Cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest is a sudden loss of blood flow resulting from the failure of the heart to pump effectively.[11] Signs include loss of consciousness and abnormal or absent breathing.[1][2] Some individuals may experience chest pain, shortness of breath, or nausea before cardiac arrest.[2] If not treated within minutes, it typically leads to death.[11]

| Cardiac arrest | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cardiopulmonary arrest, circulatory arrest, sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), sudden cardiac death (SCD)[1] |

| |

| CPR being administered during a simulation of cardiac arrest. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Loss of consciousness, abnormal or no breathing[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Older age[3] |

| Causes | Coronary artery disease, congenital heart defect, major blood loss, lack of oxygen, very low potassium, heart failure[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Finding no pulse[1] |

| Prevention | Not smoking, physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, healthy eating[5] |

| Treatment | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), defibrillation[6] |

| Prognosis | Survival rate ~ 10% (outside of hospital) 25% (in hospital)[7][8] |

| Frequency | 13 per 10,000 people per year (outside hospital in the US)[9] |

| Deaths | > 425,000 per year (U.S.)[10] |

The most common cause of cardiac arrest is coronary artery disease.[4] Less common causes include major blood loss, lack of oxygen, very low potassium, heart failure, and intense physical exercise.[4] A number of inherited disorders may also increase the risk including long QT syndrome.[4] The initial heart rhythm is most often ventricular fibrillation.[4] The diagnosis is confirmed by finding no pulse.[1] While a cardiac arrest may be caused by heart attack or heart failure, these are not the same.[11]

Prevention includes not smoking, physical activity, and maintaining a healthy weight.[5] Treatment for cardiac arrest includes immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and, if a shockable rhythm is present, defibrillation.[6] Among those who survive, targeted temperature management may improve outcomes.[12][13] An implantable cardiac defibrillator may be placed to reduce the chance of death from recurrence.[5]

In the United States, approximately 535,000 cases occur a year.[9] About 13 per 10,000 people (326,000 or 61%) experience cardiac arrest outside of a hospital setting, while 209,000 (39%) occur within a hospital.[9] Cardiac arrest becomes more common with age.[3] It affects males more often than females.[3] The percentage of people who survive out of hospital cardiac arrest with treatment by emergency medical services is about 8%.[7] Many who survive have significant disability.[7] However, many American television programs have portrayed unrealistically high survival rates of 67%.[7]

Signs and symptoms

Cardiac arrest is not preceded by any warning symptoms in approximately 50 percent of people.[14] For those who do experience symptoms, they will be non-specific, such as new or worsening chest pain, fatigue, blackouts, dizziness, shortness of breath, weakness and vomiting.[15][16] When cardiac arrest occurs, the most obvious sign of its occurrence will be the lack of a palpable pulse in the victim. Also, as a result of loss of cerebral perfusion (blood flow to the brain), the victim will rapidly lose consciousness and will stop breathing. The main criterion for diagnosing a cardiac arrest, as opposed to respiratory arrest, which shares many of the same features, is lack of circulation; however, there are a number of ways of determining this. Near-death experiences are reported by 10 to 20 percent of people who survived cardiac arrest.[17]

Certain types of prompt intervention can often reverse a cardiac arrest, but without such intervention, death is all but certain.[18] In certain cases, cardiac arrest is an anticipated outcome of a serious illness where death is expected.[19]

Causes

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) and sudden cardiac death (SCD) occur when the heart abruptly begins to beat in an abnormal or irregular rhythm (arrhythmia).[20] Without organized electrical activity in the heart muscle, there is no consistent contraction of the ventricles, which results in the heart's inability to generate an adequate cardiac output (forward pumping of blood from heart to rest of the body).[21] There are many different types of arrhythmias, but the ones most frequently recorded in SCA and SCD are ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF).[22] Less common causes of dysrhythmias in cardiac arrest include pulseless electrical activity (PEA) or asystole.[20] Such rhythms are seen when there is prolonged cardiac arrest, progression of ventricular fibrillation, or due to efforts such as defibrillation to resuscitate the person.[20]

Sudden cardiac arrest can result from cardiac and non-cardiac causes including the following:

Coronary artery disease

Coronary artery disease (CAD), also known as ischemic heart disease, is responsible for 62 to 70 percent of all SCDs.[23][24] CAD is a much less frequent cause of SCD in people under the age of 40.[23]

Cases have shown that the most common finding at postmortem examination of sudden cardiac death (SCD) is chronic high-grade stenosis of at least one segment of a major coronary artery, the arteries that supply the heart muscle with its blood supply.[25]

Structural heart disease

Structural heart diseases not related to CAD account for 10% of all SCDs.[21][24] Examples of these include: cardiomyopathies (hypertrophic, dilated, or arrythmogenic), cardiac rhythm disturbances, congenital coronary artery anomalies, myocarditis, hypertensive heart disease,[26] and congestive heart failure.[27]

Left ventricular hypertrophy is thought to be a leading cause of SCD in the adult population.[28][20] This is most commonly the result of longstanding high blood pressure which has caused secondary damage to the wall of the main pumping chamber of the heart, the left ventricle.[29]

A 1999 review of SCDs in the United States found that this accounted for over 30% of SCDs for those under 30 years. A study of military recruits age 18-35 found that this accounted for over 40% of SCDs.[23][24]

Congestive heart failure increases the risk of SCD fivefold.[27]

Inherited arrhythmia syndromes

Arrhythmias that are not due to structural heart disease account for 5 to 10% of sudden cardiac arrests.[30][31][32] These are frequently caused by genetic disorders that lead to abnormal heart rhythms.[20] The genetic mutations often affect specialised proteins known as ion channels that conduct electrically charged particles across the cell membrane, and this group of conditions are therefore often referred to as channelopathies. Examples of these inherited arrhythmia syndromes include Long QT syndrome, Brugada Syndrome, Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and Short QT syndrome. Other conditions that promote arrhythmias but are not caused by genetic mutations include Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.[21]

Long QT syndrome, a condition often mentioned in young people's deaths, occurs in one of every 5000 to 7000 newborns and is estimated to be responsible for 3000 deaths each year compared to the approximately 300,000 cardiac arrests seen by emergency services.[33] These conditions are a fraction of the overall deaths related to cardiac arrest but represent conditions which may be detected prior to arrest and may be treatable.

Non-cardiac causes

SCA due to non-cardiac causes accounts for the remaining 15 to 25%.[32][34] The most common non-cardiac causes are trauma, major bleeding (gastrointestinal bleeding, aortic rupture, or intracranial hemorrhage), hypovolemic shock, overdose, drowning, and pulmonary embolism.[34][35][36] Cardiac arrest can also be caused by poisoning (for example, by the stings of certain jellyfish), or through electrocution, lightning.[20]

Mnemonic for reversible causes

"Hs and Ts" is the name for a mnemonic used to aid in remembering the possible treatable or reversible causes of cardiac arrest.[37][38][39]

- Hs

- Hypovolemia – A lack of blood volume

- Hypoxia – A lack of oxygen

- Hydrogen ions (Acidosis) – An abnormal pH in the body

- Hyperkalemia or Hypokalemia – Both increased or decreased potassium can be life-threatening.

- Hypothermia – A low core body temperature

- Hypoglycemia or Hyperglycemia – Low or high blood glucose

- Ts

- Tablets or Toxins such as drug overdose

- Cardiac Tamponade – Fluid building up around the heart

- Tension pneumothorax – A collapsed lung

- Thrombosis (Myocardial infarction) – Heart attack

- Thromboembolism (Pulmonary embolism) – A blood clot in the lung

- Traumatic cardiac arrest

Children

In children, the most common cause of cardiopulmonary arrest is shock or respiratory failure that has not been treated, rather than a heart arrhythmia.[20] When there is a cardiac arrhythmia, it is most often asystole or bradycardia, in contrast to ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia as seen in adults.[20] Other causes can include drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, or overdose of medications such as antidepressants in a child who was previously healthy but is now presenting with a dysrhythmia that has progressed to cardiac arrest.[20]

Risk factors

The risk factors for SCD are similar to those of coronary artery disease and include age, cigarette smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, lack of physical exercise, obesity, diabetes, and family history.[40] A prior episode of sudden cardiac arrest also increases the risk of future episodes.[41]

Air pollution is also associated with the risk of cardiac arrest.[42] Current cigarette smokers with coronary artery disease were found to have a two to threefold increase in the risk of sudden death between ages 30 and 59. Furthermore, it was found that former smokers’ risk was closer to that of those who had never smoked.[14][43]

Mechanism

The mechanism responsible for the majority of sudden cardiac deaths is ventricular fibrillation.[4] Structural changes in the diseased heart as a result of inherited factors (mutations in ion-channel coding genes for example) cannot explain the suddenness of SCD.[44] Also, sudden cardiac death could be the consequence of electric-mechanical disjunction and bradyarrhythmias.[45][46]

Diagnosis

Cardiac arrest is synonymous with clinical death.[47] Historical information and a physical exam diagnosis cardiac arrest, as well as provides information regarding the potential cause and the prognosis.[20] The history should aim to determine if the episode was observed by anyone else, what time the episode took place, what the person was doing (in particular if there was any trauma), and involvement of drugs.[20]

The physical examination portion of diagnosis cardiac arrest focuses on the absence of a pulse clinically.[20] In many cases lack of carotid pulse is the gold standard for diagnosing cardiac arrest, as lack of a pulse (particularly in the peripheral pulses) may result from other conditions (e.g. shock), or simply an error on the part of the rescuer.[48] Nonetheless, studies have shown that rescuers often make a mistake when checking the carotid pulse in an emergency, whether they are healthcare professionals[48] or lay persons.[49]

Owing to the inaccuracy in this method of diagnosis, some bodies such as the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) have de-emphasised its importance. The Resuscitation Council (UK), in line with the ERC's recommendations and those of the American Heart Association,[47] have suggested that the technique should be used only by healthcare professionals with specific training and expertise, and even then that it should be viewed in conjunction with other indicators such as agonal respiration.[50]

Various other methods for detecting circulation have been proposed. Guidelines following the 2000 International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) recommendations were for rescuers to look for "signs of circulation", but not specifically the pulse.[47] These signs included coughing, gasping, colour, twitching, and movement.[51] However, in face of evidence that these guidelines were ineffective, the current recommendation of ILCOR is that cardiac arrest should be diagnosed in all casualties who are unconscious and not breathing normally.[47] Another method is to use molecular autopsy or postmortem molecular testing which uses a set of molecular techniques to find the ion channels that are cardiac defective.[52]

Other physical findings can help determine the potential cause of the cardiac arrest.[20]

| Location | Findings | Possible Causes |

|---|---|---|

| General | Pale skin | Hemorrhage |

| Decreased body temperature | Hypothermia | |

| Airway | Presence of secretions, vomit, blood | Aspiration |

| Inability to provide positive pressure ventilation | Tension pneumothorax | |

| Neck | Distension of the neck veins | Tension pneumothorax |

| Trachea shifted to one side | Tension pneumothorax | |

| Chest | Scar in the middle of the sternum | Cardiac disease |

| Lungs | Breath sounds only on one side | Tension pneumothorax

Aspiration |

| No breath sounds or distant breath sounds | Esophageal intubation

Airway obstruction | |

| Wheezing | Aspiration | |

| Rales | Aspiration

Pulmonary edema Pneumonia | |

| Heart | Decreased heart sounds | Hypovolemia

Cardiac tamponade Tension pneumothorax Pulmonary embolus |

| Abdomen | Distended and dull | Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy |

| Distended and tympanic | Esophageal intubation | |

| Rectal | Blood present | Gastrointestinal hemorrhage |

| Extremities | Asymmetrical pulses | Aortic dissection |

| Skin | Needle tracks | Drug abuse |

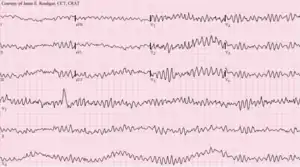

Classifications

Clinicians classify cardiac arrest into "shockable" versus "non-shockable", as determined by the ECG rhythm. This refers to whether a particular class of cardiac dysrhythmia is treatable using defibrillation.[50] The two "shockable" rhythms are ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia while the two "non-shockable" rhythms are asystole and pulseless electrical activity.[53]

Prevention

With positive outcomes following cardiac arrest unlikely, an effort has been spent in finding effective strategies to prevent cardiac arrest. With the prime causes of cardiac arrest being ischemic heart disease, efforts to promote a healthy diet, exercise, and smoking cessation are important. For people at risk of heart disease, measures such as blood pressure control, cholesterol lowering, and other medico-therapeutic interventions are used. A Cochrane review published in 2016 found moderate-quality evidence to show that blood pressure-lowering drugs do not appear to reduce sudden cardiac death.[54]

Code teams

In medical parlance, cardiac arrest is referred to as a "code" or a "crash". This typically refers to "code blue" on the hospital emergency codes. A dramatic drop in vital sign measurements is referred to as "coding" or "crashing", though coding is usually used when it results in cardiac arrest, while crashing might not. Treatment for cardiac arrest is sometimes referred to as "calling a code".

People in general wards often deteriorate for several hours or even days before a cardiac arrest occurs.[50][55] This has been attributed to a lack of knowledge and skill amongst ward-based staff, in particular, a failure to carry out measurement of the respiratory rate, which is often the major predictor of a deterioration[50] and can often change up to 48 hours prior to a cardiac arrest. In response to this, many hospitals now have increased training for ward-based staff. A number of "early warning" systems also exist which aim to quantify the person's risk of deterioration based on their vital signs and thus provide a guide to staff. In addition, specialist staff are being used more effectively in order to augment the work already being done at ward level. These include:

- Crash teams (or code teams) – These are designated staff members with particular expertise in resuscitation who are called to the scene of all arrests within the hospital. This usually involves a specialized cart of equipment (including defibrillator) and drugs called a "crash cart" or "crash trolley".

- Medical emergency teams – These teams respond to all emergencies, with the aim of treating the people in the acute phase of their illness in order to prevent a cardiac arrest. These teams have been found to decrease the rates of in-hospital cardiac arrest and improve survival.[9]

- Critical care outreach – As well as providing the services of the other two types of team, these teams are also responsible for educating non-specialist staff. In addition, they help to facilitate transfers between intensive care/high dependency units and the general hospital wards. This is particularly important, as many studies have shown that a significant percentage of patients discharged from critical care environments quickly deteriorate and are re-admitted; the outreach team offers support to ward staff to prevent this from happening.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator

An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) is a battery-powered device that monitors electrical activity in the heart and when an arrhythmia or asystole is detected is able to deliver an electrical shock to terminate the abnormal rhythm. ICDs are used to prevent sudden cardiac death (SCD) in those that have survived a prior episode of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) due to ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia (secondary prevention).[56] ICD's are also used prophylactically to prevent sudden cardiac death in certain high risk patient populations (primary prevention).[57]

Numerous studies have been conducted on the use of ICDs for the secondary prevention of SCD. These studies have shown improved survival with ICD's compared to the use of anti-arrhythmic drugs.[56] ICD therapy is associated with a 50% relative risk reduction in death caused by an arrhythmia and a 25% relative risk reduction in all cause mortality.[58]

Primary prevention of SCD with ICD therapy for high-risk patient populations has similarly shown improved survival rates in a number of large studies. The high-risk patient populations in these studies were defined as those with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy (determined by a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)). The LVEF criteria used in these trials ranged from less than or equal to 30% in MADIT-II to less than or equal to 40% in MUSTT.[56][57]

Diet

Marine-derived omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) have been promoted for the prevention of sudden cardiac death due to their postulated ability to lower triglyceride levels, prevent arrhythmias, decrease platelet aggregation, and lower blood pressure.[59] However, according to a recent systematic review, omega-3 PUFA supplementation are not being associated with a lower risk of sudden cardiac death.[60]

Management

Sudden cardiac arrest may be treated via attempts at resuscitation. This is usually carried out based upon basic life support, advanced cardiac life support (ACLS), pediatric advanced life support (PALS), or neonatal resuscitation program (NRP) guidelines.[47][61]

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is essential to surviving cardiac arrest with good neurological function.[62][20] It is recommended that it be started as soon as possible with minimal interruptions once begun. The components of CPR that make the greatest difference in survival are chest compressions and defibrillating shockable rhythms.[39] After defibrillation, chest compressions should be continued for two minutes before a rhythm check is again done.[20] This is based on a compression rate of 100-120 compressions per minute, a compression depth of 5–6 centimeters into the chest, full chest recoil, and a ventilation rate of 10 breath ventilations per minute.[20] Correctly performed bystander CPR has been shown to increase survival; however, it is performed in less than 30% of out of hospital arrests as of 2007.[63] If high-quality CPR has not resulted in return of spontaneous circulation and the person's heart rhythm is in asystole, discontinuing CPR and pronouncing the person's death is reasonable after 20 minutes.[64] Exceptions to this include certain cases with hypothermia or who have drowned.[39][64] Some of these cases should have longer and more sustained CPR until they are nearly normothermic.[39] Longer durations of CPR may be reasonable in those who have cardiac arrest while in hospital.[65] Bystander CPR, by the lay public, before the arrival of EMS also improves outcomes.[9]

Either a bag valve mask or an advanced airway may be used to help with breathing particularly since vomiting and regurgitation are common, particularly in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA).[66][67][68] If this occurs, then modification to existing oropharyngeal suction may be required, such as the use of Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy Airway Decontamination.[69] High levels of oxygen are generally given during CPR.[66] Tracheal intubation has not been found to improve survival rates or neurological outcome in cardiac arrest[63][70] and in the prehospital environment may worsen it.[71] Endotracheal tube and supraglottic airways appear equally useful.[70] When done by EMS 30 compressions followed by two breaths appear better than continuous chest compressions and breaths being given while compressions are ongoing.[72]

For bystanders, CPR which involves only chest compressions results in better outcomes as compared to standard CPR for those who have gone into cardiac arrest due to heart issues.[72] Mechanical chest compressions (as performed by a machine) are no better than chest compressions performed by hand.[66] It is unclear if a few minutes of CPR before defibrillation results in different outcomes than immediate defibrillation.[73] If cardiac arrest occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy someone should pull or push the uterus to the left during CPR.[74] If a pulse has not returned by four minutes emergency Cesarean section is recommended.[74]

Defibrillation

Defibrillation is indicated if a shockable rhythm is present. The two shockable rhythms are ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia. In children 2 to 4 J/Kg is recommended.[75]

In addition, there is increasing use of public access defibrillation. This involves placing an automated external defibrillator in public places, and training staff in these areas how to use them. This allows defibrillation to take place prior to the arrival of emergency services and has been shown to lead to increased chances of survival. Some defibrillators even provide feedback on the quality of CPR compressions, encouraging the lay rescuer to press the person's chest hard enough to circulate blood.[76] In addition, it has been shown that those who have arrests in remote locations have worse outcomes following cardiac arrest.[77]

Medications

As of 2016, medications other than epinephrine (adrenaline), while included in guidelines, have not been shown to improve survival to hospital discharge following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.[39] This includes the use of atropine, lidocaine, and amiodarone.[78][79][80][81][82][39] Epinephrine in adults, as of 2019, appears to improve survival but does not appear to improve neurologically normal survival.[83][84][85] It is generally recommended every five minutes.[66] Vasopressin overall does not improve or worsen outcomes compared to epinephrine.[66] The combination of epinephrine, vasopressin, and methylprednisolone appears to improve outcomes.[86] Some of the lack of long-term benefit may be related to delays in epinephrine use.[87] While evidence does not support its use in children, guidelines state its use is reasonable.[75][39] Lidocaine and amiodarone are also deemed reasonable in children with cardiac arrest who have a shockable rhythm.[66][75] The general use of sodium bicarbonate or calcium is not recommended.[66][88] The use of calcium in children has been associated with poor neurological function as well as decreased survival.[20] Correct dosing of medications in children is dependent on weight.[20] To minimize time spent calculating medication doses, the use of a Broselow tape is recommended.[20]

The 2010 guidelines from the American Heart Association no longer contain the recommendation for using atropine in pulseless electrical activity and asystole for want of evidence for its use.[89][39] Neither lidocaine nor amiodarone, in those who continue in ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation despite defibrillation, improves survival to hospital discharge but both equally improve survival to hospital admission.[90]

Thrombolytics when used generally may cause harm but may be of benefit in those with a confirmed pulmonary embolism as the cause of arrest.[91][74] Evidence for use of naloxone in those with cardiac arrest due to opioids is unclear but it may still be used.[74] In those with cardiac arrest due to local anesthetic, lipid emulsion may be used.[74]

Targeted temperature management

Cooling adults after cardiac arrest who have a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) but no return of consciousness improves outcomes.[12][13] This procedure is called targeted temperature management (previously known as therapeutic hypothermia). People are typically cooled for a 24-hour period, with a target temperature of 32–36 °C (90–97 °F).[92] There are a number of methods used to lower the body temperature, such as applying ice packs or cold-water circulating pads directly to the body, or infusing cold saline. This is followed by gradual rewarming over the next 12 to 24 hrs.[93]

Recent meta-analysis found that the use of therapeutic hypothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is associated with improved survival rates and better neurological outcomes.[12]

Do not resuscitate

Some people choose to avoid aggressive measures at the end of life. A do not resuscitate order (DNR) in the form of an advance health care directive makes it clear that in the event of cardiac arrest, the person does not wish to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation.[94] Other directives may be made to stipulate the desire for intubation in the event of respiratory failure or, if comfort measures are all that are desired, by stipulating that healthcare providers should "allow natural death".[95]

Chain of survival

Several organizations promote the idea of a chain of survival. The chain consists of the following "links":

- Early recognition If possible, recognition of illness before the person develops a cardiac arrest will allow the rescuer to prevent its occurrence. Early recognition that a cardiac arrest has occurred is key to survival for every minute a patient stays in cardiac arrest, their chances of survival drop by roughly 10%.[50]

- Early CPR improves the flow of blood and of oxygen to vital organs, an essential component of treating a cardiac arrest. In particular, by keeping the brain supplied with oxygenated blood, chances of neurological damage are decreased.

- Early defibrillation is effective for the management of ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia[50]

- Early advanced care

- Early post-resuscitation care which may include percutaneous coronary intervention[96]

If one or more links in the chain are missing or delayed, then the chances of survival drop significantly.

These protocols are often initiated by a code blue, which usually denotes impending or acute onset of cardiac arrest or respiratory failure, although in practice, code blue is often called in less life-threatening situations that require immediate attention from a physician.

Other

Resuscitation with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation devices has been attempted with better results for in-hospital cardiac arrest (29% survival) than out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (4% survival) in populations selected to benefit most.[97] Cardiac catheterization in those who have survived an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest appears to improve outcomes although high quality evidence is lacking.[98] It is recommended that it is done as soon as possible in those who have had a cardiac arrest with ST elevation due to underlying heart problems.[66]

The precordial thump may be considered in those with witnessed, monitored, unstable ventricular tachycardia (including pulseless VT) if a defibrillator is not immediately ready for use, but it should not delay CPR and shock delivery or be used in those with unwitnessed out of hospital arrest.[99]

Prognosis

The overall chance of survival among those who have cardiac arrest outside hospital is poor, at 10%.[100][101] Among those who have an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, 70% occur at home and their survival rate is 6%.[102][103] For those who have an in-hospital cardiac arrest, the survival rate is estimated to be 24%.[104] Among children rates of survival are 3 to 16% in North America.[105] For in hospital cardiac arrest survival to discharge is around 22%.[106][39] However, some may have neurological injury that can range from mild memory problems to coma.[39]

Prognosis is typically assessed 72 hours or more after cardiac arrest.[107] Rates of survival are better in those who someone saw collapse, got bystander CPR, or had either ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation when assessed.[108] Survival among those with Vfib or Vtach is 15 to 23%.[108] Women are more likely to survive cardiac arrest and leave hospital than men.[109]

A 1997 review found rates of survival to discharge of 14% although different studies varied from 0 to 28%.[110] In those over the age of 70 who have a cardiac arrest while in hospital, survival to hospital discharge is less than 20%.[111] How well these individuals are able to manage after leaving hospital is not clear.[111]

A study of survival rates from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest found that 14.6% of those who had received resuscitation by paramedics survived as far as admission to hospital. Of these, 59% died during admission, half of these within the first 24 hours, while 46% survived until discharge from hospital. This reflects an overall survival following cardiac arrest of 6.8%. Of these 89% had normal brain function or mild neurological disability, 8.5% had moderate impairment, and 2% had major neurological disability. Of those who were discharged from hospital, 70% were still alive four years later.[112]

Epidemiology

Based on death certificates, sudden cardiac death accounts for about 15% of all deaths in Western countries.[113] In the United States 326,000 cases of out of hospital and 209,000 cases of in hospital cardiac arrest occur among adults a year.[9][39] The lifetime risk is three times greater in men (12.3%) than women (4.2%) based on analysis of the Framingham Heart Study.[114] However this gender difference disappeared beyond 85 years of age.[113] Around half of these individuals are younger than 65 years of age.[39]

In the United States during pregnancy cardiac arrest occurs in about one in twelve thousand deliveries or 1.8 per 10,000 live births.[74] Rates are lower in Canada.[74]

Society and culture

Names

In many publications the stated or implicit meaning of "sudden cardiac death" is sudden death from cardiac causes.[115] However, sometimes physicians call cardiac arrest "sudden cardiac death" even if the person survives. Thus one can hear mentions of "prior episodes of sudden cardiac death" in a living person.[116]

In 2006 the American Heart Association presented the following definitions of sudden cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death: "Cardiac arrest is the sudden cessation of cardiac activity so that the victim becomes unresponsive, with no normal breathing and no signs of circulation. If corrective measures are not taken rapidly, this condition progresses to sudden death. Cardiac arrest should be used to signify an event as described above, that is reversed, usually by CPR and/or defibrillation or cardioversion, or cardiac pacing. Sudden cardiac death should not be used to describe events that are not fatal".[117]

Slow code

In some medical facilities, the resuscitation team may purposely respond slowly to a person in cardiac arrest, a practice known as "slow code", or may fake the response altogether for the sake of the person's family, a practice known as "show code".[118] This is generally done for people for whom performing CPR will have no medical benefit.[119] Such practices are ethically controversial,[120] and are banned in some jurisdictions.

References

- Field JM (2009). The Textbook of Emergency Cardiovascular Care and CPR. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 11. ISBN 9780781788991. Archived from the original on 2017-09-05.

- "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "Who Is at Risk for Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "What Causes Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "How Can Death Due to Sudden Cardiac Arrest Be Prevented?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "How Is Sudden Cardiac Arrest Treated?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- Adams JG (2012). Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials (Expert Consult – Online). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1771. ISBN 978-1455733941. Archived from the original on 2017-09-05.

- Andersen, LW; Holmberg, MJ; Berg, KM; Donnino, MW; Granfeldt, A (26 March 2019). "In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Review". JAMA. 321 (12): 1200–1210. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.1696. PMC 6482460. PMID 30912843.

- Kronick SL, Kurz MC, Lin S, Edelson DP, Berg RA, Billi JE, Cabanas JG, Cone DC, Diercks DB, Foster JJ, Meeks RA, Travers AH, Welsford M (November 2015). "Part 4: Systems of Care and Continuous Quality Improvement: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S397-413. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000258. PMID 26472992. S2CID 10073267.

- Meaney, PA; Bobrow, BJ; Mancini, ME; Christenson, J; de Caen, AR; Bhanji, F; Abella, BS; Kleinman, ME; Edelson, DP; Berg, RA; Aufderheide, TP; Menon, V; Leary, M; CPR Quality Summit Investigators, the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee, and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and, Resuscitation. (23 July 2013). "Cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: [corrected] improving cardiac resuscitation outcomes both inside and outside the hospital: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association". Circulation. 128 (4): 417–35. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829d8654. PMID 23801105.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "What Is Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". NHLBI. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- Schenone AL, Cohen A, Patarroyo G, Harper L, Wang X, Shishehbor MH, Menon V, Duggal A (November 2016). "Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: A systematic review/meta-analysis exploring the impact of expanded criteria and targeted temperature". Resuscitation. 108: 102–110. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.07.238. PMID 27521472.

- Arrich J, Holzer M, Havel C, Müllner M, Herkner H (February 2016). "Hypothermia for neuroprotection in adults after cardiopulmonary resuscitation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD004128. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004128.pub4. PMC 6516972. PMID 26878327.

- Myerburg RJ, ed. (2015). "Cardiac Arrest and Sudden Cardiac Death". Braunwald's heart disease : a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Mann, Douglas L.; Zipes, Douglas P.; Libby, Peter; Bonow, Robert O.; Braunwald, Eugene (Tenth ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. pp. 821–860. ISBN 9781455751341. OCLC 890409638.

- "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Sudden Cardiac Arrest?". National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. 1 April 2011. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- Johnson, Ken; Ghassemzadeh, Sassan (2019), "Chest Pain", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262011, retrieved 2019-11-05

- Parnia S, Spearpoint K, Fenwick PB (August 2007). "Near death experiences, cognitive function and psychological outcomes of surviving cardiac arrest". Resuscitation. 74 (2): 215–21. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.01.020. PMID 17416449.

- Jameson JL, Kasper DL, Harrison TR, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL (2005). Harrison's principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. ISBN 978-0-07-140235-4.

- "Mount Sinai – Cardiac arrest". Archived from the original on 2012-05-15.

- Walls, Ron M., editor. Hockberger, Robert S., editor. Gausche-Hill, Marianne, editor. (2017-03-09). Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice. ISBN 9780323390163. OCLC 989157341.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Podrid PJ (2016-08-22). "Pathophysiology and etiology of sudden cardiac arrest". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer M, Gregoratos G, Klein G, Moss AJ, Myerburg RJ, Priori SG, Quinones MA, Roden DM, Silka MJ, Tracy C, Smith SC, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Antman EM, Anderson JL, Hunt SA, Halperin JL, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Dean V, Deckers JW, Despres C, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Tamargo JL, Zamorano JL (September 2006). "ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 114 (10): e385-484. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178233. PMID 16935995.

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (February 2002). "State-specific mortality from sudden cardiac death—United States, 1999". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 51 (6): 123–6. PMID 11898927.

- Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA (October 2001). "Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998". Circulation. 104 (18): 2158–63. doi:10.1161/hc4301.098254. PMID 11684624.

- Fuster V, Topol EJ, Nabel EG (2005). Atherothrombosis and Coronary Artery Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781735834. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03.

- Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA (October 2001). "Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998". Circulation. 104 (18): 2158–63. doi:10.1161/hc4301.098254. PMID 11684624.

- Kannel WB, Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Cobb J (August 1998). "Sudden coronary death in women". American Heart Journal. 136 (2): 205–12. doi:10.1053/hj.1998.v136.90226. PMID 9704680.

- Stevens SM, Reinier K, Chugh SS (February 2013). "Increased left ventricular mass as a predictor of sudden cardiac death: is it time to put it to the test?". Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 6 (1): 212–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.112.974931. PMC 3596001. PMID 23424223.

- Katholi RE, Couri DM (2011). "Left ventricular hypertrophy: major risk factor in patients with hypertension: update and practical clinical applications". International Journal of Hypertension. 2011: 495349. doi:10.4061/2011/495349. PMC 3132610. PMID 21755036.

- Chugh SS, Kelly KL, Titus JL (August 2000). "Sudden cardiac death with apparently normal heart". Circulation. 102 (6): 649–54. doi:10.1161/01.cir.102.6.649. PMID 10931805.

- "Survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with apparently normal heart. Need for definition and standardized clinical evaluation. Consensus Statement of the Joint Steering Committees of the Unexplained Cardiac Arrest Registry of Europe and of the Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation Registry of the United States". Circulation. 95 (1): 265–72. January 1997. doi:10.1161/01.cir.95.1.265. PMID 8994445.

- Drory Y, Turetz Y, Hiss Y, Lev B, Fisman EZ, Pines A, Kramer MR (November 1991). "Sudden unexpected death in persons less than 40 years of age". The American Journal of Cardiology. 68 (13): 1388–92. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(91)90251-f. PMID 1951130.

- Sudden Cardiac Death Archived 2010-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Kuisma M, Alaspää A (July 1997). "Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests of non-cardiac origin. Epidemiology and outcome". European Heart Journal. 18 (7): 1122–8. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015407. PMID 9243146.

- Raab, Helmut; Lindner, Karl H.; Wenzel, Volker (2008). "Preventing cardiac arrest during hemorrhagic shock with vasopressin". Critical Care Medicine. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health). 36 (Suppl): S474–S480. doi:10.1097/ccm.0b013e31818a8d7e. ISSN 0090-3493. PMID 20449913.

- Voelckel, Wolfgang G.; Lurie, Keith G.; Lindner, Karl H.; Zielinski, Todd; McKnite, Scott; Krismer, Anette C.; Wenzel, Volker (2000). "Vasopressin Improves Survival After Cardiac Arrest in Hypovolemic Shock". Anesthesia & Analgesia. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health). 91 (3): 627–634. doi:10.1097/00000539-200009000-00024. ISSN 0003-2999. PMID 10960389.

- "Resuscitation Council (UK) Guidelines 2005". Archived from the original on 2009-12-15.

- Ecc Committee, Subcommittees Task Forces of the American Heart Association (December 2005). "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 112 (24 Suppl): IV1-203. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. PMID 16314375.

- Cydulka, Rita K., editor. (2017-08-28). Tintinalli's emergency medicine manual. ISBN 9780071837026. OCLC 957505642.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Friedlander Y, Siscovick DS, Weinmann S, Austin MA, Psaty BM, Lemaitre RN, Arbogast P, Raghunathan TE, Cobb LA (January 1998). "Family history as a risk factor for primary cardiac arrest". Circulation. 97 (2): 155–60. doi:10.1161/01.cir.97.2.155. PMID 9445167.

- Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J (2014). "327. Cardiovascular Collapse, Cardiac Arrest, and Sudden Cardiac Death". Harrison's principles of internal medicine (19th ed.). New York. ISBN 9780071802154. OCLC 893557976.

- Teng TH, Williams TA, Bremner A, Tohira H, Franklin P, Tonkin A, Jacobs I, Finn J (January 2014). "A systematic review of air pollution and incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 68 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-203116. hdl:20.500.11937/11721. PMID 24101168. S2CID 26111030.

- Goldenberg I, Jonas M, Tenenbaum A, Boyko V, Matetzky S, Shotan A, Behar S, Reicher-Reiss H (October 2003). "Current smoking, smoking cessation, and the risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with coronary artery disease". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (19): 2301–5. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.19.2301. PMID 14581249.

- Rubart M, Zipes DP (September 2005). "Mechanisms of sudden cardiac death". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 115 (9): 2305–15. doi:10.1172/JCI26381. PMC 1193893. PMID 16138184.

- Bunch TJ, Hohnloser SH, Gersh BJ (May 2007). "Mechanisms of sudden cardiac death in myocardial infarction survivors: insights from the randomized trials of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators". Circulation. 115 (18): 2451–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683235. PMID 17485594.

- "Types of Arrhythmia". National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. 1 April 2011. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- Ecc Committee, Subcommittees Task Forces of the American Heart Association (December 2005). "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 112 (24 Suppl): IV1-203. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. PMID 16314375.

- Ochoa FJ, Ramalle-Gómara E, Carpintero JM, García A, Saralegui I (June 1998). "Competence of health professionals to check the carotid pulse". Resuscitation. 37 (3): 173–5. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(98)00055-0. PMID 9715777.

- Bahr J, Klingler H, Panzer W, Rode H, Kettler D (August 1997). "Skills of lay people in checking the carotid pulse". Resuscitation. 35 (1): 23–6. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(96)01092-1. PMID 9259056.

- "Resuscitation Council (UK) Guidelines 2005". Archived from the original on 2009-12-15.

- British Red Cross; St Andrew's Ambulance Association; St John Ambulance (2006). First Aid Manual: The Authorised Manual of St. John Ambulance, St. Andrew's Ambulance Association, and the British Red Cross. Dorling Kindersley Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4053-1573-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Glatter, Kathryn A.; Chiamvimonvat, Nipavan; He, Yuxia; Chevalier, Philippe; Turillazzi, Emanuela (2006), Rutty, Guy N. (ed.), "Postmortem Analysis for Inherited Ion Channelopathies", Essentials of Autopsy Practice: Current Methods and Modern Trends, Springer, pp. 15–37, doi:10.1007/1-84628-026-5_2, ISBN 978-1-84628-026-9

- Soar J, Perkins JD, Nolan J, eds. (2012). ABC of resuscitation (6th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 43. ISBN 9781118474853. Archived from the original on 2017-09-05.

- Taverny G, Mimouni Y, LeDigarcher A, Chevalier P, Thijs L, Wright JM, Gueyffier F (March 2016). "Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy for prevention of sudden cardiac death in hypertensive individuals". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD011745. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011745.pub2. PMID 26961575.

- Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D, Parr M, Flabouris A, Hillman K (September 2004). "A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom—the ACADEMIA study". Resuscitation. 62 (3): 275–82. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.05.016. PMID 15325446.

- Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hammill SC, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Newby LK, Page RL, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO, Smith SC, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Buller CE, Creager MA, Ettinger SM, Faxon DP, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Tarkington LG, Yancy CW (May 2008). "ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices): developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery and Society of Thoracic Surgeons". Circulation. 117 (21): e350-408. doi:10.1161/CIRCUALTIONAHA.108.189742. PMID 18483207.

- Shun-Shin MJ, Zheng SL, Cole GD, Howard JP, Whinnett ZI, Francis DP (June 2017). "Implantable cardioverter defibrillators for primary prevention of death in left ventricular dysfunction with and without ischaemic heart disease: a meta-analysis of 8567 patients in the 11 trials". European Heart Journal. 38 (22): 1738–1746. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx028. PMC 5461475. PMID 28329280.

- Connolly SJ, Hallstrom AP, Cappato R, Schron EB, Kuck KH, Zipes DP, Greene HL, Boczor S, Domanski M, Follmann D, Gent M, Roberts RS (December 2000). "Meta-analysis of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator secondary prevention trials. AVID, CASH and CIDS studies. Antiarrhythmics vs Implantable Defibrillator study. Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg . Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study". European Heart Journal. 21 (24): 2071–8. doi:10.1053/euhj.2000.2476. PMID 11102258.

- Kaneshiro NK (2 August 2011). "Omega-3 fatty acids". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- Rizos EC, Ntzani EE, Bika E, Kostapanos MS, Elisaf MS (September 2012). "Association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and risk of major cardiovascular disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 308 (10): 1024–33. doi:10.1001/2012.jama.11374. PMID 22968891.

- American Heart Association (May 2006). "2005 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiovascular care (ECC) of pediatric and neonatal patients: pediatric advanced life support". Pediatrics. 117 (5): e1005-28. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0346. PMID 16651281. S2CID 46720891.

- "AHA Releases 2015 Heart and Stroke Statistics | Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation". www.sca-aware.org. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Mutchner L (January 2007). "The ABCs of CPR—again". The American Journal of Nursing. 107 (1): 60–9, quiz 69–70. doi:10.1097/00000446-200701000-00024. PMID 17200636.

- Resuscitation Council (UK). "Pre-hospital cardiac arrest" (PDF). www.resus.org.uk. p. 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Resuscitation Council (UK) (5 September 2012). "Comments on the duration of CPR following the publication of 'Duration of resuscitation efforts and survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study' Goldberger ZD et al. Lancet". Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Gent LM, Atkins DL, Bhanji F, Brooks SC, de Caen AR, Donnino MW, Ferrer JM, Kleinman ME, Kronick SL, Lavonas EJ, Link MS, Mancini ME, Morrison LJ, O'Connor RE, Samson RA, Schexnayder SM, Singletary EM, Sinz EH, Travers AH, Wyckoff MH, Hazinski MF (November 2015). "Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S315-67. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000252. PMID 26472989.

- Simons, Reed W.; Rea, Thomas D.; Becker, Linda J.; Eisenberg, Mickey S. (September 2007). "The incidence and significance of emesis associated with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest". Resuscitation. 74 (3): 427–431. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.01.038. ISSN 0300-9572. PMID 17433526.

-

Voss, Sarah; Rhys, Megan; Coates, David; Greenwood, Rosemary; Nolan, Jerry P.; Thomas, Matthew; Benger, Jonathan (2014-12-01). "How do paramedics manage the airway during out of hospital cardiac arrest?". Resuscitation. 85 (12): 1662–1666. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.09.008. ISSN 1873-1570 0300-9572, 1873-1570 Check

|issn=value (help). PMC 4265730. PMID 25260723. Retrieved 2019-03-04. - Root, Christopher W.; Mitchell, Oscar J. L.; Brown, Russ; Evers, Christopher B.; Boyle, Jess; Griffin, Cynthia; West, Frances Mae; Gomm, Edward; Miles, Edward; McGuire, Barry; Swaminathan, Anand; St George, Jonathan; Horowitz, James M.; DuCanto, James (2020-03-01). "Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD): A technique for improved emergency airway management". Resuscitation Plus. 1–2: 100005. doi:10.1016/j.resplu.2020.100005. ISSN 2666-5204. Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- White L, Melhuish T, Holyoak R, Ryan T, Kempton H, Vlok R (December 2018). "Advanced airway management in out of hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 36 (12): 2298–2306. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.09.045. PMID 30293843. S2CID 52931036.

- Studnek JR, Thestrup L, Vandeventer S, Ward SR, Staley K, Garvey L, Blackwell T (September 2010). "The association between prehospital endotracheal intubation attempts and survival to hospital discharge among out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients". Academic Emergency Medicine. 17 (9): 918–25. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00827.x. PMID 20836771.

- Zhan L, Yang LJ, Huang Y, He Q, Liu GJ (March 2017). "Continuous chest compression versus interrupted chest compression for cardiopulmonary resuscitation of non-asphyxial out-of-hospital cardiac arrest". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD010134. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010134.pub2. PMC 6464160. PMID 28349529.

- Huang Y, He Q, Yang LJ, Liu GJ, Jones A (September 2014). "Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) plus delayed defibrillation versus immediate defibrillation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD009803. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009803.pub2. PMC 6516832. PMID 25212112.

- Lavonas EJ, Drennan IR, Gabrielli A, Heffner AC, Hoyte CO, Orkin AM, Sawyer KN, Donnino MW (November 2015). "Part 10: Special Circumstances of Resuscitation: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S501-18. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000264. PMID 26472998.

- de Caen AR, Berg MD, Chameides L, Gooden CK, Hickey RW, Scott HF, Sutton RM, Tijssen JA, Topjian A, van der Jagt ÉW, Schexnayder SM, Samson RA (November 2015). "Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S526-42. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000266. PMC 6191296. PMID 26473000.

- Zoll AED Plus Archived 2011-06-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Lyon RM, Cobbe SM, Bradley JM, Grubb NR (September 2004). "Surviving out of hospital cardiac arrest at home: a postcode lottery?". Emergency Medicine Journal. 21 (5): 619–24. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.010363. PMC 1726412. PMID 15333549.

- Olasveengen TM, Sunde K, Brunborg C, Thowsen J, Steen PA, Wik L (November 2009). "Intravenous drug administration during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized trial". JAMA. 302 (20): 2222–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1729. PMID 19934423.

- Lin S, Callaway CW, Shah PS, Wagner JD, Beyene J, Ziegler CP, Morrison LJ (June 2014). "Adrenaline for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Resuscitation. 85 (6): 732–40. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.03.008. PMID 24642404.

- Laina A, Karlis G, Liakos A, Georgiopoulos G, Oikonomou D, Kouskouni E, Chalkias A, Xanthos T (October 2016). "Amiodarone and cardiac arrest: Systematic review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Cardiology. 221: 780–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.138. PMID 27434349.

- McLeod SL, Brignardello-Petersen R, Worster A, You J, Iansavichene A, Guyatt G, Cheskes S (December 2017). "Comparative effectiveness of antiarrhythmics for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". Resuscitation. 121: 90–97. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.10.012. PMID 29037886.

- Ali MU, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Kenny M, Raina P, Atkins DL, Soar J, Nolan J, Ristagno G, Sherifali D (November 2018). "Effectiveness of antiarrhythmic drugs for shockable cardiac arrest: A systematic review" (PDF). Resuscitation. 132: 63–72. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.08.025. PMID 30179691.

- Holmberg, Mathias J.; Issa, Mahmoud S.; Moskowitz, Ari; Morley, Peter; Welsford, Michelle; Neumar, Robert W.; Paiva, Edison F.; Coker, Amin; Hansen, Christopher K.; Andersen, Lars W.; Donnino, Michael W.; Berg, Katherine M.; Böttiger, Bernd W.; Callaway, Clifton W.; Deakin, Charles D.; Drennan, Ian R.; Nicholson, Tonia C.; Nolan, Jerry P.; O’Neil, Brian J.; Parr, Michael J.; Reynolds, Joshua C.; Sandroni, Claudio; Soar, Jasmeet; Wang, Tzong-Luen (June 2019). "Vasopressors during adult cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Resuscitation. 139: 106–121. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.04.008. PMID 30980877.

- Vargas, M; Buonanno, P; Iacovazzo, C; Servillo, G (4 November 2019). "Epinephrine for out of hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Resuscitation. 145: 151–157. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.10.026. PMID 31693924.

- Aves, T; Chopra, A; Patel, M; Lin, S (27 November 2019). "Epinephrine for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Critical Care Medicine. 48: 225–229. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004130. PMID 31789700. S2CID 208537959.

- Belletti A, Benedetto U, Putzu A, Martino EA, Biondi-Zoccai G, Angelini GD, Zangrillo A, Landoni G (May 2018). "Vasopressors During Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials" (PDF). Critical Care Medicine. 46 (5): e443–e451. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003049. PMID 29652719. S2CID 4851288.

- Attaran RR, Ewy GA (July 2010). "Epinephrine in resuscitation: curse or cure?". Future Cardiology. 6 (4): 473–82. doi:10.2217/fca.10.24. PMID 20608820.

- Velissaris D, Karamouzos V, Pierrakos C, Koniari I, Apostolopoulou C, Karanikolas M (April 2016). "Use of Sodium Bicarbonate in Cardiac Arrest: Current Guidelines and Literature Review". Journal of Clinical Medicine Research. 8 (4): 277–83. doi:10.14740/jocmr2456w. PMC 4780490. PMID 26985247.

- Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Kudenchuk PJ, Ornato JP, McNally B, Silvers SM, Passman RS, White RD, Hess EP, Tang W, Davis D, Sinz E, Morrison LJ (November 2010). "Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S729-67. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. PMID 20956224.

- Sanfilippo F, Corredor C, Santonocito C, Panarello G, Arcadipane A, Ristagno G, Pellis T (October 2016). "Amiodarone or lidocaine for cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Resuscitation. 107: 31–7. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.07.235. PMID 27496262.

- Perrott J, Henneberry RJ, Zed PJ (December 2010). "Thrombolytics for cardiac arrest: case report and systematic review of controlled trials". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 44 (12): 2007–13. doi:10.1345/aph.1P364. PMID 21119096. S2CID 11006778.

- Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Gent LM, Atkins DL, Bhanji F, Brooks SC, de Caen AR, Donnino MW, Ferrer JM, Kleinman ME, Kronick SL, Lavonas EJ, Link MS, Mancini ME, Morrison LJ, O'Connor RE, Samson RA, Schexnayder SM, Singletary EM, Sinz EH, Travers AH, Wyckoff MH, Hazinski MF (November 2015). "Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S315-67. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000252. PMID 26472989.

- Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest : clinical application and management. Lundbye, Justin B. London: Springer. 2012. ISBN 9781447129509. OCLC 802346256.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Loertscher L, Reed DA, Bannon MP, Mueller PS (January 2010). "Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders: a guide for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. 123 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.029. PMID 20102982.

- Knox C, Vereb JA (December 2005). "Allow natural death: a more humane approach to discussing end-of-life directives". Journal of Emergency Nursing. 31 (6): 560–1. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2005.06.020. PMID 16308044.

- Millin MG, Comer AC, Nable JV, Johnston PV, Lawner BJ, Woltman N, Levy MJ, Seaman KG, Hirshon JM (November 2016). "Patients without ST elevation after return of spontaneous circulation may benefit from emergent percutaneous intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Resuscitation. 108: 54–60. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.09.004. PMID 27640933.

- Lehot JJ, Long-Him-Nam N, Bastien O (December 2011). "[Extracorporeal life support for treating cardiac arrest]". Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine. 195 (9): 2025–33, discussion 2033–6. doi:10.1016/S0001-4079(19)31894-1. PMID 22930866.

- Camuglia AC, Randhawa VK, Lavi S, Walters DL (November 2014). "Cardiac catheterization is associated with superior outcomes for survivors of out of hospital cardiac arrest: review and meta-analysis". Resuscitation. 85 (11): 1533–40. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.08.025. PMID 25195073.

- Cave DM, Gazmuri RJ, Otto CW, Nadkarni VM, Cheng A, Brooks SC, Daya M, Sutton RM, Branson R, Hazinski MF (November 2010). "Part 7: CPR techniques and devices: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S720-8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970970. PMC 3741663. PMID 20956223.

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P (March 2017). "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 135 (10): e146–e603. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. PMC 5408160. PMID 28122885.

- Kusumoto FM, Bailey KR, Chaouki AS, Deshmukh AJ, Gautam S, Kim RJ, Kramer DB, Lambrakos LK, Nasser NH, Sorajja D (September 2018). "Systematic Review for the 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death". Circulation. 138 (13): e392–e414. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000550. PMID 29084732.

- Medicine, Institute of (2015-06-30). Strategies to Improve Cardiac Arrest Survival: A Time to Act. doi:10.17226/21723. ISBN 9780309371995. PMID 26225413.

- Jollis JG, Granger CB (December 2016). "Improving Care of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: Next Steps". Circulation. 134 (25): 2040–2042. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025818. PMID 27994023.

- Daya MR, Schmicker R, May S, Morrison L (2015). "Current burden of cardiac arrest in the United States: report from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium. Paper commissioned by the Committee on the Treatment of Cardiac Arrest: Current Status and Future Directions" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - de Caen AR, Berg MD, Chameides L, Gooden CK, Hickey RW, Scott HF, Sutton RM, Tijssen JA, Topjian A, van der Jagt ÉW, Schexnayder SM, Samson RA (November 2015). "Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S526-42. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000266. PMC 6191296. PMID 26473000.

- Kronick SL, Kurz MC, Lin S, Edelson DP, Berg RA, Billi JE, Cabanas JG, Cone DC, Diercks DB, Foster JJ, Meeks RA, Travers AH, Welsford M (November 2015). "Part 4: Systems of Care and Continuous Quality Improvement: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S397-413. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000258. PMID 26472992. S2CID 10073267.

- Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Gent LM, Atkins DL, Bhanji F, Brooks SC, de Caen AR, Donnino MW, Ferrer JM, Kleinman ME, Kronick SL, Lavonas EJ, Link MS, Mancini ME, Morrison LJ, O'Connor RE, Samson RA, Schexnayder SM, Singletary EM, Sinz EH, Travers AH, Wyckoff MH, Hazinski MF (November 2015). "Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S315-67. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000252. PMID 26472989.

- Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, Kellermann AL (January 2010). "Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 3 (1): 63–81. doi:10.1161/circoutcomes.109.889576. PMID 20123673.

- Bougouin W, Mustafic H, Marijon E, Murad MH, Dumas F, Barbouttis A, Jabre P, Beganton F, Empana JP, Celermajer DS, Cariou A, Jouven X (September 2015). "Gender and survival after sudden cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Resuscitation. 94: 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.06.018. PMID 26143159.

- Ballew KA (May 1997). "Cardiopulmonary resuscitation". BMJ. 314 (7092): 1462–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7092.1462. PMC 2126720. PMID 9167565.

- van Gijn MS, Frijns D, van de Glind EM, C van Munster B, Hamaker ME (July 2014). "The chance of survival and the functional outcome after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in older people: a systematic review". Age and Ageing. 43 (4): 456–63. doi:10.1093/ageing/afu035. PMID 24760957.

- Cobbe SM, Dalziel K, Ford I, Marsden AK (June 1996). "Survival of 1476 patients initially resuscitated from out of hospital cardiac arrest". BMJ. 312 (7047): 1633–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7047.1633. PMC 2351362. PMID 8664715.

- Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA (October 2001). "Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998". Circulation. 104 (18): 2158–63. doi:10.1161/hc4301.098254. PMID 11684624.

- "Abstract 969: Lifetime Risk for Sudden Cardiac Death at Selected Index Ages and by Risk Factor Strata and Race: Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project – Lloyd-Jones et al. 120 (10018): S416 – Circulation". Archived from the original on 2011-06-08.

- Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier.

- Porter I, Vacek J (May 2008). "Single ventricle with persistent truncus arteriosus as two rare entities in an adult patient: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2: 184. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-184. PMC 2424060. PMID 18513397.

- Buxton AE, Calkins H, Callans DJ, DiMarco JP, Fisher JD, Greene HL, Haines DE, Hayes DL, Heidenreich PA, Miller JM, Poppas A, Prystowsky EN, Schoenfeld MH, Zimetbaum PJ, Heidenreich PA, Goff DC, Grover FL, Malenka DJ, Peterson ED, Radford MJ, Redberg RF (December 2006). "ACC/AHA/HRS 2006 key data elements and definitions for electrophysiological studies and procedures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (ACC/AHA/HRS Writing Committee to Develop Data Standards on Electrophysiology)". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 48 (11): 2360–96. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.020. PMID 17161282.

- "Slow Codes, Show Codes and Death". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. 22 August 1987. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- "Decision-making for the End of Life". Physician Advisory Service. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. May 2006. Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2013-04-06.CS1 maint: others (link)

- DePalma JA, Ozanich E, Miller S, Yancich LM (November 1999). ""Slow" code: perspectives of a physician and critical care nurse". Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 22 (3): 89–97. doi:10.1097/00002727-199911000-00014. PMID 10646457. Archived from the original on 2013-03-28. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

External links

| Classification |

|---|