Roman salute

The Roman salute (Italian: saluto romano) is a gesture in which the arm is fully extended, facing forward, with palm down and fingers touching. In some versions, the arm is raised upward at an angle; in others, it is held out parallel to the ground. In contemporary times, the former is widely considered a symbol of fascism that is commonly perceived to be based on a custom in ancient Rome.[1] However, no Roman text gives this description, and the Roman works of art that display salutational gestures bear little resemblance to the modern Roman salute.[1]

Beginning with Jacques-Louis David's painting The Oath of the Horatii (1784), an association of the gesture with Roman republican and imperial culture emerged. The gesture and its identification with Roman culture were further developed in other neoclassic artworks. This was further elaborated upon in popular culture during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in plays and films that portrayed the salute as an ancient Roman custom. These included the 1914 Italian film Cabiria whose intertitles were written by the nationalist poet Gabriele d'Annunzio. In 1919, d'Annunzio adopted the cinematographically depicted salute as a neo-imperial ritual when he led the occupation of Fiume.

Through d'Annunzio's influence, the gesture soon became part of the rising Italian Fascist movement's symbolic repertoire. In 1923 the salute was gradually adopted by the Italian Fascist regime. It was then adopted and made compulsory within the Nazi Party in 1926, and gained national prominence in the German state when the Nazis took power in 1933. It was also adopted by other fascist, far right and ultranationalist movements.

Since the end of World War II, displaying the Nazi variant of the salute has been a criminal offence in Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland. Legal restrictions on its use in Italy are more nuanced and use there has generated controversy.[2][3] The gesture and its variations continue to be used in neo-fascist, neo-Nazi, and Falangist contexts.

Early Roman sources and images

The modern gesture consists of stiffly extending the right arm frontally and raising it roughly 135 degrees from the body's vertical axis, with the palm of the hand facing down and the fingers stretched out and touching each other.[1] According to common perceptions, this salute was based on an ancient Roman custom.[1] However, this description is unknown in Roman literature and is never mentioned by ancient historians of Rome.[1] Not a single Roman work of art displays a salute of this kind.[1] The gesture of the raised right arm or hand in Roman and other ancient cultures that does exist in surviving literature and art generally had a significantly different function and is never identical with the modern straight-arm salute.[1]

The right hand (Lat. dextera, dextra; Gr. δεξιά - dexia) was commonly used in antiquity as a symbol of pledging trust, friendship or loyalty.[4] For example, Cicero reported that Octavian pledged an oath to Julius Caesar while outstretching his right hand: "Although that youth [the young Caesar Octavian] is powerful and has told Antony off nicely: yet, after all, we must wait to see the end. But what a speech! He swore his oath with the words: 'so may I achieve the honours of my father!', and at the same time he stretched out his right hand in the direction of his statue."[5]

Sculptures commemorating military victories such as those on the Arch of Titus, the Arch of Constantine, or on the Column of Trajan are the best known examples of raised arms in art from this period.[6] However these monuments do not display a single clear image of the Roman salute.[6]

The images closest in appearance to a raised arm salute are scenes in Roman sculpture and coins which show an adlocutio, acclamatio, adventus, or profectio.[7] These are occasions when a high-ranking official, such as a general or the Emperor, addresses individuals or a group, often soldiers. Unlike modern custom, in which both the leader and the people he addresses raise their arms, most of these scenes show only the senior official raising his hand.[8] Occasionally it is a sign of greeting or benevolence, but usually it is used as an indication of power.[8] An opposite depiction is the salutatio of a diogmites, a military police officer, who raises his right arm to greet his commander during his adventus on a relief from 2nd-century Ephesus.[9]

An example of a salutational gesture of imperial power can be seen in the statue of Augustus of Prima Porta which follows certain guidelines set out by oratory scholars of his day.[10] In Rhetorica ad Herennium the anonymous author states that the orator "will control himself in the entire frame of his body and in the manly angle of his flanks, with the extension of the arm in the impassioned moments of speech, and by drawing in the arm in relaxed moods".[10] Quintilian states in his Institutio Oratoria: "Experts do not permit the hand to be raised above the level of the eyes or lowered beneath the breast; to such a degree is this true that it is considered a fault to direct the hand above the head or lower it to the lower part of the belly. It may be extended to the left within the limits of the shoulder, but beyond that it is not fitting."[10]

18th–19th centuries France

Beginning with Jacques-Louis David's painting The Oath of the Horatii (1784), an association of the gesture with Roman republican and imperial culture emerged.[11][12] The painting shows the three sons of Horatius swear on their swords, held by their father, that they will defend Rome to the death.[13] It is based on a historical event described by Livy (Book I, sections 24-6) and elaborated by Dionysius in Roman Antiquities (Book III).[14] However, the moment depicted in David's painting is his own creation.[15] Neither Livy nor Dionysius mention any oath taking episode.[13] Dionysius, the more detailed source, reports that the father had left to his sons the decision to fight then raised his hands to the heavens to thank the gods.[15]

Dominating the center of The Oath of the Horatii is the brothers' father, facing left. He has both hands raised.[15] His left hand is holding three swords, while his right hand is empty, with fingers stretched but not touching.[15] The brother closest to the viewer is holding his arm almost horizontally.[15] The brother on the left is holding his arm slightly higher, while the third brother holds his hand higher still.[15] While the first brother extends his right arm, the other two are extending their left arms. The succession of arms raised progressively higher leads to a gesture closely approximating the style used by fascists in the 20th century in Italy, albeit with the "wrong" arms.[15]

Art historian Albert Boime provides the following analysis:

The brothers stretch out their arms in a salute that has since become associated with tyranny. The "Hail Caesar" of antiquity (although at the time of the Horatii a Caesar had yet to be born) was transformed into the "Heil Hitler" of the modern period. The fraternal intimacy brought about by the Horatii's dedication to absolute principles of victory or death ... is closely related to the establishment of the fraternal order ... In the total commitment or blind obedience of a single, exclusive group lies the potentiality of the authoritarian state.[12]

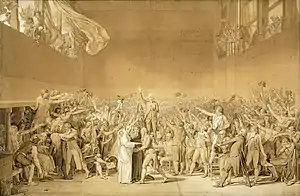

After the French Revolution of 1789, David was commissioned to depict the formation of the revolutionary government in a similar style. In the Tennis Court Oath (1792) the National Assembly are all depicted with their arms outstretched, united in an upward gesture comparable to that of the Horatii, as they swear to create a new constitution.[16] The painting was never finished, but an immense drawing was exhibited in 1791 alongside the Oath of the Horatii.[12] As in the Oath of the Horatii, David conveys the unity of minds and bodies in the service of the patriotic ideal.[12] But in this drawing, he takes the subject further, uniting the people beyond just family ties and across different classes, religions, and philosophical opinions.[12]

_01.jpg.webp)

After the republican government was replaced by Napoleon's imperial régime, David further deployed the gesture in The Distribution of the Eagle Standards (1810).[17] But unlike his previous paintings representing republican ideals, in Eagle Standards the oath of allegiance is pledged to a central authority figure, and in imperial fashion.[17] Boime sees the series of oath pictures as "the coding of key developments in the history of the Revolution and its culmination in Napoleonic authoritarianism".[18]

The imperial oath is seen in other paintings, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme's Ave Caesar! Morituri te salutant (Hail, Caesar, those who are about to die salute you) of 1859.[19] In this painting, the gladiators are all raising their right or left arms, holding tridents and other weapons.[19] Their salutation is a well-known Latin phrase quoted in Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum ("The Life of the Caesars", or "The Twelve Caesars").[20] Despite becoming widely popularised in later times, the phrase is unknown in Roman history aside from this isolated use, and it is questionable whether it was ever a customary salute, as is often believed.[21] It was more likely to be an isolated appeal by desperate captives and criminals condemned to die.[22]

19th–20th centuries United States

On October 12, 1892, the Bellamy salute was demonstrated as the hand gesture to accompany the Pledge of Allegiance in the United States. The inventor of the saluting gesture was James B. Upham, junior partner and editor of The Youth's Companion.[23] Bellamy recalled Upham, upon reading the pledge, came into the posture of the salute, snapped his heels together, and said "Now up there is the flag; I come to salute; as I say 'I pledge allegiance to my flag,' I stretch out my right hand and keep it raised while I say the stirring words that follow."[23]

As fascism took hold in Europe, controversy grew on the use of the Bellamy salute given its similarity to the Roman Salute. When war broke out in 1939, the controversy intensified. School boards around the country revised the salute to avoid the similarity. There was a counter-backlash from the United States Flag Association and the Daughters of the American Revolution, who felt it inappropriate for Americans to have to change the traditional salute because aliens had later adopted a similar gesture.[24]

On June 22, 1942, at the urging of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Congress passed Public Law 77-623, which codified the etiquette used to display and pledge allegiance to the flag. This included use of the Bellamy salute, specifically that the pledge "be rendered by standing with the right hand over the heart; extending the right hand, palm upward, toward the flag at the words ‘‘to the flag’’ and holding this position until the end, when the hand drops to the side." Congress did not discuss or take into account the controversy over use of the salute. Congress later amended the code on December 22, 1942 when it passed Public Law 77-829. Among other changes, it eliminated the Bellamy salute and replaced it with the stipulation that the pledge "be rendered by standing with the right hand over the heart."[25]

Early 20th century in theatre and film

The gesture, already established in the United States through the Bellamy salute, has been traced to the Broadway production of the play Ben-Hur.[26] The play, based on Lew Wallace's book Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, opened on Broadway in November 1899 and proved to be a great success.[27] Photographs show several scenes using the gesture, including one of Ben-Hur greeting a seated sheik and another of a small crowd so greeting Ben-Hur in his chariot.[28] Neither Wallace's novel nor text for the theatrical production mentions a raised arm salute.[28] The salute was evidently added in keeping with the exaggerated style of acting in 19th century theater, which in turn influenced acting in the silent cinema.[29]

The salute frequently occurs in early 20th century films set in antiquity, such as the American Ben-Hur (1907) and the Italian Nerone (1908), although such films do not yet standardize it or make it exclusively Roman.[30] In Spartaco (1914), even the slave Spartacus uses it.[30] Later examples appear in Ben-Hur (1925) and in Cecil B. DeMille's Sign of the Cross (1932) and Cleopatra (1934), although the execution of the gesture is still variable.[30]

Of special note is the use in Giovanni Pastrone's colossal epic Cabiria (1914).[31] Its intertitles, character names, and movie title were attributed to Italian nationalist Gabriele d'Annunzio, who was known as the "poet-warrior".[32] Inspired by the Italo-Turkish War, in which Italy conquered the North African Ottoman province of Tripolitania, Pastrone perused a politically volatile issue.[33] The film highlights Italy's Roman past and the "monstrous" nature of Carthaginian society, which is contrasted with the "nobility" of Roman society.[34] Cabiria was one of several films of the period that "helped resuscitate a distant history that legitimized Italy's past and inspired its dreams" and which "delivered the spirit for conquest that seemed to arrive from the distant past", thereby presaging the "political rituals of fascism", "thanks ... to its prime supporter and apostle, Gabriele d'Annunzio."[35]

Variations on the salute occur throughout Cabiria on the part of Romans and Africans.[36] Scipio uses the gesture once.[36] Fulvius Axilla, the story's fictitious hero, twice employs it as a farewell greeting to his hosts.[36] The Numidian king Massinissa, guest of the Carthaginian Hasdrubal, raises his right hand and is so greeted in return, once by the strongman Maciste.[36] Princess Sophonisba and King Syphax mutually greet each other by raising their hands and declining their bodies.[36] The diversity of the gesture and the variety of nationalities who use it in Cabria is seen as further evidence that the salute is a modern invention, used in the film to highlight the exotic nature of antiquity.[36]

Adoption during the 20th century

Italy

D'Annunzio, who had written the subtitles for the silent movie epic Cabiria, appropriated the salute when he occupied Fiume in 1919.[37] D'Annunzio has been described as the John the Baptist of Italian Fascism,[38] as virtually the entire ritual of Fascism was invented by D'Annunzio during his occupation of Fiume and his leadership of the "Italian Regency of Carnaro".[39] Besides the Roman salute, these included the balcony address, the cries of "Eia, eia, eia! Alalà!", the dramatic and rhetorical dialogues with the crowd, and the use of religious symbols in new secular settings.[38]

Like other neo-Imperial rituals utilized by D'Annunzio, the salute became part of the Italian fascist movement's symbolic repertoire.[37] On January 31, 1923, the Ministry of Education instituted a ritual honoring the flag in schools using the Roman salute.[37] In 1925, as Mussolini began his fascitization of the state, the salute was gradually adopted by the regime, and by December 1, 1925 all state civil administrators were required to use it.[37]

Achille Starace, the Italian Fascist Party secretary, pushed for measures to make the use of the Roman salute generally compulsory, denouncing hand shaking as bourgeois. He further extolled the salute as "more hygienic, more aesthetic, and shorter." He also suggested that the Roman salute did not imply the necessity of taking off the hat unless one was indoors. By 1932, the salute was adopted as the substitute for the handshake.[37] On August 19, 1933 the military was ordered to use the salute whenever an unarmed detachment of soldiers was called on to render military honors for the King or Mussolini.[40]

The symbolic value of the gesture grew, and it was felt that the proper salute "had the effect of showing the fascist man's decisive spirit, which was close to that of ancient Rome".[41] The salute was seen to demonstrate the fascist's "decisive spirit, firmness, seriousness, and acknowledgment and acceptance of the regime's hierarchical structure".[42] It was further felt that the correct physical gesture brought forth a change in character.[43] A joke claimed, however, that the Fascist salute used one hand because Italians were tired of raising both hands to surrender during World War I.[44]

The bourgeois gesture was supposed to disappear from the view of Italians and not contaminate their daily life. In 1938, the party abolished handshaking in films and theater, and on November 21, 1938 the Ministry of Popular Culture issued orders banning the publishing of photographs showing people shaking hands. Even official photographs of visiting dignitaries were retouched to remove the image of their handshaking.[43]

Germany

In Germany, the salute, sporadically used by the Nazi Party (NSDAP) since 1923, was made compulsory within the movement in 1926.[45] Called the Hitler salute (Hitlergruß), it functioned both as an expression of commitment within the party and as a demonstrative statement to the outside world.[46] Yet in spite of this demand for the outward display of obedience, the drive to gain acceptance did not go unchallenged, even within the movement.[46] Early objections focused on its resemblance to the Roman salute employed by Fascist Italy, and hence on it not being Germanic.[46] In response, efforts were made to establish its pedigree and invent a proper tradition after the fact.[46]

The compulsory use of the Hitler salute for all public employees followed a directive issued by Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick on July 13, 1933, one day before the ban on all non-Nazi parties.[47] The Wehrmacht refused to adopt the Hitler salute and was able for a time to maintain its own customs.[48] The military were required to use the Hitler salute only while singing the Horst Wessel Lied and German national anthem, and in non-military encounters such as greeting members of the civilian government.[48] Only after the July 20 Plot in 1944 were the military forces of the Third Reich ordered to replace the standard military salute with the Hitler salute.[49]

Elsewhere

Similar forms of salutes were adopted by various groups. Its use in France dates back to 1925, when the Jeunesses Patriotes (Patriotic Youth), a movement led by Pierre Taittinger, would give the fascist salute at meetings while shouting "Dictatorship!".[50] Marcel Bucard's Mouvement Franciste, founded in September 1933, adopted the salute as well as donning blue shirts and blue berets.[51] Solidarité Française used the salute as well, though its leaders denied the movement was fascist.[52] By 1937, rivalry amongst French right wing parties sometimes caused confusion over salutes.[53] The Parti Populaire Français, generally regarded as the most pro-Nazi of France's collaborationist parties, adopted a variant of the salute that distinguished itself from others by slightly bending the hand and holding it at face level.[54]

In the early 1930s, the salute was used by members of the Estonian nationalist right wing Vaps Movement,[55] as well as the Brazilian Integralist Action, who used to salute by raising one arm. The Brazilian form of the Salute was called "Anauê" – a word used as a salutation and as a cry by the Brazilian indigenous Tupi people, meaning "you are my brother".[56]

In Greece in 1936, when Ioannis Metaxas and his 4th of August Regime took power, an almost identical salute was adopted – first by the National Youth Organization and later by the government as well as common people – and used even while fighting against Italy and Germany in WW2.

In Spain, on April 27, 1937, General Francisco Franco formally approved the salute in a decree which made it the official salutation to be used by all except the military, who would continue to use the traditional military salutes.[57] This was repealed in September 1945.[58] When the Franco regime restored "Marcha Real" as the Spanish national anthem in 1942 and established unofficial new lyrics for it, the first stanza referred to the fascist salute: "Alzad los brazos, hijos del pueblo español" ("Raise your arms, sons of the Spanish people"). These lyrics remained part of the Spanish national anthem until 1978.[59]

After a meeting with Mussolini, in December 1937, Yugoslav Prime Minister Milan Stojadinović and chairman of Yugoslav Radical Union adopted a version of the salute as he took to styling himself as Vođa (Leader).[60][61]

On January 4, 1939, the salute by raising one arm was adopted in Romania under a statute promulgating the National Renaissance Front.[62] In Slovakia, the Hlinka Guard's Na stráž! (On guard!) consisted of a half-hearted compromise between a friendly wave and a salute with a straight raised arm.[63]

Post World War II

Italy

The salute has been used many times by prominent individuals as well as groups of people since the war. Famed poet Ezra Pound used the salute in praise of his adopted country of Italy when he returned in 1958 after being released from an insane asylum in America.[64] The salute was on display in the 1968 funeral for Mussolini's youngest daughter, Anna Maria Mussolini Negri.[65] When the Italian Social Movement had its greatest electoral gains since the Second World War in June, 1971, crowds at the party headquarters cheered and gave the outstretched arm salute.[66] On July 29, 1983, on the 100th anniversary of Mussolini's birth, thousands of black-shirted supporters chanted "Duce! Duce!" with their arms raised in the fascist salute on a march from his native village of Predappio in Romagna to the cemetery where he was buried.[67] On the eve of Silvio Berlusconi's election victory in 1994, young supporters of Gianfranco Fini made the fascist salute while chanting "Duce! Duce!"[68]

In 2005, Italian footballer Paolo Di Canio created controversy by twice using the gesture to salute S.S. Lazio fans, first in a match against archrivals A.S. Roma and then against A.S. Livorno Calcio (a club inclined to leftist politics).[69] Di Canio received a one match game ban after the second event and was fined 7,000 euros, after which he was quoted as saying "I will always salute as I did because it gives me a sense of belonging to my people [...] I saluted my people with what for me is a sign of belonging to a group that holds true values, values of civility against the standardisation that this society imposes upon us."[70] His salute featured on unofficial merchandise sold outside Stadio Olimpico after the ban.[69] Di Canio has also expressed admiration for Mussolini.[71][72]

In June, 2009, Michela Vittoria Brambilla, an Italian politician and businesswoman commonly described as a possible successor to Silvio Berlusconi for leadership of the Italian right, was caught in a controversy over her alleged use of the Roman salute, with calls for her to step down.[73] She denied the accusation, stating "I've never either done or thought of doing any gesture that is an apology of fascism, something toward which I've never showed any indulgence, let alone sympathy. And why should I have made a public display of such a despicable gesture shortly after I've been made a minister?"[73] A video of the event was posted on the Web site of the newspaper La Repubblica that showed Brambilla extending her right arm upward in what appears to be a fascist salute.[73] Brambilla said she was just greeting the crowd.[73]

Germany

Use of the salute and accompanying phrases has been forbidden by law in Germany since the end of World War II. Section 86a of the German Penal Code provides for punishment of up to three years in prison for anyone using the salute, unless it is used for artistic, scientific, or educational purposes.[74]

Greece

The Greek nationalist party Golden Dawn uses the Roman salute unofficially. Golden Dawn is accused by its opponents of being neo-Nazi, but the party denies this and claims that the salute is ancient Greek or Roman, and that it is used as a tribute to Ioannis Metaxas and his 4th of August Regime which led Greece against the foreign occupation forces in WWII.[75][76][77][78][79][80][81]

The Levant

The salute employed by certain groups and their supporters, like Hezbollah, Fatah,[82] pro-Assad NDF[83] and Assad supporters,[84] the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, and the Kataeb Party,[85] have often been confused with the Roman/Nazi salute, even though in many cases the salute is performed by a closed fist rather than the Roman/Nazi extended palm. Opposition fighters in Syria have also been filmed and documenting using it, or a variance thereof, on multiple occasions.[86] From its use, a connection between Nazism and these groups is often alleged . Often these allegations are raised at the expense of the opposing groups, pro-Assad sympathizers alleging Nazi sympathies of the Opposition and vice versa.[86] However, the oath of allegiance by the Lebanese army, and the salute to the flag uses the Roman salute - possibly influenced by Vichy France shortly before independence was officially gained in 1944 - still continues to be used by the state today.[87]

Portugal

In Portugal the salute is still used today by the military to take their oath to the national flag, when they successfully complete the first phase of military instruction. Formed in front of the highest symbol of national sovereignty, the military in sense and attunement, raise their right arm pointed towards the flag and take their oath.[88]

South Africa

The Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging, a neo-Nazi political party and paramilitary force known for its advocacy of an all-white Afrikaner Volkstaat,[89][90] has utilized Nazi-style uniforms, flags, insignia, and salutes at meetings and public rallies.[91] Hundreds of supporters in 2010 delivered straight-arm salutes outside the funeral for its founder and former leader Eugène Terre'Blanche, who was murdered by two black farm workers over an alleged wage dispute.[92][93]

Red Hand of Ulster Salute

The Red Hand of Ulster Salute is a modified version of the Roman Salute in which the hand is raised vertically to symbolise the Red Hand of Ulster. It is used by some Rangers F.C. fans to show an affinity with the Loyalist cause. Its similarity to the Nazi salute has caused offence and the football club and its supporters' association have asked them not to use it. [94] [95]

Popular culture

A large number of films made after World War II made the Roman salute a visual stereotype of a proto-fascist ancient Roman society.[96] In the 1951 film Quo Vadis, Nero's repeated use of the salute at mass rallies explicitly presents the Roman Empire as a Fascist military state.[97] The movie provided other filmmakers of the time a model,[96] with notable examples including Ben-Hur,[98] Spartacus,[99] Cleopatra,[100] and Caligula. Not until Gladiator did the Roman epic return to the cinema.[101] In this movie, the salute is notably absent in most scenes, for example when Commodus enters Rome or when the Senate salutes the Emperor by head-bowing.[101]

Variations on the salute also appear in neo-fascist contexts. For example, The Christian Falangist Party, founded in 1985, uses a "pectoral salute", in which the right arm, bent at the elbow, is extended from the heart, palm down.[102] This gesture was used in François Truffaut's 1966 film Fahrenheit 451.[103] The film portrays a futuristic totalitarian society modeled after the fascist state, including black uniforms, book burnings, and thought control.[103] In the Star Trek episode "Mirror, Mirror", the salute begins with the right fist being placed over the heart, as in a pectoral salute, and then the arm is stretched out (usually up) before the body, open palm down, as in a traditional Roman salute.[104] In the episode, Captain Kirk and members of his crew are transported to a parallel universe in which the United Federation of Planets has been replaced by an empire characterized by sadistic violence and torture, genocide, and unquestioning obedience to authority.[104] A modified Roman salute is commonly used in the British-American series Rome.[105] Here the salute avoids similarity to the Fascist salute, as the series seeks not to depict these Romans as stereotypical conquerors.[105] Therefore, the salute is not the familiar straight arm salute but rather resembles a pectoral salute, with the right hand is placed over the heart and then extended to the front of the body.[105]

See also

References

Citations

- Winkler (2009), p. 2

- Since the historicity of the salute has never been properly questioned, performing it is prosecutable only when "meant to exalt exponents, principles, events and methods" of the extinct National Fascist Party.

- "Saluto fascista, la Cassazione: "Non è reato se commemorativo" e conferma due assoluzioni a Milano" [Fascist salute, Supreme Court of Cassation: "Not a crime if memorial" and confirms two acquittals in Milan]. La Repubblica (in Italian). Milan. February 20, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- K.E. Georges, Ausführliches lateinisch-deutsches Handwörterbuch, Leipzig, Hahn'sche Verlags-buchhandlung Lateinisch-deutscher theil. 1879–80. 2 v.--Deutsch-lateinischer theil 1882 2 v (reprint Berlin 2007), s.v. "dexter"; cf. Lewis-Short s.v. "dextera"; cf. LSJ s.v. "δεξιά".

- It is unknown if Octavian's specific oath salute was a pre-existing Roman custom or if he modified a similar pledging gesture for his contio, but Cicero clearly disapproved of Octavian's performance, exclaiming: "I don't want to be saved by such a man"; cf. Cic. Att. 16.15.3.6: Quamquam enim †postea† in praesentia belle iste puer retundit Antonium, tamen exitum exspectare debemus. at quae contio! nam est missa mihi. iurat "ita sibi parentis honores consequi liceat" et simul dextram intendit ad statuam. μηδὲ σωθείην ὐπό γε τοιούτου! [Nec servatoribus istis!]

- Winkler (2009), pp. 17

- Winkler (2009), p. 20

- Winkler (2009), pp. 20–21

- Probably as an acclamatio; note palm is perpendicular to the ground and thumb is sticking up cf. Graham Sumner, Roman military clothing: 100 BC – AD 200, Oxford 2002, p. 47, pl. G3 (Diogmitoi [sic! correct plural: diogmitai]).

- Moon, Warren G. (1995). Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and tradition. Wisconsin studies in classics (illustrated ed.). Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 271–272. ISBN 978-0-299-14310-7.

- Winkler (2009), p. 55 The raised arm, first stretched out as a symbol of righteous fervor-as the Horatii evince it-and later as a symbol of political allegiance and religious-political unity between a people and its leader, becomes an important part of the iconography of new societies. In addition to its specific contemporary use the gesture comes to express, in a fashion that appears timeless and even mystical, an appeal to a higher being and to a heroic ancient past that had served as a model for most of Western civilization for centuries, although often in ways not supported by historical fact. David’s Oath of the Horatii provided the starting point for an arresting gesture that progressed from oath-taking to what will become known as the Roman salute.

- Boime, Albert (1987). Art in an age of revolution, 1750–1800. Social history of modern art. Volume 1. University of Chicago Press. pp. 400–401. ISBN 978-0-226-06334-8.

- Roth, Michael (1994). "Facing the Patriarch in Early Davidian Painting". Rediscovering history: culture, politics, and the psyche. Stanford University Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-8047-2313-8.

- Marvin, Roberta Montemorra; Downing A. Thomas (2006). "Roman Republicanism and Operatic Heroines". Operatic migrations: transforming works and crossing boundaries (illustrated ed.). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-7546-5098-0.

- Winkler (2009), p. 44

- Parker (1990), p. 87

- Winkler (2009), p. 51

- Boime, Albert (1993). Art in an age of Bonapartism, 1800–1815. Social history of modern art. 2 (reprint, illustrated ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 46.

- Winkler (2009), p. 40

- Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum: Divus Claudius, 21.6

- Baker, Alan (2000). The gladiator: the secret history of Rome's warrior slaves. Ebury Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-09-187880-1.

- Kyle, Donald (2001). Spectacles of death in ancient Rome. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-415-24842-6.

- Miller, Margarette S. (1976). Twenty Three Words: A Biography of Francis Bellamy: Author of the Pledge of Allegiance. Natl Bellamy Award. ISBN 978-0-686-15626-0.

- Ellis, Richard (2005). To the Flag: The Unlikely History of the Pledge of Allegiance (illustrated ed.). University Press of Kansas. pp. 113–116.

- Ellis, Richard (2005). To the Flag: The Unlikely History of the Pledge of Allegiance (illustrated ed.). University Press of Kansas. pp. 116–118.

- Winkler (2009), p. 70

- Winkler (2009), p. 71

- Winkler (2009), p. 73

- Winkler (2009), p. 75

- Winkler, Martin. "The Roman Salute on Film". 2003 APA Annual Meeting. The American Philological Association (APA) (January 8, 2003).

- Winkler (2009), pp. 94–95

- Leeden (2001), p. 67

- Solomon, Jon (2001). The ancient world in the cinema (2, revised, illustrated ed.). Yale University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-300-08337-8.

- Wood, Mary P. (2005). Italian cinema. Berg Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-84520-162-3.

- Brunetta, Gian Piero; Jeremy Parzen (2009). The History of Italian Cinema: A Guide to Italian Film from Its Origins to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-691-11988-5.

- Winkler (2009), p. 99

- Falasca-Zamponi (2000), p. 110

- Leeden (2001), p. xiii

- Paxton, Robert O. (2005). "Taking Root". The Anatomy of Fascism. Vintage Series (reprint ed.). Random House, Inc. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-1-4000-3391-1.

- Wireless (August 20, 1933). "Fascist Salute Is Adopted By Italian Armed Forces". The New York Times. p. Page 1. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- Falasca-Zamponi (2000), pp. 110–111

- Falasca-Zamponi (2000), pp. 112–113

- Falasca-Zamponi110 (2000), pp. 113

- Gunther, John (1936). Inside Europe. Harper & Brothers. p. 183.

- Kershaw (2001), p. 26

- Tilman (2009), p. 55

- Kershaw (2001), p. 60

- Tilman (2009), pp. 80–82

- Tilman (2009), p. 82

- Soucy (1997), p. 40

- Soucy (1997), p. 38–39

- Soucy (1997), p. 71

- Soucy (1997), p. 142

- Soucy (1997), p. 217

- Kasekamp, Andres (June 3, 2000). The Radical Right in Interwar Estonia - Andres Kasekamp - Google Boeken. ISBN 9780312225988. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- Payne, Stanley (1995). "Fascism outside Europe?". A history of fascism, 1914–1945 (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 345. ISBN 978-1-85728-595-6.

- "Fascist Salute Adopted". The Montreal Gazette. April 27, 1937. p. 10. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- Decreto de la Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros derogando la obligatoriedad del saludo brazo en alto, de fecha 11 de septiembre de 1945, publicado en el B.O.E. núm, 257 con fecha 14 de septiembre de 1945.

- Elkington, Mark (January 16, 2008). "Divisive national anthem lyrics ditched". Reuters. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). "The kingdom of Yugoslavia". A short history of the Yugoslav peoples (2, illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Benson, Leslie (2001). "Destruction of the First Yugoslavia". Yugoslavia: a concise history (illustrated ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-333-79241-4.

- Webb, Adrian (2008). "The Rise of Authoritianism 1919–1939". The Routledge companion to Central and Eastern Europe since 1919. Routledge companions to history. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-203-92817-2.

- Jelinek, Yeshayahu (1971). "Storm-Troopers in Slovakia: The Rodobrana and the Hlinka Guard". Journal of Contemporary History. Sage Publications. 6 (3): 104. doi:10.1177/002200947100600307. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 259881. OCLC 49976309. S2CID 159713369.

- "Pound, in Italy, Gives Fascist Salute; Calls United States an 'Insane Asylum'". The New York Times. July 10, 1958. p. 56. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- "Mussolini's Followers Mourn Death of His Daughter". The New York Times. April 27, 1968. p. 8. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- UPI (June 16, 1971). "Fascists Make Gains In Italian Elections". Montreal Gazette. p. 5. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- "Thousands Give Fascist Salute At Rally To Honor Mussolini". Montreal Gazette. July 30, 1983. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- COWELL, ALAN (March 31, 1994). "Italy's Neo-Fascists: Have They Shed Their Past?". The New York Times. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- Kassimeris, Christos (2008). European football in black and white: tackling racism in football. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7391-1960-0.

- Nursey, James (December 19, 2005). "Football: ll Di Canio new salute row". The Daily Mirror; London (UK). Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- Duff, Mark (January 9, 2005). "Footballer's 'fascist salute' row". BBC News. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- Fenton, Ben (December 24, 2005). "I'm a fascist, not a racist, says Paolo di Canio". Telegraph. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- AP foreign (June 17, 2009). "Italy official in row over apparent fascist salute". The Guardian. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- Tilman (2009), p. 94–95

- "Ο ναζιστικός χαιρετισμός του αρχηγού της Χρυσής Αυγής". Madata.GR. October 9, 2008. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Τα παιδιά του Χίτλερ με στολή "Χρυσής Αυγής"". Ethnos. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Ναζιστικός χαιρετισμός στο Δημοτικό Συμβούλιο της Λαμίας". tvxs.gr. April 11, 2012.

- "Επιμένει στον ναζιστικό χαιρετισμό η Χρυσή Αυγή". To Vima. October 22, 2012.

- Kyriakidou, Dina. "Special Report: Greece's far-right party goes on the offensive". Reuters. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Far-right Golden Dawn goes on the offensive in Greece". ekathimerini.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Golden Dawn chief admits his party uses "nazi salute" and demonstrates it with a gesture". Keeptalkinggreece.com. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Theblaze.com". Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- YouTube

- Yourmiddleeast.com

- Thearabdigest.com Archived December 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Rocklandtimes.com

- "Timeframe 0:06 - 0:07". Lebanese Army.

- https://academiamilitar.pt/juramento-de-bandeira-2019.html

- "Separation, even after apartheid; Many whites fear for life after Mandela," (21 June 2013) National Post, Ontario

- "Extremists Steal Guns for S. Africa War" (May 30, 1990), Elyria Chronicle Telegram

- "Eugene Terre'Blanche's Afrikaner Resistance Movement - Rally," youtube. See 0:40 for salutes.

- "AWB leader Eugene Terreblanche's funeral in Ventersdorp, South Africa, in pictures". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- "South African white supremacist Eugene Terreblanche laid to rest". The Telegraph. April 9, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- "Uefa drops Rangers salute probe". BBC News. February 21, 2007.

- "Outrage at 'Nazi salutes' by soldiers in front of Union Flag". Herald Scotland. October 28, 2013.

- Winkler (2009), p. 151

- Winkler (2009), p. 143–145

- Winkler (2009), p. 155

- Winkler (2009), p.158

- Winkler (2009), p. 159

- Winkler (2009), p. 164

- Winkler (2009), p. 6

- Winkler (2009), p. 176

- Winkler (2009), p. 169

- Winkler (2009), p. 174

Bibliography

- Allert, Tilman; Translated by Jefferson Chase (April 2009). The Hitler Salute: On the Meaning of a Gesture (Picador ed.). Picador. ISBN 978-0-312-42830-3.

- Falasca-Zamponi, Simonetta (2000). Fascist spectacle: the aesthetics of power in Mussolini's Italy. Studies on the history of society and culture. 28 (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22677-7.

- Kershaw, Ian (2001). The "Hitler myth": Image and reality in the Third Reich (2, reissue ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280206-4.

- Ledeen, Michael Arthur (2001). D'Annunzio: the first duce (2, illustrated ed.). Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0742-7.

- Parker, Noel (1990). Portrayals of revolution: images, debates, and patterns of thought on the French Revolution (illustrated ed.). SIU Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-1684-7.

- Soucy, Robert (1997). French Fascism: The Second Wave, 1933–1939 (illustrated ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07043-9.

- Winkler, Martin M. (2009). The Roman Salute: Cinema, History, Ideology. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-0864-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman salutes. |

- President of Republic of China (Taiwan) Ma Ying Jeou giving Roman salute

- Former President of Republic of China (Taiwan) Chen Shui Bian giving Roman salute

- Officials in the Republic of China (Taiwan) being sworn in with Roman Salute

- Photograph and "cartoon view" explanation of Trajan's Column, from McMaster University Humanities department

- Droit, Jean. "Paris 1924 – Jeux Olympiques". From Olympic Games Museum. French Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010.. Poster from 1924 Olympics depicting Olympic salute