Laryngectomy

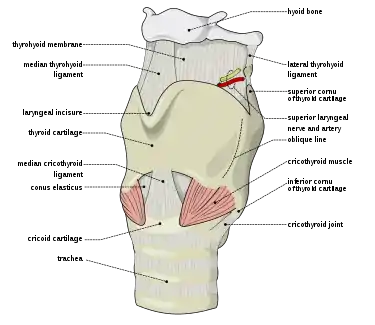

Laryngectomy is the removal of the larynx and separation of the airway from the mouth, nose and esophagus. In a total laryngectomy, the entire larynx is removed (including the vocal folds, hyoid bone, epiglottis, thyroid and cricoid cartilage and a few tracheal cartilage rings).[1] In a partial laryngectomy, only a portion of the larynx is removed. Following the procedure, the person breathes through an opening in the neck known as a stoma.[2] This procedure is usually performed by an ENT surgeon in cases of laryngeal cancer. Many cases of laryngeal cancer are treated with more conservative methods (surgeries through the mouth, radiation and/or chemotherapy). A laryngectomy is performed when these treatments fail to conserve the larynx or when the cancer has progressed such that normal functioning would be prevented. Laryngectomies are also performed on individuals with other types of head and neck cancer.[3] Post-laryngectomy rehabilitation includes voice restoration, oral feeding and more recently, smell and taste rehabilitation. An individual's quality of life can be affected post-surgery.[1]

| Laryngectomy | |

|---|---|

Anatomical changes following a laryngectomy | |

| ICD-9-CM | 30.2 30.3 30.4 |

| MeSH | D007825 |

| MedlinePlus | 007398 |

History

The first total laryngectomy was performed in 1873 by Theodor Billroth.[4][5] The patient was a 36 year old man with a subglottic squamous cell carcinoma. On November 27, 1873 Billroth performed a partial laryngectomy. Subsequent laryngoscopic examination in mid-December 1873 found tumor recurrence. On December 31, 1873 Billroth performed the first total laryngectomy. The patient recovered, and an artificial larynx was manufactured for him which enabled the patient to speak despite the removal of his vocal cords.

Older references credit a Patrick Watson of Edinburgh with the first laryngectomy in 1866,[6][7] but this patient's larynx was only excised after death.

The first artificial larynx was constructed by Johann Nepomuk Czermak in 1869. Vincenz Czerny developed an artificial larynx which he tested in dogs in 1870.[8]

Incidence/Prevalence

According to the GLOBOCAN 2018 estimates of cancer incidence and mortality produced by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, there were 177,422 new cases of laryngeal cancer worldwide in 2018 (1.0% of the global total.) Among worldwide cancer deaths, 94,771 (1.0%) were due to laryngeal cancer. [9]

In 2019 it is estimated that there will be 12,410 new laryngeal cancer cases in the United States, (3.0 per 100,000).[10] The number of new cases decreases every year at a rate of 2.4%,[10] and this is believed to be related to decreased cigarette smoking in the general population.[11] The number of laryngectomies performed each year in the U.S. has been declining at an even faster rate[12] due to the development of less invasive techniques.[13] A study using the National Inpatient Sample found that there were 8,288 total laryngectomy cases performed in the US between 1998 and 2008, and that hospitals performing total laryngectomy decreased by 12.3 per year.[14] As of 2013, one reference estimates that there are 50,000 to 60,000 laryngectomees in the US.[13]

Identification

To determine the severity/spread of the laryngeal cancer and the level of vocal fold function, indirect laryngoscopies using mirrors, endoscopies (rigid or flexible) and/or stroboscopies may be performed.[1] Other methods of visualization using CT scans, MRIs and PET scans and investigations of the cancer through biopsy can also be completed. Acoustic observations can also be utilized, where certain laryngeal cancer locations (e.g. at the level of the glottis) can cause an individual's voice to sound hoarse.[1]

Examinations are used to determine the tumor classification (TNM classification) and the stage (1-4) of the tumor. The increasing classifications from T1 to T4 indicates the spread/size of the tumor and provides information on which surgical intervention is recommended, where T1-T3 (smaller tumors) may require partial laryngectomies and T4 (larger tumors) may require complete laryngectomies.[1] Radiation and/or chemotherapy may also be used.

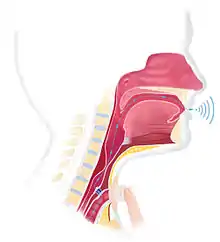

The airways and ventilation after laryngectomy

The anatomy and physiology of the airways change after laryngectomy. After a total laryngectomy, the individual breathes through a stoma where the tracheostomy has created an opening in the neck. There is no longer a connection between the trachea and the mouth and nose. These individuals are termed total neck breathers. After a partial laryngectomy, the individual breathes mainly through the stoma, but a connection still exists between the trachea and upper airways such that these individuals are able to breathe air through the mouth and nose. They are therefore termed partial neck breathers. The extent of breathing through the upper airways in these individuals varies and a tracheostomy tube is present in many of them. Ventilation and resuscitation of total and partial neck breathers is performed through the stoma. However, for these individuals, the mouth should be kept closed and the nose should be sealed to prevent air escape during resuscitation.[15]

Complications

Different types of complications can follow total laryngectomy. The most frequent postoperative complication is pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF), characterized by an abnormal opening between the pharynx and the trachea or the skin resulting in the leaking of saliva outside of the throat.[16][17] This complication, which requires feeding to be completed via nasogastric tube, increases morbidity, length of hospitalization, and level of discomfort, and may delay rehabilitation.[18] Up to 29% of persons who undergo total laryngectomy will be affected by PCF.[16] Various factors have been associated with an increased risk of experiencing this type of complication. These factors include anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, poor nutrition, hepatic and renal dysfunction, preoperative tracheostomy, smoking, alcohol use, older age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and localization and stage of cancer.[16][17] However, the installation of a free-flap has been shown to significantly reduce the risks of PCF.[16] Other complications such as wound infection, dehiscence and necrosis, bleeding, pharyngeal and stomal stenosis, and dysphagia have also been reported in fewer cases.[16][17]

Rehabilitation

Voice restoration

Total laryngectomy results in the removal of the larynx, an organ essential for natural sound production.[19] The loss of voice and of normal and efficient verbal communication is a negative consequence associated with this type of surgery and can have significant impacts on the quality of life of these individuals.[19][20] Voice rehabilitation is an important component of the recovery process following the surgery. Technological and scientific advances over the years have led to the development of different techniques and devices specialized in voice restoration.

The desired method of voice restoration should be selected based on each individual’s abilities, needs, and lifestyle.[21] Factors that affect success and candidacy for any chosen voice restoration method could include: cognitive ability, individual physiology, motivation, physical ability, and pre-existing medical conditions.[22][23]

Pre and post-operative sessions with a speech-language pathologist (SLP) are often part of the treatment plan for people undergoing a total laryngectomy.[24] Pre-operative sessions would likely involve counselling on the function of the larynx, the options for post-op voice restoration, and managing expectations for outcomes and rehabilitation.[22] Post-operative therapy sessions with an SLP would aim to help individuals learn to vocalize and care for their new voice prosthesis as well as refine their use of speech depending on the chosen method of voice restoration.[24]

Available methods for voice restoration:

- For tracheoesophageal speech, a voice prosthesis is placed in the tracheo-oesophageal puncture (TEP) created by the surgeon. The voice prosthesis is a one-way air valve that allows air to pass from the lungs/trachea to the esophagus when the stoma is covered, where the redirected air vibrates the esophageal tissue to produce a hoarse voice.[25] The TEP and voice prosthesis combination allows individuals post-laryngectomy to have a voice to speak, while also avoiding aspiration of saliva, food or other liquids.[20] Tracheoesophageal speech is considered more natural sounding than esophageal speech, but voice quality differs from person to person.[1]

- For speech using an electrolarynx, an electrolarynx is an external device that is placed against the neck and creates vibration that the speaker then articulates. The sound has been characterized as mechanical and robotic.

- For esophageal speech, the speaker pushes air into the esophagus and then pushes it back up, articulating speech sounds to speak. This method is time-consuming and difficult to learn and is less frequently used by laryngectomees.[26]

- For larynx transplants, a larynx from a cadaver donor is used as a replacement. This option is the most recent and is still very rare.[27]

For individuals using tracheoesophageal or esophageal speech, botulinum toxin may be injected to improve voice quality when spasms or increased tone (hypertonicity) is present at the level of the pharyngoesophageal segment muscles.[28] The amount of botulinum toxin administered unilaterally into two or three sites along the pharyngoesophageal segment varies from 15 to 100 units per injection. Positive voice improvements are possible after a single injection, however outcomes are variable. Dosages may need to be re-administered (individual-dependent) after a number of months, where effective results are expected to last for about 6 to 9 months.[28]

Oral feeding

The laryngectomy surgery results in anatomical and physiological changes in the larynx and surrounding structures. Consequently, swallowing function can undergo changes as well, compromising the patient's oral feeding ability and nutrition.[29] Patients may experience distress, frustration, and reluctance to eat out due to swallowing difficulties.[30] Despite the high prevalence of post-operative swallowing difficulties in the first days following the laryngectomy, most patients recover swallowing function within 3 months.[31] Laryngectomy patients do not aspirate due to the structural changes in the larynx, but they may experience difficulty swallowing solid food. They may also experience changes in appetite due to a significant loss in their senses of taste and smell.[32]

In order to prevent the development of pharyngocutaneous fistula, it is common practice to reintroduce oral feeding as of the seventh to tenth day post-surgery, although the ideal timeline remains controversial.[33] Pharyngocutaneous fistula typically develops before the reintroduction of oral feeding, as the pH level and presence of amylase in saliva is more harmful to tissues than other liquids or food. Whether the reintroduction of oral feeding at an earlier post-operative date decreases the risk of fistula remains unclear. However, early oral feeding (within 7 days of the operation) can be conducive to reduced length of hospital stay and earlier discharge from the hospital, entailing a decrease in costs and psychological distress.[34]

Smell and taste rehabilitation

A total laryngectomy causes the separation of the upper air respiratory tract (pharynx, nose, mouth) and lower air respiratory tract (lungs, lower trachea).[35] Breathing is no longer done through the nose (nasal airflow), which causes a loss/decrease of the sense of smell, leading to a decrease in the sense of taste.[35] The Nasal Airflow Inducing Manoeuvre (NAIM), also known as the "Polite Yawning" manoeuvre, was created in 2000 and is widely accepted and used by speech-language pathologists in the Netherlands, while also becoming more widely used in Europe.[36] This technique consists of increasing the space in the oral cavity while keeping the lips closed, simulating a yawn with a closed mouth by lowering the jaw, tongue and floor of the mouth.[36] This causes a negative pressure in the oral cavity, leading to nasal airflow.[37] The NAIM has been recognized as an effective rehabilitation technique to improve the sense of smell.[36]

Quality of life

People with a partial laryngectomy are more likely to have a higher quality of life than individuals with a total laryngectomy.[35] People having undergone total laryngectomy have been found to be more prone to depression and anxiety, and often experience a decrease in the quality of their social life and physical health.[38]

Voice quality, swallowing and reflux are affected in both types, with the sense of smell and taste (hyposnia/anosmia and dysgeusia) also being affected in total laryngectomies (a complaint which is given very little attention by medical professionals).[35][39] Partial or total laryngectomy can lead to swallowing difficulties (known as dysphagia).[1] Dysphagia can have a significant effect on some patients' quality of life following surgery.[1] Dysphagia poses challenges in eating and social involvement, often causing patients to experience increased levels of distress.[1] This effect holds true even after the acute phase of recovery.[1] More than half of patients who received total laryngectomy were found to experience restrictions in their food intake, specifically in what they can eat and how they can eat it.[1] The diet limitations imposed by dysphagia can negatively impact a patient's quality of life, as it can be perceived as a form of participation restriction.[1] Accordingly, these perceived restrictions are more commonly experienced by dysphasic laryngectomy patients compared to non-dysphasic laryngectomy patients.[1] Therefore, it is important to consider dysphagia in short and long-term outcomes post-laryngectomy in order for patients to uphold a higher quality of life.[40] Often, speech-language pathologists are involved in the process of prioritizing swallowing outcomes.[40]

People receiving voice rehabilitation report best voice quality and overall quality of life when using a voice prosthesis as compared to esophageal speech or electrolarynx.[38] Furthermore, individuals going through non-surgical therapy report a higher quality of life than those having undergone a total laryngectomy.[38] Lastly, it is much more difficult for those using alaryngeal speech to vary their pitch,[41] which particularly affects the social functioning of those speaking a tonal language.[41]

References

- Ward, Elizabeth C; Van As-Brooks, Corina J (2014). Head and neck cancer : treatment, rehabilitation, and outcomes (Second ed.). San Diego, CA. ISBN 9781597566599. OCLC 891328651.

- "ACS :: Speech After Laryngectomy". Archived from the original on 2007-11-05. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- Brook I (February 2009). "Neck cancer: a physician's personal experience". Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 135 (2): 118. doi:10.1001/archoto.2008.529. PMID 19221236.

- Gussenbauer, Karl (1874). "Über die erste durch Th. Billroth am ausgeführte Kehlkopf-Extirpation und die Anwendung eines künstlichen Kehlkopfes". Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie. 17: 343–356.

- Stell, P. M. (April 1975). "The first laryngectomy". Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 89 (4): 353–358. doi:10.1017/S0022215100080488. ISSN 0022-2151. PMID 1092780.

- Delavan, D. Bryson (February 1933). "A History of Thyrotomy and Laryngectomy". Laryngoscope. 43 (2): 81–96. doi:10.1288/00005537-193302000-00001. ISSN 0023-852X.

- Donegan, William L. (June 1965). "An early history of total laryngectomy". Surgery. 57 (6): 902–905. ISSN 0039-6060. PMID 14301658.

- Lorenz, K. J. (2015-09-24). "Stimmrehabilitation nach totaler Laryngektomie: Ein chronologischer, medizinhistorischer Überblick". HNO. 63 (10): 663–680. doi:10.1007/s00106-015-0043-4. PMID 26403993.

- Bray, Freddie; Ferlay, Jacques; Soerjomataram, Isabelle; Siegel, Rebecca L.; Torre, Lindsey A.; Jemal, Ahmedin (2018-09-12). "Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. Wiley. 68 (6): 394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492. ISSN 0007-9235. PMID 30207593. S2CID 52188256.

- "Cancer Stat Facts: Larynx Cancer". Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- "What Are the Key Statistics About Laryngeal and Hypopharyngeal Cancers?".

- Maddox, Patrick Tate; Davies, Louise (2012-02-27). "Trends in Total Laryngectomy in the Era of Organ Preservation". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 147 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1177/0194599812438170. PMID 22371344. S2CID 20547192.

- Itzhak., Brook (2013). The laryngectomee guide. ISBN 978-1483926940. OCLC 979534325.

- Orosco, Ryan K.; Weisman, Robert A.; Chang, David C.; Brumund, Kevin T. (2012-11-02). "Total Laryngectomy". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. SAGE Publications. 148 (2): 243–248. doi:10.1177/0194599812466645. ISSN 0194-5998. PMID 23124923. S2CID 20495497.

- Brook, Itzhak (June 2012). "Ventilation of neck breathers undergoing a diagnostic procedure or surgery". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 114 (6): 1318–1322. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824cb923. ISSN 1526-7598. PMID 22451595. S2CID 42926421.

- Hasan, Z.; Dwivedi, R.C.; Gunaratne, D.A.; Virk, S.A.; Palme, C.E.; Riffat, F. (2017-05-27). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of the complications of salvage total laryngectomy". European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO). 43 (1): 42–51. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2016.05.017. PMID 27265037.

- Wulff, N.b.; Kristensen, C.a.; Andersen, E.; Charabi, B.; Sørensen, C.h.; Homøe, P. (2015-12-01). "Risk factors for postoperative complications after total laryngectomy following radiotherapy or chemoradiation: a 10-year retrospective longitudinal study in Eastern Denmark". Clinical Otolaryngology. 40 (6): 662–671. doi:10.1111/coa.12443. ISSN 1749-4486. PMID 25891761. S2CID 25052778.

- Dedivitis, RA; Ribeiro, KCB; Castro, MAF; Nascimento, PC (February 2017). "Pharyngocutaneous fistula following total laryngectomy". Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 27 (1): 2–5. ISSN 0392-100X. PMC 2640019. PMID 17601203.

- Kaye, Rachel; Tang, Christopher G; Sinclair, Catherine F (2017-06-21). "The electrolarynx: voice restoration after total laryngectomy". Medical Devices: Evidence and Research. 10: 133–140. doi:10.2147/mder.s133225. PMC 5484568. PMID 28684925.

- Lorenz, Kai J. (2017). "Rehabilitation after Total Laryngectomy—A Tribute to the Pioneers of Voice Restoration in the Last Two Centuries". Frontiers in Medicine. 4: 81. doi:10.3389/fmed.2017.00081. ISSN 2296-858X. PMC 5483444. PMID 28695120.

- Hopkins, Gross, Knutson, & Candia (2005). "Laryngectomy: an introductory overview". Florida Journal of Communication Disorders. 7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.112.5676.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lewin, Jan S. (2004-01-01). "Advances in Alaryngeal Communication and the Art of Tracheoesophageal Voice Restoration". The ASHA Leader. 9 (1): 6–21. doi:10.1044/leader.FTR1.09012004.6. ISSN 1085-9586.

- Gress, Carla DeLassus (June 2004). "Preoperative evaluation for tracheoesophageal voice restoration". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 37 (3): 519–530. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2003.12.003. ISSN 0030-6665. PMID 15163598.

- Tang, Christopher G.; Sinclair, Catherine F. (August 2015). "Voice Restoration After Total Laryngectomy". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 48 (4): 687–702. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2015.04.013. ISSN 0030-6665. PMID 26093944.

- Brook I (July 2009). "A piece of my mind. Rediscovering my voice". JAMA. 302 (3): 236. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.981. PMID 19602676.

- Brown DH, Hilgers FJ, Irish JC, Balm AJ (July 2003). "Postlaryngectomy voice rehabilitation: state of the art at the millennium". World J Surg. 27 (7): 824–31. doi:10.1007/s00268-003-7107-4. PMID 14509514. S2CID 9515030.

- "Larynx transplant: Q&A". Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- Khemani, S.; Govender, R.; Arora, A.; O'Flynn, P. E.; Vaz, F. M. (December 2009). "Use of botulinum toxin in voice restoration after laryngectomy". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 123 (12): 1308–1313. doi:10.1017/S0022215109990430. ISSN 1748-5460. PMID 19607736.

- Coffey, Margaret; Tolley, Neil (2015). "Swallowing after laryngectomy". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 23 (3): 202–208. doi:10.1097/moo.0000000000000162. PMID 25943964. S2CID 23470240.

- Maclean, Julia; Cotton, Susan; Perry, Alison (2009-06-01). "Post-Laryngectomy: It's Hard to Swallow". Dysphagia. 24 (2): 172–179. doi:10.1007/s00455-008-9189-5. ISSN 0179-051X. PMID 18784911. S2CID 8741206.

- Lips, Marieke; Speyer, Renée; Zumach, Anne; Kross, Kenneth W.; Kremer, Bernd (2015-09-01). "Supracricoid laryngectomy and dysphagia: A systematic literature review". The Laryngoscope. 125 (9): 2143–2156. doi:10.1002/lary.25341. ISSN 1531-4995. PMID 26013745. S2CID 206202759.

- Clarke, P.; Radford, K.; Coffey, M.; Stewart, M. (May 2016). "Speech and swallow rehabilitation in head and neck cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 130 (S2): S176–S180. doi:10.1017/S0022215116000608. ISSN 0022-2151. PMC 4873894. PMID 27841134.

- Aires, Felipe Toyama; Dedivitis, Rogério Aparecido; Petrarolha, Sílvia Miguéis Picado; Bernardo, Wanderley Marques; Cernea, Claudio Roberto; Brandão, Lenine Garcia (October 2015). "Early oral feeding after total laryngectomy: A systematic review". Head & Neck. 37 (10): 1532–1535. doi:10.1002/hed.23755. ISSN 1097-0347. PMID 24816775. S2CID 30024834.

- Talwar, B.; Donnelly, R.; Skelly, R.; Donaldson, M. (May 2016). "Nutritional management in head and neck cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 130 (S2): S32–S40. doi:10.1017/s0022215116000402. ISSN 0022-2151. PMC 4873913. PMID 27841109.

- Sadoughi, Babak (August 2015). "Quality of Life After Conservation Surgery for Laryngeal Cancer". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 48 (4): 655–665. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2015.04.010. ISSN 1557-8259. PMID 26092764.

- van der Molen, Lisette; Kornman, Anne F.; Latenstein, Merel N.; van den Brekel, Michiel W. M.; Hilgers, Frans J. M. (June 2013). "Practice of laryngectomy rehabilitation interventions: a perspective from Europe/the Netherlands" (PDF). Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 21 (3): 230–238. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283610060. ISSN 1531-6998. PMID 23572017. S2CID 215715884.

- Hilgers, Frans J. M.; Dam, Frits S. A. M. van; Keyzers, Saskia; Koster, Marike N.; As, Corina J. van; Muller, Martin J. (2000-06-01). "Rehabilitation of Olfaction After Laryngectomy by Means of a Nasal Airflow-Inducing Maneuver". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 126 (6): 726–32. doi:10.1001/archotol.126.6.726. ISSN 0886-4470. PMID 10864109. S2CID 27808756.

- Wiegand, Susanne (2016-12-15). "Evidence and evidence gaps of laryngeal cancer surgery". GMS Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 15: Doc03. doi:10.3205/cto000130. ISSN 1865-1011. PMC 5169076. PMID 28025603.

- Hinni, Michael L.; Crujido, Lisa R. (2013). "Laryngectomy rehabilitation". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 21 (3): 218–223. doi:10.1097/moo.0b013e3283604001. PMID 23511606. S2CID 38780352.

- Maghami, Ellie; Ho, Allen S. (2018-02-12). Multidisciplinary care of the head and neck cancer patient. Maghami, Ellie,, Ho, Allen S. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 9783319654218. OCLC 1023426481.

- Chan, Jimmy Y. W. (June 2013). "Practice of laryngectomy rehabilitation interventions: a perspective from Hong Kong". Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 21 (3): 205–211. doi:10.1097/MOO.0b013e328360d84e. ISSN 1531-6998. PMID 23572016. S2CID 37522328.