Racial sexual preference

Racial sexual preference is the preference for certain races in a sexual context.

While discrimination among partners based on perceived racial identity has been asserted by some to be a form of racism, it is generally considered a matter of personal preference.[1]

Attitudes towards interracial relationships

United States before Civil Rights Era

After the abolition of slavery in 1865, white Americans showed an increasing fear of racial mixture.[2] The remnants of the racial divide became stronger post-slavery as the concept of whiteness developed. There was a widely held belief that uncontrollable lust threatens the purity of the nation. This increased white anxiety about interracial sex, and has been described through Montesquieu's climatic theory in his book the Spirit of the Laws, which explains how people from different climates have different temperaments, "The inhabitants of warm countries are, like old men, timorous; the people in cold countries are, like young men, brave."[3] At the time, black women held the Jezebel stereotype, which claimed black women often initiated sex outside of marriage and were generally sexually promiscuous.[4] This idea stemmed from the first encounters between European men and African women. As the men were not used to the extremely hot climate they misinterpreted the women's lack of clothing for vulgarity.[5] Similarly, black men were stereotyped for having a specific lust for white women. This created tension, implying that white men were having sex with black women because they were more lustful, and in turn black men would lust after white women in the same way.

There are a few potential reasons as to why such strong ideas on interracial sex developed. The Reconstruction Era following the Civil War started to disassemble traditional aspects of Southern society. The Southerners who were used to being dominant were now no longer legally allowed to run their farms using slavery.[6] Many whites struggled with this reformation and attempted to find loopholes to continue the exploitation of black labor. Additionally, the white Democrats were not pleased with the outcome and felt a sense of inadequacy among white men. This radical reconstruction of the South was deeply unpopular and slowly unraveled leading to the introduction of the Jim Crow laws.[7] There was an increase in the sense of white dominance and sexual racism among the Southern people.

There were general heightened tensions following the end of the civil war in 1865, and this increased the sexual anxiety in the population. Races did not want to mix; white people felt dispossessed and wanted to take back control. The Ku Klux Klan then formed in 1867, which led to violence and terrorism targeting the black population.[8] There was a rise in lynch mob violence wherein many black men were accused of rape. This was not just senseless violence, but an attempt to preserve 'whiteness' and prevent racial blur; some racist whites wanted to continue a racial separation and make sure there was no interracial sexual activity. For example, mixed race couples that chose to live together were sought out and lynched by the KKK. The famous case of Emmett Till who was lynched at the age of fourteen under the belief he whistling at a white woman, when in actuality he was whistling for his own purposes, shows the extent of the violence taken against black people who flirted with white people.[9] When the Jim Crow laws were eventually overturned, it took years for the court to resolve the numerous acts of discrimination.

Challenges to attitudes

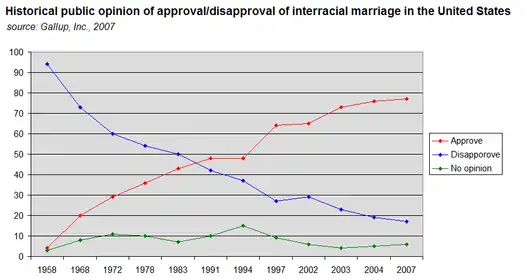

Sexual racism is presumed to exist in all sexual communities across the globe. The prevalence of interracial couples may demonstrate how attitudes have changed in the last 50 years.[10] A case that has perhaps received heightened publicity is that of Mildred and Richard Loving. The couple lived in Virginia yet had to marry outside the state due to the anti-miscegenation laws present in nearly half of the US states in 1958. Once married, the pair returned to Virginia, and were both arrested in their home for the infringement of the Racial Integrity Act, and each sentenced to a year in prison.[11]

Around a similar time, the controversy involving Seretse and Ruth Khama broke out. Seretse was the chief of an eminent Botswanan tribe, and Ruth a British student. The pair married in 1948 but experienced frequent hardships from the onset of the relationship, including Seretse's removal from his tribal responsibilities as chief in Bechuanaland. For nearly 10 years, Seretse and Ruth lived as exiles in Britain, as the government refused to allow Seretse to return to Bechuanaland. Once the couple were allowed to return to Bechuanaland in 1956, they became prominent campaigners for social equality, contributing to Seretse's election as president of the independent Botswana in 1966. Later, they continued campaigning for the legalization of interracial marriage around the globe.[12]

More recent examples portray the increasingly accepting attitudes of the majority to interracial relationships and marriage. In 1999, Jeb Bush was elected as Governor of Florida, accompanied by his wife, Columba, a Mexican woman he met in León who did not speak English when they met. They were one of the first interracial couples to stand in power side by side. Other prominent interracial couples in American politics are Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell and former Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao, as well as New York City mayor Bill de Blasio and his wife Chirlane McCray. The political success of these couples is seen by some to demonstrate that the attitudes of the world to interracial marriage are much more positive and optimistic than in previous decades.[13] Across much of the world, it is ever increasingly the situation that interracial couples can live, marry and have children without prosecution that was previously rife, due to major changes in law along with reductions in discriminatory attitudes.

Sexual preferences

In a study by Callander, Newman, and Holts, researchers found that racial preferences in one's own dating life were generally tolerated, with many participants feeling that racial preference was not racism.[1] They quoted Watts from the Huffington Post, who argued that sexual attraction and racism are not the same:

Just because someone isn't sexually attracted to someone of Asian origin does not mean they wouldn't want to work, live next to, or socialize with him or her, or that they believe they are somehow naturally superior to them.

— as cited in Callander, Newman, & Holts, 2015, p. 1992[14]

This suggests that people find it possible to view larger systemic racial preference as problematic, while viewing racial preferences in romantic or sexual personal relationships as not problematic. Researchers noted that calling racial preferences in one's own dating life "racist" is not a commonly accepted view.[1]

Online dating

In the last 15 years, online dating has overtaken previously preferred methods of meeting with potential partners, surpassing both the occupational setting and area of residence as chosen locations. This spike is consistent with an increase in access to the internet in homes across the globe, in addition to the number of dating sites available to individuals differing in age, gender, race, sexual orientation and ethnic background.[15] Partner race is the most highly selected preference chosen by users when creating their online profiles, ahead of both educational and religious characteristics.[16] Research has indicated a progressive acceptance of interracial relationships by white individuals.[17] The majority of white Americans are not against interracial relationships and marriage,[18] though these beliefs do not imply that the person in question will pursue an interracial marriage themselves. Currently, fewer than 5% of white Americans wed outside their own race;[19] indeed, less than 46% of white Americans are willing to date an individual of any other race.[20] Overall, African Americans appear to be the most open to interracial relationships,[21] yet are the least preferred partner by other racial groups.[20] However, regardless of stated preferences, racial discrimination still occurs in online dating.[16]

Each group significantly prefers to date intra-racially. Beyond this, in the online dating world, preferences appear to follow a racial hierarchy.[22] White Americans are the least open to interracial dating, and select preferences in the order of Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans and then African American individuals last at 60.5%, 58.5% and 49.4% respectively.[21] African American preferences follow a similar pattern, with the most preferred partner belonging to the Hispanic group (61%), followed by white individuals (59.6%) and then Asian Americans (43.5%). Both Hispanic and Asian Americans prefer to date a white individual (80.3% and 87.3%, respectively), and both are least willing to date African Americans (56.5% and 69.5%).[20] In all significant cases, Hispanic Americans are preferred to Asian Americans, and Asian Americans are significantly preferred over African Americans.[21] Hispanic Americans are less likely to be excluded in online dating partner preferences by whites seeking a partner, as Latinos are often viewed as an ethnic group that is increasingly assimilating more into white American culture.[23]

Another aspect of racial preferences is that that women of any race are significantly less likely to date inter-racially than a male of any race.[24] Specifically, Asian men and black men and women face more obstacles to acceptance online.[25] White women are the most likely to only date their own race, with Asian and black men being the most rejected groups by them.[26] The rejection of Asian men was asserted by one author to be due to a hypothetical effeminate portrayal in media.[27][28][29] The preference for men of other races remains present even when considering high-earning Asian men with an advanced educational background.[21][30][31] Increased education does however influence choices in the other direction, such that a higher level of schooling is associated with more optimistic feelings towards interracial relationships.[32] White men are most likely to exclude black women, as opposed to women of another race. High levels of previous exposure to a variety of racial groups is correlated with decreased racial preferences.[33] Racial preferences in dating are also influenced by the area of residence. Those residing in the south-eastern regions in American states are less likely to have been in an interracial relationship and are less likely to interracially date in the future.[34] People who engaged in regular religious customs at age 12 are also less likely to interracially date. Moreover, those from a Jewish background are significantly more likely to enter an interracial relationship than those from a Protestant background.[34]

A 2015 study of interracial online dating amongst multiple European countries, analyzing the dating preferences of Europeans, Arabs, Africans, Asians and Hispanics, found that in aggregate all races ranked Europeans as most preferred, followed by Hispanics and Asians as intermediately preferable, with Africans and Arabs the least preferred. Country-specific results were more variable, with countries with more non-Europeans showing more openness for Europeans to engage in interracial dating, while those with tensions between racial groups (such as in cases where tensions existed between Europeans and Arabs due to the recent influx of refugees) showed a marked decrease in preference for interracial dating between those two groups. The researchers noted that Arabs tended to have higher same-race preferences in countries with higher Arabic populations, possibly due to stricter religious norms on marriage amongst Muslims. The researchers did note a limitation of the study was selection bias, as the data gathered may have disproportionately drawn from people already inclined to engage in interracial dating.[33]

Currently, there are websites specifically targeted to different demographic preferences, such that singles can sign up online and focus on one particular partner quality, such as race, religious beliefs or ethnicity. In addition to this, there are online dating services that target race-specific partner choices, and a selection of pages dedicated to interracial dating that allow users to select partners based on age, gender and particularly race. Online dating services experience controversy in this context as debate is cast over whether statements such as "no Asians" or "not attracted to Asians" in user profiles are racist or merely signify individual preferences.[1]

Non-white ethnic minorities who feel they lack dating prospects as a result of their race, sometimes refer to themselves as ethnicels,[35] a term related to incel. Racial preferences can sometimes considered as a subset of lookism.[36]

LGBT community

It is the perception of one author that Asian men are often represented in media, both mainstream and LGBT, as being feminized or desexualized.[37] The gay Asian-Canadian author Richard Fung has written that while black men are portrayed as hypersexualized, gay Asian men are portrayed as being undersexed.[38] According to Fung, gay Asian men tend to ignore or display displeasure with races such as Arabs, blacks, and other Asians but seemingly give sexual acceptance and approval to gay white men. However, white gay men are more frequently than other racial groups to state "No Asians" when seeking partners.[39]

Asian American women also report similar discrimination in lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB) communities. According to a study by Sung, Szymanski, and Henrichs-Beck (2015), Asian American participants who identified as lesbian or bisexual often reported invisibility, stereotyping, and fetishism in LGB circles and the larger U.S. culture.[40]

Racial preferences are also prevalent in gay online dating. Phua and Kaufman (2003) noted that men seeking men online were more likely than men seeking women to look at racial traits.[41]

In a qualitative study conducted by Paul, Ayala, and Choi (2010) with Asian and Pacific Islanders (API), Latino, and African American men seeking men, participants interviewed endorsed racial preference as a common criterion in online dating partner selection.[42]

Racial bias

A 2015 study on sexual racism among gay and bisexual men found a strong correlation between test subjects' racist attitudes and their stated racial preferences.[43]

Philosopher Amia Srinivasan argued for racialized origins of Western beauty standards in her 2018 essay "Does anyone have the right to sex?", and stated that racial bias can shape sexual desire.[44]

Fetishisation

Sexual racism can manifest in the form of the hypersexualisation of specific ethnic groups. Freudians theorize that, in sexual fetishism, people of one race can form sexual fixations towards individuals of a separate generalised racial group. This collective stereotype is established through the perception that an individual's sexual appeal derives entirely from their race, and is therefore subject to the prejudices that follow.

Racial fetishism as a culture is often perceived, in this context, as an act or belief motivated by sexual racism. The objectification and reductionist perception of different races, for example, East Asian women, or African American men, relies greatly on their portrayal in forms of media that depict them as sexual objects ─ especially pornography.[45]

The effects of racial fetishism as a form of sexual racism are discussed in research conducted by Plummer.[46] Plummer used qualitative interviews within given focus groups, and found that specific social locations came up as areas in which sexual racism commonly manifests. These mentioned social locations included pornographic media, gay clubs and bars, casual sex encounters as well as romantic relationships. This high prevalence was recorded within Plummer's research to be consequently related to the recorded lower self-esteem, internalised sexual racism, and increased psychological distress in participants of color. People subject to this form of racial discernment are targeted in a manner well put by Hook.[47]

See also

References

- Callander, Denton; Newman, Christy E.; Holt, Martin (1 October 2015). "Is Sexual Racism Really Racism? Distinguishing Attitudes Toward Sexual Racism and Generic Racism Among Gay and Bisexual white Men". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 44 (7): 1991–2000. doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0487-3. ISSN 1573-2800. PMID 26149367. S2CID 7507490.

- Yancey, George (15 March 2019). "Experiencing Racism: Differences in the Experiences of Whites Married to Blacks and Non-Black Racial Minorities". Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 38 (2): 197–213. doi:10.3138/jcfs.38.2.197.

- De Montesquieu, C. (1989). Montesquieu: The Spirit of the Laws. Cambridge University Press.

- West, Carolyn M. (1995). "Mammy, Sapphire, and Jezebel: Historical images of Black women and their implications for psychotherapy". Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 32 (3): 458–466. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.32.3.458. ISSN 1939-1536.

- White, D. B. (1999). Ar'n't I a Woman. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Foner, E. and Mahoney O. (2003). America's Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War.

- Kousser, J. M. (2003). Jim Crow Laws. Dictionary of American History, 4, 479-480.

- Wade, W. C. (1998). The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Whitfield, S. J. (1991). A death in the delta: The story of Emmett Till. JHU Press.

- Mendelsohn, Gerald A.; Shaw Taylor, Lindsay; Fiore, Andrew T.; Cheshire, Coye (January 2014). "Black/White dating online: Interracial courtship in the 21st century". Psychology of Popular Media Culture. 3 (1): 2–18. doi:10.1037/a0035357. ISSN 2160-4142. S2CID 54038867.

- Moran, R. F. (2007). Loving and the Legacy of Unintended Consequences. Wis. L. Rev, 239, 240-281.

- Parsons, Neil (1 November 1993). "The impact of Seretse Khama on British public opinion 1948–56 and 1978". Immigrants & Minorities. 12 (3): 195–219. doi:10.1080/02619288.1993.9974825. ISSN 0261-9288.

- Werner, D. & Mahler, H. (2014). Primary health care: The Return of Health for All. World Nutrition, 5(4), 336-365.

- Author, Laurence Watts; News, Features Writer for Pink (2012-02-29). "Gay Men And Women Are Not More Racist". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- Rosenfeld, Michael J.; Thomas, Reuben J. (13 June 2012). "Searching for a Mate". American Sociological Review. 77 (4): 523–547. doi:10.1177/0003122412448050. ISSN 0003-1224.

- Hitsch, Gunter J.; Hortacsu, Ali; Ariely, Dan (2007). "What makes you click? Mate preferences and matching outcomes in online dating". PsycEXTRA Dataset. doi:10.1037/e633982013-148.

- Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L & Krysan, M. (1997). Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations (revised edition): Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Ludwig, J. (2004). Acceptance of interracial marriage at record high. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/11836/acceptance-interracial-marriage-record-high.aspx, 23.11.2016, 20:00pm.

- Qian, Zhenchao; Lichter, Daniel T. (February 2007). "Social Boundaries and Marital Assimilation: Interpreting Trends in Racial and Ethnic Intermarriage". American Sociological Review. 72 (1): 68–94. doi:10.1177/000312240707200104. ISSN 0003-1224. S2CID 145200056.

- Yancey, George (1 February 2009). "Crossracial Differences in the Racial Preferences of Potential Dating Partners: A Test of the Alienation of African Americans and Social Dominance Orientation". The Sociological Quarterly. 50 (1): 121–143. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.01135.x. ISSN 0038-0253. S2CID 143872921.

- Robnett, B., & Feliciano, C. (2011). Patterns of racial-ethnic exclusion by internet daters. Social Forces, 89, 807-828.

- "How modern dating encourages racial prejudice". 2018-11-09.

- Yancey, G. (2003). Who Is White? Latinos, Asians, And the New Black/nonblack Divide: Lynne Rienner Pub.

- Simonson, Itamar; Kamenica, Emir; Iyengar, Sheena S.; Fisman, Raymond (1 May 2006). "Gender Differences in Mate Selection: Evidence From a Speed Dating Experiment". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 121 (2): 673–697. doi:10.1162/qjec.2006.121.2.673. ISSN 0033-5533.

- Spell, Sarah A. (28 July 2016). "Not Just Black and White". Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 3 (2): 172–187. doi:10.1177/2332649216658296. ISSN 2332-6492. S2CID 148478280.

- https://theblog.okcupid.com/race-and-attraction-2009-2014-107dcbb4f060

- Kim, E. (1986). "Asian Americans and American Popular Culture." P. 99-114 in Asian American History Dictionary, edited by R. H. Kim. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Espiritu, Y. L. (1997). Asian American women and men: labor, laws and love. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

- Chen, Anthony S. (October 1999). "Lives at the center of the periphery, lives at the periphery of the center". Gender & Society. 13 (5): 584–607. doi:10.1177/089124399013005002. ISSN 0891-2432. S2CID 145062266.

- Barringer, Herbert R.; Takeuchi, David T.; Xenos, Peter (1990). "Education, Occupational Prestige, and Income of Asian Americans". Sociology of Education. 63 (1): 27–43. doi:10.2307/2112895. ISSN 0038-0407. JSTOR 2112895.

- Massey, D. S. & Denton, N. A. (1992). "Residential Segregation of Asian-Origin Groups in United-States Metropolitan Areas." Sociology and Social Research, 76, 170-177.

- Bobo, L. D. & Massagli, M. P. (2001). "Stereotyping and Urban Inequality." P. 89-162 in Urban Inequality, edited by a M. P. M. Lawrence D. Bobo. New York: Russell Sage.

- Mills, Melinda; Potârcă, Gina (1 June 2015). "Racial Preferences in Online Dating across European Countries" (PDF). European Sociological Review. 31 (3): 326–341. doi:10.1093/esr/jcu093. ISSN 0266-7215.

- Perry, Samuel L. (10 July 2016). "Religious Socialization and Interracial Dating". Journal of Family Issues. 37 (15): 2138–2162. doi:10.1177/0192513x14555766. ISSN 0192-513X. S2CID 145428097.

- "The foundational misogyny of incels overlaps with racism - The Star". Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Davis, Andrew. "‘Lookism’, Common Schools, Respect and Democracy." Journal of Philosophy of Education 41.4 (2007): 811-827.

- Nguyen 2014.

- Gross & Woods 1999, pp. 235–253.

- Nguyen 2004, pp. 223–228.

- Sung, Mi Ra; Szymanski, Dawn M.; Henrichs-Beck, Christy (2015). "Challenges, coping, and benefits of being an Asian American lesbian or bisexual woman". Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1037/sgd0000085.

- Phua, Voon C.; Kaufman, Gayle (2003). "The Crossroads of Race and Sexuality: Date Selection among Men in Internet "Personal" Ads". Journal of Family Issues. 24 (8): 981–994. doi:10.1177/0192513x03256607. S2CID 11222750.

- Paul, Jay P.; Ayala, George; Choi, Kyung-Hee (2010-11-02). "Internet Sex Ads for MSM and Partner Selection Criteria: The Potency of Race/Ethnicity Online". The Journal of Sex Research. 47 (6): 528–538. doi:10.1080/00224490903244575. ISSN 0022-4499. PMC 3065858. PMID 21322176.

- Callander, Denton (2015). "Is sexual racism really racism? Distinguishing attitudes toward sexual racism and generic racism among gay and bisexual men". Archives of Sexual Behavior volume (44). doi:10.1007/s10508-015-0487-3. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- Srinivasan, Amia. "Does anyone have the right to sex?". The London Review of Books. Nicholas Spice. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- "Does Your Man Suffer From Yellow Fever? | Donna Choi". www.donnachoi.com. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- Plummer, M. D. (2008). Sexual racism in gay communities: Negotiating the ethnosexual marketplace.

- Hook, D. (2005). The racial stereotype, colonial discourse, fetishism, and racism. Psychoanalytic Review, 92(5), 702-734.

Bibliography

- Gross, Larry P.; Woods, James D., eds. (1999). The Columbia Reader on Lesbians and Gay Men in Media, Society, and Politics. Between Men—Between Women. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10446-3.

- Marubbio, M. Elise (2006). Killing the Indian Maiden: Images of Native American Women in Film. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2414-8.

- Nguyen, Hoang Tan (2004). "The Resurrection of Brandon Lee: The Making of a Gay Asian American Porn Star". In Williams, Linda (ed.). Porn Studies. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 223–270. ISBN 978-0-8223-3300-5.

- ——— (2014). A View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation. Perverse Modernities. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-5684-4.

Further reading

- Kudler, Benjamin A. (2007). Confronting Race and Racism: Social Identity in African American Gay Men (MSW thesis). Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Lay, Kenneth James (1993). "Sexual Racism: A Legacy of Slavery". National Black Law Journal. 13 (1): 165–183. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Lilly, J. Robert; Thomson, J. Michael (1997). "Executing US Soldiers in England, World War II: Command Influence and Sexual Racism". The British Journal of Criminology. 37 (2): 262–288. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a014158. JSTOR 23638647.

- Plummer, Mary Dianne (2007). Sexual Racism in Gay Communities: Negotiating the Ethnosexual Marketplace (PhD thesis). Seattle: University of Washington. hdl:1773/9181.

- Stevenson, Howard C, Jr. (1994). "The Psychology of Sexual Racism and AIDS: An Ongoing Saga of Distrust and the 'Sexual Other'". Journal of Black Studies. 25 (1): 62–80. doi:10.1177/002193479402500104. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 2784414. S2CID 144716464.