Oskar Schlemmer

Oskar Schlemmer (4 September 1888 – 13 April 1943) was a German painter, sculptor, designer and choreographer associated with the Bauhaus school.

Oskar Schlemmer | |

|---|---|

Oskar Schlemmer in a photograph by Hugo Erfurth (1920) | |

| Born | 4 September 1888 |

| Died | 13 April 1943 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, puppetry, theatre, dance |

| Movement | Bauhaus |

In 1923, he was hired as Master of Form at the Bauhaus theatre workshop, after working at the workshop of sculpture. His most famous work is Triadisches Ballett (Triadic Ballet), which saw costumed actors transformed into geometrical representations of the human body in what he described as a "party of form and colour".[1]

Biography

Childhood and apprenticeships

Born in September 1888 in Swabia, Germany,[2] Oskar Schlemmer was the youngest of six children. His parents, Carl Leonhard Schlemmer and Mina Neuhaus, both died around 1900 and the young Oskar lived with his sister and learned at an early age to provide for himself.[2] By 1903 he was completely independent and supporting himself as an apprentice in an inlay workshop, moving on to another apprenticeship in marquetry from 1905 to 1909.

Oskar Schlemmer studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in Stuttgart and won a scholarship to attend the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Stuttgart Academy of Fine Art), where he studied under the tutelage of landscape painters Christian Landenberger and Friedrich von Keller starting in 1906. In 1910 Schlemmer moved to Berlin where he painted some of his first important works before returning to Stuttgart in 1912 as the master pupil of abstract artist Adolf Hölzel, abandoning impressionism and moving toward cubism in his work. In 1914 Schlemmer was enlisted to fight on the Western Front in World War I until he was wounded and moved to a position with the military cartography unit in Colmar, where he resided until returning to work under Hölzel in 1918.[2]

The Bauhaus years

.jpg.webp)

In 1919 Schlemmer turned to sculpture and had an exhibition of his work at the gallery Der Sturm in Berlin.[3] At the same time he helped to update the curriculum at the Stuttgart Academy of Fine Art with the appointment of new faculty and exhibitions of modern art. Among those involved were Paul Klee and Willi Baumeister.[2] After his marriage to Helena Tutein in 1920, Schlemmer was invited to Weimar by Walter Gropius to run the mural-painting and sculpture departments at the Bauhaus School before taking over the stagecraft workshop from Lothar Schreyer in 1923.[4][3] His complex ideas were influential, making him one of the most important teachers working at the school at that time. However, due to the heightened political atmosphere in Germany at the end of the 1920s, and in particular with the appointment of the radical communist architect Hannes Meyer as Gropius's successor, in 1929 Schlemmer resigned his position and moved to take up a job at the Art Academy in Breslau.

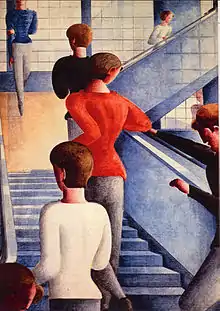

Schlemmer became known internationally with the première of his 'Triadisches Ballett' in Stuttgart in 1922. His work for the Bauhaus and his preoccupation with the theatre are an important factor in his work, which deals mainly with the problematic of the figure in space. People, typically stylised faceless female figures, continued to be the predominant subject in his painting. While at Bauhaus, he developed the multidisciplinary course "Der Mensch (The human being)." In the human form he saw a measure that could provide a foothold in the disunity of his time. After using Cubism as a springboard for his structural studies, Schlemmer's work became intrigued with the possibilities of figures and their relationship to the space around them, for example 'Egocentric Space Lines' (1924). Schlemmer's characteristic forms can be seen in his sculptures as well as his paintings. Yet he also turned his attention to stage design, first getting involved with this in 1929, executing settings for the opera 'Nightingale' and the ballet 'Renard' by Igor Stravinsky.

Life and death under the Third Reich

From 1928 to 1930, Schlemmer worked on nine murals for a room in the Folkwang Museum in Essen. After leaving the Bauhaus in 1929, Schlemmer took a post at the Akademie in Breslau, where he painted his most celebrated work, the 'Bauhaustreppe', ('Bauhaus Stairway') (1932; Museum of Modern Art, New York). He was obliged to leave the Breslau Academy when it was closed down in the wake of the financial crisis following the Wall Street Crash, and took up a professorship at Berlin's Vereinigte Staatsschulen für freie und angewandete Kunst (United State School for Fine and Applied Art) in 1932, which he held until 1933 when he was forced to resign due to pressure from the Nazis. The Schlemmers then moved to Eichberg near the Swiss border, and then to Sehringen before his pictures were displayed at the Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich in 1937. The last ten years of his life were spent in a state of 'inner emigration'. Max Bill, in his obituary of Schlemmer, wrote that it was 'as if a curtain of silence' had descended over him during this time.

During World War II, Schlemmer worked at the Institut für Malstoffe in Wuppertal, along with Willi Baumeister and Georg Muche, run by the philanthropist Kurt Herbert. The factory offered Schlemmer the opportunity to paint without the fear of persecution. His series of eighteen small, mystical paintings entitled "Fensterbilder" ("Window Pictures," 1942) were painted while looking out the window of his house and observing neighbors engaged in their domestic tasks. These were Schlemmer's final works before his death in the hospital at Baden-Baden in 1943.

Legacy

Schlemmer's ideas on art were complex and challenging even for the progressive Bauhaus movement. His work, nevertheless, was widely exhibited in both Germany and outside the country. His work was a rejection of pure abstraction, instead retaining a sense of the human, though not in the emotional sense but in view of the physical structure of the human. He represented bodies as architectural forms, reducing the figure to a rhythmic play between convex, concave and flat surfaces. And not just of its form, he was fascinated by every movement the body could make; trying to capture it in his work. As well as leaving a large body of work behind, Schlemmer art theories have also been published. A comprehensive book of his letters and diary entries from 1910 to 1943 is also available.

Along with Schlemmer's diary, his private letters to Otto Meyer and Willi Baumeister have given valuable insight on what happened at the Bauhaus; especially his writings of how the staff and students responded to the many changes and developments at the school.

Schlemmer's first retrospective in the United States was mounted by the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1986.[5]

On 4 September 2018, to commemorate what would have been his 130th birthday, Google released a Google Doodle celebrating him.[6]

Controversy

In 2000, the artist's daughter Ute Jaina Schlemmer, who asserted that she owns the painting Bauhaus Stairway (Bauhaustreppe) or is owed money for it, obtained a court order to hold it for further investigation while it was on temporary loan from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Before the injunction was served on the Neue Nationalgalerie, Bauhaus Stairway had already been packed and shipped to New York.[7]

Art market

In 1998, Schlemmer's Idealistic Encounter (1928) was sold for $1.487 million at Sotheby's in New York.[8]

References

- "Oskar Schlemmer's ballet of geometry – in pictures". The Guardian. 24 November 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Artrepublic". artrepublic.com. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Oskar Schlemmer Biography – Infos – Art Market". oskar-schlemmer.com. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Bauhaus100. Workshops. Stagecraft. Retrieved 6 December 2018

- Wilson, William (14 September 1986). "Oskar Schlemmer: Bauhaus' Mr. Clean". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Oskar Schlemmer's 130th Birthday". Google. 4 September 2018.

- Dobrzynski, Judith H. (10 February 2000). "Modern Is Focus Of a New Dispute Over a Painting". The New York Times. p. 3. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Melikian, Souren (16 May 1998). "Price Is Right for Signature, Size and Subject: The Market Gets a Second Wind". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Oskar Schlemmer. |

- Oskar Schlemmer The Official Site

- Volker Straebel's essay on 'The Mutual Influence of Europe and North America in the History of Musikperformance' / Oskar Schlemmer's Triadisches Ballett

- Oskar Schlemmer at Find a Grave

- Articles on Bauhaustreppe (1932) in The Burlington Magazine (July 2009; second part September 2010) by John-Paul Stonard

- Quem foi Oskar Schlemmer e porque a Google lhe dedica um Doodle (Portuguese)