Monte Irvin

Monford Merrill "Monte" Irvin (February 25, 1919 – January 11, 2016) was an American left fielder and right fielder in the Negro leagues and Major League Baseball (MLB) who played with the Newark Eagles (1938–1942, 1946–1948), New York Giants (1949–1955) and Chicago Cubs (1956). He grew up in New Jersey and was a standout football player at Lincoln University. Irvin left Lincoln to spend several seasons in Negro league baseball. His career was interrupted by military service from 1943 to 1945.

| Monte Irvin | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Irvin circa 1953 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Left fielder | |||||||||||||||||||

| Born: February 25, 1919 Haleburg, Alabama | |||||||||||||||||||

| Died: January 11, 2016 (aged 96) Houston, Texas | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| MLB debut | |||||||||||||||||||

| July 8, 1949, for the New York Giants | |||||||||||||||||||

| Last MLB appearance | |||||||||||||||||||

| September 30, 1956, for the Chicago Cubs | |||||||||||||||||||

| MLB statistics | |||||||||||||||||||

| Batting average | .293 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Home runs | 99 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Runs batted in | 443 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Teams | |||||||||||||||||||

| Negro leagues

Major League Baseball

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Member of the National | |||||||||||||||||||

| Induction | 1973 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Election Method | Negro Leagues Committee | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

When he joined the New York Giants, Irvin became one of the earliest African-American MLB players. He played in two World Series for the Giants. When future Hall of Famer Willie Mays joined the Giants in 1951, Irvin was asked to mentor him. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973. After his playing career, Irvin was a baseball scout and held an administrative role with the MLB commissioner's office.

At the time of his death, Irvin was the oldest living former Negro Leagues player, New York Giant and Chicago Cub. He lived in a retirement community in Houston prior to his death.

Early life

Irvin was born February 25, 1919,[1] in Haleburg, Alabama, the eighth of 13 children, and brother of fellow Negro leaguer Cal Irvin. As a child, he moved with his family to Orange, New Jersey. In high school, he starred in four sports and set a state record in the javelin throw. Irvin played baseball for the Orange Triangles, the local semiprofessional team, and he credited its coach with giving him an activity that helped him to stay out of trouble. He was offered a football scholarship to the University of Michigan, but he had to turn it down because he did not have enough money to move to Ann Arbor.[2]

Irvin attended Lincoln University and was a star football player. However, he had disagreements with his coach and he found that he could not remain on his athletic scholarship and pursue predentistry studies. As his frustration mounted, Irvin began to be recruited by Negro league baseball teams.[2]

Negro league and Mexican League career

Irvin played for the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League in 1938. Larry Doby, the first player to break the color barrier in the American League, was Irvin's double play partner with Newark at one time.[3] After hitting for high batting averages of .422 and .396 (1940–41), Irvin asked for a raise before the 1942 season. When that was denied, he left the Negro leagues for the Mexican League, where he won a triple crown; he had a .397 batting average and 20 home runs in 63 games.[4][5]

World War II

Following the 1942 Mexican League season, Irvin was drafted into military service. Joining the army's GS Engineers, 1313th Battalion, for the next three years, Irvin was deployed to England, France and Belgium, and he served in the Battle of the Bulge. Irvin said that while many black soldiers had been treated badly by their white counterparts, the situation improved for black soldiers as many white soldiers realized the contradiction in an oppressed group being sent to Europe to fight for the oppressed people in other countries. Irvin's military service left him with ringing in the ears, which affected his coordination.[6]

Return to baseball

After World War II, Irvin was approached by Brooklyn Dodgers executive Branch Rickey about being signed for the major leagues, but Irvin felt he was not ready to play at that level so soon after leaving the service.[7] The Newark Eagles business manager, Effa Manley, would not let Rickey sign Irvin without compensation. Rickey had already obtained Jackie Robinson without paying for his rights to his Negro league clubs. Said Irvin,

... from a purely business standpoint, Mrs. Manley felt that Branch Rickey was obligated to compensate her for my contract. That position probably delayed my entry into the major leagues ... Mrs. Manley told Rickey that he had taken Don Newcombe for no money but she wasn't going to let him take me without some compensation. Furthermore, if he tried to do it, she would sue and fight him in court ... Rickey contacted her to say he was no longer interested released me ... the Giants picked up my contract ...[8]:p.277

Irvin earned MVP honors in the 1945–46 Puerto Rican Winter League. He returned to the Newark Eagles in 1946 to lead his team to a league pennant. Irvin won his second batting championship, hitting .401, and was instrumental in beating the Kansas City Monarchs in a seven-game Negro League World Series, batting .462 with three home runs. He was a five-time Negro League All-Star (1941, 1946–48, including two games in 1946). He spent the winter of 1948–49 in Cuba.

MLB career

In 1949, the New York Giants paid $5,000 for Irvin's contract. He was one of the first black players to be signed, as Jackie Robinson had only broken the MLB color line in 1947. Assigned to Jersey City of the International League, Irvin batted .373. He debuted with the Giants on July 8, 1949, as a pinch hitter. Back with Jersey City in 1950, he was called up after hitting .510 with ten home runs in 18 games. Irvin batted .299 for the Giants that season, playing first base and the outfield.

In 1951, Irvin sparked the Giants' miraculous comeback to overtake the Dodgers in the pennant race, batting .312 with 24 homers and a league-best 121 runs batted in (RBI), en route to the World Series (he went 11–24 for .458). In the third game of the playoff between the Giants and Dodgers, Irvin popped out in the bottom of the ninth inning before Bobby Thomson hit the Shot Heard 'Round the World. That year Irvin teamed with Hank Thompson and Willie Mays to form the first all-black outfield in the majors. Later, he finished third in the NL's MVP voting.

During that season, Giants manager Leo Durocher asked Irvin to serve as a mentor for Mays, who had been called up to the team in May. Mays later said, "In my time, when I was coming up, you had to have some kind of guidance. And Monte was like my brother ... I couldn't go anywhere without him, especially on the road ... It was just a treat to be around him. I didn't understand life in New York until I met Monte. He knew everything about what was going on and he protected me dearly."[9] Irvin later replied, "I did that for two years and in the third year he started showing me around."[9]

Irvin suffered a broken ankle during a spring training game in Denver in 1952, jamming his ankle on third base while sliding. "It was a horrible thing to see," reported Mays.[10] However, Irvin returned in time to be named to his only Major League Baseball All-Star Game in 1952. He appeared in only 46 games that season, hitting .310 with four home runs and 21 RBI.[11][12] Irvin hit .329 with 21 home runs and 97 RBI in 1953, finishing 15th in the league MVP voting. The following season, he hit .262 with 19 home runs and 64 RBI,[12] with the Giants winning the pennant and facing the Cleveland Indians in the 1954 World Series. Irvin was in left field when Mays, playing center field, made "The Catch" on a deep drive off the bat of Vic Wertz in Game 1.[13] The Giants went on to win the Series in four games, with Irvin collecting two hits in nine at bats.[14]

In 1955, Irvin had been sent down to the minor leagues, where he hit 14 home runs in 75 games for the Minneapolis Millers. The Chicago Cubs signed him before the 1956 season. The team said that he would compete with Hank Sauer for a starting position in left field.[15] Irvin appeared in 111 games for the Cubs that year, hitting .271 with 15 home runs.[12]

A back injury led to Irvin's retirement as a player in 1957. He sustained the injury during spring training that year and only appeared in four minor league games for the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.[16] In his major league career, Irvin batted .293, with 99 home runs, 443 RBI, 366 runs scored, 731 hits, 97 doubles, 31 triples, and 28 stolen bases, with 351 walks for a .383 on-base percentage, and 1187 total bases for a .475 slugging average in 764 games played. Defensively, Irvin recorded a .981 fielding percentage.[12]

Later life

Monte appeared on an episode of To Tell The Truth dated May 22, 1961, in which he impersonated a judo champion.[17]

After retiring, Irvin worked as a representative for the Rheingold beer company,[18] and later as a scout for the New York Mets from 1967 to 1968. He was named an MLB public relations specialist for the commissioner's office under Bowie Kuhn in 1968. The appointment made him the first black executive in professional baseball.[19] He was elected to the Mexican Professional Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972.[20] The next year, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, primarily on the basis of his play in the Negro leagues.

In 1974, Kuhn was present in Cincinnati when Hank Aaron tied Babe Ruth's record of 714 career home runs. When the team came back to Atlanta, Kuhn sent Irvin in his place, so Kuhn was not present for Aaron's 715th home run. Even as late as 1980, Aaron was so angry at Kuhn that he did not attend an event where Kuhn was to present him with an award.[21]

Irvin stepped down from his role with the commissioner when Kuhn announced his retirement in 1984.[22] He retired to Florida, but he accepted an MLB role involving special projects and appearances.[23]

On May 16, 2006, Orange Park in the city of Orange, New Jersey was renamed Monte Irvin Park, in his honor.[24]

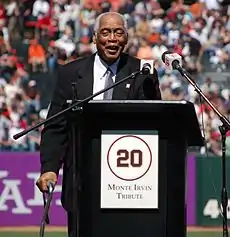

On June 26, 2010, the San Francisco Giants officially retired his number 20 uniform. He was joined by fellow Hall of Famers Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal, Gaylord Perry and Orlando Cepeda in the pre-game ceremony.[25] He later joined those same Giants Hall of Famers in throwing out the ceremonial first pitch of Game 1 of 2010 World Series.[26] In 2015, he was presented a 2014 World Series ring by Giants executives and later joined the Giants in visiting the White House.[27][28]

On January 11, 2016, Irvin died of natural causes in Houston at the age of 96.[29] At the time of his death, Irvin was the oldest living African American to have played in the major leagues, as well as the oldest living member of a World Series-winning team. Prior to his death, he lived in a retirement community in Houston.[30] He also served on the Veterans Committee of the Hall of Fame. The Giants wore a patch in his memory for the 2016 season, a black circle with an orange outline with "Monte" on top of his number 20, to be worn on the left sleeve.[31]

On October 19, 2016, a life-sized bronze statue of Irvin was dedicated in Monte Irvin Park in Orange, New Jersey.[32]

Career statistics

Negro leagues

The first official statistics for the Negro leagues were compiled as part of a statistical study sponsored by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and supervised by Larry Lester and Dick Clark, in which a research team collected statistics from thousands of box-scores of league-sanctioned games.[33] The first results from this study were the statistics for Negro league Hall of Famers elected prior to 2006, which were published in Shades of Glory by Lawrence D. Hogan. These statistics include the official Negro league statistics for Monte Irvin:

| Year | Team | G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | BA | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | Newark | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .000 | .000 |

| 1939 | Newark | 21 | 76 | 11 | 22 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 7 | .289 | .421 |

| 1940 | Newark | 35 | 131 | 26 | 46 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 36 | 2 | 12 | .351 | .550 |

| 1941 | Newark | 34 | 126 | 28 | 50 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 36 | 7 | 10 | .397 | .619 |

| 1942 | Newark | 4 | 18 | 7 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | .611 | 1.056 |

| 1945 | Newark | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | .200 | .200 |

| 1946 | Newark – c | 40 | 149 | 34 | 57 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 36 | 3 | 16 | .383 | .584 |

| 1947 | Newark | 13 | 48 | 13 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 8 | .333 | .604 |

| 1948 | Newark | 9 | 30 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 4 | .233 | .433 |

| Total | 9 seasons | 159 | 587 | 125 | 210 | 34 | 9 | 23 | 146 | 15 | 57 | .358 | .564 |

| c = pennant and Negro League World Series championship. | |||||||||||||

Source:[34]

See also

Notes

- Schudel, Matt (2016-01-12). "Monte Irvin, Hall of Fame baseball star who began in Negro leagues, dies at 96". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- Dorinson, Joseph; Warmund, Joram (1998). Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream. M. E. Sharpe. p. 33. ISBN 0765633388. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- Coyne, Kevin (April 27, 2008). "Black baseball's rich legacy". The New York Times. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- Burkett, Samantha (January 12, 2016). "Remembering Monte Irvin". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- Justice, Richard; Haft, Chris (January 12, 2016). Hall of Famer, trailblazer Irvin dies at 96. MLB.com. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Monte Irvin". www.baseballinwartime.com. May 13, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- Monte Irvin. Baseball in Wartime. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- Simons, William M. (2 October 2015). Alvin L. Hall (ed.). The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2000. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0786411207.

- Haft, Chris (April 13, 2012). "Irvin played big part in Mays' ascension". MLB.com. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- Mays, Willie (1988). Say Hey: The Autobiography of Willie Mays. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 100. ISBN 0671632922.

- Lacy, Sam (April 8, 1952). "Bums, to a man, regret injury to Monte Irvin". Baltimore Afro-American. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- "Monte Irvin Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "New York Giants 5, Cleveland Indians 2". Retrosheet. September 29, 1954. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- "1954 World Series". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- "Monte Irvin signs Cubs' contract". Baltimore Afro-American. January 3, 1956. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- "Aching back puts Irvin out for good". Milwaukee Sentinel. May 12, 1957. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- "To Tell the Truth, May 22, 1961". To Tell the Truth. May 22, 1961. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- To Tell the Truth, CBS, May 22, 1961 episode

- "Monte Irvin joins staff in New York". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. August 22, 1968. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- "Cards get Cuozzo; Stasiuk fired". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. April 27, 1972. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- "Angered Aaron snubs Kuhn at award ceremony". Lakeland Ledger. January 29, 1980. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- "Irvin to retire with Kuhn". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. January 18, 1984. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- Bock, Hal (March 1, 1984). "Monte Irvin a class guy". Lewiston Journal. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- "Monte Irvin | In Honor". www.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2017-08-14.

- "Giants to retire uniform #20 worn by Monte Irvin". San Francisco Giants.

- "Giants greats, sans Mays, take part in pregame". Major League Baseball.

- Shea, John (May 13, 2015). "Monte Irvin, 96, gets his Giants ring from Larry Baer, Bobby Evans". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Baggarly, Andrew (June 4, 2015). "Giants visit White House for World Series celebration". San Jose Mercury News.

- "Hall of Famer Monte Irvin dies at 96". USA Today. January 12, 2016.

- Barron, David (May 28, 2014). "Hall of Famer Irvin laments diminishing number of African-Americans in baseball". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- @SFGiants (March 29, 2016). "The #SFGiants will wear patches on their sleeve in honor of @BaseballHall of Famer Monte Irvin and Jim Davenport" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Essex County Dedicates Monte Irvin Statue in (Monte Irvin) Orange Park". TAPinto. Retrieved 2017-08-14.

- Hogan, p. 381.

- Hogan, pp. 390–391.

- Treto Cisneros, p. 27, 31, 293.

References

- Clark, Dick; Lester, Larry (1994), The Negro Leagues Book, Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research

- Hogan, Lawrence D. (2006), Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball, Washington, D.C.: National Geographic, ISBN 0-7922-5306-X

- Holway, John B. (2001), The Complete Book of Baseball's Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History, Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House Publishers, ISBN 0-8038-2007-0

- Riley, James A. (1994), The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf, ISBN 0-7867-0959-6

- Treto Cisneros, Pedro (2002), The Mexican League: Comprehensive Player Statistics, 1937–2001, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, ISBN 0-7864-1378-6

Further reading

Articles

- United Press. "Irvin's Injury Dims Giant Hopes; Star Breaks Ankle, May Be Sidelined for Rest of Season". The Pittsburgh Press. April 3, 1952.

- Fraley, Oscar. "Ankle Injured, Monte Irvin Has Plentitude Of Troubles But Still Hopes For Batting Crown". Madeira Daily News-Tribune. August 14, 1953.

- "'That Boy's So Full of Play'; Two close friends of Willie Mays talk about frisky personality of newly legendary Giant". Life. September 13, 1954. pp. 133–134, 137-138, 141.

- Trimble, Joe. Irvin Makes Long Road to Hall of Fame". Daily News. February 8, 1973.

- Richman, Milton (UPI). "Monte Couldn't Fool His Wife". The Desert Sun. February 8, 1973.

Books

- Irvin, Monte; Riley, James A. (1996). Monte Irvin: Nice Guys Finish First. ISBN 9780786702541

- Irvin, Monte; Pepe, Phil (2007). Few and Chosen: Defining Negro League Greatness. Chicago, IL: Triumph Books. ISBN 9781572438552.

- Anton, Todd; Nowlin, Bill, ed. (2008). When Baseball Went to War. Chicago, IL: Triumph Books. pp. 117-180. ISBN 9781600781261.

External links

- Monte Irvin at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Negro league baseball statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference (Negro leagues)

- St. Petersburg Times – Profile

- cmgww.com – Official website

- legacymemorybank.org – Monte Irvin interview on Martin Luther King, Jr.