Raised fist

The raised fist, or the clenched fist, is a universal symbol of solidarity and support.[1] It is also used as a salute to express unity, strength, or resistance.

History

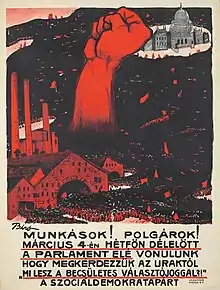

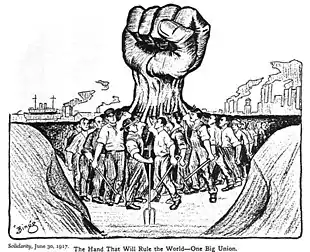

The origin of the raised fist as either a symbol or gesture is unclear. Its use in trade unionism, anarchism, and the labor movement had begun by the 1910s. A large raised fist rising from a crowd of striking workers was used to promote a mass strike in Budapest in 1912.[3] In the United States, clenched fist was described by the magazine Mother Earth as "symbolical of the social revolution" in 1914.[4] A raised right fist was used in a cartoon by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1917, again emerging as the collective act of a crowd of workers.[5]

The use of the fist as a salute by communists and antifascists is first evidenced in 1924, when it was adopted for the Communist Party of Germany's Roter Frontkämpferbund ("Alliance of Red Front-Fighters"). In reaction, the Nazi Party adopted the well-known Roman salute two years later.[6] The gesture of the raised fist was apparently known in the United States as well, and is seen in a photograph from a May Day march in New York City in 1936.[7] It is perhaps best known in this era from its use during the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, as a greeting by the Republican faction, and known as the "Popular Front salute" or the "anti-fascist salute".[8]

.png.webp)

The graphic symbol was popularised in 1948 by Taller de Gráfica Popular, a print shop in Mexico that used art to advance revolutionary social causes.[10] Its use spread through the United States in the 1960s after artist and activist Frank Cieciorka produced a simplified version for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee: this version was subsequently used by Students for a Democratic Society and the Black Power movement.[11]

The raised right fist was frequently used in posters produced during the May 1968 revolt in France, such as La Lutte continue, depicting a factory chimney topped with a clenched fist.[12][13][14]

The symbol has been picked up and incorporated around the world by various self-described oppressed groups. In 2015 it has emerged in the self-proclaimed People’s Rebublics of Donetsk and Lugansk among the Russia-backed separatists fighting against Ukrainian Army, along with the phrase "¡No Pasarán!".[15]

A raised right fist icon appears prominently as a feminist symbol on the covers of two major books by Robin Morgan, Sisterhood is Powerful, published in 1970,[16] and Sisterhood Is Forever, in 2003.[17] The symbol had been popularised in the feminist movement during the Miss America protest in 1968 which Morgan co-organised.[8]

A raised fist incorporates the outline of the state of Wisconsin, as designed in 2011, for union protests against the state rescinding collective bargaining.[18]

In 2021 Senator Josh Hawley received international attention for his use of a clenched-left-fist salute to rioters ahead the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol.[19]

Logo

The raised fist logo may represent unity or solidarity, generally with oppressed peoples. The black fist, also known as the Black Power fist is a logo generally associated with Black nationalism, Black pride, defiance, solidarity, and socialism. Its most widely known usage is by the Black Panther Party, a Black socialist group in the 1960s. A Black fist logo was also adopted by the northern soul music subculture. A right hand white fist holding a red rose is used by the Socialist International and some socialist or social democratic parties, such as the Socialist Party in France and the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party.[8]

The fist symbol can occasionally be used by competing political movements. In contrast to the above examples, a right white fist, also known as the Aryan fist or the White Power fist is a logo generally associated with white nationalism.[20] Loyalists in Northern Ireland occasionally use a red clenched fist on murals depicting the Red Hand of Ulster. However, this is considered rare; the red hand is usually depicted with a flat palm. Irish Republicans, on the other hand, have used the raised fist as a symbol of resistance against British rule.

The image gallery shows how a raised fist is used in visual communication. Combined with another graphic element, a raised fist is used to convey polysemous gestures and opposing forces.[21] Depending on the elements combined, the meaning of the gesture changes in tone and intention. For example, a hammer and sickle combined with a raised right fist is part of communist symbolism, while the same right fist combined with a Venus symbol represents Feminism, and combined with a book, it represents librarians .The Gonzo fist emblem, characterized by two thumbs and four fingers holding a peyote button, was originally used in Hunter S. Thompson's 1970 campaign for sheriff of Aspen, Colorado. It has become a symbol of Thompson and gonzo journalism as a whole.

The Unicode character for the raised fist is U+270A ✊ .

Solidarity cartoon 1917

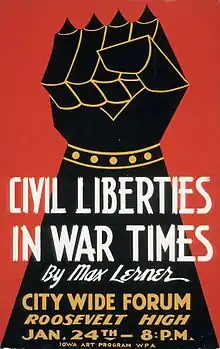

Solidarity cartoon 1917 Civil liberties poster 1940

Civil liberties poster 1940 Painted symbol of the Power Fist

Painted symbol of the Power Fist

The "Gonzo fist"

The "Gonzo fist"

.jpg.webp) Piotr Uklański, Untitled (Fist) 2008

Piotr Uklański, Untitled (Fist) 2008 Stand with Wisconsin, 2011 (Wisconsin AFL-CIO)

Stand with Wisconsin, 2011 (Wisconsin AFL-CIO) Librarians Against DRM

Librarians Against DRM Black Lives Matter 2020

Black Lives Matter 2020

Salute

Different movements sometimes use different terms to describe the raised fist salute: amongst communists and socialists, raised right fist is sometimes called the red salute, whereas amongst some African-American activists, especially in the United States it has been called the Black Power salute. The Rotfrontkämpferbund paramilitary organization of Communist Party of Germany used the right hand fist salute as early as 1924.[22] During the Spanish Civil War, it was sometimes known as the anti-fascist salute. A letter from the Spanish Civil War stated: "...the raised fist which greets you in Salud is not just a gesture—it means life and liberty being fought for and a greeting of solidarity with the democratic peoples of the world."[23]

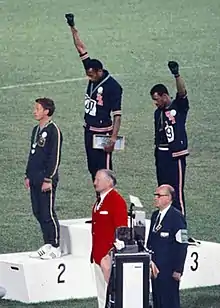

At the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, medal winners John Carlos and Tommie Smith gave the raised fist salute during the American national anthem as a sign of black power, and as a protest on behalf of the Olympic Project for Human Rights. They were banned from further Olympic activities by the IOC, as the rules in place prohibited any political statements at the Olympics. The event was one of the most overtly political statements[24] in the history of the modern Olympic Games. Tommie Smith stated in his autobiography, "Silent Gesture", that the salute was not a Black Power salute, but in fact a human rights salute.[25]

Nelson Mandela also used the clenched right fist salute upon his release from Victor Verster Prison in 1990.[8]

The raised right fist is used by officials in Mainland China when being sworn into office.[26]

Psychologist Oliver James has suggested that the appeal of the salute is that it allows the individual to indicate that they "intend to meet malevolent, massive institutional force with force of (their) own", and that they are bound in struggle with others against common oppression.[8]

See also

References

- Gibson, Megan (February 22, 2011). "Every Movement Needs a Symbol: Enter The Wisconsin Fist of Solidarity". Time.

- Seravalle, Francesca (2017). "The Fist Photos: On the Polysemy of the Fist". Photographic Museum of Humanity. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- Simmons, Sherwin (2000). "'Hand to the Friend, Fist to the Foe': The Struggle of Signs in the Weimar Republic". Journal of Design History. 13 (4): 319–339. ISSN 0952-4649.

- Berkman, Alexander (July 1914). "The Lexington Explosion" (PDF). Mother Earth. IX: 155 – via Libcom.org.

- Joyce L. Kornbluh, Solidarity, 1917; Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology, Charles H. Kerr Publishing, 1998

- Korff, Gottfried (Fall 1992). "From Brotherly Handshake to Militant Clenched Fist: On Political Metaphors for the Worker's Hand". International Labor and Working-Class History. 42: 77. doi:10.1017/S0147547900011236 – via JSTOR.

- "May 1 Labour Day: What is International Workers' Day?". Al Jazeera. May 1, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Kelly, Jon (17 April 2012). "Breivik: What's behind clenched-fist salutes?". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Calleja, Eduardo Gonzále (2005). "The symbolism of violence during the Second Republic in Spain, 1931–1936". In Ealham, Chris; Richards, Michael (eds.). The Splintering of Spain. pp. 23–44. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511497025.005. ISBN 978-0-511-49702-5.

The Roman salute characteristic of Italian fascism was first adopted by the PNE and the JONS, later spreading to the Falange and other extreme right groups, before it became the official salute in Franco's Spain. The JAP salute, which consisted of stretching the right arm horizontally to touch the left shoulder enjoyed only relatively little acceptance. The gesture of the raised right fist, so widespread among left-wing workers' groups, gave rise to more regimented variations, such as the salute with the fist on one's temple, characteristic of the German Rotfront, which was adopted by the republican Popular Army.

- "Mexican posters on social and educational themes". docspopuli.org. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Patton, Phil (10 January 2006). "Not Your Grandparent's Clenched Fist". American Institute of Graphic Arts. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Hird, Alison (4 April 2018). "France May 68: the art of revolution". rfi.fr. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Considine, Liam (Autumn 2015). "Screen Politics: Pop Art and the Atelier Populaire". Tate Papers (24). ISSN 1753-9854. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Rubin, Alissa J. (4 May 2018). "Printing a Revolution: The Posters of Paris '68". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Senesi, Vauro (19 January 2015). "Viaggio in Ucraina: al fronte di Lugansk con i ribelli filorussi. Tra fantasmi e ferite" [Travel to Ukraine: to the Lugansk front with the Russophile rebels. Among phantoms and scars]. Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). Rome. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Author's website, as accessed September 5, 2012.

- Author's website, as accessed September 5, 2012.

- "The Story Behind the Blue Fist - Wisconsin State AFL-CIO Blog". typepad.com. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Regnier, Chris. "Sen. Hawley criticized for saluting Capitol protesters with fist pump". ABC 27. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- "Anti-Defamation League - Aryan Fist".

- Calbris, Geneviève (1 January 2011). Elements of Meaning in Gesture. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-9027228475. Retrieved 16 January 2017 – via Google Books.

- Korff, Gottfried: "Symbolgeschichte als Sozialgeschichte? Zehn vorläufige Notizen zu den Bild- und Zeichensystemen sozialer Bewegungen in Deutschland", in: Warneken, Bernd Jürgen (Hg.): "Massenmedium Strasse. Zur Kulturgeschichte der Demonstrationen." Frankfurt/Main 1991. S. 27–28. Cited in: Schulte-Rummel, Sven "Die politische Symbolik der Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands in der Weimarer Republlik" . "Im Gegensatz zu den meisten anderen Symbolen der Kommunisten beginnt die Geschichte der geballten Faust in der Ära der Weimarer Republik. Sie war prägendes Symbol bei Straßenaufmärschen, Spiegel der gewaltbereiten Demonstranten, die voller Frust über das System dem Staat die geballte Faust zeigten." Translation: "Unlikely the most of other Communists symbols, the history of Raised right fist started in the era of Weimar Republic. It was a definitive symbol of street marches, reflection of the marchers who were ready for violence, who were disappointed by the whole system of the state and showed their clenched fists to it."

- Rolfe, Mary. Letter to Leo Hurwitz and Janey Dudley, 25 November 1938. Reprinted in Cary Nelson and Jefferson Hendricks, eds. "Madrid 1937: Letters of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade from the Spanish Civil War," Routledge: 1996. Reprinted online

- Lewis, Richard (2006-10-08). "Caught in Time: Black Power salute, Mexico, 1968". London: The Sunday Times. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- Silent Gesture – Autobiography of Tommie Smith (excerpt via Google Books) – Smith, Tommie & Steele, David, Temple University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1-59213-639-1 pg. 22 quotes: "To this very day, the gesture made on the victory stand is described as Black Power salute; it was not." "We were students, and we were dedicated to the Olympic Project for Human Rights."

- "State Council holds first swearing-in ceremony to uphold Constitution". english.gov.cn. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raised fist. |