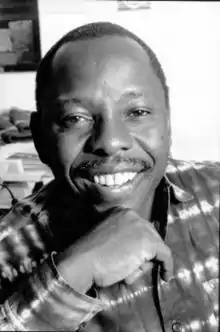

Ken Saro-Wiwa

Kenule Beeson "Ken" Saro-Wiwa (10 October 1941 – 10 November 1995) was a Nigerian writer, television producer, environmental activist, and winner of the Right Livelihood Award for "exemplary courage in striving non-violently for civil, economic and environmental rights" and the Goldman Environmental Prize.[1] Saro-Wiwa was a member of the Ogoni people, an ethnic minority in Nigeria whose homeland, Ogoniland, in the Niger Delta has been targeted for crude oil extraction since the 1950s and which has suffered extreme environmental damage from decades of indiscriminate petroleum waste dumping.[2] Initially as spokesperson, and then as president, of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), Saro-Wiwa led a nonviolent campaign against environmental degradation of the land and waters of Ogoniland by the operations of the multinational petroleum industry, especially the Royal Dutch Shell company.[3] He was also an outspoken critic of the Nigerian government, which he viewed as reluctant to enforce environmental regulations on the foreign petroleum companies operating in the area.[4]

Ken Saro-Wiwa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 10 October 1941 |

| Died | 10 November 1995 (aged 54) Port Harcourt, Nigeria |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Occupation | writer |

| Movement | Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People |

| Awards | Right Livelihood Award Goldman Environmental Prize |

At the peak of his non-violent campaign, he was tried by a special military tribunal for allegedly masterminding the gruesome murder of Ogoni chiefs at a pro-government meeting, and hanged in 1995 by the military dictatorship of General Sani Abacha. His execution provoked international outrage and resulted in Nigeria's suspension from the Commonwealth of Nations for over three years.[5]

Biography

Early life

Born Kenule Tsaro-Wiwa, Saro-Wiwa was the son of Chief Jim Wiwa, a forest ranger that held a title in the Nigerian chieftaincy system, and his third wife Widu. He officially changed his name to Saro-Wiwa after the Nigerian Civil war.[6] He was married to Maria Saro Wiwa.[7] His father's hometown was the village of Bane, Ogoniland, whose residents speak the Khana dialect of the Ogoni language. Saro-Wiwa spent his childhood in an Anglican home and eventually proved himself to be an excellent student; he received primary education at a Native Authority school in Bori, [8] then attended secondary school at Government College Umuahia. A distinguished student, Saro-Wiwa was captain of the table tennis team and amassed school prizes in history and English.[9] On completion of secondary education, he obtained a scholarship to study English at the University of Ibadan. At Ibadan, he plunged into academic and cultural interests, he won departmental prizes in 1963 and 1965 and worked for a drama troupe.[10] The travelling drama troupe performed in Kano, Benin, Ilorin and Lagos and collaborated with the Nottingham Playhouse theatre group that included a young Judi Dench.[10] He briefly became a teaching assistant at the University of Lagos and later at University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Saro-Wiwa was an African literature lecturer in Nsukka when the Civil war broke out, he supported the Federal Government and had to leave the region for his hometown of Bori. On his journey to Port-Harcourt, he witnessed the multitudes of refugees returning to the East, a scene he described as a "sorry sight to see".[11] Three days after his arrival, nearby Bonny fell to federal troops. He and his family then stayed in Bonny, he travelled back to Lagos and took a position at the University of Lagos which did not last long as he was called back to Bonny.

He was called back to become the Civilian Administrator for the port city of Bonny in the Niger Delta and during the Nigerian Civil War positioned himself as an Ogoni leader dedicated to the Federal cause. [12]He followed his job as an administrator with an appointment as a commissioner in the old Rivers State. His best known novel, Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English, tells the story of a naive village boy recruited to the army during the Nigerian Civil War of 1967 to 1970, and intimates the political corruption and patronage in Nigeria's military regime of the time. Saro-Wiwa's war diaries, On a Darkling Plain, document his experience during the war. He was also a successful businessman and television producer. His satirical television series, Basi & Company, was wildly popular, with an estimated audience of 30 million.[13]

In the early 1970s, Saro-Wiwa served as the Regional Commissioner for Education in the Rivers State Cabinet, but was dismissed in 1973 because of his support for Ogoni autonomy. In the late 1970s, he established a number of successful business ventures in retail and real estate, and during the 1980s concentrated primarily on his writing, journalism and television production. In 1977, he became involved in the political arena running as the candidate to represent Ogoni in the Constituent Assembly. Saro-Wiwa lost the election in a narrow margin.[14] It was during this time he had a fall out with his friend Edwards Kobani.

His intellectual work was interrupted in 1987 when he re-entered the political scene, having been appointed by the newly installed dictator Ibrahim Babangida to aid the country's transition to democracy. But Saro-Wiwa soon resigned because he felt Babangida's supposed plans for a return to democracy were disingenuous. Saro-Wiwa's sentiments were proven correct in the coming years, as Babangida failed to relinquish power. In 1993, Babangida annulled Nigeria's general elections that would have transferred power to a civilian government, sparking mass civil unrest and eventually forcing him to step down, at least officially, that same year.[15]

Works

Saro-Wiwa's works include TV, drama and prose writing. His earlier works from 1970s to 1980s are mostly satirical displays that portrays a counter-image of Nigerian society[16] but his later writings were more inspired by political dimensions such as environmental and social justice than satire.

Transistor Radio, one of his best known plays[17] was written for a revue during his university days at Ibadan but still resonated well with Nigerian society and was adapted into a television series. Some of his works drew inspiration from the play. In 1972, a radio version of the play was produced and in 1985, he produced, Basi and Company, a successful screen adaption of the play. Saro-Wiwa included the play in Four Farcical Plays and Basi and Company: Four Television Plays. Basi and company, an adaptation of Transistor Radio ran on television from 1985 to 1990. A farcical comedy,[18] the show chronicles city life and is anchored by the protagonist, Basi, a resourceful and street wise character looking for ways to achieve his goal of obtaining millions which always ends to become an illusive mission.

In 1985, the Biafran Civil War novel Sozaboy was published. The protagonist's language was written in nonstandard English or what Saro-Wiwa called "Rotten English", a hybrid language of pidgin English, standard English and broken English.[19]

Activism

In 1990, Saro-Wiwa began devoting most of his time to human rights and environmental causes, particularly in Ogoniland. He was one of the earliest members of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), which advocated for the rights of the Ogoni people. The Ogoni Bill of Rights, written by MOSOP, set out the movement's demands, including increased autonomy for the Ogoni people, a fair share of the proceeds of oil extraction, and remediation of environmental damage to Ogoni lands. In particular, MOSOP struggled against the degradation of Ogoni lands by Royal Dutch Shell.[20]

In 1992, Saro-Wiwa was imprisoned for several months, without trial, by the Nigerian military government.

Saro-Wiwa was Vice Chair of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) General Assembly from 1993 to 1995.[21] UNPO is an international, nonviolent, and democratic organisation (of which MOSOP is a member). Its members are indigenous peoples, minorities, and unrecognised or occupied territories who have joined together to protect and promote their human and cultural rights, to preserve their environments and to find nonviolent solutions to conflicts which affect them.

In January 1993, MOSOP organised peaceful marches of around 300,000 Ogoni people – more than half of the Ogoni population – through four Ogoni urban centres, drawing international attention to their people's plight. The same year the Nigerian government occupied the region militarily.[22]

Arrest and execution

Saro-Wiwa was arrested again and detained by Nigerian authorities in June 1993 but was released after a month.[23] On 21 May 1994 four Ogoni chiefs (all on the conservative side of a schism within MOSOP over strategy) were brutally murdered. Saro-Wiwa had been denied entry to Ogoniland on the day of the murders, but he was arrested and accused of inciting them. He denied the charges but was imprisoned for over a year before being found guilty and sentenced to death by a specially convened tribunal. The same happened to eight other MOSOP leaders who, along with Saro-Wiwa, became known as the Ogoni Nine.[24]

Some of the defendants' lawyers resigned in protest against the alleged rigging of the trial by the Abacha regime. The resignations left the defendants to their own means against the tribunal, which continued to bring witnesses to testify against Saro-Wiwa and his peers. Many of these supposed witnesses later admitted that they had been bribed by the Nigerian government to support the criminal allegations. At least two witnesses who testified that Saro-Wiwa was involved in the murders of the Ogoni elders later recanted, stating that they had been bribed with money and offers of jobs with Shell to give false testimony, in the presence of Shell's lawyer.[25]

The trial was widely criticised by human rights organisations and, half a year later, Ken Saro-Wiwa received the Right Livelihood Award for his courage, as well as the Goldman Environmental Prize.[26]

On 8 November 1995, a military ruling council upheld the death sentences. The military government then immediately moved to carry them out. The prison in Port Harcourt was selected as the place of execution. Although the government wanted to carry out the sentences immediately, it had to wait two days for a makeshift gallows to be built. Within hours of the sentences being upheld, nine coffins were taken to the prison, and the following day a team of executioners was flown in from Sokoto to Port Harcourt.[27]

On 10 November 1995, Saro-Wiwa and the rest of the Ogoni Nine were taken from the army base where they were being held to Port Harcourt prison. They were told that they were being moved to Port Harcourt because it was feared that the army base they were being held in might be attacked by Ogoni youths. The prison was heavily guarded by riot police and tanks, and hundreds of people lined the streets in anticipation of the executions. After arriving at Port Harcourt prison, Saro-Wiwa and the others were herded into a single room and their wrists and ankles were shackled. They were then led one by one to the gallows and executed by hanging, with Saro-Wiwa being the first. It took five tries to execute him due to faulty equipment.[27] His last words were "Lord take my soul, but the struggle continues." After the executions, the bodies were taken to the Port Harcourt Cemetery under armed guard and buried.[28][29] Anticipating disturbances as a result of the executions, the Nigerian government deployed tens of thousands of troops and riot police to two southern provinces and major oil refineries around the country. The Port Harcourt Cemetery was surrounded by soldiers and tanks.[30][27]

The executions provoked a storm of international outrage. The United Nations General Assembly condemned the executions in a resolution which passed by a vote of 101 in favor to 14 against and 47 abstentions.[31] The European Union condemned the executions, which it called a "cruel and callous act", and imposed an arms embargo on Nigeria.[32][33] The United States recalled its ambassador from Nigeria, imposed an arms embargo on Nigeria, and slapped travel restrictions on members of the Nigerian military regime and their families.[34] The United Kingdom recalled its high commissioner in Nigeria, and British Prime Minister John Major called the executions "judicial murder."[35] South Africa took a primary role in leading international criticism, with President Nelson Mandela urging Nigeria's suspension from the Commonwealth of Nations. Zimbabwe and Kenya also backed Mandela, with Kenyan President Daniel arap Moi and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe backing Mandela's demand to suspend Nigeria's Commonwealth membership, but a number of other African leaders criticized the suggestion. Nigeria's membership in the Commonwealth of Nations was ultimately suspended, and Nigeria was threatened with expulsion if it did not transition to democracy in two years. The US and British governments also discussed the possibility of an oil embargo backed by a naval blockade of Nigeria.[32][36]

In his 1989 short story "Africa Kills Her Sun", Saro-Wiwa in a resigned, melancholic mood, foreshadowed his own execution.[37][38][39]

Ken Saro-Wiwa Foundation

The foundation was established in 2017 to work towards improved access to basic resources such as electricity and Internet for entrepreneurs in Port Harcourt.[40] The association founded the Ken Junior Award, named for Saro-Wiwa's son Ken Wiwa, who died in October 2016.[41] The award is presented to innovative start-up technology companies in Port Harcourt.[40]

Family lawsuits against Royal Dutch Shell

Beginning in 1996, the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), Earth Rights International (ERI), Paul Hoffman of Schonbrun, DeSimone, Seplow, Harris & Hoffman and other human rights attorneys have brought a series of cases to hold Shell accountable for alleged human rights violations in Nigeria, including summary execution, crimes against humanity, torture, inhumane treatment and arbitrary arrest and detention. The lawsuits are brought against Royal Dutch Shell and Brian Anderson, the head of its Nigerian operation.[42]

The cases were brought under the Alien Tort Statute, a 1978 statute giving non-US citizens the right to file suits in US courts for international human rights violations, and the Torture Victim Protection Act, which allows individuals to seek damages in the US for torture or extrajudicial killing, regardless of where the violations take place.

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York set a trial date of June 2009. On 9 June 2009 Shell agreed to an out-of-court settlement of US$15.5 million to victims' families. However, the company denied any liability for the deaths, stating that the payment was part of a reconciliation process.[43] In a statement given after the settlement, Shell suggested that the money was being provided to the relatives of Saro-Wiwa and the eight other victims, to cover the legal costs of the case and also in recognition of the events that took place in the region.[44] Some of the funding is also expected to be used to set up a development trust for the Ogoni people, who inhabit the Niger Delta region of Nigeria.[45] The settlement was made just days before the trial, which had been brought by Ken Saro-Wiwa's son, was due to begin in New York.[44]

Legacy

Saro-Wiwa's death provoked international outrage and the immediate suspension of Nigeria from the Commonwealth of Nations, as well as the calling back of many foreign diplomats for consultation. The United States and other countries considered imposing economic sanctions. Other tributes to him include:

Artwork and memorials

- A memorial to Saro-Wiwa was unveiled in London on 10 November 2006 by London organisation Platform.[46] It consists of a sculpture in the form of a bus and was created by Nigerian-born artist Sokari Douglas Camp. It toured the UK the following year.

Awards

- The Association of Nigerian Authors is a sponsor of the Ken Saro-Wiwa Prize for Prose.[47]

- He is named a Writer hero by The My Hero Project.[48]

Literature

- Saro-Wiwa's execution is quoted and used as an inspiration for Beverley Naidoo's novel The Other Side of Truth (2000).

- Richard North Patterson published a novel, Eclipse (2009), based upon the life and death of Ken Saro-Wiwa.[49]

Kenule Beeson Saro-Wiwa Polytechnic

- The Governor of Rivers State, Ezenwo Nyesom Wike has renamed the Rivers State Polytechnic after Ken Saro-Wiwa.

Maynooth University and Ken Saro-Wiwa

A collection of handwritten letters by Ken Saro-Wiwa were donated to Maynooth University by Sister Majella McCarron, also in the collection are 27 poems, recordings of visits and meetings with family and friends after Saro-Wiwa's death, a collection of photographs and other documents.

The letters are now in the Digital Repository of Ireland (DRI).[50]

The Ken Saro-Wiwa Archive is housed in Special Collections at Maynooth University.[51]

Music

- The Italian band Il Teatro degli Orrori dedicated their song "A sangue freddo" ("In cold blood" – also the title track of their second album) to the memory of Ken Saro-Wiwa.

- The Finnish band Ultra Bra dedicated their song "Ken Saro-Wiwa on kuollut" ("Ken Saro-Wiwa is dead") to the memory of Ken Saro-Wiwa.[52]

- Saro-Wiwa's execution inspired the song "Rational" by Canadian band King Cobb Steelie.[53]

- Rapper Milo shouts Ken Saro-Wiwa out on the song Zen Scientist.

- The punk rock band Anti-Flag talk about him in their song Mumia's Song.

- The Nigerian singer Nneka makes reference to Ken Saro-Wiwa in her song[54] and music video[55] "Soul is Heavy".[56]

Films

Aki Kaurismäki's 1996 film Drifting Clouds includes a scene where the main character hears of Saro-Wiwa's death from the television news.[57]

Ken Saro-Wiwa lives on! - direct by Elisa Dassoler (BRAZIL). 2017, color. 82 min. The film is available on the internet.

Streets

- Amsterdam has named a street after Saro-Wiwa, the Ken Saro-Wiwastraat.

Personal life

Saro-Wiwa and his wife Maria had five children, who grew up with their mother in the United Kingdom while their father remained in Nigeria. They include Ken Wiwa and Noo Saro-Wiwa, both journalists and writers, and Noo's twin Zina Saro-Wiwa, a journalist and filmmaker.[58][59] In addition, Saro-Wiwa had two daughters (Singto & Adele) with another woman.[58] He also had another son, Kwame Saro-Wiwa, who was only 1 year old when his father was executed.[60]

Biographies

- Canadian author J. Timothy Hunt's The Politics of Bones (September 2005), published shortly before the 10th anniversary of Saro-Wiwa's execution, documented the flight of Saro-Wiwa's brother Owens Wiwa, after his brother's execution and his own imminent arrest, to London and then on to Canada, where he is now a citizen and continues his brother's fight on behalf of the Ogoni people. Moreover, it is also the story of Owens' personal battle against the Nigerian government to locate his brother's remains after they were buried in an unmarked mass-grave.

- Ogoni's Agonies: Ken Saro Wiwa and the Crisis in Nigeria (1998), edited by Abdul Rasheed Naʾallah, provides more information on the struggles of the Ogoni people [61]

- Onookome Okome's book, Before I Am Hanged: Ken Saro-Wiwa—Literature, Politics, and Dissent (1999)[62] is a collection of essays about Wiwa

- In the Shadow of a Saint: A Son's Journey to Understanding His Father's Legacy, was written by his son Ken Wiwa.

- Saro-Wiwa's own diary, A Month and a Day: A Detention Diary, was published in January 1995, two months after his execution.

- InLooking for Transwonderland - Travels in Nigeria, his daughter Noo Saro-Wiwa tells the story of her return to Nigeria years after her father's murder.

Bibliography

- —— (1973). Tambari. Ikeja: Longman Nigeria. ISBN 978-0-582-60135-2.

- —— (1985). Songs in a Time of War. Port Harcourt: Saros. ISBN 978-978-2460-00-4.

- —— (1986). Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English. Port Harcourt: Saros. ISBN 978-978-2460-02-8.

- —— (1987). Mr. B. Port Harcourt: Saros. ISBN 978-1-870716-01-7.

- —— (1987). Basi and Company: A Modern African Folktale. Port Harcourt, Nigeria: Saros. ISBN 978-1-870716-00-0.

- —— (1987). Basi and Company: Four Television Plays. Port Harcourt, Nigeria: Saros. ISBN 978-1-870716-03-1.

- —— (1988). Prisoners of Jebs. Port Harcourt [u.a.]: Saros. ISBN 978-1-870716-02-4.

- —— (1989). Adaku & Other Stories. London: Saros International. ISBN 1-870716-10-8.

- —— (1989). Four Farcical Plays. London: Saros International. ISBN 1-870716-09-4.

- —— (1989). On a Darkling Plain: An Account of the Nigerian Civil War. Epsom: Saros. ISBN 1-870716-11-6.

- —— (1991). Mr B Is Dead. London, Lagos, Port Harcourt: Saros International Publishers. ISBN 1-870716-14-0.

- —— (1992). Genocide in Nigeria: The Ogoni Tragedy. London: Saros. ISBN 1-870716-22-1.

- —— (1995). A Forest of Flowers: Short Stories. Burnt Mill, Harlow, Essex, England: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-27320-7.

- —— (1995). A Month and a Day: A Detention Diary. New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-025914-8.

- —— (1996). Lemona's Tale. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-026086-1.

- ——; Adinoyi-Ojo, Onukaba (2005). A Bride for Mr B. London: Saros. ISBN 1-870716-26-4.

See also

References

- "@around9ja Instagram profile with posts and stories - Picuki.com". www.picuki.com. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Wetin you gatz know about Ken Saro-Wiwa". BBC News Pidgin. 11 November 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Ken Saro-Wiwa". www.fantasticfiction.com. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Environmentalist Leader - Ken Saro-Wiwa (1941-1995) - Green Practices - Forums - Tunza Eco Generation". tunza.eco-generation.org. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Editor. "Ken Saro-Wiwa (1941-1995)". Ogoni News. Retrieved 27 May 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Doron & Falola 2016, p. 35.

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/11/ken-saro-wiwa-widow-talks-execution-20-years-151110143101367.html

- Doron & Falola 2016, p. 36.

- Doron & Falola 2016, p. 39.

- Doron & Falola 2016, p. 41.

- Doron & Falola 2016, p. 50.

- Doron & Falola 2016, p. 43.

- Brooke, James (24 July 1987). "Enugu Journal; 30 Million Nigerians are Laughing at Themselves". The New York Times.

- Doron & Falola 2016, p. 64.

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. p. 356. ISBN 0195337700. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Davis et al. 2006, p. 269.

- Davis et al. 2006, p. 270.

- Davis et al. 2006, p. 273.

- 91

- "About Wiwa v. Shell". Wiwa family lawsuits against Royal Dutch Shell. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Clean the Niger Delta – 'We all stand before history', Ken Saro-Wiwa, 1995". UNPO. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Ken Saro Wiwa". Ken Saro Wiwa. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "The Life & Death of Ken Saro-Wiwa: The Struggle for Justice in the Niger Delta". adiama.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- Pilkington, Ed (9 June 2009). "Shell pays out $15.5m over Saro-Wiwa killing". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- Entine, Jon (18 June 2009). "Seeds of NGO Activism: Shell Capitulates in Saro-Wiwa Case". NGO Watch. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "Ken Saro-Wiwa". The Goldman Environmental Prize. 1995. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- https://apnews.com/b67c33cdb8573a29a2391d0754c0349b

- "Nigeria's Military Leaders Hang Playwright And 8 Other Activists". Deseretnews.com. Deseret News Publishing Company. 11 November 1995. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/it-took-five-tries-to-hang-saro-wiwa-1581703.html

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world-fury-as-nigeria-sends-writer-to-gallows-1581289.html

- https://www.un.org/press/en/1995/19951222.ga9046.html

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50892306

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/PESC_95_98

- https://apnews.com/0f5de90d3224dc88e8f9b807fd5206a3

- https://books.google.com/books?id=qz9BlWO7ExwC&pg=PA129

- http://www.ipsnews.net/1995/11/commonwealth-nigeria-suspended-with-a-two-year-stay-of-expulsion/

- "Review of Africa Kills Her 'Sun'". Qessays.

- "Africa Kills Her Sun Summary". eNotes.

- Ken Saro-Wiwa, Africa Kills Her Sun, p. 365.

- Asika, Obiageli (23 August 2017). "Apply Now: Ken Saro Wiwa Foundation Ken Junior Award For Innovation 2017". DailyDigest Nigeria. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Alexander Sewell. "Ken Saro-Wiwa Foundation award for innovation". SDN. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "Wiwa et al v. Royal Dutch Petroleum et al". Center for Constitutional Rights.

- "Shell settles Nigeria deaths case". BBC. 9 June 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- Mouawad, Jad (9 June 2009). "Shell to Pay $15.5 Million to Settle Nigerian Case". New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- Seib, Christine (9 June 2009). "Shell agrees $15.5m settlement over death of Saro-Wiwa and eight others". The Times. London. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- "Remembering Ken Saro-Wiwa". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- "2012 Association of Nigerian Authors [ANA] Prizes: CALL FOR ENTRIES". Kabura Zakama Randomised.

- "Ken Saro-Wiwa". The My Hero Project. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Richard North Patterson author interview". BookBrowse.com. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- "Digital Repository of Ireland".

- "Special Collections Maynooth University".

- Ultra Bra (1996), "Ken Saro-Wiwa on kuollut" on their album Vapaaherran elämää.

- King Cobb Steelie (1997), "Rational" on their album Junior Relaxer.

- "Soul Is Heavy song lyrics". Genius.com. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Nneka - Soul Is Heavy (Official Video)". Youtube.com. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Nneka (2011), "Soul is Heavy" on her album Soul Is Heavy.

- Austin, Thomas (2018). The Films of Aki Kaurismäki: Ludic Engagements. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 24. ISBN 978-150-13253-8-0.

- Henley, Jon (30 December 2011). "Nigerian activist Ken Saro-Wiwa's daughter remembers her father". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Berens, Jessica (28 May 2004). "'I've seen a different face of Nigeria'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- https://www.opendemocracy.net/ken-saro-wiwa-biodun-jefiyo/from-silence-would-be-treason-last-writings-of-ken-saro-wiwa

- Na'Allah, Abdul Rasheed (Editor) (1998). Ogoni's Agonies: Ken Saro Wiwa and the Crisis in Nigeria. Africa World Press. ISBN 0865436479.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Okome, Onookome (1999). Before I Am Hanged: Ken Saro-Wiwa—Literature, Politics, and Dissent. Africa World Press.

Sources

- Doron, Roy; Falola, Toyin (2016). Ken Saro-Wiwa. Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821422014.

- Davis, edited by Christine Matzke, Aderemi Raji-Oyelade, Geoffrey V.; Raji, Rami; Davis, Geoffrey; Ezenwa, Ohaeto (2006). Of minstrelsy and masks : the legacy of Ezenwa-Ohaeto in Nigerian writing. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 9042021683.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Ken Saro-Wiwa |

- "Standing Before History: Remembering Ken Saro-Wiwa" at PEN World Voices, sponsored by Guernica Magazine in New York City on 2 May 2009.

- "The perils of activism: Ken Saro-Wiwa" by Anthony Daniels

- Letter of protest published in the New York Review of Books shortly before Saro-Wiwa's execution.

- Ken Saro-Wiwa's son, Ken Wiwa, writes a letter on openDemocracy.net about the campaign to seek justice for his father in a lawsuit against Shell – "America in Africa: plunderer or part"

- The Ken Saro-Wiwa Foundation

- Remember Saro-Wiwa campaign

- PEN Centres honour Saro-Wiwa's memory – IFEX

- The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) 1995 Ogoni report

- Right Livelihood Award recipient

- The Politics of Bones, by J. Timothy Hunt

- Wiwa v. Shell trial information

- Ken Saro-Wiwa at Maynooth University

- Ken Saro-Wiwa at the Digital Repository of Ireland