Social network

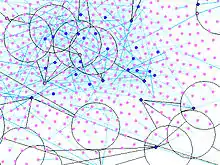

A social network is a social structure made up of a set of social actors (such as individuals or organizations), sets of dyadic ties, and other social interactions between actors. The social network perspective provides a set of methods for analyzing the structure of whole social entities as well as a variety of theories explaining the patterns observed in these structures.[1] The study of these structures uses social network analysis to identify local and global patterns, locate influential entities, and examine network dynamics.

| Part of a series on |

| Sociology |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

|

||||

Social networks and the analysis of them is an inherently interdisciplinary academic field which emerged from social psychology, sociology, statistics, and graph theory. Georg Simmel authored early structural theories in sociology emphasizing the dynamics of triads and "web of group affiliations".[2] Jacob Moreno is credited with developing the first sociograms in the 1930s to study interpersonal relationships. These approaches were mathematically formalized in the 1950s and theories and methods of social networks became pervasive in the social and behavioral sciences by the 1980s.[1][3] Social network analysis is now one of the major paradigms in contemporary sociology, and is also employed in a number of other social and formal sciences. Together with other complex networks, it forms part of the nascent field of network science.[4][5]

Overview

The social network is a theoretical construct useful in the social sciences to study relationships between individuals, groups, organizations, or even entire societies (social units, see differentiation). The term is used to describe a social structure determined by such interactions. The ties through which any given social unit connects represent the convergence of the various social contacts of that unit. This theoretical approach is, necessarily, relational. An axiom of the social network approach to understanding social interaction is that social phenomena should be primarily conceived and investigated through the properties of relations between and within units, instead of the properties of these units themselves. Thus, one common criticism of social network theory is that individual agency is often ignored[6] although this may not be the case in practice (see agent-based modeling). Precisely because many different types of relations, singular or in combination, form these network configurations, network analytics are useful to a broad range of research enterprises. In social science, these fields of study include, but are not limited to anthropology, biology, communication studies, economics, geography, information science, organizational studies, social psychology, sociology, and sociolinguistics.

History

In the late 1890s, both Émile Durkheim and Ferdinand Tönnies foreshadowed the idea of social networks in their theories and research of social groups. Tönnies argued that social groups can exist as personal and direct social ties that either link individuals who share values and belief (Gemeinschaft, German, commonly translated as "community") or impersonal, formal, and instrumental social links (Gesellschaft, German, commonly translated as "society").[7] Durkheim gave a non-individualistic explanation of social facts, arguing that social phenomena arise when interacting individuals constitute a reality that can no longer be accounted for in terms of the properties of individual actors.[8] Georg Simmel, writing at the turn of the twentieth century, pointed to the nature of networks and the effect of network size on interaction and examined the likelihood of interaction in loosely knit networks rather than groups.[9]

Major developments in the field can be seen in the 1930s by several groups in psychology, anthropology, and mathematics working independently.[6][10][11] In psychology, in the 1930s, Jacob L. Moreno began systematic recording and analysis of social interaction in small groups, especially classrooms and work groups (see sociometry). In anthropology, the foundation for social network theory is the theoretical and ethnographic work of Bronislaw Malinowski,[12] Alfred Radcliffe-Brown,[13][14] and Claude Lévi-Strauss.[15] A group of social anthropologists associated with Max Gluckman and the Manchester School, including John A. Barnes,[16] J. Clyde Mitchell and Elizabeth Bott Spillius,[17][18] often are credited with performing some of the first fieldwork from which network analyses were performed, investigating community networks in southern Africa, India and the United Kingdom.[6] Concomitantly, British anthropologist S. F. Nadel codified a theory of social structure that was influential in later network analysis.[19] In sociology, the early (1930s) work of Talcott Parsons set the stage for taking a relational approach to understanding social structure.[20][21] Later, drawing upon Parsons' theory, the work of sociologist Peter Blau provides a strong impetus for analyzing the relational ties of social units with his work on social exchange theory.[22][23][24]

By the 1970s, a growing number of scholars worked to combine the different tracks and traditions. One group consisted of sociologist Harrison White and his students at the Harvard University Department of Social Relations. Also independently active in the Harvard Social Relations department at the time were Charles Tilly, who focused on networks in political and community sociology and social movements, and Stanley Milgram, who developed the "six degrees of separation" thesis.[25] Mark Granovetter[26] and Barry Wellman[27] are among the former students of White who elaborated and championed the analysis of social networks.[26][28][29][30]

Beginning in the late 1990s, social network analysis experienced work by sociologists, political scientists, and physicists such as Duncan J. Watts, Albert-László Barabási, Peter Bearman, Nicholas A. Christakis, James H. Fowler, and others, developing and applying new models and methods to emerging data available about online social networks, as well as "digital traces" regarding face-to-face networks.

Levels of analysis

.svg.png.webp)

In general, social networks are self-organizing, emergent, and complex, such that a globally coherent pattern appears from the local interaction of the elements that make up the system.[32][33] These patterns become more apparent as network size increases. However, a global network analysis[34] of, for example, all interpersonal relationships in the world is not feasible and is likely to contain so much information as to be uninformative. Practical limitations of computing power, ethics and participant recruitment and payment also limit the scope of a social network analysis.[35][36] The nuances of a local system may be lost in a large network analysis, hence the quality of information may be more important than its scale for understanding network properties. Thus, social networks are analyzed at the scale relevant to the researcher's theoretical question. Although levels of analysis are not necessarily mutually exclusive, there are three general levels into which networks may fall: micro-level, meso-level, and macro-level.

Micro level

At the micro-level, social network research typically begins with an individual, snowballing as social relationships are traced, or may begin with a small group of individuals in a particular social context.

Dyadic level: A dyad is a social relationship between two individuals. Network research on dyads may concentrate on structure of the relationship (e.g. multiplexity, strength), social equality, and tendencies toward reciprocity/mutuality.

Triadic level: Add one individual to a dyad, and you have a triad. Research at this level may concentrate on factors such as balance and transitivity, as well as social equality and tendencies toward reciprocity/mutuality.[35] In the balance theory of Fritz Heider the triad is the key to social dynamics. The discord in a rivalrous love triangle is an example of an unbalanced triad, likely to change to a balanced triad by a change in one of the relations. The dynamics of social friendships in society has been modeled by balancing triads. The study is carried forward with the theory of signed graphs.

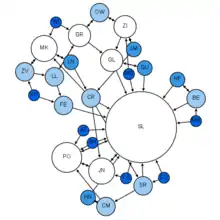

Actor level: The smallest unit of analysis in a social network is an individual in their social setting, i.e., an "actor" or "ego". Egonetwork analysis focuses on network characteristics such as size, relationship strength, density, centrality, prestige and roles such as isolates, liaisons, and bridges.[37] Such analyses, are most commonly used in the fields of psychology or social psychology, ethnographic kinship analysis or other genealogical studies of relationships between individuals.

Subset level: Subset levels of network research problems begin at the micro-level, but may cross over into the meso-level of analysis. Subset level research may focus on distance and reachability, cliques, cohesive subgroups, or other group actions or behavior.[38]

Meso level

In general, meso-level theories begin with a population size that falls between the micro- and macro-levels. However, meso-level may also refer to analyses that are specifically designed to reveal connections between micro- and macro-levels. Meso-level networks are low density and may exhibit causal processes distinct from interpersonal micro-level networks.[39]

Organizations: Formal organizations are social groups that distribute tasks for a collective goal.[40] Network research on organizations may focus on either intra-organizational or inter-organizational ties in terms of formal or informal relationships. Intra-organizational networks themselves often contain multiple levels of analysis, especially in larger organizations with multiple branches, franchises or semi-autonomous departments. In these cases, research is often conducted at a work group level and organization level, focusing on the interplay between the two structures.[40] Experiments with networked groups online have documented ways to optimize group-level coordination through diverse interventions, including the addition of autonomous agents to the groups.[41]

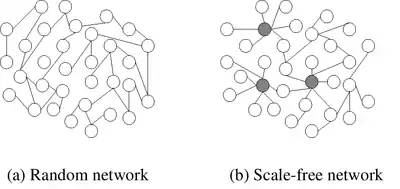

Randomly distributed networks: Exponential random graph models of social networks became state-of-the-art methods of social network analysis in the 1980s. This framework has the capacity to represent social-structural effects commonly observed in many human social networks, including general degree-based structural effects commonly observed in many human social networks as well as reciprocity and transitivity, and at the node-level, homophily and attribute-based activity and popularity effects, as derived from explicit hypotheses about dependencies among network ties. Parameters are given in terms of the prevalence of small subgraph configurations in the network and can be interpreted as describing the combinations of local social processes from which a given network emerges. These probability models for networks on a given set of actors allow generalization beyond the restrictive dyadic independence assumption of micro-networks, allowing models to be built from theoretical structural foundations of social behavior.[42]

Scale-free networks: A scale-free network is a network whose degree distribution follows a power law, at least asymptotically. In network theory a scale-free ideal network is a random network with a degree distribution that unravels the size distribution of social groups.[43] Specific characteristics of scale-free networks vary with the theories and analytical tools used to create them, however, in general, scale-free networks have some common characteristics. One notable characteristic in a scale-free network is the relative commonness of vertices with a degree that greatly exceeds the average. The highest-degree nodes are often called "hubs", and may serve specific purposes in their networks, although this depends greatly on the social context. Another general characteristic of scale-free networks is the clustering coefficient distribution, which decreases as the node degree increases. This distribution also follows a power law.[44] The Barabási model of network evolution shown above is an example of a scale-free network.

Macro level

Rather than tracing interpersonal interactions, macro-level analyses generally trace the outcomes of interactions, such as economic or other resource transfer interactions over a large population.

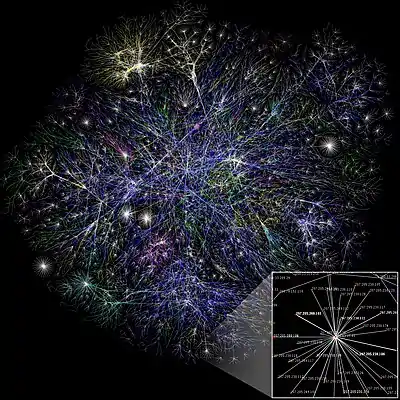

Large-scale networks: Large-scale network is a term somewhat synonymous with "macro-level" as used, primarily, in social and behavioral sciences, in economics. Originally, the term was used extensively in the computer sciences (see large-scale network mapping).

Complex networks: Most larger social networks display features of social complexity, which involves substantial non-trivial features of network topology, with patterns of complex connections between elements that are neither purely regular nor purely random (see, complexity science, dynamical system and chaos theory), as do biological, and technological networks. Such complex network features include a heavy tail in the degree distribution, a high clustering coefficient, assortativity or disassortativity among vertices, community structure (see stochastic block model), and hierarchical structure. In the case of agency-directed networks these features also include reciprocity, triad significance profile (TSP, see network motif), and other features. In contrast, many of the mathematical models of networks that have been studied in the past, such as lattices and random graphs, do not show these features.[45]

Theoretical links

Imported theories

Various theoretical frameworks have been imported for the use of social network analysis. The most prominent of these are Graph theory, Balance theory, Social comparison theory, and more recently, the Social identity approach.[46]

Indigenous theories

Few complete theories have been produced from social network analysis. Two that have are structural role theory and heterophily theory.

The basis of Heterophily Theory was the finding in one study that more numerous weak ties can be important in seeking information and innovation, as cliques have a tendency to have more homogeneous opinions as well as share many common traits. This homophilic tendency was the reason for the members of the cliques to be attracted together in the first place. However, being similar, each member of the clique would also know more or less what the other members knew. To find new information or insights, members of the clique will have to look beyond the clique to its other friends and acquaintances. This is what Granovetter called "the strength of weak ties".[47]

Structural holes

In the context of networks, social capital exists where people have an advantage because of their location in a network. Contacts in a network provide information, opportunities and perspectives that can be beneficial to the central player in the network. Most social structures tend to be characterized by dense clusters of strong connections.[48] Information within these clusters tends to be rather homogeneous and redundant. Non-redundant information is most often obtained through contacts in different clusters.[49] When two separate clusters possess non-redundant information, there is said to be a structural hole between them.[49] Thus, a network that bridges structural holes will provide network benefits that are in some degree additive, rather than overlapping. An ideal network structure has a vine and cluster structure, providing access to many different clusters and structural holes.[49]

Networks rich in structural holes are a form of social capital in that they offer information benefits. The main player in a network that bridges structural holes is able to access information from diverse sources and clusters.[49] For example, in business networks, this is beneficial to an individual's career because he is more likely to hear of job openings and opportunities if his network spans a wide range of contacts in different industries/sectors. This concept is similar to Mark Granovetter's theory of weak ties, which rests on the basis that having a broad range of contacts is most effective for job attainment.

Research clusters

Art Networks

Research has used network analysis to examine networks created when artists are exhibited together in museum exhibition. Such networks have been shown to affect an artist's recognition in history and historical narratives, even when controlling for individual accomplishments of the artist.[50][51] Other work examines how network grouping of artists can affect an individual artist's auction performance.[52] An artist's status has been shown to increase when associated with higher status networks, though this association has diminishing returns over an artist's career.

Communication

Communication Studies are often considered a part of both the social sciences and the humanities, drawing heavily on fields such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, information science, biology, political science, and economics as well as rhetoric, literary studies, and semiotics. Many communication concepts describe the transfer of information from one source to another, and can thus be conceived of in terms of a network.

Community

In J.A. Barnes' day, a "community" referred to a specific geographic location and studies of community ties had to do with who talked, associated, traded, and attended church with whom. Today, however, there are extended "online" communities developed through telecommunications devices and social network services. Such devices and services require extensive and ongoing maintenance and analysis, often using network science methods. Community development studies, today, also make extensive use of such methods.

Complex networks

Complex networks require methods specific to modelling and interpreting social complexity and complex adaptive systems, including techniques of dynamic network analysis. Mechanisms such as Dual-phase evolution explain how temporal changes in connectivity contribute to the formation of structure in social networks.

Criminal networks

In criminology and urban sociology, much attention has been paid to the social networks among criminal actors. For example, murders can be seen as a series of exchanges between gangs. Murders can be seen to diffuse outwards from a single source, because weaker gangs cannot afford to kill members of stronger gangs in retaliation, but must commit other violent acts to maintain their reputation for strength.[53]

Diffusion of innovations

Diffusion of ideas and innovations studies focus on the spread and use of ideas from one actor to another or one culture and another. This line of research seeks to explain why some become "early adopters" of ideas and innovations, and links social network structure with facilitating or impeding the spread of an innovation.

Demography

In demography, the study of social networks has led to new sampling methods for estimating and reaching populations that are hard to enumerate (for example, homeless people or intravenous drug users.) For example, respondent driven sampling is a network-based sampling technique that relies on respondents to a survey recommending further respondents.

Economic sociology

The field of sociology focuses almost entirely on networks of outcomes of social interactions. More narrowly, economic sociology considers behavioral interactions of individuals and groups through social capital and social "markets". Sociologists, such as Mark Granovetter, have developed core principles about the interactions of social structure, information, ability to punish or reward, and trust that frequently recur in their analyses of political, economic and other institutions. Granovetter examines how social structures and social networks can affect economic outcomes like hiring, price, productivity and innovation and describes sociologists' contributions to analyzing the impact of social structure and networks on the economy.[54]

Health care

Analysis of social networks is increasingly incorporated into health care analytics, not only in epidemiological studies but also in models of patient communication and education, disease prevention, mental health diagnosis and treatment, and in the study of health care organizations and systems.[55]

Human ecology

Human ecology is an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary study of the relationship between humans and their natural, social, and built environments. The scientific philosophy of human ecology has a diffuse history with connections to geography, sociology, psychology, anthropology, zoology, and natural ecology.[56][57]

Language and linguistics

Studies of language and linguistics, particularly evolutionary linguistics, focus on the development of linguistic forms and transfer of changes, sounds or words, from one language system to another through networks of social interaction. Social networks are also important in language shift, as groups of people add and/or abandon languages to their repertoire.

Literary networks

In the study of literary systems, network analysis has been applied by Anheier, Gerhards and Romo,[58] De Nooy,[59] and Senekal,[60] to study various aspects of how literature functions. The basic premise is that polysystem theory, which has been around since the writings of Even-Zohar, can be integrated with network theory and the relationships between different actors in the literary network, e.g. writers, critics, publishers, literary histories, etc., can be mapped using visualization from SNA.

Organizational studies

Research studies of formal or informal organization relationships, organizational communication, economics, economic sociology, and other resource transfers. Social networks have also been used to examine how organizations interact with each other, characterizing the many informal connections that link executives together, as well as associations and connections between individual employees at different organizations.[61] Many organizational social network studies focus on teams.[62] Within team network studies, research assesses, for example, the predictors and outcomes of centrality and power, density and centralization of team instrumental and expressive ties, and the role of between-team networks. Intra-organizational networks have been found to affect organizational commitment,[63] organizational identification,[37] interpersonal citizenship behaviour.[64]

Social capital

Social capital is a form of economic and cultural capital in which social networks are central, transactions are marked by reciprocity, trust, and cooperation, and market agents produce goods and services not mainly for themselves, but for a common good. Social capital is split into three dimensions: the structural, the relational and the cognitive dimension. The structural dimension describes how partners interact with each other and which specific partners meet in a social network. Also The structural dimension of social capital indicates the level of ties among organizations.[65] This dimension is highly connected to the relational dimension which refers to trustworthiness, norms, expectations and idenfications of the bonds between partners.The relational dimension explains the nature of these ties which is mainly illustrated by the level of trust accorded to the network of organizations.[65] The cognitive dimension analyses the extent to which organizations share common goals and objectives as a result of their ties and interactions.[65]

Social capital is a sociological concept about the value of social relations and the role of cooperation and confidence to achieve positive outcomes. The term refers to the value one can get from their social ties. For example, newly arrived immigrants can make use of their social ties to established migrants to acquire jobs they may otherwise have trouble getting (e.g., because of unfamiliarity with the local language). A positive relationship exists between social capital and the intensity of social network use.[66][67] In a dynamic framework, higher activity in a network feeds into higher social capital which itself encourages more activity.[68]

Advertising

This particular cluster focuses on brand-image and promotional strategy effectiveness, taking into account the impact of customer participation on sales and brand-image. This is gauged through techniques such as sentiment analysis which rely on mathematical areas of study such as data mining and analytics. This area of research produces vast numbers of commercial applications as the main goal of any study is to understand consumer behaviour and drive sales.

Network position and benefits

In many organizations, members tend to focus their activities inside their own groups, which stifles creativity and restricts opportunities. A player whose network bridges structural holes has an advantage in detecting and developing rewarding opportunities.[48] Such a player can mobilize social capital by acting as a "broker" of information between two clusters that otherwise would not have been in contact, thus providing access to new ideas, opinions and opportunities. British philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill, writes, "it is hardly possible to overrate the value ... of placing human beings in contact with persons dissimilar to themselves.... Such communication [is] one of the primary sources of progress."[69] Thus, a player with a network rich in structural holes can add value to an organization through new ideas and opportunities. This in turn, helps an individual's career development and advancement.

A social capital broker also reaps control benefits of being the facilitator of information flow between contacts. In the case of consulting firm Eden McCallum, the founders were able to advance their careers by bridging their connections with former big three consulting firm consultants and mid-size industry firms.[70] By bridging structural holes and mobilizing social capital, players can advance their careers by executing new opportunities between contacts.

There has been research that both substantiates and refutes the benefits of information brokerage. A study of high tech Chinese firms by Zhixing Xiao found that the control benefits of structural holes are "dissonant to the dominant firm-wide spirit of cooperation and the information benefits cannot materialize due to the communal sharing values" of such organizations.[71] However, this study only analyzed Chinese firms, which tend to have strong communal sharing values. Information and control benefits of structural holes are still valuable in firms that are not quite as inclusive and cooperative on the firm-wide level. In 2004, Ronald Burt studied 673 managers who ran the supply chain for one of America's largest electronics companies. He found that managers who often discussed issues with other groups were better paid, received more positive job evaluations and were more likely to be promoted.[48] Thus, bridging structural holes can be beneficial to an organization, and in turn, to an individual's career.

Social media

Computer networks combined with social networking software produces a new medium for social interaction.[72] A relationship over a computerized social networking service can be characterized by context, direction, and strength. The content of a relation refers to the resource that is exchanged. In a computer mediated communication context, social pairs exchange different kinds of information, including sending a data file or a computer program as well as providing emotional support or arranging a meeting. With the rise of electronic commerce, information exchanged may also correspond to exchanges of money, goods or services in the "real" world.[73] Social network analysis methods have become essential to examining these types of computer mediated communication.

In addition, the sheer size and the volatile nature of social media has given rise to new network metrics. A key concern with networks extracted from social media is the lack of robustness of network metrics given missing data.[74]

See also

- Bibliography of sociology

- Business networking

- Collective network

- International Network for Social Network Analysis

- Network society

- Network theory

- Network science

- Semiotics of social networking

- Scientific collaboration network

- Social network analysis

- Social network (sociolinguistics)

- Social networking service

- Social web

- Structural fold

References

- Wasserman, Stanley; Faust, Katherine (1994). "Social Network Analysis in the Social and Behavioral Sciences". Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN 9780521387071.

- Scott, W. Richard; Davis, Gerald F. (2003). "Networks In and Around Organizations". Organizations and Organizing. Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-195893-7.

- Freeman, Linton (2004). The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Empirical Press. ISBN 978-1-59457-714-7.

- Borgatti, Stephen P.; Mehra, Ajay; Brass, Daniel J.; Labianca, Giuseppe (2009). "Network Analysis in the Social Sciences". Science. 323 (5916): 892–895. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..892B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.536.5568. doi:10.1126/science.1165821. PMID 19213908. S2CID 522293.

- Easley, David; Kleinberg, Jon (2010). "Overview". Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-0-521-19533-1.

- Scott, John P. (2000). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Tönnies, Ferdinand (1887). Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, Leipzig: Fues's Verlag. (Translated, 1957 by Charles Price Loomis as Community and Society, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.)

- Durkheim, Emile (1893). De la division du travail social: étude sur l'organisation des sociétés supérieures, Paris: F. Alcan. (Translated, 1964, by Lewis A. Coser as The Division of Labor in Society, New York: Free Press.)

- Simmel, Georg (1908). Soziologie, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

- For a historical overview of the development of social network analysis, see: Carrington, Peter J.; Scott, John (2011). "Introduction". The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis. Sage. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-84787-395-8.

- See also the diagram in Scott, John (2000). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. Sage. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7619-6339-4.

- Malinowski, Bronislaw (1913). The Family Among the Australian Aborigines: A Sociological Study. London: University of London Press.

- Radcliffe-Brown, Alfred Reginald (1930) The social organization of Australian tribes. Sydney, Australia: University of Sydney Oceania monographs, No.1.

- Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (1940). "On social structure". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 70 (1): 1–12. doi:10.2307/2844197. JSTOR 2844197.

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude ([1947]1967). Les structures élémentaires de la parenté. Paris: La Haye, Mouton et Co. (Translated, 1969 by J. H. Bell, J. R. von Sturmer, and R. Needham, 1969, as The Elementary Structures of Kinship, Boston: Beacon Press.)

- Barnes, John (1954). "Class and Committees in a Norwegian Island Parish". Human Relations, (7): 39–58.

- Freeman, Linton C.; Wellman, Barry (1995). "A note on the ancestral Toronto home of social network analysis". Connections. 18 (2): 15–19.

- Savage, Mike (2008). "Elizabeth Bott and the formation of modern British sociology". The Sociological Review. 56 (4): 579–605. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954x.2008.00806.x. S2CID 145286556.

- Nadel, S. F. 1957. The Theory of Social Structure. London: Cohen and West.

- Parsons, Talcott ([1937] 1949). The Structure of Social Action: A Study in Social Theory with Special Reference to a Group of European Writers. New York: The Free Press.

- Parsons, Talcott (1951). The Social System. New York: The Free Press.

- Blau, Peter (1956). Bureaucracy in Modern Society. New York: Random House, Inc.

- Blau, Peter (1960). "A Theory of Social Integration". The American Journal of Sociology, (65)6: 545–556, (May).

- Blau, Peter (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life.

- Bernie Hogan. "The Networked Individual: A Profile of Barry Wellman".

- Granovetter, Mark (2007). "Introduction for the French Reader". Sociologica. 2: 1–8.

- Wellman, Barry (1988). "Structural analysis: From method and metaphor to theory and substance". pp. 19–61 in B. Wellman and S. D. Berkowitz (eds.) Social Structures: A Network Approach, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Mullins, Nicholas. Theories and Theory Groups in Contemporary American Sociology. New York: Harper and Row, 1973.

- Tilly, Charles, ed. An Urban World. Boston: Little Brown, 1974.

- Wellman, Barry. 1988. "Structural Analysis: From Method and Metaphor to Theory and Substance". pp. 19–61 in Social Structures: A Network Approach, edited by Barry Wellman and S. D. Berkowitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nagler, Jan; Anna Levina; Marc Timme (2011). "Impact of single links in competitive percolation". Nature Physics. 7 (3): 265–270. arXiv:1103.0922. Bibcode:2011NatPh...7..265N. doi:10.1038/nphys1860. S2CID 2809783.

- Newman, Mark, Albert-László Barabási and Duncan J. Watts (2006). The Structure and Dynamics of Networks (Princeton Studies in Complexity). Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Wellman, Barry (2008). "Review: The development of social network analysis: A study in the sociology of science". Contemporary Sociology. 37 (3): 221–222. doi:10.1177/009430610803700308. S2CID 140433919.

- Faust, Stanley Wasserman; Katherine (1998). Social network analysis : methods and applications (Reprint. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0521382694.

- Kadushin, C. (2012). Understanding social networks: Theories, concepts, and findings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Granovetter, M. (1976). "Network sampling: Some first steps". American Journal of Sociology. 81 (6): 1287–1303. doi:10.1086/226224. S2CID 40359730.

- Jones, C.; Volpe, E.H. (2011). "Organizational identification: Extending our understanding of social identities through social networks". Journal of Organizational Behavior. 32 (3): 413–434. doi:10.1002/job.694.

- de Nooy, Wouter (2012). "Social Network Analysis, Graph Theoretical Approaches to". "Graph Theoretical Approaches to Social Network Analysis". in Computational Complexity: Theory, Techniques, and Applications (Robert A. Meyers, ed.). Springer. pp. 2864–2877. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-1800-9_176. ISBN 978-1-4614-1800-9.

- Hedström, Peter; Sandell, Rickard; Stern, Charlotta (2000). "Mesolevel Networks and the Diffusion of Social Movements: The Case of the Swedish Social Democratic Party" (PDF). American Journal of Sociology. 106 (1): 145–172. doi:10.1086/303109. S2CID 3609428.

- Riketta, M.; Nienber, S. (2007). "Multiple identities and work motivation: The role of perceived compatibility between nested organizational units". British Journal of Management. 18: S61–77. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00526.x. S2CID 144857162.

- Shirado, Hirokazu; Christakis, Nicholas A (2017). "Locally noisy autonomous agents improve global human coordination in network experiments". Nature. 545 (7654): 370–374. Bibcode:2017Natur.545..370S. doi:10.1038/nature22332. PMC 5912653. PMID 28516927.

- Cranmer, Skyler J.; Desmarais, Bruce A. (2011). "Inferential Network Analysis with Exponential Random Graph Models". Political Analysis. 19 (1): 66–86. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.623.751. doi:10.1093/pan/mpq037.

- Moreira, André A.; Demétrius R. Paula; Raimundo N. Costa Filho; José S. Andrade, Jr. (2006). "Competitive cluster growth in complex networks". Physical Review E. 73 (6): 065101. arXiv:cond-mat/0603272. Bibcode:2006PhRvE..73f5101M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.73.065101. PMID 16906890. S2CID 45651735.

- Barabási, Albert-László (2003). Linked: how everything is connected to everything else and what it means for business, science, and everyday life. New York: Plum.

- Strogatz, Steven H. (2001). "Exploring complex networks". Nature. 410 (6825): 268–276. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..268S. doi:10.1038/35065725. PMID 11258382.

- Kilduff, M.; Tsai, W. (2003). Social networks and organisations. Sage Publications.

- Granovetter, M. (1973). "The strength of weak ties". American Journal of Sociology. 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469. S2CID 59578641.

- Burt, Ronald (2004). "Structural Holes and Good Ideas". American Journal of Sociology. 110 (2): 349–399. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.388.2251. doi:10.1086/421787. S2CID 2152743.

- Burt, Ronald (1992). Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- "Historic networks and commemoration: Connections created through museum exhibitions". Poetics. 81: 101446. 2020-08-01. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101446. ISSN 0304-422X.

- Braden, L. E. A. (2021-01-01). "Networks Created Within Exhibition: The Curators' Effect on Historical Recognition". American Behavioral Scientist. 65 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1177/0002764218800145. ISSN 0002-7642.

- Braden, L. E. A.; Teekens, Thomas (September 2019). "Reputation, Status Networks, and the Art Market". Arts. 8 (3): 81. doi:10.3390/arts8030081.

- Papachristos, Andrew (2009). "Murder by Structure: Dominance Relations and the Social Structure of Gang Homicide" (PDF). American Journal of Sociology. 115 (1): 74–128. doi:10.2139/ssrn.855304. PMID 19852186. S2CID 24605697. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- Granovetter, Mark (2005). "The Impact of Social Structure on Economic Outcomes". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 19 (1): 33–50. doi:10.1257/0895330053147958. JSTOR 4134991.

- Levy, Judith and Bernice Pescosolido (2002). Social Networks and Health. Boston, MA: JAI Press.

- Crona, Beatrice and Klaus Hubacek (eds.) (2010). "Special Issue: Social network analysis in natural resource governance". Ecology and Society, 48.

- Ernstson, Henrich (2010). "Reading list: Using social network analysis (SNA) in social-ecological studies". Resilience Science

- Anheier, H. K.; Romo, F. P. (1995). "Forms of capital and social structure of fields: examining Bourdieu's social topography". American Journal of Sociology. 100 (4): 859–903. doi:10.1086/230603. S2CID 143587142.

- De Nooy, W (2003). "Fields and networks: Correspondence analysis and social network analysis in the framework of Field Theory". Poetics. 31 (5–6): 305–327. doi:10.1016/S0304-422X(03)00035-4.

- Senekal, B. A. (2012). "Die Afrikaanse literêre sisteem: ʼn Eksperimentele benadering met behulp van Sosiale-netwerk-analise (SNA)". LitNet Akademies. 9: 3.

- Podolny, J. M.; Baron, J. N. (1997). "Resources and relationships: Social networks and mobility in the workplace". American Sociological Review. 62 (5): 673–693. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.114.6822. doi:10.2307/2657354. JSTOR 2657354.

- Park, Semin; Grosser, Travis J.; Roebuck, Adam A.; Mathieu, John E. (3 February 2020). "Understanding Work Teams From a Network Perspective: A Review and Future Research Directions". Journal of Management. 46 (6): 1002–1028. doi:10.1177/0149206320901573.

- Lee, J.; Kim, S. (2011). "Exploring the role of social networks in affective organizational commitment: Network centrality, strength of ties, and structural holes". The American Review of Public Administration. 41 (2): 205–223. doi:10.1177/0275074010373803. S2CID 145641976.

- Bowler, W. M.; Brass, D. J. (2011). "Relational correlates of interpersonal citizenship behaviour: A social network perspective". Journal of Applied Psychology. 91 (1): 70–82. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.516.8746. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.70. PMID 16435939.

- (Claridge, 2018).

- Sebastián, Valenzuela; Namsu Park; Kerk F. Kee (2009). "Is There Social Capital in a Social Network Site? Facebook Use and College Students' Life Satisfaction, Trust, and Participation". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 14 (4): 875–901. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01474.x.

- Wang, Hua & Barry Wellman (2010). "Social Connectivity in America: Changes in Adult Friendship Network Size from 2002 to 2007". American Behavioral Scientist. 53 (8): 1148–1169. doi:10.1177/0002764209356247. S2CID 144525876.

- Gaudeul, Alexia; Giannetti, Caterina (2013). "The role of reciprocation in social network formation, with an application to LiveJournal". Social Networks. 35 (3): 317–330. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2013.03.003. ISSN 0378-8733.

- Mill, John (1909). Principles of Political Economy. Library of Economics and Liberty: William J Ashley.

- Gardner, Heidi; Eccles, Robert (2011). "Eden McCallum: A Network Based Consulting Firm". Harvard Business School Review.

- Xiao, Zhixing; Tsui, Anne (2007). "When Brokers May Not Work: The Cultural Contingency of Social Capital in Chinese High-tech Firms". Administrative Science Quarterly.

- Amichai-Hamburger, Yair; Hayat, Tsahi (2017). The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0170. ISBN 9781118783764.

- Garton, Laura; Haythornthwaite, Caroline; Wellman, Barry (23 June 2006). "Studying Online Social Networks". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 3 (1): 0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00062.x.

- Wei, Wei; Joseph, Kenneth; Liu, Huan; Carley, Kathleen M. (2016). "Exploring Characteristics of Suspended Users and Network Stability on Twitter". Social Network Analysis and Mining. 6: 51. doi:10.1007/s13278-016-0358-5. S2CID 18520393.

Further reading

- Aneja, Nagender; Gambhir, Sapna (August 2013). "Ad-hoc Social Network: A Comprehensive Survey" (PDF). International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research. 4 (8): 156–160. ISSN 2229-5518.

- Barabási, Albert-László (2003). Linked: How Everything Is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life. Plum. ISBN 978-0-452-28439-5.

- Barnett, George A. (2011). Encyclopedia of Social Networks. Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-7911-5.

- Estrada, E (2011). The Structure of Complex Networks: Theory and Applications. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-59175-6.

- Ferguson, Niall (2018). The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, from the Freemasons to Facebook. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0735222915.

- Freeman, Linton C. (2004). The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Empirical Press. ISBN 978-1-59457-714-7.

- Kadushin, Charles (2012). Understanding Social Networks: Theories, Concepts, and Findings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537946-4.

- Mauro, Rios; Petrella, Carlos (2014). La Quimera de las Redes Sociales [The Chimera of Social Networks] (in Spanish). Bubok España. ISBN 978-9974-99-637-3.

- Rainie, Lee; Wellman, Barry (2012). Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262017190.

- Scott, John (1991). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. Sage. ISBN 978-0-7619-6338-7.

- Wasserman, Stanley; Faust, Katherine (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38269-4.

- Wellman, Barry; Berkowitz, S. D. (1988). Social Structures: A Network Approach. Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24441-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Social networks. |

Organizations

Peer-reviewed journals

- Social Networks

- Network Science

- Journal of Social Structure

- Journal of Mathematical Sociology

- Social Network Analysis and Mining (SNAM)

- "INSNA - Connections Journal". Connections Bulletin of the International Network for Social Network Analysis. Toronto: International Network for Social Network Analysis. ISSN 0226-1766. Archived from the original on 2013-07-18.

Textbooks and educational resources

- Networks, Crowds, and Markets (2010) by D. Easley & J. Kleinberg

- Introduction to Social Networks Methods (2005) by R. Hanneman & M. Riddle

- Social Network Analysis Instructional Web Site by S. Borgatti

- Guide for virtual social networks for public administrations (2015) by Mauro D. Ríos (in Spanish)