John McGraw

John Joseph McGraw (April 7, 1873 – February 25, 1934), nicknamed "Little Napoleon" and "Mugsy", was a Major League Baseball (MLB) player and manager of the New York Giants. He stood 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) tall and weighed 155 pounds (70 kg). He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937. While primarily a third baseman throughout his career, he also played shortstop and the outfield in the major leagues.

| John McGraw | |||

|---|---|---|---|

McGraw in 1924 | |||

| Third baseman / Manager | |||

| Born: April 7, 1873 Truxton, New York | |||

| Died: February 25, 1934 (aged 60) New Rochelle, New York | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| August 26, 1891, for the Baltimore Orioles | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 12, 1906, for the New York Giants | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .334 | ||

| Home runs | 13 | ||

| Runs batted in | 462 | ||

| Stolen bases | 436 | ||

| Managerial record | 2,763–1,948 | ||

| Winning % | .586 | ||

| Teams | |||

As player

As manager | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Induction | 1937 | ||

| Election Method | Veterans Committee | ||

Much lauded as a player, McGraw was one of the standard-bearers of dead-ball era baseball. He was known for his quick temper and for bending the rules, but he also stood out as a great baseball mind. McGraw was a key player on the pennant-winning 1890s Baltimore Orioles, and later applied his talents and temper while a captain (playing)-manager, transitioning in 1902 to the New York Giants, for whom he became a bench manager in 1907 until his retirement in 1932.

Even with his success and fame as a player, he is best known for his managing, especially since it was with a team as popular as the New York Giants. His total of 2,763 victories in that capacity ranks second overall behind only Connie Mack; he still holds the National League record with 2,669 wins in the senior circuit.[1] McGraw is widely held to be "the best player to become a great manager" in the history of baseball.[2] McGraw also held the MLB record for most ejections by a manager (132) until Bobby Cox broke the record in 2007.

Early years

McGraw's father (whose name was also John) and his older brother Michael emigrated from Ireland in 1856. He arrived before the Civil War, and served in the Union Army. Shortly after the war, he married; and McGraw's older half-sister was born. John McGraw, Sr.'s first wife died, and he began moving around looking for work—a search that ultimately led him to Truxton, New York, in 1871, where he became a railroad worker. It was there that he married young Ellen Comerfort. The younger John McGraw, her first child, was born in Truxton on April 7, 1873.[3]

John's birth was the first of many to the family, as seven more children were born over the course of the next 12 years. The family was poor, and there was no public assistance available. John was, by later accounts, well-liked and an altar boy, and had a love of baseball from an early age. By doing odd jobs, he was able to save a dollar and send off for one of the Spalding company's cheaper baseball models, which he used to practice his pitching.[4]

Tragedy struck the family in the winter of 1885, when there was a diphtheria epidemic in the area. The disease took the lives of Ellen McGraw and four of her children, including John's older half-sister. John Sr. never fully recovered from the trauma of the deaths. Father and son argued over the time young John spent on baseball, especially since the father had to pay for broken windows. Later in 1885, after another such, he became abusive, and the son ran away to a neighbor, Mary Goddard, who ran the local hotel. She persuaded John Sr. to let his son stay in her care.[5]

During his time in Goddard's household, John attended school and took on several jobs that allowed him to save money to buy baseballs and the Spalding magazines that documented the rules changes in the rival major leagues of baseball, the National League and the American Association. He quickly became the best player on his school team. Shortly after his 16th birthday, he began playing for his town's team, the Truxton Grays, making a favorable impression on their manager, Albert "Bert" Kenney. While he could play any position, his ability to throw a big curveball made him the star pitcher. McGraw's relationship with Kenney precipitated his professional playing career.[6]

Playing career

Minor leagues

In 1890, Kenney bought a portion of the new professional baseball franchise in Olean, New York. The team was to play in the newly formed New York–Pennsylvania League. In return for this investment, he was named player/manager of the team (this was called "captain" at the time), and had the responsibility for selecting and signing players. When approached by McGraw, Kenney doubted the boy's curveball would fool professional ballplayers. Persuaded by the assurance McGraw could play any position, Kenney signed him to a contract on April 1, 1890.[7] McGraw would never return to live in Truxton, the place of his birth.[8]

Olean was located 200 miles from Truxton, and this was the farthest the youngster had ever traveled from his hometown. His debut with his new team was inauspicious and short-lived. He began the season on the bench. After two days, Kenney inserted him into the starting lineup at third base. McGraw would describe the moment of his first fielding chance decades later:

[F]or the life of me, I could not run to get it. It seemed like an age before I could get the ball in my hands and then, as I looked over to first, it seemed like the longest throw I ever had to make. The first baseman was the tallest in the league, but I threw the ball far over his head.[9]

Seven more errors in nine more chances followed that day, a debacle that McGraw would not soon forget. Both the team and McGraw remained ineffective, and he was fired by Kenney after six games, though the captain gave him $70 and wished him luck. He caught on with a team in Wellsville, New York, a team that played in the Western New York League. The level of baseball played there was the lowest of the minor leagues, and McGraw still struggled with his fielding. But during the 24 games he appeared in for the club, he hit .365, flashing a glimpse of what would later become his hitting prowess.[10]

After that first season, McGraw caught on with the offseason team of promoter and player, Alfred Lawson. McGraw joined the team in Ocala, Florida, and the team went by ship from Tampa to Havana, Cuba, where they played the local teams in what was then a Spanish colony. McGraw, who played shortstop, became a favorite of local fans, who dubbed him "el mono amarillo" (the yellow monkey), referring to McGraw's small size, speed, and the color of his team's uniforms.[11] McGraw fell in love with Cuba and returned there many times in later years.[12]

Lawson took his team to Gainesville, Florida in February 1891, and was able to convince the National League Cleveland Spiders to play against his team. McGraw hit three doubles in five times at bat, playing errorless ball at shortstop, and the reports of that came caused a number of minor league teams to seek to sign McGraw. Lawson acted as the boy's agent, and advised him to request $125 monthly and a $75 advance. The manager of the Cedar Rapids club in the Illinois–Iowa League was the first to wire the money, and McGraw signed with them. A number of other teams claimed that McGraw had also taken advance money from them (though McGraw maintained he returned it) and one even threatened legal action. This came to nothing, allowing McGraw to play with Cedar Rapids.[13]

By August, the league had financial woes but McGraw was hitting .275 and had become known as a tough shortstop. Billy Barnie, manager of the American Association's Baltimore Orioles, had heard about McGraw, and wrote to the Rockford team's Bill Gleason, a former Oriole, for a recommendation, which must have been favorable, as Barnie then wired Hank Smith, another former Oriole who was playing for Cedar Rapids, asking if there was any chance Baltimore could get McGraw. Cedar Rapids agreed to give McGraw his release, who left by rail for Baltimore. McGraw arrived at Camden Station in Baltimore on August 24, 1891, still only 18 years old, but now a major league baseball player. McGraw described his new home upon his arrival as "a dirty, dreary, ramshackle sort of place."[14] Barnie was unimpressed by the short stature of the player he had recruited unseen, but McGraw assured him, "I'm bigger than I look."[15]

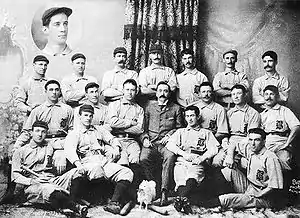

Baltimore years

During his short 1891 season with the Orioles, McGraw hit .245. Initially he played shortstop, but his poor fielding (18 errors in 86 chances) caused Barnie, who quit before the end of the season, to try him at other positions.[16] Despite his poor fielding percentage, McGraw was quickly signed to a contract for 1892 by club owner Harry Von der Horst. The American Association failed after the 1891 season, and the Orioles and other surviving franchises moved to an expanded twelve-team National League.[17]

Early in the 1892 season, Von der Horst hired Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder Ned Hanlon to manage the Orioles.[18] Hanlon dismissed or traded many of the players, seeking to build a winner, but in 1892, the Orioles lost over 100 games, easily finishing last. Of the 17 players he inherited, he would wind up keeping only three: pitcher Sadie McMahon, catcher Wilbert Robinson and McGraw.[19] According to Burt Solomon in his book on the Orioles teams of the 1890s, "Hanlon saw that McGraw's value to the Orioles came less from his agility than from his intensity. He never gave up and had contempt for anyone who did, John McGraw could drive his teammates to another level of play. So he was to serve as the soul of a team about to be born."[20] But little of that showed in the 1892 season, in which McGraw hit .267 with 14 stolen bases while playing a variety of positions; he was three times left behind in Baltimore during road trips as the team sought to economize on traveling expenses.[21] During the 1892–93 off season, McGraw attended Allegany College (soon to be renamed St. Bonaventure), trading his skills as a baseball coach for the right to attend without paying tuition.[22]

Hanlon's wheeling and dealing continued through 1893, seeking to secure quality ballplayers despite having little money to purchase them from other teams. He secured Hughie Jennings from the Louisville Colonels, a shortstop whose acquisition caused Hanlon to displace McGraw from that position.[23] The team finished eighth in 1893,[24] while McGraw hit .327, second on the club to Robinson, and led the league in runs scored. He spent a second winter at St. Bonaventure, this time with Robinson as his assistant coach and fellow student. During the offseason, McGraw narrowly avoided being dealt to the woeful Washington Senators when a trade for Duke Farrell fell through when Washington refused to pay cash in addition to giving up Farrell.[25] Deciding McGraw could handle third base, Hanlon made a major trade with the Brooklyn Dodgers, sending infielder Billy Shindle and George Treadway, receiving in return five-time batting champion Dan Brouthers and diminutive outfielder Willie Keeler.[26]

The Orioles' 1894 spring training took place in Macon, Georgia, where Hanlon taught the players innovative plays that he had thought of during his playing career, and in the evening, drilled them on baseball's rules and possible ways of taking advantage of them.[27] The innovations of the Orioles of the mid-1890s would include the Baltimore chop, hitting a pitched ball so it would bounce high and allow the batter to reach first base safely, and having the pitcher cover first base when the first baseman fielded a ball that took him away from the base, and though they probably did not invent the hit and run, they were the first team to employ it as a regular maneuver.[28] McGraw often took the lead in the discussions. When the team played in New Orleans, a local sportswriter called him "a fine ball-player, yet he adopts every low and contemptible method that his erratic brain can conceive to win a play by a dirty trick".[29] This included shoving, holding, and blocking baserunners,[29] at a time when there was often only a single umpire. One baserunner, anticipating that McGraw would hold him by the belt, loosened it and when he broke for home, McGraw was left holding the belt in his hand as the runner scored.[30][31]

—Cait N. Murphy (2007). Crazy '08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History, p. 18

McGraw usually batted leadoff for the 1894 Orioles,[32] and was a sparkplug for the team, batting .340 and stealing 78 bases, second in the league. He would foul off pitch after pitch—a valuable talent in the pre-1901 era in which foul balls generally did not count as strikes—and, with Keeler, "elevated into an art form" the hit and run.[33] Many of the players, including McGraw, lived in the same Baltimore boarding house, and talked baseball deep into the night. From such discussions arose the discovery that a runner on third had an excellent chance of scoring if he left at the pitcher's first motion and the batter bunted, originating the squeeze play.[34] The Orioles won 18 in a row into September to give them enough breathing room to win their first pennant over the New York Giants and the Boston Beaneaters. Amid disputes over money, they lost the postseason Temple Cup series to the second-place Giants.[35] After a brief visit to Truxton, McGraw spent the winter at St. Bonaventure.[36]

The Orioles' "Big Four" (McGraw, Jennings, Keeler and Joe Kelley) held out to start 1895, but came to terms with the club in time for spring training.[37] By 1895, McGraw had become controversial for his aggressive style of play, master of such tactics as trying to knock the ball from the gloves of fielders and noted for verbally abusing opponents and umpires in the pursuit of victory. Some writers urged Hanlon to rein him in, but others argued that fans were flocking to the ballpark to see such play. The league responded by increasing the fines to be imposed on players for misconduct.[38] In spite of the controversy, the Orioles won their second consecutive pennant, though they lost the Temple Cup again, this time to the Cleveland Spiders.[39] McGraw, suffering from malaria, missed part of the season,[40] but hit .369 in 96 games, with 61 stolen base and 110 runs scored.[41] McGraw again went to St. Bonaventure, though he returned to Baltimore when the fall term ended in mid-December, stating he was exhausted and leaving the coaching to Jennings.[42]

During 1896 spring training, McGraw fell ill with typhoid fever in Atlanta, and was hospitalized for two months there, spending much of the summer convalescing. By the time he was ready to play, in late August, the Orioles were well ahead in the pennant race, which they won easily, this time winning the Temple Cup over the Spiders in four straight games.[43] McGraw appeared in only 23 games for Baltimore, batting .325.[41] After the season, the Orioles had planned an exhibition tour of Europe, but it was cancelled over concerns poor weather would preclude too many games. The Big Four went anyway, visiting Britain, Belgium and France. Following their return, in February 1897, McGraw married Minnie Doyle, whose father was a city official. McGraw and the Orioles both had seasons that disappointed them in 1897, with McGraw hitting .325, and the team plagued by injuries as Baltimore lost the pennant to the Boston Beaneaters, though the Orioles won the final iteration of the Temple Cup.[44] In 1898, McGraw hit .342, but the Orioles finished second again, six games behind the Beaneaters.[45]

The Orioles' success on the field had not translated to increased attendance, which fell substantially as the Orioles won pennants; the violence on the field spread into the stands and respectable people avoided attending their games. Across the league, attendance became stagnant even as baseball increased in popularity nationwide.[46] The Spanish–American War of 1898 distracted the public from baseball, causing financial problems for the teams.[47] Before the 1899 season, Van der Horst and Hanlon (a co-owner) bought a half-interest in the Dodgers, while Brooklyn owners, led by Charlie Ebbets, bought a half interest in the Orioles. Brooklyn drew better attendance than Baltimore, and under the arrangement, known as "syndicate baseball", manager Hanlon and the better Oriole players would move to Brooklyn. McGraw and Robinson, who had financial interests in Baltimore, refused to go and before the 1899 season, McGraw was made player-manager of the Orioles.[48]

McGraw schooled his players in the Orioles system, and led by example, hitting .391 for the season. To Hanlon's surprise, attendance in Baltimore rebounded, and the Orioles remained close to Brooklyn in the pennant race through late August, when McGraw had to leave the team due to the illness of his wife. By the time he returned, after her death, Brooklyn had clinched the pennant; the Orioles finished fourth.[49] Nevertheless, for getting the castoff Orioles to perform so well amid his personal tragedy, McGraw was hailed as a managerial genius in the newspapers, and pennant-winning manager Hanlon was compared unfavorably to him.[50]

St. Louis and American League Orioles

Syndicate baseball was insufficient to revive the finances of the National League, and amid rumors that the league would contract from 12 to 8 teams, with Baltimore among the franchises to be ended, McGraw was among those seeking to revive the rival American Association. Although he secured a lease on the Orioles' home field, Union Park, the new league died at birth, four NL teams (including Baltimore) were ended, and McGraw and Robinson were sold to the St. Louis Cardinals. They did not report until the season had begun, having secured increases in salary and a concession that their contracts would not contain the then-standard reserve clause which bound them to the signing team for the following season. Thus, they would be free agents after the 1900 season.[51] Injured for part of the season, McGraw hit .337 in 98 games as the Cardinals finished tied for fifth, but when manager Patsy Tebeau resigned in August, McGraw ruled out replacing him.[52]

Ban Johnson, president of the minor league Western League, sought to build a second major league, which would seek to attract the fans with baseball without rowdyism, where the rules would be respected and aggression towards umpires not tolerated. McGraw and Robinson, centerpieces of the old Orioles where such aggression was just another tactic towards victory, were an odd fit in such a grouping, but as Johnson renamed his circuit the American League (AL) and sought to put franchises in abandoned NL cities like Baltimore, Washington and Cleveland, they became key to his plans. He was confident he could control them, since one of the requirements was that franchises grant the league an option to buy a majority stake and thus take them over if necessary.[53]

Even while under contract to the Cardinals, McGraw and Robinson were involved in meetings aimed at upgrading the Western League to major league status, and on November 12, 1900, they signed an agreement with Johnson giving them exclusive rights to form an AL franchise in Baltimore, thereafter securing financial backing from a number of local figures. He spent much of the winter traveling and seeking to sign players. Among them was Charley Grant, an African-American second baseman who McGraw alleged was a Native American, but Charles Comiskey, owner of the AL Chicago White Sox, was undeceived, thus ending McGraw's only attempt to break the baseball color line—McGraw, like many of the time who grew up in the rural North, had no strong views about African Americans, but sought to sign a talented ballplayer.[54]

McGraw batted leadoff and managed the Orioles as Major League Baseball made its return to Baltimore in 1901, but found his playing time limited by injuries and a suspension by Johnson for abusing the umpire. The Orioles finished fifth, with McGraw batting .349 in 73 games. The team lost money.[55] On January 8, 1902, McGraw married for the second time, to Blanche Sindall, whose father was a Baltimore housing contractor.[56]

McGraw's playing time diminished as he played for the American League Baltimore Orioles (1901–1902), and the New York Giants (1902–1906). 1902 was his last season as a full-time player; he never played in more than 12 games or tallied more than 12 at bats in any season thereafter. He retired having accumulated 1,024 runs, 13 home runs, 462 RBI, a .334 batting average and a .466 on-base percentage. His .466 career on-base percentage remains third all-time behind only baseball legends Ted Williams (.482) and Babe Ruth (.474).

Style of play

When, as a young player, McGraw tried to block Cleveland's Buck Ewing from third base, Ewing "went into him with such force that he knocked McGraw off his feet", John B. Foster of The Cleveland Leader wrote. "McGraw is rather a light youngster to be so anxious to block men off the bases. Another year in the league is likely to teach him a sorry lesson."[57]

Former Baltimore teammate Sadie McMahon said in 1948, "McGraw wouldn't give the bag to the base runner like they do today" and also that he would "stand on the inside corner and make the runner go around."[59]

In his 1998 The League That Failed, David Voigt said McGraw believed that "only by mastering the rules could he circumvent them." So "he became a master at finding loopholes."[60] Voigt added, "Among tactics used by McGraw was the opportunistic base runner's trick of slapping a ball from an infielder's grasp, the psychological ploy of wearing wickedly sharpened spikes, and vocally abusing opposing players and umpires."[61]

Voigt also wrote that McGraw had a reputation as a "dirty player" as of 1895 that was "the talk of the league." By 1895, some were singling out McGraw for his mouth."[62]

In 1899, the Pittsburg Leader said the following after he was "as quiet as a lamb" one day at Pittsburgh: "McGraw, although having the reputation of being a rowdy ball player, has never shown any rowdy tactics in this city."[63]

McGraw figures prominently in an Orioles-spiked-umpires recollection in Fred Lieb's 1950 The Baseball Story, which quotes 1890s umpire John Heydler, later a National League president, as saying: "We hear much of the glories and durability of the old Orioles, but the truth about this team seldom has been told. They were mean, vicious, ready at any time to maim a rival player or an umpire, if it helped their cause. The things they would say to an umpire were unbelievably vile, and they broke the spirits of some fine men. I've seen umpires bathe their feet by the hour after McGraw and others spiked them through their shoes. The club never was a constructive force in the game. The worst of it was they got by with much of their browbeating and hooliganism. Other clubs patterned after them, and I feel the lot of the umpire never was worse than in the years when the Orioles were flying high."[64]

Statistics

| Year | Age | Team | Lg | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | SO | BA | OBP | SLG | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1891 | 18 | Baltimore Orioles | AA | 33 | 115 | 17 | 31 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 14 | 4 | 17 | .270 | .359 | .383 | .741 |

| 1892 | 19 | Baltimore Orioles | NL | 79 | 286 | 41 | 77 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 26 | 15 | 21 | .269 | .355 | .339 | .694 |

| 1893 | 20 | Baltimore Orioles | NL | 127 | 480 | 123 | 154 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 64 | 38 | 11 | .321 | .454 | .413 | .866 |

| 1894 | 21 | Baltimore Orioles | NL | 124 | 512 | 156 | 174 | 18 | 14 | 1 | 92 | 78 | 12 | .340 | .451 | .436 | .887 |

| 1895 | 22 | Baltimore Orioles | NL | 96 | 388 | 110 | 143 | 13 | 6 | 2 | 48 | 61 | 9 | .369 | .459 | .448 | .908 |

| 1896 | 23 | Baltimore Orioles | NL | 23 | 77 | 20 | 25 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 13 | 4 | .325 | .422 | .403 | .825 |

| 1897 | 24 | Baltimore Orioles | NL | 106 | 391 | 90 | 127 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 48 | 44 | 15 | .325 | .471 | .379 | .849 |

| 1898 | 25 | Baltimore Orioles | NL | 143 | 515 | 143 | 176 | 8 | 10 | 0 | 53 | 43 | 13 | .342 | .475 | .396 | .871 |

| 1899 | 26 | Baltimore Orioles | NL | 117 | 399 | 140 | 156 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 33 | 73 | 21 | .391 | .547 | .446 | .994 |

| 1900 | 27 | St. Louis Cardinals | NL | 99 | 334 | 84 | 115 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 33 | 29 | 9 | .344 | .505 | .416 | .921 |

| 1901 | 28 | Baltimore Orioles | AL | 73 | 232 | 71 | 81 | 14 | 9 | 0 | 28 | 24 | 6 | .349 | .508 | .487 | .995 |

| 1902 | 29 | Baltimore Orioles/New York Giants | AL/NL | 55 | 170 | 27 | 43 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 12 | 17 | .253 | .420 | .312 | .732 |

| 1903 | 30 | New York Giants | NL | 12 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | .273 | .467 | .273 | .739 |

| 1904 | 31 | New York Giants | NL | 5 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .333 | .467 | .333 | .800 |

| 1905 | 32 | New York Giants | NL | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 1906 | 33 | New York Giants | NL | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .000 | .333 | .000 | .333 |

Manager of the New York Giants (1902—1932)

Hiring

McGraw started the 1902 season injured, and between recovering from a knee injury, suspensions, and a deep cut from the sharpened spikes of a baserunner, played few games for the Orioles. The team drifted between fifth and seventh in the league, and there was widespread talk that at the end of the season, Johnson would shift the team to New York.[65] Although being a manager and part owner of a New York AL team would be a major opportunity for him, McGraw was convinced Johnson planned to discard him in the process.[66] According to Solomon, "so McGraw struck first. Any true Oriole would."[67] Baseball author Maury Klein wrote, "While the events that followed seem clear in retrospect, the question of who devised which parts of the outcome remains an intriguing mystery."[68]

On June 18, 1902, with the Orioles on a western road trip with Robinson as acting manager, McGraw (who was recuperating from the spiking) traveled to New York and met with Andrew Freedman, owner of the Giants. The two came up with a scheme not only for McGraw to switch leagues but to cripple the Orioles and possibly the AL. When McGraw returned to the lineup on June 28, he provoked the umpire into kicking him out of the game and, when he refused to go, forfeiting the game to Boston. This resulted in his indefinite suspension by Johnson.[69]

McGraw went to the directors of the Baltimore franchise, and demanded that either they reimburse the $7,000 he had advanced towards player salaries or that they release him.[67] The team agreed to his release on July 8, and McGraw sold his interest in the club to John Mahon, a team official and Joe Kelley's father in law. McGraw immediately announced he would sign to manage the Giants, which he did the next day. His salary of $11,000 was the largest of any player or manager in baseball history to that point.[70][71]

Freedman then secured a controlling interest in the Orioles from Mahon, Kelley and others. Once he had done so, he directed the release of Orioles Joe McGinnity, Dan McGann, Roger Bresnahan and Jack Cronin, all of whom promptly signed with the Giants. Cincinnati Reds owner John T. Brush was in on the deal; he signed Kelley as manager and also outfielder Cy Seymour, both released by the Orioles. Baltimore was left with so few players it had to forfeit its next game; the crisis might have destroyed the American League had not Johnson acted decisively to take over the Baltimore franchise, getting the other seven teams to contribute players to the Orioles, who finished last.[72] After the season, the two leagues signed a peace agreement, and the AL replaced the Baltimore franchise with one in New York City.[73] That team became known as the Highlanders and later as the New York Yankees.[74]

According to McGraw biographer Charles C. Alexander, given a crisis in his professional life as Johnson sought to exclude him from the Orioles' move to New York, McGraw acted in a way that was "totally ruthless and unscrupulous".[75] Baseball historian Fred Lieb, who knew both men well, wrote that McGraw and Johnson never spoke again.[75]

Early years (1902–1908)

By the time the Giants returned from a road trip to meet McGraw at their home field, the Polo Grounds, they had a record of 22–50 and were in last place in the NL. Not all of them got to return, McGraw released four of them by telegraph to Cincinnati, and two more when they returned to New York. McGraw played occasionally, and spent part of the summer appearing in AL cities seeking to sign players, much to the discomfiture of the local team's management. The Giants finished last, and at the end of the season, Freedman sold the team to Brush (who had vended his interest in the Reds). With his knee injury robbing him of much of his skill,[76] McGraw batted .286 in 20 games with Baltimore and .234 in 35 games with the Giants. He would never again be an everyday player.[41]

McGraw's knee gave way in 1903 spring training, confirming he would play few games; he was also injured early in the year by a ball thrown by pitcher Dummy Taylor that broke McGraw's nose. The cartilage did not heal properly, contributing to respiratory problems that plagued McGraw for the rest of his life. During spring training, McGraw took pains to cultivate the team's star, pitcher Christy Mathewson, and the two men (with their wives, Blanche McGraw and Jane Mathewson) became so close that they shared an apartment in New York City.[77] McGraw also forged a strong relationship with the new Giants owner, Brush, according to baseball author Cait N. Murphy, "the partnership clicked: Brush signed the checks and did as McGraw ordered".[78]

McGraw's new-look Giants got off to a hot start in 1903, and were in first place ahead of the two-time defending NL champion Pittsburgh Pirates at the end of May, as crowds not seen in a decade flocked to the Polo Grounds. Still coming together as a team, they thereafter faded and finished second, 61/2 games behind the Pirates, but McGinnity won 31 games while Mathewson won 30 and led the league in strikeouts.[79] As a player, McGraw appeared in 11 games and batted .273.[41] The Giants' success, and the controversy the belligerent McGraw aroused, meant they attracted larger crowds not only at the Polo Grounds, but on the road as well.[80] Leading the most hated team in the league, McGraw stated, "it is the prospect of a hot feud, that brings out the crowd."[81]

Before the 1904 season, McGraw deemed his team the strongest he had ever led, and predicted the Giants would win the pennant. The team played accordingly, and opened up a 15 game lead on the Chicago Cubs by the start of September. With the Highlanders leading the AL for much of the year (though they ultimately were defeated by Boston), there was intense pressure on McGraw and Brush to agree to a postseason series against the AL champions, what would later come to be known as the World Series, like the Pirates had the previous year. Both men refused, with McGraw stating that there was nothing in the league rules requiring its champions to play a series against "a victorious club in a minor league".[82] According to Alexander, both men disliked Ban Johnson and feared losing the series to the AL champs, as the Pirates had in 1903. The Giants won the pennant, setting a major league record for victories (to that point) with 106.[83]

McGraw continued building his team in the 1904–1905 offseason, purchasing Sammy Strang from Brooklyn. In addition to playing nearly every position, Strang pioneered a McGraw innovation, the pinch hitter.[84] He schooled them in the aggressive techniques of the old Orioles, stating years later, “It was a team of fighters. They thought they could beat anybody and they generally could."[85] The team was never really threatened in its drive to a second consecutive pennant, and McGraw always stated this was the best team he ever managed. It won 105 games, finishing nine games ahead of the Pirates.[86] McGraw was ejected from games 13 times, a personal record,[87] and Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss sought to have McGraw disciplined after the manager shouted accusations at him after one ejection. The league Board of Directors refused to suspend McGraw, and when NL president Harry Pulliam suspended McGraw for 15 games for accusing Pulliam of being Dreyfuss's lackey, the suspension was overturned by a court.[88] This time, the Giants had no objection to playing a postseason series against the AL champions, the Philadelphia Athletics, managed by Connie Mack; Brush had served on the committee that formulated the rules for the interleague matchup. The 1905 World Series saw the greatest exhibition of pitching of any postseason series, as every game ended in a shutout, three of them pitched by Mathewson and one by McGinnity, as the Giants won, four game to one, with the Athletics winning only Game Two, in which Chief Bender did not allow a run. Among the shower of rewards that fell from the hands of Brush was a new contract for McGraw, at $15,000 per year.[89] The victory made the Giants heroes in a city that always admired winners, and McGraw one of the most prominent people in New York.[90]

Confident of a third-straight NL championship, McGraw put "World's Champions" on the front of his team's uniforms. But the drive for that was slowed by Mathewson getting diphtheria, and outfielder Mike Donlin broke a leg;[87] Bresnahan and McGann also sustained injuries.[91] Even a healthy team would have been hard-pressed to keep up with the 1906 Cubs, though, who went 116-36.[92] The Giants finished second, twenty games behind.[87] McGraw spent twenty days suspended, the longest of his career, after being ejected after arguing an out call on a Giant at home plate in a loss to Chicago at the Polo Grounds on August 6.[93] He also played the last games of his playing career, going hitless in two plate appearances in the four games he played.[41]

Believing the Cubs would fall back, McGraw made few changes for the 1907 Giants. But after both teams got off to hot starts, the Cubs swept the Giants in Chicago and by mid-July had pulled away as the Giants fell back, with New York finishing in fourth place, 251/2 games behind. Mathewson won 24 games but other pitchers posted mediocre performances.[94] McGraw later stated, "It was in 1907 that I discovered my players were growing old and beginning to slip, Always I have made it a point never to let a club grow old on me. A manager must start reconstruction quickly or several years will be required to bring a ball club back."[95] Less combative than usual towards the umpires, McGraw spent much time in the final weeks of the season at the racetrack, seemingly uninterested in his team, and spoke of possible retirement from baseball.[87][96]

The 1908 season has been deemed the most remarkable in baseball history.[97] Seeking to retool his team for another set of championship seasons, McGraw brought an unusual number of rookies to spring training in Marlin, Texas to train alongside the remaining veterans such as Mathewson. Few expected the Giants to challenge the Cubs—Pittsburgh was expected to be Chicago's main competition—but McGraw had confidence in his team. The Giants won consistency; in early July only a game and a half separated the Cubs, Giants and Pirates.[98] The crucial game of the season was on September 23, with the Giants hosting and a game ahead of the Cubs. With the score tied 1–1 in the ninth inning, two outs, Harry McCormick on third base, and rookie Fred Merkle on first, Al Bridwell lined a ball cleanly into center field, and McCormick trotted home with the apparent winning run. Merkle, though, did not touch second base, but headed for the clubhouse. This was not unusual at the time, but as the happy crowd took the field, Chicago second baseman Johnny Evers recovered the ball and stepped on second base. The umpires ruled Merkle out, and the game a tie.[99]

The game immediately became the subject of front page headlines and intense public debate.[100] The schedule ended with the Giants and Cubs tied for first, and the NL ordered the September 23 game replayed. McGraw was furious, believing his team by rights had already won the pennant, and told his players he would back them if they chose not to play, but after meeting with Brush, they chose to.[101] There was so much attention focused on that single game that it eclipsed the presidential race between William Howard Taft and William Jennings Bryan.[102] Before a crowd of as many as 40,000, plus many more outside the stadium, the Giants lost the game and the pennant, 4–2. After the game, Merkle, who had been dubbed "Bonehead" and had taken the controversy hard, came to McGraw and asked to be released or traded. Instead, McGraw praised Merkle's gameness through the controversy and urged him to put the incident behind him. When Merkle received his 1909 contract, he found McGraw had given him a raise of $300.[103]

1899–1932

_(LOC).jpg.webp)

Despite great success as a player, McGraw is most remembered for his tremendous accomplishments as a manager. In his book The Old Ball Game, National Public Radio's Frank Deford calls McGraw "the model for the classic American coach—a male version of the whore with a heart of gold—a tough, flinty so-and-so who was field-smart, a man's man his players came to love despite themselves."[104] McGraw took chances on players, signing some who had been discarded by other teams, often getting a few more good seasons out of them. Sometimes these risks paid off; other times, they did not work out quite so well. McGraw took a risk in signing famed athlete Jim Thorpe in 1913. Alas, Thorpe was a bust, not because he lacked athletic ability, but because "he couldn't hit a ball that curved."[104] McGraw was one of the first to use a relief pitcher to save games. He pitched Claude Elliott in relief eight times in his ten appearances in 1905. Though saves were not an official statistic until 1969, Elliot was retroactively credited with six saves that season, a record at that time.[105][106]

McGraw believed that he had to eliminate any potential distractions that could cause his teams to lose. For example, Casey Stengel, who played for the Giants from 1921 to 1923, recalled that McGraw would go over the meal tickets at the team hotel, and wasn't shy about telling his players that they weren't eating right. For most of his tenure, he set a curfew for 11:30 pm. According to Rogers Hornsby, who served as a player-coach for the Giants in 1927, either McGraw or one of his coaches would knock on the players' hotel room doors at 11:30 sharp—and someone was expected to answer. He was known to be extremely competitive; he would fine players for fraternizing with members of other teams and would not tolerate smiling in the dugout. According to Bill James, with McGraw "the rules were well understood."[107]

Over 33 years as a manager with the Baltimore Orioles of both leagues (1899 NL, 1901–1902 AL) and New York Giants (1902–1932), McGraw compiled 2,763 wins and 1,948 losses for a .586 winning percentage. His teams won 10 National League pennants and three World Series championships, and they had 11 second-place finishes while posting only two losing records. In 1918, he broke Fred Clarke's major league record of 1,670 career victories; he was later passed by Mack. McGraw led the Giants to first place each year from 1921 to 1924, becoming the only National League manager to win four consecutive pennants. At the time of his retirement, McGraw had been ejected from games 131 times (at least 14 of these came as a player). This record would stand until Atlanta Braves manager Bobby Cox broke it on August 14, 2007.

When McGraw learned that Giants owner Harry Hempstead and other heirs of Hempstead's predecessor, John T. Brush, wanted out of baseball before the 1919 season, McGraw set about finding a buyer. He eventually found one in stockbroker Charles Stoneham. As part of the deal, Stoneham took McGraw on as a partner, and made him the team's vice president.[108] Stoneham also gave McGraw complete authority over the baseball side of the operation. However. McGraw had enjoyed more or less a free hand in baseball matters since his arrival. McGraw wrote an autobiography of his years in baseball, published in 1923, in which he expressed grudging respect for several opposing players.[109] McGraw managed his last game on June 1, 1932, losing 4–2 to the Philadelphia Phillies at the Polo Grounds, taking the Giants to 17–23 on the season. On June 3, he announced his resignation from the ballclub, with Bill Terry (who had served as the first baseman for the team since 1923) picked as his successor.[110][111] McGraw finished with a record of 2,583 wins and 1,948 losses with the Giants.[112] The following year, he returned to manage the National League team in the inaugural 1933 All-Star Game.

Although for most of his career McGraw wore the same baseball uniform his players wore, he eventually took a page out of Mack's book toward the end of his career and began managing in a three piece suit. He continued to do so until his retirement.

Overall record

| Team | From | To | Regular season record | Post-season record | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | W | L | Win % | G | W | L | Win % | |||

| Baltimore Orioles (NL) | 1899 | 1899 | 148 | 86 | 62 | .581 | — | |||

| Baltimore Orioles (AL) | 1901 | 1902 | 190 | 94 | 96 | .495 | — | |||

| New York Giants | 1902 | 1924 | 3249 | 1961 | 1288 | .604 | 47 | 23 | 24 | .489 |

| New York Giants | 1924 | 1925 | 94 | 55 | 39 | .585 | 7 | 3 | 4 | .429 |

| New York Giants | 1925 | 1927 | 379 | 199 | 180 | .525 | — | |||

| New York Giants | 1928 | 1932 | 651 | 368 | 283 | .565 | — | |||

| Total | 4711 | 2763 | 1948 | .586 | 54 | 26 | 28 | .481 | ||

| Ref.:[112] | ||||||||||

New York Giants managerial record

McGraw became the third of three managers for the New York Giants in 1902, and held the position until 1932.[112] He briefly stood down as manager in the middle of the 1924 season due to illness, and coach and former Orioles teammate Hughie Jennings served as interim manager.[113] Jennings spelled him again in the middle of the 1925 season.[114] He took another leave of absence during the 1927 season; player-coach Hornsby served as interim manager during this time.[115]

| From | To | Regular season record | Post–season record | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | W | L | Win % | G | W | L | Win % | ||

| 1902 | 1924 | 3249 | 1961 | 1288 | .604 | 47 | 23 | 24 | .489 |

| 1924 | 1925 | 94 | 55 | 39 | .585 | 7 | 3 | 4 | .429 |

| 1925 | 1927 | 379 | 199 | 180 | .525 | — | |||

| 1928 | 1932 | 651 | 368 | 283 | .565 | — | |||

| Total | 4373 | 2583 | 1790 | .591 | 54 | 26 | 28 | .481 | |

| Ref.:[112] | |||||||||

Personal life

McGraw married Minnie Doyle, the daughter of prominent Baltimore politician Michael Doyle, on February 3, 1897. This was at the height of his fame as a player for the old Baltimore Orioles of the National League. Two years later, while McGraw was on a road trip with his team, Minnie developed appendicitis. An emergency appendectomy was performed, and McGraw was called back from Louisville, Kentucky. Her condition worsened; and, surrounded by McGraw and other members of the family, Minnie died on September 1, 1899 at the age of 23.[116]

McGraw married his second wife, Blanche Sindall, on January 8, 1902. She outlived McGraw by nearly 30 years, dying on November 4, 1962. Even after her husband's death, Mrs. McGraw was a devoted fan of the team he had managed for so long.[117] In 1951, she threw out the first pitch during a World Series game in which her beloved Giants played the New York Yankees.[118] The Yankees won that day, 6–2, and went on to win the championship — their third in a row — in six games.

As owners of a bowling, billiards, and pool hall in Baltimore, McGraw and Wilbert Robinson introduced the sport of duckpin bowling within the city of Baltimore in 1899.

Later years

In 1923, only nine years before he retired, McGraw reflected on his life inside the game he loved in his memoir My Thirty Years in Baseball.[109] He stepped down as manager of the New York Giants in the middle of the 1932 season. He was reactivated briefly when he accepted the invitation to manage the National League team in the 1933 All-Star Game.

Less than two years after retiring, McGraw died of uremic poisoning[119] at age 60 and is interred in New Cathedral Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland.[120]

Connie Mack would surpass McGraw's major league victory total just months later. After McGraw's death, his wife found, among his personal belongings, a list of all the black players he wanted to sign over the years.[121]

Posthumous honors

McGraw was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937; his plaque stated that he was considered the greatest assessor of baseball talent. In honor of the days he spent coaching at St. Bonaventure, St. Bonaventure University named its athletic fields after McGraw and his teammate, fellow coach and fellow Hall of Famer Hugh Jennings.

Although McGraw played before numbers were worn on jerseys, the Giants honor him along with their retired numbers at Oracle Park.

The John McGraw Monument stands in his hometown of Truxton.

Works

- "The Value of Team Work," Chicago Daily Socialist, vol. 5, no. 137 (April 5, 1911), p. 4.

- My Thirty Years in Baseball. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1923.

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball managers by wins

- List of Major League Baseball player-managers

- List of St. Louis Cardinals team records

- Baltimore Orioles (19th century)

- Inside Baseball

Sources

- Alexander, Charles C. (1995). John McGraw. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-5925-6.

- Appel, Marty (2012). Pinstripe Empire: The New York Yankees From Before the Babe to After the Boss (ebook ed.). New York: Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-60819-492-6.

- Deford, Frank (2005). The Old Ball Game: How John McGraw, Christy Mathewson, and the New York Giants Created Modern Baseball (ebook ed.). Grove Press. ISBN 978-1-5558-4627-5.

- Felber, Bill (2007). A Game of Brawl: The Orioles, the Beaneaters, and the Battle for the 1897 Pennant. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1136-0.

- Klein, Maury (2016). Stealing Games: How John McGraw Transformed Baseball with the 1911 New York Giants (eBook ed.). Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-63286-026-2.

- Murphy, Cait N. (2007). Crazy '08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History. HarperCollins e-books. ISBN 978-0-06-088938-8.

- Solomon, Burt (2000) [1999]. Where They Ain't : The Fabled Life and Untimely Death of the Original Baltimore Orioles, the Team that Gave Birth to Modern Baseball (paperback ed.). Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-684-85451-9.

- Threston, Christopher (2003). The Integration of Baseball in Philadelphia. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1423-9.

- Voigt, David Quentin (1998). The League That Failed. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3309-8.

- Markoe, Arnie. The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives. ISBN 0-684-80665-7.

References

- "Manager records index". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- Baseballlibrary.com profile of McGraw Archived May 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Alexander 1995, pp. 18–19.

- Alexander 1995, p. 20.

- Klein 2016, pp. 110–111.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 23–25.

- Alexander 1995, p. 25.

- Deford 2005, p. 284.

- Alexander 1995, p. 26.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 26–27.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 28–29.

- Klein 2016, pp. 118–119.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 29–30.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 31–32.

- Klein 2016, p. 120.

- Klein 2016, p. 121.

- Alexander 1995, p. 39.

- Solomon 1998, pp. 44–45.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 45–48.

- Solomon 2000, p. 48.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 42–43.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 45–46.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 52–54.

- Voigt 1998, p. 182.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 49–51.

- Voigt 1998, pp. 182—183.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 58–60.

- Klein 2016, pp. 108–112.

- Alexander 1995, p. 52.

- Felber 2007, pp. xiii, 12.

- Deford 2005, pp. 117–118.

- Alexander 1995, p. 53.

- Klein 2016, pp. 128–130.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 70–71.

- Voigt 1998, pp. 55–57.

- Alexander 1995, p. 55.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 88–90.

- Voigt 1998, pp. 60–63.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 98–99.

- Alexander 1995, p. 60.

- Solomon 2000, p. 290.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 63–64.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 65–67.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 110–123, 290.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 77–80.

- Murphy 2007, pp. 19–20.

- Voigt 1998, pp. 81—82.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 148–149, 156.

- Voigt 1998, pp. 93–95.

- Voigt 1998, p. 96.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 179–193.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 92–93.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 199–201.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 95–97.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 206–211, 220, 290.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 105–107.

- Rosenberg. Cap Anson 3., p. 82, citing, in part, the Cleveland Leader, September 15, 1893.

- Donovan, Henry. "Chicago Eagle". Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- Rosenberg. Cap Anson 3., pp. 47-48, citing, in part, the Baltimore Sun, July 11, 1948.

- Rosenberg. Cap Anson 3., p.233, citing David Quentin Voigt, The League That Failed (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow, 1998), 61.

- Rosenberg. Cap Anson 3., p. 233, citing, in part, Voigt, The League That Failed (1998), 61.

- Rosenberg. Cap Anson 3., pp. 233-234, citing, in part, Voigt, The League That Failed (1998), 61.

- Rosenberg, Howard W. Cap Anson 3., p. 234, citing, in part, Pittsburg Leader and Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, May 23, 1899.

- Rosenberg. Cap Anson 3., p. 217, citing, in part, Frederick G. Lieb, The Baseball Story (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1950), 141.

- Solomon 2000, pp. 226–227.

- Alexander 1995, p. 113.

- Solomon 2000, p. 227.

- Klein 2016, p. 193.

- Alexander 1995, p. 114.

- Alexander 1995, p. 115.

- Solomon 2000, p. 221.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 116–117.

- Appel 2012, pp. 82–83.

- Calcaterra, Craig (April 10, 2020). "Today in Baseball History: the Yankees become the Yankees". NBC Sports. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- Alexander 1995, p. 117.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 121–124.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 127–129.

- Murphy 2007, pp. 26–27.

- Klein 2016, pp. 241–242.

- Klein 2016, pp. 252–253.

- Klein 2016, pp. 263–264.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 135–136.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 136–137.

- Klein 2016, p. 290.

- Klein 2016, pp. 302–303.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 139–140.

- Murphy 2007, p. 28.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 141–142.

- Klein 2016, pp. 329–336.

- Klein 2016, pp. 338–339.

- Klein 2016, p. 377.

- Alexander 1995, p. 150.

- Alexander 1995, pp. 150–151.

- Klein 2016, pp. 388–394.

- Klein 2016, pp. 400.

- Klein 2016, pp. 398.

- Klein 2016, p. 426.

- Klein 2016, pp. 423–430.

- Alexander 2015, pp. 163–167.

- Klein 2016, pp. 459–460.

- Klein 2016, pp. 469–470.

- Deford 2005, p. 526.

- Alexander 2015, pp. 169–171.

- Deford, Frank (2006). The Old Ball Game. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-4247-8.

- Morris, Peter (2006). A Game of Inches: The Game on the Field. Ivan R. Dee. p. 318. ISBN 1-56663-677-9.

- McNeil, William (2006). The Evolution of Pitching in Major League Baseball. McFarland & Company. p. 53. ISBN 9780786424689. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- James, Bill (1997). The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers. Diversion Books.

- Bill Lamb (2017). "Frank McQuade". Society for American Baseball Research.

- Mcgraw, John (1995). My Thirty Years in Baseball. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8139-0.

- https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NY1/NY1193206010.shtml

- https://thejeopardyfan.com/2016/06/june-1-1932-john-mcgraws-final-mlb-game-as-new-york-giants-manager.html/2

- "John McGraw". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- "1924 New York Giants". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- "1925 New York Giants". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- "1927 New York Giants". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- "Manager McGraw's Wife Dead" (PDF). The New York Times. September 1, 1899. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- "Mrs. John J. McGraw, 81, Dies". The New York Times. November 5, 1962. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- "Mrs. John McGraw, Wife Of Former Giant Manager, Tossed Out First Ball", by Whitney Martin, for The Hartford Courant, October 6, 1951.

- "John McGraw Long Baseball Leader Dies", The Hartford Courant, February 26, 1934.

- Markoe, pp. 87

- Threston (2003). The Integration of Baseball in Philadelphia. p. 11.

Further reading

- "Mister Muggsy". Profiles. The New Yorker. 1 (6): 9–10. March 28, 1925.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John McGraw. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John McGraw |

- John McGraw at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Baseball-Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- John McGraw managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- John McGraw at SABR (Baseball BioProject)

- John McGraw at Find a Grave