Rashidun army

The Rashidun army was the core of the Rashidun Caliphate's armed forces during the Muslim conquests of the 7th century, serving alongside the Rashidun navy. The Rashidun army maintained a high level of discipline, strategic prowess and organization.[1]

| Rashidun Army | |

|---|---|

| Active | 632–661 |

| Country | Rashidun Caliphate |

| Allegiance | Islam |

| Branch | Army |

| Headquarters | Medina (632–657) Kufa (657–661) |

| Engagements | Muslim conquest of Persia Arab-Byzantine Wars Muslim conquest of Egypt Arab–Khazar wars Muslim conquest of Transoxiana Arab invasion of Sindh North African conquests |

| Commanders | |

| Supreme-Commander | Caliph Abu Bakr al-Siddiq Umar ibn al-Khattab |

| Notable Commanders | Khalid ibn Walid Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah Amr ibn al-'As |

In its time, the Rashidun army was a powerful and very effective force. The three most successful generals of the Rashidun army were Khalid ibn al-Walid, who conquered Persian Mesopotamia and Roman Syria, and Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah who conquered Roman Syria, and 'Amr ibn al-'As, who conquered Roman Egypt.

Army

Only Muslims were allowed to join the Rashidun army as regular soldiers. During the Ridda wars in the reign of Caliph Abu Bakr, the army mainly consisted of the corps from Medina, Mecca and Taif. Later on during the conquest of Iraq in 633 many bedouin corps were recruited as regular soldiers. During the Islamic conquest of Sassanid Persia (633-656), some 12,000 elite Persian soldiers converted to Islam and served later on during the invasion of the empire. During the Muslim conquest of Roman Syria (633-638,) some 4,000 Greek Byzantine soldiers under their commander Joachim (later Abdullah Joachim) converted to Islam and served as regular troops in the conquest of both Anatolia and Egypt. During the conquest of Egypt (641-644), Coptic converts to Islam were recruited. During the conquest of North Africa, Berber converts to Islam were recruited as regular troops, who later made the bulk of the Rashidun army and later the Umayyad army in Africa.

Infantry

Rashidun army relied heavily on their infantry. The infantry, rather than cavalry, was the bulk of the army and its most important component.[2] Mubarizun were a special part of the Muslim army, composed of the champions. Their role was to undermine the enemy morale by slaying their champions. The infantry would make repeated charges and withdrawals known as karr wa farr, using spears and swords combined with arrow volleys to weaken the enemies and wear them out. However, the main energy had to still be conserved for a counterattack, supported by a cavalry charge, that would make flanking or encircling movements. Defensively, the Muslim spearman with their two and a half meter long spears would close ranks, forming a protective wall (Tabi'a) for archers to continue their fire. This close formation stood its ground remarkably well in the first four days of defence in the Battle of Yarmouk.[3]

Cavalry

The Rashidun cavalry was one of the most successful light cavalry forces, provided it was competently led. It was armed with lances and swords. Initially, the cavalry was used as a reserve force, with its main role being to attack the enemy once they were weakened by the repeated charges of the infantry. The cavalry would then make flanking or encircling movements against the enemy army, either from the flanks or straight from the center, most likely using a wedge-shaped formation in its attack. Some of the best examples of the use of the cavalry force occurred under the command of Khalid ibn Walid in the Battle of Walaja against the Sassanid Persians and in the Battle of Yarmouk against the Byzantines. In both cases the cavalry regiments were initially stationed behind the flanks and center. The proportion of cavalry within the Rashidun forces were initially limited to less than 20% due to the inability of the poor economic condition and arid climate of the Arabian Peninsula to support large numbers of warhorses. As the wealthy lands of the Near East were conquered, many Arab warriors acquired horses as booty or tribute, so that by the end of the Rashidun period half of the "Jund" forces were composed of cavalry. Mounted archery was initially not used by the Rashidun cavalry unlike their Byzantine and Persian opponents, this not being a traditional Arab fighting method. As the conquest of Persia progressed, some Sassanid gentry converted into Islam and joined the Rashidun cause; these "Asawira" were very highly regarded due to their skill as heavy cavalrymen as well as mounted archers.

Weaponry

Reconstructing the military equipment of early Muslim armies is problematic. Compared with Roman armies—or, indeed, later medieval Muslim armies—the range of visual representation is very small, often imprecise and difficult to date. Physically very little material evidence has survived and again, much of it is difficult to date.[4]

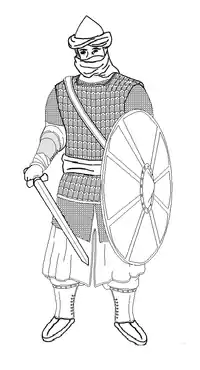

Helmets

Muslim headgear included gilded helmets—both pointed and rounded—similar to that of the silver helmets of the Sassanid Empire. The rounded helmet, referred to as ‘’Baidah’’ ("Egg"), was a standard early Byzantine type composed of two pieces. The pointed helmet was a segmented Central Asian type known as ‘’Tarikah’’. Mail armour was commonly used to protect the face and neck, either as an aventail from the helmet or as a mail coif the way it had been used by Romano-Byzantine armies since 5th century. The face was often half covered with the tail of a turban that also served as protection against the strong desert winds.

Armour

Hardened leather scale or lamellar armour was produced in Yemen, Iraq and along the Persian gulf coast. Mail armour was preferred and became more common later during the conquest of neighbouring empires, often being captured as part of the booty. It was known as Dir, and was opened part-way down the chest. To avoid rusting it was polished and stored in a mixture of dust and oil.[5] Infantry soldiers were more heavily armoured than horsemen.

Shields

Large wooden or wickerwork shields were in use, but most shields were made of leather. For this purpose, the hides of camels and cows was used and it would be anointed, a practice since ancient Hebrew times.[6] During the invasion of the Levant, Byzantine soldiers extensively used elephant hide shields, which were probably captured and used by the Rashidun army.

Spears

Long spears were locally made with the reeds of the Persian gulf coast. The reeds were similar to that of bamboo.

Swords

The sword was the most prestigious weapon of the early Muslims. High quality swords were made in Yemen from Indian wootz steel.,[7] while inferior swords were made throughout Arabia. Both the short Arab swords (similar to the Roman gladius) and Sassanid long swords were used and Rashidun horsemen as well as foot soldiers were often described as carrying both at the same time. All swords hung from a baldric. Another personal weapon was the dagger, a weapon used only as a last resort.

Bows

Bows were locally made in various parts of Arabia; the most typical were the hijazi bows. It could be one piece of wood or two pieces joined together back to back. The maximum useful range of the traditional Arabian bow used to be about 150 meters. Early Muslim archers were infantry archers.

Siege weaponry

Catapults were used extensively in siege operations. Under Caliph Umar siege towers, called dababah were also employed. These wooden towers moved on wheels and were several stories tall. They were driven up to the foot of the besieged fortification and then the walls were pierced with a battering ram. Archers guarded the ram and the soldiers who moved it.[8]

Organization of army as a state department

Caliph Umar was the first Muslim ruler to organize the army as a state department. This reform was introduced in 637 AD A beginning was made with the Quraish and the Ansars and the system was gradually extended to the whole of Arabia and to Muslims of conquered lands. A register of all adults who could be called to war was prepared, and a scale of salaries was fixed. All registered men were liable for military service. They were divided into two categories, namely:

- Those who formed the regular standing army; and

- Those that lived in their homes, but were liable to be called to the colors whenever needed.

The pay was given in the beginning of the month of Muharram. The allowances were paid during the harvesting season. The armies of the Caliphs were mostly paid in cash salaries. In contrast to many post-Roman polities in Europe, grants of land, or rights to collect taxes directly from the people within one's grant of land, were of only minor importance. A major consequence of this was that the army directly depended on the state for its subsistence which, in turn, meant that the military had to control the state apparatus.[9]

Movement

When the army was on the march, it always halted on Fridays. When on march, the day's march was never allowed to be so long as to tire out the troops. The stages were selected with reference to the availability of water and other provisions. The advance was led by an advance guard consisting of a regiment or more. Then came the main body of the army, and this was followed by the women and children and the baggage loaded on camels. At the end of the column moved the rear guard. On long marches the horses were led; but if there was any danger of enemy interference on the march, the horses were mounted, and the cavalry thus formed would act either as the advance guard or the rearguard or move wide on a flank, depending on the direction from which the greatest danger loomed.

When on march the army was divided into:

- Muqaddima (مقدمة) - "the vanguard"

- Qalb (قلب) - "the center"

- Al-khalf (الخلف) - "the rear"

- Al-mu'akhira (المؤخرة) - "the rearguard"

Divisions in battle

The army was organized on the decimal system.[10]

On the battlefield the army was divided into sections. These sections were:

- Qalb (قلب) - "the center"

- Maymana (ميمنه) - "the right wing"

- Maysara (ميسرة) - "the left wing"

Each section was under a commander and was at a distance of about 150 meters from each other. Every tribal unit had its leader called arifs. In such units, there were commanders for each 10, 100 and 1,000 men, the latter-most corresponding to regiments. The grouping of regiments to form larger forces was flexible, varying with the situation. Arifs were grouped and each group was under a commander called amir al-ashar and amir al-ashars were under the command of a section commander, who were under the command of the commander in chief, amir al-jaysh.

Other components of the army were:

Intelligence and espionage

It was one of the most highly developed departments of the army which proved helpful in most of the campaigns. The espionage (جاسوسية) and intelligence services were first organised by Muslim general Khalid ibn Walid during his campaign to Iraq.[11] Later, when he was transferred to the Syrian front he organized the espionage department there as well.[12]

Strategy

The basic strategy of early Muslim armies setting out to conquer foreign land was to exploit every possible drawback of the enemy army in order to achieve victory with minimum losses as the Rashidun army, quality-wise and strength-wise, was sub-standard to the Sassanid Persian army and the Byzantine army. Khalid ibn Walid, the first Muslim general of the Rashidun Caliphate to conduct a conquest in foreign land, during his campaign against the Sassanid Persian Empire (Iraq 633 - 634) and Byzantine Empire (Syria 634 - 638) developed brilliant tactics that he used effectively against both the Sassanid army and the Byzantine army. The main drawback of the armies of Sassanid Persian Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire was their lack of mobility.[13] Khalid ibn Walid decided to use the mobility of his own army to exploit the lack thereof in the Sassanid army and Byzantine army. Later the same strategy was adopted by all other Muslim generals throughout the period of military expansion. Though only part of the Rashidun army was actual cavalry, the entire army was camel mounted for movement. Khalid ibn Walid and then later Muslim generals were also able to make use of the fine fighting quality of the Muslim soldiers, the bulk of whom were bedouins and adept in swordsmanship.

The Muslims' light cavalry during the later years of the Islamic conquest of Levant became the most powerful section of the army. The best use of this lightly armed and fast moving cavalry was revealed at the Battle of Yarmouk (636 A.D) in which Khalid ibn Walid, knowing the importance and ability of his cavalry, used them to turn the tables at every critical instance of the battle with their ability to engage and disengage and turn back and attack again from the flank or rear. A strong cavalry regiment was formed by Khalid ibn Walid which included the veterans of the campaign in Iraq and Syria. Early Muslim historians have given it the name Tulai'a Mutaharrika (طليعة متحركة), or the mobile guard. This was used as an advance guard and a strong striking force to route the opposing armies with its greater mobility that gave it an upper hand when maneuvering against any Byzantine army. With this mobile striking force, the conquest of Syria was made easy.[14]

Another remarkable strategy developed by Al-Muthanna and later followed by other Muslim generals was not moving far from the desert so long as there were opposing forces within striking distance of its rear. The idea was to fight the battles close to the desert, with safe escape routes open in case of defeat.[15] The desert was not only a haven of security into which the Sassanid army and Byzantine army would not venture, but also a region of free, fast movement in which their camel mounted troops could move easily and rapidly to any destination that they chose. Following this same strategy during the conquest of Iraq and Syria, Khalid ibn Walid did not engage his army deep into Iraq and Syria until the opposing army had lost its ability to threaten his routes to the desert. Another possible advantage of always keeping a desert at the rear was easy communication and reinforcement.

Once the Byzantines were weakened and the Sassanids effectively destroyed, the later Rashidun generals were free to use any strategy and tactics to overpower the opposing forces but they mainly relied on the mobility of their troops to prevent the concentration of enemy troops in large numbers.[13]

Conduct and ethics

The basic principle in the Qur'an for fighting is that other communities should be treated as one's own. Fighting is justified for legitimate self-defense, to aid other Muslims and after a violation of the terms of a treaty, but should be stopped if these circumstances cease to exist.[16][17][18][19] During his life, Muhammad gave various injunctions to his forces and adopted practices toward the conduct of war. The most important of these were summarized by Muhammad's companion, Abu Bakr, in the form of ten rules for the Rashidun army:[20]

Stop, O people, that I may give you ten rules for your guidance in the battlefield. Do not commit treachery or deviate from the right path. You must not mutilate dead bodies. Neither kill a child, nor a woman, nor an aged man. Bring no harm to the trees, nor burn them with fire, especially those which are fruitful. Slay not any of the enemy's flock, save for your food. You are likely to pass by people who have devoted their lives to monastic services; leave them alone.

These injunctions were honored by the second caliph, Umar, during whose reign (634–644) important Muslim conquests took place.[21] In addition, during the Battle of Siffin, the caliph Ali stated that Islam does not permit Muslims to stop the supply of water to their enemy.[22] In addition to the Rashidun Caliphs, hadiths attributed to Muhammad himself suggest that he stated the following regarding the Muslim conquest of Egypt:[23]

"You are going to enter Egypt a land where qirat (a money unit) is used. Be extremely good to them as they have with us close ties and marriage relationships."

"Be Righteous to Allah about the Copts."

Generals of Rashidun Caliphate

- Khalid ibn al-Walid

- Amr ibn al-As

- Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah

- Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas

- Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan

- Shurahbil ibn Hasana

- Al-Qa'qa' ibn Amr al-Tamimi

- Dhiraar bin Al-Azwar

- Asim ibn Amr al-Tamimi

- Abdallah ibn Amir

- Uqba ibn Nafi

- Iyad ibn Ghanm

- Abdallah ibn Sa'd

- Busr ibn Abi Artat

- Abu al-A'war

- Uthman ibn Abi al-As

- Abu Ubayd al-Thaqafi

- Ikrima ibn Abi Jahl

- Zubayr ibn al-Awam

- Hashim ibn Utba

- Al-Nu'man ibn Muqrin

- Al-Mughira

- Arfaja al-Bariqi

See also

References

- Britain and the Arabs: Contributors: JB Glubb - author. Publisher: Hodder and Staughton. Place of Publication: London. Publication Year: 1959. Page Number:34

- Christon I. Archer (2002). World History of Warfare. University of Nebraska. p. 129. ISBN 0803244231.

- Military History Online

- The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. Contributors: Hugh Kennedy - author. Publisher: Routledge. Place of Publication: London. Publication Year: 2001. Page Number:168

- Yarmouk 636, Conquest of Syria by David Nicolle

- title

- Augus Mcbride

- Kennedy, Hugh (2013). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-134-53113-4.

- The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. Contributors: Hugh Kennedy - author. Publisher: Routledge. Place of Publication: London. Publication Year: 2001. Page Number:59

- Tabari: Vol. 3, p. 8

- Ibn Kathir, Al-Bidayah wan-Nihayah, Dar Abi Hayyan, Cairo, 1st ed. 1416/1996, Vol. 6 P. 425.

- al-Waqdi Fatuh-al-sham page 61

- A. I. Akram (1970). The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed, His Life and Campaigns. National Publishing House, Rawalpindi. ISBN 0-7101-0104-X.

- Annals of the Early Caliphate By William Muir

- Tabari: Vol: 2, page no: 560.

- Patricia Crone, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, War article, p.456. Brill Publishers

- Micheline R. Ishay, The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalization Era, University of California Press, p.45

- Sohail H. Hashmi, David Miller, Boundaries and Justice: diverse ethical perspectives, Princeton University Press, p.197

- Douglas M. Johnston, Faith-Based Diplomacy: Trumping Realpolitik, Oxford University Press, p.48

- Aboul-Enein and Zuhur, p. 22

- Nadvi(2000), pg. 519

- Encyclopaedia of Islam (2005), p.204

- El Daly, Okasha (2004), Egyptology: The Missing Millennium : Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings, Routledge, p. 18, ISBN 1-84472-063-2