund and authorized to buy the land that would be the site of the state house. By October 1730 they had begun purchasing lots on Chestnut Street.[5]

By 1732, even though Hamilton had acquired the deed for Lot no. 2 from surveyor David Powell, who had been paid for his work with the lot, tensions were rising among the committee members. Kearsley and Hamilton disagreed on a number of issues concerning the state house. Kearsley, who is credited with the designs of both Christ Church and St. Peter's Church, had plans for the structure of the building, but so did Hamilton. The two men also disagreed on the building's site; Kearsley suggested High Street, now Market Street, and Hamilton favored Chestnut Street. Lawrence said nothing on the matter.[6]

Matters reached a point where arbitration was needed. On August 8, 1733, Hamilton brought the matter before the House of Representatives. He explained that Kearsley did not approve of Hamilton's plans for the location and architecture of the state house and went on to insist the House had not agreed to these decisions. In response to this, Hamilton, on August 11, showed his plans for the state house to the House, who accepted them. On August 14, the House sided with Hamilton, granting him full control over the project, and the site on the south side of Chestnut Street between Fifth and Sixth Streets was chosen for the location of the state house. Ground was broken for construction soon after.[7]

Structure

Independence Hall touts a red brick facade, designed in Georgian style. It consists of a central building with belltower and steeple, attached to two smaller wings via arcaded hyphens. The highest point to the tip of the steeple spire is 168 feet 7 1⁄4 inches (51.391 m) above the ground.

The State House was built between 1732 and 1753, designed by Edmund Woolley and Andrew Hamilton, and built by Woolley. Its construction was commissioned by the Pennsylvania colonial legislature which paid for construction as funds were available, so it was finished piecemeal.[8] It was initially inhabited by the colonial government of Pennsylvania as its State House, from 1732 to 1799.[4]

In 1752, when Isaac Norris was selecting a man to build the first clock for the State House, today known as Independence Hall, he chose Thomas Stretch, the son of Peter Stretch his old friend and fellow council member, to do the job.[9]

In 1753 Stretch erected a giant clock at the building's west end that resembled a tall clock (grandfather clock). The 40-foot-tall (12 m) limestone base was capped with a 14-foot (4.3 m) wooden case surrounding the clock's face, which was carved by Samuel Harding. The giant clock was removed about 1830.[10] The clock's dials were mounted at the east and west ends of the main building connected by rods to the clock movement in the middle of the building.[11] A new clock was designed and installed by Isaiah Lukens in 1828. The Lukens clock ran consecutively for eight days, "with four copper dials on each side that measured eight feet in diameter and clockworks that ensured sufficient power to strike the four-thousand pound bell made by John Wilbank." The Lukens clock remained in Independence Hall until 1877. [12]

The acquisition of the original clock and bell by the Pennsylvania Colonial Assembly is closely related to the acquisition of the Liberty Bell. By mid-1753, the clock had been installed in the State House attic, but six years were to elapse before Thomas Stretch received any pay for it.[13]

Demolition and reconstruction

While the shell of the central portion of the building is original, the side wings, steeple and much of the interior were reconstructed. In 1781, the Pennsylvania Assembly had the wooden steeple removed from the main building. The steeple had rotted and weakened to a dangerous extent by 1773, but it wasn't until 1781 that the Assembly had it removed and had the brick tower covered with a hipped roof.[14] A more elaborate steeple, designed by William Strickland, was added in 1828.

The original wings and hyphens were demolished and replaced in 1812. In 1898, these were in turn demolished and replaced with reconstructions of the original wings.

The building was renovated numerous times in the 19th and 20th century. The current interior is a mid-20th-century reconstruction by the National Park Service with the public rooms restored to their 18th-century appearance.

During the summer of 1973 a replica of the Thomas Stretch clock was restored to Independence Hall.[10]

The second-floor Governor's Council Chamber, furnished with important examples of the era by the National Park Service, includes a musical tall case clock made by Peter Stretch, c. 1740, one of the most prominent clockmakers in early America and father of Thomas Stretch.[15]

Two smaller buildings adjoin the wings of Independence Hall: Old City Hall to the east, and Congress Hall to the west. These three buildings are together on a city block known as Independence Square, along with Philosophical Hall, the original home of the American Philosophical Society. Since its construction in the mid-20th century, to the north has been Independence Mall, which includes the current home of the Liberty Bell.

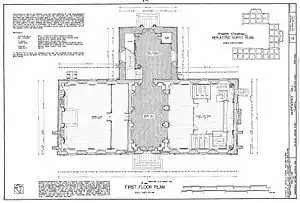

Interior layout

1 2 3 4 | ||||||||||

| Ground floor of Independence Hall (right-click links below for room images)

| ||||||||||

Liberty Bell

The lowest chamber of the original wooden steeple was the first home of the Liberty Bell. When that steeple was removed in the 1780s the bell was lowered into the highest chamber of the brick tower, where it remained until the 1850s. The much larger Centennial Bell, created for the United States Centennial Exposition in 1876, hangs in the cupola of the 1828 steeple. The Liberty Bell, with its distinctive crack, was displayed on the ground floor of the hall from the 1850s until 1976, and is now on display across the street in the Liberty Bell Center.

Declaration of Independence and Second Continental Congress

From May 10, 1775,[16] to 1783, the Pennsylvania State House served as the principal meeting place of the Second Continental Congress, a body of representatives from each of the thirteen British North American colonies.

On June 14, 1775, delegates of the Continental Congress nominated George Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in the Assembly Room of the Pennsylvania State House. The Congress appointed Benjamin Franklin to be the first Postmaster General of what would later become the United States Post Office Department on July 26.

The United States Declaration of Independence was approved there on July 4, 1776, and the Declaration was read aloud to the public in the area now known as Independence Square. This document unified the colonies in North America who declared themselves independent of the Kingdom of Great Britain and explained their justifications for doing so. These historic events are celebrated annually with a national holiday for U.S. Independence Day.

The Congress continued to meet there until December 12, 1776,[16] after which the Congress evacuated Philadelphia. During the British occupation of Philadelphia, the Continental Congress met in Baltimore, Maryland (December 20, 1776 to February 27, 1777). The Congress returned to Philadelphia from March 4, 1777 to September 18, 1777.[16]

In September 1777, the British Army again arrived to occupy Philadelphia, once again forcing the Continental Congress to abandon the State House. It then met in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, for one day (September 27, 1777) and in York, Pennsylvania, for nine months (September 30, 1777 to June 27, 1778), where the Articles of Confederation were approved in November 1777. The Second Continental Congress again returned to Independence Hall, for its final meetings, from July 2, 1778 to March 1, 1781.[16]

Under the Articles of Confederation, the Congress of the Confederation initially met in Independence Hall, from March 1, 1781 to June 21, 1783.[lower-alpha 1] However, as a result of the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, Congress again moved from Philadelphia in June 1783 to Princeton, New Jersey, and eventually to other cities.[16]

U.S. Constitutional Convention

In September 1786, commissioners from five states met in the Annapolis Convention to discuss adjustments to the Articles of Confederation that would improve commerce. They invited state representatives to convene in Philadelphia to discuss improvements to the federal government. After debate, the Congress of the Confederation endorsed the plan to revise the Articles of Confederation on February 21, 1787. Twelve states, Rhode Island being the exception, accepted this invitation and sent delegates to convene in June 1787 at Independence Hall.

The resolution calling the Convention specified its purpose as proposing amendments to the Articles, but the Convention decided to propose a rewritten Constitution. The Philadelphia Convention voted to keep deliberations secret, and to keep the Hall's windows shut throughout the hot summer. The result was the drafting of a new fundamental government design. On September 17, 1787, the Constitution was completed, and took effect on March 4, 1789, when the new Congress met for the first time in New York's Federal Hall.

Article One, Section Eight, of the United States Constitution granted Congress the authority to create a federal district to serve as the national capital. Following the ratification of the Constitution, the Congress, while meeting in New York, passed the Residence Act of 1790, which established the District of Columbia as the new federal capital. However, a representative from Pennsylvania, Robert Morris, did manage to convince Congress to return to Philadelphia while the new permanent capital was being built. As a result, the Residence Act also declared Philadelphia to be the temporary capital for a period of ten years. The Congress moved back into Philadelphia on December 6, 1790, and met at Congress Hall, adjacent to Independence Hall until moving to Washington, D.C., in 1800.

Funerary procession of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln's funeral train was to take the body of the president (and the disinterred coffin of his son Willie, who had predeceased him in 1862) from Washington, D.C., back to Springfield, Illinois, for burial. It would essentially retrace the 1,654-mile route Mr. Lincoln had traveled as president-elect in 1861 (with the deletion of Pittsburgh and Cincinnati and the addition of Chicago). The train left Washington for Baltimore at 8:00 am on April 21, 1865.[17]

Lincoln's funeral train (the "Lincoln Special") left Harrisburg on Saturday, April 22, 1865, at 11:15 am and arrived at Philadelphia at Broad Street Station that afternoon at 4:30 pm. It was carried by hearse past a crowd of 85,000 people and was held in state in the Assembly Room in the east wing of Independence Hall. While there, it was escorted and guarded by a detail of 27 naval and military officers.[18] That evening, a private viewing was arranged for honored guests of the mourners. The next day, (Sunday, April 23, 1865) lines began forming at 5:00 am. Over 300,000 mourners viewed the body – some waiting 5 hours just to see him. The Lincoln Special left Philadelphia's Kensington Station for New York City the next morning (Monday, April 24, 1865) at 4:00 am.[17][19]

League to Enforce Peace

The symbolic use of the hall was illustrated on June 17, 1915, where the League to Enforce Peace was formed here with former President William Howard Taft presiding. They proposed an international governing body under which participating nations would commit to "jointly...use...their economic and military forces against any one of their number making war against another" and "to formulate and codify rules of international law".[20]

Preservation

The original steeple was demolished in 1781 due to structural problems. The wings and hyphens were demolished in 1812 and replaced by larger buildings designed by Robert Mills and a new, more elaborate steeple designed by William Strickland constructed in 1828. The north entrance was also rebuilt during this period.

From 1802 to 1826–1827, artist Charles Willson Peale housed his museum of natural history specimens (including the skeleton of a mastodon) and portraits of famous Americans, on the second floor of the Old State House and in the Assembly Room.[21][22]

In early 1816, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania sold the State House to the City of Philadelphia, with a contract signed by the governor.[4] The deed, however, was not transferred until more than two years later. Philadelphia has owned the State House and its associated buildings and grounds since that time.[4]

In 1898, the Mills wings were removed and replaced with replicas of the originals, but the Strickland steeple was left in place.

In 1948, the building's interior was restored to its original appearance. Independence National Historical Park was established by the 80th U.S. Congress later that year to preserve historical sites associated with the American Revolution. Independence National Historical Park comprises a landscaped area of four city blocks, as well as outlying sites that include: Independence Square, Carpenters' Hall (meeting place of the First Continental Congress), the site of Benjamin Franklin's home, the reconstructed Graff House (where Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence), City Tavern (center of Revolutionary War activities), restored period residences, and several early banks. The park also holds the Liberty Bell, Franklin's desk, the Syng inkstand, a portrait gallery, gardens, and libraries. A product of extensive documentary research and archaeology by the federal government, the restoration of Independence Hall and other buildings in the park set standards for other historic preservation and stimulated rejuvenation of old Philadelphia. The site, administered by the National Park Service, is listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO (joining only three other U.S. man-made monuments still in use, the others being the Statue of Liberty, Pueblo de Taos, and the combined site of the University of Virginia and Monticello).

Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell are now protected in a secure zone with entry at security screening buildings.[23] Following the September 11, 2001 attacks, as part of a national effort to safeguard historical monuments by the United States Department of Homeland Security, pedestrian traffic around Independence Square and part of Independence Mall was restricted by temporary bicycle barriers and park rangers. In 2006, the National Park Service proposed installing a seven-foot security fence around Independence Hall and bisecting Independence Square, a plan that met with opposition from Philadelphia city officials, Pennsylvania Governor Ed Rendell, and Senator Arlen Specter.[24] As of January 2007, the National Park Service plan was revised to eliminate the fence in favor of movable bollards and chains, and also to remove at least some of the temporary barriers to pedestrians and visitors.[25][26]

Legacy

The 1989 film A More Perfect Union, which portrays the events of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, was largely filmed in Independence Hall.

Because of its symbolic history, Independence Hall has been used in more recent times as a venue for speeches and protests[27] in support of democratic and civil rights movements. On October 26, 1918, Tomáš Masaryk proclaimed the independence of Czechoslovakia on the steps of Independence Hall. National Freedom Day, which commemorates the struggles of African Americans for equality and justice, has been celebrated at Independence Hall since 1942.[28] On Independence Day, July 4, 1962, President John F. Kennedy gave an address there.[29]

Annual demonstrations organized by the East Coast Homophile Organizations advocating for gay rights were held in front of Independence Hall each July 4 from 1965 to 1969.[30][31]

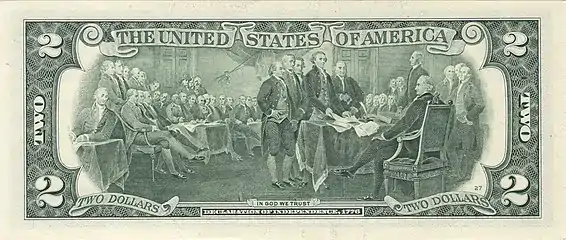

Independence Hall is pictured on the back of the U.S. $100 bill, as well as the bicentennial Kennedy half dollar. The Assembly Room is pictured on the reverse of the U.S. two-dollar bill, from the original painting by John Trumbull entitled Declaration of Independence.

1956 U.S. postal stamp

1956 U.S. postal stamp 1974 U.S. postal stamp

1974 U.S. postal stamp Reverse of the 1975-1976 Kennedy half dollar

Reverse of the 1975-1976 Kennedy half dollar U.S. $2 bill.

U.S. $2 bill. 2006 U.S. $100 bill.

2006 U.S. $100 bill.

Replicas

Independence Hall served as the model for the Pennsylvania Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, the Pennsylvania Building at the 1907 Jamestown Exposition,[32] and the Pennsylvania Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair.[33] Dozens of structures replicating or loosely inspired by Independence Hall's iconic design have been built elsewhere in the United States.

See also

- United States Declaration of Independence

- Liberty Bell

- Syng inkstand

- American Revolution

- Old City Hall, meeting place of the Supreme Court

- Declaration of Independence, 1819 John Trumbull painting

- Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, 1940 Howard Chandler Christy painting

Notes

- During this time period, American diplomats were negotiating the terms of peace with the Great Britain. See: Peace of Paris (1783)#Treaty with the United States of America. Based on preliminary articles made on November 30, 1782, and approved by the Congress of the Confederation on April 15, 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, and ratified by Congress on January 14, 1784, formally ending the American Revolutionary War between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the thirteen former colonies which on July 4, 1776, had formed the United States of America.

References

- "Management Documents". National Park Service. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Independence Hall". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- "Independence Hall". World Heritage Committee. Independence Hall's History. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- Browning, Charles H. (1916). "The State House Yard, and Who Owned It First after William Penn". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 40 (1): 87–89.

- Browning (1916), p. 89.

- Riley, Edward M. (1953). "The Independence Hall Group". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. American Philosophical Society. 43 (1): 7–42 [11]. doi:10.2307/1005661. JSTOR 1005661.

- "Independence Hall". Independence Hall Association. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- Frazier, Arthur H. (1974). "The Stretch Clock and its Bell at the State House". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 98: 296.

- Frazier (1974), p. 287.

- Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. Barra Foundation. 1982. pp. 98. ISBN 0393016102.

- Fox, Elizabeth (2018). "Like Clockwork: The Mechanical Ingenuity and Craftsmanship of Isaiah Lukens".

- Frazier (1974), p. 299.

- National Park Service. "Architectural Change over Time". Independence National Historical Park.

- Moss, Robert W. (2008). Historical Landmarks of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 28.

- "The Nine Capitals of the United States". United States Senate Historical Office. Retrieved June 9, 2005. Based on Fortenbaugh, Robert (1948). The Nine Capitals of the United States. York, Pennsylvania: Maple Press.

- "The Route of Abraham Lincoln's Funeral Train". Abraham Lincoln Research Site. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- "Enon M. Harris". Web Cemeteries. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- "Abraham Lincoln's Funeral Train". History Channel. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- Holt, Hamilton (1917). "The League to Enforce Peace". Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York. 7 (2): 65–69. JSTOR 1172226.

- "NPS Historical Handbook: Independence". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- Etting, Frank M. (1876). An Historical Account of the Old State House of Pennsylvania Now Known as the Hall of Independence. Boston: James R. Osgood and Co. pp. 154–165.

- Independence National Historic Park (n.d.). Independence National Historic Park (PDF) (Map). c. 1:6,000. Philadelphia: National Park Service.

- Urbina, Ian (August 9, 2006). "City Takes On U.S. in the Battle of Independence Square". The New York Times.

- Rincon, Sonia. "Independence Hall Won't Get Fence". kyw1060.com.

- kyw1060.com

- "We the People: Defining Citizenship in the Shadow of Independence Hall". Archived from the original on October 18, 2006.

- "National Freedom Day". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

- Kennedy, John F. (July 4, 1962). "Address at Independence Hall". Philadelphia – via John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

- Skiba, Bob. "Gayborhood". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

- "Gay Rights Demonstrations, Pennsylvania State Historical Marker". VisitPhilly.com.

- "Jamestown Exposition Site, Norfolk City, Virginia". National Register Special Feature May 2007. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- "Pennsylvania". 1939 New York World's Fair. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Independence Hall. |

| Library resources about Independence Hall |

- Independence National Historical Park. National Park Service official website

- Archeology at the site. National Park Service official website

- Independence Hall: International Symbol of Freedom, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan. National Park Service official website

- Independence Hall. ushistory.org. Independence Hall Association website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-1430, "Independence Hall Complex", 708 photos, 8 color transparencies, 45 measured drawings, 66 photo caption pages

- Independence Hall. World Heritage Sites official webpage. World Heritage Committee

- Independence Hall (at "Satellite View of Independence National Historical Park"). World Heritage Sites official webpage. World Heritage Committee

- Video of the Signing Room at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Interactive Flash Version of John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Unknown |

Tallest building in Pennsylvania 41 metres (135 ft) 1748-1754 |

Succeeded by Christ Church |

| Preceded by Unknown |

Tallest building in Philadelphia 41 metres (135 ft) 1748-1754 |

Succeeded by Christ Church |