Moclips, Washington

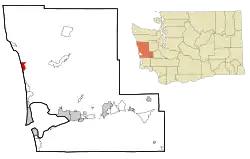

Moclips is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Grays Harbor County, Washington, United States. The population was 207 at the 2010 census.[1] It is located near the mouth of the Moclips River.

Moclips, Washington | |

|---|---|

Location of Moclips, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 47°14′10″N 124°12′46″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Grays Harbor |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.81 sq mi (4.69 km2) |

| • Land | 1.78 sq mi (4.62 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.07 km2) |

| Elevation | 43 ft (13 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 207 |

| • Density | 116/sq mi (44.8/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 98562 |

| Area code(s) | 360 |

| FIPS code | 53-46405[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512471[2] |

According to Edmond S. Meany, the word moclips comes from a Quinault word meaning a place where girls were sent as they were approaching puberty.[3] However, according to William Bright, the name comes from the Quinault word meaning simply "large stream".[4]

History

The indigenous inhabitants of the area were members of the Quinault tribe along the coast north of Grays Harbor and the Upper and Lower Chehalis tribes of the lower Chehalis River drainage. Other groups included the Copalis, Wynoochee, and Humptulips subtribes of the Upper Chehalis subtribe, and the Satsop subtribe of the Lower Chehalis. The Chehalis, Quinault, Cowlitz, and Queets spoke Coast Salish languages related to other Salishan language groups in the Northwest. The Quileute and Hoh spoke unrelated Chimakuan languages, while the Makah spoke a Wakashan language, also unrelated. To the south the Chinookan people spoke yet another family of unrelated languages, the Chinookan languages. All the tribes also used a trade pidgin called Chinook Jargon.

The area's indigenous people lived in permanent villages along rivers and lakes. Water defined their economic and cultural lives. They harvested salmon as they swam upstream to spawn, as well as whales and seals along the coast. In the summers, hunters ranged inland and into the Olympic Mountains for game and to trade with other tribal groups. The Indians developed a high degree of skill with canoes carved from cedar trees in a variety of specialized designs adapted to swift-flowing rivers, broad estuaries, and the sea.

The Quinaults' first recorded contact with Europeans, in 1775 near Grenville Point, ended in the deaths of seven Spaniards and as many as seven Indians. The Indians had traded peacefully with the explorers, but turned on them after the Spaniards landed, erected a cross, and claimed the land for the Spanish king. The reason for the sudden attack remains unexplained, but tribal historians have offered the possibility that the Europeans had violated a woman's safe haven.

In 1792, Captain Robert Gray discovered Grays Harbor and entered the Columbia River, the first non-indigenous people to have done so. In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson sent the Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore the vast interior between the Missouri River and the Pacific Ocean. Although the expedition cemented American claims to Oregon Country, it failed to find a practical wagon route. It wasn't until the Oregon Trail began to be used by American settlers in the 1840s that British control of the Pacific Northwest, in the form of the Hudson's Bay Company, became challenged.

Contact with Europeans and the frequent interaction between tribes accelerated the several epidemics that swept the region, beginning with smallpox in the 1770s and continuing with what was likely malaria in 1829, cholera in 1836, and smallpox again in 1853. The native population dropped from thousands to a few dozen. So many Chinooks died around Willapa Bay in the 1850s that the Chehalis moved in to take their place.

In 1855, after the creation of Washington Territory, the Quinault Treaty was signed by Chief Taholah of the Quinault and Chief How-yat'l of the Quileute, along with many other tribal delegates. One result of the treaty was the creation of the roughly triangular shaped Quinault Indian Reservation between the Pacific Ocean and Lake Quinault.

The first American settlers came to the North Beach area in the mid-19th century. Many homesteaded with 160 acres (0.65 km2) of fine timber.

Although settled earlier by homesteaders such as Steve Grover in 1862, Moclips was not incorporated until 1905 with the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway and the first Moclips Beach Hotel built by Dr. Edward Lycan. The hotel was a two-story, 150-room beachside resort. It burned down in 1905, just months after it was completed. Dr. Lycan then had a new, larger hotel built on the same site. It was three stories high, a block long, and loomed from the dunes. This Moclips Beach Hotel was completed in 1907 and advertised as having 270 "outside" rooms, with 2,000 feet (610 m) of 10-foot (3.0 m) covered veranda, and a perfect view of the Pacific Ocean, reported to be just 12 feet (3.7 m) from the hotel grounds. This close proximity to the ocean, however, would prove its undoing.

Back then Moclips was publicized as a healthy getaway from the toil and trouble of city life. It was a health resort. The moist salt air and bathing in the surf was touted as very medicinal. A promotional pamphlet of the time purports Moclips' climate to be "simply perfect". Dr. Lycan believed that Moclips was the Mecca for health and pleasure of the Northwest.

Moclips grew into a sizable town with restaurants, hotels, a candy store, theater, canneries, and the M.R. Smith Lumber and Shingle Mill. Many hotels, schools, canneries and shingle mills were quickly built. Four schools once taught children from Taholah to Ocean Shores. Class schedules for the local schools were based on the clamming tides. Two of these buildings exist today.

.jpeg.webp)

In 1911 Moclips was struck by a series of fatal storms, eventually washing much of the town away. The Moclips Beach Hotel stood in pieces.[5] By the end of 1913, there was nothing left of the hotel. Fires destroyed much of Moclips along the beach. In 1948 a hilltop welding accident destroyed many homes and businesses.

The U.S. Navy and Air Force made the neighboring town of Pacific Beach their home during World War II. The Navy still occupies property along the bluff in Pacific Beach - now a recreational use center for the military.

In 1960, a second wave of tourism began. According to yearly polls by Evening magazine, this resort town is consistently near the top of places to visit in Washington state, being number two behind Seattle.

Geography

Moclips is located in western Grays County at 47°13′11″N 124°12′17″W (47.219809, -124.204838).[6] The CDP includes the community of Moclips, plus the residential area of Sunset Beach. The CDP is bordered to the south by Pacific Beach, to the north by the Quinault Indian Reservation, and to the west by the Pacific Ocean.

Washington State Route 109 passes through Moclips, leading north 9 miles (14 km) along the Pacific coast to its terminus at Taholah and southeast 31 miles (50 km) to Hoquiam.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 1.81 square miles (4.69 km2), of which 1.78 square miles (4.62 km2) are land and 0.03 square miles (0.07 km2), or 1.48%, are water.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 2000 | 615 | — | |

| 2010 | 207 | −66.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

As of the 2000 census, the Moclips CDP included the area of Pacific Beach, which was split before the 2010 census to form its own CDP.

As of the census[7] of 2000, there were 615 people, 273 households, and 146 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 189.1 people per square mile (73.1/km2). There were 565 housing units at an average density of 173.7/sq mi (67.1/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 64.72% White, 0.16% African American, 24.72% Native American, 0.81% Asian, 0.49% Pacific Islander, 2.44% from other races, and 6.67% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.15% of the population.

There were 273 households, out of which 17.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.6% were married couples living together, 11.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.5% were non-families. 36.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.25 and the average family size was 2.90.

In the CDP, the population was spread out, with 21.0% under the age of 18, 6.5% from 18 to 24, 25.0% from 25 to 44, 31.9% from 45 to 64, and 15.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 44 years. For every 100 females, there were 109.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 106.8 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $27,500, and the median income for a family was $32,045. Males had a median income of $31,250 versus $21,250 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $17,411. About 8.1% of families and 9.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.3% of those under age 18 and 5.5% of those age 65 or over.

Popular culture

The beach scenes of the 1974 John Wayne film McQ were filmed at Moclips.

The song "NW Apt." by Seattle-based rock band Band of Horses takes place in Moclips.[8]

The 2012 Animal Planet science docufiction television film Mermaids: The Body Found is about two former National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration scientists who uncover the source behind mysterious underwater recordings and an unidentified marine body during an investigation of mass stranding of whales in Moclips.

According to Michael Azzerad, Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain and his band Fecal Matter opened for The Melvins at a Moclips beach bar called The Spot Tavern.[9]

References

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Moclips CDP, Washington". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- "Moclips". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- Meany, Edmond S. (1920). "Origin of Washington Geographic Names". The Washington Historical Quarterly. Washington University State Historical Society. XI: 207. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- Bright, William (2007). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4.

- "Moclips, WA Storm Washes Half of the Town Away, Feb 1911". Seattle Daily Times, Seattle. 15 February 1911. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Music video, with Moclips referenced at 00:29/03:01". Archived from the original on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- Azerrad, Michael (1994). Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Doubleday. p. 38. ISBN 9780385471992.