Kemp's ridley sea turtle

Kemp's ridley sea turtle[3] (Lepidochelys kempii), also called the Atlantic ridley sea turtle, is the rarest species of sea turtle and is the world's most endangered species of sea turtles. It is one of two living species in the genus Lepidochelys (the other one being L. olivacea, the olive ridley sea turtle).

| Kemp's ridley sea turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lepidochelys kempii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Chelonioidea |

| Family: | Cheloniidae |

| Genus: | Lepidochelys |

| Species: | L. kempii |

| Binomial name | |

| Lepidochelys kempii (Garman, 1880) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

This species of turtle is called Kemp's ridley because Richard Moore Kemp (1825-1908) of Key West was the first to send a specimen to Samuel Garman at Harvard.[4] However, the etymology of the name "ridley" itself is unknown. Prior to the term being popularly used (for both species in the genus), L. kempii at least was known as the "bastard turtle".[5]

At least one source also refers to Kemp's ridley as a "heartbreak turtle". In her book The Great Ridley Rescue, Pamela Philips claimed the name was coined by fishermen who witnessed the turtles dying after being "turned turtle" (on their backs). The fishermen said the turtles "died of a broken heart".[6][7]

Description

Kemp's ridley is the smallest of all sea turtle species, reaching maturity at 58–70 cm (23–28 in) carapace length and weighing only 36–45 kg (79–99 lb).[8] Typical of sea turtles, it has a dorsoventrally depressed body with specially adapted flipper-like front limbs and a beak. Kemp's ridley turtle is the smallest of the sea turtles, with adults reaching a maximum of 75 cm (30 in) in carapace length and weighing a maximum of 50 kg (110 lb).[8] The adult has an oval carapace that is almost as wide as it is long and is usually olive-gray in color. The carapace has five pairs of costal scutes. In each bridge adjoining the plastron to the carapace are four inframarginal scutes, each of which is perforated by a pore. The head has two pairs of prefrontal scales.

These turtles change color as they mature. As hatchlings, they are almost entirely a dark purple on both sides, but mature adults have a yellow-green or white plastron and a grey-green carapace .[9]

Kemp's ridley has a triangular-shaped head with a somewhat hooked beak with large crushing surfaces. The skull is similar to that of the olive ridley.[10] Unlike other sea turtles, the surface on the squamosal bone where the jaw opening muscles originate, faces to the side rather than to the back.[11]

They are the only sea turtle that nests during the day.[12]

Distribution

The distribution of Lepidochelys kempii is somewhat usual compared to most reptiles, varying significantly among adults and juveniles as well as males and females. Adults primarily live in the Gulf of Mexico where they forage in the relatively shallow waters of the continental shelf (up to 409 meters deep but typically <50 meters or less),[16] with females ranging from the southern coast of the Florida Peninsula to the northern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, while males have a tendency to remain closer to the nesting beaches in the western gulf waters of Texas (USA), Tamaulipas, and Veracruz (Mexico).[13] It is rare for adult L. kempii to be found outside of the Gulf of Mexico and only 2-4%[17]:101 p. from the Atlantic are adults.[13][17][14][15]

Juveniles and sub-adults in contrast regularly migrate into the Atlantic Ocean and occupy the coastal waters of the continental shelf of North America from southern Florida to Cape Cod, Massachusetts and occasionally northward. Accidental and vagrant records are known with some regularity from throughout the northern Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea where the Gulf Stream is believed to play a significant role in their dispersal. Confirmed records from Newfoundland to Venezuela in the west; to Ireland, the Netherlands, Malta in the Mediterranean, and numerous localities in between are known in the east, although >95% of these involve juveniles or sub-adults.[17]:101 p. Several reports from the African coast from Morocco to Cameroon involve unverified specimens and may include misidentified Lepidochelys olivacea.[13][17][14][15]

Feeding and life history

Feeding

Kemp's ridley turtle feeds on mollusks, crustaceans, jellyfish, fish, algae or seaweed, and sea urchins. Juvenile Kemp's ridleys primarily feed on crabs.[18]

Life history

Most females return each year to a single beach—Rancho Nuevo in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas—to lay eggs. The females arrive in large groups of hundreds or thousands in nesting aggregations called arribadas, which is a Spanish word for "arrivals".[19][20]

Juvenile turtles tend to live in floating sargassum seaweed beds for their first years.[12] Then they range between northwest Atlantic waters and the Gulf of Mexico while growing into maturity.

They reach sexual maturity at the age of 10–12.[9]

This is the only species that nests primarily during the day, with 95% of all nesting occurring in Mexico in the state of Tamaulipas.[21] The nesting season for these turtles is April to August. They nest mostly on a 16-mile beach in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas and on Padre Island in the US state of Texas, and elsewhere on the Gulf coast. They mate offshore. Gravid females land in groups on beaches in what is commonly called an arribada[12] or mass nesting. They prefer areas with dunes or, secondarily, swamps. The estimated number of nesting females in 1947 was 89,000, but shrank to an estimated 7,702 by 1985.[22] Females nest two or three times during a season, keeping 10 to 20 days between nestings. Incubation takes 45 to 70 days. On average, around 110 eggs are in a clutch. The hatchlings' sex is decided by the temperature in the area during incubation. If the temperature is below 29.5 °C, the offspring will be mainly male.

.jpg.webp) Hatchling

Hatchling Hatchling

Hatchling.jpg.webp) Juvenile turtle

Juvenile turtle Adult turtle nesting

Adult turtle nesting Nesting female returning to sea

Nesting female returning to sea Deceased adult

Deceased adult

Conservation

Egg harvesting and pouching first depleted the numbers of Kemp's ridley sea turtles,[17] but today, major threats include habitat loss, pollution, and entanglement in shrimping nets.

Efforts to protect L. kempii began in 1966 when Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Biologico-Pesqueras [National Institute of Biological-Fisheries Research] sent biologists Hunberto Chávez, Martin Contreras, and Eduardo Hernondez to the coast of southern Tamaulipas, Mexico to survey and instigate conservation plans.[23] Kemp's ridley turtle was first listed under the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1970[24] on December 2, 1970, and subsequently under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973. In 1977 an informal, bi-national multi-agency The Kemp's Ridley Working Group first met to develop a recovery plan.[23] A binational recovery plan was developed in 1984, and revised in 1992. A draft public review draft of the second revision was published by NOAA Fisheries in March 2010.[25] This revision includes an updated threat assessment.[26]

One mechanism used to protect turtles from fishing nets is the turtle excluder device (TED). Because the biggest danger to the population of Kemp's ridley sea turtles is shrimp trawls, the device is attached to the shrimp trawl. It is a grid of bars with an opening at the top or bottom, fitted into the neck of the shrimp trawl. It allows small animals to slip through the bars and be caught while larger animals, such as sea turtles, strike the bars and are ejected, thus avoiding possible drowning.

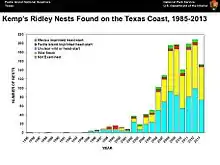

In September 2007, Corpus Christi, Texas, wildlife officials found a record of 128 Kemp's ridley sea turtle nests on Texas beaches, including 81 on North Padre Island (Padre Island National Seashore) and four on Mustang Island. The figure was exceeded in each of the following 7 years (see graph to 2013, provisional figures for 2014 as at July, 118.[27]). Wildlife officials released 10,594 Kemp's ridley hatchlings along the Texas coast that year. The turtles are popular in Mexico, as boot material and food.[28]

In July 2020, five rehabilitated turtles were released back in to Cape Cod with satellite tracking devices. to monitor their wellbeing.[29] A 2020 rescue mission to save 30 turtles from the freezing seas of Cape Cod was delayed by weather and technical issues, spurring a temporary rescue mission en-route between Massachusetts and New Mexico. The Tennessee Aquarium offered overnight shelter and care and the turtles were eventually released to the sea.[30]

Oil spills

Some Kemp's ridleys were airlifted from Mexico after the 1979 blowout of the Ixtoc 1 rig, which spilled millions of gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

Since April 30, 2010, 10 days after the accident on the Deepwater Horizon, 156 sea turtle deaths were recorded; most were Kemp's ridleys. Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries biologists and enforcement agents rescued Kemp's ridleys in Grand Isle.[31] "Most" of the 456 oiled turtles that were rescued, cleaned, and released by US Fish and Wildlife Service were Kemp's ridleys.[32]

Of the endangered marine species frequenting Gulf waters, only Kemp's ridley relies on the region as its sole breeding ground.[33]

As part of the effort to save the species from some of the effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, scientists took nests and incubated them elsewhere; 67 eggs were collected from a nest along the Florida Panhandle on June 26, 2010, and brought to a temperature-controlled warehouse at NASA's Kennedy Space Center, where 56 hatched, and 22 were released on 11 July 2010.[34]

The overall plan was to collect eggs from about 700 sea turtle nests, incubate them, and release the young on beaches across Alabama and Florida over a period of months.[34][35] Eventually, 278 nests were collected, including only a few Kemp's ridley nests.[36]

References

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter. (2007). Checklist of Chelonians of the World. Vertebrate Zoology 57 (2): 149-368. (Lepidochelys kempii, pp. 168-169).

- Rhodin AG, van Dijk PP, Iverson JB, Shaffer HB (2010). Rhodin AG, Pritchard PC, van Dijk PP, Saumure AR, Buhlmann KA, Iverson JB, Mittermeier RA (eds.). "Turtles of the World: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy and Synonymy" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. Chelonian Research Foundation and the Turtle Taxonomy Working Group of IUCN Species Survival Commission: 85–164. doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v3.2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Lepidochelys kempii, p. 139).

- Dundee, Harold A. (2001). "The Etymological Riddle of the Ridley Sea Turtle". Marine Turtle Newsletter. 58: 10–12. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Help Endangered Animals - Ridley Turtles. Gulf Office of the Sea Turtle Restoration Project. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- Philips, Pamela (September 1988). The Great Ridley Rescue. Mountain Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-87842-229-3.

- Conant R (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Second Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. xviii + 429 pp. + Plates 1-48. ISBN 0-395-19979-4 (hardcover), ISBN 0-395-19977-8 (paperback). (Lepidochelys kempi, pp. 75-76 + Plate 11).

- "Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtles, Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle Pictures, Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle Facts". National Geographic. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- Chatterji, RM; Hutchinson, MN; Jones, MEH (2020). "Redescription of the skull of the Australian flatback sea turtle, Natator depressus, provides new morphological evidence for phylogenetic relationships among sea turtles (Chelonioidea)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa071.

- Jones, MEH; Werneburg, I; Curtis, N; Penrose, RN; O'Higgins, P; Fagan, M; Evans, SE (2012). "The head and neck anatomy of sea turtles (Cryptodira: Chelonioidea) and skull shape in Testudines". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e47852. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747852J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047852. PMC 3492385. PMID 23144831.

- "Kemp's Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) - Office of Protected Resources - NOAA Fisheries". NOAA Fisheries. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Morreale, Stephen J., pamrls T. Plotkin, Donna J. Shaver, and Heather J. Kalb. 2007. Adult Migration and Habitat Utilization: Ridley Turtles in the Element. 213-229 pp. In Pamela T. Plotkin (editor). Biology and Conservation of Ridley Sea Turtles. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. x, 356 pp. ISBN 978-0-8018-86119

- Wilson, Robert V. and George R. Zug. 1991. Lepidochelys kempii. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. 509.1-509.8 pp.

- Iverson, John B. 1992. A Revised Checklist with Distribution Maps of the Turtles of the World. Green Nature Books. Homestead Florida. 363 pp. ISBN 1-888089-23-7

- Fritts, T. H., W. Hoffman, and M. A. McGehee. 1983. The distribution and abundance of marine turtles in the Gulf of Mexico and nearby Atlantic waters. Journal of Herpetology 17: 327-344.

- Ernst, Carl H. and Jeffrey E. Lovich. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada (2nd. ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. xii, 827 pp. ISBN 978-0-8018-9121-2

- Burke VJ, Morreale SJ, Standora EA (1994). "Diet of the Kemp's ridley sea turtle, Lepidochelys kempii, in New York waters". NOAA NMFS Fishery Bulletin. Retrieved Dec 20, 2015.

- Pritchard, Peter (1969). "Studies of the systematics and reproduction of the genus Lepidochelys ". Ph.D. Dissertation – via University of Florida, Gainesville.

- Plotkin, Pamela (2007). Biology and Conservation of Ridley Sea Turtles. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780801886119 – via Google Books.

- "Kemp's Ridleys". SEE Turtles. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- "Sea Turtle Recovery Project". National Park Service. March 9, 2010. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010.

- Heppell, Selina S., Patrick M. Burchfield, and Luis Jaine Peña. 2007. Kemp's Ridley Recovery: How Far Have We Come, and Where Are We Headed? 325-335 pp. In Pamela T. Plotkin (editor). Biology and Conservation of Ridley Sea Turtles. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. x, 356 pp. ISBN 978-0-80188611-9

- "Endangered Species Act (ESA) :: NOAA Fisheries". Nmfs.noaa.gov. 2013-08-08. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- "Draft Bi-National Recovery Plan for the Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)" (PDF). nmfs.noaa.gov. Secretariat of Environment & Natural Resources Mexico, U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Department of Interior. September 19, 1984.

- "2010 Threats Assessment, NOAA Fisheries".

- "Current Sea Turtle Nesting Season". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015.

- Yahoo.com, Endangered turtle nests found in Texas

- Engl, New; Aquarium. "A Safe Send-Off for Sea Turtles". New England Aquarium. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- Fazio, Marie (2020-11-29). "Effort to Rescue Endangered Turtles Becomes a Thanksgiving Odyssey". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-11-30.

- "Sea Turtles recovered from Oil Spill Gulf of Mexico". via Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. May 31, 2007. Archived from the original on October 23, 2016.

- Masti, Ramit (June 1, 2011). "Nesting turtles give clues on oil spill's impact". Fox News. Associated Press. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- Kaufman, Leslie (May 18, 2010). "Gulf Oil Again Imperils Sea Turtle". The New York Times.

- Macintosh, Zoe (July 16, 2010). "NASA Rescues Baby Sea Turtles Threatened by Gulf Oil Spill". Space.com. Purch. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- , centurylink.net, July 15, 2010 Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "NASA's turtle egg rescue from Gulf oil spill is deemed a success". NOLA. Associated Press. September 8, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

Further reading

- Garman S. (1880). On certain Species of Chelonioidæ. Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool., Harvard College 6 (6): 123–126. (Thalassochelys kempii, new species, pp. 123–124).

- Marine Turtle Specialist Group (1996). "Lepidochelys kempii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T11533A3292342. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T11533A3292342.en. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is critically endangered and the criteria used

- Sizemore, Evelyn (2002). The Turtle Lady: Ila Fox Loetscher of South Padre. Plano, Texas: Republic of Texas Press. p. 220. ISBN 1-55622-896-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lepidochelys kempii. |

- Profile from the OBIS-SEAMAP project of the Ocean Biogeographic Information System

- Turtle Trax.org: Kemp's ridley sea turtle Profile

- Coastal Research and Education Society of Long Island wiki Information on Kemp's ridley sea turtle

- Information from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

- Texas Parks & Wildlife Dept. — Kemp's ridley sea turtle