Mu (mythical lost continent)

Mu is a legendary lost continent. The term was introduced by Augustus Le Plongeon, who used the "Land of Mu" as an alternative name for Atlantis. It was subsequently popularized as an alternative term for the hypothetical land of Lemuria by James Churchward, who asserted that Mu was located in the Pacific Ocean before its destruction.[1] Archaeologists assign assertions about Mu to the category of pseudoarchaeology. The place of Mu in literature has been discussed in detail in Lost Continents (1954) by L. Sprague de Camp.

| Mu | |

|---|---|

| 'Lost Continent of Mu Motherland of Men' location | |

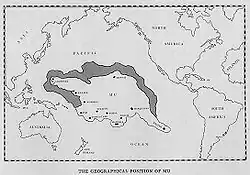

Map of Mu by James Churchward | |

| Created by | Augustus Le Plongeon |

| Genre | Pseudoscience |

| Information | |

| Type | Hypothetical lost continent |

Geologists dismiss the existence of Mu and the lost continent of Atlantis as physically impossible, arguing that a continent can neither sink nor be destroyed in the short period of time asserted in legends and folklore and literature about these places.[2][3] Mu's existence is considered to have no factual basis.[4][5]

History of the concept

Augustus Le Plongeon

The mythical idea of the "Land of Mu" first appeared in the works of the British-American antiquarian Augustus Le Plongeon (1825–1908), after his investigations of the Maya ruins in Yucatán.[6] He claimed that he had translated the first copies of the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the K'iche' from the ancient Mayan using Spanish.[7] He claimed the civilization of Yucatán was older than those of Greece and Egypt, and told the story of an even older continent.

Le Plongeon got the name "Mu" from Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, who, in 1864, mistranslated what was then called the Troano Codex (now called "Madrid Codex") using the de Landa alphabet. Brasseur believed that a word which he read as Mu referred to a land that had been submerged by a catastrophe.[8] Le Plongeon identified this lost land with Atlantis and, following Ignatius Donnelly in Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882), identified it as a continent that had once existed in the Atlantic Ocean:

In our journey westward across the Atlantic we shall pass in sight of that spot where once existed the pride and life of the ocean, the Land of Mu, which, at the epoch that we have been considering, had not yet been visited by the wrath of Human, that lord of volcanic fires to whose fury it afterward fell a victim. The description of that land given to Solon by Sonchis, priest at Sais; its destruction by earthquakes, and submergence, recorded by Plato in his Timaeus, have been told and retold so many times that it is useless to encumber these pages with a repetition of it.[6]:ch. VI, p. 66

Le Plongeon claimed that the civilization of ancient Egypt was founded by Queen Moo, a refugee from the land's demise. Other refugees supposedly fled to Central America and became the Maya.[3]

James Churchward

Mu, as an alternative name for a lost Pacific Ocean continent previously identified as the hypothetical Lemuria (the supposed place of origin for lemurs), was later popularised by James Churchward (1851–1936) in a series of books, beginning with Lost Continent of Mu, the Motherland of Man (1926),[1] re-edited later as The Lost Continent Mu (1931).[9] Other popular books in the series are The Children of Mu (1931) and The Sacred Symbols of Mu (1933).

Churchward claimed that "more than fifty years ago", while he was a soldier in India, he befriended a high-ranking temple priest who showed him a set of ancient "sunburnt" clay tablets, supposedly in a long-lost "Naga-Maya language" which only two other people in India could read. Churchward convinced the priest to teach him the dead language and decipher the tablets by promising to restore and store the tablets, for Churchward was an expert in preserving ancient artifacts. The tablets were written in either Burma or in the lost continent of Mu itself, according to the high priest.[10] Having mastered the language himself, Churchward found out that they originated from "the place where [man] first appeared—Mu". The 1931 edition states that "all matter of science in this work are based on translations of two sets of ancient tablets": the clay tablets he read in India, and a collection of 2,500 stone tablets that had been uncovered by William Niven in Mexico.[9]:7

The tablets begin with the creation of Earth, Mu, and the superior human civilization Naacal by the seven commands of the seven superlative intellects of the seven-headed serpent Narayana. This creation story dismisses the theory of evolution.[10] Churchward gave a vivid description of Mu as the home of an advanced civilization, the Naacal, which flourished between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago, was dominated by a “white race",[9]:48 and was "superior in many respects to our own".[9]:17 At the time of its demise, about 12,000 years ago, Mu had 64 million inhabitants and seven major cities, and colonies on the other continents. The 64 million inhabitants were separated as ten tribes that followed one government and one religion.

Churchward claimed that the landmass of Mu was located in the Pacific Ocean, and stretched east–west from the Marianas to Easter Island, and north–south from Hawaii to Mangaia. According to Churchward the continent was supposedly 5,000 miles from east to west and over 3,000 miles from north to south, which is larger than South America. The continent was believed to be flat with massive plains, vast rivers, rolling hills, large bays, and estuaries.[11] He claimed that according to the creation myth he read in the Indian tablets, Mu had been lifted above sea level by the expansion of underground volcanic gases. Eventually Mu "was completely obliterated in almost a single night":[9]:44 after a series of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, "the broken land fell into that great abyss of fire" and was covered by "fifty millions of square miles of water."[9]:50 Churchward claimed the reasoning for the continent's destruction in one night was because the main mineral on the island was granite and was honeycombed to create huge shallow chambers and cavities filled with highly explosive gases. Once the chambers were empty after the explosion, they collapsed on themselves, causing the island to crumble and sink.[12]

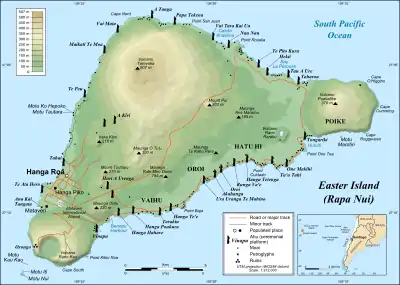

Churchward claimed that Mu was the common origin of the great civilizations of Egypt, Greece, Central America, India, Burma and others, including Easter Island, and was in particular the source of ancient megalithic architecture. As evidence for his claims, he pointed to symbols from throughout the world, in which he saw common themes of birds, the relation of the Earth and the sky, and especially the Sun. Churchward claimed that the king of Mu was named Ra and he related this to the Egyptian god of the sun, Ra, and the Rapa Nui word for Sun, ra’a.[9]:48 He claimed to have found symbols of the Sun in "Egypt, Babylonia, Peru and all ancient lands and countries – it was a universal symbol."[9]:138

As additional evidence for his claims, Churchward looked to the Holy Bible and found through his own translations that Moses was trained by the Naacal brotherhood in Egypt. Assyria mistranslated when writing and misplaced the Garden of Eden, which according to Churchward would have been located in the Pacific Ocean.

Churchward makes references to the Ramayana epic, a religious text of Hindu attributed to sage and historian Valmiki. Valmiki mentions the Naacals as “coming to Burma from the land of their birth in the East,” that is, in the direction of the Pacific Ocean.[13]

Churchward attributed all megalithic art in Polynesia to the people of Mu. He claimed that symbols of the sun are found "depicted on stones of Polynesian ruins", such as the stone hats (pukao) on top of the giant moai statues of Easter Island. Citing W. J. Johnson, Churchward describes the cylindrical hats as "spheres" that "seem to show red in the distance", and asserts that they “represent the Sun as Ra.”[9]:138 He also incorrectly claimed that some of them are made of "red sandstone",[9]:89 which does not exist on the island. The platforms on which the statues rest (ahu) are described by Churchward as being "platform-like accumulations of cut and dressed stone", which were supposedly left in their current positions "awaiting shipment to some other part of the continent for the building of temples and palaces".[9]:89 He also cites the pillars "erected by the Māori of New Zealand" as an example of this lost civilization's handiwork.[9]:158 In Churchward's view, the present-day Polynesians are not descendants of the dominant members of the lost civilization of Mu, responsible for these great works, but are instead descendants of survivors of the cataclysm that adopted "the first cannibalism and savagery" in the world.[9]:54

The lost continent of Mu, according to Jack E. Churchward, is different from the continent of Lemuria that is theorized to be in the Pacific or Indian Ocean. In his novels, Churchward never mentions the supposed other lost continent of Lemuria. Lemuria is imagined to be slightly larger than Mu when located in the Pacific, but otherwise most people generally consider them the same mythological continent that once existed in the Pacific Ocean.[14]

John Newbrough

In the 1882 novel Oahspe: A New Bible, John Newbrough included a map of the Earth in antediluvian times (i.e. prior to the great flood of biblical record) where an unknown continent is located in the Northern Pacific. Newbrough called this continent Pan. People often link both Pan and Mu as the same mythological continent since both are claimed to be located in the Pacific. Newbrough continues to claim that the unknown continent disappeared 24,000 years ago, but will soon rise from the Pacific and will be inhabited by the Kosmon race.[15]

Max Heindel

Max Heindel, a Danish-American occultist, wrote about Mu in The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception (1909), which offers a different image and chronology. According to Heindel, Mu existed when the Earth's crust was still hardening, in a period of high heat and dense atmosphere. Heindel claims humans existed at this time, but that they had the power to shape-shift. He says they had no eyes but rather two sensitive spots that were affected by the light of the Sun. In the dense atmosphere, humans were guided more by internal perception than by external vision. The language of these humans consisted of the sounds of nature.[16]

Louis Jacolliot

Louis Jacolliot was a French attorney, judge, and occultist who specialized in the translation of Sanskrit. He wrote about the land of the Rutas, a lost land that ancient sources claimed was in the Indian Ocean but which he placed in the Pacific Ocean and associated with Atlantis stories in Histoire des Vierges. Les Peuples et les continents disparus (1874). He amplified upon this in Occult Science in India (1875, English translation 1884). He has been identified as a contributor to Rosicrucianism.[17]

Modern claims

James Bramwell and William Scott-Elliot claimed that the cataclysmic events on Mu began 800,000 years ago[18]:194 and went on until the last catastrophe, which occurred in precisely 9564 BC.[18]:195

In the 1930s, Atatürk, founder of the Turkish Republic, was interested in Churchward's work and considered Mu as a possible location of the original homeland of the Turks.[19]

Masaaki Kimura has suggested that certain underwater features located off the coast of Yonaguni Island, Japan (popularly known as the Yonaguni Monument), are ruins of Mu.[20][21]

Criticisms

Geological arguments

Modern geological knowledge rules out "lost continents" of any significant size. According to the theory of plate tectonics, which has been extensively confirmed since the 1970s, the Earth's crust consists of lighter "sial" rocks (continental crust rich in aluminium silicates) that float on heavier "sima" rocks (oceanic crust richer in magnesium silicates). The sial is generally absent in the ocean floor where the crust is a few kilometers thick, while the continents are huge solid blocks tens of kilometers thick. Since continents float on the sima much like icebergs float on water, a continent cannot simply "sink" under the ocean.

It is true that continental drift and seafloor spreading can change the shape and position of continents and occasionally break a continent into two or more pieces (as happened to Pangaea). However, these are very slow processes that occur in geological time scales (hundreds of millions of years). Over the scale of history (tens of thousands of years), the sima under the continental crust can be considered solid, and the continents are basically anchored on it. It is almost certain that the continents and ocean floors have retained their present position and shape for the whole span of human existence.

There is also no conceivable event that could have "destroyed" a continent, since its huge mass of sial rocks would have to end up somewhere—and there is no trace of it at the bottom of the oceans. The Pacific Ocean islands are not part of a submerged landmass but rather the tips of isolated volcanoes.

This is the case, in particular, of Easter Island, which is a recent volcanic peak surrounded by deep ocean (3,000 m deep at 30 km off the island). After visiting the island in the 1930s, Alfred Métraux observed that the moai platforms are concentrated along the current coast of the island, which implies that the island's shape has changed little since they were built. Moreover, the "Triumphal Road" that Pierre Loti had reported ran from the island to the submerged lands below, is actually a natural lava flow.[22] Furthermore, while Churchward was correct in his claim that the island has no sandstone or sedimentary rocks, the point is irrelevant because the pukao are all made of native volcanic scoria.

Archaeological evidence

After the Pleistocene, cultures of the Americas and the Old World developed social complexity independent of each other,[23]:62 and, in fact, agriculture and sedentism emerged in multiple locations around the world after the inception of the Holocene at 11,700 BP. The emergence of Pre-Pottery Neolithic A sites such as Göbekli Tepe and Neolithic villages such as Jericho and Çatalhöyük in the Levant and Anatolia, respectively, result from local processes of cultural evolution, not colonization by individuals from elsewhere.

Easter Island was first settled around AD 300[24] and the pukao on the moai are regarded as having ceremonial or traditional headdresses.[24][25]

In popular culture

Film/television

- In the 1935 movie The Phantom Empire, the inhabitants of Murania are the lost tribe of Mu.

- In the 1963 movie Atragon, Mu is an undersea kingdom.

- In the 1970 kaiju film Gamera vs. Jiger, Jiger originates from the lost continent of Mu.

- In the 1982–1983 French-Japanese animated series The Mysterious Cities of Gold, Tao is the last living descendant of the sunken empire of Mu (Hiva in the English dub).

- In the 1983 Doraemon film Doraemon: Nobita and the Castle of the Undersea Devil, Doraemon and friends meet a young boy from Mu who is an undersea person and a soldier of Federal Army of Mu. They set out into the Bermuda Triangle to stop the army inside the lost city of Atlantis.

- In the 1983–1984 anime Super Dimension Century Orguss, the main antagonists are robots that were built by the ancient civilization of the Mu that turned on their creators and tried to annihilate all remaining life on Earth. Throughout the series, the robots are referred to as the Mu.

- In the 2001–2002 anime RahXephon the inhabitants of Mu, which are referred to as Mulians, serve as the show's primary antagonists.

Literature/print

- H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937) featured the lost continent in his revision of Hazel Heald's short story "Out of the Aeons" (1935).[26] Mu appears in numerous Cthulhu mythos stories, including many written by Lin Carter.[27]

- In Marvel Comics, the continents of Mu and Atlantis were destroyed by the Celestials. Their evacuation was aided by the Eternals.

- In Fredric Brown's short story "Letter to a Phoenix" (1949), the 180,000 year old narrator lists the six human civilizations he saw fall during his lifetime. Mu is the fifth of them (the last one being Atlantis).

- The 1967 Andre Norton novel Operation Time Search features a modern-day protagonist cast back in time, where he participates in a war between Atlantis and Mu.

- The 1970 Mu Revealed is a humorous spoof[28] by Raymond Buckland purporting to describe the long lost civilization of Muror, located on the legendary lost continent of Mu. The book was written under the pseudonym "Tony Earll", an anagram of "not really". The book claimed to present a translation of a diary compiled by a boy called Kland found and translated by an archaeologist named "Reedson Hurdlop", an anagram of "Rudolph Rednose".[29]

- "The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu", a fictional secret society in Eye in the Pyramid, the first book in the 1975 trilogy The Illuminatus! Trilogy by Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea

- Tom Robbins' novel Still Life with Woodpecker (1980) makes extensive reference to Mu.

- Alison Bailey Kennedy, an Editor-in-Chief of the cyberculture magazine Mondo 2000, published under the pseudonym of Queen Mu.

- In the manga version of Shaman King (1998–2004) the final rounds of the Shaman Tournament, as well as the Great Spirit ceremony, are held on the island (which is submerged and hidden by Patch Tribe rituals).

- The continent figures into the 2009 novel Inherent Vice by Thomas Pynchon.

- Mu features prominently in two Corto Maltese adventures - Under the Sign of Capricorn and Mu, The Last Continent

Music

- Robert Plant, of Led Zeppelin, used the feather symbol of Mu on the sleeve of Led Zeppelin IV.

- The rock band MU (1971–1974), created by American rock guitar musicians Jeff Cotton and Merrell Wayne Fankhauser, took its name from the book The Lost Continent Mu (1931).

- The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu, an early name of the British pop music group KLF active between 1987 and 1992.

- Mu Empire is the name of the second track on Long Island post-hardcore band Glassjaw's second studio album, Worship and Tribute.

Video games

- The SquareSoft (later Square Enix) video game released in Japanese markets as SaGa 3 (1991) and in the United States as Final Fantasy Legend III (1993) features a town known as Muu and situated on land flooded between the game's Past and (second) Present time phases.

- In Dragon Quest 3, produced by Enix (later Square Enix), the main character comes from a large continent in the pacific ocean called "Aliahan". Given that the land masses of this world share similar appearance and names to those on earth, this starting continent could very well be the lost continent of Mu.

- One of the levels in the 1993 DuckTales 2 videogame is set on the island of Mu.[30]

- In Illusion of Gaia from 1993, Mu is one of the ancient ruin sites visited by player character Will, modeled in part on Easter Island. Like the real-world island, the Muian civilization fell due to a collapse of all natural resources, though some escaped via an underwater tunnel to found the Village of Angels while those left behind were mutated into the monsters on Mu by the Chaos Comet. When Will arrives there, Mu is a cursed land controlled by vampires.

- In Terranigma, the third game in the unofficial Quintet trilogy, alongside Soul Blazer and Illusion of Gaia, both Mu and Polynese are secret continents that may be resurrected towards the end of the first chapter of the game, once the main continents have been resurrected.

- The 1996 RPG Star Ocean features an alien race known as the Muah who originated from the lost continent on Earth.

- MU Online is a 2003 3D fantasy MMORPG developed in Korea and popular there, "based on the legendary Continent of MU".[31]

- In the 2004 video game City of Heroes, Mu was a patron land of one of the ancient pantheons who opposed the Orenbegans, a civilization of magic users under the protection of a rival goddess. These civilisations destroyed each other in war, but descendants of the Mu were found and forced into service to the modern criminal organisation, Arachnos.

- Mega Man Star Force 2 from 2007 features a whole story of Mu, the lost FM technology that past civilizations built was found here.

- The Evil Within 2's character Father Theodore Wallace is leader of the Mu Center in the fictional town of Krimson. He can be found in a simulated idyllic town called Union which he tries to overtake as cult leader by worship of the flame.

- Used as the chat group nickname for the best players in the history of Golf Rival, an app for frivolous spenders who think that the ability to multiply and divide by 3 makes them special

- In the 2016 game Sid Meier's Civilization VI, Mu is used as one of the names of the continents generated by the game.

See also

References

- Churchward, James (1926). Lost Continent of Mu, the Motherland of Man. United States: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-4680-4.

- Haugton, Brian (2007). Hidden History. New Page Books. ISBN 978-1-56414-897-1. Page 60.

- De Camp, Lyon Sprague (1971) [1954]. Lost Continents: Atlantis Theme in History, Science and Literature. Dover Publications. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-486-22668-2.

- Brennan, Louis A. (1959). No Stone Unturned: An Almanac of North American Pre-history. Random House. Page 228.

- Witzel, Michael (2006). Garrett G. Fagan Routledge (ed.). Archaeological Fantasies. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30593-8. Page 220.

- Le Plongeon, Augustus (1896). Queen Móo & The Egyptian Sphinx. The Author. pp. 277 pages.

- Card J. Jeb (2018). Spooky Archaeology, Myth and the Science of the Past. University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque pg. 130

- John Sladek, The New Apocrypha (New York: Stein and day, 1974) 65–66.

- Churchward, James (1931). The Lost Continent of Mu. New York: Ives Washburn. Re-published by Adventures Unlimited Press (2007)

- Churchward, James (1926). Lost Continent of Mu, the Motherland of Man. United States: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-4680-4.

- Churchward, James (1926). Lost Continent of Mu, the Motherland of Man. United States: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-4680-4

- Churchward, James (1926). Lost Continent of Mu, the Motherland of Man. United States: Kessinger Publishing.ISBN 0-7661-4680-4

- "The Lost Continent Of Mu | Unariun Wisdom".

- "Podcast #34 What's the difference between Lemuria and Mu?" – via www.youtube.com.

- Camp De Sprague L. (1970). Lost Continents, The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature p. 70–71. Dover Publications, Inc: New York

- Wauchope Robert (1962). Lost Tribes and Sunken Continents: Myth and Method In The Study Of American Indians, pp. 42–43. University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London.

- Camp De Sprague L. (1970). Lost Continents, The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature, p. 70. Dover Publications, Inc: New York

- Bramwell, James (1939). Lost Atlantis.

- Kayıp Kıta Mu, presentation, Ege-Meta Yayınları, İzmir, 2000, ISBN 975-7089-20-6

- Kimura, Masaaki (1991). Mu tairiku wa Ryukyu ni atta (The Continent of Mu was in Ryukyu) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten.

- Schoch, Robert M. "Ancient underwater pyramid structure off the coast of Yonaguni-jima".

- Metraux, Alfred. Mysteries of Easter Island (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-06.

- Abramyan, Evgeny (2009). Civilization in the 21st Century (PDF). Russia: How to Save the Future?. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-18.

- Danver, Steven L. (22 December 2010). Popular controversies in world history : investigating history's intriguing questions. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-077-3.;:222

- "The Ryukyuanist" (PDF). The Ryukyuanist (57). Autumn 2002. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. and Hazel Heald. "Out of the Aeons" (1935) in The Horror in the Museum and Other Revisions, S. T. Joshi (ed.), 1989. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-87054-040-8.

- Harms, Daniel. "Mu" in The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana (2nd ed.), pp. 200–202. Chaosium, Inc., 1998. ISBN 1-56882-119-0.

- Melton, J. Gordon (1999). Religious leaders of America: a biographical guide to founders and leaders of religious bodies, churches, and spiritual groups in North America. Gale Research. p. 91. ISBN 9780810388789. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Nield, Ted (2007). Supercontinent: Ten Billion Years in the Life of Our Planet. Harvard University Press. p. 56-57. ISBN 9780674026599. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Duck Tales 2". Retroplay. 1993. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- "MU Online | Medieval Fantasy MMORPG". MU Online English Official Site.