Media ecology

Media ecology theory is the study of media, technology, and communication and how they affect human environments.[1] The theoretical concepts were proposed by Marshall McLuhan in 1964,[2] while the term media ecology was first formally introduced by Marshall McLuhan in 1962.[3]

Ecology in this context refers to the environment in which the medium is used – what they are and how they affect society.[4] Neil Postman states, "if in biology a 'medium' is something in which a bacterial culture grows (as in a Petri dish), in media ecology, the medium is 'a technology within which a [human] culture grows.'"[5] In other words, "Media ecology looks into the matter of how media of communication affect human perception, understanding, feeling, and value; and how our interaction with media facilitates or impedes our chances of survival. The word ecology implies the study of environments: their structure, content, and impact on people. An environment is, after all, a complex message system which imposes on human beings certain ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving."[6]

Media ecology argues that media act as extensions of the human senses in each era, and communication technology is the primary cause of social change.[7] McLuhan is famous for coining the phrase, "the medium is the message", which is an often-debated phrase believed to mean that the medium chosen to relay a message is just as important (if not more so) than the message itself.[2] McLuhan proposed that media influence the progression of society, and that significant periods of time and growth can be categorized by the rise of a specific technology during that period.

Additionally, scholars have compared media broadly to a system of infrastructure that connect the nature and culture of a society with media ecology being the study of "traffic" between the two.[8]

Background

Marshall McLuhan

In 1934, Marshall McLuhan enrolled as a student at Cambridge University, a school which pioneered modern literary criticism. During his studies at Cambridge, he became acquainted with one of his professors, I.A. Richards, a distinguished English professor, who would inspire McLuhan's later scholarly works. McLuhan admired Richards' approach to the critical view that English studies are themselves nothing but a study of the process of communication.[9] Richards believed that "words won't stay put and almost all verbal constructions are highly ambiguous".[9] This element of Richards' perspective on communication influenced the way in which McLuhan expressed many of his ideas using metaphors and phrases such as "The Global Village" and "The Medium Is the Message", two of his most well-known phrases that encapsulate the theory of media ecology.

McLuhan used the approaches of Richards, William Empson, and Harold Innis as an "entrée to the study of media".[9] However, it took many years of work before he was able to successfully fulfill their approaches. McLuhan determined that "if words were ambiguous and best studied not in terms of their 'content' but in terms of their effects in a given context and if the effects were often subliminal, the same might be true of other human artifacts, the wheel, the printing press, the telegraph and the TV".[9] This led to the emergence of his ideas on media ecology.

In addition to his scholarly work, McLuhan was also a well known media personality of his day.[10] He appeared on television shows, in magazine articles, and even had a small cameo in the movie Annie Hall.

Few theories receive the kind of household recognition that media ecology received, due directly to McLuhan's role as a pop culture icon.[11] He was an excellent debater and public speaker,[12] but his writing was not always what would normally pass in academia.

Neil Postman

Inspired by McLuhan, Neil Postman founded the Program in Media Ecology at New York University in 1971, as he further developed the theory McLuhan had established. According to Postman, media ecology emphasizes the environments in which communication and technologies operate and spread information and the effects these have on the receivers.[13] "Such information forms as the alphabet, the printed word, and television images are not mere instruments which make things easier for us. They are environments – like language itself, symbolic environments within which we discover, fashion, and express humanity in particular ways."[14]

Postman focused on media technology, process, and structure rather than content and considered making moral judgments the primary task of media ecology. "I don't see any point in studying media unless one does so within a moral or ethical context."[15] Postman's media ecology approach asks three questions: What are the moral implications of this bargain? Are the consequences more humanistic or antihumanistic? Do we, as a society, gain more than we lose, or do we lose more than we gain?[15]

Walter Ong

Walter J. Ong was a scholar with a master's degree in English who was once a student of McLuhan at the Saint Louis University.[16] The contributions of Ong standardized and gave credibility to the field of media ecology as worthy of academic scholarship.[16] Ong explored the changes in human thought and consciousness in the transition from a dominant oral culture to a literate one in his book Orality and Literacy.[17]

Ong's studies have greatly contributed to developing the concept of media ecology. Ong has written over 450 publications, many of which focused on the relation between conscious behavior and the evolution of the media, and he received the Media Ecology Association's Walter Benjamin Award for Outstanding Article for his paper, "Digitization Ancient and Modern: Beginnings of Writing and Today's Computers".[18]

North American, European and Eurasian versions

Media ecology is a contested term within media studies for it has different meanings in European and North American contexts. The North American definition refers to an interdisciplinary field of media theory and media design involving the study of media environments.[19] The European version of media ecology is a materialist investigation of media systems as complex dynamic systems.[20] In Russia, a similar theory was independently developed by Yuri Rozhdestvensky. In more than five monographs, Rozhdestvensky outlined the systematic changes which take place in society each time new communication media are introduced, and connected these changes to the challenges in politics, philosophy and education.[21] He is a founder of the vibrant school of ecology of culture.[22]

The European version of media ecology rejects the North American notion that ecology means environment. Ecology in this context is used "because it is one of the most expressive [terms] language currently has to indicate the massive and dynamic interrelation of processes and objects, beings and things, patterns and matter".[23] Following theorists such as Felix Guattari, Gregory Bateson, and Manuel De Landa, the European version of media ecology (as practiced by authors such as Matthew Fuller and Jussi Parikka) presents a post-structuralist political perspective on media as complex dynamical systems.

Other contributions

Along with McLuhan (McLuhan 1962), Postman (Postman 1985) and Harold Innis, media ecology draws from many authors, including the work of Walter Ong, Lewis Mumford, Jacques Ellul, Félix Guattari, Eric Havelock, Susanne Langer, Erving Goffman, Edward T. Hall, George Herbert Mead, Margaret Mead, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Benjamin Lee Whorf, and Gregory Bateson.

Core concepts

Assumptions of the theory

- Media are infused in every act and action in society.[24]

- Media fix our perceptions and organize our experiences.

- Media tie the world together.

These three assumptions can be understood as: media are everywhere all the time; media determine what we know and how we feel about what we know; and media connect us to others. Communication media have penetrated the lives of almost all people on the planet, arranging people into an interconnected human community.

McLuhan's media history

Marshall McLuhan defined media as anything requiring use of the human body. Under this definition, both computers and clothing can be identified as media. When a media is introduced it is adapted to human senses so that it becomes an extension of the individual, and its capabilities influence the whole of society, leading to change.[25] McLuhan states that there are three inventions that transformed the world: the phonetic alphabet, by virtue of its ability to make speech visible, which McLuhan argues gave rise to the discipline of rhetoric in ancient time and to the study of language and poetics, which was also known as grammar. The printing press in the nineteenth century and the telegraph led to both the modern newspaper and also to journalism as an academic pursuit.[26] The introduction of broadcasting in the form of radio, following on the heels of mass circulation newspapers, magazines, as well as the movies, resulted in the study of mass communication.[26] Due to these technologies, the world was taken from one era into the next. In order to understand the effects of symbolic environment, McLuhan splits history into four periods:[27] the Tribal Age, the Literacy Age, the Print Age, and the Electronic Age.

McLuhan states that, in order to study media effectively, one must study not only content but also the whole cultural environment in which media thrives.[28] He argues that using a detached view allows the individual to observe the phenomenon of the whole as it operates within the environment. The effects of media - speech, writing, printing, photograph, radio or television – should be studied within the social and cultural spheres impacted by this technology. McLuhan argues that all media, regardless of content, acts on the senses and reshapes sensory balance, further reshaping the society that created it. This differs from the viewpoints of scholars such as Neil Postman, who argue that society should take a moral view of new media whether good or bad.[29] McLuhan further notes that media introduced in the past brought gradual changes, which allowed people and society some time to adjust.

Tribal age

The first period in history that McLuhan describes is the Tribal Age. To McLuhan, this was a time of community, with the ear being the dominant sense organ. With everyone able to hear at the same time, listening to someone in a group a unifying act, deepening the feeling of community. In this set up, McLuhan argues, everything was more immediate, more present, and fostered more passion and spontaneity.

Literacy age

The second age McLuhan outlines is the Literacy Age, beginning with the invention of writing. To McLuhan, this was a time of private detachment, with the eye being the dominant sense organ. Turning sounds into visible objects radically altered the symbolic environment. Words were no longer alive and immediate, they were able to be read over and over again. Even though people would read the same words, the act of reading made communication an individual act, leading to more independent thought. Tribes didn't need to come together to get information anymore.

Print age

The third stage McLuhan describes is the Print Age, when individual media products were mass-produced due to the invention of the printing press. It gave the ability to reproduce the same text over and over again. With printing came a new visual stress: the portable book, which allowed people to carry media so they could read in privacy isolated from others. Libraries were created to hold these books and also gave freedom to be alienated from others and from their immediate surroundings.

Electronic age

Lastly, McLuhan describes the Electronic Age, otherwise included under the information age, as an era of instant communication and a return to an environment with simultaneous sounds and touch. It started with a device created by Samuel Morse's invention of the telegraph and led to the telephone, the cell phone, television, internet, DVD, video games, etc. This ability to communicate instantly returns people to the tradition of sound and touch rather than sight. McLuhan argues that being able to be in constant contact with the world becomes a nosy generation where everyone knows everyone's business and everyone's business is everyone else's. This phenomenon is called the global village.[2]

Later scholars have described the growth of open access and open science, with their potential for highly distributed and low cost publishing reaching much larger audiences, as a potential "de-professionalizing force".[30]

Updating the ages

Robert K. Logan is professor emeritus of physics at the University of Toronto and Chief Scientist of the Strategic Innovation Lab at the Ontario College of Art and Design. He worked collaboratively with Marshall McLuhan at the University of Toronto, co-publishing various works and producing his own works, heavily inspired by McLuhan. Logan updates the era of communications, adding two new eras:

- Age of nonverbal mimetic communication (characteristic of archaic Homo sapiens)

- Age of orality

- Age of literacy

- Age of electric mass media

- Age of digital interactive media, or 'new media'[31]

In addition, through the study of media ecology, it is argued that through technological advancements in media, many societies have become a "participatory culture". Tom Valcanis argues that this very easily witnessed by looking at the rise of Apple's iPhone. "If the technology is the medium in which a culture grows, the interactive and user oriented nature of these technologies have given rise to a participatory and 'mash-up' culture in which the ways of producing and accessing content are deconstructed, uploaded, mixed, converged, and reconstructed through computers and smartphones mediated by online platforms; it becomes a 'participatory culture'..."[32]

'The medium is the message'

"The medium is the message"[2] is the most famous insight from McLuhan, and is one of the concepts that separates the North American theory from the European theory. Instead of emphasizing the information content, McLuhan highlighted the importance of medium characteristics which can influence and even decide the content. He proposed that it is the media format that affects and changes on people and society.[33]

For example, traditional media is an extension of the human body, while the new media is the extension of the human nervous system. The emergence of new media will change the equilibrium between human sensual organs and affect human psychology and society. The extension of human senses will change our thoughts and behaviors and the ways we perceive the world. That's why McLuhan believed when a new medium appears, no matter what the concrete content it transmits, the new form of communication brings in itself a force that causes social transformation.[34]

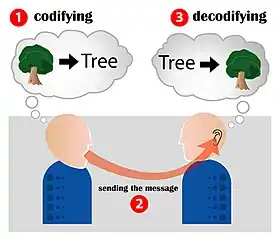

We are accustomed to thinking the message is separate from a medium. McLuhan saw the message and the medium to mean the same thing. The audience is normally focused on the content and overlooks the medium. What we forget is that the content cannot exist outside of the way that it is mediated. McLuhan recognized that the way media work as environments is because we are so immersed in them. "It is the medium that has the greatest impact in human affairs, not specific messages we send or receive."[35] The media shape us because we partake in them over and over until they become a part of us.

Different mediums emphasize different senses and encourage different habits, so engaging in this medium day after day conditions our senses.[15] Different forms of media also affect what their meaning and impact will be. The form of medium and mode of information determines who will have access, how much information will be distributed, how fast it will be transmitted, how far it will go, and, most importantly, what form it will be displayed.[35] With society being formed around the dominant medium of the day, the specific medium of communication makes a remarkable difference.

The metaphor

The key elements to media ecology have been largely attributed to Marshall McLuhan, who coined the statement "the medium is the message". Levinson furthers McLuhan's statement by stating that "the way we communicate, often taken for granted, often determines what we communicate, and therein just about everything else in life and society".[36] McLuhan gave a center of gravity, a moral compass to media ecology which was later adapted and formally introduced by Neil Postman[36]

The very foundation for this theory is based on a metaphor that provides a model for understanding the new territory, offers a vocabulary, and indicates in which directions to continue exploring.[37] As Carlos Scolari states, "the configuration of media ecology in the 1960s and 1970s was part of a broader process of the general application of the ecological metaphor to the social sciences and humanities in the postwar period.[37] There is still a scholarly debate over who coined the phrase "the medium is the message". Author Niall Stephens argues that while most attribute the metaphor to Marshall McLuhan, it is better directed to Neil Postman, who helped popularize McLuhan under the banner of "media ecology".[38]

Scholar Janet Sternberg has a different take on the metaphor- using her own metaphor to make sense of it all. Sternberg applies the Chinese "yin/ yang" metaphor to media ecology as a means of better understanding the divergence among scholars. She states that there are two basic intellectual traditions that can be distinguished in the field: the "yang" tradition of studying media as environments, focusing on mass communication and on intrapersonal communication and the "yin" tradition is studying environments as media, emphasizing interpersonal communication.[39]

Connection to general systems theory

While general systems theory originated in 1928 in the Ph.D. thesis of Ludwig von Bertalanffy. Robert Logan summarizes a general system as "one that is composed of interacting and interrelated components such as an understanding of it must entail considering the general system as a whole and not as a collection of individual components".[40]

Logan argues that general systems theory, as well as cybernetics, complexity theory, and emergent dynamics, and media ecology "cross pollinate each other" in that, "a general system is a medium" due to the non-linear aspects of messages and that general systems are "quasi-deterministic".[40]

This thinking is in line with McLuhan who once wrote, "A new medium is never an addition to an old one, nor does it leave the old one in peace. It never ceases to oppress the older media until it finds new shapes and positions for them."[40]

Global village

Marshall McLuhan used the phrase global village to characterize an end to isolation: "humans can no longer live in isolation, but rather will always be connected by continuous and instantaneous electronic media".[41] McLuhan addresses the idea of a global village in his book The Gutenberg Galaxy saying, "Such is the character of a village or, since electric media, such is also the character of global village. And it is the advertising and PR community that is most aware of this basic new dimension of global interdependence".[42]

Technology, especially electronic media in today's age, makes the world increasingly interconnected. Socially, economically, politically, culturally, what happens in one part of the world has a ripple effect into other countries.

This seems like a common sense idea today, where the internet makes it possible to check news stories around the globe, and social media connects individuals regardless of location. However, in McLuhan's day, the global village was just becoming possible due to technology like television and long distance phone calls. This concept has become one of the most prolific and understandable ideas to come out of media ecology, and has spurred significant research in many areas. It is especially relevant in today's society, where the internet, social media, and other new media have made the world a smaller place, and today many researchers give McLuhan credit for his foresight.[31][43]

Of note is McLuhan's insistence that the world becoming a global village should lead to more global responsibility. Technology has created an interconnected world, and with that should come concern for global events and occurrences outside one's own community.[1] Postman builds on this concept with the idea of teaching the narrative of 'Spaceship Earth' where students are taught the importance of everyone taking care of planet earth as a fragile system of diversity both biological and cultural;[44] however, the original person to coin the term 'Spaceship Earth' was futurists Buckminster Fuller, who once said, "I've often heard people say: 'I wonder what it would feel like to board a spaceship,' and the answer is very simple. What does it feel like? That's all we have experienced. We're all astronauts on a little spaceship called earth."[45]

Critics do worry though, that in creating a truly global village, some cultures will become extinct due to larger or more dominant cultures imposing their beliefs and practices.[46]

The idea of the global village helps to conceptualize globalization within society. Michael Plugh writes, "[The] village is an environment produced both by technological change and human imagination of this globalized environment."[47]

Additionally, the rise in media communication technology has uniformed the way individuals across the globe process information. Plugh says, "Where literate societies exchange an 'eye for an ear,' according to McLuhan, emphasizing the linear and sequential order of the world, electronic technology retrievers the total awareness of environment, characteristic of oral cultures, yet to an extended or 'global' level."[47]

Hot vs. cool media

McLuhan developed an idea called hot and cold media.[48] Hot media is high-definition communication that demands little involvement from the audience and concentrates on one sensory organ at a time. This type of media requires no interpretation because it give all the information necessary to comprehend. Some examples of hot media include radio, books, and lectures. Cool media is media that demands active involvement from the audience, requiring the audience to be active and provide information by mentally participating. This is multi-sensory participation. Some examples of cool media are TV, seminars, and cartoons.[49]

"McLuhan frequently referred to a chart that hung in his seminar room at the University of Toronto. This was a type of shorthand for understanding the differences between hot and cool media, characterized by their emphasis on the eye or the ear."[50]

- Eye: left hemisphere (hot) controls right side of the body; visual; speech; verbal; analytical; mathematical; linear; detailed; sequential; controlled; intellectual; dominant worldly;quantitative; active; sequential ordering

- Ear: right hemisphere (cool) controls the left side of the body; spatial; musical; acoustic; holistic; artistic; symbolic; simultaneous; emotional; creative; minor; spiritual; qualitative; receptive; synthetic; gestalt; facial recognition; simultaneous comprehension; perception of abstract patterns

Laws of media

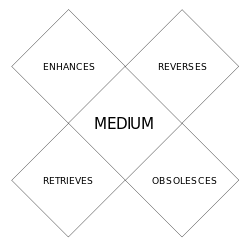

Another aspect of media ecology is the laws of media, which McLuhan outlined with his son Eric McLuhan to further explain the influence of technology on society.[51] The laws of media theory are depicted by a tetrad, which poses questions about various media, with the goal of developing peoples' critical thinking skills and to prepare people for "the social and physical chaos" that accompany every technological advancement or development. There is no specific order to the laws of media, as the effects occur simultaneously and form a feedback loop: technology impacts society, which then impacts the development of technology.

The four effects, as depicted in the tetrad of media effects are:[51]

- Enhancement: What does the medium enhance? Media can enhance various social interactions, such as the telephone, which reduced the need for face-to-face interactions.

- Obsolescence: What does the medium obsolesce? Technological advancements can render older media obsolete, as television did for the radio. This does not necessarily mean that the older medium is completely eradicated however, as radio, for example, is still in use today.

- Retrieval: What does the medium retrieve? New media can also spur a restoration of older forms of media, which the new forms may not be able to incorporate into their new technologies. For example, the Internet has promoted new forms of social conversations, which may have been lost through television.

- Reversal: What will the medium reverse? When a medium is overwhelmed due to its own nature, "pushed to the limit of its potential,"[51] it ceases to have functional utility and can cause a reversion to older media.

Criticism

Technological determinism

A significant criticism of this theory is a result of its deterministic approach. Determinism insists that all of society is a result of or effected by one central condition. In some cases the condition can be language (linguistic determinism), religion (theological determinism), financial (economic determinism). In the case of McLuhan, Postman and Media Ecology, technology is the sole determinant for society and by breaking up time in measures of man's technological achievements they can be classified as technological determinism. According to Postman, "The printing press, the computer, and television are not therefore simply machines which convey information. They are metaphors through which we conceptualize reality in one way or another. They will classify the world for us, sequence it, frame it, enlarge it, reduce it, argue a case for what it is like. Through these media metaphors, we do not see the world as it is. We see it as our coding systems are. Such is the power of the form of information."[52] Postman has also stated that "a medium is a technology within which a culture grows; that is to say, it gives form to a culture's politics, social organization, and habitual ways of thinking".[53]

Scholars such as Michael Zimmer view McLuhan and his "Medium is the Message" theory as a prime example of technological determinism:

...an overarching thread in media ecological scholarship, exemplified by McLuhan's (1964/1994) assertion that "the medium is the message", the technological bias of a medium carries greater importance than the particular message it is delivering. McLuhan saw changes in the dominant medium of communication as the main determinant of major changes in society, culture, and the individual. This McLuhanesque logic, which rests at the center of the media ecology tradition, is often criticized for its media determinism. Seeing the biases of media technologies as the primary force for social and cultural change resembles the hard technological determinism of the embodied theory of technological bias.[54]

The critics of such a deterministic approach could be theorists who practice other forms of determinism, such as economic determinism. Theorists such as John Fekete believes that McLuhan is oversimplifying the world "by denying that human action is itself responsible for the changes that our socio-cultural world is undergoing and will undergo, McLuhan necessarily denies that a critical attitude is morally significant or practically important."[55]

Lance Strate, on the other hand, argues that McLuhan's theories are in no way deterministic. "McLuhan never actually used the term, "determinism," nor did he argue against human agency. In his bestselling book, The Medium is the Message, he wrote, "there is absolutely no inevitability as long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening" (McLuhan & Fiore, 1967, p. 25). John Culkin (1967) summed up McLuhan's position with the quote, "we shape our tools and thereafter they shape us",[56] suggesting a transactional approach to media."[57] This statement from Strate would define McLuhan and Media Ecology as "soft determinism" opposed to "hard determinism" with the difference being that "hard determinism" indicates that changes to society happen with no input or control from the members of that society, whereas "soft determinism" would argue that the changes are pushed by technology but free will and agency of the members of society ultimately have a chance to influence the outcome.

While ideas of technological determinism generally have negative connotations, technology philosopher Peter-Paul Verbeek argued that technologies are "inherently moral agents" and their development is a "moral enterprise".[58][59][60]

Disruptions to existing systems

While advancing technologies allow for the study of media ecology, they also frequently disrupt the existing system of communication as they emerge. In general, four types of disruption can occur within the study of media ecology.[61]

- New Technologies

- New Audiences

- New Authority

- New Rhetoric

One example where this can be seen is in do-it-yourself education. Advancing technologies have also expanded access to do-it-yourself (DIY) education. DIY education can be defined to include "any attempt to decentralize or disrupt traditional place-based educational models through the sometimes collective, other times individual use of digital media".[62] Through an analysis of media ecology the impact of these new technologies on society can better be understood.

Mobility and modality

Various scholars have looked to media ecology theory through different lenses to better understand this theory in the 21st century. While Sternberg applied the yin/yang metaphor to make sense of the theory, Julia Hildebrand and John Dimmick et al. create a new languages of modality. As such, contributing to a new rhetoric to contextualize media ecology in the age of the internet, social media, and advances in technologies. Hildebrand uses the conceptualization of 'mediated mobilities' to illustrate a connection between media ecology and mobilities research, ultimately making a case for a modal medium theory. She looks into the articles of Emily Keightley and Anna Reading, and Lance Strate as a basis for her case. In 1999, Lance Strate states media ecology theory is "grammar and rhetoric, semiotics and systems theory, the history and the philosophy of technology".[63] Hildebrand explains that Strate's concept of media ecology is not limited to the study of information and communication technology but technology, in general. Technology is therefore implying materialities and mobilities that is put into relation with media ecology. As Hildebrand states, "[e]nvironments are created and shaped by different media and modes and the physical, virtual, and mental processes and travels they generate".[63] Much like media ecology, mobilities research talk about a "flow" that shapes the environment, creating a contact zones. Dimmick furthers this explanation with the concept of interstices as the intersection of communication environments and issues of mobility.[64] He quotes two scholars, Hemment and Caronia, to contextualize his new word. Hemment argues that mobile technologies create a place out of space and time, a kind of "nonspace" or "nonplace" considering they are independent from the variables of space and time. Caronia notes that such technologies extend media to creating empty space and places.[64]

The medium is not the message

McLuhan's critics state the medium is not the message. They believe that we are dealing with a mathematical equation where medium equals x and message equals y. Accordingly, x = y, but really "the medium is the message" is a metaphor not an equation. His critics also believe McLuhan is denying the content altogether, when really McLuhan was just trying to show the content in its secondary role in relation to the medium. McLuhan says technology is an "extension of man" and when the way we physically sense the world changes, how we perceive it will also collectively change, but the content may or may not affect this change in perception. McLuhan said that the user is the content, and this means that the user must interpret and process what they receive, finding sense in their own environments.[65]

One of McLuhan's high-profile critics was Umberto Eco. Eco comes from background in semiotics, which goes beyond linguistics in that it studies all forms of communication. He reflected that a cartoon of a cannibal wearing an alarm clock as a necklace was counter to McLuhan's assertion that the invention of clocks created a concept of time as consistently separated space. While it could mean this it could also take on different meanings as in the depiction of the cannibal. The medium is not the message. An individual's interpretation can vary. Believing this to be true Eco says, "It is equally untrue that acting on the form and content of the message can convert the person receiving it." In doing this Eco merges form and content, the separation of which is the basis of McLuhan's assertion. McLuhan does not offer a theory of communication. He instead investigates the effects of all media mediums between the human body and its physical environment, including language.[66]

Others

The North American variant of media ecology is viewed by numerous theorists such as John Fekete[55] and Neil Compton as meaningless or "McLuhanacy". According to Compton, it had been next to impossible to escape knowing about McLuhan and his theory as the media embraced them. Compton wrote, "it would be better for McLuhan if his oversimplifications did not happen to coincide with the pretensions of young status-hungry advertising executives and producers, who eagerly provide him with a ready-made claque, exposure on the media, and a substantial income from addresses and conventions."[67] Theorists such as Jonathan Miller claim that McLuhan used a subjective approach to make objective claims, comparing McLuhan's willingness to back away from a "probe" if he did not find the desired results to that of an objective scientist who would not abandon it so easily.[68] These theorists against McLuhan's idea, such as Raymond Rosenthal, also believe that he lacked the scientific evidence to support his claims:[35] "McLuhan's books are not scientific in any respect; they are wrapped however in the dark, mysterious folds of the scientific ideology."[67] Additionally, As Lance Strate said: "Other critics complain that media ecology scholars like McLuhan, Havelock, and Ong put forth a "Great Divide" theory, exaggerating, for example, the difference between orality and literacy, or the alphabet and hieroglyphics.

Research

New media

Many ecologists are using media ecology as an analytical framework, to explore whether the current new media has a "new" stranglehold on culture or are they simply extensions of what we have already experienced. The new media is characterised by the idea of web 2.0. It was coined in 2003 and popularized by a media consultant, Tim O'Reilly. He argues that a particular assemblage of software, hardware and sociality have brought about 'the widespread sense that there's something qualitatively different about today's Web. This shift is characterised by co-creativity, participation and openness, represented by software that support for example, wiki-based ways of creating and accessing knowledge, social networking sites, blogging, tagging and 'mash ups'.[69] The interactive and user-oriented nature of these technologies have transformed the global culture into a participatory culture which proves Neil Postman's saying "technological change is not additive; it is ecological".

As new media power takes on new dimension in the digital realm, some scholars begin to focus on defending the democratic potentialities of the Internet on the perspective of corporate impermeability. Today, corporate encroachment in cyberspace is changing the balance of power in the new media ecology, which "portends a new set of social relationships based on commercial exploitation".[70] Many social network websites inject customized advertisements into the steady stream of personal communication. It is called commercial incursion which converts user-generated content into fodder for marketers and advertisers.[70] So the control rests with the owners rather than the participants. It is necessary for online participants to be prepared to act consciously to resist the enclosure of digital commons.

There is some recent research that puts the emphasis on the youth, the future of the society who is at the forefront of new media environment. Each generation, with its respective worldview, is equipped with certain media grammar and media literacy in its youth.[71] As each generation inherits an idiosyncratic media structure, those born into the age of radio perceive the world differently from those born into the age of television.[71] The nature of new generation is also influenced by the nature of the new media.

According to the media ecology theory, analyzing today's generational identity through the lens of media technologies themselves can be more productive than focusing on media content. Media ecologists employ a media ecology interpretative framework to deconstruct how today's new media environment increasingly mirrors the values and character attributed to young people. Here are some typical characteristics of the new generation: first, it is "the world's first generation to grow up thinking of itself as global. The internet and satellite television networks are just two of the myriad technologies that have made this possible."[72] Second, "there may actually be no unified ethos".[73] With "hundreds of cable channels and thousands of computer conferences, young generation might be able to isolate themselves within their own extremely opinionated forces".[74]

Education

In 2009 a study was published by Cleora D'Arcy, Darin Eastburn and Bertram Bruce entitled "How Media Ecologies Can Address Diverse Student Needs".[75] The purpose of this study was to use Media Ecology in order to determine which media is perceived as the most useful as an instructional tool in post-secondary education. This study specifically analyzed and tested "new media" such as podcasts, blogs, websites, and discussion forums with other media, such as traditional text books, lectures, and handouts. Ultimately comparing "hot" and "cold" media at today's standard of the terms. The result of the study, which included student surveys, indicated that a mixture of media was the most "valued" method of instruction, however more interactive media enhanced student learning.

Application and case studies

There is significant research being done on the rise of social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and their influence on communication in society. Some of that research is being done through a media ecology perspective. Below are some examples:

Social media activism

While many people utilize social media platforms to stay in contact with friends and family, socialize, or even shop,[76] these platforms have also been pivotal for social activism. Social media activism and hashtag activism have become popular ways to gain mainstream media and public attention for causes, and to facilitate protests.

Thomas Poell researched the influence of social media on the 2010 protests of the Toronto G20 summit.[77] In the article, he focused on identifying how each social media site was used independently, and then how they were integrated together. The sites analyzed were Twitter, YouTube, Flickr, Facebook, and an open publishing website. What he found is that each site is used differently for social media activism. While this kind of activism was originally looked at as a way to promote causes and encourage long term focus on the issues, Poell found that sites like Twitter and Facebook tend to do the opposite. Posts center around photographs and videos of action during protests and rallies, not on the issues that are being protested. This would be an example of hot media, because the user can scroll through photos or watch videos without being otherwise engaged, instead of cool media where the user has to be more involved. Additionally, because activists are using sites they do not own, the social media platform actually has more control over the information being posted. For example, Twitter no longer allows unrestricted access to all posts made with a certain hashtag after a period of time. This seems to mean that the issue being highlighted fades over time.

Additionally, Heather Crandall and Carolyn M. Cunningham focus on hashtag activism, where activists use metadata tags to focus on specific issues (ex: #activism).[78] They did not look at one specific protest like the G20 summit, but rather at the benefits and criticisms of hashtag activism as a whole. They discuss that social media is a new media ecology, one where users can connect and share ideas without boundaries. This falls under McLuhan's idea of the world as a global village. By using hashtags, activists are able to bring awareness to social issues. Crandall and Cunningham point out that this is both beautiful and interesting, because it encourages learning, conversations, and community for social justice, and that it is also dark and confusing, because the open environment of the internet also allows hashtags to be used for hate speech and threats of violence. Also, they posit that hashtag activism is pointed and stacked, in that hashtags are often short lived, and the user has to be able to navigate the platform and understand hashtags in order to gain knowledge of the issue. When viewed through media ecology, hashtag activism is changing the way people encounter and engage in social justice.

Arab Spring: Egypt and Iran

Mark Allen Peterson of in the Department of Anthropology at Miami University published an article in the Summer of 2011 comparing the media ecology of 1970s Iran to that in Egypt in 2011. The article, title "Egypt's Media Ecology in a Time of Revolution"[79] looks at the difference that social media made in the Egyptian uprising and makes two observations: social media extends the "grapevine" network and that social media, despite the result of the uprising, completely changes the "mediascape" of Egypt. One dramatic difference between the two uprising noticed by Peterson is the ultimate position of the media of choice during each in the end. On the one hand, Iran's news media, the primary source of information at that time, reverted to its original role, while the Egyptian use of social media changed the media of choice for Egypt.

Peterson's study compared his observations to that of William Beeman, who in 1984 published an essay, "The cultural role of the media in Iran: The revolution of 1978–1979 and after"[80] on the media ecology of Iran. Beeman's ultimate conclusion of his review of the Iranian Revolution followed that of what you would expect to find from most media ecologists: "At times newly introduced mass media have produced revolutionary effects in the societal management of time and energy as they forged new spaces for themselves. Thus media are cultural forces as well as cultural objects. In operation, they produce specific cultural effects that cannot be easily predicted."[80]:147

Although there were many similarities between the Iranian Revolution and Egyptian revolutions, such as censorship in media, including newspaper and television, the one major difference was the availability of the internet and social media as a tool to spread messages and increase awareness in Egypt. Social media in 2011's uprising was equivalent to the use of cassette tapes in Iran in the 1970s. The tapes provided a way to spread information that could not be as easily censored and was repeatable through the country.[79]:5 The rise of social media helped free Egyptians from censorship of other media. In this case, the medium was the message, a message of freedom and by the Egyptian government's attempt to also censor this medium, they only managed to spread the message further and faster:

Although we may never know the true impact, in fact it likely sped up the regime's fall. In the absence of new technologies, people were forced to rely on traditional means of communication, including knocking on doors, going to the mosque, assembling in the street, or other central gathering places. Thomas Schelling won a Nobel prize in part for discovering that in the absence of information, people will coordinate by selecting a focal point that seems natural, special or relevant to them. Given the protests, Tahrir Square was the obvious focal point. By blocking the Internet, the government inadvertently fueled dissent and galvanized international support for the people of Egypt. (Bowman 2011)[81]

Since 2011, leaders of the protest continue to utilize social media as a method to push democratic reform.[79]:4 According to Peterson the role of social media in Egypt is also evolving the political culture as even state figures are beginning to make announcements using social media rather than more traditional forms of media.[79]:5

Gezi protests: Turkey

Much like the Arab Spring, the Gezi protests were an environmental sit-in that ultimately turned into a social movement based on the influence of various forms of social media. Rolien Hoyng and Murat Es coin the term "Turkish media ecology" to evoke a sense of particularly on the part of Turkey's relationship with media outlets and platforms.[82] In Turkey, media censorship and control by state institutions most directly impact broadcast media. Both authors emphasize how "…media-ecological affordances are conditioned and modulated by legal frameworks and institutional-political rationalities".[82] They also note that such censored media ecology forms a 'fertile milieu' for the proliferation of conspiracy theories which both feed on one another.[82] Scholar Gulizar Haciyakupoglu examines how social media influenced the protests, specifically looking at how trust was built and maintained among protestors across multiple platforms.[83] From his interviews, the scholar extrapolates that "closed groups" like Whatsapp and Facebook "...allowed the circulation of confidential and trustworthy information among first- and second-degree friends" whereas Twitter was used for "rapid acquisition of logistic information" that became important during the protest.[83]

15M movement: Spain

Emiliano Treré looks to the media ecology metaphor as a way to investigate the relationship between social movements, media ecologies and communication technologies through the lens of Spain's anti-austerity movement, also called the "15M movement". Treré states how most scholars believe the media ecological framework is particularly suited for the study of the social movements/media nexus "...because of its ability to provide fine-tuned explorations of the multiplicity, the interconnections, the dynamic evolution of old and new media forms for social change".[84] The author also agrees with Scolari (mentioned above) that the key reflections from the theory is especially beneficial for modern analysis on media and social events.[84] One such application is seen with the analysis of Spain's 15M movement. Facing different degrees of mainstream media manipulation and bias "various media activists turned to Web TV services, radical online tools, Twitter and Facebook among others to organize, and contrast the official narratives of the protest."[84] Scholar John Postill argues that Twitter, among all the types of technologies used, produced a greater effect for setting and tone and agenda of the movement.[85] Such appropriation of technologies demonstrates the dichotomies between old and new technologies that in term created a kind of "technological sovereignty" among activists.[84] Media ecology has the innate ability to aggregate different analytical approaches to better understand the technology that is at place during such a protest. Postill and other scholars ultimately look to a new age in social activism, where "viral" posts shared by media professionals and amateurs empower people and become the rising voice for the future of democracy in Spain.[85]

See also

Notes

- West, Richard; Turner, Lynn H. (2014). Introducing Communication Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 454–472. ISBN 978-0-07-353428-2.

- McLuhan, Marshall (1964). Understanding media. New York: Mentor. ISBN 978-0262631594.

- Gencarelli, T. F. (2006). Perspectives on culture, technology, and communication: The media ecology tradition. Gencarelli: NJ: Hampton. pp. 201–225.

- Understanding Me: Lectures and Interviews, by Marshall McLuhan, edited by Stephanie McLuhan and David Staines, Foreword by Tom Wolfe. MIT Press, 2004, p. 271

- Postman, N. (2006). Media Ecology Education. Explorations in Media Ecology, 5(1), 5–14. doi:10.1386/eme.5.1.5_1

- Postman, Neil. "What is Media Ecology?". Media Ecology Association. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 2 Oct 2016.

- Hakanen, Ernest A. (2007). Branding the teleself: Media effects discourse and the changing self. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-1734-7.

- "Infrastructuralism: Media as Traffic between Nature and Culture.: EBSCOhost". web.b.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- Marchand, Philip (1998). Marshall McLuhan: The Medium and The Messenger : A Biography (Rev Sub ed.). Massachusetts: The MIT Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-262-63186-0.

- "Who was Marshall McLuhan? – The Estate of Marshall McLuhan". marshallmcluhan.com. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- Mullen, Megan (2006). "Coming to Terms with the Future He Foresaw : Marshall McLuhan's 'Understanding Media'". Technology and Culture. 47 (2): 373–380. doi:10.1353/tech.2006.0143. JSTOR 40061070. S2CID 110819701.

- Marchand, Phillip (1989). Marshall McLuhan: The medium and the messenger. New York: Ticknor & Fields. pp. 153. ISBN 978-0899194851.

- Postman, Neil. "What is Media Ecology." Media Ecology Association. 2009. Web. 29 Sept 2014.

- Postman, Neil. "Teaching as a conserving activity." Instructor 89.4 (1979).

- Griffin, Em. A First Look at Communication Theory. 7th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill , 2009. Print

- Lance, Strate (2006). Echoes and reflections : on media ecology as a field of study. Cresskill, N.J.: Hampton Press. ISBN 9781572737259. OCLC 631683671.

- Ong, Walter J. (2002). Orality and literacy : the technologizing of the word. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415281829. OCLC 49874897.

- "About Walter J. Ong, S.J." www.slu.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- Nystrom, Christine. "What is Media Ecology?". Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Strate, Lance (2004). "A Media Ecology Review" (PDF). Communication Research Trends. 23: 28–31. ISSN 0144-4646. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Polski, M.; Gorman, L. (2012). "Yuri Rozhdestvensky vs. MArshall McLuhan: A triumph vs. a Vortex". Explorations in Media Ecology. 10 (3–4): 263–278. doi:10.1386/eme.10.3-4.263_1. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2014-01-31.

- Polski, M. (2013). Media Ecology Pedagogy—Art or Techne?. MEA conference. Grand Rapids, MI.

- Fuller, Matthew (2005). Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture. Leonardo Series. MIT Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780262062473.

- West, Richard; Lynn H. Turner (2010). "25". Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application (4 ed.). New York: Mc Graw Hill. pp. 428–430. ISBN 978-0-07-338507-5.

- Rogaway, P. (1994). Marshall McLuhan interview from Playboy, 1969. ECS 188: Ethics in the Age of Technology, University of California, Davis

- Strate, L. (2008). Media ecology scholars also use broad categories like oral, scribal, print, and electronic cultures. Studying media as media: McLuhan and the media ecology approach.

- McLuhan, M.; Fiore Q.; Agel J. (1967). The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. San Francisco: HardWired. ISBN 978-1-888869-02-6.

- Delicata, N. (2008). Marshall McLuhan: Media Ecologist and Educator. Ultimate Reality and Meaning, 31(4), 314-341.

- Postman, N. (2000, June). The humanism of media ecology. In Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association (Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 10-16)

- Dickel, Sascha (2016-09-21). "Trust in technologies? Science after de-professionalization". Journal of Science Communication. 15 (5): C03. doi:10.22323/2.15050303. ISSN 1824-2049.

- Logan, Robert K. (2010). Understanding New Media: Extending Marshall McLuhan. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. pp. 28–31. ISBN 9781433111266.

- "AN IPHONE IN EVERY HAND: MEDIA ECOLOGY, COMMUNICATION STRUCTURES, AND THE G...: EBSCOhost". web.a.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- McLuhan, Marshall, 1911–1980 (2001). The medium is the massage : an inventory of effects. Fiore, Quentin. Berkeley, CA. ISBN 9781584230700. OCLC 47679653.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chen, Xianhong; Guilan Ding (November 2009). "SPECIAL COMMENTARY New media as relations". Chinese Journal of Communication. 2 (3): 367–369. doi:10.1080/17544750903209242. S2CID 58502045.

- Strate, Lance. "Studying Media as Media: McLuhan and the Media Ecology Approach." MediaTropes eJournal. 1. (2008): 1–16. Web. 28 Nov. 2011.

- Levinson, Paul (2000). "McLuhan and Media Ecology" (PDF). Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association. 1: 17–22.

- Scolari, Carlos A. (2012-04-09). "Media Ecology: Exploring the Metaphor to Expand the Theory" (PDF). Communication Theory. 22 (2): 204–225. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01404.x. hdl:10230/25652. ISSN 1050-3293.

- Stephens, Niall (2014). "Toward a More Substantive Media Ecology: Postman's Metaphor Versus Posthuman Futures". International Journal of Communication. 8: 2027–2045.

- Sternberg, Janet (2002). "The Yin and Yang of Media Ecology" (PDF). MEA Convention Proceedings. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-13.

- Robert Logan (June 2015). "General Systems Theory and Media Ecology: Parallel Disciplines that Inform Each Other" (PDF). Explorations in Media Ecology. 14: 39–51. doi:10.1386/eme.14.1-2.39_1.

- West, Richard (2009-02-17). Introducing communication theory: analysis and application. McGraw-Hill. p. 432. ISBN 9780073385075.

- Tremblay, Gaetan (2012). "From Marshall McLuhan to Harold Innis, or From the Global Village to the World Empire". Canadian Journal of Communication. 37 (4): 572. doi:10.22230/cjc.2012v37n4a2662.

- Walkosz, Barbara J.; Tessa Jolls; Mary Ann Sund (2008). Global/Local: Media Literacy for the Global Village (PDF). Proc. of International Media Literacy Research Forum, London. Medialit.org. OfCom.

- "The Harvard Educational Review – HEPG". hepg.org. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- "Spaceship Earth | The Buckminster Fuller Institute". www.bfi.org. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- K, Dixon, Violet (2009-01-01). "Understanding the Implications of a Global Village". Inquiries Journal. 1 (11).

- Plugh, Michael (2014). "Global village: Globalization through a media ecology lens". Explorations in Media Ecology. 13 (3–4): 219–235. doi:10.1386/eme.13.3-4.219_1.

- McLuhan, Marshall, and Quentin Fiore. "The medium is the message." New York 123 (1967): 126–128.

- McLuhan, Marshall; Lewis H. Lapham (1994). Understanding media: The Extension of Man. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-63159-4.

- Harold Innis: The Philosophical Historian. An Exchange of Ideas Between Prof. Marshall McLuhan and Prof. Eric A. Havelock," recorded at Innis College, Toronto, October 14, 1978.

- McLuhan, Marshall; Eric McLuhan (1988). Laws of media: The new science. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-8020-7715-8.

- Postman, Teaching as a Conserving Activity (1979), p. 39

- Postman, Neil. "The Humanism of Media Ecology". Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- Zimmer, Michael (2005). Media Ecology and Value Sensitive Design: A Combined Approach to Understanding the Biases of Media Technology. Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association. 6.

- Fekete, John (1973). "McLuhanacy: Counterrevolution in cultural theory". Telos. 1973 (15): 75–123. doi:10.3817/0373015075. S2CID 147429966.

- Culkin, J. (1967). "Each culture develops its own sense ratio to meet the demands of its environment". In G. Stearn (ed.). McLuhan: Hot and cool. New York: New American Library. pp. 49–57.

- Strate, Lance (2008). "Studying media as media: McLuhan and the media ecology approach". MediaTropes. 1 (1): 133.

- Grosswiler, Paul (2016). "Cussing the buzz-saw, or, the medium is the morality of Peter-Paul Verbeek". Explorations in Media Ecology. 15 (2): 129–139. doi:10.1386/eme.15.2.129_1.

- Peterson, M.; Spahn, A. (2011). "Can Technological Artefacts Be Moral Agents?". Science and Engineering Ethics. 17 (3): 411–424. doi:10.1007/s11948-010-9241-3. PMC 3183318. PMID 20927601.

- Peter-Paul Verbeek (1 March 2008). "Obstetric Ultrasound and the Technological Mediation of Morality: A Postphenomenological Analysis". Human Studies. 31 (1): 11–26. doi:10.1007/s10746-007-9079-0. S2CID 145663406.

- Soukup, Paul A. (2017). "A shifting media ecology: What the age of Luther can teach us". Media Development. 64 (2): 5–10.

- John Dowd (June 2014). "A media ecological analysis of do-it-yourself education: Exploring relationships between the symbolic and the material realms of human action". Explorations in Media Ecology. 13 (2): 155–175. doi:10.1386/eme.13.2.155_1.

- Hildebrand, Julia M (2017-05-11). "Modal media: connecting media ecology and mobilities research". Media, Culture & Society. 40 (3): 348–364. doi:10.1177/0163443717707343. ISSN 0163-4437. S2CID 149286101.

- Dimmick, John; Feaster, John Christian; Hoplamazian, Gregory J. (2010-05-18). "News in the interstices: The niches of mobile media in space and time". New Media & Society. 13 (1): 23–39. doi:10.1177/1461444810363452. ISSN 1461-4448. S2CID 41645995.

- Grosswiler, Paul (2010). Transforming McLuhan: Cultural, Critical, and Postmodern Perspectives. p.52: Peter Lang. p. 238. ISBN 9781433110672.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Gordon, W. Terrance (2010). McLuhan: A Guide for the Perplexed. London, GBR: Continuum International Publishing. p. 214. ISBN 9781441143808.

- Rosenthal, Raymond (1968). McLuhan: Pro and Con. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 308.

- Miller, Jonathan (1971). Marshall McLuhan. New York: Viking Press. pp. 133. ISBN 978-0670019120.

- O'Reilly, Tim (2005-09-30). "What Is Web 2.0? Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software".

- Milberry, K; Anderson, S. (2009). "Open Sourcing Our Way to an Online Commons: Contesting Corporate Impermeability in the New Media Ecology". Journal of Communication Inquiry. 33 (4): 393–412. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.475.4604. doi:10.1177/0196859909340349. S2CID 144027680.

- Gumpert, Gary; Robert Cathcart (1985). "Media grammars, generations, and media gaps". Critical Studies in Mass Communication. 2: 23–35. doi:10.1080/15295038509360059.

- Huntley, Rebecca (2006). The World According to Y: Inside the New Adult Generation. Australia: Crows Nest NSW. p. 17.

- Serazio, Michael. (New) Media Ecology and Generation Mash-Up Identity: The Technological Bias of Millennial Youth Culture. NCA 94th Annual Convention.

- Rushkoff, Douglas (2006). Screenagers: Lessons In Chaos From Digital Kids. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1572736245.

- D'Arcy, C. J.; Eastburn, D. M. & Bruce, B. C. (2009). "How Media Ecologies Can Address Diverse Student Needs". College Teaching. 57 (1): 56–63. doi:10.3200/CTCH.57.1.56-63. hdl:2142/9761. S2CID 144651734. ProQuest 274764053.

- Correa, Teresa; Hinsley, Amber Willard; de Zúñiga, Homero Gil (2010-03-01). "Who interacts on the Web?: The intersection of users' personality and social media use". Computers in Human Behavior. 26 (2): 247–253. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.09.003.

- Poell, Thomas (2014). "Social media and the transformation of activist communication: exploring the social media ecology of the 2010 Toronto G20 protests" (PDF). Information, Communication & Society. 17 (6): 716–731. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2013.812674. S2CID 145210419.

- Crandall, Heather; Cunningham, Carolyn M. (2016). "Media ecology and hashtag activism: #Kaleidoscope". Explorations in Media Ecology. 15 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1386/eme.15.1.21_1.

- Peterson, Mark Allen. "Egypt's media ecology in a time of revolution." Arab media & society 13 (2011).

- Beeman, William O. "The cultural role of the media in Iran: The revolution of 1978–1979 and after." The news media and national and international conflict (1984): 147–165.

- Bowman, Warigia. 2011. Dictators and the Internet. Cairo Review of Global Affairs. http://www.aucegypt.edu/GAPP/CairoReview/Pages/articleDetails.aspx?aid=34 [accessed November 14, 2013]

- Hoyng, Rolien; Es, Murat (2016). "Conspiratorial Webs: Media Ecology and Parallel Realities in Turkey". International Journal of Communication.

- Haciyakupoglu, Gulizar; Zhang, Weiyu (2015-03-18). "Social Media and Trust during the Gezi Protests in Turkey". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 20 (4): 450–466. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12121. ISSN 1083-6101.

- Treré, Emiliano; Mattoni, Alice (2015-11-25). "Media ecologies and protest movements: main perspectives and key lessons" (PDF). Information, Communication & Society. 19 (3): 290–306. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2015.1109699. ISSN 1369-118X. S2CID 146152044.

- Postill, John (2013-10-23). "Democracy in an age of viral reality: A media epidemiography of Spain's indignados movement". Ethnography. 15 (1): 51–69. doi:10.1177/1466138113502513. ISSN 1466-1381. S2CID 145666348.

References

- Fuller, Matthew (2005). Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- McLuhan, Marshall (1962). The Gutenberg Galaxy : the making of typographic man. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. pp. 293. ISBN 978-0-8020-6041-9.

- Postman, Neil (1985). Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. US: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-80454-2.

- Irimia R, Gottschling M (2016) Taxonomic revision of Rochefortia Sw. (Ehretiaceae, Boraginales). Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e7720. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.4.e7720. (n.d.). doi:10.3897/bdj.4.e7720.figure2f

External links

- Media Ecology Association

- Media Ecology reading list on the MEA website

- A First Look at Communication Theory, see McLuhan Chapter = Media Ecology of Marshall McLuhan/ by Em Griffin and E. J. Park