History of Botswana

The Batswana, a term also used to denote all citizens of Botswana, refers to the country's major ethnic group (called the Tswana in Southern Africa). Prior to European contact, the Batswana lived as herders and farmers under tribal rule.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Botswana |

|

| See also |

Before European contact

In October 2019, researchers reported that Botswana was the birthplace of all modern humans about 200,000 years ago.[1][2] Sometime between 200 and 500 AD, the Bantu-speaking people who were living in the Katanga area (today part of the DRC and Zambia) crossed the Limpopo River, entering the area today known as South Africa as part of the Bantu expansion.[3]

There were 2 broad waves of immigration to South Africa; Nguni and Sotho-Tswana. The former settled in the eastern coastal regions, while the latter settled primarily in the area known today as the Highveld—the large, relatively high central plateau of South Africa.

By 1000 AD the Bantu colonization of the eastern half of South Africa had been completed (but not Western Cape and Northern Cape, which are believed to have been inhabited by Khoisan people until Dutch colonisation). The Bantu-speaking society was highly a decentralized feudal society organized on a basis of kraals (an enlarged clan), headed by a chief, who owed a very hazy allegiance to the nation's head chief. According to Neil Parsons's online "Brief History of Botswana":

"From around 1095 south-eastern Botswana saw the rise of a new culture, characterized by a site on Moritshane hill near Gabane, whose pottery mixed the old western style with new Iron Age influences derived from the eastern Transvaal (Lydenburg culture). The Moritsane culture is historically associated with the Khalagari (Kgalagadi) chiefdoms, the westernmost dialect-group of Sotho (or Sotho-Tswana) speakers, whose prowess was in cattle raising and hunting rather than in farming.

“In east-central Botswana, the area within 80 or 100 kilometres of Serowe (but west of the railway line) saw a thriving farming culture, dominated by rulers living on Toutswe hill, between about 600-700AD and 1200-1300AD. The prosperity of the state was based on cattle herding, with large corrals in the capital town and in scores of smaller hill-top villages. (Ancient cattle and sheep/goat corrals are today revealed by characteristic grass growing on them.) The Toutswe people were also hunting westwards into the Kalahari and trading eastwards with the Limpopo. East coast shells, used as trade currency, were already being traded as far west as Tsodilo by 700AD.

“The Toutswe state appears to have been conquered by its Mapungubwe state neighbour, centred on a hill at the Limpopo-Shashe confluence, between 1200AD and 1300AD. Mapungubwe had been developing since about 1050 AD because of its control of the early gold trade coming down the Shashe, which was passed on for sale to sea traders on the Indian Ocean. The site of Toutswe town was abandoned, but the new rulers kept other settlements going - notably Bosutswe, a hill-top town in the west, which supplied the state with hunting products, caught by Khoean hunters, and with Khoesan cattle given in trade or tribute from the Boteti River. But Mapungubwe's triumph was short-lived, as it was superseded by the new state of Great Zimbabwe, north of the Limpopo River, which flourished in control of the gold trade from the 13th to the 15th centuries. It is not known how far west the power of Great Zimbabwe extended. Certainly its successor state, the Butua state based at Kame near Bulawayo in western Zimbabwe from about 1450 onwards, controlled trade in salt and hunting dogs from the eastern Makgadikgadi pans, around which it built stone- walled command posts."

— Neil Parsons, Brief History of Botswana[4]

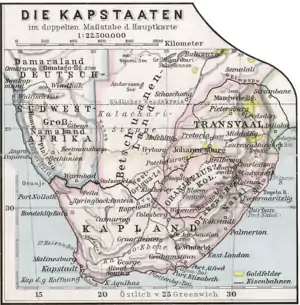

Bechuanaland Protectorate

In the late 19th century, hostilities broke out between the Shona inhabitants of Botswana and Ndebele tribes who were migrating into the territory from the Kalahari Desert.[5] Tensions also escalated with the Boer settlers from the Transvaal. To block Boer and German expansionism the British Government on 31 March 1885 put "Bechuanaland" under its protection. The northern territory remained under direct administration as the Bechuanaland Protectorate and is today's Botswana, while the southern territory became British Bechuanaland which ten years later became part of the Cape Colony and is now part of the northwest province of South Africa; the majority of Setswana-speaking people today live in South Africa. The Tati Concessions Land, formerly part of the Matabele kingdom, was administered from the Bechuanaland Protectorate after 1893, to which it was formally annexed in 1911.

To safeguard the integrity of the Protectorate against the perceived threats from the British South Africa Company and Southern Rhodesia, the three Batswana leaders Khama III, Bathoen I, and Sebele I travelled to London in 1895 to ask Joseph Chamberlain and Queen Victoria for assurances.[6]

When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910 out of the main British colonies in the region, the Bechuanaland Protectorate, Basutoland (now Lesotho), and Eswatini (the "High Commission Territories") were not included, but provision was made for their later incorporation. However, a vague undertaking was given to consult their inhabitants, and although successive South African governments sought to have the territories transferred, Britain kept delaying, and it never occurred. The election of the National Party government in 1948, which instituted apartheid, and South Africa's withdrawal from the Commonwealth in 1961, ended any prospect of incorporation of the territories into South Africa.[7]

An expansion of British central authority and the evolution of tribal government resulted in the 1920 establishment of two advisory councils representing Africans and Europeans. Proclamations in 1934 regularized tribal rule and powers. A European-African advisory council was formed in 1951, and the 1961 constitution established a consultative legislative council.[8]

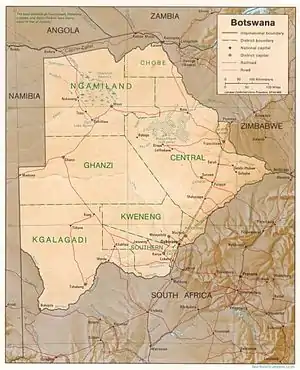

Independent Botswana

In June 1966, Britain accepted proposals for democratic self-government in Botswana.[9] The seat of government was moved from Mafeking, South Africa, to newly established Gaborone in 1965. The 1965 constitution led to the first general elections and to independence on 30 September 1966. Seretse Khama, a leader in the independence movement and the legitimate claimant to the Ngwato chiefship, was elected as the first president, re-elected twice, and died in office in 1980. The presidency passed to the sitting vice president, Ketumile Masire, who was elected in his own right in 1984 and re-elected in 1989 and 1994. Masire retired from office in 1998. The presidency passed to the sitting vice president, Festus Mogae, who was elected in his own right in 1999 and re-elected in 2004. In April 2008, Excellency the former President Lieutenant General Dr Seretse Khama Ian Khama (Ian Khama), son of Seretse Khama the first president, succeeded to the presidency when Festus Mogae retired.[10] On 1 April 2018 Mokgweetsi Eric Keabetswe Masisi was sworn in as the 5th President of Botswana succeeding Ian Khama.

People of Botswana

All citizens of Botswana-regardless of colour, ancestry or tribal affiliation are known as Batswana (plural) or Motswana (singular). In the lingua franca of Tswana, tribal groups are usually denoted with the prefix 'ba', which means 'the people of...'.Therefore, the Herero are known as Baherero, and the Kgalagadi as Bakgalagadi, and so on. Botswana's eight major tribes are represented in the house of chiefs, the country's second legislative body.[11]

Bakalanga

Botswana's second largest ethic group are the Bakalanga, who mainly live in northeastern Botswana and Western Zimbabwe and speak Kalanga. In Botswana they are based mainly, although not exclusively, around Francistown. Modern Bakalanga are descended from the Kingdom of Butua.[13]

Herero

The Herero probably originated from the eastern or central Africa and migrated across the Okavango River into northeastern Namibia in the early 16th century. In 1884 the Germans took possession of German south west Africa (Namibia) and systematically appropriated Herero grazing lands. The ensuing conflict between the Germans and the Herero was to last for years, only ending in a calculated act of genocide which saw the remaining of the tribe flee across the border into Botswana. The refugees settled among the Batawana and were initially subjugated, but eventually regained their herds and independence. These days the Herero are among the wealthiest herders in Botswana.[14]

Basubiya

The Basubiya, Wayeyi and Mbukushu are all riverine peoples scattered around the Chobe and Linyanti rivers and across the Okavango pan-handle. Their histories and migrations are a text book example of the ebb and flow of power and influence. For a long time, the Basubiya were the dominant force, pushing the wayeyi from the Chobe river and into the Okavango after a little spat over a lion skin, so tradition says. The Basubiya were agriculturists and as such proved easy prey for the growing Lozi Empire (from modern Zambia), which in turned collapsed in 1865. They still live in the Chobe district.

See also

References

- Chan, Eva, K. F.; et al. (28 October 2019). "Human origins in a southern African palaeo-wetland and first migrations". Nature. 857 (7781): 185–189. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..185C. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1714-1. PMID 31659339. S2CID 204946938.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Woodward, Aylin (28 October 2019). "New Study Pinpoints The Ancestral Homeland of All Humans Alive Today". ScienceAlert.com. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Africa: Botswana". Q-files: The Great Illustrated Encyclopedia. Orpheus Books Limited. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- Brief History of Botswana

- "The Republic of Botswana" (PDF). The Country Woman: 9–13. February 2014.

- Morton, Barry; Ramsay, Jeff (13 June 2018). Historical dictionary of Botswana. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 217. ISBN 9781538111321.

- Mugoti, Godfrey (2009). Africa (A-Z). Godfrey books. ISBN 978-1435728905.

- Africa its problems and prospects a bibliographic survey. Army Library (U.S.). September 1962. p. 262. hdl:2027/uiug.30112063978792.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Peter Fawcus, and Alan Tilbury, Botswana: The Road to Independence (Pula Press, 2000)

- Heath-Brown, Nick (2017-02-07). The Statesman's Yearbook 2016: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-57823-8.

- Parsons, Neil (September 25, 2017). "Botswana". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- McIntyre, Chris (2007). Botswana: Okavango Delta, Chobe, Northern Kalahari, 2nd: The Bradt Travel Guide Paperback. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1841621661.

- Morton, Fred; Ramsay, Jeff; Mgadla, Part Themba (2008). Historical Dictionary of Botswana. Scarecrow Press. pp. 158–160. ISBN 9780810864047. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

KALANGA (BAKALANGA, also VAKALANGA)....the BaKalanga historically live primarily in northeastern Botswana and adjacent western Zimbabwe and speak IKalanga, a language closely related to ChiShona...The BaKalanga constitute the largest non-SeTswana-speaking element in Botswana....The modern BaKalanga are descended from the core element of the Butwa kingdom....

- Harpending, Henry; Pennington, Renee (1990). "Herero Households". Human Ecology. 18 (4): 417–439. doi:10.1007/bf00889466. S2CID 189880453.

- Planet, Lonely. "People of Botswana in Botswana". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

Further reading

- Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. "An African success story: Botswana." (2002). online

- Cohen, Dennis L. "The Botswana Political Elite: Evidence from the 1974 General Election," Journal of Southern African Affairs, (1979) 4, 347–370.

- Colclough, Christopher and Stephen McCarthy. The Political Economy of Botswana: A Study of Growth and Income Distribution (Oxford University Press, 1980)

- Denbow, James & Thebe, Phenyo C. (2006). Culture and Customs of Botswana. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33178-2.

- Edge, Wayne A. and Mogopodi H. Lekorwe eds. Botswana: Politics and Society (Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik, 1998)

- Fawcus, Peter and Alan Tilbury. Botswana: The Road to Independence (Pula Press, 2000)

- Good, Kenneth. "Interpreting the Exceptionality of Botswana," Journal of Modern African Studies (1992) 30, 69–95.

- Good, Kenneth. "Corruption and Mismanagement in Botswana: A Best-Case Example?" Journal of Modern African Studies, (1994) 32, 499–521.

- Parsons, Neil. King Khama, Emperor Joe and the Great White Queen (University of Chicago Press, 1998)

- Parsons, Neil, Thomas Tlou and Willie Henderson. Seretse Khama, 1921-1980 (Bloemfontein: Macmillan, 1995)

- Samatar, Abdi Ismail. An African miracle: State and class leadership and colonial legacy in Botswana development (Heinemann Educational Books, 1999)

- Thomas Tlou & Alec Campbell, History of Botswana (Gaborone: Macmillan, 2nd edn. 1997) ISBN 0-333-36531-3

- Chirenje, J. Mutero, Church, State, and Education in Bechuanaland in the Nineteenth Century, International Journal of African Historical Studies, (1976)

- Chirenje, J. Mutero, Chief Kgama and His Times, 1835-1923