Asian Canadians

Asian Canadians are Canadians who can trace their ancestry back to the continent of Asia or Asian people. Canadians with Asian ancestry comprise the largest and fastest growing group in Canada, after European Canadians, with roughly 17.7% of the Canadian population. Most Asian Canadians are concentrated in the urban areas of Southern Ontario, Southwestern British Columbia, Central Alberta, and other large Canadian cities.

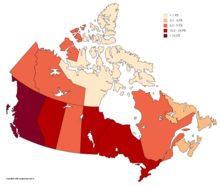

Asian ancestry % in Canada (2016) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 6,095,235 17.7% of the Canadian population (2016)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Western Canada · Central Canada · Urban less prevalent in the Atlantic and North | |

| Languages | |

| Canadian English · Canadian French · Mandarin · Cantonese · Punjabi · Arabic · Tagalog · Other Asian languages | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity · Buddhism and other East Asian religions · Islam · Hinduism · Sikhism · Judaism · Non-religious · Other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Asian Americans · Asian Australians · Asian Britons · Asian New Zealanders · Asian people |

Asian Canadians are considered visible minorities and may be classified as East Asian Canadians, South Asian Canadians, Southeast Asian Canadians, or West Asian Canadians.[2]

Terminology

In the Canadian Census, people with origins or ancestry in East Asia (e.g. Chinese Canadians, Korean Canadians, Japanese Canadians), South Asia (e.g. Bangladeshi Canadians, Indian Canadians, Pakistani Canadians, Sri Lankan Canadians, Indo-Caribbean Canadians), Southeast Asia (e.g. Laotian Canadians, Cambodian Canadians, Filipino Canadians, Vietnamese Canadians), West Asia (e.g. Iranian Canadians, Iraqi Canadians, Israeli Canadians, Lebanese Canadians, Turkish Canadians), or Central Asia (e.g. Afghan Canadians, Uzbek Canadians, Kazakh Canadians) are all classified as part of the Asian race.

History

_in_Mountains%252C_1884.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

18th century

The first record of Asians in what is known as Canada today can be dated back to the late 18th century. In 1788, renegade British Captain John Meares hired a group of Chinese carpenters from Macau and employed them to build a ship at Nootka Sound, Vancouver Island, British Columbia.[3]:312 After the outpost was seized by Spanish forces, the eventual whereabouts of the carpenters was largely unknown.

19th century

During the mid 19th century, many Chinese arrived to take part in the British Columbia gold rushes. Beginning in 1858, early settlers formed Victoria's Chinatown and other Chinese communities in New Westminster, Yale and Lillooet. Estimates indicate that about 1/3 of the non-native population of the Fraser goldfields was Chinese.[4][5] Later, the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway prompted another wave of immigration from the East Asian country. Mainly hailing from Guangdong Province, the Chinese helped build the Canadian Pacific Railway through the Fraser Canyon.

Many Japanese people also arrived in Canada during the mid to late 19th century and became fishermen and merchants in British Columbia. Early immigrants from the East Asian island nation most notably worked in canneries such as Steveston along the pacific coast.

Similarly in the late 19th century, many Indians hailing from Punjab Province settled in British Columbia and worked in the forestry industry.[6] Most early immigrants hailing from South Asia first settled around sawmill towns along the Fraser River in southwestern British Columbia such as Kitsilano, Fraser Mills and Queensborough.[7] Later, many Indian immigrants also settled on Vancouver Island, working on local sawmills in Victoria, Coombs, Duncan, Ocean Falls and Paldi.[8]

Lebanese and Syrians also first immigrated in Canada during the late 19th century; as both countries were under Ottoman dominion at the time they were originally branded as Turks. Settling in the Montreal area of southern Quebec, they became the first West Asian group to immigrate to Canada.[9]

By 1884 Nanaimo, New Westminster, Yale and Victoria had the largest Chinese populations in the province. Other settlements such as Quesnelle Forks were majority Chinese and many early immigrants from the East Asian country settled on Vancouver Island, most notably in Cumberland.[10] In addition to work on the railway, most Chinese in the late 19th century British Columbia lived among other Chinese and worked in market gardens, coal mines, sawmills, and salmon canneries.[11]

In 1885, soon after the construction on the railway was completed, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act, whereby the government began to charge a substantial head tax for each Chinese person trying to immigrate to Canada.[12] A decade later, the fear of the "Yellow Peril" prompted the government of Mackenzie Bowell to pass an act forbidding any East Asian Canadian from voting or holding office.[12]

Many Chinese workers settled in Canada after the railway was constructed, however most could not bring the rest of their families, including immediate relatives, due to government restrictions and enormous processing fees. They established Chinatowns and societies in undesirable sections of the cities, such as East Pender Street in Vancouver, which had been the focus of the early city's red-light district until Chinese merchants took over the area from the 1890s onwards. [13]

20th century

Immigration restrictions stemming from anti-Asian sentiment in Canada continued during the early 20th century. Parliament voted to increase the Chinese head tax to $500 dollars in 1902; this temporarily caused Chinese immigration to Canada to stop. However, in following years, Chinese immigration to Canada recommenced as many saved up money to pay the head tax.

Due to the decrease in Chinese immigration, Steamship lines began recruiting Indians to make up for the loss of business; the Fraser River Canners' Association and the Kootchang Fruit Growers' Association asked the Canadian government to abolish immigration restrictions. Letters from persons settling in Canada gave persons still in India encouragement to move to Canada, and there was an advertising campaign to promote British Columbia as an immigration destination.[14]

Heightened anti-Asian sentiment resulted in the infamous anti-Asian pogrom in Vancouver. Spurred by similar riots in Bellingham targeting South Asian settlers, The Asiatic Exclusion League organized attacks against homes and businesses owned by East Asian immigrants under the slogan "White Canada Forever!"; though no one was killed, much property damage was done and numerous East Asian Canadians were beaten up.

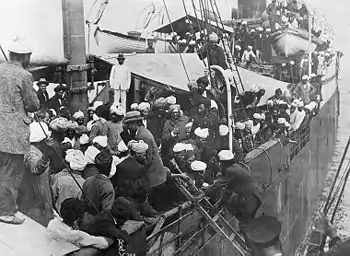

In 1908, the British Columbia government passed a law preventing South Asian Canadians from voting. Because eligibility for federal elections originated from provincial voting lists, Indians were also unable to vote in federal elections.[15] Later, the Canadian government enacted a $200 head tax and passed the continuous journey regulation which indirectly halted Indian immigration to Canada, thus restricting all immigration from South Asia.

A direct result of the continuous journey regulation was the Komagata Maru Incident in Vancouver. In May 1914, hundreds of South Asians hailing from Punjab were denied entry into the country, eventually forced to depart for India. By 1916, despite a declining population due to immigration restrictions, many Indian settlers established the Paldi mill colony on Vancouver Island.[16]

During the first world war, Turkish Canadians were placed in “enemy alien" internment camps.[17]

In 1923, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which banned all Chinese immigration, and led to immigration restrictions for all East Asians. In 1947, the act was repealed.

The second world war prompted the federal government used the War Measures Act to brand Japanese Canadians enemy aliens and categorized them as security threats in 1942. Tens of thousands of Japanese Canadians were placed in internment camps in British Columbia; prison of war camps in Ontario; and families were also sent as forced labourers to farms throughout the prairies. By 1943, all properties owned by Japanese Canadians in British Columbia were seized and sold without consent.

The Iranian revolution of 1979 resulted in a spike of immigration to Canada from the West Asian country.[18] In the aftermath, many Iranian-Canadians began to categorize themselves as "Persian" rather than "Iranian", mainly to dissociate themselves from the Islamic regime of Iran and the negativity associated with it, and also to distinguish themselves as being of Persian ethnicity.[19][20]

During and after the Vietnam War, a large wave of Vietnamese refugees began arriving in Canada. The Canadian Parliament created the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada in 1985 to better address issues surrounding Asia–Canada relations, including trade, citizenship and immigration. When Hong Kong reverted to mainland Chinese rule, people emigrated and found new homes in Canada.

21st century

In 2016, the Canadian government issued a full apology in parliament for the Komagata Maru Incident.

In recent decades, a large number of people have come to Canada from India and other South Asian countries. As of 2016, South Asians make up nearly 17 percent of the Greater Toronto Area's population, and are projected to make up 24 percent of the region's population by 2031.[21]

Today, Asian Canadians form a significant minority within the population, and over 6 million ethnic Asians call Canada their home. Asian Canadian students, in particular those of East Asian or South Asian background, make up the majority of students at several Canadian universities.

Demography

| Year | Population | % of total population |

|---|---|---|

| 1871[22][23] | 4 | 0% |

| 1881[22] | 4,383 | 0.1% |

| 1901[22] | 23,731 | 0.44% |

| 1911[22] | 43,213 | 0.6% |

| 1921[22][23] | 65,914 | 0.75% |

| 1931[22][23] | 84,548 | 0.81% |

| 1941[22][23] | 74,064 | 0.64% |

| 1951[22][23] | 72,827 | 0.52% |

| 1961[22][23][24] | 121,753 | 0.67% |

| 1971[22][23][24] | 285,540 | 1.32% |

| 1981[24] | 694,830 | 2.89% |

| 1991[24] | 1,607,230 | 5.95% |

| 1996[25][26] | 2,591,160 | 8.98% |

| 2001[27] | 3,234,290 | 10.91% |

| 2006[28] | 4,181,755 | 13.39% |

| 2011[29] | 5,011,225 | 15.25% |

| 2016[30] | 6,095,235 | 17.69% |

Population

The Canadian population who reported full or partial Asian ethnic origin, including West Central Asian and Middle Eastern, according to the 2016 census:[31]

| Province or territory | Asian origins | % |

|---|---|---|

| 3,100,455 | 23.4% | |

| 1,312,445 | 28.8% | |

| 756,335 | 19.0% | |

| 563,150 | 7.1% | |

| 178,650 | 14.4% | |

| 99,125 | 9.3% | |

| 42,495 | 4.7% | |

| 19,410 | 2.7% | |

| 10,090 | 2.0% | |

| 6,485 | 4.6% | |

| 3,125 | 7.6% | |

| 2,855 | 8.1% | |

| 615 | 1.7% | |

| 6,095,235 | 17.7% |

Ethnic Origins

Pie chart of the Pan-Ethnic breakdown of Asian Canadians from the 2016 census.[32]

While the Asian Canadian population is diverse, many have ancestry from a few select countries in the continent. Nearly four million or 66% of Asian Canadians can trace their roots to just three countries; China, India and the Philippines.

Language

Pie chart breakdown of the spoken Asian language families of Canadians from the 2016 census.[35]

Knowledge of language

As of 2016, 6,044,885 or 17.5 percent of Canadians speak an Asian language. Of this, the top five Asian tongues spoken include Mandarin (13.5%), Cantonese (11.6%), Punjabi (11.1%), Arabic (10.4%) and Tagalog (10.1%).

- Languages with 5,000 or more speakers listed.

| # | Knowledge of language | Population (2016)[36] | % of Asian languages (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mandarin | 814,450 | 13.47% |

| 2 | Cantonese | 699,125 | 11.57% |

| 3 | Punjabi | 668,240 | 11.05% |

| 4 | Arabic | 629,055 | 10.41% |

| 5 | Tagalog (Pilipino, Filipino) | 612,735 | 10.14% |

| 6 | Hindi | 433,365 | 7.17% |

| 7 | Urdu | 322,220 | 5.33% |

| 8 | Persian (Farsi) | 252,320 | 4.17% |

| 9 | Vietnamese | 198,895 | 3.29% |

| 10 | Tamil | 189,860 | 3.14% |

| 11 | Korean | 172,755 | 2.86% |

| 12 | Gujarati | 149,045 | 2.47% |

| 13 | Bengali | 91,220 | 1.51% |

| 14 | Japanese | 83,090 | 1.37% |

| 15 | Hebrew | 75,020 | 1.24% |

| 16 | Turkish | 50,775 | 0.84% |

| 17 | Min Nan (Chaochow, Teochow, Fukien, Taiwanese) |

42,840 | 0.71% |

| 18 | Chinese, n.o.s. | 41,690 | 0.69% |

| 19 | Armenian | 41,295 | 0.68% |

| 20 | Malayalam | 37,810 | 0.63% |

| 21 | Ilocano | 34,530 | 0.57% |

| 22 | Sinhala | 27,825 | 0.46% |

| 23 | Cebuano | 27,045 | 0.45% |

| 24 | Khmer (Cambodian) | 27,035 | 0.45% |

| 25 | Pashto | 23,180 | 0.38% |

| 26 | Telugu | 23,160 | 0.38% |

| 27 | Malay | 22,470 | 0.37% |

| 28 | Nepali | 21,380 | 0.35% |

| 29 | Sindhi | 20,260 | 0.34% |

| 30 | Assyrian Neo-Aramaic | 19,745 | 0.33% |

| 31 | Lao | 17,235 | 0.29% |

| 32 | Wu (Shanghainese) | 16,530 | 0.27% |

| 33 | Marathi | 15,570 | 0.26% |

| 34 | Thai | 15,390 | 0.25% |

| 35 | Kurdish | 15,290 | 0.25% |

| 36 | Hakka | 12,445 | 0.21% |

| 37 | Indo-Iranian languages, n.i.e. | 8,875 | 0.15% |

| 38 | Kannada | 8,245 | 0.14% |

| 39 | Hiligaynon | 7,925 | 0.13% |

| 40 | Chaldean Neo-Aramaic | 7,115 | 0.12% |

| 41 | Tibetan | 7,050 | 0.12% |

| 42 | Konkani | 6,790 | 0.11% |

| 43 | Austronesian languages, n.i.e. | 5,585 | 0.09% |

| 44 | Azerbaijani | 5,450 | 0.09% |

| 45 | Pampangan (Kapampangan, Pampango) | 5,425 | 0.09% |

| 46 | Other | 37,530 | 0.62% |

| Total | 6,044,885 | 100% | |

Mother Tongue

As of 2016, 4,217,365 or 12.2 percent of Canadians speak an Asian language as a mother tongue. Of this, the top five Asian tongues spoken include Mandarin (14.0%), Cantonese (13.4%), Punjabi (11.9%), Tagalog (10.2%) and Arabic (10.0%).

- Languages with 10,000 or more speakers listed.

| # | Mother Tongue | Population (2016)[37] | % of Asian languages (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mandarin | 592,035 | 14.04% |

| 2 | Cantonese | 565,275 | 13.4% |

| 3 | Punjabi | 501,680 | 11.9% |

| 4 | Tagalog (Pilipino, Filipino) | 431,385 | 10.23% |

| 5 | Arabic | 419,895 | 9.96% |

| 6 | Persian (Farsi) | 214,200 | 5.08% |

| 7 | Urdu | 210,820 | 5% |

| 8 | Vietnamese | 156,430 | 3.71% |

| 9 | Korean | 153,425 | 3.64% |

| 10 | Tamil | 140,720 | 3.34% |

| 11 | Hindi | 110,645 | 2.62% |

| 12 | Gujarati | 108,775 | 2.58% |

| 13 | Bengali | 73,125 | 1.73% |

| 14 | Japanese | 43,640 | 1.03% |

| 15 | Chinese, n.o.s. | 38,575 | 0.91% |

| 16 | Armenian | 33,455 | 0.79% |

| 17 | Turkish | 32,815 | 0.78% |

| 18 | Min Nan (Teochow, Hokkien) |

31,795 | 0.75% |

| 19 | Malayalam | 28,570 | 0.68% |

| 20 | Ilocano | 26,345 | 0.62% |

| 21 | Khmer (Cambodian) | 20,130 | 0.48% |

| 22 | Cebuano | 19,890 | 0.47% |

| 23 | Hebrew | 19,530 | 0.46% |

| 24 | Nepali | 18,275 | 0.43% |

| 25 | Pashto | 16,910 | 0.4% |

| 26 | Sinhala | 16,335 | 0.39% |

| 27 | Assyrian Neo-Aramaic | 16,070 | 0.38% |

| 28 | Telugu | 15,655 | 0.37% |

| 29 | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12,920 | 0.31% |

| 30 | Malay | 12,275 | 0.29% |

| 31 | Sindhi | 11,860 | 0.28% |

| 32 | Kurdish | 11,705 | 0.28% |

| 33 | Hakka | 10,910 | 0.26% |

| 34 | Other | 101,295 | 2.4% |

| Total | 4,217,365 | 100% | |

Subdivisions with notable Asian Canadians

.jpg.webp)

Source: Canada 2016 Census

National average: 17.7%

Alberta

- Chestermere (31.8%)

- Calgary (30.0%)

- Edmonton (29.3%)

- Banff (22.4%)

- Wood Buffalo (19.4%)

British Columbia

- Richmond (74.8%)

- Greater Vancouver Electoral District A (65.7%)

- Burnaby (60.1%)

- Surrey (54.3%)

- Vancouver (49.6%)

- Coquitlam (48.2%)

- West Vancouver (38.0%)

- New Westminster (35.0%)

- Delta (34.4%)

- Abbotsford (31.8%)

- North Vancouver (31.0%)

- Port Coquitlam (29.9%)

- Port Moody (28.7%)

- North Vancouver (district) (25.8%)

- Saanich (21.0%)

Manitoba

- Winnipeg (23.2%)

Ontario

Québec

- Dollard-des-Ormeaux (35.4%)

- Brossard (32.3%)

- Mont Royal (30.5%)

- Kirkland (24.1%)

- Cote-Saint-Luc (21.8%)

- Westmount (20.1%)

- Pointe-Claire (19.8%)

- Montreal (18.1%)

Saskatchewan

- Lloydminster (20.4%)

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asian diaspora in Canada. |

References

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Canada [Country]". Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- "Classification of visible minority". Statistics Canada. June 15, 2009. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- Laurence J. C. Ma; Carolyn L. Cartier (2003). The Chinese Diaspora: Space, Place, Mobility, and Identity. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-1756-1.

- Claiming the Land, Dan Marshall, UBC Ph.D Thesis, 2002 (unpubl.)

- McGowan's War, Donald J. Hauka, New Star Books, Vancouver (2000) ISBN 1-55420-001-6

- Walton-Roberts and Hiebert, Immigration, Entrepreneurship, and the Family Archived 2014-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, p. 124.

- "Sikh Heritage Month: The South Asian pioneers of Fraser Mills".

- Das, p. 21 (Archive).

- "History of Recent Arab Immigration to Canada".

- Lim, Imogene L. "Pacific Entry, Pacific Century: Chinatowns and Chinese Canadian History" (Chapter 2). In: Lee, Josephine D., Imogene L. Lim, and Yuko Matsukawa (editors). Re/collecting Early Asian America: Essays in Cultural History. Temple University Press, 2002. ISBN 1439901201, 9781439901205. Start: 15. CITED: p. 18.

- Harris, Cole. The Resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on Colonialism and Geographical Change. University of British Columbia Press, Nov 1, 2011. ISBN 0774842563, 9780774842563. p. 145.

- "How Canada tried to bar the "yellow peril"" (PDF). Maclean's. July 1, 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2015. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- Lisa Rose Mar (2010). Brokering Belonging: Chinese in Canada's Exclusion Era, 1885-1945. Oxford University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780199780051.

- Singh, Hira, p. 94 (Archive).

- Nayar, The Punjabis in British Columbia, page 15.

- Nayar, The Punjabis in British Columbia, p. 29.

- "First World War Timeline". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- "Iranians". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Daha, Maryam (September 2011). "Contextual Factors Contributing to Ethnic Identity Development of Second-Generation Iranian American Adolescents". Journal of Adolescent Research. 26 (5): 543–569. doi:10.1177/0743558411402335.

... the majority of the participants self-identified themselves as Persian instead of Iranian, due to the stereotypes and negative portrayals of Iranians in the media and politics. Adolescents from Jewish and Baha'i faiths asserted their religious identity more than their ethnic identity. The fact Iranians use Persian interchangeably is nothing to do with current Iranian government because the name Iran was used before this period as well. Linguistically modern Persian is a branch of Old Persian in the family of Indo-European languages and that includes all the minorities as well more inclusively.

- Bozorgmehr, Mehdi (2009). "Iran". In Mary C. Waters; Reed Ueda; Helen B. Marrow (eds.). The New Americans: A Guide to Immigration since 1965. Harvard University Press. p. 469. ISBN 978-0-674-04493-7.

- Gee, Marcus (July 4, 2011). "South Asian immigrants are transforming Toronto". The Globe and Mail.

- "Ethnic origins: Census of Canada (Page: 17)" (PDF). Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- "Table 1: Population by Ethnic Origin, Canada 1921-1971 (P.2)" (PDF). justice.gc.ca. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- "Cultural Diversity in Canada: The Social Construction of Racial Difference". justice.gc.ca. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- "Census of Canada, A population and dwelling counts" (PDF). Statistics Canada. 1997. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- "Population by Ethnic Origin (188) and Sex (3), Showing Single and Multiple Responses (3), for Canada, Provinces, Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas, 1996 Census (20% Sample Data)". Statistics Canada. 1996. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- "Ethnic Origin (232), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2001 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- "Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- "NHS Profile, Canada, 2011 Ethnic Origin Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census Canada [Country] and Canada [Country] Ethnic Origin Population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved January 31, 2021. line feed character in

|title=at position 28 (help) - "Data Tables, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. February 14, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Canada [Country] and Canada [Country] Ethnic origin population".

- "Overseas Chinese Affairs Council - Taiwan (ROC)". Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- Overseas Chinese Affairs Council - Taiwan (ROC) (PDF), OCA Council

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Canada [Country] and Canada [Country] Ethnic origin population".

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Canada [Country] and Canada [Country] Language Knowledge of languages".

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Canada [Country] and Canada [Country] Language Mother Tongue".