Perinatal asphyxia

Perinatal asphyxia (also known as neonatal asphyxia or birth asphyxia) is the medical condition resulting from deprivation of oxygen to a newborn infant that lasts long enough during the birth process to cause physical harm, usually to the brain. It is also the inability to establish and sustain adequate or spontaneous respiration upon delivery of the newborn. It remains a serious condition which causes significant mortality and morbidity. It is an emergency condition and requires adequate and quick resuscitation measures.Perinatal asphyxia is also an oxygen deficit from the 28th week of gestation to the first seven days following delivery. It is also an insult to the fetus or newborn due to lack of oxygen or lack of perfusion to various organs and may be associated with a lack of ventilation. In accordance with WHO, perinatal asphyxia is characterised by- Profound metabolic acidosis, with a PH <7.20 on umbilical cord arterial blood sample, Persistence of an APGAR score of 3 at the 5th minute, Clinical neurologic sequelae in the immediate neonatal period,Evidence of multiorgan system dysfunction in the immediate neonatal period. Hypoxic damage can occur to most of the infant's organs (heart, lungs, liver, gut, kidneys), but brain damage is of most concern and perhaps the least likely to quickly or completely heal. In more pronounced cases, an infant will survive, but with damage to the brain manifested as either mental, such as developmental delay or intellectual disability, or physical, such as spasticity.

| Perinatal asphyxia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Neonatal asphyxia |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, obstetrics |

It results most commonly from antepartum causes like a drop in maternal blood pressure or some other substantial interference with blood flow to the infant's brain during delivery. This can occur due to inadequate circulation or perfusion, impaired respiratory effort, or inadequate ventilation. Perinatal asphyxia happens in 2 to 10 per 1000 newborns that are born at term, and more for those that are born prematurely.[1] WHO estimates that 4 million neonatal deaths occur yearly due to birth asphyxia, representing 38% of deaths of children under 5 years of age.[2]

Perinatal asphyxia can be the cause of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy or intraventricular hemorrhage, especially in preterm births. An infant suffering severe perinatal asphyxia usually has poor color (cyanosis), perfusion, responsiveness, muscle tone, and respiratory effort, as reflected in a low 5 minute Apgar score. Extreme degrees of asphyxia can cause cardiac arrest and death. If resuscitation is successful, the infant is usually transferred to a neonatal intensive care unit.

There has long been a scientific debate over whether newborn infants with asphyxia should be resuscitated with 100% oxygen or normal air.[3] It has been demonstrated that high concentrations of oxygen lead to generation of oxygen free radicals, which have a role in reperfusion injury after asphyxia.[4] Research by Ola Didrik Saugstad and others led to new international guidelines on newborn resuscitation in 2010, recommending the use of normal air instead of 100% oxygen.[5][6]

There is considerable controversy over the diagnosis of birth asphyxia due to medicolegal reasons.[7][8] Because of its lack of precision, the term is eschewed in modern obstetrics.[9]

Cause

Basically, understanding of the etiology of perinatal asphyxia provides the platform on which to build on its pathophysiology. The general principles guiding the causes and the pathophysiology of perinatal asphyxia are grouped into antepartum causes and intra partum causes. As these are the various points to which insults can occur to the foetus.

- Antepartum causes

- Inadequate oxygenation of maternal blood due to hypoventilation during anesthesia, heart diseases, pneumonia, respiratory failure

- Low maternal blood pressure due to hypotension e.g. compression of vena cava and aorta, excess anaesthesia.

- Premature separation of placenta

- Placental insufficiency

- Intra partum causes

- Inadequate relaxation of uterus due to excess oxytocin

- prolonged delivery

- Knotting of umbilical cord around the neck of infant

Risk factors

- Elderly or young mothers

- Prolonged rupture of membranes

- Meconium-stained fluid

- Multiple births

- Lack of antenatal care

- Low birth weight infants

- Malpresentation

- Augmentation of labour with oxytocin

- Antepartum hemorrhage

- Severe eclampsia and pre-eclampsia

- Antepartum and intrapartum anemia[10]

Treatment

- A= Establish open airway: Suctioning, if necessary endotracheal intubation

- B= Breathing: Through tactile stimulation, PPV, bag and mask, or through endotracheal tube

- C= Circulation: Through chest compressions and medications if needed

- D= Drugs: Adrenaline .01 of .1 solution

- Hypothermia treatment to reduce the extent of brain injury

- Epinephrine 1:10000 (0.1-0.3ml/kg) IV

- Saline solution for hypovolemia

Epidemiology

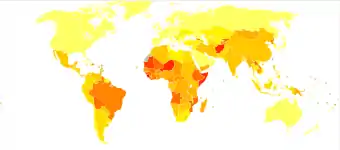

A 2008 bulletin from the World Health Organization estimates that 900,000 total infants die each year from birth asphyxia, making it a leading cause of death for newborns.[11]

In the United States, intrauterine hypoxia and birth asphyxia was listed as the tenth leading cause of neonatal death.[12]

Medicolegal aspects

There is current controversy regarding the medicolegal definitions and impacts of birth asphyxia. Plaintiff's attorneys often take the position that birth asphyxia is often preventable, and is often due to substandard care and human error.[13] They have utilized some studies in their favor that have demonstrated that, "... although other potential causes exist, asphyxia and hypoxic-ihy affect a substantial number of babies, and they are preventable causes of cerebral palsy."[14][15][16] The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists disputes that conditions such as cerebral palsy are usually attributable to preventable causes, instead associating them with circumstances arising prior to birth and delivery.[17]

References

- Truwit, C. L.; Barkovich, A. J. (November 1990). "Brain damage from perinatal asphyxia: correlation of MR findings with gestational age". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 11 (6): 1087–1096. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Aslam, Hafiz Muhammad; Saleem, Shafaq; Afzal, Rafia; Iqbal, Umair; Saleem, Sehrish Muhammad; Shaikh, Muhammad Waqas Abid; Shahid, Nazish (2014-12-20). "Risk factors of birth asphyxia". Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 40: 94. doi:10.1186/s13052-014-0094-2. ISSN 1824-7288. PMC 4300075. PMID 25526846.

- Davis, PG; Tan, A; O'Donnell, CPF; Schulze, A (2004). "Resuscitation of newborn infants with 100% oxygen or air: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. 364 (9442): 1329–1333. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17189-4. PMID 15474135.

- Kutzsche, S; Ilves, P; Kirkeby, OJ; Saugstad, OD (2001). "Hydrogen peroxide production in leukocytes during cerebral hypoxia and reoxygenation with 100% or 21% oxygen in newborn piglets". Pediatric Research. 49 (6): 834–842. doi:10.1203/00006450-200106000-00020. PMID 11385146.

- ILCOR Neonatal Resuscitation Guidelines 2010

- Norwegian paediatrician honoured by University of Athens, Norway.gr

- Blumenthal, I (2001). "Cerebral palsy—medicolegal aspects". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 94 (12): 624–7. doi:10.1177/014107680109401205. PMC 1282294. PMID 11733588.

- Dhar, KK; Ray, SN; Dhall, GI (1995). "Significance of nuchal cord". Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 93 (12): 451–3. PMID 8773129.

- ACOG. "Committee Opinion, Number 326, December 2005: Inappropriate Use of the Terms Fetal Distress and Birth Asphyxia". Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kaye, D. (2003-03-01). "Antenatal and intrapartum risk factors for birth asphyxia among emergency obstetric referrals in Mulago Hospital, Kampala, Uganda". East African Medical Journal. 80 (3): 140–143. doi:10.4314/eamj.v80i3.8683. ISSN 0012-835X. PMID 12762429.

- Spector J, Daga S. "Preventing those so-called stillbirths". WHO. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- National Center for Health Statistics

- Andreasen, Stine (2014). "Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 93 (2): 152–158. doi:10.1111/aogs.12276. PMID 24237480.

- "APFEL Handout: Birth Asphyxia & Cerebral Palsy" (PDF). Colorado Bar Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- Cohen, Frances M. (2003). "Origin and Timing of Brain Lesions in Term Infants with Neonatal Encephalopathy". The Lancet. 361 (9359): 736–42. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12658-X. PMID 12620738.

- Becher, J-C; Stenson, Bj; Lyon, Aj (2007-11-01). "Is intrapartum asphyxia preventable?". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 114 (11): 1442–1444. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01487.x. ISSN 1471-0528. PMID 17877776.

- Van Eerden, Peter. "Summary of the Publication, "Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy: Defining the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology," by the ACOG Task Force on Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy". Medscape. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |