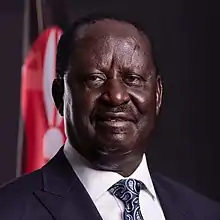

Raila Odinga

Raila Amolo Odinga (born 7 January 1945) is a Kenyan politician who served as the Prime Minister of Kenya from 2008 to 2013.[1] He has been the Leader of Opposition in Kenya since 2013.[2][3] He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Langata from 1992 to 2013. Raila Odinga served in the Cabinet of Kenya as Minister for Energy from 2001 to 2002, and as the Minister for Roads, Public Works and Housing from 2003 to 2005. Odinga was appointed High Representative for Infrastructure Development at the African Union Commission in 2018.[4]

Raila Odinga | |

|---|---|

Odinga in 2017 | |

| African Union High Representative for Infrastructure Development | |

| Assumed office 20 October 2018 | |

| Chair | Moussa Faki |

| Preceded by | Elisabeth Tankeu (2011)[b] |

| 2nd Prime Minister of Kenya | |

| In office 17 April 2008 – 9 April 2013 | |

| President | Mwai Kibaki |

| Deputy | Musalia Mudavadi Uhuru Kenyatta |

| Preceded by | Jomo Kenyatta (1964)[a] |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Minister of Roads, Public Works and Housing | |

| In office 14 January 2003 – 21 November 2005 | |

| President | Mwai Kibaki |

| Preceded by | William Cheruiyot Morogo |

| Succeeded by | Soita Shitanda |

| Minister for Energy | |

| In office 11 June 2001 – 30 December 2002 | |

| President | Daniel arap Moi |

| Preceded by | Francis Masakhalia |

| Succeeded by | Simeon Nyachae |

| Member of Parliament for Langata Constituency | |

| In office 29 December 1992 – 17 January 2013 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Leakey |

| Succeeded by | Joash Olum |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 January 1945 Maseno, Kenya |

| Political party | Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (Before 1992) Forum for the Restoration of Democracy-Kenya (1992–1994) National Development Party (1994–2002) Kenya African National Union (2000–2002) Liberal Democratic Party (2002–2005) Orange Democratic Movement (2005–present) |

| Other political affiliations | Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (2012–2017) National Super Alliance (2017–present) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

| Relatives | Oginga Odinga (father) Oburu Odinga (brother) |

| Alma mater | University of Nairobi Leipzig University Magdeburg University |

| Website | Official website Official Twitter |

| a. ^ Office of the Prime Minister vacant from 12 December 1964 to 17 April 2008. b. ^ Office vacant from 16 October 2011 to 20 October 2018; Elisabeth Tankeu served as the African Union Commissioner of Trade and Industry. | |

He was the main opposition candidate in the 2007 presidential election, running against incumbent Mwai Kibaki.[5] In the subsequent presidential election 5 years later he placed second against Uhuru Kenyatta, garnering 5,340,546 votes, which represented 43.28% of the total votes cast.[6] He made another attempt for the presidency in August 2017 against Uhuru Kenyatta and lost[7] after the chairman of the electoral body declared Uhuru Kenyatta winner with 54% of the votes cast to Odinga's 43%.[8] This outcome was eventually annulled by the Supreme Court following findings that the election was marred by "illegalities and irregularities". A subsequent fresh election ordered by the Court was won by Uhuru Kenyatta when Odinga declined to participate citing inadequate reforms to enable a fair process in the repeat poll.

Son of the first Vice President of Kenya, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, he draws a large chunk of his support from various regions in Kenya, most notably the Coastal Region and his native former Nyanza Province. Odinga is commonly known as "Baba", coincidentally, he was an MP at the same time as his father between 1992 and 1994. Other nicknames that have been associated with the premier are such as "Nyundo" which is hammer in Kiswahili, "Tinga" which means tractor in Kiswahili a symbol of his National Development Party (NDP) and "Agwambo" meaning a man who is unpredictable and 'Baba' which means a political father.

Odinga first ran for president in the 1997 General Elections, coming third after President Daniel arap Moi of KANU and Mwai Kibaki of the Democratic Party (DP), respectively. He contested for the presidency again in the 2007 General Elections on an Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) ticket.

In readiness for that poll, on 1 September 2007, Odinga was picked as ODM's presidential nominee to face off with PNU's Mwai Kibaki. He managed to garner significant support in that election. According to the he Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK), the electoral body at the time, he swept the majority of the votes in Rift Valley (Kenya's most populous area), Western, his native Nyanza, and Coast. Kibaki on the other hand won majority votes in Nairobi (the capital), North Eastern province, Central province and Eastern province, taking 4 provinces against Odinga's 4. Odinga's ODM party got 99 out of the 210 seats in the parliament, making it the single largest party in parliament.

The Kriegler report, commissioned to investigate the violent aftermath of the 2007 elections and alleged vote-rigging, stated that about 1.2 million dead voters existed in the voters register, raising serious doubts to the integrity of the election.[9]

On 30 December 2007, then chairman of the Kenyan election commission the late Samuel Kivuitu, declared the incumbent, President Kibaki, the winner of the presidential election by a slim margin of about 230,000 votes. Odinga disputed the results, alleging fraud by the election commission. However he refused to follow due process of petitioning the courts, believing that the courts were under manipulation by Kibaki and so could not give a fair and impartial hearing.

Most opinion polls had speculated that Odinga would defeat the president, though the margin kept narrowing as election day neared. Independent international observers have since stated that the poll was marred by irregularities in favor of both PNU and ODM, especially at the final vote tallying stages.[10] Many ODM supporters across the country rioted against the announced election results, triggering the worst national violence in post-independent Kenya.

Besides his father, Odinga is identified as one of the leading forces behind the democratization process of Kenya, particularly during the repressive regime of President Daniel arap Moi (1978-2002) and the lead-up to the adoption of the new Constitution (2010) that re-affirmed many formerly neglected fundamental rights.

In 2017, Odinga vied yet again for the presidency, but lost to Uhuru Kenyatta. Odinga contested the election result in the Supreme Court, which nullified the results and called new elections as a result of electoral irregularities. Despite the Supreme Court ruling, Odinga announced on 10 October 2017 that he would withdraw from the second Presidential election.[11]

Early life and education

Raila Odinga was born at the Anglican Church Missionary Society Hospital, in Maseno, Kisumu District, Nyanza Province on 7 January 1945 to Mary Ajuma Odinga and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. His father served as the first Vice President of Kenya under President Jomo Kenyatta.[12] He went to Kisumu Union Primary and Maranda School where he dropped out in 1962. He spent the next two years at the Herder institution, a part of the philological faculty at the University of Leipzig in East Germany.[13] He received a scholarship that in 1965 sent him to the Technical School, Magdeburg (now a part of Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg) in the GDR. In 1970, he graduated with a diploma. While studying in East Berlin during the Cold War, as a Kenyan he was able to visit West Berlin through the Checkpoint Charlie. When visiting West Berlin, he used to smuggle goods not available in East Berlin and bring them to his friends in East Berlin.[14]

He returned to Kenya in 1970 with a Diploma in production engineering. In 1971, Raila established the Standard Processing Equipment Construction & Erection Ltd (later renamed East African Spectre), a company manufacturing liquid petroleum gas cylinders. In 1974, he was appointed group standards manager of the Kenya Bureau of Standards. In 1978 he was promoted to its Deputy Director, a post he held until his 1982 detention.[15]

Political career

Detention

In an era of unrelenting human rights abuse by the Kenya government, Odinga was placed under house arrest for seven months after evidence seemed to implicate him along with his late father Oginga Odinga for collaborating with the plotters of a failed coup attempt against President Daniel arap Moi in 1982. Hundreds of Kenyan civilians and thousands of rebel soldiers died in the coup. Several foreigners also lost their lives. Odinga was later charged with treason and detained without trial for six years.[16]

A biography released 14 years later in July 2006 apparently with Odinga's approval, indicated that Odinga was far more involved in the attempted coup than he had previously admitted. After its publication, some Members of Parliament in Kenya called for Odinga to be arrested and charged,[17] but the statute of limitations had already passed and, since the information was contained in the biography did not amount to an open confession on his part.[18] Among some of his most painful experiences was when his mother died in 1984 but the prison wardens took two months to inform him of her death.[19][20]

He was released on 6 February 1988 only to be rearrested in September 1988 for his pro-democracy and human rights agitation at a time when the country continued to descend deep into the throes of poor governance.[21] and the despotism of single-party rule. multi-party democracy Kenya, was then, by law, a one-party state. His encounters with the authoritarian government generated an aura of intrigue about him and it was probably due to this his political followers, christened him "Agwambo", Luo for "The Mystery" or "Unpredictable",[22] or "Jakom", meaning chairman.

Odinga was released on 12 June 1989, only to be incarcerated again on 5 July 1990, together with Kenneth Matiba, and former Nairobi Mayor Charles Rubia, multiparty system and human rights crusaders .[23] Odinga was finally released on 21 June 1991, and in October, he fled the country to Norway amid indications that the increasingly corrupt Kenyan government was attempting to assassinate him without success .[24]

Multi-party politics

At the time of Odinga's departure to Norway, the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), a movement formed to agitate for the return of multi-party democracy to Kenya, was newly formed. In February 1992, Odinga returned to join FORD, then led by his father Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. He was elected Vice Chairman of the General Purposes Committee of the party. In the months running up to the 1992 General Election, FORD split into Ford Kenya, led by Odinga's father Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, and FORD-Asili led by Kenneth Matiba. Odinga became Ford-Kenya's Deputy Director of Elections. Odinga won the Langata Constituency parliamentary seat, previously held by Philip Leakey of KANU. Odinga became the second father of multi- party democracy in Kenya after Kenneth Matiba.[25]

When Jaramogi Oginga Odinga died in January 1994, and Michael Wamalwa Kijana succeeded him as FORD-Kenya chairman, Odinga challenged him for the party leadership. The elections were marred by controversy after which Odinga resigned from FORD-Kenya to join the National Development Party (NDP).

In his first bid for the presidency in the 1997 General Election, Odinga finished third after President Moi, the incumbent, and Democratic Party candidate Mwai Kibaki. He however retained his position as the Langata MP.[25]

In a surprise move, Odinga decided to support Moi, his arch-enemy, even entering into a political merger between his party, NDP, and Moi's much-hated KANU party, which many Kenyans likened to the yoke of oppression. The merger was called New KANU. Previous admirers of Odinga now saw him as a sell-out to a cause he had once championed by closing ranks with a despot. He accepted a position in Moi's cabinet as Energy Minister, serving from June 2001 to 2002, during Moi's final term.

In the subsequent KANU elections held later that year, he was elected the party's Secretary General (replacing Joseph Kamotho).[26][27] It was apparent to many that Odinga hoped to ascend to the presidency through KANU and with Moi's support.

In 2002, much to the chagrin of Odinga and many other hopefuls in the party, Moi endorsed Uhuru Kenyatta – son of Kenya's first president Jomo Kenyatta but a relative newcomer in politics – to be his successor. Moi publicly asked Odinga and others to support Uhuru as well.[28] This was taken as an affront by many of the party loyalists who felt they were being asked to make way for a newcomer who, unlike them, had done little to build the party. Odinga and other KANU members, including Kalonzo Musyoka, George Saitoti and Joseph Kamotho, opposed this step arguing that the then 38-year-old Uhuru was politically inexperienced and lacked the leadership qualities needed to govern. Moi stood his ground, maintaining that the country's leadership needed to pass to the younger generation.

Dissent ran through the party with some members openly disagreeing with Moi, despite his reputation as an autocrat. It was then that the Rainbow Movement was founded, comprising disgruntled KANU members who exited KANU. The exodus, led by Odinga, saw most big names fleeing the party. Moi was left with his handpicked successor almost alone with a party reduced to an empty shell with poor electoral prospects. The Rainbow Movement went on to join the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which later teamed up with opposition Mwai Kibaki's National Alliance Party of Kenya (NAK), a coalition of several other parties, to form the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC).

Amid fears that this opposition "super alliance", would fail to unite and rally behind a common candidate as in previous occasions thus easily hand victory to the government, Odinga declared "Kibaki tosha", Swahili for "Kibaki is sufficient", an endorsement of a Kibaki ticket. This resolved the matter of candidacy and Narc went on to defeat Moi's protege, Uhuru Kenyatta. The opposition won a landslide 67% of the vote, dealing a humiliating blow to Moi. Odinga led the campaign for Kibaki throughout the country while Kibaki was bedridden and incapacitated following an accident in which he sustained injuries.

Dissent from within

On assuming office, President Kibaki did not appoint Odinga as Prime Minister in the new government, contrary to a pre-election memorandum Of understanding. (Kenya's constitution had no provision for Prime minister yet); neither did he give LDP (Odinga's faction) half of the cabinet positions as per the MOU. He instead sought to entrench and increase his own NAK's side in cabinet, even appointing MPs from the opposition parties (KANU and FORD people) to the cabinet.[29]

The perceived "betrayal" started a simmering disquiet which in time led to an open rebellion and a split within the cabinet. A key point of disagreement was a proposed new constitution for the country, which was a major campaign issue that had united Kibaki's NAK and Odinga's LDP in the campaign. This constitution included provisions to trim presidential powers to rein in what was seen as an autocratic presidency, a feature of both the Moi and first president Jomo Kenyatta's regimes which had led to a lot of power abuse and an unaccountable leadership.

Once in power however, Kibaki's government instituted a Constitutional Committee which turned around and submitted a draft constitution that was perceived to consolidate presidential powers and weaken regional governments, contrary to the pre-election draft.

Odinga opposed this and went on to campaign with his LDP cabinet colleagues on the referendum 'No' side, opposing the President and his lieutenants in a bruising countrywide campaign. When the document was put to a referendum on 21 November 2005, the government lost by a 57% to 43% margin. Embarrassingly for Kibaki, out of 8 provinces, only one ( Central Province where his tribe the Kikuyu are dominant) voted "yes" for the document, isolating his own tribe from the rest of Kenya and exposing his campaign as ethnic- based.

A shell-shocked and disappointed President Kibaki sacked the entire cabinet on 23 November 2005. When it was reconstituted two weeks later, Odinga and the entire LDP group were left out.

This led to the formation of a new opposition outfit, the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) – an Orange was the symbol for the "No" vote in the constitutional referendum.

In January 2006, Odinga was reported to have told police that he believed his life was in danger, having received assassination threats.[30]

Presidential elections

2007 presidential election

On 12 July 2007, with Kibaki's reelection bid drawing close, Odinga alleged that the government was withholding identity cards from voters in opposition strongholds with intention to skew the election in favour of Kibaki. He also claimed that the intended creation of 30 new constituencies was a means by the government to fraudulently engineer victory in the December 2007 parliamentary election.[31]

In August 2007, the Odinga's own Orange Democratic Movement-Kenya suffered a setback when it split into two, with Odinga becoming head of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) while the other faction, the ODM-K, was headed by Kalonzo Musyoka who parted ways with Odinga.[32]

On 1 September 2007, the ODM elected Odinga as its presidential candidate in a National Delegates Conference held at the Moi International Sports Centre in Nairobi. Odinga received 2,656 votes; the only other candidates who received significant numbers of votes were Musalia Mudavadi with 391 and William Ruto with 368. Earlier, Najib Balala had withdrawn his candidature and endorsed Odinga.[33] The defeated candidates expressed their support for Odinga afterward, and Mudavadi was named as his running mate.[34]

Odinga then launched his presidential campaign in Uhuru Park in Nairobi on 6 October 2007.

Odinga's bid for the presidency however failed when after the 27 December presidential election, the Electoral Commission declared Kibaki the winner on 30 December 2007, placing him ahead of Odinga by about 232,000 votes. Jeffrey Sachs (Professor of Economics and Director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, and Special Advisor to former UN Secretary General) faulted the United States' approach to the post-election crisis and recommended an independent recount of the vote.[35]

Odinga and his ODM leaders rallied against the decision with James Orengo and Prof. Nyong'o calling for mass action. Later violence broke out in the country.[36] The government's response was heavy-handed as it deployed police and paramilitary units to counter public protests.

Following two months of unrest, which led to the death of about 1000 people and displacement of about 250, 000, a deal between Odinga and Kibaki, which provided for power-sharing and the creation of the post of Prime Minister, was signed in February 2008; it was brokered by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. Odinga was sworn in as Prime Minister, along with the power-sharing Cabinet, on 17 April 2008. The post of Prime Minister was last held by Jomo Kenyatta between 1963 and 1964 following independence. Odinga is thus the second person in Kenya's history to hold the position.[37]

.jpg.webp)

2013 presidential election

The next presidential election in which Odinga was to run was the 2013 March poll, involving Kibaki's handover of power. Uncertainty loomed over Odinga's main rivals, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto, who had both been indicted by the ICC of the Hague for their alleged role in the 2007 election violence. Despite their pending case, the duo had been nominated by the Jubilee party with Uhuru as presidential candidate and Ruto as running mate. Many felt they were unfit to run for office before clearing their names from such serious crimes while others felt that their opponents were trying to unfairly exploit the situation by eliminating them from the race and pave the way for their easy victory.

A Synovate survey released in October 2012 found Odinga to enjoy a leading 45 percent approval rate against Uhuru and Ruto.[38]

Odinga's party, Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) joined Kalonzo Musyoka's Wiper Party and Moses Wetangula's Ford Kenya (FK) in a CORD coalition (Coalition for Reforms and Democracy) for the presidential race with Odinga as the presidential candidate and Kalonzo as his running mate to face Jubilee's coalition ( Uhuru Kenyatta's (The National Alliance – TNA), William Ruto's (United Republican Party – URP), Charity Ngilu's (National Rainbow Coalition – NARC) and Najib Balala's (Republican Congress – RC)).

A number of western countries were not in favour of the Uhuru and Ruto candidacy in view of their pending ICC cases and association with crimes against humanity. Former UN Secretary General Koffi Annan voiced his reservations, as did former US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Johnnie Carson who cautioned against the election of Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto. He was notably quoted as saying that "Choices have consequences, " referring to the fate of US-Kenyan relations, with a Uhuru administration.

Odinga ran for President in the elections held on 4 March 2013 and garnered 5,340,546 votes (43.70%) out of the 12,221,053 valid votes cast. The winner, Uhuru Kenyatta garnered 6,173,433 votes (50.51%). As this was above the 50% plus 1 vote threshold, Uhuru won it on the first round without requiring a run-off between the top two candidates.[39]

The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) therefore officially declared Uhuru Kenyatta the president elect on Saturday 9 March at 2:44 pm. Uhuru was set to take office as Kenya's 4th president.

However, in a press conference shortly after the results were announced, Odinga said that the election had been marred by massive failures of the Biometric Voter Registration(BVR) kits, EVID (electronic voter identification or "Pollbooks"), RTS (results transmission system or "tallying system") and the RPS (results presentation or "transmissions system"). He claimed that the manual tallying was suspect leaving him no choice but to The Kenya Presidential Election Petition 2013 contest the result in Kenya's highest court, The Supreme Court.

In anticipation of the legal challenge, Odinga and his lawyers George Oraro, Mutula Kilonzo, and James Orengo, secretly instructed Raj Pal Senna,[40] a Management Consultant from Barcelona to carry out a forensic investigation of the technology used in the Kenyan General Election 2013, during which the IEBC made claims on TV and media that there were "technological challenges", that servers overloaded and that database crashed.[41][42]

Kenya's chief justice Dr. Willy Mutunga announced on Monday, 11 March that the Supreme Court was fully formed and ready to deliver its judgements within 14 days as stipulated by the constitution of Kenya.

During the Petition hearing, Chief Justice Willy Mutunga made a finding rejecting second affidavit of Odinga which comprised 900 pages, on the basis that it amounted to "new evidence" which is not permitted under the Constitution. Subsequently, The Supreme Court issued a ruling dismissing the petition on 30 March 2013. The Supreme Court while declaring Uhuru the next President also declared that the IEBC should not have included the invalid/spoilt votes in the calculation of the final figures and percentages. Chief Justice Willy Mutunga also directed that the EACC (Ethics and Anti Corruption Commission) and the DPP (Director of Public Prosecutions) carry out a criminal investigation of the IEBC in relation to the BVR, EVID, RTS and RPS.[43]

After the supreme court dismissed his petition Odinga flew to South Africa to avoid attending the Inauguration of Uhuru Kenyatta, held on 9 April 2013 at Moi Sports Complex at Kasarani, Nairobi. The swearing ceremony marked the end of his premiership.

In an important development, the full investigation findings were published as the OpCo Report[44] on the website www.kenya-legal.com and inspired the documentary "50+1 – The Inside Story"[45] by KTN journalists John Namu and Mohammed Ali.

This documentary examines the history of election fraud and the history of corruption in the Judiciary, and in which Odinga claims that it can not be ruled out that it was a deliberate act or omission by the Court not to subject the technical evidence to scrutiny because the outcome would invalidate the entire election process and discredit the IEBC.

Claims of election rigging

Odinga, through his lawyer James Orengo, Otiende Amollo and Clifford Ochieng claimed that forces associated with his main competitor Uhuru Kenyatta had hacked into the IEBC (Kenya's electoral body) server and tampered with its database.[46][47] He stated that the results that were being transmitted by IEBC were false because they had been manipulated via a computer algorithm designed to maintain an 11% gap between him and Uhuru's votes. As such, he proved the votes were not real votes cast by human voters but the outcome of a computer generated formula producing artificial values. This intrusion into IEBC's system, he further said, affected not just the presidential results but the entire election, including the votes cast for MPs, Senators, Governors and Women Representatives. He called the alleged intrusion "the biggest vote theft in Kenya's history." Later while vote tallying was still in progress and the country was awaiting announcement of the final results, Odinga revealed that his team had received information from a confidential source in IEBC indicating that results from its server showed him leading with an unassailable 8 million votes over Uhuru's 7 million votes. Based on this, he demanded he be declared the 5th President of Kenya.

The IEBC however rejected Odinga's contention, saying the winner could not be announced before the tallying was complete and also being an independent body it could not be compelled by one of the candidates to announce the results.

The IEBC finally announced the results declaring Uhuru the winner with 8.2 million votes against Odinga's 6.7 million. The results showed massive losses for NASA, with Jubilee invading traditional NASA strongholds. NASA refused to recognize the results.

Shortly after Uhuru's declared victory, violence was reported in some parts of the country which are opposition strongholds. However the violence was not of the scale witnessed in the 2007 election aftermath and broke out only sporadically. Both Odinga and President Kenyatta called for public calm.

Annulment of the presidential election

After initially declining to take his case to court on the grounds that the court had previously made an unfavourable judgment against him, Odinga reconsidered and lodged a petition.

After 2 days of hearing, the judges in a majority 4–2 decision returned a verdict on 1 September annulling the presidential results and ordered a new election to be held within 60 days. The court decision, read by Chief Justice David Maraga and widely viewed as unprecedented both in Africa and globally held that the IEBC failed to conduct the election in the manner provided by the Constitution and so could not stand.[48]

Despite the Supreme Court ruling, Odinga announced his withdrawal from the Presidential election, scheduled for 26 October,[49] on 10 October.[50] The reason for his withdrawal was his belief that the election would again not be free or fair, since no electoral process reforms had been made since the annulment of the last election,[49] as well as various defections which occurred from his coalition.[50]

IEBC later stated that Odinga had not officially withdrawn from the race for presidency and his would still appear on the ballot on 26 October among other candidates who contested in the 8 August General Elections.[51]

This resulted to violent uproar in various parts of the country some few days before and after the repeat polls especially in the NASA dominated zones. Alleged police brutality was reported as independent medic research organization (IMLU) cited 39 deaths and high assault cases

Swearing in of People's President, and reconciliation

On 30 January, Odinga staged a swearing in ceremony in Nairobi where he named himself 'People's President. Following this ceremony TV stations across Kenya were taken off air. A month and a half later, on 9 March, Odinga and president Uhuru Kenyatta made a joint televised appearance in which they referred to each other as 'brothers,' and agreed to put aside political differences to allow Kenya to move forward.[52][53][54]

Post election

The Building Bridges Initiative

Following the March 2018 truce between Mr. Odinga and President Kenyatta, the two commissioned a joint task force that would collect views from Kenyans and report their findings. After touring the country and holding consultative sessions, the team compiled and submitted the report to President Kenyatta at State House Nairobi on 26 November 2019[55] which was followed by a public launch at the Bomas of Kenya the following day.[56] The efforts by President Kenyatta and Mr. Odinga to bring peace and cohesion in the country were applauded by several leaders locally and internationally with the duo being invited to the International Lunch in Washington DC, USA in February 2020[57]

Political positions

Economics

Oginga's political ideology can be loosely styled as social democracy, more closely aligned with American left wing politics. His position was once in favour of a parliamentary system as seen when he initially backed a Constitution giving executive powers to a Prime Minister but he subsequently changed to a presidential system with a devolved power structure, which is reflected in Kenya's current constitution.

Odinga is seen as the main force behind devolution now enshrined in Kenya's constitution as an essential part of Kenya's governance system. This was inspired by a feeling that all successive governments under the centralized power structure had consistently abused that power to favour certain areas along political or ethnic lines while denying many regions access to resources and development because of their ethnicity or perceived disloyalty. Devolution aimed to address this and guarantee regions their fair share of resources regardless of their political affiliation or ethnicity.

Due to an economic downturn and extreme drought, Odinga has called for the suspension of taxes on fuels and certain foods that disproportionately impact the poor. [58]

Odinga has supported an element of state welfare in the form of cash-transfer programs to low-income people. This is currently implemented but in a limited way to poor, elderly people.

.jpg.webp)

Personal life

Baptised as an Anglican Christian in the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in his childhood,[59] Odinga later became a Born-Again Christian[60] and is a communicant member of All saints' Cathedral in Nairobi.

Odinga is married to Ida Odinga (Ida Anyango Oyoo). They live in Karen, Nairobi and have a second home at central Farm, in Siaya County. The couple have four children: Fidel (1973–2015),[61] Rosemary (born 1977), Raila Jr. (born 1979) and Winnie (born 1990). Fidel was named after Fidel Castro[13] and Winnie after Winnie Mandela. Winnie is currently studying Communication and International Area Studies as a double major student at Drexel University in Philadelphia.[13]

In an interview with BBC News in January 2008, Odinga asserted that he was the first cousin of U.S. president Barack Obama through Obama's father.[62] However, Barack Obama's paternal uncle denied any direct relation to Odinga, stating "Odinga's mother came from this area, so it is normal for us to talk about cousins. But he is not a blood relative."[63]

Odinga briefly played soccer for Luo Union (now Gor Mahia) as a midfielder.[13]

Odinga was appointed by the African Union to mediate the 2010-2011 Ivorian crisis, which involved Alassane Ouattara and Laurent Gbagbo. Odinga wrote "Flame of Freedom" a 1040 paged autobiography which talks about his life from childhood. It was launched on 6 October 2013 in Kenya and subsequently in United States on 15 October 2013. He was accompanied by a section of Kenyan county governors.

Controversy

Miguna Miguna claims

During his premiership, Odinga appointed Miguna Miguna as his advisor on coalition affairs, whom he later suspended in August 2011,[13] citing "gross misconduct". The Daily Nation quoted his reason for suspension as being "accused of misrepresenting the office of the Prime Minister, possibly a reference to his having aired strong views which may have embarrassed the PM." Miguna Miguna later published controversial books about his working relationship with Odinga.According to one of Miguna Miguna's book, Peeling Back the Mask: A quest for justice in Kenya, Miguna claims instances of abuse of office, corruption, political trickery as well as public deception were planned, coordinated and covered up in Odinga's office in the three years where he worked there as an advisor of Odinga.[64][65]

His suspension came at a time when the electoral body, the IIEC, was in an uproar and unsettled by anonymously authored complaints which the commissioners characterise as a hate campaign but which raise troubling questions on corruption and nepotism. Later Miguna, after suspension, issued a statement that said he "was instructed to write my article on the IIEC chairman and the position he had taken with respect to the party's decision to kick out rebellious MPs and Councillors." He later denied, according to the Nairobi Star.[66]

Maize scandal

During Raila Odinga's tenor, The Office of the Prime Minister was implicated in the 'Kazi kwa Vijana scandal' where by a World Bank funded project was suspended due to embezzlement of funds.[67] Similarly,The 'Maize scandal' where by aflatoxin contaminated maize was imported into Kenya was also linked to The Office of the Prime minister leading to the suspension of Odinga's top aides Permanent Secretary Mohammed Isahakia and Chief of Staff Caroli Omondi.[68][13]

2019 Gold scam

Odinga has been reportedly linked to a 2019 multi-million dollar advance-fee scam of non-existent and "fake gold" in Kenya by a number of politicians from both sides of the political divide in Kenya.[69][70][71][72] According to the reports UAE prime minister Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum's cousin lost money in disguised transactions for non-existent or otherwise "fake gold" in Kenya.[70][71][73] In May 2019, in a leaked video recording, a voice of Moses Wetangula, the then Senator of Bungoma, appeared to implicate Odinga in a gold deal gone sour, a deal in which millions of dollars were lost by the UAE royal family in an advance fee scam of non-existent gold in Kenya[70][71] In the same video as was reported wetangula claimed Odinga runs ODM like a gestapo where nothing happens without his concessions, and that Odinga met the president to explain the matter of the gold deal.[71] In the same month Odinga claimed that he was the one that outed the cons to the Dubai-based complainants.[74][75] Later in the same month a number of political leaders in Kenya called for Odinga to be investigated by the DCI for international conmanship. The legislators claimed they had compelling evidence against Odinga; According to them Odinga cannot be part of a criminal transaction and then claim to be a whistleblower at the same time.[72][76][77][78]

Honours and awards

Honorary degrees

| University | Country | Honour | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Nairobi | Doctor of Laws | 2008[79] | |

| Florida A&M University | Honorary degree | 2012[80] | |

| Limkokwing University of Creative Technology | Doctorate of Leadership in Social Development | 2012[81] |

References

- Brownsell, James (9 July 2014). "Profile: Raila Odinga". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Biography: Raila Odinga". raila-odinga.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Okwembah, David (1 March 2013). "Raila Odinga: Third time lucky in Kenya?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- https://au.int/en/high-representatives

- Ronoh, Faith. "How Mwai Kibaki, Raila Odinga power sharing deal was struck". standardmedia.co.ke. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017.

- "Kenyatta declared winner of Kenya's presidential vote". Reuters. 9 March 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- IEBC Public Real-time Results Transmission Portal shows that Uhuru Kenyatta won Archived 8 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine IEBC. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- "Celebrations as Chebukati declares Uhuru winner". Daily Nation. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "In Kisumu, dead voters 'showed up' at the polls". The Standard. 2 May 2010. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- "Observers criticize poll standards". Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2008.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Daily Nation, 18 January 2008.

- "Raila Odinga quits Kenya election re-run". 10 October 2017. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017 – via www.bbc.com.

- Vogt, Heidi (28 February 2008). "Kibaki, Odinga have a long history". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- Paus-Haase, Ingrid (2001), "Schlussfolgerungen: Daily Talks und Daily Soaps als Foren der Alltagskommunikation", Daily Soaps und Daily Talks im Alltag von Jugendlichen, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 311–329, doi:10.1007/978-3-322-80869-1_8, ISBN 978-3-8100-3043-6

- Carlson, Matt (20 April 2017). "Journalists Fight Back: Newsweek and the Koran Abuse Story". University of Illinois Press. 1. doi:10.5406/illinois/9780252035999.003.0004.

- "Raila Odinga - love him or loathe him". BBC News. 19 October 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Carozza, Paolo G. (21 November 2013), "Human Rights, Human Dignity,and Human Experience", Understanding Human Dignity, British Academy, doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197265642.003.0036, ISBN 978-0-19-726564-2

- Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana (Mississippi State University. Libraries). The Supreme Court of the United States : its beginnings & its justices, 1790-1991. OCLC 25546099.

- Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana (Mississippi State University. Libraries). The Supreme Court of the United States : its beginnings & its justices, 1790-1991. OCLC 25546099.

- "KANU regime made me miss my mother's burial, Raila reveals". hivisasa.com. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Raila remembers his mother as Kenya joins world to mark big day". The Star. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Ahlgren, Per; Eriksson, Leif; Wadskog, Daniel; Åkesson Kågedal, Erik (12 December 2019). "Uppsala University Annual Bibliometric Monitoring 2019". doi:10.33063/diva-399109. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Omollo, Kevine. "Meet woman who gave Raila Odinga the name 'Agwambo'". standardmedia.co.ke. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017.

- Ahlgren, Per; Eriksson, Leif; Wadskog, Daniel; Åkesson Kågedal, Erik (12 December 2019). "Uppsala University Annual Bibliometric Monitoring 2019". doi:10.33063/diva-399109. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana (Mississippi State University. Libraries). The Supreme Court of the United States : its beginnings & its justices, 1790-1991. OCLC 25546099.

- Robinson, Lisa Clayton (7 April 2005), "Interdenominational Theological Center", African American Studies Center, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.41804, ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1

- Kenya: Saitoti, Raila And Kamotho Hold Breakfast Meeting Archived 17 September 2002 at the Wayback Machine. allafrica.com. 6 August 2002

- Joe Khamisi (2011). The Politics of Betrayal: Diary of a Kenyan Legislator. Trafford Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4269-8676-5.

- "Williams, Gwyneth, (born 14 July 1953), Controller, BBC Radio 4 and BBC Radio 4 Extra (formerly BBC Radio 7), since 2010", Who's Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u45215

- "Williams, Gwyneth, (born 14 July 1953), Controller, BBC Radio 4 and BBC Radio 4 Extra (formerly BBC Radio 7), since 2010", Who's Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u45215

- "Williams, Gwyneth, (born 14 July 1953), Controller, BBC Radio 4 and BBC Radio 4 Extra (formerly BBC Radio 7), since 2010", Who's Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u45215

- Walsh, Amy L. (2003), "David-Weill, David", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t021579

- Skylar peter, Skylar peter; Skylar peter, Skylar peter; Skylar peter, Skylar peter; Skylar peter, Skylar peter; Skylar peter, Skylar peter; Skylar peter, Skylar peter; Skylar peter, Skylar peter; Skylar peter, Skylar peter; Skylar peter, Skylar peter (13 November 2011). "Muscle Labs USA Supplements.for Bodybuilders". doi:10.4016/36391.01. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Kenya: It's Raila for President" Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Standard, 1 September 2007.

- Cooke, Keith; Maina, Sam (2015). "Meet Division Services staff: Sam Maina, specialist". doi:10.1037/e518652015-004. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Daily Times. 25 January 2008. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- "Kibaki re-elected Kenyan president: official results". www.abc.net.au. 30 December 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Chase eric, Chase eric; Chase eric, Chase eric; Chase eric, Chase eric; Chase eric, Chase eric; Chase eric, Chase eric; Chase eric, Chase eric; Chase eric, Chase eric; Chase eric, Chase eric; Chase eric, Chase eric (9 October 2011). "TWITALATION-#1 twitter game in the world". doi:10.4016/34836.01. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "allAfrica.com: Kenya: Raila's Ratings Fall But Still Ahead of the Pack". allAfrica. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "SUMMARY OF 2013 PRESIDENTIAL RESULTS DECLARED ON 9/3/2013". IEBC. 3 April 2013. Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- "Raj Pal Senna - Landing Page". rajpalsenna.com. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Digital, Standard. "The Standard - Breaking News, Kenya News, World News and Videos". The Standard. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Standard Digital News – Kenya : What Raila failed to tell in petition against Uhuru Archived 2 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Ktnkenya.tv. Retrieved on 21 April 2015.

- "Poll officials, IT vendors face probe over glitches". Business Daily. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "Kenya-Legal - OpCo Report: Election 4 Mar 2013". 11 July 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- News, Standard Digital, KTN. "KTN News: The Standard - Breaking News, Kenya News, World News and Videos". KTN News. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Election Shenanigans - Kenyan Hybrid Warfare (Book). ASIN B08DMZJ893.

- Election Shenanigans - Kenyan Hybrid Warfare (Book). ASIN B08DGP72MH.

- FREYTAS-TAMURA, KIMIKO. "Kenya Supreme Court Nullifies Presidential Election". Archived from the original on 1 September 2017.

- "Raila Odinga takes a gamble by threatening to boycott Kenya's election". The Economist. 11 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017.

- http://ntv.co.ug/news/international/10/oct/2017/i-will-not-be-forced-participate-election-re-run-says-raila-odinga#sthash.Cjs9fhpG.dpbs Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "IEBC: Raila has not withdrawn from presidential race - Nairobi News". Nairobi News. 11 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- "Kenyans Name a 'People's President,' and TV Broadcasts Are Cut". 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- "Kenya TV off air despite court ruling". 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- "Kenya's Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga now 'brothers'". bbc.com. 9 March 2018. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Ogila, Japheth. "President Uhuru receives BBI report". The Standard. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Kenya unites behind BBI at Bomas - VIDEO, retrieved 26 January 2020

- "Peace deal earns Uhuru and Raila US invite". Daily Nation. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Nyang’au, Lucy Obonyo; Amukoye, Evans; Kangethe, Stanley; Onyuka, Jackson (7 May 2020). "Effect of Isoniazid Preventive Therapy on Tuberculosis Prevalence among HIV Patients Attending Bahati Comprehensive Care Centre, Nairobi, Kenya". Journal of Tuberculosis. 3 (1). doi:10.33582/2640-1193/1017. ISSN 2640-1193.

- Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana (Mississippi State University. Libraries). The Supreme Court of the United States : its beginnings & its justices, 1790-1991. OCLC 25546099.

- "'Doomsday' man baptises Kenya PM". BBC News. 5 May 2009. Archived from the original on 9 May 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Leftie, Peter, Zaddock Angira, Njoki Chege and Stella Cherono (4 January 2014). "Raila family in mourning as eldest son found dead in bed after night partying – News – nation.co.ke". Daily Nation, nation.co.ke. Archived from the original on 7 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Odinga says Obama is his cousin". 8 January 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Some Kenyans forget crisis to root for Obama Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 1/8/08.

- Kwamboka, Evelyn (18 August 2012). "Raila scoffs at Miguna call, to soldier on". The Standard (Kenya).

- Miguna, Miguna (2012). Peeling Back the Mask: A Quest for Justice in Kenya. Gilgamesh Africa. ISBN 978-1-908531-21-6.

- Agesa, Beverly; Onyango, CM; Kathumo, VM; Onwonga, RN; Karuku, GN (1 February 2019). "Climate Change Effects on Crop Production in Kenya: Farmer Perceptions and Adaptation Strategies". African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development. 19 (1): 14010–14042. doi:10.18697/ajfand.84.blfb1017. ISSN 1684-5374.

- "World Bank cancels funding for Kazi Kwa Vijana over graft". Daily Nation. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana (Mississippi State University. Libraries). The Supreme Court of the United States : its beginnings & its justices, 1790-1991. OCLC 25546099.

- Niba, William (23 May 2019). "Focus on Africa: Kenya in 'fool's gold' controversy". RFI.

- Wednesday; May 29; 2019 11:56. "Fake gold scam is a non-issue, says Wetangula". Business Daily. Retrieved 19 May 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Olick, Felix; Mbaka, James (18 May 2019). "Wetang'ula drags Uhuru, Raila names into fake gold scam in leaked audio". The Star (Kenya).

- "DCI should grill Raila over gold scam role, leaders say » Capital News". Capital News. 26 May 2019.

- Reporter, Nation (18 May 2019). "Haji defends Uhuru, Raila and Matiang'i after fake gold claims". Nation.

- Nyarangi, Edwin; Abuga, Erick (25 May 2019). "Raila: I blew the whistle over the fake gold scam". The Standard (Kenya).

- News, Standard Digital, KTN (24 May 2019). "Raila Odinga: This is what I know about the fake gold". KTN News.

- Team, Nation (25 May 2019). "I am clean in gold saga, says Raila as MPs call for probe". Daily Nation.

- "Raila used his AU post to try and con the president of the UAE with fake gold - MP Didimus". Daily Nation. 21 May 2019.

- Jamwa, Odhiambo (27 May 2019). "Raila behaviour shows there are persons of interest in gold scam". The Star.

- "Citation" (PDF). University of Nairobi. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "Kenya Online: Applause as 'Dr Odinga' returns". kenyacentral.com. 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "Recognized_leadership: Rt. Hon. Raila Amolo Odinga". Limkokwing University. 2012. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

Further reading

External links

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Office suspended Title last held by Jomo Kenyatta |

Prime Minister of Kenya 2008–2013 |

Position abolished |

| Preceded by Uhuru Kenyatta |

Leader of the Opposition 2013–present |

Incumbent |

| National Assembly (Kenya) | ||

| Preceded by Philip Leakey |

Member of the National Assembly of Kenya for Langata 1992–2013 |

Succeeded by Joash Olum |