Lesbian characters in fiction

Lesbians are homosexual women.[1][2] The word lesbian is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate nouns with female homosexuality or same-sex attraction.[2][3] This page examines lesbian characters in fictional works as a whole, focusing on characters and tropes in cinema and fantasy.

For more information about fictional characters in other parts of the LGBTQ community, see the corresponding pages about asexual, pansexual, and non-binary, intersex, and gay characters in fiction.

Lesbian characters and tropes

Lesbian characters are portrayed in the media, especially when it comes to marriage, parenting, feminism, and romantic relationships. Some have stated that this leads to exploitative and unjustified plot devices, such as tropes involving butch or femme lesbians and lesbian parents. In the media, lesbian marriage and parenting are depicted in shows such as the live-action television show The Fosters and the animated series Steven Universe.

During the twentieth century, lesbians such as Gertrude Stein and Barbara Hammer were noted in the U.S. avant-garde art movements, along with figures such as Leontine Sagan in German pre-war cinema. Since the 1890s the underground classic The Songs of Bilitis has been influential on lesbian culture. This book provided a name for the first campaigning and cultural organization in the United States, the Daughters of Bilitis. During the 1950s and 1960s, lesbian pulp fiction was published in the U.S. and the United Kingdom, often under "coded" titles such as Odd Girl Out, The Evil Friendship by Vin Packer and The Beebo Brinker Chronicles by Ann Bannon. British school stories also provided a haven for "coded" and sometimes outright lesbian fiction. During the 1970s the second wave of feminist-era lesbian novels became more politically oriented. Works often carried the explicit ideological messages of separatist feminism and the trend carried over to other lesbian arts. Rita Mae Brown's debut novel Rubyfruit Jungle was a milestone of this period; Patience and Sarah, by Isabel Miller, became a cult favorite. The opera, based on the novel has been described as the first lesbian opera.[4] Molly Bolt in the 1973 novel, Rubyfruit Jungle, has numerous romantic and sexual relationships with other women,[5] and she confronts the "hypocrisies of both heterosexual and homosexual societies."[6] By the early 1990s, lesbian culture was being influenced by a younger generation who had not taken part in the "Feminist Sex Wars" and this strongly informed post-feminist queer theory along with the new queer culture. Apart from this, the first lesbian-themed feature film was Mädchen in Uniform (1931), based on a novel by Christa Winsloe and directed by Leontine Sagan, tracing the story of a schoolgirl called Manuela von Meinhardis and her passionate love for a teacher, Fräulein von Bernburg. It was written and mostly directed by women. The impact of the film in Germany's lesbian clubs was overshadowed, however, by the cult following for The Blue Angel (1930). Until the early 1990s, any notion of lesbian love in a film almost always required audiences to infer the relationships.

Lesbian characters have made very rare appearances in scripted radio programs, almost always as killers or murder victims. Homosexuality was not discussed on television until the mid-1950s. Even so, many science fiction series have featured lesbian characters. Later, mainstream American broadcast media have created a subgenre of lesbian portrayal in what is sometimes referred to as the "lesbian kiss episode", in which a lesbian or bisexual female character and a heterosexual-identified character kiss. In most instances, the potential of a relationship between the women does not survive past the episode and the lesbian character rarely appears again. For years, there have been many LGBT couples in anime, with various characters who people feel validate their sexuality and gender, even if these characters are not canon.[7] This is because LGBTQ anime is not new,[8] although some reviewers say that there is a "wealth of LGBTQ+ focused series" within anime, especially those with earnest stories.[9] Others noted the importance of having "yourself represented in one of the world's most popular entertainment."[10] In recent years, lesbian characters have gained relative prominence in various formats, especially since 2013 with the advent of streaming platforms like Netflix[11] and Hulu.[12]

LGBT themes and characters were historically omitted intentionally from the content of comic strips and comic books, due to either censorship, the perception that LGBT representation was inappropriate for children, or the perception that comics as a medium were for children. In the 1950s, American comic books, under the Comics Code Authority, adopted the Comic Code which, under the guise of preventing "perversion", largely prevented the presentation of LGBT characters for a number of decades.[13] Within the Japanese anime and manga, yaoi is the tradition of representing same-sex male relationships in materials that are generally created by women artists and marketed mostly for Japanese girls [14] while the genre known as yuri focuses on relationships between women. In recent years, the number of LGBT characters in mainstream comics has increased greatly. There exist a large amount of openly gay and lesbian comic creators that self-publish their work on the internet. These include amateur works, as well as more "mainstream" works, such as Kyle's Bed & Breakfast.[15] According to Andrew Wheeler from Comics Alliance, webcomics "provide a platform to so many queer voices that might otherwise go undiscovered."[16]

Prominent examples

There have been many prominent lesbian characters in animated series, film, graphic novels, and other media. In anime, Juri Arisugawa, who is explicitly in love with her female classmate, Shiori, in both the TV series and movie, is described as "homosexual" by the creators of the 1997 series Revolutionary Girl Utena in the DVD booklet.[17] Also in the 1990s, the series Sailor Moon featured two characters (Haruka Tenoh / Sailor Uranus and Michiru Kaioh / Sailor Neptune) in a romantic relationship with each other, even though in the original release of the English version of the anime, where they were made "cousins".[18][19] In later years, Futaba Aasu in Puni Puni Poemy[20] along with Fumi Manjōme and Akira Okudaira in Sweet Blue Flowers[21][22] were openly lesbian characters. Apart from these characters, the main protagonists of Yurikuma Arashi[lower-alpha 1] are presented as having various sexual encounters and romantic relationships.[23][24] There were numerous characters in Western animation and in other media which stood apart from others. For Western animation, this includes Patty Bouvier in The Simpsons,[25][26] Pearl in Steven Universe,[27][28] and Ruby and Sapphire in Steven Universe who have a romantic relationship with each other, and stay permanently fused to form Garnet.[29][30][31] One series, She-Ra and the Princesses of Power featured various lesbian characters, such as, Netossa, Spinnerella, Adora, and Catra,[32][33] the latter two around whom the story revolves.[34][35] More recently, Amity Blight in the series The Owl House has been described as a lesbian, since she has a crush on her classmate, Luz Noceda.[36][37][38]

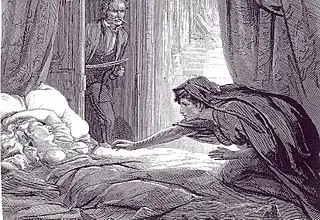

While anime and Western animation have lesbian characters, so do live-action television series and those in other media. In 1929, Countess Geschwitz in Pandora's Box would become cinema's first explicit lesbian character.[39] Years later, in 1989, the relationship between Lorraine and Theresa "Tee" in the series The Women of Brewster Place became the first black lesbian relationship portrayed on American television.[40][41] Additionally, Ellen in the series, Ellen came out in 1997 as lesbian, becoming one of "TV’s first openly gay main characters," seen with a female lover named Laurie, in the show's final season before the show was cancelled.[42] In graphic novels, Batwoman / Kate Kane became the highest profile lesbian in the DC Universe, after appearing in the comic series | 52 from 2006-2007.[43][44] In literature, Carmilla, published as part of the book, In a Glass Darkly, in 1872, is considered the first lesbian vampire story.[45][46] Years later, in 1966, Renee LaRoche became the first "openly out Indigenous lesbian" in the detective novel Along the Journey River.[47] and Happy Endings Are All Alike became the first novel with a "clearly lesbian main character," named Jaret Taylor who comes out in the book's first line.[48] In 2015, Moff Delian Mors became the first LGBT character in the Star Wars canon,[lower-alpha 2] with her sexuality is not a major concern in the novel, suggesting that "homophobia isn't an issue in the Empire," and something the Imperial Army doesn't worry about, even as they fight rebels.[49][50] On a similar note, the party member Juhani in Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, a video game, is lesbian, though bugged coding on the initial release allowed her to be attracted to the player character regardless of gender. In subsequent patches, she reverts to same-sex preferences, with her and another female Jedi were also heavily implied to be lovers, making Juhani the first known gay character in the Star Wars universe.[51]

Notes

- Kureha Tsubaki, Sumika Izumino, Ginko Yurishiro, Lulu Yurigasaki, and Yurika Hakonaka

- There were same gender relationships in Star Wars: The Old Republic online roleplaying game after an outcry, introduced in 2015.

See also

References

- "Lesbian". Oxford Reference. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- Zimmerman, p. 453.

- Committee on Lesbian Health Research Priorities; Neuroscience and Behavioral Health Program; Health Sciences Policy Program, Health - Sciences Section - Institute of Medicine (1999). Lesbian Health: Current Assessment and Directions for the Future. National Academies Press. p. 22. ISBN 0309174066. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- Hilferty, Robert (June 1, 1998). "Women in love". Opera News.

- Day, Frances Ann (2000). Lesbian and Gay Voices: An Annotated Bibliography and Guide to Literature. Greenwood Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-313-31162-8.

- Kantrowitz, Arnie. "Humor: Use of a Surrogate and Connecting Openly Gay and Lesbian Characters to a Larger Society". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- Casalena, Em (October 8, 2016). "The 15 Coolest LGBT Relationships In Anime". ScreenRant. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- B, Zuleika (June 18, 2018). "9 Must-See LGBTQ Anime". Fandom. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Manente, Kristina (September 25, 2018). "10 LGBTQ+ anime that you need to watch now". Syfy. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Valens, Ana (May 19, 2020). "10 LGBTQ+ Anime Characters We Love". Pride.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Benard, Riese (December 30, 2019). "The Best TV Shows Of 2019 With LGBT Women Characters". Autostraddle. The Excitant Group LLC. Archived from the original on January 20, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- The TV Team (March 17, 2020). "43 Hulu Streaming TV Shows With Lesbian and Bisexual Women Characters". Autostraddle. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Booker, M. Keith (May 11, 2010). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels [2 volumes]: [Two Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 246–. ISBN 9780313357473. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Publishing, Here (October 14, 2003). The Advocate. Here Publishing. pp. 86–. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Palmer, Joe (October 16, 2006). "Gay Comics 101". AfterElton.com. p. 3. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007.

- Wheeler, Andrew (June 29, 2012). "Comics Pride: 50 Comics and Characters That Resonate with LGBT Readers". Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014.

- Revolutionary Girl Utena: Student Council Saga Limited Edition Set (Booklet interview with Chiho Saito). Nozomi Entertainment. 2011.

- Roncero-Menendez, Sara (May 21, 2014). "Sailor Neptune and Uranus Come Out of the Fictional Closet". Huff Post. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Peters, Megan (October 7, 2018). "Did You Know 'Sailor Moon' Had To Censor Its Lesbian Lovers?". comicbook.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2019. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

- Christi (2001). "Puni Puni Poemy [review]". T.H.E.M. Anime Reviews. Archived from the original on July 25, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Meek, Bradley (2009). "Sweet Blue Flowers [review]". T.H.E.M. Anime Reviews. Archived from the original on July 25, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Loo, Egan (March 6, 2009). "Takako Shimura's Aoi Hana Yuri Manga Gets TV Anime". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on March 26, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Ekens, Gabriella (January 27, 2015). "Yurikuma Arashi - Episode 4 [Review]". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on April 3, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

This leads us to where the show is now – with Kureha, Ginko, and Lulu all together, but separate, pining after different people...It's becoming more apparent that Kureha is probably Ginko's “special person,” and while Lulu seems to have accepted her perceived role as Ginko's second fiddle

- Ekens, Gabriella (April 1, 2015). "Yurikuma Arashi - Episode 12 [Review]". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Elledge, Jim (2010). Queers in American Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 255–. ISBN 9780313354571. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Perkins, Dennis (March 26, 2020). "A well-written Simpsons gives the family a satisfying vacation for a change". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- "Steven Universe: "We Need To Talk"". The A.V. Club. 18 June 2015. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- "It's a Wonderful Jimmy Aquino — Comic News Insider Episode 679 – MoCCA Mirth w/..." It's a Wonderful Jimmy Aquino. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Johnston, Joe (March 13, 2015). "are you allowed to tell us if Sapphire and Ruby's love is romantic or more platonic?". Archived from the original on March 15, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Jones-Quartey, Ian [@ianjq] (July 19, 2015). "@xavfucker by human standards & terminology that would be a fair assessment!" (Tweet). Archived from the original on April 4, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020 – via Twitter.

- Hogan, Heather (August 9, 2018). ""Steven Universe" Makes History, Mends Hearts in a Perfect Lesbian Wedding Episode". Autostraddle. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Matadeen, Renaldo (November 15, 2018). "Netflix's She-Ra and the Princesses of Power Delivers on Its LGBTQ Promise". CBR. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Stevenson, Noelle (November 2019). "AMA with She-Ra showrunner Noelle Stevenson and Double Trouble's voice Jacob Tobia TODAY! Come in and drop off your questions, to be answered soon!". Reddit. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Knight, Rosie (May 15, 2020). "Noelle Stevenson on the Legacy of SHE-RA". Nerdist News. Nerdist Industries. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Stevenson, Noelle [@Gingerhazing] (May 20, 2020). "It was something the crew and I discussed/worked together on. The good thing was that we had a framework, and knew that Catra and Adora would reconcile in the last season, so we kept building towards that until it made sense to reveal the romantic aspect and get everyone onboard" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020 – via Twitter. She was responding to the question by a fan: "how was the process to write and show scenes that pointed out catradora without actually saying it in previous seasons, so would make sense for the last part of the show? was there any moment that you wish you were able to show?"

- Adams, Tim (August 9, 2020). "The Owl House: Disney Animated Series' LGBTQ+ Relationship is No Longer Subtext". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

Luz and Amity began as rivals, but The Owl House has slowly built up a friendship between the two girls. Once Luz learned that they share many of the same interests, she has tried to befriend Amity. Since then, their relationship has continued to grow, with more clues being dropped that feelings could be brewing. While fans are aware of Amity's feelings for Luz, they will have to wait and see if and when Luz makes her feelings known as well.

- Terrace, Dana (September 2, 2020). "Amity is intended to be a lesbian and Luz is bi. I apologize for my original post which was worded vaguely. Romantic threads are fun and I love how many people are connecting to that storyline but my personal taste as a storyteller will never allow me to write a full on romance saga. THAT BEING SAID... Me and the crew are having a crap ton of fun developing this thread in season 2. All the ins and outs of these storylines we're keeping track of... Feels like we're knitting". Reddit. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Terrace, Dana (September 2, 2020). "I definitely think Luz is her first crush (or at least her first big crush). That's why it's so overwhelming haha". Reddit. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Rikfind, Candida (2002). "Screening Modernity: Cinema and Sexuality in Ann-Marie MacDonald's Fall On Your Knees". journals.lib.unb.ca..

- Loon, Malinda (May 5, 2005). "Back in the Day: "The Women of Brewster Place"". AfterEllen. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Searles, Jourdain (February 25, 2019). "How 'The Women of Brewster Place' Revolutionized the Depiction of Black Women on TV". Thrillist. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Mitchell, Bea (July 18, 2017). "The 12 best ever lesbian characters on TV". PinkNews. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Robinson, Bryan (June 14, 2006). "Holy Lipstick Lesbian! Meet the New Batwoman". ABC News. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Booker, M. Keith (October 30, 2014). Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1512–. ISBN 9780313397516. Retrieved January 2, 2015.

- Garber, Eric; Paleo, Lyn (1983). "Carmilla". Uranian Worlds: A Guide to Alternative Sexuality in Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror. G. K. Hall. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8161-1832-8.

- LeFanu, J[oseph] Sheridan (1993). "Carmilla". In Keesey, Pam (ed.). Daughters of Darkness: Lesbian Vampire Stories. Pittsburgh, PA: Cleis Press.

- Nina, Knight (2019). "Along the Journey River and Evil Dead Center". Tribal College. 30 (3). Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Lo, Malinda (May 22, 2007). "13 Lesbian and Bi Characters You Should Know (page 1)". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- Keane, Sean (April 28, 2015). "REVIEW: Star Wars: Lords of the Sith throws Darth Vader and the Emperor onto the battlefield". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- Hensley, Nicole (March 11, 2015). "Star Wars novelist adds first lesbian character to canon". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- MacDonald, Keza. "A Gay History of Gaming". IGN. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved December 23, 2020.