Ottoman Army (1861–1922)

The Ottoman Army was reorganized along modern Western European lines during the Tanzimat modernization period and functioned during the decline and dissolution period that is roughly between 1861 (though as a unit First Army dates 1842) and 1918, end of World War I for the Ottomans. The last reorganization occurred during the Second Constitutional Era.[1]

| Modern Ottoman Army | |

|---|---|

| Turkish: Modern Osmanlı Ordusu | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Active | 1842/1861 – 1922 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Army |

| Size | 2,870,000 (1918) |

| Garrison/HQ | Istanbul |

| Patron | Monarch |

| Engagements | World War I, Battle of Gallipoli, Arab Revolt, Tripolitanian War, Balkan Wars |

| Commanders | |

| Sultan | Mehmed V |

| Minister of War | Ismail Enver Pasha |

| Notable commanders | Mustafa Kemal Atatürk |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| Military of the Ottoman Empire |

.svg.png.webp) |

| Conscription |

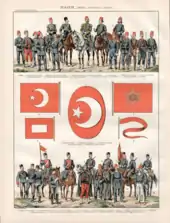

The uniforms of the modern army tended to reflect the uniform of those countries who were the principal advisors to the Ottoman army at the time. The Ottoman government considered adopting western-style headdress for all personnel within the army, but the fez was favoured because of its user friendliness during the postures of the Islamic ritual prayer.

French-style uniform and court dress were common during the early stage of the Tanzimat modernization period. After the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, which forced the Ottoman government to search for other role models, German and British style uniforms became popular. During World War I, the officer uniforms were mainly based on the German model. The Crimean War was the first war effort in which the modern army took part, profiling itself as a decent force.

Establishment of the modern army

The shift from the Classical Army (1451–1606) took more than a century, beginning from failed attempts of Selim III (r. 1789–1807) and Alemdar Mustafa Pasha (1789), traversing a period of Ottoman military reforms (1826–1858) and finally reaching the period of Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876–1909). As early as 1880 Abdul Hamid sought German assistance, which he secured two years later, culminating in the appointment of Lt. Col. Otto Köhler.[2][3] Although the consensus that Abdul Hamid II favored the modernization of the Ottoman army and the professionalization of the officer corps was fairly general, it seems that he neglected the military during the last fifteen years of his reign, and he also cut down the military budget. The formation of the modern Ottoman army proved a slow process with ups and downs.

1842–1861

.tiff.jpg.webp) Resembling the French line-infantry uniform

Resembling the French line-infantry uniform.tiff.jpg.webp) French-inspired palace guard dress

French-inspired palace guard dress_image_4th_in_collection_of_4_col._lith._pl._by_Riffault_after_Raffet%253B_three_uniform_figures_of_Turkish_infantrymen%252C_standing%252C_with_more_in_background..jpg.webp) Ottoman soldiers, 1854

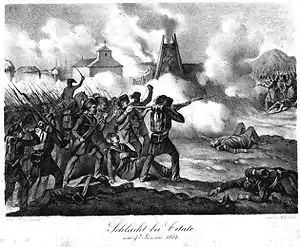

Ottoman soldiers, 1854 Ottoman and Russian forces during the Battle of Cetate of 1853-1854

Ottoman and Russian forces during the Battle of Cetate of 1853-1854 Distribution of the Medjidie, after the Battle of Cetate, 1854

Distribution of the Medjidie, after the Battle of Cetate, 1854 Landing of the Ottoman army at Eupatoria, E. Morier, 1855

Landing of the Ottoman army at Eupatoria, E. Morier, 1855

1861–1896

.tiff.jpg.webp) Resembling the Imperial German Army dunkelblau uniform

Resembling the Imperial German Army dunkelblau uniform.tiff.jpg.webp) Officer of the general staff wearing the Imperial German Army dunkelblau uniform

Officer of the general staff wearing the Imperial German Army dunkelblau uniform.tiff.jpg.webp) Note the French-inspired Zouave uniform on the right

Note the French-inspired Zouave uniform on the right.tiff.jpg.webp) German-inspired dunkelblau uniforms

German-inspired dunkelblau uniforms.tiff.jpg.webp) German-inspired dunkelblau uniforms

German-inspired dunkelblau uniforms.tiff.jpg.webp) German-inspired dunkelblau uniforms

German-inspired dunkelblau uniforms.tiff.jpg.webp) German-inspired dunkelblau uniforms, and a French-inspired Zouave uniform

German-inspired dunkelblau uniforms, and a French-inspired Zouave uniform.tiff.png.webp) Resembling the Imperial German naval uniform

Resembling the Imperial German naval uniform_(NYPL_b14896507-416367).tiff.png.webp) Resembling the Imperial German naval uniform

Resembling the Imperial German naval uniform.tiff.jpg.webp) Fire-department personnel wearing the German dunkelblau uniform, and a variant of the fez which resembles the German Pickelhaube

Fire-department personnel wearing the German dunkelblau uniform, and a variant of the fez which resembles the German Pickelhaube.tiff.jpg.webp) Resembling the Prussian artillery uniform

Resembling the Prussian artillery uniform.tiff.jpg.webp) Resembling the Prussian artillery uniform

Resembling the Prussian artillery uniform.tiff.jpg.webp) Resembling the Prussian Uhlan regiment uniform

Resembling the Prussian Uhlan regiment uniform The Imperial Ottoman Army in 1900

The Imperial Ottoman Army in 1900

Engagements

Notable Commanders

Units

Infantry

Infantry were the backbone of the army. Ottoman infantry were assigned the function of infiltrating enemy lines and protecting territory gained.

Cavalry

The cavalry was losing its efficiency in the late 19th and early 20th century. There were three cavalry units, 1 Cav., 2 Cav., and 3 Cav. These units were the successors to the Hamidiye cavalry formations, which were disestablished on August 17, 1910. These new regiments were formed into seven cavalry brigades and three independent regiments and were composed mainly of Kurds, some rural Ottomans and an occasional Armenian.

Hamidiye light cavalry

1892 was the first time a trained and organized Kurdish force was encouraged by the Sultan, Abdul Hamid II, Hamidiye (cavalry). There were several reasons as to why the Hamidiye light cavalry was created. They were intended to be modeled after the Caucasian Cossack Regiments (example Persian Cossack Brigade) and were first to patrol the Russo-Ottoman frontier[4] The Hamidiye Cavalry was in no way a cross-tribal force, despite their military appearance, organization and potential.[5] Hamidiye quickly found out that they could only be tried through a military court-martial.[6] They became immune to civil administration. Realizing their immunity, they turned their forces into “legalized robber brigades” as they stole grain, harvested fields not of their possession, drove off herds and openly stole from shopkeepers.[7]

In 1908, after the overthrow of Sultan, the Hamidiye Cavalry was disbanded as an organized force but as they were “tribal forces” before official recognition, they stayed as “tribal forces” after dismemberment. The Hamidiye Cavalry is described as a military disappointment and a failure because of its contribution to tribal feuds.[8]

The decision to disband was after the 1908 revolution and all of the units returned to their tribes by August 17, 1910. Militarily, Ottoman General Staff stated conventional-style military discipline had always been a problem with these units which were replaced of the new reserve cavalry formations.[9]

Artillery

After the Balkan wars, Ottoman armies began to deploy rapid-firing guns. Artillery began to gain importance and dominated the battlefield.

Engineering

The engineering branch has two main functions. Supportive functions are removal of the physical obstacles created by the enemy, to repair the damaged bridges and facilities, building bridges and other infrastructure that enable infantry operations. Offensive functions are creating obstacles to slow down the enemy, and demolishing infrastructure. Each corps had an engineering battalion and each division had an engineering company.

Communication

The communication branch was established in 1882. Its designation was 'telegraph battalion' and its main function was to operate telegraphs. In 1910 telephone was added to its functions. In 1911 wireless stations were added to the unit. For the first time, in 1911 during the war with Italy, a direct line between Izmir and Derne was established. Beginning 1912, Balkan wars, every Corp level unit had a 'telegraph battalion.'

Medical

The medical branch does not have a precise date. During 1908, second constitutional period, its structure included doctors, surgeons, veterinaries, pharmacists, dentists, chemists, wound-dressers and nurses. They were organized by the Health department of the Ministry of War.

Military bands

Since the early times, each regiment had its own band. In 1908, second constitutional period, there were 35 military bands in Capitol. Each army had two bands. The “Imperial Band” (mızıka-i humayun) consisted of 90 musicians.

Paramilitary units

The Turkish Gendarmerie was a unit which was employed on police duties (police duties among civilian populations). Gendarmerie was a paramilitary unit because it was not included as part of a state's formal armed forces. It was established in 1903. Organized under infantry gendarmerie and the cavalry gendarmerie. These were small units. The largest unit was the regiment. They were distributed across the administrative units under Valis. The number changed with the security needs.

From a historical perspective, there was a Gendarmerie performing the same functions before 1903. Since the term Gendarmerie was noticed only in the Assignment Decrees published in the years following the Edict of Gülhane in 1839, it is assumed that the Gendarmerie organization was founded after that year, but the exact date of 'unit foundation' is not that date. Historically, there is also a manual,Asâkir-i Zaptiye Nizâmnâmesi, which was adopted on June 14, 1869, which is accepted as the organizational foundation.[10] After the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War, Ottoman grand vizier Mehmed Said Pasha decided to establish a modern law enforcement organization, and a military mission (military missions section) is formed for this task. After the Young Turk Revolution in 1908, the Gendarmerie achieved great successes, particularly in Rumelia.

In 1909, the Gendarmerie was affiliated with the Ministry of War, and its name was changed to the Gendarmerie General Command (Ottoman Turkish: Umûm Jandarma Kumandanlığı). During World War One, especially after Battle of Sarikamish, Gendarmerie units changed hand from Vali'es (civilian authority) to War Ministry (military authority) to be combatant branch. This change effectively defined them combat units.

Organization

After the Second Constitutional Era, 1908, the Ottoman General Staff published the “Regulation on Military Organisation.” It was adopted on July 9, 1910. Army commands were replaced by “army inspectorates” whose main responsibility was training and mobilization. The army was to be composed of three parts: regular army (nizamiye), reserve army (redif) and the home guard (müstahfız). The “corps” concept was established. Reserve divisions were to be combined into reserve corps and they were to be given artillery units. Units of the regular army would recruit soldiers through the sources of the army inspectorate they belonged to.

The strengths of the Ottoman army were at the highest echelons of its rank structure.[11]

Unlike the British or the Germans, the Ottomans had no long service corps of professional non-commissioned officers, which created the weakest point.[11]

Divisions

An infantry division was to be composed of three infantry regiments, a sharpshooter battalion, a field artillery regiment and an army band. Divisions had operations, intelligence, judiciary, supplies, medical and veterinary departments.

Corps

Corps were composed of three divisions and other ancillary units. Corps had operations, personnel, judiciary, supplies, secretariat, veterinary, documentation, artillery, engineering and post divisions. Corps consist of 41,000 enlisted and 6,700 animals.

During this period, not based on chronological order, the corps that were established: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX, XXI, XXII, XXV, Iraq Area, Halil, I Kaf., II Kaf., Hejaz

Fortified zones

Fortified zones had the same departments of divisions. They added documentation, artillery, engineering, communications and floodlight projectors.

During this period, not based on chronological order, the fortified zones that were established: Dardanelles, Bosporus, Chataldja, Adrianople, Smyrna, Erzurum, Kars

Army

Army headquarters had corps level departments and also infantry department, cavalry department and field gendarmerie department.

- The 1st Army was formed on September 6, 1843[12]

- The 2nd Army was originally formed in 1873.[12]

- The 3rd Army was originally formed in the Balkans and headquarters was at Salonica.

- The 4th Army Army was originally formed in the Anatolia.

- The 5th Army was formed on March 24, 1915 and assigned the responsibility of defending the Dardanelles straits in World War I.

- The 6th Army was formed in 1877 and it was stationed in Baghdad.

Army Group

This construct developed late in World War I. The conflicts depleted the Army units. By uniting the Armies, Army Groups was used to compensate for the lost units and keep the remainder functioning.

In August 1917, the Caucasus Army Group was established. It was a unification of Second and Third Armies. In July 1917, the Yildirim Army Group was established. It was a unification of Sixth and Seventh Armies. In June 1918, the Eastern Army Group was established. This unit is composed of whatever left from Caucasus Army Group (united under third) and the Ninth Army.

General Staff

General Staff was the group of officers who were responsible for the administrative, operational and logistical needs. The general staff fulfilled the classic staff duties then in use by all major European powers and was staffed by trained general staff officers, who were selected and trained in staff procedures at the War Academy in Constantinople. After completion of the War Academy, graduates were advanced in grade over their non-graduate contemporaries and immediately assigned to key billets in the army. The staff was supervised by a chief of staff and was composed of various divisions, which specialized in a variety of military fields. The most influential staff division was the Operations Division. Staff provided bi-directional flow of information between a commanding officer and subordinate units.

In the Ottoman Army, staff officers in all levels were combatants, which is a comparison to other armies that have enlisted personal for specific tasks that were not combatant. Before the Second Constitutional Era, the Sultan and his high-ranking staff officers performed the main planning and activity by the Ministry of War which was established in 1826. During this time, the General Staff was a department within the Ministry of War. It performed the recruitment, reserves, judiciary and printing military charts. Ahmed Izzet Pasha, who became the chief of general staff on August 15, 1908, was aware of the urgent need of this institution to be reformed. Ahmed Izzet Pasha's work produced good results and he managed to provide a better and much more efficient structure for the General Staff. At the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, the General Staff was divided into seven departments and it formed the headquarters of Nazım Paşa, the acting head commander. When the war was lost, further changes were needed and these came with Enver Pasha, who on January 3, 1914 replaced Ahmed Izzet Pasha as both the minister of war and the chief of general staff.

During the course of the World War, the Ottoman General Staff had seven departments: operations, intelligence, railroads, education, military history, personnel and documentation.

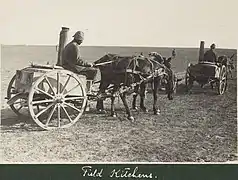

Force sustainment

LoCI was modeled on a German organizational architecture. German organization was designed to operate at friendly rear areas. Neither Ottoman nor German LoCIs were staffed or equipped to do much more than coordinate logistics and transport supplies.[13]

The history of the Transportation starts with World War I. World War I Ottoman logistics system was a pipeline that moved men and supplies from rear areas to forward stations and further distribution to front-line corps and infantry divisions. 279 officers, 119 doctors, and 12,279 men were assigned at the onset but by April 14, 1915, few of these were available for point or area security.[14]

Under heavy insurgency “protected logistics areas” were created for both convoys and for fixed facilities such as hospitals and magazines. The idea of protected logistics areas were carried from the Ottoman Classical Army. The protected logistic areas, when plotted on a map, gave the heavy insurgency points. These were established along the Sivas-Erzurum corridor, which carried the bulk of the Third Army's supplies. and along the Trabzon-Erzurum corridor, which carried the army's magazine capacity.[14]

The weak road network within the Third Army area was rapidly deteriorating in 1914. Every province had civilian road workers and they were not enough to maintain the all-weather roads. The combatant units would not last more than couple days without the logistic support. Increased need required the army to build up its labor services, which did transfer resources from allocated units to combat to sustain the front. During World War I, European armies had ten logistic persons for one combatant.

The Ottoman labour services (amela taburu) were noncombat, so they were unarmed, as in the other armies. They had only six labour service battalions in 1914. In 1915, these were reorganized and expanded to 30 battalions of which 11 (33%) were deployed on the Erzincan-Erzurum-Hasankale-Tortum corridor. In 1915 the labour battalions were an essential and absolute requirement for the function of Third Army.[15] Attrition wore the combat battalions down, but World War I was also hard on the non-combatant units. During 1916 at the high point of the Russian advance, the labor battalions were targeted. In the summer of 1916, the surviving 28 (out of 33) labor battalions were reorganized into 17 (full strength) battalions.

Chief of General Staff

General Staff was organized under Chief of General Staff.

- Ahmed Izzet Pasha from August 15, 1908 to January 1, 1914

- Enver Pasha from January 3, 1914 to October 4, 1918

- Ahmed Izzet Pasha October 4, 1918 to November 3, 1918

- Cevat Pasha from November 3, 1918 to December 24, 1918

- Fevzi Pasha from December 24, 1918 to May 14, 1919

- Cevat Pasha from May 14, 1919 to August 2, 1919

- Hadi Pasha from August 2, 1919 to September 12, 1919

- Fuad Pasha from September 12, 1919 to October 9, 1919

- Cevat Pasha from October 9, 1919 to February 16, 1920

- Shevket Turgut Pasha from February 16, 1920 to April 19, 1920

- Nazif Pasha from April 19, 1920 to May 2, 1920

- Hadi Pasha from May 2, 1920 to May 19, 1920

Ministry of War (War Department)

The apex of the Ottoman military structure was the Ministry of War, which had been established in 1826 with the Auspicious Incident, and had transformed a couple of times during the Ottoman military reforms. Within the ministry there were offices for procurement, combat arms, peacetime military affairs, mobilization, and for promotions.

Special Organization

The Special Organization was a special forces unit established in 1913.[16] It was an organization designed to establish insurgency and, second, function as an intelligence service.[16] Instigating insurgency, conducting espionage in foreign countries, and counterespionage inside the Ottoman Empire was the function between 1913 and 1918.[lower-alpha 1] The institutional origin, the reason given in the strategic document, was related to the unsatisfactory result of the First Balkan War and the goal was the recovery of Edirne.[17] This military organization had no precedent in Ottoman history, and it was developed direct interaction out of the counterinsurgency experiences from Macedonia and the guerrilla experiences from Libya with a handful of Ottoman officers.[17] Difference between the secret service of Abdulmamit II[lower-alpha 2] was directly linked to him and did not have operational function.[lower-alpha 3] There is a controversy of burned intelligence documents of special forces, which Shaw puts the event in 1914 not later.[18] That was the day Enver became war minister and destroyed Abdul Hamid's records, probably Abdul Hamid's intelligence on him. The first field operator was Süleyman Askeri, who undertook the first mission and established the field structure.[17] No actual evidence to support any claims of a dual-track structure, which means operated with both political and military goals.[17] Managed singlehandedly by Süleyman Askeri Bey from foundation to November 1914. The organization sub-management consisted of Atif Bey (Kamçil), Aziz Bey, Dr. Bahattin Sahakir, and Dr. Nazim Bey .[lower-alpha 4] Staff was organized four departments: the European Section headed by Arif Bey, the Caucasian Section headed by Captain Reza Bey, the Africa and Libya Section headed by Hüseyin Tosun Bey, and the Eastern Provinces Section headed by Dr. Sakir and Rueni Bey.[19] The headquarter was on Nur-i Osmariiye Street in Constantinople.

War Council

The War Council was under the Ministry of War. Established by the high-ranking staff officers during wartime, the head of the council was the Sultan.

After 1908, the Ministry of War became part of the Imperial Government. In 1908, the Ministry of War's powers (high-ranking staff officers) moved to the War Council, and the War Council was abolished when Enver Pasha became the minister of war. The Sultan's group of high-ranking staff officers were silently removed from control. Finally, the Ministry of War became part of a civilian structure, which left the General Staff to a military establishment.

Minister of War (Nazir-i Harbiye)

The titular Commander-in-Chief of the Ottoman military forces was the Sultan. However, the Minister of War fulfilled as the commander of the military forces. During wartime, the Minister of War was the overall commander, corresponding to the command of the Ottoman Army.

- Ömer Rüştü Pasha from July 23, 1908 to August 7, 1908

- Recep Pasha from August 7, 1908 to March 4, 1909

- Ali Rıza Pasha from March 4, 1909 to April 28, 1909

- Salih Hulusi Pasha from April 28, 1909 to January 12, 1910

- Mahmud Shevket Pasha from January 12, 1910 to July 9, 1912

- Hurshid Pasha from July 9, 1912 to July 29, 1912

- Nazim Pasha from July 29, 1912 to January 22, 1913

- Mahmud Shevket Pasha January 23, 1913 to June 11, 1913

- Ahmed Izzet Pasha June 18, 1913 to October 5, 1913

- Curuksulu Mahmud Pasha 5 October 1913 – 3 January 1914)

- Enver Pasha from January 3, 1914 to October 4, 1918

- Ahmed Izzet Pasha from October 14, 1918 to November 11, 1918

- Kölemen Abdullah Pasha from November 11, 1918 to December 19, 1918

- Cevat Pasha from December 19, 1918 to January 13, 1919

- Ömer Yaver Pasha (January 13, 1919 – February 24, 1919)

- Ali Ferid Pasha (February 24, 1919 – March 4, 1919)

- Abuk Ahmet Pasha (March 4, 1919 – April 2, 1919)

- Mehmet Şakir Pasha (April 2, 1919 – 19 May 1919)

- Şevket Turgut Pasha (May 19, 1919 – June 29, 1919)

- Ali Ferid Pasha (29 May 1919 – 21 July 1919)

- Nazım Pasha (July 21, 1919 – August 13, 1919)

- Süleyman Şefik Pasha (August 13, 1919 – October 2, 1919)

- Cemal Pasha (October 2, 1919 – January 21, 1920)

- Salih Hulusi Pasha (January 21, 1920 – February 3, 1920)

- Mustafa Fevzi Pasha (February 3, 1920 – April 5, 1920)

- Damat Ferid Pasha (Acting) (April 5, 1920 – June 10, 1920)

- Ahmet Hamdi Pasha (10 June 1920 – 30 July 1920)

- Hüseyin Hüsnü Pasha (July 31, 1920 – October 21, 1920)

- Çürüksulu Ziya Pasha (October 21, 1920 – November 4, 1922)

Personnel

The modern army simplified the rank structure, but the rank system was very complex.

At the onset of the Second Constitutional Era in 1908, among the officers there were lieutenants who were 58 years old, captains who were 65 years old and majors who were 80 years old. In 1909 reformation age limits were set (41 for lieutenant, 46 for captains, 52 for majors, 55 for lieutenant colonels, 58 for colonels, 60 for brigadier generals, 65 for generals and 68 for field marshals)

Commissioned officers

| Military ranks | |

|---|---|

| Ottoman ranks |

Western equivalents |

| Officers | |

| Müşir | Field marshal |

| Birinci Ferik (Serdar) | General |

| Ferik | Lieutenant general |

| Mirliva | Major general |

| Miralay | Brigadier |

| Kaymakam | Colonel |

| Binbaşı | Lieutenant colonel |

| Kolağası | Major |

| Yüzbaşı | Captain |

| Mülâzım-ı Evvel | First lieutenant |

| Mülâzım-ı Sani | Second lieutenant |

Enlisted personnel

In 1908, active duty lengths were set at two years for the infantry, three years for other branches of the Army and five years for the Navy. During the course of the World War, these remained largely theoretical.

| Military ranks | |

|---|---|

| Ottoman ranks |

Western equivalents |

| Non-commissioned officers | |

| Çavuş | Sergeant |

| Onbaşı | Corporal |

| Soldiers | |

| Nefer | Private |

The uniform of a serasker, the highest military rank of the Ottoman Empire

The uniform of a serasker, the highest military rank of the Ottoman Empire Army general Mehmed Şakir Pasha

Army general Mehmed Şakir Pasha Conscripted naval cadet Fuat Hüsnü Kayacan

Conscripted naval cadet Fuat Hüsnü Kayacan Naval uniform (pictured Hüseyin Hüsnü Pasha)

Naval uniform (pictured Hüseyin Hüsnü Pasha) Admiral Hasan Rami Pasha

Admiral Hasan Rami Pasha Naval uniforms

Naval uniforms

Training

In the Ottoman Army, the commissioned officers who receive training relating to their specific military occupational specialty or function in the military called mektepli (educated) officers. There were also commissioned officers who did not receive training, but were put through serving at the ranks at specific periods of time. These commissioned officers were called alaylı. The Ottoman Empire tried to replace alaylı with mektepli officers. A majority of the officers were alaylı. Princes (by birth) and important statesmen (by position) were considered as officers without having received military training or worked through ranks. It is also true that this group may have training on leadership (viziers, governors, etc.) and management generalists (medicine, engineering, etc.).

Ottoman Military Academy

The Academy was formed in 1834 by Mehmed Namık Pasha and Marshal Ahmed Fevzi Pasha as the Mekteb-i Harbiye ("War School"), and the first class of officers graduated in 1841. Its formation was a part of the military reforms within the Ottoman Empire as it recognized the need for more educated officer s to modernize its army.

Ottoman Armed Forces College

The Ottoman Armed Forces College was founded in 1848. It was renamed the Armed Forces College in 1964.

Ottoman Military College (Staff Officers)

In order to train Staff Officers in the same system as European armies, the 3rd and 4th years were created in the War Academy under the name of “Imperial War School of Military Sciences" General Staff Courses” in 1848. Abdülkerim Pasha was appointed as the first director of these courses. As part of the reorganization efforts of the Ottoman Army, new arrangements were implemented in 1866 for the Staff College and other Military Schools. Through these arrangements, the General Staff training was extended to three years, and with additional military courses a special emphasis was placed on exercises and hands-on training. Although being a staff officer was initially considered as a different military branch in itself, effective from 1867 new programs were implemented to train staff officers for branches like infantry, cavalry and artillery. In 1899, a new system was developed on the basis of the view that the General Staff Courses should train more officers with higher military education in addition to Staff Officers’ training. Following this principle, a greater number of officers from the Army War Academy began to be admitted to the Staff College. This process continued until 1908. Following the declaration of the Second Constitutional Period, the structure of the Staff College was rearranged with a new Staff College Regulation dated 4 August 1909. The new designation “General Staff School” passed in October,

With General Staff School, the practice of direct transition from Army War Academy to Staff College was abolished, and admission into Staff College now required two years of field service following the Army War Academy. Afterward, the officers were subjected to examinations, and those who passed the exam were admitted into the college as Staff Officer candidates. Following the Allied occupation of Constantinople on 16 March 1920, military schools were dissolved by the victors of the First World War; nevertheless, the Staff College was managed to continue its activities until April 1921 at the Şerif Pasha Mansion in Teşvikiye, Constantinople where it had been moved on 28 January 1919. Since all instructors and students went to Anatolia to join the National War of Independence, the Staff College was closed down.

Military missions

The French military system was used before the modern Ottoman Army developed. After defeated by Russia in the war of 1877–78, the Ottoman's reform process commenced with a fundamental revision. The German military system replaced the French one. The first German military mission arrived in Capitol in 1882. It was headed by a cavalry officer named Koehler. He was appointed as his aide-de-camp.

There were three military missions active at the turn of 1914. These were the British Naval Mission led by admiral Limpus, the French Gendarme Mission led by general Moujen, and the German Military Mission led by Goltz.

British military mission

British military advisors, which were mainly naval, had rather less impact on the Ottoman navy.[20] The British naval mission established in 1912 under admiral Arthur Limpus. He was recalled in September 1914 due to increasing concern Britain would soon enter the war. The military mission of reorganizing the Ottoman Navy was taken over by rear admiral Wilhelm Souchon of the Imperial German Navy. An interesting note regarding the symbolism; the Ottoman ships painted the same colors as those of the Royal Navy, and the officer insignia mirrored that of the British.[21]

The British Naval Mission was led by:

- Admiral Douglas Gamble (February 1909 – March 1910)

- Admiral Hugh Pigot Williams (April 1910 – April 1912)

- Admiral Arthur Limpus (April 1912 – September 1914)

French military mission

French military advisors were very effective. A fledgling air force began in 1912, its history began under the Ottoman Aviation Squadrons. A complete overhaul of the provincial gendarme was also a part of the French military mission.[20] The French gendarme mission was led by General Moujen.

German military mission

The German military mission became the third most important command center (Sultan, Minister of War, Head of Mission) for the Ottoman Army.

The German mission was accredited from 27 October 1913 to 1918. General Otto Liman von Sanders, previously commander of the 22nd Division, was assigned by the Kaiser to Constantinople.[22][23] Germany considered an Ottoman-Russian war to be imminent, and Liman von Sanders was a general with excellent knowledge of the Russian armed forces. The Ottoman Empire was undecided about which side to take in a future war involving Germany, Britain and France. The 9th article of the German Military Mission stated that in case of a war the contract would be annulled.

The German military mission eventually became the most important among the military missions. The history of German-Ottoman military relations went back to the 1880s. Grand Vizier Said Halim Pasha and Minister of War Ahmed Izzet Pasha were instrumental in developing initial relations. Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz to establish the first German mission. General Goltz served two periods within two years. In early 1914, the Ottoman Minister of War was a former military attaché to Berlin, Enver Pasha. About the same time, General Otto Liman von Sanders, was nominated to the command of the German 1st Army. The 1st Army was the largest one located on the European side.

Military culture

H. G. Dwight relates witnessing an Ottoman military burial in Constantinople and took pictures of it. H. G. Dwight says that the soldiers were from every nation (ethnicity), but they were only distinguished by their religion, in groups of "Mohammedans" and "Christians". The sermons were performed as based on the count of Bibles, Korans, and Tanakhs in provenance of the battlefield. This is what the caption of one slide reads (on the right):

One officer was left, who made to the grave-diggers and spectators a speech of moving simplicity. "Brothers," he said, "Here are men of every nation - Turks, Albanians, Greeks, Bulgarians, Jews; but they died together, on the same day, fighting under the same flag. Among us, too, are men of every nation, both Mohammedan and Christian; but we also have one flag and we pray to one God. Now, I am going to make a prayer, and when I pray let each one of you pray also, in his own language, in his own way.

Equipment

Sultan Abdul Hamid II became aware of the need to renew the weapons of the army in the late 19th century. This coincides with the European arms industries were in rapid progress. The Ottoman Army had only obsolete weapons with low efficiency. Abdul Hamid II removed the old system, but only an insignificant munitions industry developed. As a consequence, Ottoman Army relied on imports and grants from its allies for its needs of weapons and equipment. The situation is only improved with the decree issued on July 3, 1910 which included the budget for purchases of arms and ammunition.

Weapons

General Vidinli Tevfik Paşa, was sent to Germany to analyse, select, and purchase Mauser rifles. Instead of the offered rifles (Mauser M1890), the Ottomans bought the Mauser M1893 and M1903 in 7.65 mm caliber. In 1908, when constitutional rule was restored, the Ottoman Army had mostly basic rifles and only a few rapid-firing ones.

The Ottoman Army had no machine gun units until early 1910 (the changes implemented on July 3, 1910). The available ones were used in warships and for coastal defense. The few machine guns were all Maxim-Nordenfeld Maxim gun (MG09 version). Following years only a handful of Hotchkiss M1909, Schwarzlose MG M.07/12 added.

In 1914 officers had mainly Browning M1903, Mauser C96 and also in some quantity Beholla, Frommer M912, Luger P08, Smith & Wesson No. 3

Infantry used two different kinds of grenades. The most commonly used offensive grenade was the German stick grenade M1915 and M1917 Stielhandgranate. There were also defensive grenades used were "ball" and "egg" shaped.

The most common types of Ottoman field guns during WWI were German-designed and manufactured 75-mm Krupp M03 L/30 Field Gun, 77-mm Krupp M96 L/27 nA and the 77-mm Rheinmetall M16 L/35 guns. Desperately short of field artillery, the Ottoman Army also used a lot of older and obsolescent field guns, some dating back to the 1870s, as well as captured Russian and British guns[24]

Vehicles

Uniforms

Bayonets were made by German companies in Solingen and Suhl.

Disposition of Units

1908

Disposition of the forces in 1908. First Army was in Constantinople and the Bosporus, also units in Europe and Asia Minor. The First Army also had inspectorate functions for four Redif (reserve) divisions:[25] The Second Army headquarter established in Adrianople. Its operational area was Thrace, the Dardanelles, and it had units in Europe and Asia Minor.[26] The Second Army also had inspectorate functions for six Redif (reserve) divisions and one brigade:[25] Third Army operational area was Western Rumelia, and it had units in Europe (Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia) and also one in Aydın (Minor Asia).[26] The Third Army also had inspectorate functions for twelve Redif (reserve) divisions:[27] The Fourth Army's new operational area was Caucasia and its many troops were scattered along the frontier to keep an eye on the Russian Empire. It commanded the following active divisions and other units:[28] The Fourth Army also had inspectorate functions for four Redif (reserve) divisions:[25]

1909

In 1909, on the paper, the effective 'peace' strength was estimated at 700,620 of which 583,200 were infantry 55,300 cavalry 54,720 artillery. There were 174 field and 22 mountain batteries. From that total active army (260,000) contained 320 battalions of infantry, 203 squadrons of cavalry and 248 (6 gun) batteries of artillery. The Redif, reserve, (120,000) contained 374 battalions of infantry and 666 supplemental and incomplete battalions and 48 squadrons of cavalry.

1910

The division of the empire into seven army corps districts. These were Istanbul, Edirne, Izmir, Erzincan, Damascus, Bagdad and Sana. Also there were two independent divisions Medina and Tripoli would be supplanted and a number of divisions organized each consisting of three regiments nine battalions and a training battalion.

1911

Disposition of the forces in 1911. 1909 military reformation included the creation of corps level headquarters. First Army was headquartered in Harbiye.[29] The Second Army was headquartered in Salonika. Responsible for the Balkans and operational control over forces in Syria and Palestine. the Second Army had the first of two inspectorates.[30] The Third Army was headquartered in Erzincan. The Fifth Army's headquarters were in Baghdad.[31] The Fifth in Syria, and had an inspectorate.

1912

Disposition of the forces in 1912. First army in European Thrace. Second army in Balkans. Third Army in Caucasus. Fourth Army Mesopotamia. VIII Corps in Syria. XIV Corps in Arabia-Yemen

1913

Disposition of the forces in 1913. The original First army degraded during First Balkan Wars.

1914

Before the Empire entered the war, the four armies divided their forces into corps and divisions such that each division had three infantry regiments and an artillery regiment. The main units were: First Army with fifteen divisions; Second Army with 4 divisions plus an independent infantry division with three infantry regiments and an artillery brigade. The second army headquarters was located in Aleppo Syria commanding two corps made up of two divisions. Third Army with nine divisions, four independent infantry regiments and four independent cavalry regiments (tribal units); and the Fourth Army with four divisions. The Redif system had been done away with, and the plan was to have reserve soldiers fill out active units rather than constitute separate units. In August 1914, of 36 infantry divisions organized, fourteen were established from scratch and were essentially new divisions. In a very short time, eight of these newly recruited divisions went through major redeployment.

By November 1914, the Second Army was moved to Istanbul and commanded the V and VI Corps, each composed of three divisions.[32] The Ottoman concentration plan shifted major forces to European Thrace and established the defense of straits. The First and Second army located in this region. The Third army acquired new supplies for a winter offense. The force in Palestine (VIII Corps) is replaced with the Army in Mesopotamia.

1915

On March 24, 1915 5th Army and September 5, 1915 6th Army established. In February 1915 the defense of Straits was reorganized.[33] The Second Army had responsibility for the south and east coasts. It later provided troops to the reinforce the men fighting on the Gallipoli Peninsula, but otherwise played no further role.

1916

In March 1916, the decision was made to deploy the Second Army to the Caucasus Campaign. The Second Army was made up of veterans of the Gallipoli campaign as well as two new divisions. Due to the poor state of the Ottoman rail network, it took a long period of time to move the forces.

Bibliography

- McDowall, David (2004). A Modern History of the Kurds. I.B. Tauris.

- Nicolle, David (2008). The Ottomans: Empire of Faith. Thalamus Publishing. ISBN 978-1902886114.

- Erickson, Edward (2013). Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137362209.

- Erickson, Edward (2001). Order to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-313-31516-7.

- Erickson, Edward (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912-1913. Westport: Palgrave Macmillan.

Notes

- War minister Enver operated a guerrilla unit as an early assignment in Libya. He knew the inherent strengths and limitations. He used special organization to counter act insurgency and support his regular army.[17]

- Abdülhanúd’s Secret Service (Hafive) and Yildaz Palace Intelligence Service (Yildiz Is-tihbarat Teskilati). They were transferred to the ministry of security in 1909.

- There is a large number of cables, notes, summaries (40,000) from 1913 through 1918, which proves the military rather than a political function[17]

- Bahattin akir, Dr. Nazim, Omer Naji, and Hilmi Bey, were members of the special organization talked at Armenian congress at Erzurum

References

- (Erickson 2001, pp. 1)

-

Grant, Jonathan A. (2007). "Austro-German Hegemony in Eastern Europe". Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780674024427. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

The sultan sought a German Military Mission in the aftermath of the Turkish defeat by Russia. In June 1880 he requested that officers of the German General Staff, infantry, cavalry, and artillery services come to the Ottoman Empire on a three-year contract. In April 1882, officers Colonel Köhler, Captain Kamphoevener, Captain von Hobe, and Captain von Ristow arrived, and the sultan gave them ranks within the Ottoman army.

-

Macfie, Alexander Lyon (1998). "The Great Powers and the Ottoman Empire". The End of the Ottoman Empire, 1908-1923. Turning Points. London: Routledge (published 2014). p. 100. ISBN 9781317888659. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

Already in the 1880s, German military missions, led by General Otto Köhler and Lieutenant-Colonel Baron Colmar von der Goltz, had been dispatched to reform the Ottoman army [...].

- (McDowall 2004, pp. 59)

- (McDowall 2004, pp. 59–60)

- (McDowall 2004, pp. 60)

- (McDowall 2004, pp. 61–62)

- (McDowall 2004, pp. 61)

- (Erickson 2013, pp. 124)

- "THE SHORT HISTORY OF THE GENDARMERIE GENERAL COMMAND". Archived from the original on June 25, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- (Erickson 2013, pp. 125)

- David Nicolle, colour plates by Rafaelle Ruggeri, The Ottoman Army 1914-18, Men-at-Arms 269, Ospray Publishing Ltd., 1994, ISBN 1-85532-412-1, p. 14.

- (Erickson 2013, pp. 179)

- (Erickson 2013, pp. 177)

- (Erickson 2013, pp. 178)

- (Erickson 2013, pp. 112)

- (Erickson 2013, pp. 113)

- Shaw, The Ottoman Empire in World War I, Volume I, 355

- (Erickson 2013, pp. 118)

- (Nicolle 2008, pp. 161)

- (Nicolle 2008, pp. 169)

- The Encyclopædia Britannica, Vol.7, Edited by Hugh Chisholm, (1911), 3; Constantinople, the capital of the Turkish Empire...

- Britannica, Istanbul:When the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, the capital was moved to Ankara, and Constantinople was officially renamed Istanbul in 1930.

- Weapons of the Ottoman Army

- (Erickson 2003, pp. 19)

- (Erickson 2003, pp. 17)

- (Erickson 2003, p. 19)

- (Erickson 2003, p. 17)

- (Erickson 2003, pp. 371–375)

- (Erickson 2003, pp. 375–379)

- (Erickson 2003, pp. 382–383)

- (Erickson 2001, p. 43)

- (Erickson 2001, p. 80)

- (Erickson 2001, p. 180)