SpaceX

Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) is an American aerospace manufacturer and space transportation services company headquartered in Hawthorne, California. It was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the goal of reducing space transportation costs to enable the colonization of Mars.[9][10][11] SpaceX has developed several launch vehicles, as well as the Dragon cargo spacecraft and the Starlink satellite constellation (providing internet access), and has flown humans to the International Space Station on the SpaceX Dragon 2.

SpaceX logo | |

.jpg.webp) SpaceX headquarters in December 2017; plumes from a flight of a Falcon 9 rocket are visible overhead | |

| SpaceX | |

| Type | Private |

| Industry | Aerospace |

| Founded | 6 May 2002[1] |

| Founder | Elon Musk |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | |

| Products | |

| Services | Orbital rocket launch |

| Revenue | |

| Owner | Elon Musk Trust (54% equity; 78% voting control)[3] |

Number of employees | 8,000 (May 2020) |

| Website | www |

| Footnotes / references [4][5][6][7][8] | |

SpaceX's achievements include the first privately funded liquid-propellant rocket to reach orbit (Falcon 1 in 2008),[12] the first private company to successfully launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft (Dragon in 2010), the first private company to send a spacecraft to the International Space Station (Dragon in 2012),[13] the first vertical take-off and vertical propulsive landing for an orbital rocket (Falcon 9 in 2015), the first reuse of an orbital rocket (Falcon 9 in 2017), the first to launch a private spacecraft into orbit around the Sun (Falcon Heavy's payload of a Tesla Roadster in 2018), and the first private company to send astronauts to orbit and to the International Space Station (SpaceX Crew Dragon Demo-2 and SpaceX Crew-1 missions in 2020).[14] As of 31 December 2020, SpaceX has flown 20 [15][16] cargo resupply missions to the International Space Station (ISS) under a partnership with NASA,[17] as well as an uncrewed demonstration flight of the human-rated Dragon 2 spacecraft (Crew Dragon Demo-1) on 2 March 2019, and the first crewed Dragon 2 flight on 30 May 2020.[14]

In December 2015, a Falcon 9 accomplished a propulsive vertical landing. This was the first such achievement by a rocket for orbital spaceflight.[18] In April 2016, with the launch of SpaceX CRS-8, SpaceX successfully vertically landed the first stage on an ocean drone ship landing platform.[19] In May 2016, in another first, SpaceX again landed the first stage, but during a significantly more energetic geostationary transfer orbit (GTO) mission.[20] In March 2017, SpaceX became the first to successfully re-launch and land the first stage of an orbital rocket.[21] In January 2020, with the third launch of the Starlink project, SpaceX became the largest commercial satellite constellation operator in the world.[22][23]

In September 2016, Musk unveiled the Interplanetary Transport System — subsequently renamed Starship — a privately funded launch system to develop spaceflight technology for use in crewed interplanetary spaceflight. In 2017, Musk unveiled an updated configuration of the system which is intended to handle interplanetary missions plus become the primary SpaceX orbital vehicle after the early 2020s, as SpaceX has announced it intends to eventually replace its existing Falcon 9 launch vehicles and Dragon space capsule fleet with Starship, even in the Earth-orbit satellite delivery market.[24][25][26]:24:50–27:05 Starship is planned to be fully reusable and will be the largest rocket ever on its debut, scheduled for the early 2020s.[27][28]

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_cropped.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In 2001, Elon Musk conceptualized Mars Oasis, a project to land a miniature experimental greenhouse and grow plants on Mars. He announced that the project would be "the furthest that life's ever traveled" in an attempt to regain public interest in space exploration and increase the budget of NASA.[29][30][31][32] Musk tried to purchase cheap rockets from Russia but returned empty-handed after failing to find rockets for an affordable price.[33][34]

On the flight home, Musk realized that he could start a company that could build the affordable rockets he needed.[34] According to early Tesla and SpaceX investor Steve Jurvetson,[35] Musk calculated that the raw materials for building a rocket were only 3% of the sales price of a rocket at the time. By applying vertical integration,[33] producing around 85% of launch hardware in-house,[36][37] and the modular approach of modern software engineering, Musk believed SpaceX could cut launch price by a factor of ten and still enjoy a 70% gross margin.[38]

In early 2002, Musk started to look for staff for his new space company, soon to be named SpaceX. Musk approached rocket engineer Tom Mueller (later SpaceX's CTO of propulsion), and invited him to become his business partner. Mueller agreed to work for Musk, and thus SpaceX was born.[39] SpaceX was first headquartered in a warehouse in El Segundo, California. The company grew rapidly, from 160 employees in November 2005 to 8,000 in May 2020, when COO Gwynne Shotwell said she did not expect the company to grow much more to bring Starlink online.[8] In 2016, Musk gave a speech at the International Astronautical Congress, where he explained that the U.S. government regulates rocket technology as an "advanced weapon technology", making it difficult to hire non-Americans.[40]

As of March 2018, SpaceX had over 100 launches on its manifest representing about US$12 billion in contract revenue.[41] The contracts included both commercial and government (NASA/DOD) customers.[42] In late 2013, space industry media quoted Musk's comments on SpaceX "forcing... increased competitiveness in the launch industry", its major competitors in the commercial comsat launch market being Arianespace, United Launch Alliance (ULA), and International Launch Services (ILS).[43] At the same time, Musk also said that the increased competition would "be a good thing for the future of space". Currently, SpaceX is the leading global commercial launch provider measured by manifested launches.[44]

On 30 May 2020, SpaceX successfully launched two NASA astronauts (Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken) into orbit on a Crew Dragon spacecraft during Crew Dragon Demo-2, making SpaceX the first private company to send astronauts to the International Space Station and marking the first crewed launch from American soil in 9 years.[45][46] The mission launched from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) of the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.[47] Crew Dragon Demo-2 successfully docked with the International Space Station on 31 May 2020.[48] Due to the COVID-19 pandemic happening at the same time, proper quarantine procedures (many of which were already in use by NASA decades before the 2020 pandemic) were taken to prevent the astronauts from bringing COVID-19 aboard the ISS.[49][50]

Goals

Musk has stated that one of his goals is to decrease the cost and improve the reliability of access to space, ultimately by a factor of ten.[51] CEO Elon Musk said: "I believe US$500 per pound (US$1100/kg) or less is very achievable".[52] Musk has also stated that he wishes to make space travel available for "almost anyone".[53]

A major goal of SpaceX has been to develop a rapidly reusable launch system. As of March 2013, the publicly announced aspects of this technology development effort include an active test campaign of the low-altitude, low-velocity Grasshopper flight test vehicle,[54][55][56] and a high-altitude, high-speed Falcon 9 post-mission booster return test campaign. In 2015, SpaceX successfully landed the first orbital rocket stage on 21 December 2015.

In 2017, SpaceX formed a subsidiary, The Boring Company,[57] and began work to construct a short test tunnel on and adjacent to the SpaceX headquarters and manufacturing facility, utilizing a small number of SpaceX employees,[58] which was completed in May 2018,[59][60] and opened to the public in December 2018.[61] During 2018, The Boring Company was spun out into a separate corporate entity with 6% of the equity going to SpaceX, less than 10% to early employees, and the remainder of the equity to Elon Musk.[61]

At the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) of 2016, Musk announced his plans to build large spaceships to reach Mars.[62] Using the Starship, Musk planned to send at least two uncrewed cargo ships to Mars in 2022. The first missions would be used to seek out sources of water and build a propellant plant. Musk also planned to fly four additional ships to Mars in 2024 including the first people. From there, additional missions would work to establish a Mars colony.[10][63] These goals, however, are facing delays.[64]

Musk's advocacy for the long-term settlement of Mars goes far beyond what SpaceX projects to build;[65][66][67] successful colonization of Mars would ultimately involve many more economic actors — whether individuals, companies, or governments — to facilitate the growth of the human presence on Mars over many decades.[68][69][70]

Achievements

Major achievements of SpaceX are in the reuse of orbital-class launch vehicles and cost reduction in the space launch industry. Most notable of these being the continued landings and relaunches of the first stage of Falcon 9. As of December 2020, SpaceX has used two separate first-stage boosters, B1049 and B1051, seven times each.[71] SpaceX is defined as a private space company and thus its achievements can also be counted as firsts by a private company.

Achievements of SpaceX in chronological order include:[72]

| Date | Achievement | Flight |

|---|---|---|

| 28 September 2008 | First privately funded liquid-fueled rocket to reach orbit. | Falcon 1 flight 4 |

| 14 July 2009 | First privately developed liquid-fueled rocket to put a commercial satellite in orbit. | RazakSAT on Falcon 1 flight 5 |

| 9 December 2010 | First private company to successfully launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft. | SpaceX Dragon on SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 1 |

| 25 May 2012 | First private company to send a spacecraft to the International Space Station (ISS). | Dragon C2+ |

| 22 December 2015 | First landing of an orbital rocket's first stage on land. | Falcon 9 flight 20 |

| 8 April 2016 | First landing of an orbital rocket's first stage on an ocean platform. | Falcon 9 flight 23 |

| 30 March 2017 | First relaunch and landing of a used orbital first stage.[73] | B1021 on Falcon 9 flight 32 |

| 30 March 2017 | First controlled flyback and recovery of a payload fairing.[74] | Falcon 9 flight 32 |

| 3 June 2017 | First re-flight of a commercial cargo spacecraft.[75] | Dragon C106 on SpaceX CRS-11 mission. |

| 6 February 2018 | First private spacecraft launched into heliocentric orbit. | Elon Musk's Tesla Roadster on Falcon Heavy test flight |

| 2 March 2019 | First private company to send a human-rated spacecraft to space. | Crew Dragon Demo-1, on Falcon 9 flight 69 |

| 3 March 2019 | First private company to autonomously dock a spacecraft to the International Space Station (ISS). | Crew Dragon Demo-1, on Falcon 9 flight 69 |

| 25 July 2019 | First use of a full-flow staged combustion cycle engine (Raptor) in a free flying vehicle.[76] The benefit is a much longer life than conventional engines; it is expected to able to be re-used 1000 times.[77] | Starhopper |

| 11 November 2019 | First reuse of payload fairing. The fairing was from the ArabSat-6A mission in April 2019. | Starlink 1 Falcon 9 launch |

| 30 May 2020 | First private company to send humans into orbit.[78] | Crew Dragon Demo-2 |

| 31 May 2020 | First private company to send humans to the International Space Station (ISS).[79] | Crew Dragon Demo-2 |

| 24 Jan 2021 | Most spacecraft launched into space on a single mission, with 143 satellites.[lower-alpha 1][80] | Transporter-1 on Falcon 9 |

- Excluding the passive objects launched as part of Project West Ford

Accidents

In March 2013, a Dragon spacecraft in orbit developed issues with its thrusters that limited its control capabilities. SpaceX engineers were able to remotely clear the blockages within a short period, and the spacecraft was able to successfully complete its mission to and from the International Space Station.

In late June 2015, CRS-7 launched a Cargo Dragon atop a Falcon 9 to resupply the International Space Station. All telemetry readings were nominal until 2 minutes and 19 seconds into the flight when a loss of helium pressure was detected and a cloud of vapor appeared outside the second stage. A few seconds after this, the second stage exploded. The first stage continued to fly for a few seconds before disintegrating due to aerodynamic forces. The capsule was thrown off and survived the explosion, transmitting data until it was destroyed on impact.[81] Later it was revealed that the capsule could have landed intact if it had software to deploy its parachutes in case of a launch mishap.[82] The problem was discovered to be a failed 2-foot-long steel strut purchased from a supplier [83] to hold a helium pressure vessel that broke free due to the force of acceleration.[84] This caused a breach and allowed high-pressure helium to escape into the low-pressure propellant tank, causing the failure. The Dragon software issue was also fixed in addition to an analysis of the entire program in order to ensure proper abort mechanisms are in place for future rockets and their payload.[85]

In early September 2016, a Falcon 9 exploded during a propellant fill operation for a standard pre-launch static fire test.[86][87] The payload, the Amos-6 communications satellite valued at US$200 million, was destroyed.[88] Musk described the event as the "most difficult and complex failure" in SpaceX's history; SpaceX reviewed nearly 3,000 channels of telemetry and video data covering a period of 35–55 milliseconds for the postmortem.[89] Musk reported that the explosion was caused by the liquid oxygen that is used as propellant turning so cold that it solidified and ignited with carbon composite helium vessels.[90] Though not considered an unsuccessful flight, the rocket explosion sent the company into a four-month launch hiatus while it worked out what went wrong. SpaceX returned to flight in January 2017.[91]

On 28 June 2019, SpaceX announced that it had lost contact with three of the 60 satellites making up the Starlink mega constellation. The dysfunctional satellites' orbits are expected to slowly decay until they disintegrate in the atmosphere.[92] However, the rate of failure for satellites in mega-constellations consisting of thousands of satellites has raised concerns that these constellations could litter the Earth's lower orbit, with serious detrimental consequences for future space flights.[93]

Ownership, funding, and valuation

In August 2008, SpaceX accepted a US$20 million investment from Founders Fund.[94] In early 2012, approximately two-thirds of the company stock was owned by its founder [95] and his 70 million shares were then estimated to be worth US$875 million on private markets,[96] which roughly valued SpaceX at US$1.3 billion as of February 2012.[97] After the COTS 2+ flight in May 2012, the company private equity valuation nearly doubled to US$2.4 billion or US$20/share.[98][99]

By May 2012, — ten years after founding—SpaceX had operated on total funding of approximately US$1 billion over its first decade of operation. Of this, private equity provided approximately US$200 million with Musk investing approximately US$100 million and other investors (Founders Fund, Draper Fisher Jurvetson, etc.) having put in about US$100 million.[100] The remainder had come from progress payments on long-term launch contracts and development contracts, as working capital, not equity.

In January 2015, SpaceX raised US$1 billion in funding from Google and Fidelity, in exchange for 8.33% of the company, establishing the company valuation at approximately US$12 billion. Google and Fidelity joined prior investors Draper Fisher Jurvetson, Founders Fund, Valor Equity Partners and Capricorn Investment Group.[101][102] In July 2017, the Company raised US$350 million for a valuation of US$21 billion.[103]

Congressional testimony by SpaceX in 2017 suggested that the NASA Space Act Agreement process of "setting only a high-level requirement for cargo transport to the space station [while] leaving the details to industry" had allowed SpaceX to design and develop the Falcon 9 rocket on its own at a substantially lower cost. According to NASA's own independently verified numbers, SpaceX's total development cost for both the Falcon 1 and Falcon 9 rockets was estimated at approximately US$390 million. In 2011, NASA estimated that it would have cost the agency about US$4 billion to develop a rocket like the Falcon 9 booster based upon NASA's traditional contracting processes, about ten times more.[104]

By March 2018, SpaceX had contracts for 100 launch missions, and each of those contracts provides down payments at contract signing, plus many are paying progress payments as launch vehicle components are built in advance of mission launch, driven in part by US accounting rules for recognizing long-term revenue.[42]

SpaceX raised a total of US$1.33 billion of capital across three funding rounds in 2019.[106]

In April 2019, the Wall Street Journal reported the company was raising US$500 million in funding.[107] In May 2019, SpaceNews reported SpaceX "raised US$1.022 billion" the day after SpaceX launched 60 satellites towards their 12,000 satellite plan named Starlink broadband constellation.[108][109] By 31 May 2019, the valuation of SpaceX had risen to US$33.3 billion.[110] In June 2019, SpaceX began a raise of US$300 million, most of it from the Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan, which then had some US$191 billion in assets under management.[111]

As of February 2020, SpaceX was raising an additional amount of about US$250 million through equity stock offerings. In May 2020, its valuation reached US$36 billion.[112] On 19 August 2020, after having had finished a US$1.9 billion funding round, one of the largest single fundraising pushes by any privately held company, SpaceX's valuation increased to US$46 billion.[113][114]

Hardware

Launch vehicles

.jpg.webp)

Falcon 1 was a small rocket capable of placing several hundred kilograms into low Earth orbit.[115] It functioned as an early test-bed for developing concepts and components for the larger Falcon 9.[115] Falcon 1 attempted five flights between 2006 and 2009. With Falcon 1, when Musk announced his plans for it before a subcommittee in the Senate in 2004, he discussed that Falcon 1 would be the "worlds only semi-reusable orbital rocket" apart from the Space Shuttle.[116] On 28 September 2008, on its fourth attempt, the Falcon 1 successfully reached orbit, becoming the first privately funded, liquid-fueled rocket to do so.[117]

Falcon 9 is an NSSL-certified Medium-lift launch vehicle capable of delivering up to 22,800 kilograms (50,265 lb) to orbit, competing with the Delta IV and the Atlas V rockets, as well as other launch providers around the world. It has nine Merlin engines in its first stage.[118] The Falcon 9 v1.0 rocket successfully reached orbit on its first attempt on 4 June 2010. Its third flight, COTS Demo Flight 2, launched on 22 May 2012, and was the first commercial spacecraft to reach and dock with the International Space Station (ISS).[119] The vehicle was upgraded to Falcon 9 v1.1 in 2013, Falcon 9 Full Thrust in 2015, and finally to Falcon 9 Block 5 in 2018. As of 20 January 2021, the Falcon 9 and Heavy family has flown 106 of 108 successful missions with one failure, one partial success, and one vehicle destroyed during a routine test several days prior to a scheduled launch.

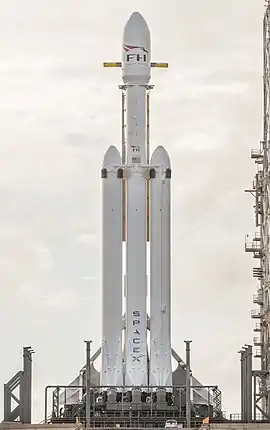

Falcon Heavy is an (NSSL) National Security Space Launch-certified Heavy-lift launch vehicle capable of delivering up to 63,800 kg (140,700 lb) to Low Earth orbit (LEO) or 26,700 kg (58,900 lb) to Geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). It uses three slightly modified Falcon 9 first stage cores with a total of 27 Merlin 1D engines.[120][121]

The Falcon Heavy successfully flew its inaugural mission on 6 February 2018, launching Musk's personal Tesla Roadster into heliocentric orbit[122] At the time of its first launch, SpaceX described their Falcon Heavy as "the world's most powerful rocket in operation".[123]

Rocket engines

Since the founding of SpaceX in 2002, the company has developed three families of rocket engines — Merlin and the retired Kestrel for launch vehicle propulsion, and the Draco control thrusters. SpaceX is currently developing one new rocket engine: the Raptor. SpaceX is currently the world's most prolific producer of liquid fuel rocket engines.[124] Merlin is a family of rocket engines developed by SpaceX for use on their launch vehicles. Merlin engines use liquid oxygen (LOX) and RP-1 as propellants in a gas-generator power cycle. The Merlin engine was originally designed for sea recovery and reuse. The injector at the heart of Merlin is of the pintle type that was first used in the Apollo Program for the lunar module landing engine. Propellants are fed via a single shaft, dual impeller turbo-pump. Kestrel is a LOX/RP-1 pressure-fed rocket engine and was used as the Falcon 1 rocket's second stage main engine. It is built around the same pintle architecture as SpaceX's Merlin engine but does not have a turbo-pump, and is fed only by tank pressure. Its nozzle is ablatively cooled in the chamber and throat, is also radiatively cooled, and is fabricated from a high strength niobium alloy. Both names for the Merlin and Kestrel engines are derived from species of North American falcons: the American kestrel and the merlin.[125]

Draco engines are hypergolic liquid-propellant rocket engines that utilize monomethyl hydrazine fuel and nitrogen tetroxide oxidizer. Each Draco thruster generates 400 N (90 lbf) of thrust.[126] They are used as reaction control system (RCS) thrusters on the Dragon spacecraft.[127]

SuperDraco engines are a much more powerful version of the Draco thrusters, which were initially meant to be used as landing and launch escape system engines on Dragon 2. The concept of using retro-rockets for landing was scrapped in 2017 when it was decided to perform a traditional parachute descent and splashdown at sea.[128] Raptor is a new family of methane-fueled full-flow staged combustion cycle engines to be used in its future Starship launch system.[129] Development versions were test-fired in late 2016.[130] On 3 April 2019, SpaceX conducted a successful static fire test in Texas on its Starhopper vehicle, which ignited the engine while the vehicle remained tethered to the ground.[131] On 25 July 2019, SpaceX conducted a successful test hop of 20 meters of its Starhopper.[132] On 28 August 2019, Starhopper conducted a successful test hop of 150 meters.[133]

Dragon spacecraft

.jpg.webp)

In 2005, SpaceX announced plans to pursue a human-rated commercial space program through the end of the decade.[134] The Dragon is a conventional blunt-cone ballistic capsule that is capable of carrying cargo or up to seven astronauts into orbit and beyond.[135] In 2006, NASA announced that the company was one of two selected to provide crew and cargo resupply demonstration contracts to the ISS under the COTS program.[136] SpaceX demonstrated cargo resupply and eventually crew transportation services using the Dragon.[119] The first flight of a Dragon structural test article took place in June 2010, from Launch Complex 40 (SLC-40) at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS) during the maiden flight of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle; the mock-up Dragon lacked avionics, heat shield, and other key elements normally required of a fully operational spacecraft but contained all the necessary characteristics to validate the flight performance of the launch vehicle.[137] An operational Dragon spacecraft was launched in December 2010 aboard COTS Demo Flight 1, the Falcon 9's second flight, and safely returned to Earth after two orbits, completing all its mission objectives.[138] In 2012, Dragon became the first commercial spacecraft to deliver cargo to the International Space Station,[119] and has since been conducting regular resupply services to the ISS.[139]

In April 2011, NASA issued a US$75 million contract, as part of its second-round commercial crew development (CCDev) program, for SpaceX to develop an integrated launch escape system for Dragon in preparation for human-rating it as a crew transport vehicle to the ISS.[140] In August 2012, NASA awarded SpaceX a firm, fixed-price Space Act Agreement (SAA) with the objective of producing a detailed design of the entire crew transportation system. This contract includes numerous key technical and certification milestones, an uncrewed flight test, a crewed flight test, and six operational missions following system certification.[141] The fully autonomous Crew Dragon spacecraft is expected to be one of the safest crewed spacecraft systems. Reusable in nature, the Crew Dragon will offer savings to NASA.[141] SpaceX conducted a test of an empty Crew Dragon to ISS in early 2019, and later in the year, they plan to launch a crewed Dragon which will send U.S. astronauts to the ISS for the first time since the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011.[142][143] In February 2017, SpaceX announced that two would-be space tourists had put down "significant deposits" for a mission which would see the two tourists fly on board a Dragon capsule around the Moon and back again.

In addition to SpaceX's privately funded plans for an eventual Mars mission, NASA Ames Research Center had developed a concept called Red Dragon: a low-cost Mars mission that would use Falcon Heavy as the launch vehicle and trans-Martian injection vehicle, and the Dragon capsule to enter the Martian atmosphere. The concept was originally envisioned for launch in 2018 as a NASA Discovery mission, then alternatively for 2022.[144] The objectives of the mission would be to return the samples from Mars to Earth at a fraction of the cost of the NASA own return-sample mission now projected at US$6 billion.[144][145] In September 2017, Elon Musk released first prototype images of their spacesuits to be used in future missions. The suit is in the testing phase and it is designed to cope with 2 atm (200 kPa; 29 psi) pressure in vacuum.[146][147] The Crew Dragon spacecraft was first sent to space on 2 March 2019.

On 27 March 2020, SpaceX revealed the Dragon XL resupply spacecraft to carry pressurized and unpressurized cargo, experiments and other supplies to NASA's planned Gateway under a Gateway Logistics Services (GLS) contract.[148] The equipment delivered by Dragon XL missions could include sample collection materials, spacesuits and other items astronauts may need on the Gateway and on the surface of the Moon, according to NASA. It will launch on SpaceX Falcon Heavy rockets from pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The Dragon XL will stay at the Gateway for six to 12 months at a time, when research payloads inside and outside the cargo vessel could be operated remotely, even when crews are not present.[149] Its payload capacity is expected to be more than 5 t (5,000 kg; 11,000 lb) to lunar orbit.[150]

On 7 December 2020, SpaceX launched new cargo Dragon to Space Station for 100th successful Falcon 9 flight. This is the first launch for this redesigned cargo Dragon, and also the first mission for SpaceX's new series of CRS missions under a renewed contract with NASA. It is carrying 6,400 lb (2,900 kg) of both supplies for the Space Station and its crew, as well as experimental supplies and equipments for the research being done on the Station. This version of Dragon can carry 20% more than the last cargo spacecraft from SpaceX, and it also has twice the number of powered lockers for climate controlled transportation of experimental material.[151]

Reusable launch system

.jpg.webp)

SpaceX's reusable launcher program was publicly announced in 2011 and the design phase was completed in February 2012. The system returns the first stage of a Falcon 9 rocket to a predetermined landing site using only its own propulsion systems.[152]

SpaceX's active test program began in late 2012 with testing low-altitude, low-speed aspects of the landing technology. The prototypes of Falcon 9 performed vertical takeoffs and landings.

High-velocity, high-altitude aspects of the booster atmospheric return technology began testing in late 2013 and have continued through 2018, with a 98% success rate to date. As a result of Elon Musk's goal of crafting more cost-effective launch vehicles, SpaceX conceived a method to reuse the first stage of their primary rocket, the Falcon 9,[153] by attempting propulsive vertical landings on solid surfaces. Once the company determined that soft landings were feasible by touching down over the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, they began landing attempts on a solid platform. SpaceX first achieved a successful landing and recovery of a first stage in December 2015,[154] and in April 2016, the first stage booster first successfully landed on the autonomous spaceport drone ship (ASDS) Of Course I Still Love You.[155][156]

SpaceX continues to carry out first stage landings on every orbital launch that fuel margins allow. By October 2016, following the successful landings, SpaceX indicated they were offering their customers a 10% price discount if they choose to fly their payload on a reused Falcon 9 first stage.[157] On 30 March 2017, SpaceX launched a "flight-proven" Falcon 9 for the SES-10 satellite. This was the first time a re-launch of a payload-carrying orbital rocket went back to space.[73][158] The first stage was recovered and landed on the ASDS Of Course I Still Love You in the Atlantic Ocean, also making it the first landing of a reused orbital class rocket. Elon Musk called the achievement an "incredible milestone in the history of space".[159][160]

Autonomous spaceport drone ship

SpaceX leased and modified several barges to sit out at sea as a target for the returning first stage, converting them to autonomous spaceport drone ships (ASDS). These ships are used as landing platforms for the Falcon 9 launch vehicle when propellent margins do not permit a return to launch site (RTLS) flight.

The autonomous spaceport drone ships are named after giant starships from the Culture series stories by science fiction author Iain M. Banks.[161]

Floating launch platforms

SpaceX's floating launch platforms are modified oil rigs now under construction to use in the 2020s to provide a sea launch option for their second-generation launch vehicle: the heavy-lift Starship system, consisting of the Super Heavy booster and Starship second stage.

SpaceX has purchased two deepwater oil rigs, for Starship launches, and both platforms are undergoing refit for their new role.

Starship

SpaceX is developing a super-heavy lift launch system, Starship. Starship is a fully reusable second stage and space vehicle intended to replace all of the company's existing launch vehicle hardware by the early 2020s; plus ground infrastructure for rapid launch and relaunch and zero-gravity propellant transfer technology in low Earth orbit (LEO).

SpaceX initially envisioned a 12-meter-diameter ITS concept in 2016 which was solely aimed at Mars transit and other interplanetary uses. In 2017, SpaceX articulated a smaller 9-meter-diameter BFR to replace all of SpaceX launch service provider capabilities — Earth-orbit, lunar-orbit, interplanetary missions, and potentially, even intercontinental passenger transport on Earth — but do so on a fully reusable set of vehicles with a markedly lower cost structure.[162] A large portion of the components on Starship are made of 301 stainless steel, with some being manufactured from 304L stainless steel.[163] Private passenger Yusaku Maezawa has contracted to fly around the Moon in Starship in 2023.[164][165][166]

Musk's long-term vision for the company is the development of technology and resources suitable for human colonization on Mars. He has expressed his interest in someday traveling to the planet, stating "I'd like to die on Mars, just not on impact".[167] A rocket every two years or so could provide a base for the people arriving in 2025 after a launch in 2024.[168][169] According to Steve Jurvetson, Musk believes that by 2035 at the latest, there will be thousands of rockets flying a million people to Mars, in order to enable a self-sustaining human colony.[170]

Other projects

In January 2015, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk announced the development of a new satellite constellation, called Starlink, to provide global broadband internet service. In June 2015, the company asked the federal government for permission to begin testing for a project that aims to build a constellation of 4,425 satellites capable of beaming the Internet to the entire globe, including remote regions that currently do not have Internet access.[171][172] The Internet service would use a constellation of 4,425 cross-linked communications satellites in 1,100 km orbits. Owned and operated by SpaceX, the goal of the business is to increase profitability and cash flow, to allow SpaceX to build its Mars colony.[173] Development began in 2015, initial prototype test-flight satellites were launched on the SpaceX Paz satellite mission in 2017. Initial operation of the constellation could begin as early as 2020. As of March 2017, SpaceX filed with the U.S. regulatory authorities plans to field a constellation of an additional 7,518 "V-band satellites in non-geosynchronous orbits to provide communications services" in an electromagnetic spectrum that had not previously been "heavily employed for commercial communications services". Called the "V-band low-Earth-orbit (VLEO) constellation", it would consist of "7,518 satellites to follow the [earlier] proposed 4,425 satellites that would function in Ka- and Ku-band".[174]

In February 2019, SpaceX formed a sibling company, SpaceX Services, Inc., to license the manufacture and deployment of up to 1,000,000 fixed satellite Earth stations that will communicate with its Starlink system.[175] In May 2019, SpaceX launched the first batch of 60 satellites aboard a Falcon 9 from Cape Canaveral, Florida.[176] As of 25 November 2020, SpaceX has launched 955 Starlink satellites. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) awarded SpaceX with nearly US$900 million worth of federal subsidies to support rural broadband customers through the company's Starlink satellite internet network. SpaceX won subsidies to bring service to customers in 35 U.S. states.[177]

In June 2015, SpaceX announced that they would sponsor a Hyperloop competition, and would build a 1.6 km (0.99 mi) long subscale test track near SpaceX's headquarters for the competitive events.[178][179] The first competitive event was held at the track in January 2017, the second in August 2017 and the third in December 2018.[180][181][182]

Facilities

SpaceX is headquartered in Hawthorne, California, which also serves as its primary manufacturing plant. The company operates a research and major operation in Redmond, Washington, owns a test site in Texas and operates three launch sites, with another under development. SpaceX also operates regional offices in Texas, Virginia, and Washington, D.C.[42]

Headquarters, manufacturing, and refurbishment facilities

.jpg.webp)

SpaceX Headquarters is located in the Los Angeles suburb of Hawthorne, California. The large three-story facility, originally built by Northrop Corporation to build Boeing 747 fuselages,[183] houses SpaceX's office space, mission control, and, as of 2018, all vehicle manufacturing. In March 2018, SpaceX indicated that it would manufacture its next-generation, 9 m (30 ft)-diameter launch vehicle, the Starship at a new facility on the Los Angeles waterfront in the San Pedro area. The company had leased an 18 acres (73,000 m2) site near Berth 240 in the Los Angeles, however in January 2019 the lease was canceled and the construction of Starship moved to a new site in South Texas.[184][185][186]

The area has one of the largest concentrations of aerospace headquarters, facilities, and/or subsidiaries in the U.S., including Boeing/McDonnell Douglas main satellite building campuses, Aerospace Corp., Raytheon, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Air Force Space Command's Space and Missile Systems Center at Los Angeles Air Force Base, Lockheed Martin, BAE Systems, Northrop Grumman, and AECOM, etc., with a large pool of aerospace engineers and recent college engineering graduates.[183]

SpaceX utilizes a high degree of vertical integration in the production of its rockets and rocket engines.[33] SpaceX builds its rocket engines, rocket stages, spacecraft, principal avionics and all software in-house in their Hawthorne facility, which is unusual for the aerospace industry. Nevertheless, SpaceX still has over 3,000 suppliers with some 1,100 of those delivering to SpaceX nearly weekly.[187]

In June 2017, SpaceX announced they would construct a facility on 0.88 ha (2.17 acres) in Port Canaveral, Florida for refurbishment and storage of previously-flown Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy booster cores.[188]

Development and test facilities

SpaceX operates its first Rocket Development and Test Facility in McGregor, Texas. All SpaceX rocket engines are tested on rocket test stands, and low-altitude VTVL flight testing of the Falcon 9 Grasshopper v1.0 and F9R Dev1 test vehicles in 2013–2014 were carried out at McGregor. 2019 low-altitude VTVL testing of the much larger 9 m (30 ft)-diameter "Starhopper" is planned to occur at the SpaceX South Texas launch site near Brownsville, Texas, which is currently under construction.[189][190][191] On 23 January 2019, strong winds at the Texas test launch site blew over the nose cone over the first test article rocket, causing delays that will take weeks to repair according to SpaceX representatives.[192] In the event, SpaceX decided to forego building another nose cone for the first test article, because at the low velocities planned for that rocket, it was unnecessary.

The company purchased the McGregor facilities from Beal Aerospace, where it refitted the largest test stand for Falcon 9 engine testing. SpaceX has made a number of improvements to the facility since purchase and has also extended the acreage by purchasing several pieces of adjacent farmland. In 2011, the company announced plans to upgrade the facility for launch testing a VTVL rocket,[54] and then constructed a half-acre concrete launch facility in 2012 to support the Grasshopper test flight program.[55] As of October 2012, the McGregor facility had seven test stands that are operated "18 hours a day, six days a week"[193] and is building more test stands because production is ramping up and the company has a large manifest in the next several years.

In addition to routine testing, Dragon capsules (following recovery after an orbital mission), are shipped to McGregor for de-fueling, cleanup, and refurbishment for reuse in future missions.

Launch facilities

.jpg.webp)

SpaceX currently operates three orbital launch sites, at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Vandenberg Air Force Base, and Kennedy Space Center, and is under construction on a fourth in Brownsville, Texas. SpaceX has indicated that they see a niche for each of the four orbital facilities and that they have sufficient launch business to fill each pad.[194] The Vandenberg launch site enables highly inclined orbits (66–145°), while Cape Canaveral enables orbits of medium inclination, up to 51.6°.[195] Before it was retired, all Falcon 1 launches took place at the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site on Omelek Island.

Cape Canaveral Space Force Station

Cape Canaveral Space Launch Complex 40 (SLC-40) is used for Falcon 9 launches to low Earth and geostationary orbits. SLC-40 is not capable of supporting Falcon Heavy launches. As part of SpaceX's booster reusability program, the former Launch Complex 13 at Cape Canaveral, now renamed Landing Zone 1, has been designated for use for Falcon 9 first-stage booster landings.

.jpg.webp)

Vandenberg Air Force Base

Vandenberg Space Launch Complex 4 (SLC-4E) is used for payloads to polar orbits. The Vandenberg site can launch both Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy,[196] but cannot launch to low inclination orbits. The neighboring SLC-4W has been converted to Landing Zone 4, where SpaceX has successfully landed three Falcon 9 first-stage boosters, the first in October 2018.[197]

Kennedy Space Center

On 14 April 2014, SpaceX signed a 20-year lease for Launch Pad 39A.[198] The pad was subsequently modified to support Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches. SpaceX has launched 13 Falcon 9 missions from Launch Pad 39A, the latest of which was launched on 15 November 2020.[199] SpaceX launched its first crewed mission to the ISS from Launch Pad 39A on 30 May 2020.[200]

Brownsville

In August 2014, SpaceX announced they would be building a commercial-only launch facility at Brownsville, Texas.[201][202] The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) released a draft Environmental Impact Statement for the proposed Texas facility in April 2013, and "found that 'no impacts would occur' that would force the Federal Aviation Administration to deny SpaceX a permit for rocket operations",[203] and issued the permit in July 2014.[204] SpaceX started construction on the new launch facility in 2014 with production ramping up in the latter half of 2015,[205] with the first suborbital launches from the facility in 2019.[189][190][206] Real estate packages at the location have been named by SpaceX with names based on the theme "Mars Crossing".[207][208]

Satellite prototyping facility

In January 2015, SpaceX announced it would be entering the satellite production business and global satellite internet business. The first satellite facility is a 30,000 sq ft (2,800 m2) office building located in Redmond, Washington. As of January 2017, a second facility in Redmond was acquired with 40,625 sq ft (3,774.2 m2) and has become a research and development laboratory for the satellites.[209] In July 2016, SpaceX acquired an additional 8,000 sq ft (740 m2) creative space in Irvine, California (Orange County) to focus on satellite communications.[210][211]

Launch contracts

SpaceX won demonstration and actual supply contracts from NASA for the International Space Station (ISS) with technology the company developed. SpaceX is also certified for U.S. military launches of Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle-class (EELV) payloads. With approximately 30 missions on the manifest for 2018 alone, SpaceX represents over US$12 billion under contract.[42]

SpaceX along with Virgin Galactic were among the first to have a contract with Spaceport America in New Mexico, the first and only full-scale public commercial spaceport in the United States. Among the tests conducted at the spaceport was the Grasshopper, they continue to have a smaller contract with the spaceport for potential future use, alongside their own private SpaceX South Texas Launch Site to the southwest.[212]

COTS

In 2006, NASA announced that SpaceX had won a NASA Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) Phase 1 contract to demonstrate cargo delivery to the International Space Station (ISS), with a possible contract option for crew transport.[213][214] This contract, designed by NASA to provide "seed money" through Space Act Agreements for developing new capabilities, NASA paid SpaceX US$396 million to develop the cargo configuration of the Dragon spacecraft, while SpaceX self-invested more than US$500 million to develop the Falcon 9 launch vehicle.[215] These Space Act Agreements have been shown to have saved NASA millions of dollars in development costs, making rocket development ~4–10 times cheaper than if produced by NASA alone.[104]

In December 2010, the launch of the SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 1 mission, SpaceX became the first private company to successfully launch, orbit and recover a spacecraft.[216] Dragon was successfully deployed into orbit, circled the Earth twice, and then made a controlled re-entry burn for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. With Dragon's safe recovery, SpaceX became the first private company to launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft; prior to this mission, only government agencies had been able to recover orbital spacecraft.

SpaceX COTS Demo Flight 2 launched in May 2012, in which Dragon successfully berthed with the ISS, marking the first time that a private spacecraft had accomplished this feat.[217][218]

Commercial cargo

Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) are a series of contracts awarded by NASA from 2008 to 2016 for delivery of cargo and supplies to the ISS on commercially operated spacecraft. The first CRS contracts were signed in 2008 and awarded US$1.6 billion to SpaceX for 12 cargo transport missions, covering deliveries to 2016.[219] SpaceX CRS-1, the first of the 12 planned resupply missions, launched in October 2012, achieved orbit, berthed and remained on station for 20 days, before re-entering the atmosphere and splashing down in the Pacific Ocean.[220] CRS missions have flown approximately twice a year to the ISS since then. In 2015, NASA extended the Phase 1 contracts by ordering an additional three resupply flights from SpaceX, for a total of 15 cargo transport.[221][222] After further extensions late in 2015, SpaceX is currently scheduled to fly a total of 20 resupply missions.[223] A second phase of contracts (known as CRS-2) were solicited and proposed in 2014. They were awarded in January 2016, for cargo transport flights beginning in 2019 and expected to last through 2024. SpaceX will be using Dragon XL spacecraft on Falcon Heavy rockets to send supplies to NASA's Gateway space station.[224]

Commercial crew

.jpg.webp)

The Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program intends to develop commercially operated spacecraft that are capable of delivering astronauts to the ISS. SpaceX did not win a Space Act Agreement in the first round (CCDev 1), but during the second round (CCDev 2), NASA awarded SpaceX with a contract worth US$75 million to further develop their launch escape system, test a crew accommodations mock-up, and to further progress their Falcon/Dragon crew transportation design.[225][226][227] The CCDev program later became Commercial Crew Integrated Capability (CCiCap), and in August 2012, NASA announced that SpaceX had been awarded US$440 million to continue development and testing of its Dragon 2 spacecraft.[228][229]

In September 2014, NASA chose SpaceX and Boeing as the two companies that will be funded to develop systems to transport U.S. crews to and from the ISS. SpaceX won US$2.6 billion to complete and certify Dragon 2 by 2017. The contracts include at least one crewed flight test with at least one NASA astronaut aboard. Once Crew Dragon achieves NASA certification, the contract requires SpaceX to conduct at least two, and as many as six, crewed missions to the space station.[230] In early 2017, SpaceX was awarded four additional crewed missions to the ISS from NASA to shuttle astronauts back and forth.[231] In early 2019, SpaceX successfully conducted a test flight of Crew Dragon, which it docked (instead of Dragon 1's method of berthing using Canadarm2) and then splashdowned in the Atlantic Ocean.

Progress

On 16 September 2014, NASA selected SpaceX's Falcon 9 launch vehicle and Dragon spacecraft to fly American astronauts to the International Space Station under the Commercial Crew Program.[232]

On 6 May 2015, just after 09:00 Eastern Time, SpaceX completed the first key flight test of its Crew Dragon spacecraft, a vehicle designed to carry astronauts to and from space. The successful Pad Abort Test was the first flight test of SpaceX's revolutionary launch abort system, and the data captured here will be critical in preparing Crew Dragon for its first human missions.[233]

On 3 August 2018, NASA announced the first four astronauts who will launch aboard Crew Dragon to the International Space Station. Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley will be the first two NASA astronauts to fly in the Dragon spacecraft.[234]

On 2 March 2019, the Crew Dragon Demo-1 launched without crew on board. This mission was intended to demonstrate SpaceX's capabilities to safely and reliably fly astronauts to and from the International Space Station.[235]

On 3 March 2019, Crew Dragon docked with the ISS at 03:02 PST, becoming the first American spacecraft to autonomously dock with the orbiting laboratory.[236]

On 8 March 2019, Crew Dragon splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean at 05:45 PST, completing the spacecraft's first mission to the International Space Station.[237]

On 19 January 2020, Crew Dragon test capsule was launched on a suborbital trajectory to conduct an Crew Dragon In-Flight Abort Test in the troposphere at transonic velocities, at max Q, where the vehicle experiences maximum aerodynamic pressure. The Crew Dragon splashed down at 15:38 UTC just off the Florida coast in the Atlantic Ocean.[199]

On 30 May 2020, the Crew Dragon Demo-2 mission was launched to the International Space Station with American astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley. This was the first time a crewed vehicle had launched from the U.S. since 2011. This was also the first commercial crewed ISS delivery.[238]

On 16 November 2020, the SpaceX Crew-1 mission was successfully launched to the International Space Station with NASA astronauts Michael Hopkins, Victor Glover and Shannon Walker along with JAXA astronaut Soichi Noguchi,[239] all members of the Expedition 64 crew.[240]

National defense

In 2005, SpaceX announced that it had been awarded an Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contract, allowing the United States Air Force to purchase up to US$100 million worth of launches from the company.[241] In April 2008, NASA announced that it had awarded an IDIQ Launch Services contract to SpaceX for up to US$1 billion, depending on the number of missions awarded. The contract covers launch services ordered by June 2010, for launches through December 2012.[242] Musk stated in the same 2008 announcement that SpaceX has sold 14 contracts for flights on the various Falcon vehicles.[242] In December 2012, SpaceX announced its first two launch contracts with the United States Department of Defense (DoD). The United States Air Force Space and Missile Systems Center awarded SpaceX two EELV-class missions: Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) and Space Test Program 2 (STP-2). DSCOVR was launched on a Falcon 9 launch vehicle in 2015, while STP-2 was launched on a Falcon Heavy on 25 June 2019.[243]

In May 2015, the United States Air Force announced that the Falcon 9 v1.1 was certified for National Security Space Launch (NSSL), which allows SpaceX to contract launch services to the Air Force for any payloads classified under national security.[244] This broke the monopoly held since 2006 by United Launch Alliance (ULA) over the U.S. Air Force launches of classified payloads.[245]

In April 2016, the U.S. Air Force awarded the first such national security launch, an US$82.7 million contract to SpaceX to launch the 2nd GPS 3 satellite launched on 22 August 2019; this estimated cost was approximately 40% less than the estimated cost for similar previous missions.[246][247][248] Prior to this, United Launch Alliance was the only provider certified to launch national security payloads.[249][250] ULA did not submit a bid for the May 2018 launch.[251][252]

In 2016, the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) said it had purchased launches from SpaceX - the first (for NROL-76) took place on 1 May 2017.[253]

In March 2017, SpaceX won (versus ULA) with a bid of US$96.5 million for the 3rd GPS 3 launch (launched on 20 June 2020).[254]

In March 2018, SpaceX secured an additional US$290 million contract from the U.S. Air Force to launch three next-generation (#4-6) GPS satellites, known as GPS III. The first of these launches is expected to take place in March 2020.[255]

In February 2019, SpaceX secured a US$297 million contract from the U.S. Air Force to launch three national security missions, including AFSPC-44, NROL-87, and NROL-85, all slated to launch no earlier than FY 2021.[256]

On 7 August 2020, the U.S. Space Force awarded its National Security Space Launch (NSSL) contracts for the following 5–7 years; SpaceX won a contract for US$316 million for one launch while ULA received a contract for US$337 million to perform two launches. In addition, SpaceX will handle 40% of the U.S. militaries satellite launch requirements over the 5–7 years while ULA will handle 60%, each company is required to act as backup launch provider for the other.[257]

Space Adventures

In February 2020, Space Adventures announced plans to fly private citizens into orbit on Crew Dragon.[258] The Crew Dragon vehicle would launch from LC-39A with up to four tourists on board, and spend up to five days in a low Earth orbit with an apogee of over 1,000 km (620 mi).[259]

Kazakhstan

SpaceX won a contract to launch two Kazakhstani satellites aboard the Falcon 9 launch rocket on a rideshare with other satellites. The launch took place at Vandenberg Air Force Base on 3 December 2018, with KazSaySat and KazistiSat, included in a payload totaling 64 miniature and small satellites.[260][261][262] According to the Kazakh Defence and Aerospace Ministry, the launch from SpaceX cost the country US$1.3 million.[263]

Armenian protests against Türksat 5A satellite launch

The Armenian community of Los Angeles County, California staged protests at SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne on 29 October 2020 [264] and 30 October 2020,[265] demanding the cancellation of Türksat 5A satellite launch on a Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida launched on 8 January 2021. This was preceded by a mass email campaign to SpaceX staff and members of the media by concerned Armenians around the world, asking the company to cancel the launch contract with the Turkish government.[266] The Armenians claimed that the satellite could be used by the Turkish government for military purposes, in view of Turkey's current provision of unmanned aerial vehicles to Azerbaijan in its armed conflict with Armenia involving the Nagorno-Karabakh region.[267]

Launch market competition and pricing pressure

SpaceX's low launch prices, especially for communication satellites flying to geostationary (GTO) orbit, have resulted in market pressure on its competitors to lower their own prices.[33] Prior to 2013, the openly competed comsat launch market had been dominated by Arianespace (flying Ariane 5) and International Launch Services (flying Proton).[268] With a published price of US$56.5 million per launch to low Earth orbit, "Falcon 9 rockets [were] already the cheapest in the industry. Reusable Falcon 9s could drop the price by an order of magnitude, sparking more space-based enterprise, which in turn would drop the cost of access to space still further through economies of scale".[269] SpaceX has publicly indicated that if they are successful with developing the reusable technology, launch prices in the US$5 to 7 million range for the reusable Falcon 9 are possible.[270]

In 2014, SpaceX had won nine contracts out of 20 that were openly competed worldwide in 2014 at commercial launch service providers.[271] Space media reported that SpaceX had "already begun to take market share" from Arianespace.[272] Arianespace has requested that European governments provide additional subsidies to face the competition from SpaceX.[273][274] European satellite operators are pushing the European Space Agency (ESA) to reduce Ariane 5 and the future Ariane 6 rocket launch prices as a result of competition from SpaceX. According to one Arianespace managing director in 2015, it was clear that "a very significant challenge [was] coming from SpaceX ... Therefore things have to change ... and the whole European industry is being restructured, consolidated, rationalized and streamlined".[275] Jean Botti, director of innovation for Airbus (which makes the Ariane 5) warned that "those who don't take Elon Musk seriously will have a lot to worry about".[276] In 2014, no commercial launches were booked to fly on the Russian Proton rocket.[271]

Also in 2014, SpaceX capabilities and pricing began to affect the market for launch of U.S. military payloads. For nearly a decade the large U.S. launch provider United Launch Alliance (ULA) had faced no competition for military launches.[277] Without this competition, launch costs by the U.S. provider rose to over US$400 million.[278] The ULA monopoly ended when SpaceX began to compete for national security launches. At a side-by-side comparison, SpaceX's launch costs for commercial missions are considerably lower at US$62 million.[279]

In 2015, anticipating a slump in domestic, military, and spy launches, ULA stated that it would go out of business unless it won commercial satellite launch orders.[280] To that end, ULA announced a major restructuring of processes and workforce in order to decrease launch costs by half.[281][282]

In 2017, SpaceX had 45% global market share for awarded commercial launch contracts, the estimate for 2018 is about 65% as of July 2018.[283]

On 11 January 2019, SpaceX issued a statement announcing it would lay off 10% of its workforce, in order to help finance the Starship and Starlink projects.[284]

In the first quarter of 2020, SpaceX launched over 61,000 kg (134,000 lb) of payload mass to orbit while all Chinese, European, and Russian launchers placed approximately 21,000 kg (46,000 lb), 16,000 kg (35,000 lb) and 13,000 kg (29,000 lb) in orbit, respectively, with all other launch providers launching approximately 15,000 kg (33,000 lb).[285]

NASA announced its first crewed launch in over a decade using SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule would take place 27 May 2020, from Kennedy Space Center, at Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A), taking astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley to the International Space Station.[286] The launch was postponed due to bad weather.[287] The vehicle launched successfully on 30 May 2020, and successfully docked with the International Space Station on 31 May 2020, at 10:16 Eastern Daylight Time (EDT).[288][289]

On 26 May 2020, the NASA's administrator, Jim Bridenstine, stated that: "Because of the investments that NASA has made into SpaceX we now have, the United States of America now has about 70 percent of the commercial launch market, ... That is a big change from 2012 when we had exactly zero percent".[290]

Board of directors

| Joined Board | Name | Titles |

|---|---|---|

| 2002 [292] | Elon Musk | Founder, Chairman, CEO and CTO of SpaceX; co-founder, CEO and Product Architect of Tesla; former Chairman of Tesla, Inc.; former Chairman of SolarCity [292] |

| 2002 [293] | Kimbal Musk | Board member, Tesla [294] |

| 2009 [295] | Gwynne Shotwell | President and COO of SpaceX [296] |

| 2009 [295] | Luke Nosek | Co-founder, PayPal [297] |

| 2009 [295] | Steve Jurvetson | Co-founder, Future Ventures fund [298] |

| 2010 [299] | Antonio Gracias | CEO and Chairman of the Investment Committee at Valor Equity Partners [300] |

| 2015 [301] | Donald Harrison | President of global partnerships and corporate development, Google [302] |

See also

| A book on this topic is available: Book:SpaceX |

- Blue Origin

- Human mission to Mars

- List of crewed spacecraft

- NewSpace

- Space colonization

- SpaceX Mars transportation infrastructure

References

- "California Business Search (C2414622 - Space Exploration Technologies Corp)". California Secretary of State. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Who is Elon Musk, and what made him big? | Business| Economy and finance news from a German perspective | DW | 27.05.2020". Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Fred Lambert (17 November 2016). "Elon Musk's stake in SpaceX is actually worth more than his Tesla shares". Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Gwynne Shotwell: Executive Profile & Biography". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- W.J. Hennigan (7 June 2013). "How I Made It: SpaceX exec Gwynne Shotwell". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- SpaceX Tour – Texas Test Site. YouTube. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- "SpaceX NASA CRS-6 PressKit" (PDF). 12 April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Podcast: SpaceX COO On Prospects For Starship Launcher Archived June 10, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Aviation Week Irene Klotz, 27 May 2020, accessed 10 June 2020

- Kenneth Chang (27 September 2016). "Elon Musk's Plan: Get Humans to Mars, and Beyond". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "Making Life Multi-planetary". relayto.com. 2018. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- Shontell, Alyson. "Elon Musk Decided To Put Life On Mars Because NASA Wasn't Serious Enough". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Stephen Clark (28 September 2008). "Sweet Success at Last for Falcon 1 Rocket". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Kenneth Chang (25 May 2012). "Space X Capsule Docks at Space Station". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Launch Schedule". Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- "Space Station – off the Earth, for the Earth". Archived from the original on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "SpaceX". SpaceX. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- William Graham (13 April 2015). "SpaceX Falcon 9 launches CRS-6 Dragon en route to ISS". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Matthew Weaver (22 December 2015). ""Welcome back, baby": Elon Musk celebrates SpaceX rocket launch – and landing". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "SpaceX rocket successfully lands on ocean drone platform for third time". The Guardian. 8 April 2016. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Loren Grush (19 May 2016). "SpaceX successfully lands its Falcon 9 rocket on a floating drone ship again". The Verge. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Amos, Jonathan. "Success for SpaceX "re-usable rocket"". bbc.com. BBC News. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Patel, Neel. "SpaceX now operates the world's biggest commercial satellite network". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Lauer, Alex. "SpaceX Is the New King of Commercial Satellites, and It's Just Getting Started". Insidehook. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Chris Gebhardt (29 September 2017). "The Moon, Mars, and around the Earth – Musk updates BFR architecture, plans". Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Musk, Elon (1 March 2018). "Making Life Multi-Planetary". New Space. 6 (1): 2–11. Bibcode:2018NewSp...6....2M. doi:10.1089/space.2018.29013.emu.

- Elon Musk (29 September 2017). Becoming a Multiplanet Species (video). 68th annual meeting of the International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide, Australia: SpaceX. Retrieved 31 December 2017 – via YouTube.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Mars Presentation | 2016". relayto.com. 2018. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018.

- "Elon Musk says moon mission is "dangerous" but SpaceX's first passenger isn't scared". cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Miles O'Brien (1 June 2012). "Elon Musk Unedited". Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- John Carter McKnight (25 September 2001). "Elon Musk, Life to Mars Foundation". Space Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Elon Musk (30 May 2009). "Risky Business". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Elon Musk on dodging a nervous breakdown. YouTube. 20 April 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Andrew Chaikin (January 2012). "Is SpaceX Changing the Rocket Equation?". Air & Space Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Ashlee Vance (14 May 2015). "Elon Musk's space dream almost killed Tesla". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 11 February 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "How Steve Jurvetson Saved Elon Musk". Business Insider. 14 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- "SpaceX". NASA Space Academy at Glenn. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Elon's SpaceX Tour – Engines. YouTube. 11 December 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- SpaceX and Daring to Think Big – Steve Jurvetson. YouTube. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Michael Belfiore (1 September 2009). "Behind the Scenes With the World's Most Ambitious Rocket Makers". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Crosbie, Jackie (28 September 2016). "Elon Musk Explains Why SpaceX Only Hires Americans". Archived from the original on 23 April 2019.

- spacexcmsadmin (27 November 2012). "Company". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Company | SpaceX". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Stephen Clark (24 November 2013). "Sizing up America's place in the global launch industry". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- Hughes, Tim (13 July 2017). "Statement of Tim Hughes Senior Vice President for Global Business and Government Affairs Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 October 2017.

- Chang, Kenneth (30 May 2020). "SpaceX Lifts NASA Astronauts to Orbit, Launching New Era of Spaceflight - The trip to the space station was the first from American soil since 2011 when the space shuttles were retired". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Wattles, Jackie (30 May 2020). "SpaceX Falcon 9 launches two NASA astronauts into the space CNN". CNN. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "SpaceX-NASA Dragon Demo-2 launch: All your questions answered". indianexpress.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Crew Dragon docks with ISS". spacenews.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "SpaceX is launching its first human crew to space Saturday. How coronavirus affected preparations". The Los Angeles Times. 27 May 2020. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Routine Quarantine Helps Astronauts Avoid Illness Before Launch". Space.com. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Space Exploration Technologies Corporation". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- "Elon Musk – Senate Testimony". SpaceX. 5 May 2004. Archived from the original on 30 August 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- AGAINST ALL ODDS - Elon Musk (Motivational Video), archived from the original on 11 June 2020, retrieved 1 June 2020

- Doug Mohney (26 September 2011). "SpaceX Plans to Test Reusable Suborbital VTVL Rocket in Texas". Satellite Spotlight. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Reusable rocket prototype almost ready for first liftoff". Spaceflight Now. 9 July 2012. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Irene Klotz (27 September 2011). "A rocket that lifts off – and lands – on launch pad". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Agenda Item No. 9, City of Hawthorne City Council, Agenda Bill, September 11, 2018, Planning and Community Development Department, City of Hawthorne, Accessed September 13, 2018

- Nelson, Laura J. (21 November 2017). "Elon Musk's tunneling company wants to dig through L.A." latimes.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Elon Musk posted a video of his Boring Company tunnels under L.A., saying people can use them 'in a few months' for free Archived May 11, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Business Insider, 11 May 2018, accessed 20 May 2018

- "Nothing "Boring" About Elon Musk's Newly Revealed Underground Tunnel". cbslocal.com. 11 May 2018. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Copeland, Rob (17 December 2018). "Elon Musk's New Boring Co. Faced Questions Over SpaceX Financial Ties". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

When the Boring Co. was earlier this year spun into its own firm, more than 90% of the equity went to Mr. Musk and the rest to early employees... The Boring Co. has since given some equity to SpaceX as compensation for the help... about 6% of Boring stock, "based on the value of land, time and other resources contributed since the creation of the company".

- "SpaceX has published Elon Musk's presentation about colonizing Mars – here's the full transcript and slides". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Elon Musk revealed a new plan to colonize Mars with giant reusable spaceships – here are the highlights". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Elon Musk Sets Out SpaceX Starship's Ambitious Launch Timeline". The New York Times. 28 September 2019. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

Mr. Musk, however, has a history of overly optimistic predictions. In Guadalajara in 2016, for example, he said the aim was to send the first cargo flight to Mars in 2022 and the first people there two years later. Those dates are unlikely to be met.

- "Huge Mars Colony Eyed by SpaceX Founder". Discovery News. 13 December 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Rory Carroll (17 July 2013). "Elon Musk's mission to Mars". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Douglas Messier (5 February 2014). "Elon Musk Talks ISS Flights, Vladimir Putin and Mars". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Berger, Eric (28 September 2016). "Musk's Mars moment: Audacity, madness, brilliance – or maybe all three". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Foust, Jeff (10 October 2016). "Can Elon Musk get to Mars?". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Boyle, Alan (27 September 2016). "SpaceX's Elon Musk makes the big pitch for his decades-long plan to colonize Mars". GeekWire. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- Eric Ralph (18 August 2020). "SpaceX's 99th Falcon launch checks off new rocket booster reuse record [updated]". Teslarati. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Mir Juned Hussain (12 November 2014). "The Rise and Rise of SpaceX". Yaabot. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Elon Musk's SpaceX makes history by launching a 'flight-proven' rocket". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- "SpaceX, In Another First, Recovers US$6 Million Nose Cone From Reused Falcon 9". Fortune.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- spacexcmsadmin (29 January 2016). "Zuma mission". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Burghardt, Thomas (25 July 2019). "Starhopper successfully conducts debut Boca Chica Hop". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- O'Callaghan, Jonathan (31 July 2019). "The wild physics of Elon Musk's methane-guzzling super-rocket". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- "SpaceX Launches". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "SpaceX's 1st Crew Dragon with astronauts docks at space station in historic rendezvous". Space.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Hennessy, Paul (25 January 2021). "SpaceX launches record number of spacecraft in cosmic rideshare program". NBC News. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Stephen Clark (20 July 2015). "Support strut probable cause of Falcon 9 failure". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "CRS-7 Investigation Update". SpaceX. 20 July 2015. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "NASA Independent Review Team [IRT] SpaceX CRS-7 Accident Investigation Report Public Summary" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018. "... the key technical finding by the IRT with regard to this failure was that it was due to a design error: SpaceX chose to use an industrial grade (as opposed to aerospace grade) 17-4 PH SS (precipitation-hardening stainless steel) cast part (the "Rod End") in a critical load path under cryogenic conditions and strenuous flight environments. The implementation was done without adequate screening or testing of the industrial grade part, without regard to the manufacturer's recommendations for a 4:1 factor of safety when using their industrial grade part in an application, and without proper modeling or adequate load testing of the part under predicted flight conditions. This design error is directly related to the Falcon 9 CRS-7 launch failure as a "credible" cause..."

- Samantha Masunaga and Melody Petersen (2 September 2016). "SpaceX rocket exploded in an instant. Figuring out why involves a mountain of data". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Reem Nasr (20 July 2015). "Musk: This Is What Caused the SpaceX Launch Failure". CNBC. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "SpaceX on Twitter: Update on this morning's anomaly". Twitter. 1 September 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Calandrelli E, Escher A (16 December 2016). "The top 15 events that happened in space in 2016". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Marco Santana (6 September 2016). "SpaceX customer vows to rebuild satellite in explosion aftermath". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Samantha Masunaga (9 September 2016). "Elon Musk: Launch pad explosion is 'most difficult and complex' failure in SpaceX's 14 years". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Loren Grush (5 November 2016). "Elon Musk says SpaceX finally knows what caused the latest rocket failure". The Verge. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Anomaly Updates". SpaceX. 1 September 2016. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Contact lost with three Starlink satellites, other 57 healthy". SpaceNews. 1 July 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "Starlink failures highlight space sustainability concerns". spacenews.com. 2 July 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Emily Shanklin (4 August 2008). "SpaceX receives US$20 million investment from Founder's Fund" (Press release). SpaceX. Archived from the original on 6 August 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Caleb Melby (12 March 2012). "How Elon Musk Became A Billionaire Twice Over". Forbes. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Elon Musk Anticipates Third IPO in Three Years With SpaceX". Bloomberg. 11 February 2012. Archived from the original on 21 July 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Jane Watts (27 April 2012). "Elon Musk on Why SpaceX Has the Right Stuff to Win the Space Race". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Privately-held SpaceX Worth Nearly $2.4 Billion or $20/Share, Double Its Pre-Mission Secondary Market Value Following Historic Success at the International Space Station". privco.com. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Ricardo Bilton (10 June 2012). "SpaceX's worth skyrockets to US$4.8 billion after successful mission". VentureBeat. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "SpaceX overview on secondmarket". SecondMarket. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012.

- "SpaceX raises $1 billion in funding from Google, Fidelity". NewsDaily. Reuters. 20 January 2015. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2017.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Brian Berger (20 January 2015). "SpaceX Confirms Google Investment". SpaceNews. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "SpaceX Is Now One of the World's Most Valuable Privately Held Companies". The New York Times. 27 July 2017. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.