Philippines–United States Visiting Forces Agreement

The Philippines–United States Visiting Forces Agreement, sometimes the PH–US Visiting Forces Agreement, is a bilateral visiting forces agreement between the Philippines and the United States consisting of two separate documents. The first of these documents is commonly referred to as "the VFA" or "VFA-1",[1] and the second as "VFA-2" or "the Counterpart Agreement".[2] A visiting forces agreement is a version of a status of forces agreement that only applies to troops temporarily in a country. The agreements came into force on May 27, 1999, upon ratification by the Senate of the Philippines.[3][8], [10] The United States government regards these documents to be executive agreements not requiring approval by the United States Senate.[3][42]

| Type | Visiting forces agreement |

|---|---|

| Effective | May 27, 1999 |

| Expiration | Suspended |

| Parties |

_before_they_depart_the_island.jpg.webp)

Provisions

The primary effect of the Agreement is that it allows the U.S. government to retain jurisdiction over U.S. military personnel accused of committing crimes in the Philippines, unless the crimes are "of particular importance to the Philippines".[1] This means that for crimes without this significance, the U.S. can refuse to detain or arrest accused personnel, or may instead prosecute them under U.S. jurisdiction. Under the Visiting Forces Agreement, the local courts have one year to complete any legal proceedings.[4] The Agreement also exempts U.S. military personnel from visa and passport regulations in the Philippines.

The Agreement contains various procedural safeguards which amongst other things establish the right to due process and proscribe double jeopardy. The Agreement also prevents U.S. military personnel from being tried in Filipino religious or military courts[1][V 11]; requires both governments to waive any claims concerning loss of materials (though it does require that the U.S. honor contractual arrangements and comply with U.S. law regarding payment of just and reasonable compensation in settlement of meritorious claims for damage, loss, personal injury or death, caused by acts or omissions of United States personnel)[1][VI]; exempts material exported and imported by the military from duties or taxes[1][VII]; and allows unrestricted movement of U.S. vessels and aircraft in the Philippines.[1][VIII]

Subic rape accusation

The U.S. has at least twice used the Agreement to keep accused military personnel under U.S. jurisdiction.[5][6] On January 18, 2006, the U.S. military maintained custody of four troops accused of rape while visiting Subic Bay during their trial by a Philippine court.[6] They were held by American officials at the United States Embassy in Manila. This led to protests by those who believe that the agreement is one-sided, prejudicial, and contrary to the sovereignty of the Philippines. The agreement has been characterized as granting immunity from prosecution to U.S. military personnel who commit crimes against Filipinos,[7] and as treating Filipinos as second class citizens in their own country.[8][9] As a result of these issues, in 2006, some members of the Philippine Congress considered terminating the VFA.[10][11] However, the agreement was not changed.

Death of Jennifer Laude

A second Philippine court case under the VFA is the one following the death of Jennifer Laude, also involving a U.S. Navy ship docked at Subic Bay. This case happened after the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement was signed.

Supreme Court cases

The constitutionality of the VFA was challenged twice. The case Bayan v. Zamora was dismissed on October 10, 2000 by the Supreme Court of the Philippines, sitting en banc.[12]

The second challenge, Suzette Nicolas y Sombilon Vs. Alberto Romulo, et al. / Jovito R. Salonga, et al. Vs. Daniel Smith, et al. / Bagong Alyansang Makabayan, et al. Vs. President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, et al. submitted on January 2, 2007, was decided on February 11, 2009, again by the Supreme Court sitting en banc. In deciding this second challenge, the court ruled 9–4 (with two justices inhibiting) that, "The Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) between the Republic of the Philippines and the United States, entered into on February 10, 1998, is UPHELD as constitutional, ...". The decision continued, specifically relating to matters relevant to the Subic Rape Case, "... the Romulo-Kenney Agreements of December 19 and 22, 2006 are DECLARED not in accordance with the VFA, and respondent Secretary of Foreign Affairs is hereby ordered to forthwith negotiate with the United States representatives for the appropriate agreement on detention facilities under Philippine authorities as provided in Art. V, Sec. 10 of the VFA, pending which the status quo shall be maintained until further orders by this Court."[13] UP Professor Harry Roque, counsel for former senator Jovito Salonga, one of the petitioners in the case, said in a phone interview regarding the decision on the constitunality of the VFA. "We will appeal, ... We are hoping we could convince the other justices to join the four dissenters."[14]

Counterpart agreement

The primary effect of the agreement is to require the U.S. government to notify Philippine authorities when it becomes aware of the apprehension, arrest or detention of any Philippine personnel visiting the U.S. and, when so requested by the Philippine government, to ask the appropriate authorities to waive jurisdiction in favor of the Philippines, except in cases of special interest to the U.S. Departments of State or Defense.[2][VIII 1] Waiving of jurisdiction in the U.S. is complicated because the United States is a federation of U.S. states and therefore a federation of jurisdictions.

The agreement contains various procedural safeguards to protect rights to due process and proscribe double jeopardy.[2][VIII 2–6] The agreement also exempts Philippine personnel from visa formalities and guarantees expedited entry and exit processing;[2][IV] requires the U.S. to accept Philippine drivers licenses;[2][V] allows Philippine personnel to carry arms at U.S. military installations while on duty;[2][VI] provides personal tax exemptions and import/export duty exclusions for Philippine personnel;[2][X, XI] requires the U.S. to provide health care to Philippine personnel;[2][XIV] and exempts Philippine vehicles, vessels, and aircraft from landing or ports fees, navigation or overflight charges, road tolls or any other charges for the use of U.S. military installations.[2][XV]

Status of the agreement

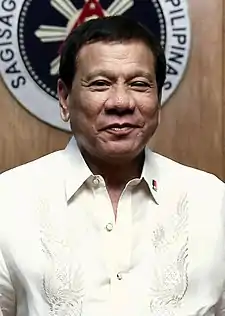

On February 11, 2020, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte formally announced to the United States embassy in Manila that he was ending the pact, with termination to take effect in 180 days unless agreed otherwise during that time. Duterte has in the past shown admiration for both the Russian Armed Forces, as well as the Chinese People's Liberation Army, despite the fact that the Philippines and China are embroiled in a dispute in the South China Sea regarding sovereignty over the Spratly Islands.[15] In June 2020, the Philippine government reversed this decision and announced that it would maintain the agreement.[16] In November, 2020, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte ordered an extra six months “To enable us to find a more enhanced, mutually beneficial, mutually agreeable, and more effective and lasting arrangement on how to move forward in our mutual defense”.[17]

See also

References

- "Agreement Regarding the Treatment of US Armed Forces Visiting the Philippines". ChanRobles Law Library. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- "Agreement Regarding the Treatment of RP Personnel Visiting the USA". ChanRobles Law Library. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- "G.R. No. 138570. October 10, 2000". Supreme Court of the Philippines. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- "Court enters not guilty plea for Pemberton in Laude murder case". GMA News. February 23, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- "Filipino taxi driver drops charges against U.S. servicemen". Asian Economic News. 2000. Retrieved September 18, 2006.

- "Philippine prosecutors file rape charges against 4 U.S. Marines". Asian Economic News. December 27, 2005. Retrieved September 17, 2006.

- "Aquino rejects scrapping of VFA". The Manila Times. October 21, 2014.

- "'Nicole' a scapegoat to save VFA – lawmaker". ABS-CBN News. March 18, 2009.

- "Woman Who Accused U.S. Marine of Rape Changes Her Story; Critics See A Conspiracy". CNSNews.com. March 19, 2009.

- Philip C. Tubeza; Michael Lim Ubac (January 19, 2006). "Angry lawmakers in Senate, House move to terminate VFAvisiting forces agree,ent". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- "LEGISLATIVE OVERSIGHT ON THE VISITING FORCES AGREEMENT (LOVFA)" (PDF). Philippine Senate. December 17, 2004.

- G.R. No. 138570, October 10, 2000, 342 SCRA 449, archived from the original on July 26, 2009, retrieved February 11, 2009.

- G.R. No. 175888, February 10, 1998.

- Edu Punay (February 12, 2009), "SC orders transfer of US Marine rapist to RP jail", Philippine Star, archived from the original on January 4, 2013, retrieved February 11, 2009

- Gomez, Jim (February 11, 2020). "Philippines intends to end major security pact with the U.S." PBS NewsHour via the Associated Press.

- "Philippines Backs Off Threat to Terminate Military Pact With U.S." The New York Times. June 2, 2020.}}

- "Philippines extends termination process of U.S. troop deal, eyes long-term defence pact". Reuters. November 11, 2020.

Further reading

- Dieter Fleck, ed. (September 18, 2003). The Handbook of The Law of Visiting Forces. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826894-9.

External links

- "VFA FAQ". Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved December 25, 2006.

- "VFA PRIMER". Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2006.

- "Facts about the U.S.-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement". Embassy of the United States in Manila. January 20, 2006. Archived from the original on January 22, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2006.

- "1951 PH/US Mutual Defense Treaty". ChanRobles Law Library. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- "U.S.-Philippine Joint Statement on Defense Alliance" (Press release). The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. November 20, 2001. Retrieved December 26, 2006.