Ötzi

Ötzi, also called the Iceman, is the natural mummy of a man who lived between 3400 and 3100 BCE. The mummy was found in September 1991 in the Ötztal Alps (hence the nickname "Ötzi") on the border between Austria and Italy.

Ötzi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pronunciation | German pronunciation: [ˈœtsi] ( |

| Born | c. 3345 BCE |

| Died | c. 3300 BCE (aged about 45) Ötztal Alps, near Hauslabjoch on the border between Austria and Italy |

| Other names | Ötzi the Iceman Similaun Man Man from Hauslabjoch Hauslabjoch mummy Frozen Man Frozen Fritz[1][2] Tyrolean Iceman Similaun Man (Italian: Mummia del Similaun) |

| Known for | Oldest natural mummy of a Chalcolithic (Copper Age) European man |

| Height | 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in) |

| Website | South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology |

Ötzi is believed to have been murdered; an arrowhead has been found in his left shoulder, which would have caused a fatal wound. The nature of his life and the circumstances of his death are the subject of much investigation and speculation.

He is Europe's oldest known natural human mummy and has offered an unprecedented view of Chalcolithic (Copper Age) Europeans. His body and belongings are displayed in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, South Tyrol, Italy.

Discovery

Ötzi was found on 19 September 1991 by two German tourists, at an elevation of 3,210 metres (10,530 ft) on the east ridge of the Fineilspitze in the Ötztal Alps on the Austrian–Italian border, near Similaun mountain and the Hauslabjoch pass. The tourists, Helmut and Erika Simon, were walking off the path between Hauslabjoch and Tisenjoch, another pass. At first, they believed that the body was of a recently deceased mountaineer.[3] The next day, a mountain gendarme and the keeper of the nearby Similaunhütte first attempted to remove the body, which was frozen in ice below the torso, using a pneumatic drill and ice-axes, but had to give up due to bad weather. Within a short time, eight groups visited the site, among whom were mountaineers Hans Kammerlander and Reinhold Messner. The body was semi-officially extracted on 22 September and officially salvaged the following day. It was transported to the office of the medical examiner in Innsbruck, together with other objects found. On 24 September, the find was examined there by archaeologist Konrad Spindler of the University of Innsbruck. He dated the find to be "about four thousand years old" on the basis of the typology of an axe among the retrieved objects.[4][5]

Border dispute

At the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye of 1919, the border between North and South Tyrol was defined as the watershed of the rivers Inn and Etsch. Near Tisenjoch the glacier (which has since retreated) complicated establishing the watershed and the border was drawn too far north. Although Ötzi's find site drains to the Austrian side, surveys in October 1991 showed that the body had been located 92.56 m (101.22 yd) inside Italian territory as delineated in 1919.[6] The province of South Tyrol claimed property rights but agreed to let Innsbruck University finish its scientific examinations. Since 1998, it has been on display at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, the capital of South Tyrol.[7]

Scientific analyses

The corpse has been extensively examined, measured, X-rayed, and dated. Tissues and intestinal contents have been examined microscopically, as have the items found with the body. In August 2004, frozen bodies of three Austro-Hungarian soldiers killed during the Battle of San Matteo (1918) were found on the mountain Punta San Matteo in Trentino. One body was sent to a museum in the hope that research on how the environment affected its preservation would help unravel Ötzi's past.[8]

Body

By current estimates (2016), at the time of his death, Ötzi was 160 centimetres (5 ft 3 in) tall, weighed about 50 kilograms (110 lb), and was about 45 years of age.[9] When his body was found, it weighed 13.750 kilograms (30 lb 5.0 oz).[10][11] Because the body was covered in ice shortly after his death, it had only partially deteriorated. Initial reports claimed that his penis and most of his scrotum were missing, but this was later shown to be unfounded.[12] Analysis of pollen, dust grains and the isotopic composition of his tooth enamel indicates that he spent his childhood near the present village of Feldthurns, north of Bolzano, but later went to live in valleys about 50 kilometres farther north.[13]

In 2009, a CAT scan revealed that the stomach had shifted upward to where his lower lung area would normally be. Analysis of the contents revealed the partly digested remains of ibex meat, confirmed by DNA analysis, suggesting he had a meal less than two hours before his death. Wheat grains were also found.[14] It is believed that Ötzi most likely had a few slices of a dried, fatty meat, probably bacon, which came from a wild goat in South Tyrol, Italy.[15] Analysis of Ötzi's intestinal contents showed two meals (the last one consumed about eight hours before his death), one of chamois meat, the other of red deer and herb bread; both were eaten with roots and fruits. The grain also eaten with both meals was a highly processed einkorn wheat bran,[16] quite possibly eaten in the form of bread. In the proximity of the body, and thus possibly originating from the Iceman's provisions, chaff and grains of einkorn and barley, and seeds of flax and poppy were discovered, as well as kernels of sloes (small plum-like fruits of the blackthorn tree) and various seeds of berries growing in the wild.[17]

Hair analysis was used to examine his diet from several months before. Pollen in the first meal showed that it had been consumed in a mid-altitude conifer forest, and other pollens indicated the presence of wheat and legumes, which may have been domesticated crops. Pollen grains of hop-hornbeam were also discovered. The pollen was very well preserved, with the cells inside remaining intact, indicating that it had been fresh (estimated about two hours old) at the time of Ötzi's death, which places the event in the spring or early summer. Einkorn wheat is harvested in the late summer, and sloes in the autumn; these must have been stored from the previous year.[18]

High levels of both copper particles and arsenic were found in Ötzi's hair. This, along with Ötzi's copper axe blade, which is 99.7% pure copper, has led scientists to speculate that Ötzi was involved in copper smelting.[19]

By examining the proportions of Ötzi's tibia, femur and pelvis, Christopher Ruff has determined that Ötzi's lifestyle included long walks over hilly terrain. This degree of mobility is not characteristic of other Copper Age Europeans. Ruff proposes that this may indicate that Ötzi was a high-altitude shepherd.[20]

Using modern 3D scanning technology, a facial reconstruction has been created for the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy. It shows Ötzi looking old for his 45 years, with deep-set brown eyes, a beard, a furrowed face, and sunken cheeks. He is depicted looking tired and ungroomed.[21]

Health

Ötzi apparently had whipworm (Trichuris trichiura), an intestinal parasite. During CT scans, it was observed that three or four of his right ribs had been cracked when he had been lying face down after death, or where the ice had crushed his body. One of his fingernails (of the two found) shows three Beau's lines indicating he was sick three times in the six months before he died. The last incident, two months before he died, lasted about two weeks.[22] It was also found that his epidermis, the outer skin layer, was missing, a natural process from his mummification in ice.[23] Ötzi's teeth showed considerable internal deterioration from cavities. These oral pathologies may have been brought about by his grain-heavy, high carbohydrate diet.[24] DNA analysis in February 2012 revealed that Ötzi was lactose intolerant, supporting the theory that lactose intolerance was still common at that time, despite the increasing spread of agriculture and dairying.[25]

Skeletal details and tattooing

Ötzi had a total of 61 tattoos, consisting of 19 groups of black lines ranging from 1 to 3 mm in thickness and 7 to 40 mm long.[26] These include groups of parallel lines running along the longitudinal axis of his body and to both sides of the lumbar spine, as well as a cruciform mark behind the right knee and on the right ankle, and parallel lines around the left wrist. The greatest concentration of markings is found on his legs, which together exhibit 12 groups of lines.[27] A microscopic examination of samples collected from these tattoos revealed that they were created from pigment manufactured out of fireplace ash or soot.[28] This pigment was then rubbed into small linear incisions or punctures.[29] It has been suggested that Ötzi has been repeatedly tattooed in the same locations, since the majority of them are quite dark.[30]

Radiological examination of Ötzi's bones showed "age-conditioned or strain-induced degeneration" corresponding to many tattooed areas, including osteochondrosis and slight spondylosis in the lumbar spine and wear-and-tear degeneration in the knee and especially in the ankle joints.[31] It has been speculated that these tattoos may have been related to pain relief treatments similar to acupressure or acupuncture.[27] If so, this is at least 2,000 years before their previously known earliest use in China (c. 1000 BCE).[32] It has been shown that 9 out of the 19 groups of his tattoos are located next to, or directedly on acupunctural areas that are used today. The majority of the other tattoos are on meridians, other acupunctural areas of the body, or over arthritic joints. For example, the tattoos on his upper chest are placed on acupunctural locations that help with abdominal pain. Since it is presumed Ötzi had whipworm, which would cause said intestinal pain, such tattoos could have helped him feel some relief, which supports the theory that they were used for therapeutic purposes.[33][29]

At one point, research into archaeological evidence for ancient tattooing confirmed that Ötzi was the oldest tattooed human mummy yet discovered.[34][35] In 2018, however, nearly contemporaneous tattooed mummies were discovered in Egypt.[36]

Many of Ötzi's tattoos originally went unnoticed since they are difficult to see with the naked eye. In 2015, researchers photographed the body using noninvasive multispectral techniques to capture images on different light wavelengths that are imperceivable by humans, revealing the remainder of his tattoos. [33][29]

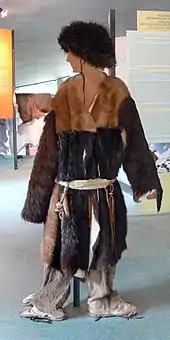

Clothes and shoes

Ötzi wore a cloak made of woven grass[37] and a coat, a belt, a pair of leggings, a loincloth and shoes, all made of leather of different skins. He also wore a bearskin cap with a leather chin strap. The shoes were waterproof and wide, seemingly designed for walking across the snow; they were constructed using bearskin for the soles, deer hide for the top panels, and a netting made of tree bark. Soft grass went around the foot and in the shoe and functioned like modern socks. The coat, belt, leggings and loincloth were constructed of vertical strips of leather sewn together with sinew. His belt had a pouch sewn to it that contained a cache of useful items: a scraper, drill, flint flake, bone awl and a dried fungus.[38]

The shoes have since been reproduced by a Czech academic, who said that "because the shoes are actually quite complex, I'm convinced that even 5,300 years ago, people had the equivalent of a cobbler who made shoes for other people". The reproductions were found to constitute such excellent footwear that it was reported that a Czech company offered to purchase the rights to sell them.[39] However, a more recent hypothesis by British archaeologist Jacqui Wood says that Ötzi's shoes were actually the upper part of snowshoes. According to this theory, the item currently interpreted as part of a backpack is actually the wood frame and netting of one snowshoe and animal hide to cover the face.[40]

The leather loincloth and hide coat were made from sheepskin. Genetic analysis showed that the sheep species was nearer to modern domestic European sheep than to wild sheep; the items were made from the skins of at least four animals. Part of the coat was made from domesticated goat belonging to a mitochondrial haplogroup (a common female ancestor) that inhabits central Europe today. The coat was made from several animals from two different species and was stitched together with hides available at the time. The leggings were made from domesticated goat leather. A similar set of 6,500-year-old leggings discovered in Switzerland were made from goat leather which may indicate the goat leather was specifically chosen.

Shoelaces were made from the European genetic population of cattle. The quiver was made from wild roe deer, the fur hat was made from a genetic lineage of brown bear which lives in the region today. Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers from Ireland and Italy reported their analysis of his clothing's mitochondrial DNA, which was extracted from nine fragments from six of his garments, including his loin cloth and fur cap.[41][42][43]

Tools and equipment

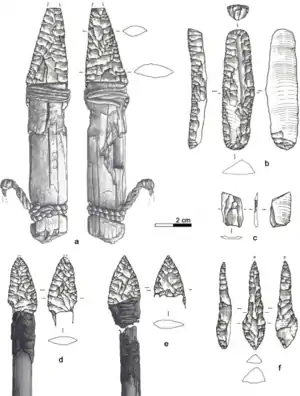

a) Dagger, b) Endscraper, c) Borer, d) Arrowhead 14, e) Arrowhead 12, f) Small flake [44]

Other items found with the Iceman were a copper axe with a yew handle, a chert-bladed knife with an ash handle and a quiver of 14 arrows with viburnum and dogwood shafts.[45][46] Two of the arrows, which were broken, were tipped with flint and had fletching (stabilizing fins), while the other 12 were unfinished and untipped. The arrows were found in a quiver with what is presumed to be a bow string, an unidentified tool, and an antler tool which might have been used for sharpening arrow points.[47] There was also an unfinished yew longbow that was 1.82 metres (72 in) long.[48]

In addition, among Ötzi's possessions were berries, two birch bark baskets, and two species of polypore mushrooms with leather strings through them. One of these, the birch fungus, is known to have anthelmintic properties, and was probably used for medicinal purposes.[49] The other was a type of tinder fungus, included with part of what appeared to be a complex firelighting kit. The kit featured pieces of over a dozen different plants, in addition to flint and pyrite for creating sparks.

Ötzi's copper axe was of particular interest. His axe's haft is 60 centimetres (24 in) long and made from carefully worked yew with a right-angled crook at the shoulder, leading to the blade. The 9.5 centimetres (3.7 in) long axe head is made of almost pure copper, produced by a combination of casting, cold forging, polishing, and sharpening. Despite the fact that copper ore sources in the Alpines are known to have been exploited at the time, a study indicated that the copper in the axe came from southern Tuscany.[50] It was let into the forked end of the crook and fixed there using birch-tar and tight leather lashing. The blade part of the head extends out of the lashing and shows clear signs of having been used to chop and cut. At the time, such an axe would have been a valuable possession, important both as a tool and as a status symbol for the bearer.[51]

Genetic analysis

Ötzi's full genome has been sequenced; the report on this was published on 28 February 2012.[52] The Y chromosome DNA of Ötzi belongs to a subclade of G defined by the SNPs M201, P287, P15, L223 and L91 (G-L91, ISOGG G2a2b, former "G2a4"). He was not typed for any of the subclades downstreaming from G-L91; however, an analysis of his BAM file revealed that he belongs to the L166 and FGC5672 subclades below L91.[53] G-L91 is now mostly found in South Corsica.[54]

Analysis of his mitochondrial DNA showed that Ötzi belongs to the K1 subclade, but cannot be categorized into any of the three modern branches of that subclade (K1a, K1b or K1c). The new subclade has provisionally been named K1ö for Ötzi.[55] A multiplex assay study was able to confirm that the Iceman's mtDNA belongs to a previously unknown European mtDNA clade with a very limited distribution among modern data sets.[56]

By autosomal DNA, Ötzi is most closely related to Southern Europeans, especially to geographically isolated populations like Corsicans and Sardinians.[57][58][59][60]

DNA analysis also showed him at high risk of atherosclerosis and lactose intolerance, with the presence of the DNA sequence of Borrelia burgdorferi, possibly making him the earliest known human with Lyme disease.[52][61] A later analysis suggested the sequence may have been a different Borrelia species.[62]

In October 2013, it was reported that 19 modern Tyrolean men were descendants of Ötzi or of a close relative of Ötzi. Scientists from the Institute of Legal Medicine at Innsbruck Medical University had analysed the DNA of over 3,700 Tyrolean male blood donors and found 19 who shared a particular genetic mutation with the 5,300-year-old man.[63]

Blood

In May 2012, scientists announced the discovery that Ötzi still had intact blood cells. These are the oldest complete human blood cells ever identified. In most bodies this old, the blood cells are either shrunken or mere remnants, but Ötzi's have the same dimensions as living red blood cells and resembled a modern-day sample.[64][65]

H. pylori analysis

In 2016, researchers reported on a study from the extraction of twelve samples from the gastrointestinal tract of Ötzi to analyze the origins of the Helicobacter pylori in his gut.[66] The H. pylori strain found in his gastrointestinal tract was, surprisingly, the hpAsia2 strain, a strain today found primarily in South Asian and Central Asian populations, with extremely rare occurrences in modern European populations.[66] The strain found in Ötzi's gut is most similar to three modern individuals from Northern India; the strain itself is, of course, older than the modern Northern Indian strain.[66]

Stomach

Ötzi's stomach was completely full and its contents were mostly undigested. In 2018, researchers performed a thorough analysis of his stomach and intestines to gain insights on Chalcolithic meal composition and dietary habits. Biopsies were performed on the stomach to obtain dietary information in the time leading up to his death, and the contents themselves were also analyzed. Previously, Ötzi was believed to be vegetarian, but during this study it was revealed that his diet was omnivorous. The presence of certain compounds suggest what kinds of food he generally ate, such as gamma-terpinene implying the intake of herbs, and several nutritious minerals indicating red meat or dairy consumption. Through analysis of DNA and protein traces, the researchers were able to identify the contents of Ötzi's last meal. It was well balanced and was composed of three major components, fat and meat from ibex and red deer as well as grain cereals created from einkorn. The results of atomic force microscopy and Raman spectroscopy analysis reveal that he consumed fresh or dried wild meat. A previous study detected charcoal particles in his lower intestine which indicate that fire is present during some part of the food preparation process, but it is likely used in drying out the meat or smoking it.[67][68]

Cause of death

The cause of death remained uncertain until 10 years after the discovery of the body.[69] It was initially believed that Ötzi died from exposure during a winter storm. Later it was speculated that Ötzi might have been a victim of a ritual sacrifice, perhaps for being a chieftain.[70][71] This explanation was inspired by theories previously advanced for the first millennium BCE bodies recovered from peat bogs such as the Tollund Man and the Lindow Man.[71]

Arrowhead and blood analyses

In 2001, X-rays and a CT scan revealed that Ötzi had an arrowhead lodged in his left shoulder when he died[72] and a matching small tear on his coat.[73] The discovery of the arrowhead prompted researchers to theorize Ötzi died of blood loss from the wound, which would probably have been fatal even if modern medical techniques had been available.[74] Further research found that the arrow's shaft had been removed before death, and close examination of the body found bruises and cuts to the hands, wrists and chest and cerebral trauma indicative of a blow to the head. One of the cuts was to the base of his thumb that reached down to the bone but had no time to heal before his death. Currently, it is believed that Ötzi bled to death after the arrow shattered the scapula and damaged nerves and blood vessels before lodging near the lung.[75]

Recent DNA analyses are claimed to have revealed traces of blood from at least four other people on his gear: one from his knife, two from a single arrowhead, and a fourth from his coat.[76][77] Interpretations of these findings were that Ötzi killed two people with the same arrow and was able to retrieve it on both occasions, and the blood on his coat was from a wounded comrade he may have carried over his back.[73] Ötzi's posture in death (frozen body, face down, left arm bent across the chest) could support a theory that before death occurred and rigor mortis set in, the Iceman was turned onto his stomach in the effort to remove the arrow shaft.[78]

Alternate theory of death

In 2010, it was proposed that Ötzi died at a much lower altitude and was buried higher in the mountains, as posited by archaeologist Alessandro Vanzetti of the Sapienza University of Rome and his colleagues.[79] According to their study of the items found near Ötzi and their locations, it is possible that the iceman may have been placed above what has been interpreted as a stone burial mound but was subsequently moved with each thaw cycle that created a flowing watery mix driven by gravity before being re-frozen.[80] While archaeobotanist Klaus Oeggl of the University of Innsbruck agrees that the natural process described probably caused the body to move from the ridge that includes the stone formation, he pointed out that the paper provided no compelling evidence to demonstrate that the scattered stones constituted a burial platform.[80] Moreover, biological anthropologist Albert Zink argues that the iceman's bones display no dislocations that would have resulted from a downhill slide and that the intact blood clots in his arrow wound would show damage if the body had been moved up the mountain.[80] In either case, the burial theory does not contradict the possibility of a violent cause of death.

Legal dispute

Italian law entitled the Simons to a finders' fee from the South Tyrolean provincial government of 25% of the value of Ötzi. In 1994 the authorities offered a "symbolic" reward of 10 million lire (€5,200), which the Simons declined.[81] In 2003, the Simons filed a lawsuit which asked a court in Bolzano to recognize their role in Ötzi's discovery and declare them his "official discoverers". The court decided in the Simons' favor in November 2003, and at the end of December that year the Simons announced that they were seeking US$300,000 as their fee. The provincial government decided to appeal.[82]

In addition, two people came forward to claim that they were part of the same mountaineering party that came across Ötzi and discovered the body first:

- Magdalena Mohar Jarc, a retired Slovenian climber, who alleged that she discovered the corpse first after falling into a crevice, and shortly after returning to a mountain hut, asked Helmut Simon to take photographs of Ötzi. She cited Reinhold Messner, who was also present in the mountain hut, as the witness to this.[83]

- Sandra Nemeth, from Switzerland, who contended that she found the corpse before Helmut and Erika Simon, and that she spat on Ötzi to make sure that her DNA would be found on the body later. She asked for a DNA test on the remains, but experts believed that there was little chance of finding any trace.[84]

In 2005 the rival claims were heard by a Bolzano court. The legal case angered Mrs. Simon, who alleged that neither woman was present on the mountain that day.[84] In 2005, Mrs. Simon's lawyer said: "Mrs. Simon is very upset by all this and by the fact that these two new claimants have decided to appear 14 years after Ötzi was found."[84] In 2008, however, Jarc stated for a Slovene newspaper that she wrote twice to the Bolzano court in regard to her claim but received no reply whatsoever.[83]

In 2004, Helmut Simon died. Two years later, in June 2006, an appeals court affirmed that the Simons had indeed discovered the Iceman and were therefore entitled to a finder's fee. It also ruled that the provincial government had to pay the Simons' legal costs. After this ruling, Mrs. Erika Simon reduced her claim to €150,000. The provincial government's response was that the expenses it had incurred to establish a museum and the costs of preserving the Iceman should be considered in determining the finder's fee. It insisted it would pay no more than €50,000. In September 2006, the authorities appealed the case to Italy's highest court, the Court of Cassation.[82]

On 29 September 2008 it was announced that the provincial government and Mrs. Simon had reached a settlement of the dispute, under which she would receive €150,000 in recognition of Ötzi's discovery by her and her late husband and the tourist income that it attracts.[81][85]

"Ötzi's curse"

Influenced by the "Curse of the pharaohs" and the media theme of cursed mummies, claims have been made that Ötzi is cursed. The allegation revolves around the deaths of several people connected to the discovery, recovery and subsequent examination of Ötzi. It is alleged that they have died under mysterious circumstances. These people include co-discoverer Helmut Simon[86] and Konrad Spindler, the first examiner of the mummy in Austria in 1991.[87] To date, the deaths of seven people, of which four were accidental, have been attributed to the alleged curse. In reality hundreds of people were involved in the recovery of Ötzi and are still involved in studying the body and the artifacts found with it. The fact that a small percentage of them have died over the years has not been shown to be statistically significant.[88][89]

See also

- Children of Llullaillaco

- Gebelein predynastic mummies

- Iceman - a 2017 fictional film about the life of Ötzi

- List of human evolution fossils

- List of unsolved murders

- Lovers of Valdaro

- Mummy Juanita

- Saltmen

- Tarim Basin Mummies

References

- Farid Chenoune (15 February 2005). Carried Away: All About Bags. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-86565-158-6.

- Joachim Chwaszcza; Brian Bell (1 April 1993). Italian Alps, South Tyrol. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-65772-0.

- Description of the Discovery Archived 13 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology web site

- Brenda Fowler (2001). Iceman: Uncovering the Life and Times of a Prehistoric Man Found in an Alpine Glacier. University of Chicago Press. p. 37 ff. ISBN 978-0-226-25823-2.

- "The Incredible Age of the Find". South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology. 2013. Archived from the original on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- The Border Question Archived 8 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, at the museum site

- Brida, Juan Gabriel; Meleddu, Marta; Pulina, Manuela (1 November 2012). "Understanding Urban Tourism Attractiveness: The Case of the Archaeological Ötzi Museum in Bolzano". Journal of Travel Research. 51 (6): 730–741. doi:10.1177/0047287512437858. ISSN 0047-2875. S2CID 154672981.

- "WWI bodies are found on glacier", BBC News, 23 August 2004, archived from the original on 30 June 2006

- Rory Carroll (26 September 2000), "Iceman is defrosted for gene tests: New techniques may link Copper Age shepherd to present-day relatives", The Guardian

- transcript. "Iceman Reborn". PBS. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Egarter-Vigl, Eduard (2006), "The Preservation of the Iceman Mummy", in Marco Samadelli (ed.), The Chalcolithic Mummy, Volume 3, In Search of Immortality, Folio Verlag, p. 54, ISBN 978-3-85256-337-4

- Hays, Jeffrey. "OTZI, THE ICEMAN - Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Wolfgang Müller, et al. (31 October 2003), "Origin and Migration of the Alpine Iceman", Science, 302 (5646): 862–866, Bibcode:2003Sci...302..862M, doi:10.1126/science.1089837, PMID 14593178, S2CID 21923588, lay summary – Mummy Tombs (16 December 2007)

- Than, Ker (23 June 2011). "Iceman's Stomach Sampled—Filled With Goat Meat". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 26 June 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- "Iceman Oetzi's last meal was 'Stone Age bacon'". Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- T.G. Holden (2002), "The Food Remains from the Colon of the Tyrolean Ice Man", in Keith Dobney; Terry O'Connor (eds.), Bones and the Man: Studies in Honour of Don Brothwell, Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 35–40, ISBN 978-1-84217-060-1

- A.G. Heiss & K. Oeggl (19 February 2008), "The plant macro-remains from the Iceman site (Tisenjoch, Italian-Austrian border, eastern Alps): new results on the glacier mummy's environment", Veget Hist Archaeobot, 18: 23–35, doi:10.1007/s00334-007-0140-8, S2CID 14519658

- Bortenschlager, Sigmar; Oeggl, Klaus (6 December 2012). The Iceman and his Natural Environment: Palaeobotanical Results. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-7091-6758-8.

- <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (16 September 2002), "Iceman's final meal", BBC News, archived from the original on 30 March 2015

- Christopher Ruff; Holt, BM; Sládek, V; Berner, M; Murphy Jr, WA; Zur Nedden, D; Seidler, H; Recheis, W (July 2006), "Body size, body proportions, and mobility in the Tyrolean "Iceman"", Journal of Human Evolution, 51 (1): 91–101, doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.02.001, PMID 16549104

- Lorenzi, Rossella (25 February 2011). "The Iceman Mummy: Finally Face to Face". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- James H. Dickson; Klaus Oeggl; Linda L. Handly (May 2003), "The Iceman Reconsidered" (PDF), Scientific American, 288 (5): 70–79, Bibcode:2003SciAm.288e..70D, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0503-70, PMID 12701332, archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2008

- James M. Deem (3 January 2008), Ötzi: Iceman of the Alps: His health, Mummy Tombs, archived from the original on 13 November 2006, retrieved 6 January 2008

- "Iceman Had Bad Teeth : Discovery News". News.discovery.com. 15 June 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Iceman Lived a While After Arrow Wound". DNews. 10 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012.

- Samadelli, M; M Melis; M Miccoli; E Egarter-Vigl; AR Zink (2015), "Complete Mapping of the Tattoos of the 5300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman", Journal of Cultural Heritage, 16 (5): 753–758, doi:10.1016/j.culher.2014.12.005

- Deter-Wolf, Aaron (22 January 2015). "Scan finds new tattoos on 5300-year-old Iceman". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Pabst, M.A.; I Letofsky-Papst; E Bock; M Moser; L Dorfer; E Egarter-Vigl; F Hoffer (2009), "The Tattoos of the Tyrolean Iceman: A Light Microscopical, Ultrastructural and Element Analytical Study", Journal of Archaeological Science, 36 (10): 2335–2341, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.06.016

- Piombino-Mascali, Dario; Krutak, Lars (2020), Sheridan, Susan Guise; Gregoricka, Lesley A. (eds.), "Therapeutic Tattoos and Ancient Mummies: The Case of the Iceman", Purposeful Pain: The Bioarchaeology of Intentional Suffering, Bioarchaeology and Social Theory, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 119–136, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-32181-9_6, ISBN 978-3-030-32181-9, retrieved 5 December 2020

- Piombino-Mascali, Dario; Krutak, Lars (2020), Sheridan, Susan Guise; Gregoricka, Lesley A. (eds.), "Therapeutic Tattoos and Ancient Mummies: The Case of the Iceman", Purposeful Pain: The Bioarchaeology of Intentional Suffering, Bioarchaeology and Social Theory, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 119–136, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-32181-9_6, ISBN 978-3-030-32181-9, retrieved 5 December 2020

- Spindler, Konrad (1995), The man in the ice, Phoenix, pp. 178–184, ISBN 978-0-7538-1260-0

- Dorfer, L; M Moser; F Bahr; K Spindler; E Egarter-Vigl; S Giullén; G Dohr; T Kenner (September 1999), "A medical report from the stone age?", The Lancet, 354 (9183): 1023–1025, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)12242-0, PMID 10501382, S2CID 29084491

- Zink, Albert; Samadelli, Marco; Gostner, Paul; Piombino-Mascali, Dario (1 June 2019). "Possible evidence for care and treatment in the Tyrolean Iceman". International Journal of Paleopathology. 25: 110–117. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2018.07.006. ISSN 1879-9817. PMID 30098946.

- Deter-Wolf, Aaron (11 November 2015). "It's official: Ötzi the Iceman has the oldest tattoos in the world". Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Deter-Wolf, Aaron; Robitaille, Benoît; Krutak, Lars; Galliot, Sébastien (February 2016). "The World's Oldest Tattoos". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 5: 19–24. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.11.007.

- Daley, Jason (5 December 2019). "Infrared Reveals Egyptian Mummies' Hidden Tattoos". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- In the book Cookwise by Shirley Corriher, the point is made (in relation to cooking) that plant leaves have a waterproof, waxy cuticle which makes raindrops roll off, with the comment "it was interesting that the 5,000-year-old Alpine traveler ... had a grass raincoat": Shirley O. Corriher (1997), Cookwise: The Hows and Whys of Successful Cooking, New York, N.Y.: William Morrow and Company, p. 312, ISBN 978-0-688-10229-6

- "The Belt and Pouch". South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- Katka Krosnar (17 July 2005), "Now you can walk in footsteps of 5,000-year-old Iceman – wearing his boots", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 29 June 2011

- Hammond, Norman (21 February 2005). "Iceman was wearing 'earliest snowshoes'". The Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- Davis, Nicola (30 August 2016). "It becometh the iceman: clothing study reveals stylish secrets of leather-loving ancient". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Romey, Kristin (18 August 2016). "Here's What the Iceman Was Wearing When He Died 5,300 Years Ago". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- O’Sullivan, Niall J.; Teasdale, Matthew D.; Mattiangeli, Valeria; Maixner, Frank; Pinhasi, Ron; Bradley, Daniel G.; Zink, Albert (18 August 2016). "A whole mitochondria analysis of the Tyrolean Iceman's leather provides insights into the animal sources of Copper Age clothing". Scientific Reports. 6: 31279. Bibcode:2016NatSR...631279O. doi:10.1038/srep31279. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4989873. PMID 27537861.

- Wierer, U., Arrighi, S., Bertola, S., Kaufmann, G., Baumgarten, B., Pedrotti, A., Pernter, P. and Pelegrin, J. (2018) "The Iceman’s lithic toolkit: Raw material, technology, typology and use". PLOS ONE, 13(6): e0198292. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198292

- "The Final Hours of the Iceman's Tools". Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Petraglia, Michael D.; Wierer, Ursula; Arrighi, Simona; Bertola, Stefano; Kaufmann, Günther; Baumgarten, Benno; Pedrotti, Annaluisa; Pernter, Patrizia; Pelegrin, Jacques (2018). "The Iceman's lithic toolkit: Raw material, technology, typology and use". PLOS ONE. 13 (6): e0198292. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1398292W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198292. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6010222. PMID 29924811.

- Brenda Fowler (2001), Iceman: Uncovering the Life and Times of a Prehistoric Man found in an Alpine Glacier, Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, pp. 105–106, ISBN 978-0-226-25823-2

- Norman Davies (1996), Europe: A History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7

- Capasso L (December 1998), "5300 years ago, the Ice Man used natural laxatives and antibiotics", Lancet, 352 (9143): 1864, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79939-6, PMID 9851424, S2CID 40027370

- Squires, Nick (7 July 2017). "Copper axe owned by Neolithic hunter Ötzi the Iceman came all the way from Tuscany". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "The Axe – Ötzi – South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology". iceman.it. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- Keller, Andreas; Graefen, Angela; et al. (28 February 2012). "New insights into the Tyrolean Iceman's origin and phenotype as inferred by whole-genome sequencing". Nature Communications. 3: 698. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3..698K. doi:10.1038/ncomms1701. PMID 22426219.

- "G-FGC5672 YTree".

- Di Cristofaro, Julie; Mazières, Stéphane; Tous, Audrey; Di Gaetano, Cornelia; Lin, Alice A.; Nebbia, Paul; Piazza, Alberto; King, Roy J.; Underhill, Peter; Chiaroni, Jacques (1 August 2018). "Prehistoric migrations through the Mediterranean basin shaped Corsican Y-chromosome diversity". PLOS ONE. 13 (8): e0200641. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1300641D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200641. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6070208. PMID 30067762.

- Ermini, Luca; Olivieri, Cristina; Rizzi, Ermanno; Corti, Giorgio; Bonnal, Raoul; Soares, Pedro; Luciani, Stefania; Marota, Isolina; De Bellis, Gianluca; Richards, Martin B.; Rollo, Franco (2008). "Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequence of the Tyrolean Iceman". Current Biology. 18 (21): 1687–93. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.028. PMID 18976917. S2CID 13983702.

- Endicott, Phillip; Sanchez, Juan J; Pichler, Irene; Brotherton, Paul; Brooks, Jerome; Egarter-Vigl, Eduard; Cooper, Alan; Pramstaller, Peter (2009). "Genotyping human ancient mtDNA control and coding region polymorphisms with a multiplexed Single-Base-Extension assay: The singular maternal history of the Tyrolean Iceman". BMC Genetics. 10: 29. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-10-29. PMC 2717998. PMID 19545382.

- "Ancient DNA reveals genetic relationship between today's Sardinians and Neolithic Europeans – HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology". 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Keller, Andreas; Graefen, Angela; Ball, Markus; Matzas, Mark; Boisguerin, Valesca; Maixner, Frank; Leidinger, Petra; Backes, Christina; Khairat, Rabab; Forster, Michael; Stade, Björn; Franke, Andre; Mayer, Jens; Spangler, Jessica; McLaughlin, Stephen; Shah, Minita; Lee, Clarence; Harkins, Timothy T.; Sartori, Alexander; Moreno-Estrada, Andres; Henn, Brenna; Sikora, Martin; Semino, Ornella; Chiaroni, Jacques; Rootsi, Siiri; Myres, Natalie M.; Cabrera, Vicente M.; Underhill, Peter A.; Bustamante, Carlos D.; et al. (2012). "New insights into the Tyrolean Iceman's origin and phenotype as inferred by whole-genome sequencing". Nature Communications. 3: 698. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3..698K. doi:10.1038/ncomms1701. PMID 22426219.

- Callaway, Ewen (2012). "Iceman's DNA reveals health risks and relations". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.10130. S2CID 85055245. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- "Tratti genetici comuni tra la mummia Oetzi e gli attuali abitanti di Sardegna e Corsica". Tiscali. 28 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012.

- Hall, Stephen S. (November 2011). "Iceman Autopsy". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Ames, S. K.; Hysom, D. A.; Gardner, S. N.; Lloyd, G. S.; Gokhale, M. B.; Allen, J. E. (4 July 2013). "Scalable metagenomic taxonomy classification using a reference genome database". Bioinformatics. 29 (18): 2253–2260. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt389. PMC 3753567. PMID 23828782.

- "Link to Oetzi the Iceman found in living Austrians". BBC News. 10 October 2013. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Owen, James (2 May 2012). "World's Oldest Blood Found in Famed "Iceman" Mummy". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Janko, Marek; Stark, Robert W.; Zink, Albert (7 October 2012). "Preservation of 5300 year old red blood cells in the Iceman". Journal of the Royal Society, Interface. 9 (75): 2581–2590. doi:10.1098/rsif.2012.0174. ISSN 1742-5662. PMC 3427508. PMID 22552923.

- Maixner, Frank; Krause-Kyora, Ben (8 January 2016). "The 5300-year-old Helicobacter pylori genome of the Iceman". Science. 351 (6269): 162–165. Bibcode:2016Sci...351..162M. doi:10.1126/science.aad2545. PMC 4775254. PMID 26744403.

- Maixner, Frank; Turaev, Dmitrij; Cazenave-Gassiot, Amaury; Janko, Marek; Krause-Kyora, Ben; Hoopmann, Michael R.; Kusebauch, Ulrike; Sartain, Mark; Guerriero, Gea; o'Sullivan, Niall; Teasdale, Matthew; Cipollini, Giovanna; Paladin, Alice; Mattiangeli, Valeria; Samadelli, Marco; Tecchiati, Umberto; Putzer, Andreas; Palazoglu, Mine; Meissen, John; Lösch, Sandra; Rausch, Philipp; Baines, John F.; Kim, Bum Jin; An, Hyun-Joo; Gostner, Paul; Egarter-Vigl, Eduard; Malfertheiner, Peter; Keller, Andreas; Stark, Robert W.; et al. (23 July 2018). "The Iceman's Last Meal Consisted of Fat, Wild Meat, and Cereals". Current Biology. 28 (14): 2348–2355.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.067. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 6065529. PMID 30017480.

- Zink, Albert R.; Maixner, Frank (2019). "The Current Situation of the Tyrolean Iceman". Gerontology. 65 (6): 699–706. doi:10.1159/000501878. ISSN 0304-324X. PMID 31505504. S2CID 202555446.

- "Who Killed the Iceman? Clues Emerge in a Very Cold Case". The New York Times. 26 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Sarah Ives (30 October 2003), Was ancient alpine "Iceman" killed in battle?, National Geographic News, archived from the original on 15 October 2007, retrieved 25 October 2007

- Franco Rollo [], et al. (2002), "Ötzi's last meals: DNA analysis of the intestinal content of the Neolithic glacier mummy from the Alps", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99 (20): 12594–12599, Bibcode:2002PNAS...9912594R, doi:10.1073/pnas.192184599, PMC 130505, PMID 12244211

- Stephanie Pain (26 July 2001), Arrow points to foul play in ancient iceman's death, NewScientistTech, archived from the original on 23 August 2014

- James M. Deem (3 January 2008), Ötzi: Iceman of the Alps: Scientific studies, archived from the original on 2 September 2015, retrieved 6 January 2008

- Alok Jha (7 June 2007), "Iceman bled to death, scientists say", The Guardian, archived from the original on 13 March 2016

- Rory Carroll (21 March 2002). "How Oetzi the Iceman was stabbed in the back and lost his fight for life". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007.

- "USATODAY.com – 'Iceman' was murdered, science sleuths say". usatoday.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012.

- Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (25 September 2015). In the Beginning: An Introduction to Archaeology. Routledge. ISBN 9781317346432. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017.

- Rossella Lorenzi (31 August 2007), Blow to head, not arrow, killed Otzi the iceman, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, archived from the original on 11 October 2007; Nicole Winfield (30 August 2007), Ancient murder mystery takes new turn, NBC News

- A. Vanzetti, M. Vidale, M. Gallinaro, D.W. Frayer, and L. Bondioli. "The iceman as a burial Archived 6 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine."[Antiquity (journal)|Antiquity]. Volume: 84 Number: 325 Page: 681–692. September 2010

- "Prehistoric 'Iceman' gets ceremonial twist Archived 30 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine", Science News, 25 September 2010. (Retrieved 19 September 2010)

- <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (29 September 2008), "'Iceman' row ends after 17 years", BBC News, archived from the original on 30 September 2008

- James M. Deem (September 2008), Ötzi: Iceman of the Alps: Finder's fee lawsuits, Mummy Tombs, archived from the original on 2 November 2008, retrieved 1 October 2008

- "Magdaleni ne bodo plačali za Ötzija" [Magdalena Won't Get Paid for Ötzi]. Slovenske novice (in Slovenian). 9 October 2008. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- Nick Pisa (22 October 2005), "Cold case comes to court – After 5,300 years", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 6 December 2008

- Nick Squires (29 September 2008), "Oetzi The Iceman's discoverers finally compensated: A bitter dispute over the payment of a finder's fee for two hikers who discovered the world famous Oetzi The Iceman mummy has finally been settled", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 2 October 2008

- Reuters in Vienna (19 October 2004), "Iceman's finder missing", The Guardian; Stephen Goodwin (25 October 2004), "Helmut Simon: Finder of a Bronze Age man in the alpine snow [obituary]", The Independent, archived from the original on 1 October 2007, retrieved 18 March 2007

- Barbara McMahon (20 April 2005), "Scientist seen as latest 'victim' of Iceman", The Guardian, archived from the original on 9 December 2007

- "Is there an Ötzi curse?", Ötsi – the Iceman, South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, archived from the original on 21 August 2012, retrieved 15 August 2012,

hundreds of people have worked on the Iceman project, and many years have passed since the corpse was first discovered. It is therefore not remarkable that some of those people have since died.

- The Curse of the Ice Mummy, a television documentary screened on UK Channel 4 on 8 March 2007. See also Kathy Marks (5 November 2005), "Curse of Oetzi the Iceman strikes again", The Independent, archived from the original on 18 May 2007, retrieved 17 March 2007 (also reported as Kathy Marks (5 November 2005), "Curse of Oetzi the Iceman claims another victim", The New Zealand Herald); Nick Squires (5 November 2005), "Seventh victim of the Ice Man's 'curse'", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 11 October 2007

Further reading

Articles

- Dickson, James Holms (28 June 2005), Plants and the Iceman: Ötzi's last journey, Division of Environmental and Evolutionary Biology, Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, retrieved 17 March 2007.

- Fowler, Brenda (November 2002), The Iceman's last meal, NOVA Online, PBS, retrieved 17 March 2007.

- Keller, Andreas (28 February 2012), "New insights into the Tyrolean Iceman's origin and phenotype as inferred by whole-genome sequencing" (PDF), Nature Communications, nature.com, 3: 698, Bibcode:2012NatCo...3..698K, doi:10.1038/ncomms1701, PMID 22426219, retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Kennedy, Frances (26 July 2001), "Oetzi the Neolithic Iceman was killed by an arrow, say scientists", The Independent, archived from the original on 18 May 2007, retrieved 17 March 2007.

- Macintyre, Ben (1 November 2003), "We know Oetzi had fleas, his last supper was steak ... and he died 5,300 years ago", The Times.

- Murphy, William A., Jr.; zur Nedden, Dieter; Gostner, Paul; Knapp, Rudolf; Recheis, Wolfgang; Seidler, Horst (24 January 2003), "The Iceman: Discovery and imaging", Radiology, 226 (3): 614–629, doi:10.1148/radiol.2263020338, ISSN 0033-8419, PMID 12601185. On-line pre-publication version.

Books

- Deem, James (2008), Bodies from the Ice, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, p. 64, ISBN 978-0-618-80045-2

- Bortenschlager, Sigmar; Oeggl, Klaus, eds. (2000), The Iceman and His Natural Environment: Palaeobotanical Results, Wien; New York, N.Y.: Springer, ISBN 978-3-211-82660-7CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link).

- Fowler, Brenda (2000), Iceman: Uncovering the Life and Times of a Prehistoric Man Found in an Alpine Glacier, New York, N.Y.: Random House, ISBN 978-0-679-43167-1.

- Spindler, Konrad (2001), The Man in the Ice: The Preserved Body of a Neolithic Man Reveals the Secrets of the Stone Age, Ewald Osers (trans.), London: Phoenix, ISBN 978-0-7538-1260-0.

- De Marinis, Raffaele C.; Brillante, Giuseppe (1998), La Mummia del Similaun: Ötzi, l'uomo venuto dal ghiaccio [The Mummy of the Similaun: Ötzi, the Man who Came from the Ice], Venice, Italy: Marsilio, ISBN 978-88-317-7073-6 (in Italian)

- Fleckinger, Angelika; Steiner, Hubert (2000) [1998], L'uomo venuto dal ghiaccio [The Man who Came from the Ice], Bolzano, Italy: Folio, ISBN 978-88-86857-03-1 (in Italian)

- Frozen Man

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ötzi. |

| The Wikibook Planet Earth has a page on the topic of: A reflection on sustainability comparing Ötzi's and Simon's deaths, by Benjamin Burger. |

- Official website about Ötzi

- New insights into the Tyrolean Iceman's origin and phenotype as inferred by whole-genome sequencing

- Iceman Photoscan, published by EURAC Research, Institute for Mummies and the Iceman

- "Death of the Iceman" – a synopsis of a BBC Horizon TV documentary first broadcast on 7 February 2002

- Ötzi Links ... Der Mann aus dem Eis vom Hauslabjoch – a list of links to websites about Ötzi in English, German and Italian (last updated 28 January 2006)

- Otzi, the 5,300 Year Old Iceman from the Alps: Pictures & Information (last updated 27 October 2004)

- "Five millennia on, Iceman of Bolzano gives up DNA secrets" Michael Day, The Independent, 2 August 2010

- "The Iceman Mummy: Finally Face to Face High definition image of a reconstruction of Ötzi's face.

- "An Ice Cold Case" RadioLab interviews Albert Zink, Head of EURAC Research and the scientist in charge of Ötzi research.

- "Ötzi's Shoes