Technical communication

Technical communication is a means to convey scientific, engineering, or other technical information.[1] Individuals in a variety of contexts and with varied professional credentials engage in technical communication. Some individuals are designated as technical communicators or technical writers. These individuals use a set of methods to research, document, and present technical processes or products. Technical communicators may put the information they capture into paper documents, web pages, computer-based training, digitally stored text, audio, video, and other media. The Society for Technical Communication defines the field as any form of communication that focuses on technical or specialized topics, communicates specifically by using technology or provides instructions on how to do something.[2][3] More succinctly, the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communicators defines technical communication as factual communication, usually about products and services.[4] The European Association for Technical Communication briefly defines technical communication as "the process of defining, creating and delivering information products for the safe, efficient and effective use of products (technical systems, software, services)".[5]

Whatever the definition of technical communication, the overarching goal of the practice is to create easily accessible information for a specific audience.[6]

As a profession

Technical communicators generally tailor information to a specific audience, which may be subject matter experts, consumers, end users, etc. Technical communicators often work collaboratively to create deliverables that include online help, user manuals, classroom training guides, computer-based training, white papers, []s, industrial videos, reference cards, data sheets, journal articles, and patents. Technical domains can be of any kind, including the soft and hard sciences, high technology including computers and software and consumer electronics. Technical communicators often work with a range of specific Subject-matter experts (SMEs) on these educational projects.

Technical communication jobs include the following:[3] API writer, e-learning author, information architect, technical content developer, technical editor, technical illustrator, technical trainer, technical translator, technical writer, usability expert, user experience designer, and user interface designer. Other jobs available to technical communicators include digital strategist, marketing specialist, and content manager.

In 2015, the European Association for Technical Communication published a competence framework for the professional field of technical communication.[7]

Much like technology and the world economy, technical communication as a profession has evolved over the last half-century.[8][9] In a nutshell, technical communicators take the physiological research of a project and apply it to the communication process itself.

Content creation

Technical communication is a task performed by specialized employees or consultants. For example, a professional writer may work with a company to produce a user manual. Some companies give considerable technical communication responsibility to other technical professionals—such as programmers, engineers, and scientists. Often, a professional technical writer edits such work to bring it up to modern technical communication standards.

To begin the documentation process, technical communicators identify the audience and their information needs. The technical communicator researches and structures the content into a framework that can guide detailed development. As the body of information comes together, the technical communicator ensures that the intended audience can understand the content and retrieve the information they need. This process, known as the writing process, has been a central focus of writing theory since the 1970s, and some contemporary textbook authors apply it to technical communication. Technical communication is important to most professions, as a way to contain and organize information and maintain accuracy.

The technical writing process is based on Cicero's 5 canons of rhetoric, and can be divided into six steps:

- Determine purpose and audience

- Collect information (Invention)

- Organize and outline information (Arrangement)

- Write the first draft (Style)

- Revise and edit (Memory)

- Publish output (Delivery)

Determining purpose and audience

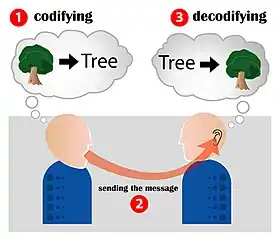

All technical communication serves a particular purpose—typically to communicate ideas and concepts to an audience, or instruct an audience in a particular task. Technical communication professionals use various techniques to understand the audience and, when possible, test content on the target audience. For example, if bank workers don't properly post deposits, a technical communicator would review existing instructional material (or lack thereof), interview bank workers to identify conceptual errors, interview subject matter experts to learn the correct procedures, author new material that instructs workers in the correct procedures, and test the new material on the bank workers.

Similarly, a sales manager who wonders which of two sites is better for a new store might ask a marketing professional to study the sites and write a report with recommendations. The marketing professional hands the report off to a technical communicator (in this case, a technical editor or technical writer), who edits, formats, and sometimes elaborates the document in order to make the marketing professional's expert assessment usable to the sales manager. The process is not one of knowledge transfer, but the accommodation of knowledge across fields of expertise and contexts of use. This is the basic definition of technical communication.

Audience type affects many aspects of communication, from word selection and graphics use to style and organization. Most often, to address a particular audience, a technical communicator must consider what qualities make a text useful (capable of supporting a meaningful task) and usable (capable of being used in service of that task). A non-technical audience might misunderstand or not even read a document that is heavy with jargon—while a technical audience might crave detail critical to their work such as vector notation. Busy audiences often don't have time to read entire documents, so content must be organized for ease of searching—for example by frequent headings, white space, and other cues that guide attention. Other requirements vary according to particular audience's needs.

Technical communicators may need to translate, globalize, or localize their documents to meet the needs of audiences in different linguistic and cultural markets. Globalization involves producing technical content that meets the needs of "as many audiences as possible," ideally an international audience.[10] Localization adapts existing technical content to fit the "cultural, rhetorical, educational, ethical, [and] legal" expectations of users in a specific local context.[10]

Technical communication in the government is particular and detailed. Depending on the segment of government (and country), the government component must follow distinct specifications. Information changes continuously and technical communications (technical manuals, interactive electronic technical manuals, technical bulletins, etc.) must be updated.

Collecting information

Technical communicators must collect all information that each document requires. They may collect information through primary (first-hand) research—or secondary research, using information from existing work by other authors. Technical communicators must acknowledge all sources they use to produce their work. To this end, technical communicators typically distinguish quotations, paraphrases, and summaries when taking notes.

Organizing and outlining information

Before writing the initial draft, the technical communicator organizes ideas in a way that makes the document flow well. Once each idea is organized, the writer organizes the document as a whole—accomplishing this task in various ways:

- chronological: used for documents that involve a linear process, such as a step-by-step guide that describes how to accomplish something;

- parts of an object: Used for documents that describe the parts of an object, such as a graphic showing the parts of a computer (keyboard, monitor, mouse, etc.);

- simple to complex (or vice versa): starts with easy ideas and gradually goes into complex ideas;

- specific to general: starts with many ideas, then organizes the ideas into sub-categories;

- general to specific: starts with a few categories of ideas, then goes deeper.

After organizing the whole document, the writer typically creates a final outline that shows the document structure. Outlines make the writing process easier and save the author time.

Writing the first draft

After the outline is complete, the writer begins the first draft, following the outline's structure. Setting aside blocks of an hour or more, in a place free of distractions, helps the writer maintain a flow. Most writers prefer to wait until the draft is complete before any revising so they don't break their flow. Typically, the writer should start with the easiest section, and write the summary only after the body is drafted.

The ABC (abstract, body, and conclusion) format can be used when writing a first draft of some document types. The abstract describes the subject, so that the reader knows what the document covers. The body is the majority of the document and covers topics in depth. Lastly, the conclusion section restates the document's main topics. The ABC format can also apply to individual paragraphs—beginning with a topic sentence that states the paragraph's topic, followed by the topic, and finally, a concluding sentence.

Revising and editing

Once the initial draft is laid out, editing and revising can be done to fine-tune the draft into a final copy. Usability testing can be helpful to evaluate how well the writing and/or design meets the needs of end users, and to suggest improvements [[11]] Four tasks transform the early draft into its final form, suggested by Pfeiffer and Boogard:

Adjusting and reorganizing content

In this step, the writer revises the draft to elaborate on topics that need more attention, shorten other sections—and relocate certain paragraphs, sentences, or entire topics.

Editing for style

Good style makes writing more interesting, appealing, and readable. In general, the personal writing style of the writer is not evident in technical writing. Modern technical writing style relies on attributes that contribute to clarity: headings, lists, graphics; generous white space, short sentences, present tense, simple nouns, active voice[12] (though some scientific applications still use the passive voice), second and third person as required

Technical writing as a discipline usually requires that a technical writer use a style guide. These guides may relate to a specific project, product, company, or brand. They ensure that technical writing reflects formatting, punctuation, and general stylistic standards that the audience expects. In the United States, many consider the Chicago Manual of Style the bible for general technical communication. Other style guides have their adherents, particularly for specific industries—such as the Microsoft Style Guide in some information technology settings.

Editing for grammar and punctuation

At this point, the writer performs a mechanical edit, checking the document for grammar, punctuation, common word confusions, passive voice, overly long sentences, etc.

References

- Johnson-Sheehan, Richard (2005). Technical Communication Today. Longman. ISBN 978-0-321-11764-9.

- Defining Technical Communication at the STC official website. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- What is Technical Communications? TechWhirl. Accessed December 9, 2014.

- Thinking of a career in technical communication? at the ISTC official website. Last updated May 2012. Accessed February 28, 2013.

- Defining Technical Communication at the tekom Europe official website. Last updated October 2015. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- What is Technical Communication? at the official website of the Technical Communicators Association of New Zealand. Accessed February 28, 2013.

- Competence Framework for Technical Communication at the tekom Europe official website. Last updated October 2015. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- E. A. Malone (December 2007). "Historical Studies of Technical Communication in the United States and England: A Fifteen-Year Retrospection and Guide to Resources". IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication. 50 (4): 333–351. doi:10.1109/TPC.2007.908732.

- Miles A. Kimball (April 2016). "The Golden Age of Technical Communication". Journal of Technical Writing and Communication. 47 (3): 330–358. doi:10.1177/0047281616641927.

- Batova, Tatiana; Clark, Dave (2014-12-09). "The Complexities of Globalized Content Management:". Journal of Business and Technical Communication. doi:10.1177/1050651914562472.

- Solving problems in technical communication. Johnson-Eilola, Johndan., Selber, Stuart A. Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-92406-9. OCLC 783150285.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Gary Blake and Robert W. Bly, The Elements of Technical Writing, pg. 63. New York: Macmillan Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0020130856