Nereid (moon)

Nereid /ˈnɪəriːɪd/, or Neptune II, is the third-largest moon of Neptune. Of all known moons in the Solar System, it has the most eccentric orbit.[8] It was the second moon of Neptune to be discovered, by Gerard Kuiper in 1949.

Nereid imaged by Voyager 2 in 1989 | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Gerard P. Kuiper |

| Discovery date | 1 May 1949 |

| Designations | |

Designation | Neptune II |

| Pronunciation | /ˈnɪəriːɪd/[2] |

Named after | pl. Νηρηΐδες, Νηρεΐδες Nērēïdes, Nēreïdes |

| Adjectives | Nereidian or Nereidean, both /nɛriːˈɪdiən/[3] |

| Orbital characteristics[4] | |

| Epoch 27 April 2019 (JD 2458600.5) | |

| Observation arc | 68.21 yr (24,897 d) |

| 5,513,940 km (0.0368584 AU) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.7417482 |

| 0.987 yr (360.11 d) | |

| 69.95747° | |

| 0° 59m 58.86s / day | |

| Inclination | 5.04909° (to the ecliptic) 7.090° (to local Laplace plane)[5] |

| 319.42404° | |

| 296.50396° | |

| Satellite of | Neptune |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean diameter | 357±13 km[6] 340±50 km[7] |

| 11.594±0.017 h[6] | |

| Albedo | 0.24[6] 0.155[7] |

| Temperature | ≈50 K (mean estimate) |

| 19.2[7] | |

| 4.4[4] | |

Discovery and naming

Nereid was discovered on 1 May 1949 by Gerard P. Kuiper on photographic plates taken with the 82-inch telescope at the McDonald Observatory. He proposed the name in the report of his discovery. It is named after the Nereids, sea-nymphs of Greek mythology and attendants of the god Neptune.[1] It was the second and last moon of Neptune to be discovered before the arrival of Voyager 2 (not counting a single observation of an occultation by Larissa in 1981).[9]

Physical characteristics

Nereid is third-largest of Neptune's satellites, and has a mean radius of about 180 kilometres (110 mi).[6] It is rather large for an irregular satellite.[10] The shape of Nereid is unknown.[11]

Since 1987 some photometric observations of Nereid have detected large (by ~1 of magnitude) variations of its brightness, which can happen over years and months, but sometimes even over a few days. They persist even after a correction for distance and phase effects. On the other hand, not all astronomers who have observed Nereid have noticed such variations. This means that they may be quite chaotic. To date there is no credible explanation of the variations, but, if they exist, they are likely related to the rotation of Nereid. Nereid's rotation could be either in the state of forced precession or even chaotic rotation (like Hyperion) due to its highly elliptical orbit.

In 2016, extended observations with the Kepler space telescope showed only low-amplitude variations (0.033 magnitudes). Thermal modeling based on infrared observations from the Spitzer and Herschel space telescopes suggest that Nereid is only moderately elongated with an aspect ratio of 1.3:1, which disfavors forced precession of the rotation.[6] The thermal model also indicates that the surface roughness of Nereid is very high, likely similar to the Saturnian moon Hyperion.[6]

Spectrally, Nereid appears neutral in colour[12] and water ice has been detected on its surface.[13] Its spectrum appears to be intermediate between Uranus's moons Titania and Umbriel, which suggests that Nereid's surface is composed of a mixture of water ice and some spectrally neutral material.[13] The spectrum is markedly different from minor planets of the outer solar system, centaurs Pholus, Chiron and Chariklo, suggesting that Nereid formed around Neptune rather than being a captured body.[13]

Halimede, which displays a similar gray neutral colour, may be a fragment of Nereid that was broken off during a collision.[12]

Orbit and rotation

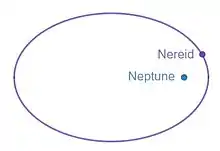

Nereid orbits Neptune in the prograde direction at an average distance of 5,513,400 km (3,425,900 mi), but its high eccentricity of 0.7507 takes it as close as 1,372,000 km (853,000 mi) and as far as 9,655,000 km (5,999,000 mi).[5][14]

The unusual orbit suggests that it may be either a captured asteroid or Kuiper belt object, or that it was an inner moon in the past and was perturbed during the capture of Neptune's largest moon Triton.[13] If the latter is true, it may be the only survivor of Neptune's original (pre-Triton capture) set of regular satellites.[15]

In 1991, a rotation period of Nereid of about 13.6 hours was determined by an analysis of its light curve.[16] In 2003, another rotation period of about 11.52 ± 0.14 hours was measured.[10] However, this determination was later disputed, and other researchers for a time failed to detect any periodic modulation in Nereid's light curve from ground-based observations.[11] In 2016, a clear rotation period of 11.594 ± 0.017 hours was determined based on observations with the Kepler space telescope.[6]

Exploration

The only spacecraft to visit Nereid was Voyager 2, which passed it at a distance of 4,700,000 km (2,900,000 mi)[17] between 20 April and 19 August 1989.[18] Voyager 2 obtained 83 images with observation accuracies of 70 km (43 mi) to 800 km (500 mi).[18] Prior to Voyager 2's arrival, observations of Nereid had been limited to ground-based observations that could only establish its intrinsic brightness and orbital elements.[19] Although the images obtained by Voyager 2 do not have a high enough resolution to allow surface features to be distinguished, Voyager 2 was able to measure the size of Nereid and found that it was grey in colour and had a higher albedo than Neptune's other small satellites.[9]

See also

References

- Kuiper, G. P. (August 1949). "The Second Satellite of Neptune". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 61 (361): 175–176. Bibcode:1949PASP...61..175K. doi:10.1086/126166.

- "Nereid". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "nereidian, nereidean". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "M.P.C. 115892" (PDF). Minor Planet Circular. Minor Planet Center. 27 August 2019.

- Jacobson, R. A. — AJ (2009-04-03). "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters". JPL satellite ephemeris. JPL (Solar System Dynamics). Archived from the original on October 14, 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- Kiss, C.; Pál, A.; Farkas-Takács, A. I.; Szabó, G. M.; Szabó, R.; Kiss, L. L.; et al. (April 2016). "Nereid from space: Rotation, size and shape analysis from K2, Herschel and Spitzer observations" (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 457 (3): 2908–2917. arXiv:1601.02395. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.457.2908K. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw081.

- "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). Archived from the original on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters". NASA. 2013-08-23. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L. A.; Banfield, D.; Barnet, C.; Basilevsky, A. T.; Beebe, R. F.; Bollinger, K.; Boyce, J. M.; Brahic, A. (1989). "Voyager 2 at Neptune: Imaging Science Results". Science. 246 (4936): 1422–1449. Bibcode:1989Sci...246.1422S. doi:10.1126/science.246.4936.1422. PMID 17755997.

- Grav, T.; M. Holman; J. J. Kavelaars (2003). "The Short Rotation Period of Nereid". The Astrophysical Journal. 591 (1): 71–74. arXiv:astro-ph/0306001. Bibcode:2003ApJ...591L..71G. doi:10.1086/377067.

- Schaefer, Bradley E.; Tourtellotte, Suzanne W.; Rabinowitz, David L.; Schaefer, Martha W. (2008). "Nereid: Light curve for 1999–2006 and a scenario for its variations". Icarus. 196 (1): 225–240. arXiv:0804.2835. Bibcode:2008Icar..196..225S. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.02.025.

- Grav, Tommy; Holman, Matthew J.; Fraser, Wesley C. (2004-09-20). "Photometry of Irregular Satellites of Uranus and Neptune". The Astrophysical Journal. 613 (1): L77–L80. arXiv:astro-ph/0405605. Bibcode:2004ApJ...613L..77G. doi:10.1086/424997.

- Brown, Michael E.; Koresko, Christopher D.; Blake, Geoffrey A. (December 1998). "Detection of Water Ice on Nereid". The Astrophysical Journal. 508 (2): L175–L176. Bibcode:1998ApJ...508L.175B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.24.1200. doi:10.1086/311741. PMID 11542819.

- Jacobson, R. A. (3 April 2009). "The Orbits of the Neptunian Satellites and the Orientation of the Pole of Neptune". The Astronomical Journal. 137 (5): 4322–4329. Bibcode:2009AJ....137.4322J. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/5/4322.

- Brozović, M.; Showalter, M. R.; Jacobson, R. A.; French, R. S.; Lissauer, J. J.; de Pater, I. (March 2020). "Orbits and resonances of the regular moons of Neptune". Icarus. 338: 113462. arXiv:1910.13612. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.113462.

- Williams, I.P.; Jones, D.H.P.; Taylor, D.B. (1991). "The rotation period of Nereid". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 250: 1P–2P. Bibcode:1991MNRAS.250P...1W. doi:10.1093/mnras/250.1.1p.

- Jones, Brian (1991). Exploring the Planets. Italy: W.H. Smith. pp. 59. ISBN 978-0-8317-6975-8.

- Jacobson, R.A. (1991). "Triton and Nereid astrographic observations from Voyager 2". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 90 (3): 541–563. Bibcode:1991A&AS...90..541J.

- "PIA00054: Nereid". NASA. 1996-01-29. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

_flatten_crop.jpg.webp)