Qianzhuang

Qianzhuang (Chinese: 錢莊; Wade–Giles: ch'ien-chuang), alternatively known as qiansi (錢肆), qianpu (錢鋪), yinhao (銀號), duihuan qianzhuang (兌換錢莊), qiandian (錢店), qianzhuo (錢桌), duidian (兌店, "exchange office"), qianju (錢局), yinju (銀局), or yinpu (銀鋪) in Mandarin Chinese, and translated as money shops, native banks, private Chinese banks, or old-style banks in English, were a large number of small native Chinese banks that operated independently of the nationwide network of Shanxi banks (票號, piaohao), these banks first sprung up during the Ming dynasty but greatly expanded during the Qing dynasty. Unlike the Shanxi banks, the qianzhuang tended to have much more risky business practices.[1]

These institutions first appeared in the Yangzi Delta region, in Shanghai, Ningbo, and Shaoxing. The first qianzhuang can be traced to at least the mid-eighteenth century. In 1776, several of these banks in Shanghai organised themselves into a guild under the name of qianye gongsuo.[2] In contrast to piaohao, most qianzhuang were local and functioned as commercial banks by conducting local money exchange, issuing cash notes, exchanging bills and notes, and discounting for the local business community. Qianzhuang maintained close relationships with Chinese merchants, and grew with the expansion of China's foreign trade. When Western banks first entered China, they issued "chop loans" (彩票, caipiao) to the qianzhuang, who would then lend this money to Chinese merchants who used it to purchase goods from foreign firms. During the latter half of the 19th century the qianzhuang worked as intermediaries between Chinese merchants and foreign banks. Unlike the Shanxi banks the qianzhuang survived the fall of the Qing dynasty because of their close relationships with foreign banks. The qianzhuang have always been a true financial service provider for Chinese agribusiness and commercial households. The control of deposit and loan risk in the qianzhuang business model is a concentrated expression of the localisation advantages of qianzhuang.

It is estimated that there were around 10,000 qianzhuang in China in the early 1890s.[3][4] There were several financial crashes which occurred in China during which a large number of qianzhuang closed, the largest of these occurred in the years 1883, 1910, and 1911. By and by the traditional qianzhuang banks were being replaced by modern credit banks in China, particularly those residing in Shanghai. This would continue to happen well into the Republican period. The last qianzhuang banks were nationalised in 1952 by the government of the People's Republic of China.[5]

During the 1990s qianzhuang made a come back in Mainland China, these new qianzhuang are informal financial companies which are often operating just within the edges of what is legal. The government attitude towards these new qianzhuang isn't that much different from their attitude in the 1950s.

Regional names for private banks in China

qianzhuang had a variety of regional names across China, these names differed from region to region and were sometimes included in the official name of the local company. The name qianzhuang was typically used for banks and bank-like institutions in the region around the lower Yangtze river. The terms yinhao and qianpu were more typically used in Northern China especially in cities like Beijing, Tianjin, Shenyang, Jinan, and Zhengzhou.[6] In southern China qianzhuang was also often called qianju or qiandian (both of which could be translated as "money store").[7] Meanwhile, all terms were used in the cities of Xuzhou, Hankou, Chongqing, and Chengdu.[6] In Hankou alone the qianzhuang were referred to by a long list of aliases including qianpu, qianzhuo, qiantan, yinju, yinlou, yinpu, and yin lufang in the local archives.[7]

The larger native Chinese banks in the treaty port city of Shanghai were called huihuazhuang (匯劃莊, "credit banks"), da tonghang (大同行), or ruyuan qianzhuang (入園錢莊), these banks were members of the head office of the monetary business or the qianye zonggong suo (錢業總公所) in Mandarin Chinese. Separate terms existed for the smaller native Shanghainese financial institutions such as fei huihuazhuang (非匯劃莊 "non-credit banks") or xiao tonghang (小同行).[6]

In the local archives, the Hankou qianzhuang were divided into two major groups: one of these groups included the larger qianzhuang called Zihao, and the other group included the smaller qianzhuang of Hankou and was referred to as Menmian. This Menmian-Zihao division was loosely based on several factors such as their locations, trade sizes or scopes. The word Zihao verbatim means "name-brand" in English, while the word Menmian could be translated as "store-front". The nominal requirement for registration of a Zihao was to submit the signatures of 2 to 5 baoren (保人), as the newcomer's sureties, these baoren already had their business or businesses registered.[7] The Zihao usually would demand more capital and better reputation as they engaged in more and wider note-transactions and would issue larger credit-loans. The Zihao formally established an initiation board for registration arrangements and other managerial issues. While the Zihao opened mostly in quiet alleys, the Menmian were located more in thoroughfares or more heavily crowded lanes, these locations tended to be more convenient for services such as money exchange and petty loans service.[7]

Shanxi banks were another form of private banks in China which were locally known as piaohao (票號, "draft banks"). The Shanxi banks are often separated from qianzhuang by many scholars who study the economic history of China. But some scholars instead combine the piaohao with the qianzhuang, as the distinction between them is seen more like a franchise strategy that was applied by the Shanxi merchants, this strategy was similar to that by merchants from other Chinese regions like Wuxi in the Jiangsu province and Ningbo in the Zhejiang province, the claiming initiator and dominator of Shanghai qianzhuang banks.[7]

Structure of the qianzhuang

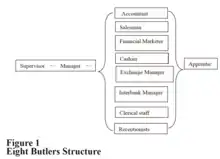

The basic organisational structure of the qianzhuang was based on a system known as the "Eight Butlers structure", in this structure the qianzhuang was led by the manager and his associates as well as a supervisor, the subordinate staff consisted of employees which were collectively known as the "Eight Butlers", these "Eight Butlers" include accountants, cashier, clerical staff, exchange managers, financial marketers, interbank managers, receptionists, and salesmen. These staff members all had their own apprentices subordinate to them. What rank each staff member had within each qianzhuang was very dependent on the needs and business strategy of every individual qianzhuang, for example a qianzhuang with low funds was more dependent on their interbank manager lending money, but qianzhuang that were richer tended to place the salesmen at the top of the "Eight Butlers" hierarchy because they were more important in expanding their business and other positions like that of interbank manager was placed second and that of accountant third.

The most important and powerful staff member of a qianzhuang was the manager who was responsible for most decisions that were made by the bank such as dealing with daily trifles, business transactions, and the transfer of staff members. Because of the power the manager held the shareholders had to make sure that they'd always hire the most qualified individual for the task, as this job required a great deal of trust and the selection process had to be done as carefully as possible to ensure that the most qualified manager headed the operation. Some shareholders would appoint supervisors to supervise these managers to make sure that they always had the best interest of the shareholders in mind and could report anything to the shareholders at any time.

Many qianzhuang also hired several associates to assist the manager, and the number of staff from each position as low as apprentice to as high as manager was never certain, as all employees are shifted according to both the scale and the focus of the business. Staff members of a qianzhuang were either hired directly by the shareholders or were recommended by managers. It is only natural that such an organisational structure can not only maintain the authority of the management, but could also implement policies and guidelines effectively. This structure also allowed for there to be plenty of flexibly so the qianzhuang were highly adaptable to changing circumstances. There were not only checks and balances between the same level of authority, but there were also a number of supervisory constraints between the upper and lower levels of the staff, this was done as a way to enhance the ability of qianzhuang enterprises to withstand more risks.

As long as the owner of a qianzhuang would file for registration and pay their fees, or skip both of these steps entirely, employed a staff, and would join the local qianzhuang guild then they were ready for operating their business. The average qianzhuang officially employed around and usually less than thirty people plus apprentices. While their earnings were audited every year their profits normally distributed only every 3 years.[7]

This could lead to misconducts or embezzlement; thus the intervals of internal auditing and dividend distributing were synchronized afterwards. The western double-entry method was slowly adapted to replace the traditional ones. Usually around ⅔ of the net earnings went to owners of the business, and the remaining profits went to employees, but the chief manager would still decide how to distribute the bonus packages. Normally, the chief manager would take 20% to 30% of the total bonus; the others shared the rest based on both performance and their status within the company hierarchy.[7]

It was common that a reputed manager could run several qianzhuang at the same time as long as the owners of these businesses consensually agreed upon the arrangement.[7]

Between the years of 1926 and 1927 a large percentage of the qianzhuang of Hankou shifted their structures of ownership, nominally these qianzhuang held an unlimited liability, but many of them evolved from sole-proprietorship to partnerships.[7] This change in model could be explained by several events such as the 1926 Northern Expedition by the Kuomintang, their purging of Communists, the Kuomintang occupation of Hankou in 1927, and the Nanchang Uprising in Jiangxi, as well as the Autumn Harvest Uprising in Hunan by the communists. These events all lead to the Hankou qianzhuang to form more alliances, the business model created from this situation was known as the "armpit partnership". The "armpit partnership" was designed as a way to avoid head-counting trade censuses by the local authorities.[7]

The creation of the "armpit partnership" model allowed for those who wished to avoid any attention by the authorities to join the very lucrative qianzhuang business. A united voice of "armpit partners" also had the power to protect their pecuniary interests from being funnelled to the dominating partners. This model of "armpit partnerships" would serve a defensive mechanism (or a modus vivendi), enticing the Hankou qianzhuang to make more business allies under political gauntlets.[7]

Lending out money is the greatest source of risk that these traditional bank faced in China. If the loan was steady then the risk would be greatly reduced, the paramount key to the risk control that a qianzhuang could have is by lending only to trustworthy people.

The qianzhuang employed a special type of personnel selection and hiring system. A qianzhuang generally had a rather strong family(-like) style about personnel arrangements and how they would function. The selection process of shareholders, managers, and even apprentices is rooted in the Chinese tradition of "consanguinity, kinship, geographic, and professional affinity", this system is called a "pan-family" relationship network.

It is in fact because of this "pan-family" relationship network family-like personnel mechanism, that qianzhuang with their rather less rigorous internal control systems seemed to have reduced occurrences of internal risks due to their own staff. If the managers were not personally close to the shareholders who owned the qianzhuang in their "pan-family" relationship network, then they would mostly be selected from the three year qianzhuang apprentice programmes or from other employees, and most of these staff members also tended to have "pan-family" relationships with shareholders. In fact there were strong "pan-family" tendencies in the selection processes and the appointment of various other positions at most qianzhuang, these included things such as recruiting apprentices, introducing relatives and friends to the qianzhuang, training exchange students from other regions, etc. Through this "pan-family" personnel system, the bankers of a qianzhuang were not just considered to be "only doing a job", but they were also seen as "standing for the family".

Qianzhuang guilds

In traditional Chinese society, the number of qianzhuang is generally more than 10, this was even the case in an ordinary city, because of the large number of qianzhuang in China, there was usually exists guild within the scope of the city.

Hankou

The Hankou qianzhuang guilds were established sometime before or in the year 1894 as mediators for the Hankou qianzhuang as the high number of qianzhuang made the scene overcrowded. In Hankou two separate guilds for the qianzhuang coexisted simultaneously, one was called the Qianye Gonghui (錢業公匯) and the other was named the Qianye Gongsuo (錢業公所, "money industry office"). The Qianye Gongsuo concerned itself only with Confucian rituals and ritualistic events while the Qianye Gonghui handled all mundane issues. These rituals performed by the Qianye Gongsuo were practiced to evince ancestral respects, something highly valued by the Confucian community.[7]

Both Hankou guilds did not show any signs of competition but tended to have a sense of mutual support. During the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 the workplace of the Qianye Gonghui was completely burnt to ground, but it could still have its regular function maintained in the temple joss hall, which was loaned by the Qianye Gongsuo, which managed to survive the chaos of the uprising. The average interval time of draft-exchange business was 5 to 15 days; then it was converted to a daily base after 1911 to satisfy expanding monetary and fiscal transactions done by the Hankou qianzhuang. The Qianye Gongsuo, and its duties, was gradually merged into the Qianye Gonghui during the early Chinese Republican period.[7] During the financial chaos from 1907 to 1908, the Hankou qianzhuang managed to restore themselves because of the Hankou qianzhuang guild's collective acts. Before its full recuperation, the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 clouted again. But due to actions from the Hankou qianzhuang guild the Hankou qianzhuang experienced another steady recovery from 1911 to 1926. According to records from the municipal archives of Hankou, it is revealed that the Hankou qianzhuang Guild tended to evolve with a series of business booms and busts in the local money market, meaning that it was flexible.[7]

In the year 1929 the Hankou qianzhuang guild gained a self-governing board that was professionally managed. As a part of the reforms affecting the Hankou qianzhuang guild, the member qianzhuang would elect members that would serve in a standing committee to fulfil duties such as planning events, settling disputes, the clearance of trade, publishing flyers, and welfare for the staff. The costs of operating the guild were shares among the qianzhuang which were its members.[7] The Hankou qianzhuang guild distributed its daily market flyyer to the regions surrounding the city on regular basis. Its issuing volume surpassed 20,000 flyers a day. However, this number fell to only 10,000 after the catastrophic flood of 1931 that inundated Hankou and killed more than 30,000 people in two months which also severely affected many of its readership.[7]

The Hankou qianzhuang guild fully funded an affiliated elementary school and a night school for the staff. The employees of the affiliated Hankou qianzhuang could enroll into the guild-maintained night school, while the young relatives of these employees were allowed to go to the affiliated elementary school.[7]

Between the years 1938 and 1945 the city of Hankou was occupied by the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War (which would later become a theatre of World War II), the Hankou qianzhuang guild managed to continue operating despite the foreign occupation. Many local qianzhuang chose to collaborate with the Japanese during the occupation, dozens of these qianzhuang were facing jeopardy following the surrender of Japan in 1945.[7]

Shanghai

In the treaty port city of Shanghai the qianzhuang were all members of a two guilds organised by them based on their location in the city. The guilds responsible for the Shanghai qianzhuang operated as two geographical bodies parallel to each other, the one for northern Shanghai was called the Bei Huiguan (北會館, "Northern guild hall") and the one for southern Shanghai was called the Nan Gongsuo (南公所, "Southern industry office"). These two guilds handled things like the draft-exchange business practiced among their members separately. There was another guild body named the Neiyuan (內園, "inner garden") which coordinated the south–north draft-exchange as a joint agency of both Shanghai qianzhuang guilds.[7]

National guild

In the year 1947 the Shanghai qianzhuang guild invited the guilds from the cities of Hangzhou, Ningbo, Nanjing, Hankou, Chongqing, Beiping, and Tianjin to form a national Chinese qianzhuang guild.[7] This national guild would gain members from 38 other cities in October of the same year as it began to expand, one of the reasons why more cities started joining this national qianzhuang guild was as a defense against the uncontrollable hyperinflation which had struck China during the 1940s following the end of World War II.[7]

The national qianzhuang guild served as a loose coalition and would exist for 5 years before undergoing the same fate as all qianzhuang in China. Some of the efforts of this national Chinese guild include establishing a joint reserve for the issuance of new banknotes by both commercial banks and qianzhuang, however, this proposal never came to fruition due to the chaos of the Chinese Civil War.[7]

Role and liability of shareholders and high risks

In the traditional Chinese banking industry, a system was implemented which was known as the "identity stock system". The "identity stock system" is a system based on profit dividend. When a qianzhuang is profitable, the manager can then share the dividend.

As the shareholders of a qianzhuang offered unlimited liability they were fully liable for any debt the qianzhuang had, even if the qianzhuang was declared bankrupt and was liquidated. When a qianzhuang loses money, especially when it is liquidated, all the debt and losses are borne by the shareholders. The typical qianzhuang is usually highly indebted, and tend to have a capital-to-debt ratio of tens of times. For this reason the credit of qianzhuang to the depositors was not dependent on the amount of equity it had, rather on the abundance degree of the family background of the shareholders, as well as on the operation of any property which they owned. In fact, after a qianzhuang was declared bankrupt those that the qianzhuang still owed money would demand repayment from its shareholders and it wasn't uncommon for the (former) shareholders, even after a year or two after its closure, would still insist on paying qianzhuang's debts. This was also because if they would not pay these debts their "business credit" would also decrease as the shareholders bear unlimited liabilities for the debts of the qianzhuang. When shareholders would invest in a qianzhuang, there had first be a considerable amount of deposits in qianzhuang made by the shareholders.

The way the system was set up was that the credit of a qianzhuang was wholly independent of the equity or capital of the bank itself but was based on the credit of the shareholders themselves as well as the credit of their whole family. The stronger the financial resources of shareholders and their families and the more prominent their credit and reputation in the business world was, the stronger their banking power will be, and by extend the banking power of the qianzhuang. This was also why the debts of a qianzhuang will be distributed by the shareholders based on the percentage of their shares, and the shareholders themselves will be fully responsible for paying the debts. If there is any issue with the qianzhuang, it was customary for the shareholders to pay these off immediately. In the event if of a bank run, it was required for the shareholders to compensate with their own lives. Therefore, the management of managers is to take not just the investments but also the lives of shareholders in the game, the responsibility of the managers in this respect was quite heavy, naturally there was also a high sense of moral responsibility associated with the profession.

When reversal of debt would occur, the debts could not be repaid (for qianzhuang the goals of debt recovery are draft scattered, and those debtors may indeed be no money), but depositors of qianzhuang were hardly likely to push the qianzhuang (meanwhile for depositors the goal of debt recovery is rather obvious and concentrated), together with the support of the Chinese government, a wealthy family of shareholders, within the timeframe of only several days, may ruin all of their fortune and they would become street beggars.

History

Imperial China

The earliest qianzhuang were established during the Ming dynasty. These early private banks would be operate either as a single proprietorship known as duzi (獨資) or as a joint proprietorship known as hehuo (合伙).[6] Most qianzhuang tended to be small proprietorships which had unlimited liability, these local banks were often sparsely aligned along family and linguistic ties and they were rarely patronised by the local government authorities.[8][9] A large number of these early ventures were simply a business that some merchants families kept on the side and a few of them were also seen as an investment of government officials or those who belonged to the landowning gentry.[6] The larger qianzhuang would change money, operate deposits, make loans to traders, care for remittances, and in some cases issue their own scrip known as Zhuangpiao (莊票) and Yinqianpiao (銀錢票, "silver money notes").[6] Larger qianzhuang would issue company scrip against individual deposits, this scrip was also accepted by proximate shops but to cash these out would take around 10–15 days after it was given to the shop, this was because couriers would have to liaise with the issuing shop in order to rule out fraudulent Zhuangpiao notes.[8]

The first documented qianzhuang banking institution of Beijing was the Yinhao Huiguan (銀號會館, "bankers' guild hall"), this bank had a shrine called Zhengyisi (正已祠) in its building, the Yinhao Huiguan was first mentioned in 1667 under the reign of the Manchu Qing dynasty. The first qianzhuang in Shanghai was founded seven decades later in 1736 was named the Qianye Gongsuo (錢業公所, "money industry office").[6] The primary business of the qianzhuang was giving out loans in the Chinese hinterland to promote trade and the exchange of commodities with the coastal regions of China.[8] Many qianzhuang engaged in the business exchanging copper-alloy cash coins and silver sycees and foreign coins and vice versa as China used a bimetallic currency system with fluctuating exchange rates.[6] number of coins in a single string was locally determined as in one district a string could consist of 980 cash coins, while in another district this could only be 965 cash coins, these numbers were based on the local salaries of the qiánpù.[10][11] During the Qing dynasty the qiánpù would often search for older and rarer coins to sell these to coin collectors at a higher price.[12][13][14] Remittances by qianzhuang would be carried out using a vast network of partner institutes, the owners of these other financial institutes would often hail from the same region, yet most of these small private banks would only operate locally.[6] Comparatively, the financial landscape of northern China was very much focused on the imperial Chinese government.[8][15][16] The qianzhuang were the main financial institutions serving as intermediaries between the Europeans and the Chinese for financial purposes.

The qianzhuang had two kinds of their own funds, one is the equity capital, the other is the demand deposit in firm deposited by the owning shareholders, which is called copy or passport. Because the shareholders of a qianzhuang often own many firms, their deposits in one firm are often variable. And the different qianzhuang owned by the same shareholders would often pay for the other's deposits if it had insufficient funds.

Under the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor a central banking institute was founded in the city of Tianjin named the Yinhao Gongsuo (銀號公所).[6]

There were 106 financial institutions founded in the last quarter of the eighteenth century.[6]

Until the Xinhai Revolution deposed of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the dominant financial and banking institutions in China were the Shanxi banks (piaohao, which could be translated as "remittance houses"), the Shanxi banks specialised in long-distance money remittances which they would engage in on behalf of agencies of the Qing government or to dispatch of government officials’ emoluments.[8][17][18] In the middle of the nineteenth century the qianzhuang started making more short-term loans to cash strapped local governments, invested more into national funds, and started issuing shares.[6] The qianzhuang and piaohao ("Shanxi banks") were created out of different circumstances, while the piaohao were created out of a necessity for long-distance remittance, the qianzhuang were originally created for the silver-specie exchange market.[7] Because of this, the scope of business of the qianzhuang was very dissimilar to that of the Shanxi banks, the qianzhuang tended to make their profits from relatively high interest rates which they would charge on unsecured loans to medium-range merchants, while the Shanxi banks subsisted their profits more on draft commission. Because of these different business models, some Shanxi banks were known to deposit some of their idle funds in qianzhuang interest-bearing accounts, this meant that the general relationship between the qianzhuang and the Shanxi banks was one of cooperation and complementarity rather than of confrontational competition.[8] A large bulk of the cash coins the qianzhuang dealt with were inherited from earlier Chinese dynasties, or were re-casted in the furnaces of imperial mints and private franchised furnaces, or illegally elsewhere. The face value of cash coins were often not contingent on intrinsic value of the metal they contained. The silver-purity standards entailed long business disputes, while many local Chinese archives repetitively documented mounting concerns to specie and silver forgeries which circulated at the time. It seems that the primary service of the early qianzhuang involved primarily with the necessity of silver-specie exchange, and thus the market demand created qianzhuang spontaneously.[7]

Through the financial exchanges between qianzhuang and qianzhuang, qianzhuang and piaohao , qianzhuang and domestic and foreign commercial banks, a rather large financial network was established to communicate cross-regional trade and foreign trade within and with the Chinese Empire. The qianzhuang system is one of the most representative forms of business development in imperial China's financial industry. It played an indispensable role in the history of Chinese finance and even the economic history of China, as well as the transition from the traditional Chinese economy model to a more modernised model adopted during the late 19th century.

In Shanghai many qianzhuang were initially created by businessmen from the Zhejiang Province, especially from the city of Ningbo. Many of these businessmen moved their qianzhuang to Shanghai as a method to finance their businesses back home. By the year 1776, under the reign of Qianlong Emperor, The Shanghai qianzhuang owners had established an association in the Yuyuan Garden, with 106 affiliated members.

In the city of Hankou the piaohao were prosperous before the qianzhuang were, this might have been due to connections with the political circle. Less is known about the origins of the Hankou qianzhuang which could be either due to the immense number of aliases used to describe qianzhuang or the fact that the Qing government wasn't good at record keeping during this early era. The trade conducted by qianzhuang in Hankou is locally referred to as Yin-Qian (銀錢).[7] Between the years 1841 and 1850 the Hankou qianzhuang were dominated by merchants from the Jiangxi province, the larger qianzhuang from this era had an average benqian (本錢, "principal capital") which ranged between 6000 and 10,000 taels of silver, and on average they issued hundreds of thousands of Huapiao (匯票, "remittance notes") banknotes for circulation.[7]

The economic centre of gravity of the Qing dynasty began to shift during the 1850s from the port of Guangzhou, Guangdong to Shanghai.[8] During the chaos of the Taiping Rebellion many Chinese government officials and affluent landlords were forced to flee their lands as it was being occupied by the advancing Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, many of these refugees would flee to the Bund in Shanghai's foreign concessions. This led to the qianzhuang of Shanghai in taking up real estate investment and stock exchange speculation expanding and diversifying their business scope.[8] During the 1860s the qianzhuang of Shanghai started looking to the foreign banking companies[lower-alpha 1] as a source of capital.[8] As foreign banks began investing more into the Chinese market, these foreign banking companies would fulfill the need for money that local Chinese banks had at the time by issuing short-term loans known as zhekuan (拆款, "interbank loans") to them. These loans were necessary as monetary volume of most qianzhuang banks usually was around 70,000 taels of silver or less. By the year 1888 sixty two of the largest qianzhuang had engaged in borrowing millions of taels in silver in loans from foreign banks on a yearly basis. The Qianzhuang on-lent funds from foreign banking companies to Chinese traders and merchants who engaged in the wholesale of imported products until these merchants would sell their stock and were able to pay off their debts. This method of on-call credit from foreign banks were known as chop loans (彩票, chaipiao).[8][19][20] This newfound relationship between the qianzhuang and foreign banks would be mutually beneficial as this allowed for the traditional Chinese banks to serve as intermediaries between them and Chinese merchants or the Qing government making them invaluable for foreigners doing business in China.[6]

European and Japanese banks had the ability to readily lay down funds in the Chinese treaty ports because these banks had established exclusive relationships with native foreign trading houses. These foreign trading houses in China were ever ready to exchange local money for sterling notes. Compared to the diffuse qianzhuang, these foreign banks were otherwise much better capitalised, this meant that the monetary credit that they advanced reinvigorated the foreign trade at the Chinese treaty ports, which would often lapse into patterns of barter.[8][21][22]

The Sino-French War between 1883 and 1885 had many Chinese people to run on the qianzhuang to withdraw their savings, in Shanghai alone this run on the banks had caused 10 qianzhuang to close.

The main narrative around the relationship between the qianzhuang and foreign banking companies historically propagated by Chinese historians such as Zhang Guohui paints the relationship as foreign banks exploiting the native Chinese banks paving the way for foreign inroads into dominating the Chinese economy.[8] In a 2005 article Hamashita Takeshi debunked this narrative by illustrating that the foreign banks which did business in China did not take the majority of the profits made by the qianzhuang and that most of the activity done by the qianzhuang did not involve any chop loans and this activity was even more marginal on the balance sheets of the foreign banks conducting business in China; in fact, at times, the qianzhuang (and other Chinese banks such as the Imperial Bank of China) would even lend money back to foreign banks which requested this on call.[8]

During the latter half of the 19th century Shanghai had large native Chinese banks which were credit institutions and smaller native Chinese banks that were non-credit institutions, these smaller banks were divided into 4 classes these classes were based on a kind of numeration following the first words of the Confucian classic literary text, the I Ching, these 4 classes were the yuan (元), heng (亨), li (利), and the zhen (貞). The yuan banks and the heng banks operated as assayers and as money-changers or tiaoda qianzhuang (挑打錢莊), while the li banks and the zhen banks operated exclusively as cash coin-changers or lingdui qianzhuang (零兌錢莊).[6]

In the year 1883 the tycoon Hu Xueyan from the province of Zhejiang, who had a business network which covered most of the southern regions of China, was forced to declare bankruptcy following a disastrous business decision. Hu Xueyan spent millions of taels to purchase raw silk to try to get a monopoly on the silk trade, unfortunately for Hu Xueyan, foreigners started boycotting him causing him to sell the silk at prices below the ones for acquisition bankrupting him in the process.[23] This whole ordeal caused Hu to become unable to pay the 560,000 taels of silver that his company owed to 40 different Shanghai qianzhuang. The default on these loans resulted in most of these Shanghai qianzhuang going bankrupt, furthermore hundreds of other Chinese companies were also folding due to an economic ripple effect as they now could no longer get the loans they needed to do business from these bankrupted outlets. The chain effect led to a major financial downturn in the economy of Shanghai. In the year 1876 there were a total of 105 registered qianzhuang in Shanghai but by 1883, the year of the crash, only 20 qianzhuang had survived in all of Shanghai.

It took well over a decade for the qianzhuang industry to restore itself following this debacle, but only 11 years later in 1894 the market was hit heavily by another crisis. During this time a large number of companies engaged in Qing China's lucrative opium business were quite willing to pay high interest rates for loans. In order to attract cash savings, some qianzhuang would sell zhuangpiao at high interest rates ranging from 2% to 20%. Some qianzhuang would even offer a staggering number of 50% interest rates on their zhuangpiao. This situation would face a quick downturn when in the year 1894 several qianzhuang started to fraudulently declare bankruptcy as a means to avoid paying out the promised interest rates on the zhuangpiao. This led to a total of 2,000,000 taels of silver in zhuangpiao being rendered without value, this event would cause many Chinese people to see the qianzhuang as disreputable and untrustworthy.

Around the year 1890 the larger Chinese banks in Shanghai had developed a form of clearance management known as the gongdan zhidu (公單制度) which occurred on a daily basis, during the gongdan zhidu the banks of Shanghai would meet in the afternoon in a huihua zonghui (匯劃總會, or clearing house) and would then proceed to clear their holdings of letters of exchange and banknotes, this allowed them to settle all the claims and liabilities of their accounts for that day.[6]

While both Mainland European and Japanese banks were latecomers into the Chinese market, these banks were also a lot more ready to engage the domestic Chinese sector. Kwan Man Bun showed how foreign banks such as the French (Saigon, French Indochina-based) Banque de l'Indochine, Russian Russo-Chinese Bank, and Japanese Yokohama Specie Bank were pivotal in helping Chinese salt merchants in Tianjin tide over their losses due to the Boxer Rebellion.[8][24]

There were large disparities between the structures of both Chinese qianzhuang banks and the overall Chinese banking sector and how foreign banks operated in China, this was partially due to the geographical distribution of the different kinds of banks. An advantage which Chinese banks like the qianzhuang had over foreign banks was the fact that they had leeway to popularise their banknotes in the vast Chinese hinterland that stretched far beyond the confines of the treaty ports, which the foreign banks were bound to. However, within the treaty ports of China, these foreign banking companies enjoyed extraterritoriality which, unlike the local qianzhuang, protected them from Chinese government intervention. But because they were bound to only Chinese treaty ports most foreign banks would not establish any branches in other Chinese cities, with the notable exception being the capital city of Beijing which was politically both high important and very sensitive.[8]

While the qianzhuang of Shanghai were a very successful story of the modernisation of the Chinese financial landscape, the tycoons who presided over the Shanghai qianzhuang exercised very little to no power in the vast Chinese hinterland and only dominated the banking sector of Eastern China, during the era the city of Tianjin ruled over the banking sector of Northern China, Guangzhou over Southern China, and Hankou over Central China. While Shanghai played an important role, the agricultural trade of China was still heavily dependent on the more traditional qianzhuang of elsewhere. Hankou being a hinterland city would be more affected by the multitudes of local constraints, despite these local constraints Hankou was the second largest business port in all of China behind Shanghai during this period being often called "the Chicago of China" while maintaining intimate ties with Shanghai.[7] The relationships between foreign banks in Shanghai and the Shanghai qianzhuang and the foreign banks in Hankou with the Hankou qianzhuang were largely analogous, but modern scholarly interests in the topic have largely focused on Shanghai. Like how the Shanghai qianzhuang were bound to the laws of their guild, the Hankou qianzhuang had a similar system in place.[7]

The disparities between the qianzhuang and the foreign banks in China may have also been derived from the overemphasis laid at banknote issuance as a definitive constituent of modern banking by Chinese reformers during the late-Qing dynasty period. These reformers were quick to point out how Qing China's institutional weakness was a reason why foreign banks were enabled to recoup profits from the issuance of fiat banknote in the treaty ports where they were allowed to operate. Foreign banks typically would fail to heed attendant reserve requirements customary in the Chinese banking sector, this was something that set them apart from traditional Chinese financial institutions such as the qianzhuang.[8] The reformers of the late-Qing dynasty era would plead to the Emperor to create government-run banks which would be able to counter foreign economic inroads into the Chinese economy. Despite seeking to modernise both the Chinese banking sector and economy, the arguments put forward by these reformers were not materially different from the arguments made by earlier Qing bureaucrats who had attempted to persuade the Manchu administration to overprint the failed Da-Qing Baochao and Hubu Guanpiao banknotes as panacea for the dynastic decline leading to the Xianfeng inflation. But as the monetary discourse had been altered so much during this period that while the reformers in the 1850s had been castigated for their suggestions, the reformers in the 1890s could make more daring propositions with impunity, such as proposing that the Chinese government should adopt the gold standard.[8][25][26][27]

_Bonistika.net_02.png.webp)

As the imperial government of the Qing dynasty was severely strained fiscally, they had to face the same dilemma as they had faced during the 1850s. This dilemma was how to retain their revenue without causing severe inflation which would provoke large scale resistance from the people, and without surrendering more central powers to banking and financial institutions. The government of the Qing dynasty during the 1890s and 1900s was often blighted by both indecision and contradictory policies that would obviate any lasting synergy between the imperial government and private financial and monetary spheres. By the 1850s, or possibly even earlier, this deficiency in centralised monetary policy had allowed privately funded British trading houses and Anglo-Indian financial institutions to take advantage of the situation and meant that they could thrive in the trading cities and ports in coastal China.[8][28]

In the summer of 1896, under request of Zhang Zhidong, the provincial government of Hubei created the Hupeh Provincial Bank (湖北官錢局, Hubei Guan-Qianju) in the city of Wuchang. The Hubei Guan-Qianju provincial bank established another branch office in the city of Hankou in January of the year 1897. Despite being established during the 1890s by a Chinese provincial government, it was not a modern-style bank but a province-owned qianzhuang.[7] Both the Wuchang and Hankou branches of the Hubei Guan-Qianju issued a series of banknotes known as the Hubei Guanpiao (湖北官票) which was denominated in both silver taels and strings of copper-alloy cash coins. While the local government started restricting the public issuing of zhuangpiao banknotes by qianzhuang, this new series of banknotes, which was under the aegis of Zhang's coin factory and provincial tax revenues, would circulate locally and had enjoyed a good reputation in its early years of their issuance, this fact ought to be accredited in part to Zhang and his policies. This changed however in the year 1926 when the issue of Hubei Guanpiao banknotes became erratic. Both the Wuchang and Hankou branches of the Hubei Guan-Qianju rushed into bankruptcy in 1927, this led to the establishment of another bank, the Hubei Bank.[7]

Zhang Zhidong may have opened a new chapter of the monetary history of China, but scholarly debates still question whether or not his actions were helpful in reviving China's aged monetary system. Yun Liu argues that Zhang's acts may have in fact contributed in making the system even more chaotic than it initially was, by introducing a provincial bank (or provincial qianzhuang in this case) he set precedent for other provinces to follow suit causing the central government of the Qing dynasty to lose even more control over the Chinese monetary system.[7] Zhang's actions were also detrimental to the success of the Hankou qianzhuang, in the year 1899 after reading a report that there were 103 qianzhuang in the city of Hankou, Zhang instructed his subordinates to reduce this number to "the ideal number" of 100 and that this number would have to be maintained forever. Zhang Zhidong also stated that the yearly flood relief donation collection from qianzhuang, which was 400 to 600 taels of silver for renewing members, and 1000 for newcomers, should continue. During this era there was rampant amounts of frauds and forgeries being reported, to address this Zhang simply ordered that the trade census be thorough and that more responsibilities should be assumed via a form of mutual governance by the trade conducted by the qianzhuang itself. However, his order did not perform well and didn't solve any of the reported issues.[7]

In the year 1908 a report by the local administration of Hankou noted that only a handful of qianzhuang fulfilled government set codes; a large number of them had not filed their registry for years. The administrative report advised that the local authorities should concede the registry fees furtively negotiated with qianzhuang, or otherwise simply resume with their current policy as it seemed a fine option to maintain a registration fee of 600 teals for renewals and 1000 for newcomers.[7] Despite facing a heavy burden of extortion by the municipal government, the Hankou qianzhuang were still capable of escaping bureaucratic domination and they played a very active role in daily local business and maintained a relative amount of their own autonomy during this period.[7]

It was not uncommon for qianzhuang to make loans which were worth several times the size of their actual capital. A qianzhuang which only had as little of 20,000 to 40,000 taels of silver in capital reserves would often make loans to lenders that numbered in multiples of hundreds of thousands of taels. In the year 1907 the Fukang Qianzhuang in Shanghai, which only haf 20,000 taels in paid-up capital had issued over 1,000,000 taels in loans.

Between the years 1907 and 1908 there was an abrupt debacle caused by the three largest Hankou qianzhuang with owners from Jiangxi, all these qianzhuang had an initial "Yi" (, "joy") in their brand names, caused a large local market crisis. The miserable cause célèbre of the triple Yi qianzhuang had to be settled via collective acts of all qianzhuang and piaohao members in the city of Hankou.[7] This meant that the trade was voluntarily halted for months. This led to several panicking merchants to commit suicide as a desperate last act in an attempt to salvage their names. Eventually further runs on the banks ended and the Hankou qianzhuang would halt issuing Zhiqian (制錢, "Standard cash coins") permanently. The Hankou qianzhuang with owners from Jiangxi lost their top place to qianzhuang with owners from Anhui, while the Hankou piaohao completely collapsed at Hankou in the year 1911.[7]

The qianzhuang business was dealt a heavy blow when in 1910 the rubber crisis happened. A large number of qianzhuang had made several large investments in rubber companies, at the time there was a general perception that these companies were very profitable. The shareholders of large qianzhuang like the Zhengyuan Qianzhuang, Zhaokang Qianzhuang, and the Qianyu Qianzhuang had invested all the money they had in the Shanghai stock market and even went so far to borrow money from foreign banks to invest into rubber stocks. Together these shareholders bought 13,000,000 taels of silver worth of rubber stocks. In the year 1910 the total number of investments made in rubber stock companies was as high as 60,000,000 taels of silver, consequently the Shanghai financial market suffered because there wasn't enough cash to make loans. As a result, many Shanghai qianzhuang started issuing loans using rubber company stocks as security.

Initially this proved to be a sound investment strategy as the price of rubber stocks hit a historical high in April 1910, but these stocks became almost worthless almost 3 months later in July of that same year. As a result, more than 100 people in the city of Shanghai had committed suicide because they had lost all of their savings in speculating in rubber stocks. By the end of the same year around 50 Shanghai qianzhuang, half of the officially registered Shanghai qianzhuang, were forced to close their doors because they were drowning in debt. The government of the Qing dynasty was forced to borrow money from the foreign banks to be able to bail out the Shanghai qianzhuang and introduced new regulations to make sure that the managere of qianzhuang weren't allowed to open other businesses or use the savings that were deposited at their bank for any other purposes. These newly introduced rules were made to ensure that a manager had to take full responsibility if a qianzhuang went bankrupt, and speculating in the stock market was outlawed for managers.

While the collapse of the Qing dynasty meant the end of the Shanxi banks in 1911, Shanghai's qianzhuang would continue to operate right up to the 1940s when the Japanese occupation disrupted their operations.[8][15][16]

Republic of China

The Wuchang Uprising of 1911 occurred right next to Hankou, but despite China transitioning from a monarchy into a republic, the newly formed Chinese republic inherited its passé dynasty with fairly limited changes. Very little improvements came to the monetary market of Hankou and the qianzhuang would remain to be de facto unregulated businesses. The status quo would remain largely the same during the early Republican years, but the system based on social ties started experiencing more dynamic changes.[7]

By February of the year 1912 only 24 qianzhuang remained in business in Shanghai.

In Hankou the qianzhuang were divided into four cliques which were based on their owner's native place or county of origins, these social ties in Chinese culture were linked together in a vague concept known as "Tongxiang" (which could be translated as "hometown-folk"). This division was seen as a source of both market stability and cohesiveness, in the city of Hankou they were known as "Bang" and had a suffix attached referring to their place of origin.[7] If a qianzhuang is facing a broken capital chain, with poor liquidity, or risks becoming stuck in a debt crisis, shareholders will take unlimited risk responsibility to ensure the interests of creditors with all their capital strength outside of the concerned qianzhuang. In fact, when necessary, many shareholders can also use their own commercial credit to mobilise capital from the clique or their social network to maintain the credit to keep their business afloat.

The "Bang" of Hankou during the early Republican era included:[7]

| Cliques (or "Bang") of the Hankou qianzhuang | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of the clique | Place of origins | Number of qianzhuang in this clique in 1921 | Number of qianzhuang in this clique in 1925 | Average capital in 1921 (in taels of silver) | Average capital in 1925 (in taels of silver) |

| Ben-Bang | Hubei province[lower-alpha 2] | 53 | 69 | 19,000 | 28,000 |

| Hui-Bang | Anhui province | 3 | 8 | 26,000 | 28,000 |

| Xi-Bang[lower-alpha 3] | Jiangxi province | 18 | 35 | 14,000 | 24,000 |

| Zhe-Bang[lower-alpha 4] | Zhejiang province | 18 | 17 | 38,000 | 70,000 |

In another survey of the qianzhuang of Hankou which was published in the year 1935 it confirmed that 1925 was an unprecedented year for the Hankou qianzhuang, the number of qianzhuang increased from 136, since the last survey, to 180.[7]

The first mention of the four clique division being used for the Hankou qianzhuang was in 1911 by the Japanese Consul-General in Hankou, Mizuno Yukiyoshi (also written as "Midzuno").[29] The Japanese were the first to utilise this clique system and it was later adopted by the Chinese themselves for record keeping. He recorded there to be 65 Ben-Bang, 26 Xi-Bang (9 from Ji’an and 17 from Nanchang), 6 Hui-Bang, 8 Shao-Bang, 16 small Qianpu and Yin-Lufang with no identifiable native-places; a total of 121 qianzhuang were counted by the Japanese Consul-General in Hankou.[7] Like the piaohao (Shanxi banks) of Hankou, the owners of the qianzhuang would usually prefer to employ people from their own hometown and other merchants who had ancestral lineages from the same regions.[7]

The top position of Hankou qianzhuang would be taken by the Zhe-Bang (Shao-Bang), this clique was also the largest clique of the Shanghai qianzhuang. The Zhe-Bang qianzhuang were the last to arrive but enjoyed the fastest growth, they gained the top position during the late 1930s and would remain the dominant clique of the Hankou qianzhuang until their abolition in 1952.[7]

While the term "Ben-Bang" was used to describe qianzhuang with native others, many "Ben-Bang" also had owners from provinces (outlanders) like Hunan or Sichuan who were rejected by other cliques. For this reason the Ben-Bang served exclusively as a balancing role. Officially the Ben-Bang had the highest number of qianzhuang business, staff employed, and capital, but in reality the Ben-Bang did not have a home-court advantage among the Hankou qianzhuang like the Zhe-Bang had among the Shanghai qianzhuang. One of the reasons why this might be is because the more "native" (benren) owners were very much identified to the municipal government, as the local authorities were concerned for their political potential they might have viewed these "native" qianzhuang as a threat to their political power and thus advertently depressed them into their non-dominant position.[7]

In 1918 a local police report in Hankou had counted 329 qianpu.[7] In the year 1919 the city of Hankou filed a registry census to Beiping, in the report the city counted there to be 69 qianzhuang which had an average capital ranging from 6000 yuan to 35000 yuan. The Hankou qianzhuang on average received deposits from 2000 yuan to 120,000 yuan, since the last official trade census they had raised their cash reserve from 300 yuan to 10,000 yuan.[7] The differences between the 1918 and 1919 reports could have arisen due to the fact that the majority of smaller private banks were only quasi-registered at the local authorities.[7] Later in 1923 the local government had counted 152 officially registered qianzhuang in the city of Hankou.[7]

During the May Thirtieth Incident of 1925 in Shanghai, the city of Hankou also became an important centre for Chinese anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism movements. The British concession in Hankou would be abolished due to the actions of the Chinese anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism movements. The events completely changed the political map of the Hankou qianzhuang and might have been a cause for the merger of the four cliques.[7]

During the Kuomintang (KMT) takeover of the Chinese government during the years 1926 and 1927, the Chinese money market crashed again, this crash severely affected the Hankou qianzhuang, by the year 1927 only 5 qianzhuang remained in business in all of Hankou. However, within a single year the Hankou qianzhuang would experience a swift recovery, during this short time frame the number of qianzhuang operating in Hankou would return to 140.[7]

Prior to the year 1935 the Republic of China had a limited free banking system. Throughout China there were privately owned banks, although in reality the largest Chinese-owned banking companies and basically all the foreign-owned banks that were operating in China were based in the city of Shanghai.[30] Some Chinese provincial governments had established their own provincial banks, which had existed since the late Qing dynasty period, but these local government banks had to maintain the same standards as privately owned banks in order to compete on the financial market.[30]

In the year 1927 the Kuomintang took over the Chinese government and slowly started taking steps to replace the Chinese free banking system with a more centralised banking system. Instead of immediately seizing all private banks they took slow steps aimed at gaining complete control over the Chinese currency by getting both the financial and political support of the largest banks in China by making these dependent on the Nationalist Chinese government. The final step in this process was to completely bring every bank in China under the control or influence of the Chinese government.[30]

The slow process of getting complete control over the Chinese banking system by the government started in 1927 when the leaders of Communist labour unions instigated violent labour strikes in the city of Shanghai, these strikes completely crippled the industry of Shanghai. Shanghainese bankers appealed to the Kuomintang to stop the strikes.[30] Chiang Kai-Shek saw these strikes as an opportunity to improve the financial standing of the new Chinese Nationalist government and he created a deal where he would take down the strikes in exchange for the bankers giving out loans for the newly established government. The banks of China calculated that a Communist Party victory would be less beneficial for them than a Kuomintang victory so they were eager to support the Kuomintang through issuing loans.[30] However, the Chinese government appeared to be a financial black hole and the heads of China's largest banks began to suspect that the Chinese Nationalist government wasn't able to pay back their debts, this was as the Chinese government continued to increase its debt without having any way of servicing it to those it owed.[30] This led to some bankers to stop giving out more loans to the Chinese Nationalist government, but as a response Chiang started treating these bankers the same as he had done his political adversaries and would imprison them or confiscate their property on the grounds that these bankers were being politically subversive.[30]

On November 3, 1935, the Chinese Nationalist government had issued the Currency Decree.[30] This decree came into effect on November 4, it stipulated that only banknotes issued by the three largest government-owned banks—the Bank of China (中國銀行), the Bank of Communications (交通銀行), and the Central Bank of China (中央銀行)—would be accepted as legal tender in China.[30] The banknotes that were issued by private banks, such as the zhuangpiao, were allowed to continue circulating on the Chinese market in fixed amounts, and later they were to be gradually phased out completely.[30] All private institutions and individuals who owned silver were ordered by the Chinese Nationalist government to exchange their silver for the new national currency within a period six months.[30]

In the city of Hankou modern banks had been rising steadily, but the relationship between these new players and the Hankou qianzhuang was amicable.[7] The Hankou qianzhuang guild encouraged collaboration between the modern banks and the qianzhuang and would not reject modern banks from its clearing-house in its process of exchange. This did not even change after the modern banks of Hankou had created their own clearing-house later.[7]

By the year 1945 only 88 qianzhuang were officially recorded in Hankou, by this time the old clique system had been replaced by a new system to categorise the qianzhuang based on their ownership, a diverse number of identities were used:[7]

| Social groups of the owners with a percentage of the total capital of all registered Hankou qianzhuang | |

|---|---|

| Social group | Percentage |

| Merchants | 40.18% |

| Native bankers | 30.07% |

| Industrialists | 8.07% |

| Senior managers | 6.15% |

| Modern bankers | 5.96% |

| Jewellery dealers | 4.91% |

| Compradors | 1.82% |

| Government officers | 1.45% |

| Pawn shop owners | 1.05% |

During this survey a total number of 679 owners registered. It appeared as if the division of Hankou qianzhuang which was based on the hometown of the owners was replaced by a system where the cliques were based on which qianzhuang had existed before World War II and which qianzhuang was established afterwards.[7] The clique of pre-war qianzhuang in Hankou had 31 affiliated members, while the clique of post-war qianzhuang counted 57 members, but the latter would only include 27 members following a series of mergers. In the year 1946 the number of Hankou qianzhuang would rise to 110, and a year later, in 1947, this number had risen to as much as 180.[7]

In 1947 the Shanghai qianzhuang guild invited the guilds from 8 major Chinese cities to form a national qianzhuang guild.[7]

In the year 1947, the Nanjing government had commenced closing down illegal qianzhuang in metropolitan areas all over China. This action had a negative impact on many qianzhuang and several Hankou qianzhuang started to attempt to lobby Nanjing to cease the new regulations, throughout China the new regulations were met with great resistance.[7] During the beginning of the year 1948 a new local regulatory body was set up to enforce the new regulations and codes set by Nanjing. But despite these measures the Nanjing government did not have the resources to enforce many of these measures as its position was gradually weakening in light of Communist advances during the Chinese civil war. In the entire city of Hankou only 60 qianzhuang were fortunate to receive government licenses, this process meant that 48 Hankou qianzhuang were officially ruled to close.[7]

In order to stay afloat many qianzhuang started engaging in double-entry bookkeeping in order to keep off extortions, while many would rush into speculative endeavors which meant that they would now find themselves into even greater financial risks.[7]

People's Republic of China

When the People's Liberation Army entered Hankou in early 1949 a total of 36 qianzhuang had remained in the city. Following the Communist takeover of Wuhan, the city's financial order was swiftly restored.[7] The measures taken by the Communists included the enforcement of official registry codes, setting a higher mandatory reserve and registry-capital, creating a standardised set of codes for both bookkeeping and issuing commercial loans, making market speculation illegal, unifying two draft exchanges of commercial banks and the Hankou qianzhuang, and heavily penalising those in the business of making forgeries.[7]

During this period the archives stated that 21 qianzhuang in Hankou applied to be officially registered and 18 qianzhuang were approved with 3 of them being rejected, these 3 qianzhuang would later apply for a business clearance which were all approved at the cost of being subject to meticulous monitoring by the Communist authorities.[7]

The Communists started introducing many Soviet-style reforms, but while many of the reforms affecting the ancien régime banks, including the qianzhuang, superficially resembled the reforms of the Soviet Union, the Chinese Communists would adopt a strategy which they dubbed "cultural positioning". This model would utilise traditional Chinese cultural influences in the process of implementing radical Socialist changes. During this transitional period the qianzhuang of China would maintain their strong traditional identity, but as qianzhuang were severely influenced by the political changes that affected them, many qianzhuang adopted a strategy of political compliance for their continued existence.[7] The Communist Party saw the qianzhuang in a very antagonistic light, this was for a myriad of reasons strongly related to their Confucian nature. The leaders of the Communist Party of China viewed the qianzhuang as being a part of the hated bourgeoisie and claimed that qianzhuang were anti-progressive, nationalistic, reactionary against the Socialist revolution, and that they were very politically unreliable. The Communist Party hoped to transform the qianzhuang to serve the proletariat instead of the bourgeoisie.[7] In reality, the political ambiguity of the qianzhuang were likely an obstacle in the eyes of those who wished to transform the Mainland Chinese economy into a state-controlled planned economy. But during the initial phase of the People's Republic of China the continued existence of the independent qianzhuang was tolerated.[7]

During the year 1950 the Hankou qianzhuang steadily experienced a recovery, the recovery of the qianzhuang was crucial for the economy of Hankou following the devastating hyperinflation that affected Mainland China during the aftermath of World War II and the retreat of the Nationalist Chinese government to Taiwan. The financial authority of Wuhan introduced more regulations and policies affecting the local qianzhuang.[7] The new Wuhan financial authority placed all banks, including qianzhuang, piaohao (Shanxi banks), and commercial banks, into a single category. The local government of Wuhan attempted to negotiate mandatory deposit reserve ratios for banks, valorise credit markets, and release tighter remittance restrictions on all banks to stimulate the ravaged economy.[7]

By the end of the year 1950 the Wuhan financial authority would place all qianzhuang and the sole remaining piaohao of Wuhan, most of which were located in former Hankou, into 3 bank unions, the banks were allowed to negotiate which union they would join.[7] 7 qianzhuang would form the first banking union, 5 Zhe-Bang qianzhuang and 1 piaohao formed the second banking union, and 5 qianzhuang formed the third banking union.[7]

In August of the year 1951 all of these banking unions were merged into a new bank named the United Commerce Bank of Wuhan (or Wuhan United Commerce Bank).[7] Not all banks joined as one Zhe-Bang qianzhuang, which was originally a member of the second banking union, had declined merging into it. As this Zhe-Bang qianzhuang had a sufficient number of its own capital to stay afloat it decided to successfully transform itself into a metal-nail factory in the area of former Hankou. But by 1952 this factory would face debts that were skyrocketing and closed its doors.[7] The United Commerce Bank of Wuhan would convert itself into an agricultural product transportation and trade business in September of the year 1952, from an ostensibly abysmal status with skyrocketing debts announced.[7]

qianzhuang disappeared almost inconspicuously in the year 1952. The Hankou archival evidences from the local sources indicate that their official dissolution been the result of political changes rather than from their inability to serve modern businesses or any form of resistance against ruling orders.[7]

During the 1990s the term qianzhuang would experience a revival in Mainland China, in this context qianzhuang refer to informal finance companies which operate within the boundaries of illegality and legality.[7] Like the earlier qianzhuang, the ones that emerged during the late 20th and early 21st centuries tended to be privately owned businesses, they have structures of partnership or sole-proprietorship, with assumingly unlimited liability, they also tend to be operated solely by privately financed credit, they egregiously rely on their owners’ social circles, are barely protected by the Chinese state or any of its laws, and are often accused of being loan-sharks or fronts for money-laundering operations.[7] The re-emergence of qianzhuang can help explain why the Chinese tend to offer resistance to the deregulation of its monetary system. Despite the authorities of the People's Republic of China distrusting the qianzhuang, their existence has become too ubiquitous to be trivialised.[7] Yun Liu states that in spite of all the large changes which affected the economy of the People's Republic of China since the 1950s, there is a déjà vu in how both the policymakers of the People's Republic of China and its business sector treat the qianzhuang.[7]

An example of how the modern day situation seems to mirror the 1950s is the fact that the local government of Wuhan merged dozens of smaller local credit companies, that experienced a wild growth during the 1990s, into a new bank named the Wuhan Urban Commercial Bank, 11 years after its creation the Wuhan Urban Commercial Bank was renamed to the "Hankou Bank" in June of the year 2008. This regional bank is incorporated with both public shares and with state-owned assets.[7] Yun Liu thinks that this rebranding might have been done to reflect a gesture of salutation to the Hankou qianzhuang in the local collective memories echoing Hankou as the city of commerce.[7]

Stringing of cash coins

Throughout Chinese history cash coins were put on strings in 10 groups of (supposedly) 100 cash coins each, these strings were separated by a knot between each group.[31] During the Qing dynasty period strings of cash coins rarely actually contained 1000 cash coins and usually had something like 950 or 980 or a similar quantity, these amounts were due to local preferences rather than being random in any form.[31] In the larger cities qianzhuang would make specific strings of cash coins for specific markets.[31] The qianzhuang existed because at the time there were many different kinds of cash coins circulating in China including old Chinese cash coins from previous dynasties (古錢), Korean cash coins, Japanese cash coins (倭錢), Vietnamese cash coins, large and small genuine Qing dynasty cash coins, and different kinds of counterfeits, such as illegally private minted cash coins.[31] Some of these strings would contain exclusively genuine Zhiqian, while other strings could contain between 30% and 50% of counterfeit and underweight cash coins.[31] The actual number of cash coins on a string and the percentage of counterfeits in a string was generally known to everyone who resided in that town by the type of knots that were used.[31] Each of these different kind of strings of cash coins fulfilled different functions.[31] For example, one string of cash coins was acceptable to be used in a local grain market while it would not be accepted at a meat market, while another type of string was able to be used in both markets while not to pay for taxes.[31] The qianzhuang sorted all cash coins into very specific categories, then they would make up appropriate kinds of strings that were intended for use in specific markets or to pay for taxes to the government.[31]

Scrip issued by qianzhuang

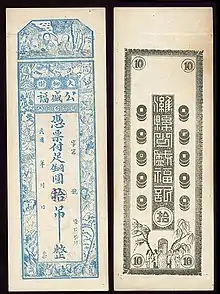

_Bonistika.net_01.png.webp)

Many qianzhuang issued their own scrip known as zhuangpiao (莊票) and (if denominated in silver) yinqianpiao (銀錢票, "silver money notes").[6] This scrip was also accepted by proximate shops but to cash these out would take around 10–15 days after it was given to the shop, this was because couriers would have to liaise with the issuing shop in order to verify their authenticity and rule out fraudulent zhuangpiao notes.[8]

When the Da-Qing Baochao (大清寶鈔) cash notes were suffering from inflation privately produced zhuangpiao cash notes were valued at double the nominal value of these government-issued cash notes, a number which increased to three and a half times as much before they were finally abolished in 1859.[32]

During this era Chinese banknotes had a lot of different currency units and almost every small region had their own regional currency with regional standards, Dr. Wen Pei Wei, in his 1914 book "The Currency Problem in China", stated "of a currency system it can be seen that China currently has none... No one single unit of currency in the Chinese system, if it can be called that, serves the function [of standard of value] for the country as a whole."[33] This was reflected in the zhuangpiao by the fact that many different currency units were traded based on the market rates and their relation to each other rather than using a standardised currency system as is customary in other countries.

During the late 19th century zhuangpiao banknotes were a common method of payment in the credit business of Shanghai and were both accepted by local and foreign banks.[6] The Qianzhuang would mobilise their domestic resources to an order of magnitude that would exceed the paid-up capital that they initially received several times over, this happened mostly through issuing banknotes and deposit receipts. British banks operating in China would often accept zhuangpiao as a security for the loans they gave out to qianzhuang. This makes it plausible that chop loans originated because of the widely used prevalence of zhuangpiao in China that British banks could simply not just to reject them when they were being offered to them by foreign merchants in China. During this era foreign banking companies tended to have an account at least one qianzhuang, since only the guilds operated by them could clear the large number zhuangpiao forms that were circulating in the city of Shanghai, this happened through a rather elaborate daily mechanism which was dubbed Huihua (非匯, "draft exchange").[8][34] The huihuazhuang credit banks of Shanghai enjoyed special privileges over the smaller banks such as the right to both issue and to accept yinpiao (銀票, "silver notes") denominated in silver taels and qianpiao (錢票, "cash notes") denominated in copper-alloy cash coins. The huihuazhuang credit banks also operated deposits and issued various types of paper money such as the discountable notes known as tiexian (貼現), furthermore they also issued their own banknotes (zhuangpiao) and bills of exchange (which were known as huapiao (匯票, "remittance notes").[6]

When the chop loan mechanism collapsed this severely affected the standing of zhuangpiao, much like all the other organic, private-order arrangements were badly hit, in a negative way on the monetary Chinese market. These private arrangements often concerned the individual intermediaries which were employed by foreign banks and financial institutions to guarantee Chinese liabilities like the zhuangpiao notes, the intermediary business rose up during the mid-19th century in Chinese treaty ports in response to both language barriers and information deficits facing foreigners who wished to do business in local Chinese markets. These intermediaries were commonly known as "compradors" to Westerners or maiban in Mandarin Chinese.[8][35] Compradors would personally guarantee the value of zhuangpiao issued by the qianzhuang and other Chinese liabilities before foreign institutions, but they did not actually have the leverage to guarantee any metallic money, such as the silver coins, disbursed by foreign institutions in the Chinese (monetary) marketplace. As China was suffering from a highly fractured monetary condition, this enabled the rise other highly specialised financial organisations precisely to that end, which were the gonguju and yinlu metal assayers.[8][36]

In the year 1933 the government of the Republic of China abolished the ancient silver-based currency unit, the tael and completely replaced it with the yuan in a process known as the fei liang gai yuan (廢兩改元). During this time the Republican government cleared all banknotes denominated in the ancient tael currency, making all bills which used this currency unit obsolete.[6]

The Hupeh Provincial Bank (湖北官錢局, Hubei Guan-Qianju), a provincial government-owned qianzhuang issued their own banknotes which were known as the Hubei Guanpiao (湖北官票), these banknotes were denominated in taels for silver and strings for copper-alloy cash coins.[7] The Hubei Guanpiao had magistrate seals affixed on them as endorsements, as the zhuangpiao by the local qianzhuang formerly practiced. In March of the year 1901 Zhang Zhidong commanded his subordinates to repudiate those magistrate seals on the Hubei Guanpiao banknotes that were issued as Zhang forthrightly explained to them that his foreign-made printing machines applied anti-forgery techniques, and that acquiescing seals would hamper circulating and competing banknotes issued by modern banks in China. The Hubei Guanpiao was abolished in 1927 with the bankruptcy of the Hubei Guan-Qianju. After the Hubei Guan-Qianju filed for bankruptcy in 1927 35 million strings in Hubei Guanpiao banknotes, which accounted for about half of the total of Hubei Guanpiao issued, were lost in the lengthy recall process by the defunct banks, as these banknotes had become completely worthless.[7]

Following the 1935 currency reform the government of the Republic of China introduced the fabi (法幣, "legal tender"), from November of the year 1935 to December 1936, the 3 officially sanctioned note-issuing banks issued the new paper currency, the fabi was completely detached from the silver standard. The Central Government of the Republic of China had enacted these currency reforms to limit currency issuance to three major government controlled banks: the Bank of China, Central Bank of China, Bank of Communications, and later the Farmers Bank of China. Chinese people were required by government mandate to hand in all of their current silver reserves in return for the newly introduced fabi, this was primarily done by the government in order to supply the silver that the Chinese government owed to the United States. The Chinese government and the central bank were careful to do a controlled release of about 2,000,000,000 yuan worth of new fabi banknotes, this was done in order to prevent inflation, and the government had taken many precautions to distribute these banknotes both gradually and fairly. In the first few months following the release of the fabi banknotes, the Chinese government did this to wait to see whether the Chinese public would place their trust in the new, unified Chinese currency.[37][38]

Classes of qianzhuang

The largest qianzhuang were first-class qianzhuang and tended to be mainly centered in large first-tier cities and major trading ports, first-class qianzhuang include the Shanghai qianzhuang, these qianzhuang tended to borrow money from larger financial institutions such as piaohao ("Shanxi banks") or from foreign banks. The general trend forms the pattern that the large financial institutions become financial wholesalers and qianzhuang becomes a retailer. Shanghai's qianzhuang place three positions of the "Eight Butlers" to do the job of creating relationships with other qianzhuang, piaohao, and modernised commercial banks, these staff members were the financial marketers, exchange managers, and interbank managers.

Second-class qianzhuang tended to be located in smaller cities and towns and had the habit of borrowing both cash and zhuangpiao from first-class qianzhuang such as those in Shanghai. Examples of second-class qianzhuang would be in second-tier places such as Jiujiang, Jiangxi, Wuhu, Anhui, and Zhenjiang, Jiangsu. The managers and street runners of smaller qianzhuang have an important task is to establish long-term human relations with big qianzhuang, piaohao, and modernised commercial banks, as well as to acknowledge the tightness degree of money and interest rate fluctuations which occur in the Chinese financial market, and they have to be ready to borrow more cash when the business of the qianzhuang is developing and when the reserves kept by the bank is insufficient to meet their business demands.

Third-class qianzhuang (or "Township qianzhuang") tend to borrow money from the second-class qianzhuang and they were found in places like Liyang, Jiangsu.

Contemporary reporting on and record keeping of the qianzhuang