Julius Caesar's invasions of Britain

In the course of his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar invaded Britain twice: in 55 and 54 BC.[4] On the first occasion Caesar took with him only two legions, and achieved little beyond a landing on the coast of Kent. The second invasion consisted of 628 ships, five legions and 2,000 cavalry. The force was so imposing that the Britons did not dare contest Caesar's landing in Kent, waiting instead until he began to move inland.[3] Caesar eventually penetrated into Middlesex and crossed the Thames, forcing the British warlord Cassivellaunus to surrender as a tributary to Rome and setting up Mandubracius of the Trinovantes as client king.

| Caesar's invasions of Britain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Caesar's Gallic Wars | |||||||||

Roman invasion of Britain in Kent 55–54 BC | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Roman Republic | Celtic Britons | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Julius Caesar | Cassivellaunus | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

55 BC 7,000–10,000 legionaries plus cavalry and auxiliaries 100 transport ships[1] 54 BC 17,500–25,000 legionaries 2,000 cavalry 600 transports[2] 28 warships[3] | Unknown | ||||||||

Britain before Caesar

.jpg.webp)

Britain had long been known to the classical world as a source of tin. The coastline had been explored by the Greek geographer Pytheas in the 4th century BC, and may have been explored even earlier, in the 5th century, by the Carthaginian sailor Himilco. But to many Romans, the island, lying as it did beyond the Ocean at what was to them the edge of the known world, was a land of great mystery. Some Roman writers even insisted that it did not exist,[6] and dismissed reports of Pytheas's voyage as a hoax.[7]

Britain during the reign of Julius Caesar had an Iron Age culture, with an estimated population of between one and four million. Archaeological research shows that its economy was broadly divided into lowland and highland zones. In the lowland southeast, large areas of fertile soil made possible extensive arable farming, and communication developed along trackways, such as the Icknield Way, the Pilgrims' Way and the Jurassic Way, and navigable rivers such as the Thames. In the highlands, north of the line between Gloucester and Lincoln, arable land was available only in isolated pockets, so pastoralism, supported by garden cultivation, was more common than settled farming, and communication was more difficult. Settlements were generally built on high ground and fortified, but in the southeast, oppida had begun to be established on lower ground, often at river crossings, suggesting that trade was becoming more important. Commercial contact between Britain and the continent had increased since the Roman conquest of Transalpine Gaul in 124 BC, and Italian wine was being imported via the Armorican peninsula, much of it arriving at Hengistbury Head in Dorset.[8]

Caesar's written account of Britain says that the Belgae of northeastern Gaul had previously conducted raids on Britain, establishing settlements in some of its coastal areas, and that within living memory Diviciacus, king of the Suessiones, had held power in Britain as well as in Gaul.[9] British coinage from this period shows a complicated pattern of intrusion. The earliest Gallo-Belgic coins that have been found in Britain date to before 100 BC, perhaps as early as 150 BC, were struck in Gaul, and have been found mainly in Kent. Later coins of a similar type were struck in Britain and are found all along the south coast as far west as Dorset. It appears that Belgic power was concentrated on the southeastern coast, although their influence spread further west and inland, perhaps through chieftains establishing political control over the native population.[10]

First invasion (55 BC)

Planning and reconnaissance

Caesar claimed that, in the course of his conquest of Gaul, the Britons had supported the campaigns of the mainland Gauls against him, with fugitives from among the Gallic Belgae fleeing to Belgic settlements in Britain,[11] and the Veneti of Armorica, who controlled seaborne trade to the island, calling in aid from their British allies to fight for them against Caesar in 56 BC.[12] Strabo says that the Venetic rebellion in 56 BC had been intended to prevent Caesar from travelling to Britain and disrupting their commercial activity,[13] suggesting that the possibility of a British expedition had already been considered by then.

In late summer, 55 BC, even though it was late in the campaigning season, Caesar decided to make an expedition to Britain. He summoned merchants who traded with the island, but they were unable or unwilling to give him any useful information about the inhabitants and their military tactics, or about harbours he could use, presumably not wanting to lose their monopoly on cross-channel trade. He sent a tribune, Gaius Volusenus, to scout the coast in a single warship. He probably examined the Kent coast between Hythe and Sandwich, but was unable to land, since he "did not dare leave his ship and entrust himself to the barbarians",[14] and after five days returned to give Caesar what intelligence he had managed to gather.

By then, ambassadors from some of the British states, warned by merchants of the impending invasion, had arrived promising their submission. Caesar sent them back, along with his ally Commius, king of the Belgae Atrebates, to use their influence to win over as many other states as possible.

He gathered a fleet consisting of eighty transport ships, sufficient to carry two legions (Legio VII and Legio X), and an unknown number of warships under a quaestor, at an unnamed port in the territory of the Morini, almost certainly Portus Itius (Boulogne). Another eighteen transports of cavalry were to sail from a different port, probably Ambleteuse.[15] These ships may have been triremes or biremes, or may have been adapted from Venetic designs Caesar had seen previously, or may even have been requisitioned from the Veneti and other coastal tribes. Clearly in a hurry, Caesar himself left a garrison at the port and set out "at the third watch" – well after midnight – on 23 August[16][17] with the legions, leaving the cavalry to march to their ships, embark, and join him as soon as possible. In light of later events, this was either a tactical mistake or (along with the fact that the legions came over without baggage or heavy siege gear)[18] confirms the invasion was not intended for complete conquest.

Landing

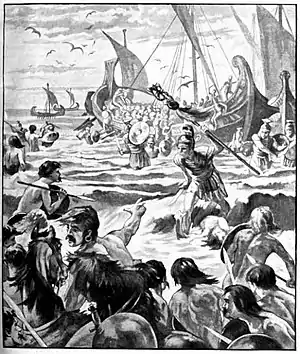

Caesar initially tried to land at Dubris (Dover), whose natural harbour had presumably been identified by Volusenus as a suitable landing place. However, when he came in sight of shore, the massed forces of the Britons gathered on the overlooking hills and cliffs dissuaded him from landing there, since the cliffs were so close to the shore that javelins could be thrown down from them onto anyone landing there.[19] After waiting there at anchor "until the ninth hour" (about 3pm) waiting for his supply ships from the second port to come up and meanwhile convening a council of war, he ordered his subordinates to act on their own initiative and then sailed the fleet about 7 miles (11 kilometres) North East along the coast to an open beach. The first level beach area after Dover is at Walmer where a memorial is placed. Recent archaeology by the University of Leicester indicates that the possible landing beach was in Pegwell Bay on the Isle of Thanet, Kent, where artefacts and massive earthworks dating from this period have been exposed, although this area would not have been the first easy landing site seen after Dover. If Caesar had as large a fleet with him as has been suggested, then it is possible that the beaching of ships would have been spread out over a number of miles stretching from Walmer towards Pegwell Bay.[20]

Having been tracked all the way along the coast by the British cavalry and chariots, the landing was opposed. To make matters worse, the loaded Roman ships were too low in the water to go close inshore and the troops had to disembark in deep water, all the while attacked by the enemy from the shallows. The troops were reluctant, but according to Caesar's account were led by the aquilifer (standard-bearer, whose name is not provided by Caesar) of the 10th legion who jumped in first as an example, shouting:

- "Leap, fellow soldiers, unless you wish to betray your eagle to the enemy. I, for my part, will perform my duty to the republic and to my general."[21]

The British were eventually driven back with catapultae and slings fired from the warships into the exposed flank of their formation and the Romans managed to land and drive them off. The cavalry, delayed by adverse winds, still had not arrived, so the Britons could not be pursued and finished off, and Caesar could not enjoy what he calls, in his usual self-promoting style, his "accustomed success".[22]

Beach-head

The Romans established a camp of which archaeological traces have been found, received ambassadors and had Commius, who had been arrested as soon as he had arrived in Britain, returned to them. Caesar claims he was negotiating from a position of strength and that the British leaders, blaming their attacks on him on the common people, were in only four days awed into giving hostages, some immediately, some as soon as they could be brought from inland, and disbanding their army. However, after his cavalry had come within sight of the beachhead but then been scattered and turned back to Gaul by storms, and with food running short, Caesar, a native of the Mediterranean, was taken by surprise by high British tides and a storm. His beached warships filled with water, and his transports, riding at anchor, were driven against each other. Some ships were wrecked, and many others were rendered unseaworthy by the loss of rigging or other vital equipment, threatening the return journey.

Realising this and hoping to keep Caesar in Britain over the winter and thus starve him into submission, the Britons renewed the attack, ambushing one of the legions as it foraged near the Roman camp. The foraging party was relieved by the remainder of the Roman force and the Britons were again driven off, only to regroup after several days of storms with a larger force to attack the Roman camp. This attack was driven off fully, in a bloody rout, with improvised cavalry that Commius had gathered from pro-Roman Britons and a Roman scorched earth policy.

Conclusion

The British once again sent ambassadors and Caesar, although he doubled the number of hostages, realised he could not hold out any longer and dared not risk a stormy winter crossing. Caesar had set out late in the campaigning season and the winter was approaching, and so he allowed them to be delivered to him in Gaul, to which he returned with as many of the ships as could be repaired with flotsam from the wrecked ships. Even then, only two tribes felt sufficiently threatened by Caesar to actually send the hostages, and two of his transports were separated from the main body and made landfall elsewhere.

Success and motivation

If the invasion was intended as a full-scale campaign, invasion or occupation, it had failed, and if it is seen as a reconnaissance-in-force or a show of strength to deter further British aid to the Gauls, it had fallen short. Nonetheless, going to Britain beyond the "known world" carried such kudos for a Roman that the Senate decreed a supplicatio (thanksgiving) of twenty days when they received Caesar's report. It is also suggested that this invasion established alliances with British kings in the area which smoothed the later invasion of AD 43.[23]

Caesar's pretext for the invasion was that "in almost all the wars with the Gauls succours had been furnished to our enemy from that country". This is plausible, although it may also have been a cover for investigating Britain's mineral resources and economic potential: afterwards, Cicero refers to the disappointing discovery that there was no gold or silver in the island;[24] and Suetonius reports that Caesar was said to have gone to Britain in search of pearls.[25]

Second invasion (54 BC)

Preparation

A second invasion was planned in the winter of 55–54 for the summer of 54 BC. Cicero wrote letters to his friend Gaius Trebatius Testa and his brother Quintus, both of whom were serving in Caesar's army, expressing his excitement at the prospect. He urged Trebatius to capture him a war chariot, and asked Quintus to write him a description of the island. Trebatius, as it turned out, did not go to Britain, but Quintus did, and wrote him several letters from there – as did Caesar himself.[26]

Determined not to make the same mistakes as the previous year, Caesar gathered a larger force than on his previous expedition with five legions as opposed to two, plus two thousand cavalry, carried in ships which he designed, with experience of Venetic shipbuilding technology so as to be more suitable for a beach landing than those used in 55 BC, being broader and lower for easier beaching. This time he named Portus Itius as the departure point.[27]

Crossing and landing

Titus Labienus was left at Portus Itius to oversee regular food transports from there to the British beachhead. The military ships were joined by a flotilla of trading ships captained by Romans and provincials from across the empire, and local Gauls, hoping to cash in on the trading opportunities. It seems more likely that the figure Caesar quotes for the fleet (800 ships) include these traders and the troop-transports, rather than the troop-transports alone.

Caesar landed at the place he had identified as the best landing-place the previous year. The Britons did not oppose the landing, apparently, as Caesar states, intimidated by the size of the fleet, but this may have been a strategic ploy to give them time to gather their forces.

Kent campaign

Upon landing, Caesar left Quintus Atrius in charge of the beach-head and made an immediate night march 12 mi (19 km) inland, where he encountered the British forces at a river crossing, probably somewhere on the River Stour. The Britons attacked but were repulsed, and attempted to regroup at a fortified place in the forests, possibly the hillfort at Bigbury Wood, Kent,[28] but were again defeated and scattered. As it was late in the day and Caesar was unsure of the territory, he called off the pursuit and made camp.

However, the next morning, as he prepared to advance further, Caesar received word from Atrius that, once again, his ships at anchor had been dashed against each other in a storm and suffered considerable damage. About forty, he says, were lost. The Romans were unused to Atlantic and Channel tides and storms, but nevertheless, considering the damage he had sustained the previous year, this was poor planning on Caesar's part. However, Caesar may have exaggerated the number of ships wrecked to magnify his own achievement in rescuing the situation.[29] He returned to the coast, recalling the legions that had gone ahead, and immediately set about repairing his fleet. His men worked day and night for approximately ten days, beaching and repairing the ships, and building a fortified camp around them. Word was sent to Labienus to send more ships.

Caesar was on the coast on 1 September, from where he wrote a letter to Cicero. News must have reached Caesar at this point of the death of his daughter Julia, as Cicero refrained from replying "on account of his mourning".[30]

March inland

Caesar then returned to the Stour crossing and found the Britons had massed their forces there. Cassivellaunus, a warlord from north of the Thames, had previously been at war with most of the British tribes. He had recently overthrown the king of the powerful Trinovantes and forced his son, Mandubracius, into exile. But now, facing invasion, the Britons had appointed Cassivellaunus to lead their combined forces. After several indecisive skirmishes, during which a Roman tribune, Quintus Laberius Durus, was killed, the Britons attacked a foraging party of three legions under Gaius Trebonius, but were repulsed and routed by the pursuing Roman cavalry.

Cassivellaunus realised he could not defeat Caesar in a pitched battle. Disbanding the majority of his force and relying on the mobility of his 4,000 chariots and superior knowledge of the terrain, he used guerrilla tactics to slow the Roman advance. By the time Caesar reached the Thames, the one fordable place available to him had been fortified with sharpened stakes, both on the shore and under the water, and the far bank was defended. Second Century sources state that Caesar used a large war elephant, which was equipped with armour and carried archers and slingers in its tower, to put the defenders to flight. When this unknown creature entered the river, the Britons and their horses fled and the Roman army crossed over and entered Cassivellaunus' territory.[31]

The Trinovantes, whom Caesar describes as the most powerful tribe in the region, and who had recently suffered at Cassivellaunus' hands, sent ambassadors, promising him aid and provisions. Mandubracius, who had accompanied Caesar, was restored as their king, and the Trinovantes provided grain and hostages. Five further tribes, the Cenimagni, Segontiaci, Ancalites, Bibroci and Cassi, surrendered to Caesar, and revealed to him the location of Cassivellaunus' stronghold, possibly the hill fort at Wheathampstead,[32] which he proceeded to put under siege.

Cassivellaunus sent word to his allies in Kent, Cingetorix, Carvilius, Taximagulus and Segovax, described as the "four kings of Cantium",[33] to stage a diversionary attack on the Roman beach-head to draw Caesar off, but this attack failed, and Cassivellaunus sent ambassadors to negotiate a surrender. Caesar was eager to return to Gaul for the winter due to growing unrest there, and an agreement was mediated by Commius. Cassivellaunus gave hostages, agreed an annual tribute, and undertook not to make war against Mandubracius or the Trinovantes. Caesar wrote to Cicero on 26 September, confirming the result of the campaign, with hostages but no booty taken, and that his army was about to return to Gaul.[34] He then left, leaving not a single Roman soldier in Britain to enforce his settlement. Whether the tribute was ever paid is unknown.

Aftermath

Commius later switched sides, fighting in Vercingetorix's rebellion. After a number of unsuccessful engagements with Caesar's forces, he cut his losses and fled to Britain. Sextus Julius Frontinus, in his Strategemata, describes how Commius and his followers, with Caesar in pursuit, boarded their ships. Although the tide was out and the ships still beached, Commius ordered the sails raised. Caesar, still some distance away, assumed the ships were afloat and called off the pursuit.[35] John Creighton (archaeologist) believes that this anecdote was a legend,[36] and that Commius was sent to Britain as a friendly king as part of his truce with Mark Antony.[37] Commius established a dynasty in the Hampshire area, known from coins of Gallo-Belgic type. Verica, the king whose exile prompted Claudius's conquest of AD 43, styled himself a son of Commius.

Discoveries about Britain

As well as noting elements of British warfare, particularly the use of chariots, which were unfamiliar to his Roman audience, Caesar also aimed to impress them by making further geographical, meteorological and ethnographic investigations of Britain. He probably gained these by enquiry and hearsay rather than direct experience, as he did not penetrate that far into the interior, and most historians would be wary of applying them beyond the tribes with whom he came into direct contact.

Geographical and meteorological

Caesar's first-hand discoveries were limited to east Kent and the Thames Valley, but he was able to provide a description of the island's geography and meteorology. Though his measurements are not wholly accurate, and may owe something to Pytheas, his general conclusions even now seem valid:

- The climate is more temperate than in Gaul, the colds being less severe.[38]

- The island is triangular in its form, and one of its sides is opposite to Gaul. One angle of this side, which is in Kent, whither almost all ships from Gaul are directed, [looks] to the east; the lower looks to the south. This side extends about 500 miles. Another side lies toward Hispania and the west, on which part is Ireland, less, as is reckoned, than Britain, by one half: but the passage from it into Britain is of equal distance with that from Gaul. In the middle of this voyage, is an island, which is called Mona: many smaller islands besides are supposed to lie there, of which islands some have written that at the time of the winter solstice it is night there for thirty consecutive days. We, in our inquiries about that matter, ascertained nothing, except that, by accurate measurements with water, we perceived the nights to be shorter there than on the continent. The length of this side, as their account states, is 700 miles. The third side is toward the north, to which portion of the island no land is opposite; but an angle of that side looks principally toward Germany. This side is considered to be 800 miles in length. Thus the whole island is about 2,000 miles in circumference.[39]

No information about harbours or other landing-places was available to the Romans before Caesar's expeditions, so Caesar was able to make discoveries of benefit to Roman military and trading interests. Volusenus's reconnaissance voyage before the first expedition apparently identified the natural harbour at Dubris (Dover), although Caesar was prevented from landing there and forced to land on an open beach, as he did again the following year, perhaps because Dover was too small for his much larger forces. The great natural harbours further up the coast at Rutupiae (Richborough), which were used by Claudius for his invasion 100 years later, were not used on either occasion. Caesar may have been unaware of them, may have chosen not to use them, or they may not have existed in a form suitable for sheltering and landing such a large force at that time. Present knowledge of the period geomorphology of the Wantsum Channel that created that haven is limited.

By Claudius's time Roman knowledge of the island would have been considerably increased by a century of trade and diplomacy, and four abortive invasion attempts. However, it is likely that the intelligence gathered in 55 and 54 BC would have been retained in the now-lost state records in Rome, and been used by Claudius in the planning of his landings.

Ethnography

The Britons are defined as typical barbarians, with polygamy and other exotic social habits, similar in many ways to the Gauls,[40] yet as brave adversaries whose crushing can bring glory to a Roman:

- The interior portion of Britain is inhabited by those of whom they say that it is handed down by tradition that they were born in the island itself: the maritime portion by those who had passed over from the country of the Belgae for the purpose of plunder and making war; almost all of whom are called by the names of those states from which being sprung they went thither, and having waged war, continued there and began to cultivate the lands. The number of the people is countless, and their buildings exceedingly numerous, for the most part very like those of the Gauls... They do not regard it lawful to eat the hare, and the cock, and the goose; they, however, breed them for amusement and pleasure.[38]

- The most civilised of all these nations are they who inhabit Kent, which is entirely a maritime district, nor do they differ much from the Gallic customs. Most of the inland inhabitants do not sow corn, but live on milk and flesh, and are clad with skins. All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which occasions a bluish colour, and thereby have a more terrible appearance in fight. They wear their hair long, and have every part of their body shaved except their head and upper lip. Ten and even twelve have wives common to them, and particularly brothers among brothers, and parents among their children; but if there be any issue by these wives, they are reputed to be the children of those by whom respectively each was first espoused when a virgin.[41]

Military

In addition to infantry and cavalry, the Britons employed chariots, a novelty to the Romans, in warfare. Caesar describes their use as follows:

- Their mode of fighting with their chariots is this: firstly, they drive about in all directions and throw their weapons and generally break the ranks of the enemy with the very dread of their horses and the noise of their wheels; and when they have worked themselves in between the troops of horse, leap from their chariots and engage on foot. The charioteers in the meantime withdraw some little distance from the battle, and so place themselves with the chariots that, if their masters are overpowered by the number of the enemy, they may have a ready retreat to their own troops. Thus they display in battle the speed of horse, [together with] the firmness of infantry; and by daily practice and exercise attain to such expertness that they are accustomed, even on a declining and steep place, to check their horses at full speed, and manage and turn them in an instant and run along the pole, and stand on the yoke, and thence betake themselves with the greatest celerity to their chariots again.[42]

Technology

During the civil war, Caesar made use of a kind of boat he had seen used in Britain, similar to the Irish currach or Welsh coracle. He describes them thus:

- [T]he keels and ribs were made of light timber, then, the rest of the hull of the ships was wrought with wicker work, and covered over with hides.[43]

Religion

Economic resources

Caesar not only investigates this for the sake of it, but also to justify Britain as a rich source of tribute and trade:

- [T]he number of cattle is great. They use either brass or iron rings, determined at a certain weight, as their money. Tin is produced in the midland regions; in the maritime, iron; but the quantity of it is small: they employ brass, which is imported. There, as in Gaul, is timber of every description, except beech and fir.[38]

This reference to the 'midland' is inaccurate as tin production and trade occurred in the southwest of England, in Cornwall and Devon, and was what drew Pytheas and other traders. However, Caesar only penetrated to Essex and so, receiving reports of the trade whilst there, it would have been easy to perceive the trade as coming from the interior.

Outcome

Caesar made no conquests in Britain, but his enthroning of Mandubracius marked the beginnings of a system of client kingdoms there, thus bringing the island into Rome's sphere of political influence. Diplomatic and trading links developed further over the next century, opening up the possibility of permanent conquest, which was finally begun by Claudius in AD 43. In the words of Tacitus:

- It was, in fact, the deified Julius who first of all Romans entered Britain with an army: he overawed the natives by a successful battle and made himself master of the coast; but it may be said that he revealed, rather than bequeathed, Britain to Rome.[45]

Lucan’s Pharsalia (II,572) makes the jibe that Caesar had:

- ...run away in terror from the Britons whom he had come to attack!

In later literature and culture

Classical works

- Valerius Maximus's Memorable Words and Deeds (1st century AD) praises the bravery of Marcus Caesius Scaeva, a centurion under Caesar, who, having been deserted by his comrades, held his position alone against a horde of Britons on a small island, before finally swimming to safety.[46]

- Polyaenus's 2nd-century Strategemata relates that, when Cassivellaunus was defending a river crossing against him, Caesar gained passage by the use of an armoured elephant, which terrified the Britons into fleeing.[31] This may be a confusion with Claudius's use of elephants during his conquest of Britain in AD 43.[47]

- Orosius's 5th-century History Against the Pagans contains a brief account of Caesar's invasions,[48] which makes an influential mistake: Quintus Laberius Durus, the tribune who died in Britain, is misnamed "Labienus", an error which is followed by all medieval British accounts.

Medieval works

- Bede's History of the English Church and People[49] includes an account of Caesar's invasions. This account is taken almost word for word from Orosius, which suggests Bede read a copy of this work from the library at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Priory which Benedict Biscop had brought from Rome itself.

- The 9th-century Historia Britonum attributed to Nennius gives a garbled account,[50] in which Caesar invades three times, landing at the Thames Estuary rather than on a beach in Kent. His chief opponent is Dolobellus, proconsul of the British king Belinus, son of Minocannus. Caesar finally defeats the Britons at a place called Trinovantum.

- Henry of Huntingdon's 12th-century Historia Anglorum gives an account based on Bede and the Historia Britonum, and gives Caesar an inspirational speech to his troops.[51]

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his History of the Kings of Britain,[52] has Caesar invading Britain, and has Cassibelanus (i.e. Cassivellaunus) as Caesar's primary opponent, but otherwise differs from the historical record. As in the Historia Britonum, Caesar invades three times, not twice, landing at the Thames Estuary. His story is also largely based on Bede and the Historia Britonum, but is greatly expanded. Historical elements are modified – the stakes placed in the Thames by the Britons become anti-ship rather than anti-infantry and anti-cavalry devices[53] – and other elements, such as Cassibelanus's brother Nennius engaging in hand-to-hand combat with Caesar and stealing his sword, called Crocea Mors, are not known from any earlier source. Adaptations such as Wace's Roman de Brut, Layamon's Brut and the Welsh Bruts largely follow Geoffrey's story.

- The medieval Welsh Triads also refer to Caesar's invasions. Some of these references appear directly related to Geoffrey's account, but others allude to independent traditions: Caswallawn (Cassivellaunus) is said to have gone to Rome in search of his lover, Fflur, to have allowed Caesar to land in Britain in return for a horse called Meinlas, and pursued Caesar in a great fleet after he returned to Gaul.[54] The 18th-century collection of Triads compiled by Iolo Morganwg contains expanded versions of these traditions.[55]

- The 13th-century French work Li Fet des Romains contains an account of Caesar's invasions based partly on Caesar and partly on Geoffrey. It adds an explanation of how Caesar's soldiers overcame the stakes in the Thames – they tied wooden splints filled with sulphur around them, and burned them using Greek fire. It also identifies the standard-bearer of the 10th legion as Valerius Maximus's Scaeva.[56]

- In the 14th-century French romance Perceforest Caesar, a precocious 21-year-old warrior, invades Britain because one of his knights, Luces, is in love with the wife of the king of England. Afterwards, a Briton called Orsus Bouchesuave takes a lance which Caesar used to kill his uncle, makes twelve iron styluses from the head, and, alongside Brutus, Cassius and other senators, uses them to stab Caesar to death.[56]

20th century popular culture

- E. Nesbit's 1906 children's novel The Story of the Amulet depicts Caesar on the shores of Gaul, contemplating an invasion.

- In Robert Graves's 1934 and 1935 novels I, Claudius and Claudius the God, Claudius refers to Caesar's invasions when discussing his own invasion. In the 1976 TV adaptation of the two books they are mentioned in a scene during Augustus's reign where young members of the imperial family are playing a board game (not unlike Risk) in which areas of the empire must be conquered and arguing about how many legions it theoretically needs to capture and hold Britain, and again in the speech in which Claudius announces his own invasion ("100 years since the divine Julius left it, Britain is once again a province of Rome").

- The 1957 Goon Show episode The Histories of Pliny the Elder, a pastiche of epic films, involves Caesar invading Britain, defeating the Britons who think the battle is a football match and so only send 10 men against the Romans, and occupying Britain for 10 years or more.

- The 1964 film Carry On Cleo features Caesar and Mark Antony (not present during either invasion) invading Britain and enslaving cavemen there.

- In Goscinny and Uderzo's 1965 comic Asterix in Britain, Caesar has successfully conquered Britain because the Britons stop fighting every afternoon for a cup of hot water with milk, tea not yet having been brought to Europe.

See also

References

Notes

Citations

- Snyder 2008, p. 22.

- Bunson 2014, p. 70.

- Haywood 2014, p. 64.

- Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 4.20–35, 5.1, 8–23; Dio Cassius, Roman History 39.50–53, 40.1–3; Florus, Epitome of Roman History 1.45

- Dheere c. 1550.

- Plutarch, Life of Caesar 23.2

- e.g. Strabo, Geography 2:4.1, written soon after Caesar; Polybius, Histories 34.5 – although his demolition of Pytheas may have been to glorify his own more modest Atlantic expedition – see Barry Cunliffe, The Extraordinary Voyage of Pytheas the Greek

- Frere 1987, pp. 6-9.

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 2.4, 5.12

- Frere 1987, pp. 9-15.

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 2.4, 5.12 – although whether Iron Age settlements of this period were "Belgic" in our sense of the word is debated.

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 3.8–9

- Strabo's Geography — Book IV Chapter 4, Loeb Classical Library, via LacusCurtius

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 4.22

- Frere 1987, p. 19.

- "Doubt over date for Brit invasion". BBC News. 1 July 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- Blaschke 2008.

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 4.30

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 4.23

- "In the Footsteps of Caesar: The archaeology of the first Roman invasions of Britain". University of Leicester. n.d. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 4.25

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 4.26

- "First evidence for Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain discovered — University of Leicester". www2.le.ac.uk. 29 November 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Cicero, Letters to friends 7.7; Letters to Atticus 4.17

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars: Julius 47. Caesar did later dedicate a thorax decorated with British pearls to Venus Genetrix in the temple to her that he later built (Pliny, Natural History : IX.116) and oysters were later exported from Britain to Rome (Pliny, Natural History) IX.169 and Juvenal, Satire IV.141

- Letters to friends 7.6, 7.7, 7.8, 7.10, 7.17; Letters to his brother Quintus 2.13, 2.15, 3.1; Letters to Atticus 4.15, 4.17, 4.18

- "Invasion of Britain". unrv.com. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- Frere 1987, p. 22.

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 5.23

- Cicero, Letters to his brother Quintus 3.1

- Polyaenus, Strategemata 8:23.5

- Frere 1987, p. 25.

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 5.22

- Letters to Atticus 4.18

- Frontinus, Strategemata 2:13.11

- Creighton 2000, p. 63.

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 8.48

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 5.12

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 5.13

- cf. his similar ethnographic treatment of them in Commentarii de Bello Gallico 6.11.20

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 5.14

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 4.33

- Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili 1.54

- Commentarii de Bello Gallico 6.13

- Tacitus, Agricola 13

- Valerius Maximus, Actorum et Dictorum Memorabilium Libri Novem 3:2.23

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 60.21

- Orosius, Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII 6.9

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History 1.2

- Historia Britonum 19–20

- Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum 1.12–14

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae 4.1–10

- Compare De Bello Gallico 5.18 with Historia Regum Britanniae 4.6

- Peniarth Triads 32; Hergest Triads 5, 21, 50, 58

- Iolo Morganwg, Triads of Britain 8, 14, 17, 21, 24, 51, 100, 102, 124

- Nearing 1949, pp. 889-929.

First invasion

- Caesar, De Bello Gallico, 4.20 – .37

- Dio Cassius, 39.50 – .53

Second invasion

General

- Tacitus, Agricola 13

- Suetonius, Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Julius 25, 47

- Plutarch, Caesar 16.5, 23.2;

- Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.46–47

- Appian,

- Eutropius, Abridgement of Roman History 6.17

- Livy

- Orosius, Histories Against the Pagans 6.9.

- Dheere, Luc (c. 1550). Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre avec leurs habits et ornemens divers, tant anciens que modernes, diligemment depeints au naturel – via Ghent University Library.

Modern

- Blaschke, Jayme (23 June 2008). "Tide and time: Re-dating Caesar's invasion of Britain". Texas State University. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- Bunson, Matthew (2014). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1027-1.

- Creighton, John (2000). Coins and Power in Late Iron Age Britain. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-43172-9.

- Frere, Sheppard Sunderland (1987). Britannia: A History of Roman Britain (3rd ed.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7102-1215-3.

- Haywood, John (2014). The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87017-3.

- Nearing, Homer (1949). "The Legend of Julius Caesar's British Conquest". PLMA. Modern Language Association. 64 (4): 889–929. JSTOR 459639.

- Peter Salway,11 Roman Britain (Oxford History of England), chapter 2 (pages 20–39)

- John Peddie, 1987, Conquest: The Roman Conquest of Britain, chapter 1 (pages 1–22)

- T. Rice Holmes, 1907. Ancient Britain and the Invasions of Julius Caesar. Oxford. Clarendon Press.

- R. C. Carrington, 1938, "Caesar's Invasions of Britain" by (reviewed in Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 29, Part 2 (1939), pp. 276–277)

- Peter Berresford Ellis, Caesar's Invasion of Britain, 1978, ISBN 978-0-85613-018-2

- Snyder, Christopher A. (2008). The Britons. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-75821-2.

- W. Welch, C. G. Duffield (Editor), Caesar: Invasion of Britain, 1981, ISBN 978-0-86516-008-8