Milo (drink)

Milo (/ˈmaɪloʊ/; stylised as MILO) is a malted chocolate powder typically mixed with hot water or milk (or both) to produce a beverage.[1]

MILO's logo | |

| Type | Malted chocolate beverage |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Australia |

| Introduced | 1934 |

| Website | |

Milo was originally developed by Thomas Mayne and introduced at the 1934 Sydney Royal Easter Show.[2] It is produced by Nestlé.

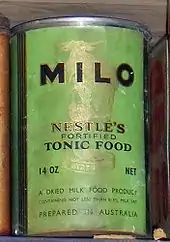

Most commonly sold as a powder in a green tin, often depicting various sporting activities, Milo is available as a premixed beverage in some countries, and has been subsequently developed into a snack bar, breakfast cereal and protein granola. Its composition and taste differ in some countries.

Milo maintains significant popularity in a diverse range of regions, including Oceania, South America, Southeast and East Asia, as well as Southern, East, and West Africa.[3][4][5]

Manufacturing

Milo is manufactured by evaporating the water content from a thick syrup at reduced pressure.[6] The thick opaque syrup is obtained from malted wheat or barley that is sourced from companies that produce these raw products.[7][8] Since 2017, Nestle in some regions has produced Milo using its "protomalt" formulation.[9][10] The protomalt is composed of carbohydrates derived from barley and cassava.[9][10]

Milo's composition and taste differ in some countries due to logistics limitations and personal preferences among different regions. For example, Milo in Japan has an almost identical taste to the one sold in Singapore, as the ingredients used were imported and manufactured from Singapore due to geographical proximity. Then, the powder is packaged at a factory in Kobe. In late 2020 when demand had significantly increased, the supply chain in both countries was temporarily disrupted, which were aggravated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[11][12][13]

History

In 1934, Australian industrial chemist and inventor Thomas Mayne developed Milo and launched it at the Sydney Royal Easter Show.[14] Milo began production at the plant located in Smithtown, near Kempsey on the North Coast of New South Wales. The name was derived from the famous ancient athlete Milo of Croton, after his legendary strength.[15]

Consumption

Traditionally in Australia and New Zealand, Milo is served mixed with either hot or cold milk, or sprinkled on top.[16]

Milo manufactured outside Australia is customised for local methods of preparation. In Malaysia as well as Brunei and some other parts of Asia, Milo with ice added is known as "Iced Milo" or "Milo Ais" in Malay Language (alternatively, "bing" or "peng", meaning ice in Cantonese and Hokkien respectively). Iced Milo is even available at fast food restaurants such as KFC and McDonald's.[17][18][19] Milo can be used as an ingredient in Roti canai, where it is usually called "Roti Milo".[20]

In Singapore, Milo is also served locally in hawker centres in versions such as "Milo dinosaur" (a cup of Milo with an extra spoonful of undissolved Milo powder added on top of it), "Milo Godzilla" (a cup of Milo with ice cream and/or topped with whipped cream) "Neslo" (combined with Nescafé powdered coffee). In Hong Kong, Milo is served in Cha chaan teng.[21]

Marketing

In Australia and most other countries, the packaging is green and depicts people playing various sports on the tin. A higher malt content form also existed in Australia and was marketed in a brown coloured tin which was usually only available in the 375g size. As of May 2015, this form is no longer manufactured.

In Australia, the MILO in2CRICKET and MILO T20 Blast programs, operated in most areas by volunteers, teach children age 5-12 how to play the game of cricket. In the 2016–2017 season, over 78,000 children participated in the programs.[22]

Milo's commercials and taglines are "Go and go and go with Milo". A recent Australian commercial incorporating this slogan depicts four generations of women on a skipping rope singing "and my mum gave me Milo to go and go and go." The tag "I need my Milo Today" is also used. The packaging of tins of Milo in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore are also green and also have people playing sports on the tins, giving it the affectionate name of "Tak Kiu", which is Hokkien Chinese for football. In Colombia, Milo is closely tied to football, and the slogan several generations have sung is Milo te da energía, la meta la pones tú ("Milo gives you the energy, you set the goal").

Milo is very popular in Asia, where the brand name is synonymous with chocolate flavoured drinks: Milo has a 90% market share in Malaysia (not the often quoted 90% worldwide share of Milo consumption),[23] and Malaysians were said to be the world's largest consumers of Milo.[24] This is because Milo was once used as a nutrient supplement when it was first introduced in the country, and has thus gained a reputation as a 'must have' drink for the old and the younger generations. Milo manufactured in Malaysia is made to dissolve well in hot water to produce a smooth hot chocolate drink, or with ice added for a cold drink. "Milo Vans" were often associated with sports days in these two countries, during which primary school pupils would queue up to collect their cups of Milo drinks using coupons.

In Peru, during the 1970s military dictatorship, Milo labels displayed Peruvian motifs, such as photos and pictures of Peruvian towns, history, crops, fruits, animals, plants,[25][26] as an educational aid. After 1980, when the military left power, sports predominated on the labels.

Milo is sold by Nestlé in Canada at all major food retailers. Although Milo has been available since the 1970s, a Canadian-specific flavour launched within the last decade that dissolves quicker but maintains the sweet malt flavour profile. It competes with the British brand Ovaltine.

Aside from the International section of specific grocery stores and certain Asian grocery stores, Nestlé does not market Milo in the United States. In 2017 the Colombian manufactured Milo has started appearing on shelves in supermarkets in the United States such as Walmart (Alongside Hispanic sections), and King Soopers (Denver CO).

It can also be found in the United Kingdom in some Sainsbury's and Tesco supermarkets, which import it from Kenya and South Africa. Asian food specialists, such as Mini Siam Oriental Foods and Hoo Hing also stock it. A similar product called Ovaltine is most popular with UK consumers.[27]

In China, it is commonly sold in Western supermarkets, but also smaller convenience stores. Usually packaged in a 240gram flexible foil pouch, single drink packets can also be purchased. The Milo itself contains more milk solids than the Australian Milo.[28]

In the past, it was available in Portugal and Brazil. Nestlé Brazil discontinued production of Milo in Brazil, to focus on the much-popular domestic brands Nescau and Nesquik. The Chilean version of Milo is still in production and is identical in taste and texture to the one that was once produced in Brazil.

In May 2013, and after more than 20 years out of the Portuguese market, Nestlé reintroduced the brand aiming at the high-end market.[29]

Nutritional information

Milo contains 1,680 kJ (402 calories) in every 100 g of the powder, mostly from carbohydrates. Carbohydrates can be used for energy by the body, which is the basis of Milo being marketed as an energy drink. Most of the carbohydrate content is sugar. The New Zealand version of Milo is 46 per cent sugar.[30]

Milo dissolved in water has a Glycemic Index (GI) of 55, lower than Coca-Cola's GI of 63.[31] However, milk has a much lower GI of 30 - 33, so mixing Milo into a mug of milk yields an overall GI closer to 33. [32]

The Milo website states that the drink is high in calcium, iron and the vitamins B1, B2, B6, B12. Milo is advertised as containing "Actigen-E", but this is just Nestlé's trademarked name for the vitamins in the Milo recipe.[33]

Milo contains some theobromine, a xanthine alkaloid similar to caffeine which is present in the cocoa used in the product.[34][35]

Derivative products

Milo is available as a snack in cube form, in Nigeria, Ghana and Dubai.[36]

Milo is available as Milo nuggets[37] and cereal balls in South East Asia and Colombia.[38][39]

In Australia, a new version of Milo called Milo B-Smart was released in 2008 (the original and malt Milo varieties remain); which is of a finer texture and has added B vitamins and iodine. It has a different taste from the original Milo formula and is marketed as a health food for children.[40]

References

- "Nestle's new Milo recipe tested by a dietitian". Stuff.co.nz. 13 July 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "History". Nestle.com.au. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "10 things you never knew about MILO". NewsComAu. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Nestle backs beverage 'belief' in Vietnam with $36m Milo investment". beveragedaily.com. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- migration (16 March 2015). "Milo under the spotlight after fake products seized in Malaysia: 10 facts about Milo". The Straits Times. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- Higman, B.W. (2011). How Food Made History. Wiley. p. 1889. ISBN 978-1-4443-4465-3. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Brewers' Society (London, England) (1963). Brewing Review. Brewing Publications. p. 416. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Lim, T.K. (2013). Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 5, Fruits. Edible Medicinal and Non-medicinal Plants. Springer Netherlands. p. 27. ISBN 978-94-007-5653-3. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Reuters Staff (2 August 2016). "Nestle invests $43 mln in new Milo chocolate drink plant". U.S. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Lacson, Nonoy E. (23 July 2017). "ARMM wants to supply Nestlé plant with cassava from Marawi and Lanao". Manila Bulletin News. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Guan Zhen Tan (8 December 2020). "Japan to stop selling Milo until March 2021 after viral tweet leads to high demand". mothership.sg. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- Ed (9 December 2020). "Japan suspends sale of Milo due to shortage of ingredients from Singapore". campus.sg. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- Mainichi Japan (9 December 2020). "Japan sales of Milo malt drink to be halted over difficulty obtaining imported ingredients". mainichi.jp. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- "About Milo". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- https://milo.com.au/all-about-milo

- "'Don't understand': Fitzy's surprise over Milo debate result". NewsComAu. 16 July 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- "Nutrition Information: Desserts & Beverages". Kentucky Fried Chicken. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- "Nutrition Information: Beverages". McDonald's. Archived from the original on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- Archived 19 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Food Tour Malaysia". Trip Advisor. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "Kong Sihk Tong | Eat the World NYC". www.eattheworldnyc.com. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "CRICKET AUSTRALIA AND MILO CELEBRATE 25 YEARS OF JUNIOR CRICKET". Nestle.

- "Nestlé: Our transformational opportunity". Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Jaya, Petaling (24 February 2009). "Shahrir urges restaurants to lower price of Milo". The Star Online. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- Arkivperu (5 August 2013). ""Zoología botánica" de Milo (1973) |". Arkivperu.com. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ""Zoología botánica" de Milo (1973)". Arkivperu. 2 December 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Fung, Lynn (12 January 2012). "A History of Malted Milk". Tatler Hong Kong. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- dairyreporter.com. "Milo minus the milk". dairyreporter.com. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Milo reintroduced". Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- "MILO® - MILO New Zealand". www.milo.co.nz. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- "Glycemic Index for Milo (Nestlé, Australia) dissolved in water". Diet & Fitness Today. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Shocking & Fun Facts You Should Know About Milo (Drink)". FoodsNG. 12 June 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "What is Actigen-E?". Milkpowder is too Danger. 22 July 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- "Caffeine and theobromine levels in selected Nigerian beverages". BioMedSearch. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- William Gervase Clarence-Smith (2000). Cocoa and Chocolate, 1765–1914. London: Routledge. pp. 10, 31. ISBN 0-415-21576-5.

- Company, Nestlé Alimentana (1975). Nestlé in the developing countries. Nestlé Alimentana S.A. pp. 100–101. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- https://www.nestle.com.my/brands/confectionery/milo_nuggets__choco_bar

- "MILO® Nuggets". Nestlé (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- https://eshop.tesco.com.my/groceries/en-GB/products/7000126020

- "Nestlé Urges Kids to B-Smart". Can and Aerosol News. 13 August 2008. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2016.