Nautilus (genus)

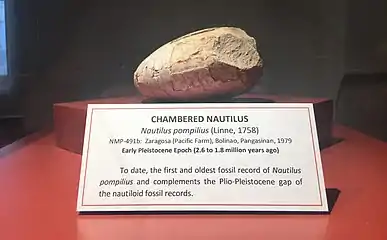

Nautilus is a genus of cephalopods in the family Nautilidae. Species in this genus differ significantly in terms of morphology from those placed in the sister taxon Allonautilus.[1] The oldest fossils of the genus are known from the Late Eocene Hoko River Formation, in Washington State and from Late-Eocene to Early Oligocene sediments in Kazakhstan.[2] The oldest fossils of the modern species Nautilus pompilius are from Early Pleistocene sediments off the coast of Luzon in the Philippines.[2]

| Nautilus | |

|---|---|

| |

| A live Nautilus pompilius in an aquarium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Subclass: | Nautiloidea |

| Order: | Nautilida |

| Family: | Nautilidae |

| Genus: | Nautilus Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| N. pompilius | |

| Species | |

The commonly used term 'nautilus' usually refers to any of the surviving members of Nautilidae, and more specifically to the Nautilus pompilius species. The entire family of Nautilidae, including all species in the genera Nautilus and Allonautilus, was listed on Appendix-II of Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (also known as CITES).[3]

The current consensus is that the genus consists of four valid species, although this remains the subject of debate.[4][5] Nautilus are typically found in shallow waters in tropical seas, mainly within the Indo-Pacific[4]. The genus Nautilus has previously included several species represented in the fossil record, however these have since been reclassified, and the genus now only includes extant species.[6]

Classification

The classification of species within Nautilus has been a source of contention for decades, and the genus has been redefined at several points throughout its history. Nautilus is the type genus of the family Nautilidae, and was originally defined as any coiled shell species with simple sutures, or walls between compartments.[6] Any shells with complex sutures were assigned to the genus Ammonites. This definition of the genus persisted from its inception in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus up to the 1949, when the paleobiologist Arthur K. Miller provided a detailed description of the shell of Nautilus Pompilius, which became the type species of the genus.[6][7] In 1951, he determined that the genus could only describe living species of Nautilus, despite many fossil species having already been assigned to it.[6]

In the years following this conclusion, two newly discovered fossil species were still assigned to the genus however, namely Nautilus Ucrainicus, and Nautilus Praepompilius, recovered from Ukraine, and the Ust-Urt Plateau respectively.[6] These species have since been removed from the genus however.[4]

As of 2010, 11 species have been described, some of which feature several variants, or subspecies. The details of their classification are listed below.[4]

| Described Species | Status |

| N. pompilius | Valid |

| N. ambiguus | Nomen Dubium |

| N. alumnus | Nomen Dubium |

| N. belauensis | Valid |

| N. macromphalus | Valid |

| N. scrobiculatus | Reclassified as Allonautilus |

| N. umbiliculatus | Synonym of N. Scrobiculatus |

| N. perforatus | Synonym of N. scrobiculatus |

| N. texturatus | Synonym of N. scrobiculatus |

| N. stenomphalus | Valid |

| N. repertus | Nomen Dubium: likely a giant form of N. Pompilius[4][8] |

Controversy over species

There has been much debate over the validity of species within the genus, and several identified species have since been reclassified, or determined as taxonomic synonyms or nomen dubium (a doubtful classification). As of 2015, only four Nautilus species have been recognised, specifically N. Pompilius, N. Macromphalus, N. Stenomphalus, and N. Belauensis.[5] Nautilus Scrobiculatus, now Allonautilus Scrobiculatus has been assigned to a new genus,[1] and several species listed above have been identified as synonyms of this species, namely N. Umbiculatus, N. Perforatus, and N. Texturatus[4]. Much of the confusion regarding the classification of species is due to the rarity of live species. The majority of described species have been determined on the drift shells of individuals alone, leading to inaccuracies when defining species divisions.[9] In fact, it was not until 1996, that soft tissues of any Nautilus species had been dissected[5].

Genetic Studies

Several genetic studies have also been conducted on select species of Nautilus, from 1995 onwards, most of which focus on a single gene, called COI. These studies ultimately lead to the decision to remove N.Scrobiculatus from the genus.[5] Furthermore, some biologists claim that N.Stenomphalus and N. Belauensis are members of N. Pompilius based on both genetic and morphological data.[5] One study, sampling Nautiluses in 2012, demonstrated that the features of Nautilus Pompilius and Nautilus Stenomphalus exist along a spectrum, with a range of individuals displaying a combination of characteristics, further invalidating them as separate species.[5]

Additionally, mitochondrial DNA studies, utilising two gene regions, also have led to the notion that many of the morphological differences between different Nautilus populations are simply localised variations within the single Nautilus species.[10] This same 2011 study however, suggested that N. Macronphalus was a species synonymous with A.Scrobiculatus, leading to further debate over classification. These findings were also reinforced by the initial DNA studies conducted on the genus, which only revealed two phylogenetic species.[11]

More recently, a 2017 study determined that there were likely five Nautilus species, however these did not exactly correlate to the described species of the genus.[8] Whilst the status of N. Macromphalus, N. Stenomphalus, and N. Pompilius were validated by the genetic study, two undescribed, but genetically distinct, species were discovered in the South Pacific.[8] One of these cryptic species was recorded from Vanuatu, whilst the other from Fiji and American Samoa. Whilst this study recorded five species, its results suggested that N. Belauensis and N. Repertus were synonyms with N. Pompilius.[8]

Evolution

In addition to defining species, genetic studies have also provided evidence for the evolution of the genus over time. Mitochondrial DNA studies have indicated that the genus is currently undergoing evolutionary radiation in the Indo-Pacific.[10] The divergence between the genus Nautilus, and its sister taxon Allonautilus likely occurred around New Guinea, and the Great Barrier Reef,[10] during the Mesozoic.[1] From there, populations of Nautilus split diverged further, involving migrations east to Vanuatu, Fiji, and American Samoa, as well as west, to the Philippines, Palau, Indonesia, and western Australia.[10]

Sensory Organs

Nautilus have unique sensory organs, which differ from related genera in several ways. Unlike other cephalopods, the eyes of Nautilus species lack ocular muscles, and instead move via a stalk, which contains both muscle and connective tissue. Additionally, Nautilus eyes lack any lens or cornea, and only have an aperture to allow for light.

Below their eyes, Nautilus also feature rhinophores, which are small sacs with cilia.[12] It has been suggested that this organ contains chemoreceptors, in order to detect food, or sample the surrounding water.[12] Additionally, the tentacles of the Nautilus also perform several sensory functions. Their ocular and preocular tentacles feature cilia, and operate as mechanoreceptors, while their digital tentacles have been hypothesised to feature a range of receptor cells.[12]

Habitat and Distribution

Species within the genus Nautilus are localised to the Indo-Pacific, specifically the tropical seas within this area,[6] however the full extent of their geographic distribution has yet to be recorded.[4] The movements of Nautilus species are greatly restricted by water depth. Nautilus are unable to easily move across areas deeper than 800m, and most of their activity occurs at a depth of 100-300m deep.[4] Nautilus can occasionally be found closer to the surface than 100m, however the minimum depth they can reach is determined by factors such as water temperature and season.[4] All Nautilus species are likely endangered, based on information from Nautilus Pompilius overfishing in the Philippines, which resulted in an 80% decline in the population from 1980 to 2010.[13]

_(offshore_from_Broome%252C_Western_Australia)_(24052390712).jpg.webp)

Many shells recovered from areas of the world have not yet been identified down to the level of species, however are still identifiable as members of the genus Nautilus. Shells have been found across a wide range of coastal areas, including Korea, Australia, Seychelles, Maritius, the Philippines, Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, India, Sri Lanka, Kenya, and South Africa.[4] This does not necessarily imply live populations of Nautilus at these sites however, as Nautilus drift shells are able to make their way across oceans via currents. Following the death of an individual, Nautilus shells float can to the surface, where they can remain for a considerable time period,[4] however the buoyancy of shells after death was found to be dependent on a number of factors, such as the rate of decay.[14] An experiment with a Nautilus shell in an aquarium resulted in the shell floating for over two years, and one recovered shell was revealed to have been afloat for a period of 11 years.[4] Furthermore, shells have been demonstrated to drift considerable distances in this time, contributing to their extensive distribution across coastal areas. Several ocean currents have been identified to contribute to this process. The Kuroshio current carries shells from the Philippines to areas such as Japan, and the Equatorial current is responsible for many of the shells recovered from the Marshall Islands.[4]

Behaviour

Nautilus have been observed to spend days in deeper areas around coral reefs, to avoid predation from turtles and carnivorous fish, and ascend to shallow areas of the reef during nights.[15][9] Here, they engage in scavenging activity, seeking out animal remains, and the moults of crustaceans. Nautilus species usually travel, and feed alone. Nautilus return to deeper areas following daybreak, and also lay eggs in these locations, which take approximately one year to hatch.[9] This behaviour may have ensured their survival during the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction, when shallow areas of ocean became inhospitable.[9] Nautilus have been noted to exhibit an extensive range of depth, close to 500m, however they were demonstrated to be at risk of implosion, when exceeding their depth and pressure limits. Depending on the species, the shells of live Nautilus will collapse at depths of 750 metres or deeper.[15][4]

The feeding behaviour of the genus has been identified from observation of captive individuals, as well as the stomach contents of wild specimens. Nautilus are opportunistic scavengers, and feed on a variety of crustaceans, including their moults, and fish, however they have been observed to feed on chicken and bat bait.[4] Initially, Nautilus were thought to actively hunt certain prey, however this activity has only been recorded in traps, where prey species are confined in close proximity to Nautilus. Nautilus locate these food sources by using their tentacles, which have chemosensory functions, as well as by sight. Nautilus participate in routine vertical migration,[15] in which they ascend to shallow areas of reefs, between 100 and 150 metres deep, during the night to feed, and later descend to depths of 250–350 metres during the day, however these depths may vary depending on local geographic characteristics.[4] Nautilus are able to ascend at speeds of approximately 2 metres per minute, and descend at speeds of 3 metres per minute.[4]

Predation

Several species have been observed to prey on Nautilus. Octopi were listed as predators of the genus, following an incident where an octopus was shown to have partially consumed a Nautilus in a trap. Additionally many drift shells exhibit small holes which match the patterns produced by octopus boring into shell to feed.[4] Teleosts, such as triggerfish, have also been observed to feed on Nautilus, by violently charging at individuals to break their shells. In response to attacks from predators, Nautilus withdraw into their shells.[4]

Nautilus in Aquaria

It is possible to keep Nautilus in aquaria, however specific care is necessary in order to ensure their survival in captivity. The survival rate of Nautilus in captivity is relatively poor, primarily due to the stress that individuals are subjected to during transportation. As many as 50-80% of Nautilus die during transportation, and this percentage can be higher, if individuals are exposed to high temperatures.[4] In captivity, Nautilus are generally fed a diet of whole shrimp, fish, crab, and lobster moults.[4][16] Several aquaria around the world host specimens of the genus, however there have not yet been any successful attempts of breeding in captivity, despite viable eggs being produced at several locations.[4] Two Nautilus eggs were hatched at Waikiki Aquarium, however these individuals both died months later.[16]

In addition to observing wild specimens, our knowledge of Nautilus temperature thresholds is also supplemented by the study of captive individuals in aquaria. Captive Nautilus specimens have demonstrated that prolonged exposure to temperatures over 25 degrees Celsius will eventually result in death after several days. However, individuals have been documented to experience temperatures higher than this, and survive, as long as they are not exposed to these temperatures for longer than 10 hours. Optimal temperatures for the genus tend to range from 9-21 degrees Celsius.[4]

Reproduction

The majority of our knowledge regarding Nautilus reproduction comes from captive species in Aquaria. From these specimens, it appears that Nautilus do not have an elaborate courtship process. Males have been observed to attempt to mate with any object the same size and shape as another Nautilus. If a male is successful in finding a female however, the mating process follows, and afterwards, the male may continue to hold onto the female for a period ranging from minutes to hours.[4]

Nautilus eggs are laid in capsules, usually 3–4 cm long,[16] which gradually harden when exposed to sea water.[4] It is not yet known how exactly the juveniles break out of these capsules, yet it has been hypothesised that they are able to chew their way out, using their beak. The genus exhibits a skewed sex ratio, biased towards male individuals. This phenomenon has been observed at several locations around the globe, with population samples consisting of up to 95% males. The reason for this is currently unknown.[4]

References

- Ward, P.D. & W.B. Saunders 1997. Allonautilus: a new genus of living nautiloid cephalopod and its bearing on phylogeny of the Nautilida. Journal of Paleontology 71(6): 1054–1064.

- Wani, R.; et al. (2008). "First discovery of fossil Nautilus pompilius (Nautilidae, Cephalopoda) from Pangasinan, northwestern Philippines". Paleontological Research. 12 (1): 89–95. doi:10.2517/1342-8144(2008)12[89:FDOFNP]2.0.CO;2.

- "Checklist of CITES species".

- Saunders, W. Bruce. Landman, Neil H. (2010). Nautilus : the biology and paleobiology of a living fossil. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-3298-0. OCLC 613896438.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ward, Peter; Dooley, Frederick; Barord, Gregory Jeff (2016-02-29). "Nautilus: biology, systematics, and paleobiology as viewed from 2015". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 135 (1): 169–185. doi:10.1007/s13358-016-0112-7. ISSN 1664-2376. S2CID 87025055.

- Teichert, Curt; Matsumoto, Tatsuro (1987), "The Ancestry of the Genus Nautilus", Topics in Geobiology, Springer US, pp. 25–32, doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-5040-6_2, ISBN 978-1-4899-5042-0

- Miller, A. K. (September 1949). "The Last Surge of the Nautiloid Cephalopods". Evolution. 3 (3): 231–238. doi:10.2307/2405560. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 2405560. PMID 18138384.

- Combosch, David J.; Lemer, Sarah; Ward, Peter D.; Landman, Neil H.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2017-10-07). "Genomic signatures of evolution in Nautilus —An endangered living fossil". Molecular Ecology. 26 (21): 5923–5938. doi:10.1111/mec.14344. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 28872211.

- "Coils of Time". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

- Bonacum, James; Landman, Neil H.; Mapes, Royal H.; White, Matthew M.; White, Alicia-Jeannette; Irlam, Justin (March 2011). "Evolutionary Radiation of Present-DayNautilusandAllonautilus". American Malacological Bulletin. 29 (1–2): 77–93. doi:10.4003/006.029.0221. ISSN 0740-2783. S2CID 86014620.

- Wray, Charles G.; Landman, Neil H.; Saunders, W. Bruce; Bonacum, James (1995). "Genetic divergence and geographic diversification in Nautilus". Paleobiology. 21 (2): 220–228. doi:10.1017/s009483730001321x. ISSN 0094-8373.

- Barber, V. C.; Wright, D. E. (1969). "The fine structure of the sense organs of the cephalopod mollusc Nautilus". Zeitschrift fr Zellforschung und Mikroskopische Anatomie. 102 (3): 293–312. doi:10.1007/bf00335442. ISSN 0302-766X. PMID 4903946. S2CID 19565604.

- Dunstan, A.; Alanis, O.; Marshall, J. (November 2010). "Nautilus pompilius fishing and population decline in the Philippines: A comparison with an unexploited Australian Nautilus population". Fisheries Research. 106 (2): 239–247. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2010.06.015. ISSN 0165-7836.

- Chamberlain, John A.; Ward, Peter D.; Weaver, J. Scott (1981). "Post-mortem ascent of Nautilus shells: implications for cephalopod paleobiogeography". Paleobiology. 7 (4): 494–509. doi:10.1017/s0094837300025549. ISSN 0094-8373.

- Dunstan, Andrew J.; Ward, Peter D.; Marshall, N. Justin (2011-02-22). "Vertical Distribution and Migration Patterns of Nautilus pompilius". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e16311. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016311. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3043052. PMID 21364981.

- Landman, Neil H.; Cochran, J. Kirk; Rye, Danny M.; Tanabe, Kazushige; Arnold, John M. (1994). "Early life history of Nautilus: evidence from isotopic analyses of aquarium-reared specimens". Paleobiology. 20 (1): 40–51. doi:10.1017/s009483730001112x. ISSN 0094-8373.