Albedo

Albedo (/ælˈbiːdoʊ/) (Latin: albedo, meaning 'whiteness') is the measure of the diffuse reflection of solar radiation out of the total solar radiation and measured on a scale from 0, corresponding to a black body that absorbs all incident radiation, to 1, corresponding to a body that reflects all incident radiation.

Surface albedo is defined as the ratio of radiosity to the irradiance (flux per unit area) received by a surface.[1] The proportion reflected is not only determined by properties of the surface itself, but also by the spectral and angular distribution of solar radiation reaching the Earth's surface.[2] These factors vary with atmospheric composition, geographic location and time (see position of the Sun). While bi-hemispherical reflectance is calculated for a single angle of incidence (i.e., for a given position of the Sun), albedo is the directional integration of reflectance over all solar angles in a given period. The temporal resolution may range from seconds (as obtained from flux measurements) to daily, monthly, or annual averages.

Unless given for a specific wavelength (spectral albedo), albedo refers to the entire spectrum of solar radiation.[3] Due to measurement constraints, it is often given for the spectrum in which most solar energy reaches the surface (between 0.3 and 3 μm). This spectrum includes visible light (0.4–0.7 μm), which explains why surfaces with a low albedo appear dark (e.g., trees absorb most radiation), whereas surfaces with a high albedo appear bright (e.g., snow reflects most radiation).

Albedo is an important concept in climatology, astronomy, and environmental management (e.g., as part of the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program for sustainable rating of buildings). The average albedo of the Earth from the upper atmosphere, its planetary albedo, is 30–35% because of cloud cover, but widely varies locally across the surface because of different geological and environmental features.[4]

The term albedo was introduced into optics by Johann Heinrich Lambert in his 1760 work Photometria.

Terrestrial albedo

| Surface | Typical albedo |

|---|---|

| Fresh asphalt | 0.04[5] |

| Open ocean | 0.06[6] |

| Worn asphalt | 0.12[5] |

| Conifer forest (Summer) | 0.08[7] 0.09 to 0.15[8] |

| Deciduous forest | 0.15 to 0.18[8] |

| Bare soil | 0.17[9] |

| Green grass | 0.25[9] |

| Desert sand | 0.40[10] |

| New concrete | 0.55[9] |

| Ocean ice | 0.50 to 0.70[9] |

| Fresh snow | 0.80[9] |

Any albedo in visible light falls within a range of about 0.9 for fresh snow to about 0.04 for charcoal, one of the darkest substances. Deeply shadowed cavities can achieve an effective albedo approaching the zero of a black body. When seen from a distance, the ocean surface has a low albedo, as do most forests, whereas desert areas have some of the highest albedos among landforms. Most land areas are in an albedo range of 0.1 to 0.4.[11] The average albedo of Earth is about 0.3.[12] This is far higher than for the ocean primarily because of the contribution of clouds.

Earth's surface albedo is regularly estimated via Earth observation satellite sensors such as NASA's MODIS instruments on board the Terra and Aqua satellites, and the CERES instrument on the Suomi NPP and JPSS. As the amount of reflected radiation is only measured for a single direction by satellite, not all directions, a mathematical model is used to translate a sample set of satellite reflectance measurements into estimates of directional-hemispherical reflectance and bi-hemispherical reflectance (e.g.,[13]). These calculations are based on the bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF), which describes how the reflectance of a given surface depends on the view angle of the observer and the solar angle. BDRF can facilitate translations of observations of reflectance into albedo.

Earth's average surface temperature due to its albedo and the greenhouse effect is currently about 15 °C. If Earth were frozen entirely (and hence be more reflective), the average temperature of the planet would drop below −40 °C.[14] If only the continental land masses became covered by glaciers, the mean temperature of the planet would drop to about 0 °C.[15] In contrast, if the entire Earth was covered by water – a so-called ocean planet – the average temperature on the planet would rise to almost 27 °C.[16]

White-sky, black-sky, and blue-sky albedo

For land surfaces, it has been shown that the albedo at a particular solar zenith angle θi can be approximated by the proportionate sum of two terms:

- the directional-hemispherical reflectance at that solar zenith angle, , sometimes referred to as black-sky albedo, and

- the bi-hemispherical reflectance, , sometimes referred to as white-sky albedo.

with being the proportion of direct radiation from a given solar angle, and being the proportion of diffuse illumination, the actual albedo (also called blue-sky albedo) can then be given as:

This formula is important because it allows the albedo to be calculated for any given illumination conditions from a knowledge of the intrinsic properties of the surface.[17]

Astronomical albedo

The albedos of planets, satellites and minor planets such as asteroids can be used to infer much about their properties. The study of albedos, their dependence on wavelength, lighting angle ("phase angle"), and variation in time composes a major part of the astronomical field of photometry. For small and far objects that cannot be resolved by telescopes, much of what we know comes from the study of their albedos. For example, the absolute albedo can indicate the surface ice content of outer Solar System objects, the variation of albedo with phase angle gives information about regolith properties, whereas unusually high radar albedo is indicative of high metal content in asteroids.

Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, has one of the highest known albedos of any body in the Solar System, with an albedo of 0.99. Another notable high-albedo body is Eris, with an albedo of 0.96.[18] Many small objects in the outer Solar System[19] and asteroid belt have low albedos down to about 0.05.[20] A typical comet nucleus has an albedo of 0.04.[21] Such a dark surface is thought to be indicative of a primitive and heavily space weathered surface containing some organic compounds.

The overall albedo of the Moon is measured to be around 0.14,[22] but it is strongly directional and non-Lambertian, displaying also a strong opposition effect.[23] Although such reflectance properties are different from those of any terrestrial terrains, they are typical of the regolith surfaces of airless Solar System bodies.

Two common albedos that are used in astronomy are the (V-band) geometric albedo (measuring brightness when illumination comes from directly behind the observer) and the Bond albedo (measuring total proportion of electromagnetic energy reflected). Their values can differ significantly, which is a common source of confusion.

| Planet | Geometric | Bond |

|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.14 [24] | 0.09 [25] |

| Venus | 0.69 [24] | 0.76 [26] |

| Earth | 0.43 [24] | 0.31 [27] |

| Mars | 0.17 [24] | 0.25 [28] |

| Jupiter | 0.54 [24] | 0.50 [29] |

| Saturn | 0.50 [24] | 0.34 [30] |

| Uranus | 0.49 [24] | 0.30 [31] |

| Neptune | 0.44 [24] | 0.29 [32] |

In detailed studies, the directional reflectance properties of astronomical bodies are often expressed in terms of the five Hapke parameters which semi-empirically describe the variation of albedo with phase angle, including a characterization of the opposition effect of regolith surfaces.

The correlation between astronomical (geometric) albedo, absolute magnitude and diameter is:[33] ,

where is the astronomical albedo, is the diameter in kilometers, and is the absolute magnitude.

Examples of terrestrial albedo effects

Illumination

Albedo is not directly dependent on illumination because changing the amount of incoming light proportionally changes the amount of reflected light, except in circumstances where a change in illumination induces a change in the Earth's surface at that location (e.g. through melting of reflective ice). That said, albedo and illumination both vary by latitude. Albedo is highest near the poles and lowest in the subtropics, with a local maximum in the tropics.[34]

Insolation effects

The intensity of albedo temperature effects depends on the amount of albedo and the level of local insolation (solar irradiance); high albedo areas in the arctic and antarctic regions are cold due to low insolation, whereas areas such as the Sahara Desert, which also have a relatively high albedo, will be hotter due to high insolation. Tropical and sub-tropical rainforest areas have low albedo, and are much hotter than their temperate forest counterparts, which have lower insolation. Because insolation plays such a big role in the heating and cooling effects of albedo, high insolation areas like the tropics will tend to show a more pronounced fluctuation in local temperature when local albedo changes.

Arctic regions notably release more heat back into space than what they absorb, effectively cooling the Earth. This has been a concern since arctic ice and snow has been melting at higher rates due to higher temperatures, creating regions in the arctic that are notably darker (being water or ground which is darker color) and reflects less heat back into space. This feedback loop results in a reduced albedo effect.[35]

Climate and weather

Albedo affects climate by determining how much radiation a planet absorbs.[36] The uneven heating of Earth from albedo variations between land, ice, or ocean surfaces can drive weather.

Albedo–temperature feedback

When an area's albedo changes due to snowfall, a snow–temperature feedback results. A layer of snowfall increases local albedo, reflecting away sunlight, leading to local cooling. In principle, if no outside temperature change affects this area (e.g., a warm air mass), the raised albedo and lower temperature would maintain the current snow and invite further snowfall, deepening the snow–temperature feedback. However, because local weather is dynamic due to the change of seasons, eventually warm air masses and a more direct angle of sunlight (higher insolation) cause melting. When the melted area reveals surfaces with lower albedo, such as grass or soil, the effect is reversed: the darkening surface lowers albedo, increasing local temperatures, which induces more melting and thus reducing the albedo further, resulting in still more heating.

Snow

Snow albedo is highly variable, ranging from as high as 0.9 for freshly fallen snow, to about 0.4 for melting snow, and as low as 0.2 for dirty snow.[37] Over Antarctica snow albedo averages a little more than 0.8. If a marginally snow-covered area warms, snow tends to melt, lowering the albedo, and hence leading to more snowmelt because more radiation is being absorbed by the snowpack (the ice–albedo positive feedback).

Just as fresh snow has a higher albedo than does dirty snow, the albedo of snow-covered sea ice is far higher than that of sea water. Sea water absorbs more solar radiation than would the same surface covered with reflective snow. When sea ice melts, either due to a rise in sea temperature or in response to increased solar radiation from above, the snow-covered surface is reduced, and more surface of sea water is exposed, so the rate of energy absorption increases. The extra absorbed energy heats the sea water, which in turn increases the rate at which sea ice melts. As with the preceding example of snowmelt, the process of melting of sea ice is thus another example of a positive feedback.[38] Both positive feedback loops have long been recognized as important for global warming.

Cryoconite, powdery windblown dust containing soot, sometimes reduces albedo on glaciers and ice sheets.[39]

The dynamical nature of albedo in response to positive feedback, together with the effects of small errors in the measurement of albedo, can lead to large errors in energy estimates. Because of this, in order to reduce the error of energy estimates, it is important to measure the albedo of snow-covered areas through remote sensing techniques rather than applying a single value for albedo over broad regions.

Small-scale effects

Albedo works on a smaller scale, too. In sunlight, dark clothes absorb more heat and light-coloured clothes reflect it better, thus allowing some control over body temperature by exploiting the albedo effect of the colour of external clothing.[40]

Solar photovoltaic effects

Albedo can affect the electrical energy output of solar photovoltaic devices. For example, the effects of a spectrally responsive albedo are illustrated by the differences between the spectrally weighted albedo of solar photovoltaic technology based on hydrogenated amorphous silicon (a-Si:H) and crystalline silicon (c-Si)-based compared to traditional spectral-integrated albedo predictions. Research showed impacts of over 10%.[41] More recently, the analysis was extended to the effects of spectral bias due to the specular reflectivity of 22 commonly occurring surface materials (both human-made and natural) and analyzes the albedo effects on the performance of seven photovoltaic materials covering three common photovoltaic system topologies: industrial (solar farms), commercial flat rooftops and residential pitched-roof applications.[42]

Trees

Because forests generally have a low albedo, (the majority of the ultraviolet and visible spectrum is absorbed through photosynthesis), some scientists have suggested that greater heat absorption by trees could offset some of the carbon benefits of afforestation (or offset the negative climate impacts of deforestation). In the case of evergreen forests with seasonal snow cover albedo reduction may be great enough for deforestation to cause a net cooling effect.[43] Trees also impact climate in extremely complicated ways through evapotranspiration. The water vapor causes cooling on the land surface, causes heating where it condenses, acts a strong greenhouse gas, and can increase albedo when it condenses into clouds.[44] Scientists generally treat evapotranspiration as a net cooling impact, and the net climate impact of albedo and evapotranspiration changes from deforestation depends greatly on local climate.[45]

In seasonally snow-covered zones, winter albedos of treeless areas are 10% to 50% higher than nearby forested areas because snow does not cover the trees as readily. Deciduous trees have an albedo value of about 0.15 to 0.18 whereas coniferous trees have a value of about 0.09 to 0.15.[8] Variation in summer albedo across both forest types is correlated with maximum rates of photosynthesis because plants with high growth capacity display a greater fraction of their foliage for direct interception of incoming radiation in the upper canopy.[46] The result is that wavelengths of light not used in photosynthesis are more likely to be reflected back to space rather than being absorbed by other surfaces lower in the canopy.

Studies by the Hadley Centre have investigated the relative (generally warming) effect of albedo change and (cooling) effect of carbon sequestration on planting forests. They found that new forests in tropical and midlatitude areas tended to cool; new forests in high latitudes (e.g., Siberia) were neutral or perhaps warming.[47]

Water

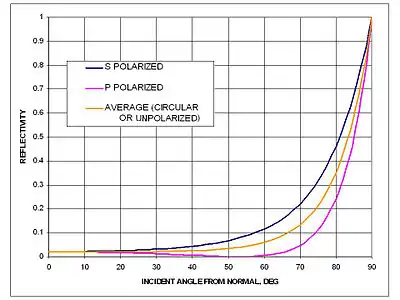

Water reflects light very differently from typical terrestrial materials. The reflectivity of a water surface is calculated using the Fresnel equations (see graph).

At the scale of the wavelength of light even wavy water is always smooth so the light is reflected in a locally specular manner (not diffusely). The glint of light off water is a commonplace effect of this. At small angles of incident light, waviness results in reduced reflectivity because of the steepness of the reflectivity-vs.-incident-angle curve and a locally increased average incident angle.[48]

Although the reflectivity of water is very low at low and medium angles of incident light, it becomes very high at high angles of incident light such as those that occur on the illuminated side of Earth near the terminator (early morning, late afternoon, and near the poles). However, as mentioned above, waviness causes an appreciable reduction. Because light specularly reflected from water does not usually reach the viewer, water is usually considered to have a very low albedo in spite of its high reflectivity at high angles of incident light.

Note that white caps on waves look white (and have high albedo) because the water is foamed up, so there are many superimposed bubble surfaces which reflect, adding up their reflectivities. Fresh 'black' ice exhibits Fresnel reflection. Snow on top of this sea ice increases the albedo to 0.9.

Clouds

Cloud albedo has substantial influence over atmospheric temperatures. Different types of clouds exhibit different reflectivity, theoretically ranging in albedo from a minimum of near 0 to a maximum approaching 0.8. "On any given day, about half of Earth is covered by clouds, which reflect more sunlight than land and water. Clouds keep Earth cool by reflecting sunlight, but they can also serve as blankets to trap warmth."[49]

Albedo and climate in some areas are affected by artificial clouds, such as those created by the contrails of heavy commercial airliner traffic.[50] A study following the burning of the Kuwaiti oil fields during Iraqi occupation showed that temperatures under the burning oil fires were as much as 10 °C colder than temperatures several miles away under clear skies.[51]

Aerosol effects

Aerosols (very fine particles/droplets in the atmosphere) have both direct and indirect effects on Earth's radiative balance. The direct (albedo) effect is generally to cool the planet; the indirect effect (the particles act as cloud condensation nuclei and thereby change cloud properties) is less certain.[52] As per Spracklen et al.[53] the effects are:

- Aerosol direct effect. Aerosols directly scatter and absorb radiation. The scattering of radiation causes atmospheric cooling, whereas absorption can cause atmospheric warming.

- Aerosol indirect effect. Aerosols modify the properties of clouds through a subset of the aerosol population called cloud condensation nuclei. Increased nuclei concentrations lead to increased cloud droplet number concentrations, which in turn leads to increased cloud albedo, increased light scattering and radiative cooling (first indirect effect), but also leads to reduced precipitation efficiency and increased lifetime of the cloud (second indirect effect).

Black carbon

Another albedo-related effect on the climate is from black carbon particles. The size of this effect is difficult to quantify: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that the global mean radiative forcing for black carbon aerosols from fossil fuels is +0.2 W m−2, with a range +0.1 to +0.4 W m−2.[54] Black carbon is a bigger cause of the melting of the polar ice cap in the Arctic than carbon dioxide due to its effect on the albedo.[55]

Human activities

Human activities (e.g., deforestation, farming, and urbanization) change the albedo of various areas around the globe. However, quantification of this effect on the global scale is difficult, further study is required to determine anthropogenic effects.[56]

Other types of albedo

Single-scattering albedo is used to define scattering of electromagnetic waves on small particles. It depends on properties of the material (refractive index); the size of the particle or particles; and the wavelength of the incoming radiation.

See also

References

- http://web.cse.ohio-state.edu/~parent.1/classes/782/Lectures/03_Radiometry.pdf

- Coakley, J. A. (2003). "Reflectance and albedo, surface" (PDF). In J. R. Holton; J. A. Curry (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Atmosphere. Academic Press. pp. 1914–1923.

- Henderson-Sellers, A.; Wilson, M. F. (1983). "The Study of the Ocean and the Land Surface from Satellites". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A. 309 (1508): 285–294. Bibcode:1983RSPTA.309..285H. doi:10.1098/rsta.1983.0042. JSTOR 37357. S2CID 122094064.

Albedo observations of the Earth's surface for climate research

- Environmental Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Thompson Gale. 2003. ISBN 978-0-7876-5486-3.

- Pon, Brian (30 June 1999). "Pavement Albedo". Heat Island Group. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "Thermodynamics | Thermodynamics: Albedo | National Snow and Ice Data Center". nsidc.org. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Alan K. Betts; John H. Ball (1997). "Albedo over the boreal forest". Journal of Geophysical Research. 102 (D24): 28, 901–28, 910. Bibcode:1997JGR...10228901B. doi:10.1029/96JD03876. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "The Climate System". Manchester Metropolitan University. Archived from the original on 1 March 2003. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- Tom Markvart; Luis CastaŁżer (2003). Practical Handbook of Photovoltaics: Fundamentals and Applications. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-85617-390-2.

- Tetzlaff, G. (1983). Albedo of the Sahara. Cologne University Satellite Measurement of Radiation Budget Parameters. pp. 60–63.

- "Albedo – from Eric Weisstein's World of Physics". Scienceworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Goode, P. R.; et al. (2001). "Earthshine Observations of the Earth's Reflectance". Geophysical Research Letters. 28 (9): 1671–1674. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28.1671G. doi:10.1029/2000GL012580.

- "MODIS BRDF/Albedo Product: Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document, Version 5.0" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "Snowball Earth: Ice thickness on the tropical ocean" (PDF). Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- "Effect of land albedo, CO2, orography, and oceanic heat transport on extreme climates" (PDF). Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- "Global climate and ocean circulation on an aquaplanet ocean-atmosphere general circulation model" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- Roman, M. O.; C.B. Schaaf; P. Lewis; F. Gao; G.P. Anderson; J.L. Privette; A.H. Strahler; C.E. Woodcock; M. Barnsley (2010). "Assessing the Coupling between Surface Albedo derived from MODIS and the Fraction of Diffuse Skylight over Spatially-Characterized Landscapes". Remote Sensing of Environment. 114 (4): 738–760. Bibcode:2010RSEnv.114..738R. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2009.11.014.

- Sicardy, B.; Ortiz, J. L.; Assafin, M.; Jehin, E.; Maury, A.; Lellouch, E.; Gil-Hutton, R.; Braga-Ribas, F.; et al. (2011). "Size, density, albedo and atmosphere limit of dwarf planet Eris from a stellar occultation" (PDF). European Planetary Science Congress Abstracts. 6: 137. Bibcode:2011epsc.conf..137S. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- Wm. Robert Johnston (17 September 2008). "TNO/Centaur diameters and albedos". Johnston's Archive. Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- Wm. Robert Johnston (28 June 2003). "Asteroid albedos: graphs of data". Johnston's Archive. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- Robert Roy Britt (29 November 2001). "Comet Borrelly Puzzle: Darkest Object in the Solar System". Space.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Matthews, G. (2008). "Celestial body irradiance determination from an underfilled satellite radiometer: application to albedo and thermal emission measurements of the Moon using CERES". Applied Optics. 47 (27): 4981–4993. Bibcode:2008ApOpt..47.4981M. doi:10.1364/AO.47.004981. PMID 18806861.

- Medkeff, Jeff (2002). "Lunar Albedo". Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- Mallama, Anthony; Krobusek, Bruce; Pavlov, Hristo (2017). "Comprehensive wide-band magnitudes and albedos for the planets, with applications to exo-planets and Planet Nine". Icarus. 282: 19–33. arXiv:1609.05048. Bibcode:2017Icar..282...19M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.09.023. S2CID 119307693.

- Mallama, Anthony (2017). "The spherical bolometric albedo for planet Mercury". arXiv:1703.02670. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Haus, R.; et al. (July 2016). "Radiative energy balance of Venus based on improved models of the middle and lower atmosphere" (PDF). Icarus. 272: 178–205. Bibcode:2016Icar..272..178H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.02.048.

- Earth Fact Sheet, NASA

- Mars Fact Sheet, NASA

- Li, Liming; et al. (2018). "Less absorbed solar energy and more internal heat for Jupiter". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3709. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3709L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06107-2. PMC 6137063. PMID 30213944.

- Hanel, R.A.; et al. (1983). "Albedo, internal heat flux, and energy balance of Saturn". Icarus. 53 (2): 262–285. Bibcode:1983Icar...53..262H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(83)90147-1.

- Pearl, J.C.; et al. (1990). "The albedo, effective temperature, and energy balance of Uranus, as determined from Voyager IRIS data". Icarus. 84 (1): 12–28. Bibcode:1990Icar...84...12P. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(90)90155-3.

- Pearl, J.C.; et al. (1991). "The albedo, effective temperature, and energy balance of Neptune, as determined from Voyager data". J. Geophys. Res. 96: 18, 921–18, 930. Bibcode:1991JGR....9618921P. doi:10.1029/91JA01087.

- Dan Bruton. "Conversion of Absolute Magnitude to Diameter for Minor Planets". Department of Physics & Astronomy (Stephen F. Austin State University). Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- Winston, Jay (1971). "The Annual Course of Zonal Mean Albedo as Derived From ESSA 3 and 5 Digitized Picture Data". Monthly Weather Review. 99 (11): 818–827. Bibcode:1971MWRv...99..818W. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1971)099<0818:TACOZM>2.3.CO;2.

- "The thawing Arctic threatens an environmental catastrophe". The Economist. 29 April 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- Schneider, Stephen Henry; Mastrandrea, Michael D.; Root, Terry L. (2011). Encyclopedia of Climate and Weather: Abs-Ero. Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-976532-4.

- Hall, D.K. and Martinec, J. (1985), Remote sensing of ice and snow. Chapman and Hall, New York, 189 pp.

- "All About Sea Ice." National Snow and Ice Data Center. Accessed 16 November 2017. /cryosphere/seaice/index.html.

- "Changing Greenland – Melt Zone" page 3, of 4, article by Mark Jenkins in National Geographic June 2010, accessed 8 July 2010

- "Health and Safety: Be Cool! (August 1997)". Ranknfile-ue.org. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Andrews, Rob W.; Pearce, Joshua M. (2013). "The effect of spectral albedo on amorphous silicon and crystalline silicon solar photovoltaic device performance". Solar Energy. 91: 233–241. Bibcode:2013SoEn...91..233A. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2013.01.030.

- Brennan, M.P.; Abramase, A.L.; Andrews, R.W.; Pearce, J. M. (2014). "Effects of spectral albedo on solar photovoltaic devices". Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 124: 111–116. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2014.01.046.

- Betts, RA (2000). "Offset of the potential carbon sink from boreal forestation by decreases in surface albedo". Nature. 408 (6809): 187–190. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..187B. doi:10.1038/35041545. PMID 11089969. S2CID 4405762.

- Boucher; et al. (2004). "Direct human influence of irrigation on atmospheric water vapour and climate". Climate Dynamics. 22 (6–7): 597–603. Bibcode:2004ClDy...22..597B. doi:10.1007/s00382-004-0402-4. S2CID 129640195.

- Bonan, GB (2008). "Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests". Science. 320 (5882): 1444–1449. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1444B. doi:10.1126/science.1155121. PMID 18556546. S2CID 45466312.

- Ollinger, S. V.; Richardson, A. D.; Martin, M. E.; Hollinger, D. Y.; Frolking, S.; Reich, P.B.; Plourde, L.C.; Katul, G.G.; Munger, J.W.; Oren, R.; Smith, M-L.; Paw U, K. T.; Bolstad, P.V.; Cook, B.D.; Day, M.C.; Martin, T.A.; Monson, R.K.; Schmid, H.P. (2008). "Canopy nitrogen, carbon assimilation and albedo in temperate and boreal forests: Functional relations and potential climate feedbacks" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (49): 19336–41. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10519336O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810021105. PMC 2593617. PMID 19052233. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Betts, Richard A. (2000). "Offset of the potential carbon sink from boreal forestation by decreases in surface albedo". Nature. 408 (6809): 187–190. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..187B. doi:10.1038/35041545. PMID 11089969. S2CID 4405762.

- "Spectral Approach To Calculate Specular reflection of Light From Wavy Water Surface" (PDF). Vih.freeshell.org. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- "Baffled Scientists Say Less Sunlight Reaching Earth". LiveScience. 24 January 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Travis, D. J.; Carleton, A. M.; Lauritsen, R. G. (8 August 2002). "Contrails reduce daily temperature range" (PDF). Nature. 418 (6898): 601. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..601T. doi:10.1038/418601a. PMID 12167846. S2CID 4425866. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- Cahalan, Robert F. (30 May 1991). "The Kuwait oil fires as seen by Landsat". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 97 (D13): 14565. Bibcode:1992JGR....9714565C. doi:10.1029/92JD00799.

- "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". Grida.no. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Spracklen, D. V; Bonn, B.; Carslaw, K. S (2008). "Boreal forests, aerosols and the impacts on clouds and climate" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 366 (1885): 4613–4626. Bibcode:2008RSPTA.366.4613S. doi:10.1098/rsta.2008.0201. PMID 18826917. S2CID 206156442.

- "Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis". Grida.no. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- James Hansen & Larissa Nazarenko, Soot Climate Forcing Via Snow and Ice Albedos, 101 Proc. of the Nat'l. Acad. of Sci. 423 (13 January 2004) ("The efficacy of this forcing is »2 (i.e., for a given forcing it is twice as effective as CO2 in altering global surface air temperature)"); compare Zender Testimony, supra note 7, at 4 (figure 3); See J. Hansen & L. Nazarenko, supra note 18, at 426. ("The efficacy for changes of Arctic sea ice albedo is >3. In additional runs not shown here, we found that the efficacy of albedo changes in Antarctica is also >3."); See also Flanner, M.G., C.S. Zender, J.T. Randerson, and P.J. Rasch, Present-day climate forcing and response from black carbon in snow, 112 J. GEOPHYS. RES. D11202 (2007) ("The forcing is maximum coincidentally with snowmelt onset, triggering strong snow-albedo feedback in local springtime. Consequently, the "efficacy" of black carbon/snow forcing is more than three times greater than forcing by CO2.").

- Sagan, Carl; Toon, Owen B.; Pollack, James B. (1979). "Anthropogenic Albedo Changes and the Earth's Climate". Science. 206 (4425): 1363–1368. Bibcode:1979Sci...206.1363S. doi:10.1126/science.206.4425.1363. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1748990. PMID 17739279. S2CID 33810539.

External links

| Look up albedo in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |