List of unsolved murders (before the 20th century)

This list of unsolved murders includes notable cases where victims have been murdered under unknown circumstances.

Before the 19th century

- Ötzi, also called the Iceman, is the well-preserved natural mummy of a man who lived between 3400 and 3100 BCE.[1] The mummy was found in September 1991 in the Ötztal Alps. The cause of death remained uncertain until 10 years after the discovery of the body.[2] It was initially believed that Ötzi died from exposure during a winter storm. Later it was speculated that Ötzi might have been a victim of a ritual sacrifice, perhaps for being a chieftain.[3][4] This explanation was inspired by theories previously advanced for the first millennium BCE bodies recovered from peat bogs such as the Tollund Man and the Lindow Man.[4] In 2001, X-rays and a CT scan revealed that Ötzi had an arrowhead lodged in his left shoulder when he died[5] and a matching small tear on his coat.[6] The discovery of the arrowhead prompted researchers to theorize Ötzi died of blood loss from the wound, which would probably have been fatal even if modern medical techniques had been available.[7] Further research found that the arrow's shaft had been removed before death, and close examination of the body found bruises and cuts to the hands, wrists and chest, and cerebral trauma indicative of a blow to the head. One of the cuts was to the base of his thumb that reached down to the bone but had no time to heal before his death. Currently, it is believed that Ötzi bled to death after the arrow shattered the scapula and damaged nerves and blood vessels before lodging near the lung.[8]

- The Cashel Man (20–25), is a bog body of a murder victim found on 10 August 2011 near Cashel in County Laois, Ireland.[9] The man had lived around 2000 BC.

- The Borremose bodies are three bog bodies separately discovered in the Borremose peat bog in Himmerland, Denmark, between 1946 and 1948. The bodies—one male, two female—are estimated to have been undiscovered since c. 770 and 400 BCE respectively.[10][11]

- The Kayhausen Boy is a mummy and male murder victim and was naturally preserved in a sphagnum bog in Lower Saxony. This decedent was discovered in 1922.[12] He had died between 300 and 400 BCE.[13] and whoever killed him is unknown.

- The Weerdinge Men were two bog bodies who were naked who were found in the southern part of Bourtanger Moor in 1904 Drenthe in the Netherlands. One of them was a murder victim[14] and most likely died between 160 BC and 220 AD.

- The Osterby Man, also known as "The Osterby Head" is a bog body of a murder victim that was found with only the skull and hair surviving. It was discovered by peat cutters to the southeast of Osterby, Germany. The hair is tied in a Suebian knot. The head is at the State Archaeological Museum at Gottorf Castle in Schleswig, Schleswig-Holstein. The head was discovered on 26 May 1948, by Otto and Max Müller of Osterby, who were cutting peat on their father's land.[15] The skull of the body of Dätgen Man, who also had a Suebian knot, was found several metres from his head.[16] He is said to have been killed in the Late Iron Age or the Roman period, mostly likely between 75 and 130 CE.[17][18] and the murder remains unsolved.

- The Huldremose Woman also known as the "Huldre Fen Woman" is a bog body of a female murder victim who had lived during the Iron Age, around 160 BCE to 340 CE.[19] It was found in 1879 from a peat bog that was close to Ramten, Jutland, Denmark.

- The Elling Woman is a bog body of a female murder victim[20] found in 1938 west of Silkeborg, Denmark who most likely died during 280 BCE in the Nordic Iron Age.

- The Haraldskær Woman also known as the "Haraldskjaer Woman" are the remains of a woman whose complete skeleton was found intact in a body bag in a bog in Jutland, Denmark and it was also naturally preserved as well. She is dated to have lived from around 490 BCE (pre-Roman Iron Age).[21] She is said to have been murdered during the 5th century BCE.[22]

- The Clonycavan Man is bog body of a murder victim[23] discovered in Clonycavan, Ballivor, County Meath, Ireland in March 2003. He is said to have lived during the Iron Age and died between 392 BC and 201 BC.[24]

- The Tollund Man is a mummy of a male murder victim found in 1950 on the Jutland peninsula, in the country of Denmark.[25] and was naturally preserved as a bog body. He had lived during the 4th century BC, which was during the Pre-Roman Iron Age,[26][25] and was murdered by persons unknown.

- The Grauballe Man is a bog body that was found in 1952 that was close to the village of Grauballe in Jutland, Denmark in a peat bog of a male murder victim that dated to the late 3rd century BC,[27] during the early Germanic Iron Age.

- Caesarion (17), (Ptolemy XV Philopator Philometor Caesar), 30 BC; the son of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar, and as such the last king of the Ptolemaic dynasty of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, ruling alone for eleven days, whose death at the orders of Augustus (while still Octavian) is accepted in 30 BC,[28] and yet the exact circumstances of his death and the location of his body are not documented.[28]

- The Yde Girl (16), are the remains of a girl found on 12 May 1897 in a bog body in the Stijfveen a peat bog that is near by the village of Yde, Netherlands.[29] She had lived around 54 BC and 128 AD and her bones showed signs of damage[30]

- The Emperor Valentinian II, 15 May 392; he was found hanged in his residence in Vienne in Gaul. Frankish General Arbogast claimed it was suicide, although some sources suggest that, having been dismissed by the emperor, the general had murdered him.[31]

- Dagobert II, 679; he was one of the last Merovingian kings, murdered in the Ardennes Forest on 23 December.[32] Whoever killed him is unknown.

- Emperor Taizu of Song (49), the first emperor of Song Dynasty, died in 976.[33] There is no records about how he died. However, his younger brother got throne succession under the circumstance of he had two grown sons. There is a folk story “shadows by the candle and sounds from an axe” that shows he was murdered by his brother.

- Wenceslaus III of Bohemia, the last Přemyslid King of Bohemia died on 4 August 1306 at just short of 17 years of age in Olomouc. It is known he was murdered and most chronicles report the murderer was a Thuringian mercenary named Conrad von Bottennstein, but this has been rejected as later blaming since the real Conrad died around 1320 and the chronicles also report the supposed murder was stabbed to death by guards moments after the murder. The person who ordered the murder is completely unknown, but most assumed it was either Albert I of Germany or Wladyslaw I of Poland, who both had political animosity towards him and against the latter of whom Wenceslaus was then marching with an army since both claimed the Kingdom of Poland as theirs.

The Bocksten Man, discovered in 1936. He had likely been murdered in the 14th century

- The Bocksten Man is an individual whose body was discovered in Varberg Municipality, Sweden, in 1936. The individual had been impaled to the bottom of a lake with two wooden poles. The clothing worn by this individual most likely dates his murder to sometime in the 14th century. The remains are on display at the Varberg County Museum.[34]

- Momia Juanita, also known as the Inca Ice Maiden and Lady of Ampato, is the well-preserved frozen body of an Inca girl, who was murdered as an offering to the Inca gods, sometime between 1450 and 1480 when she was about 12–15 years old, by persons unknown.[35] She was discovered on Mount Ampato (part of the Andes cordillera) in southern Peru in September 1995 by anthropologist Johan Reinhard and his Peruvian climbing partner, Miguel Zárate.

- The Holy Child of La Guardia is a Spanish Roman Catholic folk saint and the subject of a medieval blood libel in the town of La Guardia which is located in the central Spanish province of Toledo (Castile–La Mancha).[36][37] An auto-da-fé was held outside of Ávila in 16 November 1491 that ended in the public execution of several Jews and conversos. The suspects "had confessed" under torture to murdering a child. People who were executed were Benito Garcia, the converso who had initially confessed to the child's murder. However since no body was ever found and there is no defenite proof that a child disappeared or was killed. Because of contradictory confessions, the court had trouble coherently depicting how events possibly took place.[38] The true identity of the child is unknown as well.

- Giovanni Borgia, 2nd Duke of Gandía, 1497; his body was recovered in the Tiber with his throat slit and about nine stab wounds on his torso.[39] His father, Pope Alexander VI, launched an investigation only for it to end abruptly a week later. Theories range from the Orsini family to his own brothers, Cesare Borgia and Gioffre Borgia, having committed the crime.

- Moctezuma II, 1520, Aztec emperor; according to Spanish accounts he was killed by his own people; according to Aztec accounts he was assassinated by the Spanish.[40]

- Robert Pakington (46–47), 1536, likely to have been the first person murdered with a handgun in London.[41]

- Plomo Mummy (also known as Boy of El Plomo, El Plomo Mumm, or La Momia del Cerro El Plomo in Spanish) is the well preserved remains of an Incan child who is said to have lived about 500 years ago, discovered on Cerro El Plomo near Santiago, Chile in 1954.[42][43]

- Expatriate English Royalists are believed to have ambushed and murdered Isaac Dorislaus in 1649,[44][45] then a diplomat representing the interests of the Commonwealth to the Dutch government at The Hague, in retaliation for his role in the trial and execution of Charles I. No suspects were ever identified, although some Royalists later boasted of having taken part.

- Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey (56), in 1678; he was found impaled on his own sword and strangled at Primrose Hill, London.[46] Three men were hanged, but later the witness' statement was found to be perjured.

- Charles XII of Sweden (36), was killed by bullet in siege trench in Fredrikshald, Norway while observing enemy on 30 November 1718[47] after it had entered the side of head leading to the speculation that he was shot by one of his own men.

- Alessandro Stradella (38), 1682, composer; he was stabbed to death at the Piazza Banchi of Genoa. His infidelities were well known, and many theorize that a nobleman of the Lomellini family hired the killer.[48]

- Jean-Marie Leclair (67), 1764, violinist and composer; he was found stabbed in his Paris home. Although the murder remains a mystery, his nephew, Guillaume-François Vial, and Leclair's ex-wife were considered main suspects at the time.[49]

- Although the colonial authorities in Pennsylvania at the time investigated the two December 1764 Paxton Boys massacres of defenseless Conestoga communities near present-day Millersville[50] as a criminal mass murder, the perpetrator were never identified.

19th century

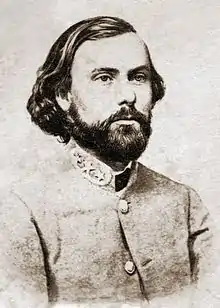

Thomas Hindman, American politician and murder victim

- Elijah Parish Lovejoy (34), was an American Presbyterian minister, journalist, newspaper editor, and abolitionist. He was shot and killed on 7 November 1837[51] by a pro-slavery mob in Alton, Illinois, during their attack on the warehouse of Benjamin Godfrey and W. S. Gillman to destroy Lovejoy's press and abolitionist materials.

- Mary Rogers (21–22), also known as the "Beautiful Cigar Girl"; her body was found in the Hudson River on 28 July 1841. The story became a national sensation and inspired Edgar Allan Poe to write "The Mystery of Marie Rogêt" (1842).[52]

- Helen Jewett (22), American prostitute who was murdered in New York City on 10 April 1836.[53] Whoever killed her is unknown.

- Françoise de Choiseul-Praslin, wife of French duke Charles de Choiseul-Praslin; she died shortly after a beating and stabbing in the family's Paris apartment on 17 August 1847.[54] Her husband was arrested, but committed suicide during trial, protesting his innocence all along. No other suspect has ever been identified. The scandal caused by the case helped to provoke the French Revolution of 1848.

- Sakamoto Ryōma (31), was a Japanese samurai and a prominent figure in the movement to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate who was assassinated at the Ōmiya Inn in Kyoto, not long before the Meiji Restoration took place. On the night of 10 December 1867, assassins gathered at the door of the inn and one approached and knocked, acting as an ordinary caller. The door was answered by Ryōma's bodyguard and manservant, a former sumo wrestler who told the stranger he would see if Ryōma was accepting callers at that hour of the evening. When the bodyguard turned his back, the visitor at the door drew his sword and slashed his back, which became a fatal wound.[55]

- Nakaoka Shintarō (29), a samurai in Bakumatsu period Japan, and a close associate of Sakamoto Ryōma in the movement to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate.[56] was killed on 12 December 1867. [57]

- Thomas C. Hindman (40), an American politician assassinated by one or more assailants on 27 September 1868. The assassins fired through his parlor window while he was reading his newspaper with his children in Helena, Arkansas, United States.[58]

- Alexander Boyd was the county solicitor of Greene County, Alabama, who was lynched by the Ku Klux Klan on 31 March 1870.[59]

- Benjamin Nathan (56), a financier turned philanthropist; was found beaten to death in his New York City home on 28 July 1870. Several suspects were identified, including Nathan's profligate son Washington, who discovered the body along with his brother, but none were ever indicted.[60]

- Juan Prim (56), a Spanish general and statesman; in December 1870, he was shot through the windows of his carriage by several assailants and died two days later.[61] In 2012, his body was exhumed; the autopsy showed he may have been strangled on his deathbed, but results were deemed inconclusive.

- Sharon Tyndale (65), former Illinois Secretary of State, was robbed and shot as he walked from his house in Springfield to the nearby train station early on the morning of 29 April 1871.[62]

- Henry Weston Smith (49), a minister, was found dead on the road between his home in Crook City, South Dakota, and Deadwood, where he was going to give a sermon, on 20 August 1876.[63] Smith was not robbed and the motive for his death remains unknown

- George Colvocoresses (55), Greek American naval commander and explorer, died of a gunshot wound while returning to a ferryboat on 3 June 1872, in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The insurance company claimed it was suicide, but eventually settled with his family.[64]

- Arthur St. Clair, an African-American community leader in Brooksville, Florida, was killed by a white mob in 1877[65] after presiding over an interracial marriage. The papers relating to the case were incinerated when the county courthouse was destroyed in an arson attack, preventing the killers from being found.

- Martin DeFoor (73), an early settler of Atlanta, Georgia, was along with his wife the victim of an axe murder on their farm on 25 July 1879.[66]

- Two trials in Canada's Black Donnellys massacre, in which five members of a family of Irish immigrants were found murdered in the ashes of their Ontario farm after an angry mob attacked it on 4 February 1880,[67] allegedly as a result of feuds with their neighbors, resulted in all the suspects being acquitted.

- John Henry Blake (74), agent for one of Ireland's more despised British landlords, was shot and killed along with his driver on their way to Mass outside Loughrea on 29 June 1882.[68] The case received considerable attention at the time because Blake's boss, Hubert de Burgh-Canning, 2nd Marquess of Clanricarde, was a nobleman. Although his wife survived the attack, she was unable to identify any suspects.

- The Rahway murder of 1887 also known as Unknown Woman and Rahway Jane Doe is the murder of an unidentified young woman whose body was found in Rahway, New Jersey on 25 March 1887. Four brothers traveling to work at the felt mills by Bloodgood's Pond in Clark, New Jersey early one morning found the young woman lying off Central Avenue near Jefferson Avenue several hundred feet from the Central Avenue Bridge over the Rahway River.[69] Her body was very bloody and had been subjected to a beating.[70]

- The Whitehall Mystery In 1888, the dismembered remains of a woman were discovered at three different sites in the centre of London, including the future site of Scotland Yard.[71]

- John M. Clayton (48), American politician, was shot on the evening of 29 January 1889 in Plumerville, Arkansas, after starting an investigation into possible election fraud. [72]

- Belle Starr (40) was a notorious female American outlaw.[73] On 3 February 1889, two days before her 41st birthday, she was killed. She was riding home from a neighbor's house in Eufaula, Oklahoma when she was ambushed. Her death resulted from shotgun wounds to the back, neck, shoulder, and face.[74]

- Andrew Jackson Borden and Abby Durfee Borden, father and stepmother of Lizzie Borden, both killed in their family house in Fall River, Massachusetts on the morning of 4 August 1892, by blows from a hatchet. In the case of Andrew Borden, the hatchet blows not only crushed his skull, but cleanly split his left eyeball. Lizzie was later arrested and charged for the murders. At the time her stepmother was killed, Lizzie was the only other person known to have been in the house. Lizzie and the maid, Bridget Sullivan, were the only other people known to have been in the house at the time Mr. Borden was killed. Lizzie was acquitted by a jury in the following year of 1893.[75]

- Frazier B. Baker and Julia Baker were a father and daughter who were murdered on 22 February 1898 in their own house in Lake City, South Carolina.[76]

- The Gatton murders occurred 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the rural Australian town of Gatton, Queensland, on 26 December 1898. Siblings Michael, Norah and Ellen Murphy were found deceased the morning after they left home to attend a dance in the town hall which had been cancelled. The bodies were arranged with the feet pointing west and both women had their hands tied with handkerchiefs. This signature aspect has never been repeated in Australian crime and to date remains a mystery.[77]

- William Goebel (44), an American politician who was shot and mortally wounded on the morning of 30 January 1900 in Frankfort, Kentucky, one day before being sworn in as Governor of Kentucky. The next day the dying Goebel was sworn in and, despite the best efforts of eighteen physicians attending him, died on the afternoon of 3 February 1900. Goebel remains the only state governor in the United States to die by assassination while in office.[78]

References

- Bonani, Georges; Ivy, Susan D.; et al. (1994). "AMS 14

C

Age Determination of Tissue, Bone and Grass Samples from the Ötzal Ice Man" (PDF). Radiocarbon. 36 (2): 247–250. doi:10.1017/s0033822200040534. Retrieved 4 February 2016. - "Who Killed the Iceman? Clues Emerge in a Very Cold Case". The New York Times. 26 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Sarah Ives (30 October 2003), Was ancient alpine "Iceman" killed in battle?, National Geographic News, archived from the original on 15 October 2007, retrieved 25 October 2007

- Franco Rollo [], et al. (2002), "Ötzi's last meals: DNA analysis of the intestinal content of the Neolithic glacier mummy from the Alps", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99 (20): 12594–12599, doi:10.1073/pnas.192184599, PMC 130505, PMID 12244211

- Stephanie Pain (26 July 2001), Arrow points to foul play in ancient iceman's death, NewScientistTech, archived from the original on 23 August 2014

- James M. Deem (3 January 2008), Ötzi: Iceman of the Alps: Scientific studies, archived from the original on 2 September 2015, retrieved 6 January 2008

- Alok Jha (7 June 2007), "Iceman bled to death, scientists say", The Guardian, archived from the original on 13 March 2016

- Rory Carroll (21 March 2002). "How Oetzi the Iceman was stabbed in the back and lost his fight for life". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007.

- "Kingship and Sacrifice Exhibition National Museum of Ireland". National Museum of Ireland.

- Coles, B. & Coles, J., People of the wetlands. Bogs, bodies and lake-dwellers. Guild publishing. London, 1989

- Andersen, S., Geertinger, P., "Bog bodies investigated in the light of forensic medicine." Journal of Danish archaeology Vol. 3 1984, s. 111-119

- "The Bog Bodies - Why do so many show signs of violent death?". Survival Update. 2020-11-13. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Archaeology.about.com. Archaeology.about.com (4 August 2010). Retrieved on 15 September 2011.

- NOVA | The Perfect Corpse | Bog Bodies of the Iron Age | PBS

- Karl Kersten, "Ein Moorleichenfund von Osterby bei Eckernförde", Offa. Berichte und Mitteilungen zur Urgeschichte, Frühgeschichte und Mittelalterarchäologie 8 (1949) 1–2, p. 1, Fig. 1 (in German)

- Strom, Caleb. "Osterby Man Still Has a Great Hairdo Nearly 2,000 Years On!". ancient-origins.net. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- Van der Sanden, Through Nature to Eternity, p. 81.

- Johannes van der Plicht, Wijnand van der Sanden, A. T. Aerts and H. J. Streurman, "Dating bog bodies by means of 14C-AMS" Archived 2011-09-17 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Archaeological Science 31.4, 2004, pp. 471–91, p. 480.

- Gleba, Margarita; Mannering, Ulla (2010) "A thread to the past: the Huldremose Woman revisited". Archaeological textiles newsletter. Leiden (50): 32–37. ISSN 0169-7331.

- Silkeborg Museum (2004). "Elling Woman". Denmark. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Ebbesen, Klaus (1986). Døden i mosen (in Danish). Copenhagen: Carlsen’s Forlag. p. 7. ISBN 978-87-562-3369-9. OCLC 18616344.

- Archaeological Institute "Haraldskaer Woman: Bodies of the Bogs", Archaeology, Archaeological Institute of America, December 10, 1997.

- Sanz, Catherine (19 February 2019). "Google offended by the naked truth". The Times. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- "Iron Age 'Bog Man' Used Imported Hair Gel". National Geographic. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Glob, P. (2004). The Bog People: Iron-Age Man Preserved. New York: New York Review of Books. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-59017-090-8.

- Susan K. Lewis—PBS (2006). "Tollund Man". Public Broadcasting System—NOVA. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- Asingh., Pauline; Lynnerup, Niels (2007). Grauballe man: An Iron Age bog body revisited. Aarhus: Aarhus University press. p. 17. ISBN 978-87-88415-29-2.

- "Caesarion". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Deem, James M. "Drents Museum in Assen, the Netherlands: The Yde Girl". Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "Featured Netherlands Mummy Museums: Drents Museum in Assen: The Yde Girl". web.archive.org. 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- History Today magazine; Volume 69; May 2019; Issue 5; Page 27

- "The Priory of Sion". skirret.com. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Song Shi, ch. 3.

- Lindh, Nic. "Murdered 600 years ago". Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- dhwty. "Mummy Juanita: The Sacrifice of the Inca Ice Maiden". ancient-origins.net. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- La Guardian, Holy Child of, Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- Robert Michael, A History of Catholic Antisemitism: The Dark Side of the Church (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), p. 70.

- Smelik, Klaas: "Herleefde Tijd: Een Joodse Geschiedenis", page 198. Acco, 2004. ISBN 90-334-5508-0

- "Giovanni (Juan) Borgia – Prisoners of Eternity". Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Tototepec (23 July 2018). "The Death of Emperor Montezuma". The Aztec Vault. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Betham, rev William (1801). The baronetage of England, or, The history of the English baronets, and such baronets of Scotland, as are of English families.

- Horne, P. D.; Kawasaki, S. Q. (1984). "The Prince of El Plomo: A paleopathological study". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 60 (9): 925–31. PMC 1911799. PMID 6391593.

- "Ice Mummies of the Inca". PBS. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Todd, Margo (2004). "Dorislaus, Isaac (1595–1649)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7832. Retrieved 24 October 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Spencer, Charles, Killers of the King: The Men Who Dared to Execute Charles I p 33

- Kenyon, J.P. (2000). The Popish Plot. Phoenix Press reissue.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Top 10 Composers Who Died Unnatural or Odd Deaths". Listverse. 21 May 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- "Jean – Marie Leclair (1697–1764) | early-music.com". Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Bradsby, Henry C. (1893). History of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. Chicago: Nelson. p. 1.567. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Post-Dispatch, TIM O'NEIL St Louis. "Nov. 7, 1837 • A crusading editor is killed defending the freedom of the press". stltoday.com. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (Paperback ed.). New York: Cooper Square Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7.

- "Helen Jewett: The newspapers of 1836 were transfixed by the story of a prostitute murdered by a client". The Vintage News. 2017-06-01. Retrieved 2020-05-11.

- "Duchess de Choiseul-Praslin: Her Murder in 1847". Geri Walton. 19 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Gombrich, Marius, "Crime scene investigation: Edo: Samurai Sakamoto Ryoma's murder scene makes a grisly but fascinating show", Japan Times, 7 May 2010, p. 15.

- National Diet Library (NDL), Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures, Nakaoka, Shintaro

- "5 of Japan's Most Famous Unsolved Crimes". Tokyo Weekender. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "HINDMAN, Thomas Carmichael". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Rogers, William Warren (2 January 2013). "The Boyd Incident: Black Belt Violence During Reconstruction". Civil War History. 21 (4): 309–329. doi:10.1353/cwh.1975.0009. ISSN 1533-6271.

- Nathan-Kazis, Benjamin (13 January 2010). "A Death in the Family". Tablet. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Juan Prim, 1st Marquis of los Castillejos – Facts, Bio, Family, Life, Info". Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "A Double Crime". Illinois State Register. 29 April 1871. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Ames, John Edward (2004). The Real Deadwood: True Life Histories of Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, Outlaw Towns, and Other Characters of the Lawless West. Penguin. ISBN 9781596090316.

- Ross, Greg (12 January 2011). "An Obscure Exit". futilitycloset.com. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- Congressional Record, V. 153, Part 19, October 1, 2007 to October 16, 2007. Government Printing Office.

- "DeFoor". atlantasupperwestside.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "Canadian Mysteries, The Massacre of the "Black" Donnellys". Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- "PressReader.com – Your favorite newspapers and magazines". pressreader.com. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- admin (14 March 2015). "History". Rahway Police Department. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- "1211UFNJ". doenetwork.org. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- "The Westminster Mystery", Morning Advertiser, 23 October 1888, retrieved 21 April 2019

- "John Middleton Clayton (1840–1889)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "Truth Dims the Legend of Outlaw Queen Belle Starr". Los Angeles Times. 2002-02-17. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "FrontierTimes – Outlaws – Belle Starr". www.frontiertimes.com. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "The Trial of Lizzie Borden". University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Finnegan, Terence (2013). A Deed So Accursed: Lynching in Mississippi and South Carolina, 1881–1940. American South series. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. pp. 50–55. ISBN 978-0-8139-3385-6. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- Whiticker, Alan J. (2005). Twelve Crimes That Shocked the Nation. ISBN 1-74110-110-7

- Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). "Goebel Assassination". The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

External links

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.