Göbekli Tepe

Göbekli Tepe (Turkish: [gœbecˈli teˈpe],[1] "Potbelly Hill"),[2] also known as Girê Mirazan or Xirabreşkê (Kurdish),[3] is an archaeological site in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey approximately 15 km (9 mi) as the crow flies or 30 km (19 mi) by car, northeast of the city of Şanlıurfa.[4] The tell (artificial mound) has a height of 15 m (50 ft) and is about 300 m (1,000 ft) in diameter.[5] It is approximately 760 m (2,500 ft) above sea level.

Girê Mirazan Xirabreşkê | |

The ruins of Göbekli Tepe | |

Shown within Turkey  Göbekli Tepe (Near East)  Göbekli Tepe (Eastern Mediterranean) | |

| Location | Örencik, Şanlıurfa Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°13′23″N 38°55′21″E |

| Type | Sanctuary |

| History | |

| Founded | Pre-10th millennium BCE |

| Abandoned | 8th millennium BCE |

| Periods | Pre-Pottery Neolithic A to B |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Well preserved |

| Official name | Göbekli Tepe |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | (i), (ii), (iv) |

| Designated | 2018 (42nd session) |

| Reference no. | 1572 |

| State party | Turkey |

| Region | Western Asia |

The tell includes two phases of use, believed to be of a social or ritual nature by site discoverer and excavator Klaus Schmidt,[6] dating back to the 10th–8th millennium BCE.[7] During the first phase, belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), circles of massive T-shaped stone pillars were erected—the world's oldest known megaliths.[8]

More than 200 pillars in about 20 circles are known (as of May 2020) through geophysical surveys. Each pillar has a height of up to 6 m (20 ft) and weighs up to 10 tons. They are fitted into sockets that were hewn out of the local bedrock.[9] In the second phase, belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), the erected pillars are smaller and stood in rectangular rooms with floors of polished lime. The site was abandoned after the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB). Younger structures date to classical times.

The details of the structure's function remain a mystery. The excavations have been ongoing since 1996 by the German Archaeological Institute, but large parts still remain unexcavated. In 2018, the site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[10]

Chronological context

While the site formally belongs to the earliest Neolithic (PPNA), to date no traces of domesticated plants or animals have been found. The inhabitants are presumed to have been hunters and gatherers who nevertheless lived in villages for at least part of the year.[11] So far, very little evidence for residential use has been found. Through the radiocarbon method, the end of Layer III can be fixed at about 9000 BCE (see above), but it is hypothesized by some archaeologists that the elevated location may have functioned as a spiritual center during 10,000 BCE or earlier, essentially, at the very end of the Pleistocene.

Archaeologists estimate that up to 500 persons were required to extract the heavy pillars from local quarries and move them 100–500 meters (330–1,640 ft) to the site.[12] The pillars weigh 10–20 metric tons (10–20 long tons; 11–22 short tons), with one still in the quarry weighing 50 tons.[13]

Around the beginning of the 8th millennium BCE Göbekli Tepe lost its importance. The advent of agriculture and animal husbandry brought new realities to human life in the area, and the "Stone-age zoo" (Schmidt's phrase applied particularly to Layer III, Enclosure D) apparently lost whatever significance it had had for the region's older, foraging communities. However, the complex was not simply abandoned and forgotten to be gradually destroyed by the elements. Instead, each enclosure was deliberately buried under as much as 300 to 500 cubic meters (390 to 650 cu yd) of refuse, creating a tell consisting mainly of small limestone fragments, stone vessels, and stone tools. Many animal and even human bones have been identified in the fill.[14]

Discovery and research history

.JPG.webp)

The site was first noted in a survey conducted by Istanbul University and the University of Chicago in 1963.[15] American archaeologist Peter Benedict identified lithics collected from the surface of the site as belonging to the Aceramic Neolithic,[16] but mistook stone slabs (the upper parts of the T-shaped pillars) for grave markers, postulating that the prehistoric phase was overlain by a Byzantine cemetery.[17][18] The hill had long been under agricultural cultivation, and generations of local inhabitants had frequently moved rocks and placed them in clearance piles, which may have disturbed the upper layers of the site. At some point attempts had been made to break up some of the pillars, presumably by farmers who mistook them for ordinary large rocks.[6]

In 1994, German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt, who had previously been working at Nevalı Çori, was looking for another site to excavate. He reviewed the archaeological literature on the surrounding area, found the 1963 Chicago researchers' brief description of Göbekli Tepe, and decided to reexamine the site. Having found similar structures at Nevalı Çori, he recognized the possibility that the rocks and slabs were prehistoric. He began excavations the following year and soon unearthed the first of the huge T-shaped pillars.[6] Schmidt continued to direct excavations at the site on behalf of the Şanlıurfa Museum and the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) until his death in 2014. Since then, the DAI's research at the site has been coordinated by Lee Clare.[10] Recent excavations have been more limited than Schmidt's, focusing on detailed documentation and conservation of the areas already exposed.[19]

Dating

The imposing stratigraphy of Göbekli Tepe attests to many centuries of activity, beginning at least as early as the Epipaleolithic period. Structures identified with the succeeding period, Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), have been dated to the 10th millennium BCE.[20] Remains of smaller buildings identified as Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) and dating from the 9th millennium BCE have also been unearthed.[7]

A number of radiocarbon dates have been published:[21]

| Lab-Number | Context | cal BCE |

|---|---|---|

| Ua-19561 | enclosure C | 7560–7370 |

| Ua-19562 | enclosure B | 8280–7970 |

| Hd-20025 | Layer III | 9110–8620 |

| Hd-20036 | Layer III | 9130–8800 |

The Hd samples are from charcoal in the fill of the lowest levels of the site and date the end of the active phase of the occupation of Level III – the actual structures will be older. The Ua samples come from pedogenic carbonate coatings on pillars and only indicate the time after the site was abandoned – the terminus ante quem.[22]

Architecture

Göbekli Tepe is on a flat and barren plateau, with buildings fanning in all directions. In the north, the plateau is connected to a neighbouring mountain range by a narrow promontory. In all other directions, the ridge descends steeply into slopes and steep cliffs.[23] On top of the ridge there is considerable evidence of human impact, in addition to the construction of the tell. Excavations have taken place at the southern slope of the tell, south and west of a mulberry that marks an Islamic pilgrimage,[5] but archaeological finds come from the entire plateau. The team has also found many remains of tools.

Göbekli Tepe follows a geometric pattern. The pattern is an equilateral triangle that connects enclosures A, B, and D. This means that the people who built Göbekli Tepe had at least some rudimentary knowledge of geometry.[24] The authors of the paper discuss the implications of their findings. The authors suggest that enclosures A, B, and D are all one complex, and within this complex there is a "hierarchy" with enclosure D at the top. The authors also say that, compared to previous estimations, the amount of manpower required to build Göbekli Tepe should be multiplied by three. Third, the idea that each enclosure was built and functioned individually seems less likely—at least in planning and their early stages—given their findings. But they maintain that their suggestions that enclosures A, B, and D are a single complex makes it unlikely that each enclosure was built separately.[25]

Plateau

The plateau has been transformed by erosion and by quarrying, which took place not only in the Neolithic, but also in classical times. There are four 10-metre-long (33 ft) and 20-centimetre-wide (7.9 in) channels on the southern part of the plateau, interpreted as the remains of an ancient quarry from which rectangular blocks were taken. These possibly are related to a square building in the neighbourhood, of which only the foundation is preserved. Presumably this is the remains of a Roman watchtower that was part of the Limes Arabicus, though this is conjecture.[26]

Most structures on the plateau seem to be the result of Neolithic quarrying, with the quarries being used as sources for the huge, monolithic architectural elements. Their profiles were pecked into the rock, with the detached blocks then levered out of the rock bank.[26] Several quarries where round workpieces had been produced were identified. Their status as quarries was confirmed by the find of a 3-by-3 metre piece at the southeastern slope of the plateau. Unequivocally Neolithic are three T-shaped pillars that had not yet been levered out of the bedrock. The largest of them lies on the northern plateau. It has a length of 7 m (23 ft) and its head has a width of 3 m (10 ft). Its weight may be around 50 tons. The two other unfinished pillars lie on the southern Plateau.

Tell

At the western edge of the hill, a lionlike figure was found. In this area, flint and limestone fragments occur more frequently. It was therefore suggested that this could have been some kind of sculpture workshop.[27] It is unclear, on the other hand, how to classify three phallic depictions from the surface of the southern plateau. They are near the quarries of classical times, making their dating difficult.[28]

Apart from the tell, there is an incised platform with two sockets that could have held pillars, and a surrounding flat bench. This platform corresponds to the complexes from Layer III at the tell. Continuing the naming pattern, it is called "complex E". Owing to its similarity to the cult-buildings at Nevalı Çori it has also been called "Temple of the Rock". Its floor has been carefully hewn out of the bedrock and smoothed, reminiscent of the terrazzo floors of the younger complexes at Göbekli Tepe. Immediately northwest of this area are two cistern-like pits that are believed to be part of complex E. One of these pits has a table-high pin as well as a staircase with five steps.[29]

At the western escarpment, a small cave has been discovered in which a small relief depicting a bovid was found. It is the only relief found in this cave.[28]

Layer III

At this early stage of the site's history, circular compounds or temene first appear. They range from 10 to 30 metres in diameter. Their most notable feature is the presence of T-shaped limestone pillars evenly set within thick interior walls composed of unworked stone. Four such circular structures have been unearthed so far. Geophysical surveys indicate that there are 16 more, enclosing up to eight pillars each, amounting to nearly 200 pillars in all. The slabs were transported from bedrock pits located approximately 100 metres (330 ft) from the hilltop, with workers using flint points to cut through the limestone bedrock.[31]

Two taller pillars stand facing one another at the centre of each circle. Whether the circles were provided with a roof is uncertain. Stone benches designed for sitting are found in the interior.[32] Many of the pillars are decorated with abstract, enigmatic pictograms and carved animal reliefs. The pictograms may represent commonly understood sacred symbols, as known from Neolithic cave paintings elsewhere. The reliefs depict mammals such as lions, bulls, boars, foxes, gazelles, and donkeys; snakes and other reptiles; arthropods such as insects and arachnids; and birds, particularly vultures. At the time the edifice was constructed, the surrounding country was likely to have been forested and capable of sustaining this variety of wildlife, before millennia of human settlement and cultivation led to the near–Dust Bowl conditions prevalent today.[6] Vultures also feature prominently in the iconography of Çatalhöyük and Jericho.

Few humanoid figures have appeared in the art at Göbekli Tepe. Some of the T-shaped pillars have human arms carved on their lower half, however, suggesting to site excavator Schmidt that they are intended to represent the bodies of stylized humans (or perhaps deities). Loincloths appear on the lower half of a few pillars. The horizontal stone slab on top is thought by Schmidt to symbolize shoulders, which suggests that the figures were left headless.[33] Whether they were intended to serve as surrogate worshippers, symbolize venerated ancestors, or represent supernatural, anthropomorphic beings is not known.

Some of the floors in this, the oldest, layer are made of terrazzo (burnt lime); others are bedrock from which pedestals to hold the large pair of central pillars were carved in high relief.[34] Radiocarbon dating places the construction of these early circles in the range of 9600 to 8800 BCE. Carbon dating suggests that (for reasons unknown) the enclosures were backfilled during the Stone Age.

Layer II

Creation of the circular enclosures in layer III later gave way to the construction of small rectangular rooms in layer II. Rectangular buildings make a more efficient use of space compared with circular structures. They often are associated with the emergence of the Neolithic,[35] but the T-shaped pillars, the main feature of the older enclosures, also are present here, indicating that the buildings of Layer II continued to serve the same function in the culture, presumably as sanctuaries.[36] Layer II is assigned to Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB). The several adjoining rectangular, doorless and windowless rooms have floors of polished lime reminiscent of Roman terrazzo floors. Carbon dating has yielded dates between 8800 and 8000 BCE.[37] Several T-pillars up to 1.5 meters tall occupy the center of the rooms. A pair decorated with fierce-looking lions is the rationale for the name "lion pillar building" by which their enclosure is known.[38]

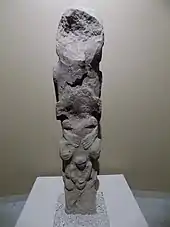

A stone pillar resembling totem pole designs was discovered at Göbekli Tepe, Layer II in 2010. It is 1.92 metres high, and is superficially reminiscent of the totem poles in North America. The pole features three figures, the uppermost depicting a predator, probably a bear, and below it a human-like shape. Because the statue is damaged, the interpretation is not entirely clear. Fragments of a similar pole also were discovered about 20 years ago in another site in Turkey at Nevalı Çori. Also, an older layer at Gobekli features some related sculptures portraying animals on human heads.[39]

Layer I

Layer I is the uppermost part of the hill. It is the shallowest, but accounts for the longest stretch of time. It consists of loose sediments caused by erosion and the virtually-uninterrupted use of the hill for agricultural purposes since it ceased to operate as a ceremonial center.

The site was deliberately backfilled sometime after 8000 BCE: the buildings were buried under debris, mostly flint gravel, stone tools, and animal bones.[40] In addition to Byblos points (weapon heads, such as arrowheads etc.) and numerous Nemrik points, Helwan-points, and Aswad-points dominate the backfill's lithic inventory.

Interpretation

Klaus Schmidt's view was that Göbekli Tepe is a stone-age mountain sanctuary. Radiocarbon dating as well as comparative stylistical analysis indicate that it is the oldest known temple yet discovered anywhere.[6][41] Schmidt believed that what he called this "cathedral on a hill" was a pilgrimage destination attracting worshippers up to 150 km (90 mi) distant. Butchered bones found in large numbers from local game such as deer, gazelle, pigs, and geese have been identified as refuse from food hunted and cooked or otherwise prepared for the congregants.[42] Zooarchaeological analysis shows that gazelle were only seasonally present in the region, suggesting that events such as rituals and feasts were likely timed to occur during periods when game availability was at its peak.[43]

Schmidt considered Göbekli Tepe a central location for a cult of the dead and that the carved animals are there to protect the dead. Though no tombs or graves have yet been found, Schmidt believed that graves remain to be discovered in niches located behind the walls of the sacred circles.[6] In 2017, discovery of human crania with incisions was reported, interpreted as providing evidence for a new form of Neolithic skull cult.[44]

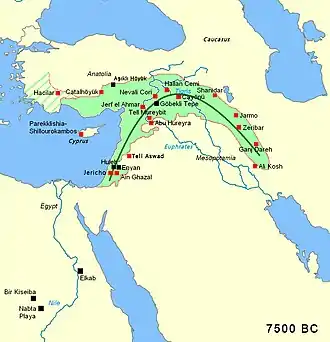

Schmidt also interpreted the site in connection with the initial stages of the Neolithic.[6] It is one of several sites in the vicinity of Karaca Dağ, an area that geneticists suspect may have been the original source of at least some of our cultivated grains (see Einkorn). Recent DNA analysis of modern domesticated wheat compared with wild wheat has shown that its DNA is closest in sequence to wild wheat found on Karaca Dağ 30 km (20 mi) away from the site, suggesting that this is where modern wheat was first domesticated.[45]

With its mountains catching the rain and a calcareous, porous bedrock creating many springs, creeks, and rivers,[46] the upper reaches of the Euphrates and Tigris was a refuge during the dry and cold Younger Dryas climatic event (10,800–9,500 BCE).

Schmidt also engaged in speculation regarding the belief systems of the groups that created Göbekli Tepe, based on comparisons with other shrines and settlements. He presumed shamanic practices and suggested that the T-shaped pillars represent human forms, perhaps ancestors, whereas he saw a fully articulated belief in deities as not developing until later, in Mesopotamia, that was associated with extensive temples and palaces. This corresponds well with an ancient Sumerian belief that agriculture, animal husbandry, and weaving were brought to humans from the sacred mountain Ekur, which was inhabited by Annuna deities, very ancient deities without individual names. Schmidt identified this story as a primeval oriental myth that preserves a partial memory of the emerging Neolithic.[47] It is apparent that the animal and other images give no indication of organized violence, i.e. there are no depictions of hunting raids or wounded animals, and the pillar carvings generally ignore game on which the society depended, such as deer, in favour of formidable creatures such as lions, snakes, spiders, and scorpions.[6][48][49] Expanding on Schmidt's interpretation that round enclosures could represent sanctuaries, Gheorghiu's semiotic interpretation reads the Göbekli Tepe iconography as a cosmogonic map that would have related the local community to the surrounding landscape and the cosmos.[50]

Importance

Göbekli Tepe is regarded by some as an archaeological discovery of great importance since it could profoundly change the understanding of a crucial stage in the development of human society. Ian Hodder of Stanford University said, "Göbekli Tepe changes everything."[2][51] If indeed the site was built by hunter-gatherers, as some researchers believe, then it would mean that the ability to erect monumental complexes was within the capacities of these sorts of groups, which would overturn previous assumptions. Some researchers believe that the construction of Göbekli Tepe may have contributed to the later development of urban civilization, or, as excavator Klaus Schmidt put it, "First came the temple, then the city."[52]

In addition to its large dimensions, the side-by-side existence of multiple pillar shrines makes the location unique. There are no comparable monumental complexes from its time. Since its discovery, however, surface surveys have shown that several hills in the greater area also have 'T'-shaped stone pillars (e.g. Hamzan Tepe,[53] Karahan Tepe,[54] Harbetsuvan Tepesi,[55] Sefer Tepe,[56] and Taslı Tepe[46]) but little excavation has been conducted.

Most of these constructions seem to be smaller than Göbekli Tepe, and their placement evenly between contemporaneous settlements indicates that they were local social-ritual gathering places,[56][46] with Göbekli Tepe perhaps as a regional centre.[57] So far none of the smaller sites are as old as the lowest Level III of Göbekli Tepe,[46] but are contemporary with the younger Level II (mostly rectangular buildings, though Harbetsuvan is circular). This could indicate that this type of architecture and associated activities originated at Göbekli Tepe, and then spread to other sites.

A site that is 500 years younger is Nevalı Çori, a Neolithic settlement. It was excavated by the German Archaeological Institute and has been submerged by the Atatürk Dam since 1992. Its 'T'-shaped pillars are considerably smaller, and its rectangular ceremonial structure was located inside a village. The roughly contemporary architecture at Jericho is devoid of artistic merit or large-scale sculpture, and Çatalhöyük, perhaps the most famous Anatolian Neolithic village, was built 2,000 years later.

It remains unknown how a population large enough to construct, augment, and maintain such a substantial complex was mobilized and compensated or fed in the conditions of pre-sedentary society. Scholars have been unable to interpret the pictograms, and do not know what meaning the animal reliefs had for visitors to the site. The variety of fauna depicted – from lions and boars to birds and insects – makes any single explanation problematic. As there is little or no evidence of habitation, and many of the animals pictured are predators, the stones may have been intended to stave off evils through some form of magic representation. Alternatively, they could have served as totems.[58]

The assumption that the site was strictly cultic in purpose and not inhabited has been challenged as well by the suggestion that the structures served as large communal houses, "similar in some ways to the large plank houses of the Northwest Coast of North America with their impressive house posts and totem poles."[59] It is not known why every few decades the existing pillars were buried to be replaced by new stones as part of a smaller, concentric ring inside the older one.[60]

Conservation

.JPG.webp)

Future plans include construction of a museum and converting the environs into an archaeological park, in the hope that this will help preserve the site in the state in which it was discovered.[5]

In 2010, Global Heritage Fund (GHF) announced it will undertake a multi-year conservation program to preserve Göbekli Tepe. Partners include the German Archaeological Institute, German Research Foundation, Şanlıurfa Municipal Government, the Turkish Ministry of Tourism and Culture and, formerly, Klaus Schmidt.[61]

The stated goals of the GHF Göbekli Tepe project are to support the preparation of a site management and conservation plan, construction of a shelter over the exposed archaeological features, training community members in guiding and conservation, and helping Turkish authorities secure UNESCO World Heritage Site designation for GT.[62]

The conservation work caused controversy in 2018, when Çiğdem Köksal Schmidt, an archaeologist and widow of Klaus Schmidt, said the site was being damaged by the use of concrete and "heavy equipment" during the construction of a new walkway. The Ministry of Culture and Tourism responded that no concrete was used and that no damage had occurred.[63][64]

See also

Notes

- "Göbekli Tepe". Forvo Pronunciation Dictionary.

- "History in the Remaking". Newsweek. 18 February 2010.

- Kosen, Hesen (24 July 2019). "Girê Mirozan Rihayê dike navenda geshtyariyê". Kurdistan 24 (in Kurdish). Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Bakırcı, Çağrı Mert (30 November 2019). "Göbeklitepe Neyi Saklıyor? İnsanlık Tarihi İçin Neden Bu Kadar Önemlidir?" (in Turkish).

- Schmidt 2009, p. 188.

- Curry 2008.

- Oliver Dietrich; Jens Notroff (2015). "A sanctuary, or so fair a house? In defense of an archaeology of cult at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Gobekli Tepe". In Laneri, Nicola (ed.). Defining the Sacred: Approaches to the Archaeology of Religion in the Near East. Oxbow Books. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-78297-685-1. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Sagona, Claudia (25 August 2015). The Archaeology of Malta. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1107006690. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Curry 2008.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Göbekli Tepe". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- The Guardian report 23 April 2008

- "Which came first, monumental building projects or farming?". Archaeo News. 14 December 2008.

- Taracha, Piotr (2009). Religions of second millennium Anatolia. Eisenbrauns. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-447-05885-8.

- Schmidt 2010, pp. 242–3, 249.

- Peter Benedict (1980): Survey Work in Southeastern Anatolia. In: Halet Çambel; Robert J. Braidwood (ed.): Prehistoric Research in Southeastern Anatolia I. Edebiyat Fakültesi Basimevi, Istanbul, pp. 151–191.

- Schmidt 2011, p. 917.

- "Turkey's Ancient Sanctuary". The New Yorker. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "World's Oldest Monument to Receive a Multi-Million Dollar Investment". History.com. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Kazanci, Handan (8 March 2020). "Turkey: Conservation, not excavation, focus in Gobeklitepe". Anadolu Agency.

- Dietrich, Oliver. "Establishing a Radiocarbon Sequence for Göbekli Tepe. State of Research and New Data". Neo-Lithics. 1 (13): 35–37. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Dietrich, Oliver. (2011). Radiocarbon dating the first temples of mankind. Comments on 14C-Dates from Göbekli Tepe. Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie. 4. 12–25.

- "The CANEW Project". 13 March 2009. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009.

- Schmidt 2006, p. 102.

- David, Ariel (28 April 2020). "Israeli Archaeologists Find Hidden Pattern at 'World's Oldest Temple' Göbekli Tepe". Haaretz. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Haklay, Gil; Gopher, Avi (May 2020). "Geometry and Architectural Planning at Göbekli Tepe, Turkey". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 30 (2): 343–357. doi:10.1017/S0959774319000660. ISSN 0959-7743.

- Schmidt 2006, p. 105.

- Schmidt 2006, pp. 109–11.

- Schmidt 2006, p. 111.

- Schmidt 2006, p. 109.

- Schmidt 2011, p. 923.

- Schmidt 2000b, pp. 52–3.

- Mithen 2004, p. 65.

- Schmidt 2010, pp. 244, 246.

- Schmidt 2010, p. 251.

- Flannery & Marcus 2012, p. 128.

- Schmidt 2010, pp. 239, 241.

- Schmidt 2009, p. 291.

- Schmidt 2009, p. 198.

- The Göbekli Tepe ‘Totem Pole’. News & Notes from the Göbekli Tepe Research Staff – 2017-03-01

- Schmidt 2010, p. 242.

- Scham 2008, p. 23.

- Peters & Schmidt 2004, p. 207.

- Lang, Caroline; Peters, Joris; et al. (August 2013). "Gazelle behaviour and human presence at early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, south-east Anatolia". World Archaeology. 45 (3): 410–29. doi:10.1080/00438243.2013.820648.

- Gresky, Julia; Haelm, Juliane; Clare, Lee (28 June 2017). "Modified human crania from Göbekli Tepe provide evidence for a new form of Neolithic skull cult". Science Advances. 3 (6). doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700564..

- Heun, Manfred; et al. (1997). "Site of Einkorn Wheat Domestication Identified by DNA Fingerprinting". Science. 278 (5341): 1312–4. doi:10.1126/science.278.5341.1312.

- Gül, Güler; Çelik, Bahattin; Güler, Mustafa (2013). "New Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites and cult centres in the Urfa Region". Documenta Praehistorica. 40: 291–303. doi:10.4312/dp.40.23.

- Schmidt 2006, pp. 216–21.

- Schmidt 2006, pp. 193–4, 218.

- Peters & Schmidt 2004, p. 209.

- Dragos Gheorghiu (2015); A river runs through it. The semiotics of Gobekli Tepe's map (an exercise of archaeological imagination); in Andrea Vianello (ed.), Rivers in Prehistory, Oxford, Archaeopress

- Symmes 2010.

- Schmidt 2000.

- Çelik, Bahattin (2010). "Hamzan Tepe in the light of new finds". Documenta Praehistorica. 37: 257–68. doi:10.4312/dp.37.22.

- Çelik, Bahattin (2011). "Karahan Tepe: A new cultural centre in the Urfa area in Turkey". Documenta Praehistorica. 38: 241–53. doi:10.4312/dp.38.19.

- Çelik, Bahattin (2016). "A small-scale cult centre in southeast Turkey: Harbetsuvan Tepesi". Documenta Praehistorica. 43: 421–8. doi:10.4312/dp.43.21.

- Güler, Mustafa; Çelik, Bahattin; Gül, Güler (2012). "New pre-pottery neolithic settlements from Viranşehir District". Anadolu / Anatolia. 38: 164–80. doi:10.1501/Andl_0000000398.

- Simmons, Alan H. (15 April 2011). The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the human landscape. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0816501274.

- Peters & Schmidt 2004, pp. 209–12.

- Banning 2011.

- Mann 2011, p. 48.

- "Göbekli Tepe – Turkey". Global Heritage Fund. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011.

- "Göbekli Tepe – Turkey - Overview". Global Heritage Fund. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011.

- "Concrete poured on Turkish World Heritage site". Ahval. 21 March 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- "Construction around site of Göbeklitepe stirs debate". Hürriyet Daily News. 21 March 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

References

- Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe (ed.): "Vor 12.000 Jahren in Anatolien. Die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit." Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung im Badischen Landesmuseum vom 20. Januar bis zum 17. Juni 2007. Theiss, Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-8062-2072-8

- Banning, Edward B. (2011). "So Fair a House: Göbekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East". Current Anthropology. 52 (5 - October 2011): 619–60. doi:10.1086/661207.

- Andrew Curry, "Seeking the Roots of Ritual", Science 319 (18 January 2008), pp. 278–280:

- Curry, Andrew (2008). "Göbekli Tepe: The World's First Temple?". Smithsonian (November 2008). ISSN 0037-7333.

- DVD-ROM: MediaCultura (Hrsg.): Vor 12.000 Jahren in Anatolien. Die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2090-2

- Flannery, Kent; Marcus, Joyce (2012). The Creation of Inequality. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674064690.

- David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce, "An Accidental revolution? Early Neolithic religion and economic change", Minerva, 17 #4 (July/August, 2006), 29–31.

- Klaus-Dieter Linsmeier and Klaus Schmidt: "Ein anatolisches Stonehenge". In: Moderne Archäologie. Spektrum-der-Wissenschaft-Verlag, Heidelberg 2003, 10–15, ISBN 3-936278-35-0.

- Mann, Charles C. (2011). "The Birth of Religion: The World's First Temple". National Geographic. Vol. 219 no. 6 - June 2011.

- Mithen, Steven (2004). After the Ice:A global human history, 20,000–5000 BC. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-67401570-3.

- Peters, Joris; Schmidt, Klaus (2004). "Animals in the symbolic world of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey: a preliminary assessment". Anthropozoologica. 39 (1).

- K. Pustovoytov: Weathering rinds at exposed surfaces of limestone at Göbekli Tepe. In: Neo-lithics. Ex Oriente, Berlin 2000, 24–26 (14C-Dates)

- Erika Qasim: "The T-shaped monuments of Gobekli Tepe: Posture of the Arms". In: Chr. Sütterlin et al. (ed.): Art as Behaviour. An Ethological Approach to Visual and Verbal Art, Music and Architecture. Oldenburg 2014, 252–272

- Scham, Sandra (2008). "The World's First Temple". Archaeology. 61 (6 - November/December 2008).

- Schmidt, Klaus (1998). "Frühneolithische Tempel. Ein Forschungsbericht zum präkeramischen Neolithikum Obermesopotamiens". Mitteilungen der deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. Berlin (130): 17–49. ISSN 0342-118X.

- Schmidt, Klaus (2000). "Zuerst kam der Tempel, dann die Stadt." Vorläufiger Bericht zu den Grabungen am Göbekli Tepe und am Gürcütepe 1995–1999". Istanbuler Mitteilungen (50): 5–41.

- Schmidt, Klaus (2000a). "Göbekli Tepe and the rock art of the Near East". TÜBA-AR (3): 1–14.

- Schmidt, Klaus (2000b). "Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey. A preliminary Report on the 1995–1999 Excavations". Palèorient (CNRS ed.). Paris (26.1): 45–54. ISSN 0153-9345.

- Schmidt, Klaus (2006). Sie bauten die ersten Tempel. Das rätselhafte Heiligtum der Steinzeitjäger (in German). München: C.H. Beck. ISBN 3406535003.

- Schmidt, Klaus (2009). "Göbekli Tepe. Eine Beschreibung der wichtigsten Befunde erstellt nach den Arbeiten der Grabungsteams der Jahre 1995–2007". In Schmidt, Klaus (ed.). Erste Tempel – Frühe Siedlungen. 12000 Jahre Kunst und Kultur, Ausgrabungen und Forschungen zwischen Donau und Euphrat (in German). Oldenburg: Florian Isensee. ISBN 978-3899955637.

- Schmidt, Klaus (2010). "Göbekli Tepe – the Stone Age Sanctuaries: New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs" (PDF). Documenta Praehistorica (XXXVII): 239–56.

Schmidt, Klaus (2011). "Göbekli Tepe: A Neolithic Site in Southwestern Anatolia". In Steadman, Sharon R.; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195376142.

- Metin Yeşilyurt, "Die wissenschaftliche Interpretation von Göbeklitepe: Die Theorie und das Forschungsprogramm". (Neolithikum und ältere Metallzeiten. Studien und Materialien, Band 2.) Lit Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-643-12528-6.

- "Göbekli Tepe". Megalithic Portal.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Göbekli Tepe. |

- Official website

- Göbekli Tepe preservation project summary by Global Heritage Fund

- Explore Göbekli Tepe with Google Earth on Global Heritage Network

- "Tepe Telegrams: News & Notes from the Göbekli Tepe Research Staff". (Official blog, providing frequent updates on the progress of excavations, current interpretations of excavation results, and information on publications and events.)

- 3D model

Articles

- Andreit, Mihai (4 September 2013). "World's oldest temple probably built to worship the dog star, Sirius". ZME Science.

- Batuman, Elif (19 December 2011). "The Sanctuary". The New Yorker. Dept of Archeology.

- Birch, Nicholas (23 April 2008). "7,000 years older than Stonehenge: the site that stunned archaeologists". The Guardian.

- Dietrich, Laura; et al. (2019). "Cereal Processing at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, Southeastern Turkey". PLOS ONE. 14 (5): e0215214. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1415214D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215214. PMC 6493732. PMID 31042741.

- Mann, Charles C. (June 2011). "The Birth of Religion". National Geographic.

- Symmes, Patrick (18 February 2010). "Turkey: Archeological Dig Reshaping Human History". Newsweek.

- Buzzwords, Bogeymen, and Banalities of Pseudoarchaeology: Göbekli Tepe

- Dunning, Brian (21 April 2020). "Skeptoid #724: Decoding Gobekli Tepe". Skeptoid.

Photographs

- "The Birth of Religion". National Geographic. June 2011.

Videos

- Gobeklitepe: The World's First Temple, documentary film

- Göbekli Tepe Reconstructed on YouTube Mar 23, 2009. 3d walkthrough

- RIR-Klaus Schmidt-Göbekli Tepe-The Worlds Oldest Temple? on YouTube Jan 8, 2011. Interview with principal excavator

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.