Ridda wars

The Ridda Wars (Arabic: حُرُوب ٱلرِّدَّة), or Wars of Apostasy, were a series of military campaigns launched by the Caliph Abu Bakr against rebel Arabian tribes during 632 and 633, just after the death of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad.[1] The rebels' position was that they had submitted to Muhammad as the prophet of Allah, but owed nothing to Abu Bakr.

| Ridda Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rashidun Caliphate | Rebel Arab tribes | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Abu Bakr Khalid ibn al-Walid Ikrima ibn Abi Jahl Amr ibn al-As Shurahbil ibn Hasana Khalid ibn Sa'id Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami Hudhayfah al-Bariqi Arfaja al-Bariqi Al-Muhajir ibn Abi Umayya Suwaid ibn Maqaran Shahr ibn Badhan † Fayruz al-Daylami |

Al-Aswad Al-Ansi † Qayth ibn Abd Yaghuth Tulayha Musaylima † Malik ibn Nuwayra † Sajah | ||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Saudi Arabia |

|

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Yemen |

|

| Timeline |

Some rebels followed either Tulayha, Musaylima or Sajjah, all of whom claimed prophethood. Most of the tribes were defeated and reintegrated into the Caliphate. The peoples surrounding Mecca did not revolt.

A detailed reconstruction of the events is complicated by the frequently contradictory and tendentious accounts found in primary sources.[2]

Prelude

In about the middle of May 632, Muhammad, now ailing, ordered a large expedition to be prepared against the Byzantine Empire in order to avenge the martyrs of the battle of Mu'tah. 3000 Muslims were to join it. Usama ibn Zaid, a young man and son of Zayd ibn Harithah who was killed in the battle at Mu'tah, was appointed as commander of this force so he could avenge the death of his father.[3][4][5] However, Muhammad died in June 632 and Abu Bakr was made the Caliph by a shura council in Saqifah.

On the first day of his caliphate, Abu Bakr ordered the army of Usama to prepare for march. Abu Bakr was under great pressure regarding this expedition due to rising rebellion and apostasy across Arabia, but he was determined.[6] Before his march, Usama sent Umar to Abu Bakr and is reported to have said:

Go to the Caliph, ask him to permit the army to remain at Medina. All the leaders of the community are with me. If we go, none will be left to prevent the infidels from tearing Medina to pieces.[7]

However, Abu Bakr refused. He was moved to this decision at least partially by his desire to carry out the unfulfilled military plan of Muhammad.

On June 26, 632, the army of Usama broke camp and moved out. After leaving Medina, Usama had marched to Tabuk. Most of the tribes in this region opposed him fiercely, but he defeated them. Usama raided far and wide in the region of Northern Arabia, starting with the Quza'a, and then made his way to Dawmatu l-Jandal (modern Al Jawf, Saudi Arabia).

As a direct result of his operations, several rebel tribes resubmitted to Medinian rule and claimed that they re-accepted Islam. The Quza'a remained rebellious and unrepentant, but 'Amr ibn al-'As later attacked them and forced them to surrender again.[1]

Usama next marched to Mu'tah, attacked the Christian Arabs of the tribes of Banu Kalb and the Ghassanids in a small battle. Then he returned to Medina, bringing with him a large number of captives and a considerable amount of wealth, part of which comprised the spoils of war and part taxation of the re-conquered tribes. The Islamic army remained out of Medina for 40 days.

Defence of Medina

The concentrations of rebels nearest Medina were located in two areas: Abraq, 72 miles to the north-east, and Dhu Qissa, 24 miles to the east.[8] These concentrations consisted of the tribes of Banu Ghatafan, the Hawazin, and the Tayy. Abu Bakr sent envoys to all the enemy tribes, calling upon them to remain loyal to Islam and continue to pay their Zakat.

A week or two after the departure of Usama's army, the rebel tribes surrounded Medina, knowing that there were few fighting forces in the city. Meanwhile, Tulayha, a self-proclaimed prophet, reinforced the rebels at Dhu Qissa. In the third week of July 632, the apostate army moved from Dhu Qissa to Dhu Hussa, from where they prepared to launch an attack on Medina.

Abu Bakr received intelligence of the rebel movements, and immediately prepared for the defense of Medina. As Usama's army was elsewhere, Abu Bakr scraped together a fighting force mainly from the clan of Muhammad, the Banu Hashim. The army had stalwarts like Ali ibn Abi Talib, Talha ibn Ubaidullah and Zubair ibn al-Awam, who would later (in the 640s) conquer Egypt. Each of them was appointed commander of one-third of the newly organised force. Before the apostates could do anything, Abu Bakr launched his army against their outposts and drove them back to Dhu Hussa.

The following day, Abu Bakr marched from Medina with the main army and moved towards Dhu Hussa.[1] As the riding camels were all with Usama's army, he could only muster inferior pack camels as mounts. These pack camels, being untrained for battle, bolted when Hibal, the apostate commander at Zhu Hussa, made a surprise attack from the hills; as a result, the Muslims retreated to Medina, and the apostates recaptured the outposts that they lost a few days earlier. At Medina, Abu Bakr reorganised the army for battle and attacked the apostates during the night, taking them by surprise. The apostates retreated from Dhu Hussa to Dhu Qissa. The following morning, Abu Bakr led his forces to Dhu Qissa, and defeated the rebel tribes, capturing Dhu Qissa on 1 August 632.

The defeated apostate tribes retreated to Abraq, where more clansmen of the Ghatfan, the Hawazin, and the Tayy were gathered. Abu Bakr left a residual force under the command of An-Numan ibn Muqarrin at Dhu Qissa and returned with his main army to Medina.

On 4 August 632, Usama's army returned to Medina. Abu Bakr ordered Usama to rest and resupply his men there for future operations. Meanwhile, in the second week of August 632, Abu Bakr moved his army to Zhu Qissa. Merging An-Numan ibn Muqarrin's remaining forces with his own, Abu Bakr then moved to Abraq, where the retreated rebels had gathered, and defeated them. The remaining rebels retreated to Buzakha, where Tulayha had moved with his army from Samira.

Abu Bakr's strategy

In the fourth week of August 632, Abu Bakr moved to Zhu Qissa with all available fighting forces. There he planned his strategy, in what would later be called the Campaign of Apostasy, to deal with the various enemies who occupied the rest of Arabia.[8] The battles which he had fought recently against the apostate concentrations at Zhu Qissa and Abraq were in the nature of defensive actions to protect Medina and discourage further offensives by the enemy. These actions enabled Abu Bakr to secure a base from which he could fight the major campaign that lay ahead, thus gaining time for the preparation and launching of his main forces.

Abu Bakr had to fight not one but several enemies: Tulayha at Buzakha, Malik bin Nuwaira at Butah, and Musaylima at Yamamah. He had to deal with widespread apostasy on the eastern and southern coasts of Arabia: in Bahrain, in Oman, in Mahra, in Hadhramaut and in Yemen. There was apostasy in the region south and east of Mecca and by the Quza'a in northern Arabia.

Abu Bakr formed the army into several corps, the strongest of which was commanded by Khalid ibn Walid and assigned to fight the most powerful of the rebel forces. Other corps were given areas of secondary importance in which to subdue the less dangerous apostate tribes, and were dispatched after Khalid, according to the outcome of his operations. Abu Bakr's plan was first to clear west-central Arabia (the area nearest to Medina), then tackle Malik bin Nuwaira, and finally concentrate against the most dangerous and powerful enemy: the self-proclaimed prophet Musaylima.

Military organization

The caliph distributed the available manpower among 11 main corps, each under its own commander, and bearing its own standard. The available manpower was distributed among these corps, and while some commanders were given immediate missions, others were given missions to be launched later. The commanders and their assigned objectives were:

- Khalid Ibn Walid: Move against Tulaiha bin Khuwailad Al-Asdee (طُلیحہ بن خویلد الاسدی) from the Asad Tribe (بنو اسد) at Buzaakhah (بزاخہ), then Malik bin Nuwaira, at Butah.

- Ikrimah ibn Abi-Jahl: Confront Musaylima at Yamamah but not to engage until more forces were built up.

- Amr ibn al-As: The apostate tribes of Quza'a and Wadi'a in the area of Tabuk and Daumat-ul-Jandal.

- Shurahbil ibn Hasana: Follow Ikrimah and await the Caliph's instructions.

- Khalid bin Saeed: Certain apostate tribes on the Syrian frontier.

- Turaifa bin Hajiz: The apostate tribes of Hawazin and Bani Sulaim in the area east of Medina and Mecca.

- Ala bin Al Hadhrami: The apostates in Bahrain.

- Hudhaifa bin Mihsan: The apostates in Oman.

- Arfaja bin Harthama.: The apostates in Mahra.

- Muhajir bin Abi Umayyah: The apostates in the Yemen, then the Kinda in Hadhramaut.

- Suwaid bin Muqaran: The apostates in the coastal area north of the Yemen.

As soon as the organisation of the corps was complete, Khalid marched off, to be followed a little later by Ikrimah and 'Amr ibn al-'As. The other corps were held back by the caliph and dispatched weeks and even months later, according to the progress of Khalid's operations against the hard core of enemy opposition.[1]

Before the various corps left Zhu Qissa, however, envoys were sent by Abu Bakr to all apostate tribes in a final attempt to induce them to submit.

Campaigns

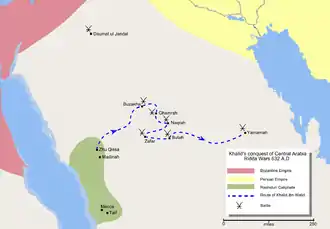

Central Arabia

Apostasy and rebellion in central Arabia was led by Musaylima, a self-proclaimed prophet, in the fertile region of Yamamah. He was mainly supported by the powerful tribe of Banu Hanifa. At Buzakha in north central Arabia, another self-proclaimed prophet, Tulayha, a tribal chief of Banu Asad, led the rebellion against Medina aided by the allied tribes of Banu Ghatafan, the Hawazin, and the Tayy. At Najd, Malik ibn Nuweira led the tribes of Banu Tamim against the authority of Medina.[9]

Buzakha

On receiving intelligence of the Muslim preparations, Tulayha too prepared for battle, and was further reinforced by the contingents of the allied tribes.

Before dispatching Khalid against Tulayha, Abu Bakr sought to reduce the latter's strength. Nothing could be done about the tribes of Bani Assad and Banu Ghatafan, which stood solidly behind Tulayha, but the Tayy were not so staunch in their support of Tulayha, and their chief, Adi ibn Hatim, was a devout Muslim.

Adi was appointed by Abu Bakr to negotiate with the tribal elders to withdraw their contingent from Tulayha's army. The negotiations were a success, and Adi brought with him 500 horsemen of his tribe to reinforce Khalid's army.

Khalid next marched against another apostate tribe, Jadila. Here again Adi ibn Hatim offered his services to persuade the tribe to submit without bloodshed. Bani Jadila submitted, and their 1000 warriors joined Khalid's army.

Khalid, now much stronger than when he had left Zhu Qissa, marched for Buzakha. There, in mid-September 632 CE, he defeated Tulayha in the Battle of Buzakha. The remnants of Tulayha's army retreated to Ghamra, 20 miles from Buzakha, and were defeated in the Battle of Ghamra in the third week of September.

Several tribes submitted to the Caliph after Khalid's decisive victories. Moving south from Buzakha, Khalid reached Naqra in October, with an army now 6000 strong, and defeated the rebel tribe of Banu Saleem in the Battle of Naqra. In the third week of October, Khalid defeated a tribal chieftess, Salma, in the battle of Zafar. Afterwards he moved to Najd against the rebel tribe of Banu Tamim and their Sheikh Malik ibn Nuwayrah.

Najd

At Najd, on learning of Khalid's decisive victories against apostates in Buzakha, many clans of Banu Tamim hastened to visit Khalid, but the Bani Yarbu', a branch of Bani Tamim, under their chief, Malik ibn Nuwayrah, hung back. Malik was a chief of some distinction: a warrior, noted for his generosity, and a famous poet. Bravery, generosity, and poetry were the three qualities most admired among the Arabs.

At the time of Muhammad, he had been appointed as a tax collector for the tribe of Banu Tamim. As soon as Malik heard of the death of Muhammad, he gave back all the tax to his tribespeople, saying, "Now you are the owner of your wealth."[10] Most scholars agreed that he was adhering to the normal beliefs of the Arabs of his time in which they could cease to pledge their allegiance to a tribe upon the death of its Sheikh.

His riders were stopped by Khalid's army at the town of Buttah. Khalid asked them about the pact they signed with the self-proclaimed prophetess Sajjah; they responded it was merely for revenge against their enemies.[11]

When Khalid reached Najd he found no opposing army. He sent his cavalry to nearby villages and ordered them to call the Azaan (call to prayer) to each party they met. Zirrar bin Azwar, a squadron leader, arrested the family of Malik, claiming they did not answer the call to prayer. Malik avoided direct contact with Khalid's army and ordered his followers to scatter, and he and his family apparently moved away across the desert.[12] He refused to give zakat, differentiating between prayer and zakat.

Nevertheless, Malik was accused of rebellion against the state of Medina. He was also to be charged for his entering into the alliance with Sajjah against the Caliphate.[13] Malik was arrested along with those of his clan.[14]

Malik was asked by Khalid about his crimes, and responded, "your master said this, your master said that", referring to Abu Bakr. Khalid declared Malik a rebel apostate and ordered his execution.[15]

Yamamah

Ikrimah ibn Abi-Jahl, one of the corps commanders, was instructed to make contact with Musaylima at Yamamah, but not to engage until Khalid joined him. Abu Bakr's intention in giving Ikrimah this mission was to tie Musaylima down at Yamamah, thereby freeing Khalid to deal with the apostate tribes of north-central Arabia without interference.

Meanwhile, Abu Bakr sent Shurhabil's corps to reinforce Ikrimah at Yamamah. Ikrimah, however, in early September 632, attacked Musaylima's forces before the reinforcements arrived, and was defeated. He reported his actions to Abu Bakr, who, both pained and angered by the rashness of Ikrimah and his disobedience, ordered him to proceed with his force to Oman to assist Hudaifa; once Hudaifa had completed his task, he was to march to Mahra to help Arfaja, and thereafter go to Yemen to help Muhajir.[16]

Meanwhile, Abu Bakr sent orders to Khalid to march against Musaylima. Shurhabil's corps, stationed at Yamamah, was to reinforce Khalid's corps. In addition to this Abu Bakr assembled a fresh army of Ansar and Muhajireen in Medina that joined Khalid's corps at Butah before the combined force set out for Yamamah.

Though Abu Bakr had instructed Shurhabil not to engage Musaylima's forces until Khalid's arrival, Shurhabil engaged Musaylima's forces anyway and was defeated, too. Khalid linked up with the remnants of Shurhabil's corps early in December 632.

The combined force of Muslims, now 13,000 strong, finally defeated Musaylima's army in the Battle of Yamama, which was fought in the third week of December. The fortified city of Yamamah surrendered peacefully later that week.[16]

Khalid established his headquarters at Yamamah, from which he despatched columns throughout the plain of Aqraba to subdue the region around Yamamah. Thereafter, all of central Arabia submitted to Medina.

What remained of the apostasy in the less vital areas of Arabia was rooted out by the Muslims in a series of well-planned campaigns within five months.

Oman

In mid-September 632, Abu Bakr dispatched Hudaifa bin Mihsan's corps to tackle the apostasy in Oman, where the dominant tribe of Azd had revolted under their chief Laqeet bin Malik, known more commonly as "Dhu'l-Taj" ("the Crowned One"). According to some reports, he also claimed prophethood.

Hudaifa entered Oman, but not having sufficient strength to fight Dhu'l-Taj, he requested reinforcements from the Caliph, who sent Ikrimah from Yamamah to aid him in late September. The combined forces then defeated Dhu'l-Taj at a battle at Dibba, one of Dhu'l-Taj's strongholds, in November. Dhu'l-Taj himself was killed in the battle.[17]

Hudaifa was appointed governor of Oman, and set about the re-establishment of law and order. Ikrimah, having no local administrative responsibility, used his corps to subdue the area around Daba, and, in a number of small actions, succeeded in breaking the resistance of those Azd who had continued to defy the authority of Medina.[1]

Northern Arabia

Some time in October 632, Amr's corps was dispatched to the Syrian border to subdue the apostate tribes—most importantly, the Quza'a and the Wadi'a (a part of the Bani Kalb)--in the region around Tabuk and Daumat-ul-Jandal (Al-Jawf). Amr was not able to beat the tribes into submission until Shurhabil joined him in January after the Battle of Yamamah.

Yemen

The Yemen had been the first province to rebel against the authority of Islam when the tribe of Ans rose in arms under the leadership of its chief and self-proclaimed prophet Al-Aswad Al-Ansi, the Black One. Yemen was controlled then by Al-Abna', a group descended from the Sasanian Persian garrison in Sanaa. When Badhan died, his son Shahr partially became governor of Yemen but was killed by Al-Aswad. Al-Aswad was later killed by Fayruz al-Daylami, also an abna' member, who was sent by Muhammad, and thereafter Fairoz acted as governor of Yemen at San'a.[8][18]

When word arrived that Mohammad had died, the people of the Yemen again revolted, this time under the leadership of a man named Ghayth ibn Abd Yaghuth. The avowed aim of the apostates was to drive the Muslims out of the Yemen by assassinating Fairoz and other important Muslim leaders. Fairoz somehow escaped and took shelter in the mountains in June or July 632. For the next six months Fairoz remained in his stronghold, during which time he was joined by thousands of Yemeni Muslims.[15]

When he felt strong enough, Fairoz marched to San'a and defeated Qais, who retreated with his remaining men northeast to Abyan, where they all surrendered and were subsequently pardoned by the caliph.[8]

Mahra

From Oman, following the orders of Abu Bakr, Ikrimah marched to Mahra to join Arfaja bin Harthama. As Arfaja had not yet arrived, Ikrimah, instead of waiting for him, tackled the local rebels on his own.

At Jairut, Ikrimah met two rebel armies preparing for battle. Here he persuaded the weaker to embrace Islam and then joined up with them to defeat their opponents. Having re-established Islam in Mahra, Ikrimah moved his corps to Abyan, where he rested his men and awaited further developments.

Bahrain

After the Battle of Yamamah, Abu Bakr sent Ala bin Al Hadhrami's corps against the rebels of Bahrain. Ala arrived in Bahrain to find the apostate forces gathered at Hajr and entrenched in a strong position. Ala mounted a surprise attack one night and captured the city. The rebels retreated to the coastal regions, where they made one more stand but were decisively defeated. Most of them surrendered and reverted to Islam. This operation was completed at about the end of January 633.

Hadhramaut

The last of the great revolts of the apostasy was that of the powerful tribe of Kindah, which inhabited the region of Najran, Hadhramaut, and eastern Yemen. They did not break into revolt until January 633. [15]

Ziyad bin Lubaid, Muslim governor of Hadhramaut, operated against them and raided Riyaz, after which the whole of the Kindah broke into revolt under al-Ash'ath ibn Qays and prepared for war. However, the strength of the two forces, i.e. apostate and Muslim, was so well balanced that neither side felt able to start serious hostilities. Ziyad waited for reinforcements before attacking the rebels.

Reinforcements were on the way. al-Muhajir ibn Abi Umayya, the last of the corps commanders to be despatched by Abu Bakr, defeated some rebel tribes in Najran, south-eastern Arabia, and was directed by Abu Bakr to march to Hadhramaut and join Ziyad against the Kindah. The Caliph also instructed Ikrimah, who was at Abyan, to join Ziyad and Muhajir's forces.

In late January 633 the forces of Muhajir and Ziyad combined at Zafar, capital of Hadhramaut, under the overall command of the former, and defeated al-Ash'ath, who retreated to the fortified town of Nujair.

Just after this battle the corps of Ikrimah also arrived. The three Muslim corps, under the overall command of Muhajir, advanced on Nujair and laid siege to the fortified city.

Nujair was captured some time in mid-February 633. With the defeat of the Kindah at Nujair the last of the great apostate movements collapsed. Arabia was safe for Islam.

The Campaign of the Apostasy was fought and completed during the 11th year of the Hijra. The year 12 Hijri dawned on March 18, 633, with Arabia united under the central authority of the Caliph at Medina. This campaign was Abu Bakr's greatest political and military triumph, and was a complete success.

Aftermath

With the collapse of the rebellions, Abu Bakr now decided to expand the empire. It is unclear whether his intention was to mount a full-scale expansion, or preemptive attacks to secure a buffer zone between the Islamic state and the powerful Sassanid and Byzantine empires. This set the stage for the Islamic conquest of Persia.[15] Khalid was sent to the Persian Empire with an army consisting of 18,000 volunteers, and conquered the richest province of the Persian empire: Iraq. Thereafter, Abu Bakr sent his armies to invade Roman Syria, an important province of the Byzantine Empire.[19]

Consequences

The events were later regarded as primarily a religious movement by Arabic historians. However, the early sources indicate that in reality it was also an attempt to restore political control over the Arabian tribes.[8][20] After all, the rebelling Arabs only refused to pay Zakat (charity), but they did not refuse to perform the salah.[8] This, however, is disputed and explained by Sunni scholars such that the dictation of Zakat was one of the Five Pillars of Islam and its denial or withholding is an act of denial of a cornerstone of the faith, and is therefore an act of apostasy. Bernard Lewis states that the fact that Islamic historians have regarded this as a primarily religious movement was due to a later interpretation of events in terms of a theological world-view.[21] The opponents of the Muslim armies were not only apostates, but also tribes which were largely or even completely independent from the Muslim community.[8] However, these revolts also had a religious aspect: Medina had become the centre of a new Arabian social and political system of which religion was an integral part; consequently it was inevitable that any reaction against this system should have a religious aspect.[22]

See also

References

- Laura V. Vaglieri in The Cambridge History of Islam, p.58

- M. Lecker (2012). "Al-Ridda". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8870.

- Ibn Sad: p. 707

- Ella Landau-Tasseron (January 1998). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 39: Biographies of the Prophet's Companions and Their Successors: al-Tabari's Supplement to His History. SUNY Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7914-2819-1.

- Idris El Hareir; Ravane Mbaye (2011). The Spread of Islam Throughout the World. UNESCO. p. 187. ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2.

- Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 461.

- Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 462.

- Frank Griffel (2000). Apostasie und Toleranz im Islam: die Entwicklung zu al-Ġazālīs Urteil gegen die Philosophie und die Reaktionen der Philosophen (in German). BRILL. p. 61. ISBN 978-90-04-11566-8.

- Ibrahim Abed; Peter Hellyer (2001). United Arab Emirates: A New Perspective. Trident Press. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-1-900724-47-0.

- al-Balazuri: book no: 1, page no:107.

- Tabari: Vol 9 p. 501-2.

- Al-Tabari 915, pp. 501–502

- Al-Tabari 915, p. 496

- Al-Tabari 915, p. 502

- Tabari: Vol. 2, p. 5

- John Bagot Glubb (1963). The Great Arab Conquest. Hodder and Stoughton. p. 112.

- Muhammad Rajih Jad'an, Abu Bakr As-Siddiq. Retrieved August 26, 2006.

- "ABNĀʾ – Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- A.I. Akram (1 January 2009). "Chapter 18". Sword of Allah: Khalid Bin Al-Waleed His Life & Campaigns. Adam Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 978-81-7435-521-8.

- Laura V. Vaglieri in The Cambridge History of Islam, p.58

- Bernard Lewis (14 March 2002). Arabs in History. OUP Oxford. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-164716-1.

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol.1, p.110

Further reading

- Fred McGraw Donner: The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton University Press, 1986.ISBN 0691053278

- Elias S. Shoufani: Al-Riddah and the Muslim conquest of Arabia. Toronto, 1973. ISBN 0-8020-1915-3

- Meir J. Kister: The struggle against Musaylima and the conquest of Yamama. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, 27 (2002)

- Ella Landau-Tasseron: The Participation of Tayyi in the Ridda. In: Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, 5 (1984)