Religion in South Korea

Religion in South Korea is diverse. The majority of South Koreans (56.1%, as of the 2015 national census) are irreligious. Christianity and Buddhism are the dominant confessions among those who affiliate with a formal religion. Protestantism represents (19.7%) of the total population, Korean Buddhism (15.5%), and Catholicism (7.9%). A small percentage of South Koreans (0.8% in total) are members of other religions, including Won Buddhism, Confucianism, Cheondoism, Daesun Jinrihoe, Islam, Daejongism, Jeungsanism and Orthodox Christianity.[1]

.jpg.webp)

Buddhism was influential in ancient times and Christianity had influenced large segments of the population in the 18th and 19th century, yet they grew rapidly in membership only by the mid-20th century, as part of the profound transformations that South Korean society went through in the past century.[3] But they have shown some decline from the year 2000 onwards. Native shamanic religions (i.e. Sindo) remain popular and could represent a large part of the unaffiliated. Indeed, according to a 2012 survey, only 15% of the population declared themselves to be not religious in the sense of "atheism".[4] According to the 2015 census, the proportion of the unaffiliated is higher among the youth, about 69% among the 20-years old.[5]

Korea entered the 20th century with an already ingrained Christian presence and a vast majority of the population practicing native religion, Sindo. The latter never gained the high status of a national religious culture comparable to Chinese folk religion and Japan's Shinto; this weakness of Korean Sindo was among the reasons that left a free hand to an early and thorough rooting of Christianity.[6] The population also took part in Confucianising rites and held private ancestor worship.[3] Organised religions and philosophies belonged to the ruling elites and the long patronage exerted by the Chinese empire led these elites to embrace a particularly strict Confucianism (i.e. Korean Confucianism). Korean Buddhism, despite an erstwhile rich tradition, at the dawn of the 20th century was virtually extinct as a religious institution, after 500 years of suppression under the Joseon kingdom.[3][7] Christianity had antecedents in the Korean peninsula as early as the 18th century, when the philosophical school of Seohak supported the religion. With the fall of the Joseon in the last decades of the 19th century, Koreans largely embraced Christianity, since the monarchy itself and the intellectuals looked to Western models to modernise the country and endorsed the work of Catholic and Protestant missionaries.[8] During Japanese colonisation in the first half of the 20th century, the identification of Christianity with Korean nationalism was further strengthened,[9] as the Japanese tried to combine native Sindo with their State Shinto.

With the division of Korea into two states after 1945, the communist north and the capitalist south, the majority of the Korean Christian population that had been until then in the northern half of the peninsula,[10] fled to South Korea.[11] It has been estimated that Christians who migrated to the south were more than one million.[12] Throughout the second half of the 20th century, the South Korean state enacted measures to further marginalise indigenous Sindo, at the same time strengthening Christianity and a revival of Buddhism.[13] According to scholars, South Korean censuses do not count believers in indigenous Sindo and underestimate the number of adherents of Sindo sects.[14] Otherwise, statistics compiled by the ARDA[15] estimate that as of 2010, 14.7% of South Koreans practice ethnic religion, 14.2% adhere to new movements, and 10.9% practice Confucianism.[16]

According to some observers, the sharp decline of some religions (Catholicism and Buddhism) recorded between the censuses of 2005 and 2015 is due to the change in survey methodology between the two censuses. While the 2005 census was an analysis of the entire population ("whole survey") through traditional data sheets compiled by every family, the 2015 census was largely conducted through the internet and was limited to a sample of about 20% of the South Korean population. It has been argued that the 2015 census penalised the rural population, which is more Buddhist and Catholic and less familiar with the internet, while advantaging the Protestant population, which is more urban and has easier access to the internet. Both the Buddhist and the Catholic communities criticised the 2015 census' results.[5]

Demographics

Religious affiliation by year (1950–2015)

| Year | Buddhism | Catholicism | Protestantism | Other religions | No affiliation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | People | Percent | People | Percent | People | Percent | People | Percent | People | |

| 1950 [17] | — | — | 1% | — | 3% | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1960 [17] | 3% | — | 2% | — | 5% | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1970 [17] | 15% | — | 3% | — | 7% | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1985 [18] | 19.2% | 8,059,624 | 4.6% | 1,865,397 | 16% | 6,489,282 | 2.1% | 788,993 | 57.4% | 23,216,356 |

| 1995 [19] | 23.2% | 10,321,012 | 6.6% | 2,950,730 | 19.7% | 8,760,336 | 1.2% | 565,746 | 49.3% | 21,953,315 |

| 2005 [20] | 22.8% | 10,726,463 | 10.9% | 5,146,147 | 18.3% | 8,616,438 | 1% | 481,718 | 46.9% | 21,865,160 |

| 2015 [1] | 15.5% | 7,619,332 | 7.9% | 3,890,311 | 19.7% | 9,675,761 | 0.8% | 368,270 | 56.1% | 27,498,715 |

| "—" denotes that no data is available. Other religions include Won Buddhism, Confucianism, Cheondoism, Daesun Jinrihoe, Daejongism, and Jeungsanism. | ||||||||||

Religious affiliation by age (2015)

| Age [1] | Buddhism | Catholicism | Protestantism | Other religions | No affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 10% | 7% | 18% | 1% | 65% |

| 30-39 | 12% | 8% | 19% | 1% | 62% |

| 40-49 | 16% | 7% | 20% | 1% | 57% |

| 50-59 | 22% | 9% | 19% | 1% | 49% |

| 60-69 | 26% | 10% | 21% | 1% | 42% |

| 70-79 | 27% | 10% | 21% | 1% | 41% |

| 80-85 | 24% | 10% | 22% | 2% | 42% |

| above 85 | 21% | 11% | 23% | 2% | 43% |

| Other religions include Won Buddhism, Confucianism, Cheondoism, Daesun Jinrihoe, Daejongism, and Jeungsanism. | |||||

Religious affiliation by gender (2015)

| Gender [1] | Buddhism | Catholicism | Protestantism | Other religions | No affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 14% | 7% | 18% | 1% | 61% |

| Female | 17% | 9% | 22% | 1% | 52% |

| Other religions include Won Buddhism, Confucianism, Cheondoism, Daesun Jinrihoe, Daejongism, and Jeungsanism. | |||||

History

Before 1945

Prior to the introduction of Buddhism, all Koreans believed in their indigenous religion socially guided by mu (shamans). Buddhism was introduced from the Chinese Former Qin state in 372 to the northern Korean state of Goguryeo and developed into distinctive Korean forms. At that time, the peninsula was divided into three kingdoms: the aforementioned Goguryeo in the north, Baekje in the southwest, and Silla in the southeast. Buddhism reached Silla only in the 5th century, but it was made the state religion only in that kingdom in the year 552.[21] Buddhism became much more popular in Silla and even in Baekje (both areas now part of modern South Korea), while in Goguryeo the Korean indigenous religion remained dominant. In the following unified state of Goryeo (918–1392) Buddhism flourished, and even became a political force.[22]

The Joseon kingdom (1392–1910), adopted an especially strict version of Neo-Confucianism (i.e. Korean Confucianism) and suppressed and marginalised Korean Buddhism[23][24] and Korean shamanism.[7] Buddhist monasteries were destroyed, and their number dropped from several hundreds to a mere thirty-six; Buddhism was eradicated from the life of towns as monks and nuns were prohibited from entering them and were marginalised to the mountains.[24] These restrictions lasted until the 19th century.[25]

In the late 19th century, the Joseon state was politically and culturally collapsing.[26] The intelligentsia was looking for solutions to invigorate and transform the nation.[26] It was in this critical period that they came into contact with Western Christian missionaries who offered a solution to the plight of Koreans.[26] Christian communities already existed in Joseon since the 17th century, however it was only by the 1880s that the government allowed a large number of Western missionaries to enter the country.[27] Christian missionaries set up schools, hospitals and publishing agencies.[28] The royal family supported Christianity.[29]

During the absorption of Korea into the Japanese Empire (1910–1945) the already formed link of Christianity with Korean nationalism was strengthened,[9] as the Japanese tried to impose State Shinto, co-opting within it native Korean Sindo, and Christians refused to take part in Shinto rituals.[9] At the same time, numerous religious movements that since the 19th century had been trying to reform the Korean indigenous religion, notably Cheondoism, flourished.[30]

1945–present

With the division of Korea into two states in 1945, the communist north and the anti-communist south, the majority of the Korean Christian population that had been until then in the northern half of the peninsula,[10] fled to South Korea.[11] Christians who resettled in the south were more than one million. Cheondoists, who were concentrated in the north like Christians, remained there after the partition,[30] and South Korea now has no more than few thousands Cheondoists.

The so-called "movement to defeat the worship of gods" promoted by governments of South Korea in the 1970s and 1980s, prohibited indigenous cults and wiped out nearly all traditional shrines (sadang 사당) of the Confucian kinship religion.[31] This was particularly tough under the rule of Park Chung-hee, who was a Buddhist.[32]

This measure, combined with the rapid social changes of the same period,[3] favoured a rapid revival of Korean Buddhism and growth of Christian churches in a trend to register as members of organised religions.[33] The number of Buddhist temples rose from 2,306 in 1962 to 11,561 in 1997, Protestant churches rose from 6,785 in 1962 to 58,046 in 1997, the Catholic Church had 313 churches in 1965 and 1,366 in 2005, Won Buddhism had 131 temples in 1969 and 418 in 1997.[34] Similarly, Daesun Jinrihoe's temples have grown from 700 in 1983 to 1,600 in 1994.[35] Statistics from censuses show that the proportion of the South Korean population self-identifying as Buddhist has grown from 2.6% in 1962 to 22.8% in 2005,[3] while the proportion of Christians has grown from 5% in 1962 to 29.2% in 2005.[3] However, both religions have shown a decline between the years 2005 and 2015, with Buddhism sharply declining in influence to 15.5% of the population, and a less significant decline of Christianity to 27.6%.[36]

Protestant attacks on traditional religions

Since the 1980s and the 1990s there have been acts of hostility committed by Protestants against Buddhists and followers of traditional religions in South Korea. This include the arson of temples, the beheading of statues of Buddha and bodhisattvas, and red Christian crosses painted on either statues or other Buddhist and other religions' properties.[37] Some of these acts have even been promoted by churches' pastors.[37]

Dominant religions

Buddhism

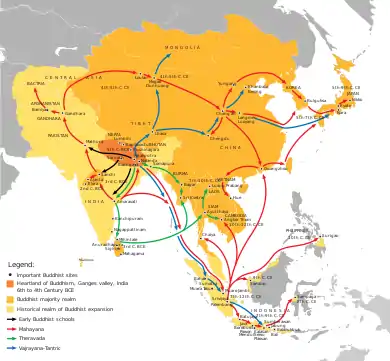

Arrival and spread since 4th century

Buddhism (불교/佛敎 Bulgyo) entered Korea from China during the period of the three kingdoms (372, or the 4th century).[21] Buddhism was the dominant religious and cultural influence in the North–South States Period (698–926) and subsequent Goryeo (918-1392) states. Confucianism was also brought to Korea from China in early centuries, and was formulated as Korean Confucianism in Goryeo. However, it was only in the subsequent Joseon kingdom (1392–1910) that Korean Confucianism was established as the state ideology and religion, and Korean Buddhism underwent 500 years of suppression.[23][24] Buddhism in the contemporary state of South Korea is stronger in the east of the country, namely the Yeongnam and Gangwon regions, as well as in Jeju.

Korean Zen or Seon Buddhism

There are a number of different schools in Korean Buddhism (대한불교/大韓佛敎 Daehanbulgyo), including the Seon (Korean Zen). Seon is represented by Jogye Order and Taego Order.[38] The overwhelming majority of Buddhist temples in contemporary South Korea belong to the dominant Jogye Order, traditionally related to the Seon school. The order's headquarters are at Jogyesa in central Seoul, and it operates most of the country's old and famous temples, such as Bulguksa and Beomeosa. Jogye requires their monastics to be celibate. Taego lineage is a form of Seon (Zen) and it differs from Seon by allowing priests to marry.

Jingak and Cheontae Buddhism

Jingak Order, is a modern esoteric form of Vajrayana Buddhism, which also permits its priests to marry. Cheontae is a modern revival of the Tiantai lineage in Korea, focusing on the Lotus Sutra. Cheontae orders requires their monastics to be celibate.[38]

Won Buddhism

Won Buddhism (원불교/圓佛敎 Wonbulgyo) is a modern reformed Buddhism that seeks to make enlightenment possible for everyone and applicable to regular life. The scriptures and practices are simplified so that anyone, regardless of their wealth, occupation, or other external living conditions, can understand them.[39]

Growth: Number of temples by denomination

| School | Temples |

| Jogye Order (조계종/曹溪宗) | 735 (81%) |

| Cheontae Order (천태종/天台宗) | 144 (16%) |

| Taego Order (태고종/太古宗) | 102 (11%) |

| Beobhwa Order (법화종/法華宗) | 22 (2%) |

| Seonhag-won (선학원/禪學院) | 16 (2%) |

| Wonhyo Order (원효종/元曉宗) | 5 (1%) |

| Other | 27 (3%) |

Buddhism's syncretic influence on Korea culture

According to a 2005 government survey, a quarter of South Koreans are practicing Buddhist.[42] However, the actual number of Buddhists in South Korea is ambiguous as there is no exact or exclusive criterion by which Buddhists can be identified, unlike the Christian population. With Buddhism's incorporation into traditional Korean culture, it is now considered a philosophy and cultural background rather than a formal religion. As a result, many people outside of the practicing population are deeply influenced by these traditions. Thus, when counting secular believers or those influenced by the faith while not following other religions, the number of Buddhists in South Korea is considered to be much larger.[43] Similarly, in officially atheist North Korea, while Buddhists officially account for 4.5% of the population, a much larger number (over 70%) of the population are influenced by Buddhist philosophies and customs.[44][45]

Christianity

Arrival in late 18th century

Foreign Roman Catholic missionaries did not arrive in Korea until 1794, a decade after the return of Yi Sung-hun, a diplomat who was the first baptised Korean in Beijing.[46] He established a grass roots lay Catholic movement in Korea. However, the writings of the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, who was resident at the imperial court in Beijing, had been already brought to Korea from China in the 17th century. Scholars of the Silhak ("Practical Learning") were attracted to Catholic doctrines, and this was a key factor for the spread of the Catholic faith in the 1790s.[47]

Denominations

The Christianity (그리스도교/----敎 Geurisdogyo or 기독교/基督敎 Gidoggyo, both meaning religion of Christ) in South Korea is dominated by four denominations: Protestant Presbyterianism (장로교 pronounced Jangnogyo), Catholic (천주교/天主敎 pronounced Cheonjugyo), Methodism (감리교 pronounced Gamnigyo) and Baptists (침례교 pronounced Chimnyegyo). The Yoido Full Gospel Church is the largest Pentecostal church in the country. Some non-denominational churches also exist.[48] According to 2015 census, Protestants and Catholics numbered 9.6 million and 3.8 million respective. There are also small Eastern Orthodox communities.

Roman Catholicism

The penetration of Western ideas and Christianity in Korea became known as Seohak ("Western Learning"). A study of 1801 found that more than half of the families that had converted to Catholicism were linked to the Seohak school.[49] Largely because converts refused to perform Confucian ancestral rituals, the Joseon government prohibited Christian proselytising. Some Catholics were executed during the early 19th century, but the restrictive law was not strictly enforced. Finally, Catholicism in Korea was growing during the 1970s and 1980s.

Protestantism

Protestant missionaries entered Korea during the 1880s and, along with Catholic priests, converted a remarkable number of Koreans, this time with the support of the royal government which winked at Westernising forces in a period of deep internal crisis (due to the waning of centuries-long patronage from a then-weakened China).[29] The lack of a national religious system compared to those of China and that of Japan (Korean Sindo never developed to a high status of institutional and civic religion) gave a free hand to Christian churches.[6] Methodist and Presbyterian missionaries were especially successful. They established schools, universities, hospitals, and orphanages and played a significant role in the modernisation of the country.[28]

Eastern Christianity

Orthodox Christian missionaries entered Korea from Russia in 1900. In 1903, the first Orthodox church in Korea was established. However, the Russo-Japanese war in 1904 and the Russian Revolution in 1918 interrupted the activities of the mission. A large number of Christians lived in the northern part of the peninsula (it was part of the so-called "Manchurian revival")[29] where Confucian influence was not as strong as in the south.[10] Before 1948 Pyongyang was an important Christian centre: one-sixth of its population of about 300,000 people were converts. Following the establishment of the communist regime in the north, an estimated more than one million Korean Christians resettled to South Korea to escape persecution by North Korea's anti-Christian policies.[11]

The non-Chalcedonian Coptic Church of Alexandria was first established in Seoul in 2013 for Egyptian Copts and Ethiopians residing in South Korea.

Other sects

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in South Korea was established following the baptism of Kim Ho Jik in 1951,[50] which had 81,628 members in 2012 with one temple in Seoul.[51] four Mormon missions (Seoul, Daejeon, Busan, and Seoul South),[52] 128 congregations, and twenty-four family history centres.[53]

Sun Myung Moon's Unification Church (통일교 Tongilgyo)[54] is a new religious movement founded in South Korea in 1954 by Sun Myung Moon, which has financed many organizations and businesses in news media, education, politics and social activism.[55] In 2003, Korean Unification Church members started a political party named "The Party for God, Peace, Unification, and Home".[56]

World Mission Society Church of God and the Victory Altar are other Korean new religious movements that originated within Christianity.

Anabaptist peace churches have not gained a strong foothold on the peninsula. Quaker thought briefly attracted a national following in the late 20th century, due to the efforts of Ham Seok-heon. However, after Ham's death, interest in Quakerism declined. The state of Unitarianism is similar.

Causes of growth of Christianity

Factors contributing to the growth of Catholicism and Protestantism included the decayed state of Korean Buddhism, the support of the intellectual elite, and the encouragement of self-support and self-government among members of the Korean church, and finally the identification of Christianity with Korean nationalism.[29] Christianity grew significantly in the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1990s it continued to grow, but at a slower rate, and since the 2000s it has shown some decline. Christianity is especially dominant in the west of the country including Seoul, Incheon, and the regions of Gyeonggi and Honam.[48]

Ban and opposition to syncretic aspects

Fundamentalist Christians continue to oppose the syncretic aspects of the culture including confucian traditions and ancestral rites practiced even by the secular people and followers of other faiths.[57][58][59] Mantienne, Frédéric 1999 Monseigneur Pigneau de Béhaine, Editions Eglises d'Asie, 128 Rue du Bac, Paris, ISSN 1275-6865 ISBN 2-914402-20-1, pp.177-82.</ref>[60][43] Consequently, many Korean Christians, specially protestants, have abandoned these native Korean traditions.[61][62] Protestants in Korea have a history of attacking Buddhism and other traditional religions of Korea with arson and vandalism of temple and statues, some of these hostile acts have been promoted by the church.[37]

After the ban on syncretic traditions was lifted by the Pope,[57] Korean Catholics still observe jesa (ancestral rites); the Korean tradition is very different from the institutional religious ancestral worship that is found in China and Japan and can be easily integrated as ancillary to Catholicism. Orthodox and Protestants, by contrast, have completely abandoned the practice.[48]

Indigenous religions

.jpg.webp)

Korean shamanism

Korean shamanism, also known as "Muism" (무교 Mugyo, "mu [shaman] religion")[63] and "Sindo" (신도) or "Sinism" (신교 Singyo "Way of the Gods").[64][65] is the native religion of the Koreans.[66][note 1] Although used synonymously, the two terms aren't identical:[66] Jung Young Lee describes Muism as a form of Sindo - the shamanic tradition within the religion.[67] Particularly akin to Japan's Shinto, contrarywise to it and to China's religious systems, Korean Sindo never developed into a national religious culture.[6]

In contemporary Korean language the shaman-priest or mu (hanja: 巫) is known as a mudang (Hangul: 무당 hanja: 巫堂) if female or baksu if male, although other names and locutions are used.[66][note 2] Korean mu "shaman" is synonymous with Chinese wu, which defines priests both male and female.[67] The role of the mudang is to act as intermediary between the spirits or gods, and the human plain, through gut (rituals), seeking to resolve problems in the patterns of development of human life.[69]

Central is interaction with Haneullim or Hwanin, meaning "source of all being",[70] and of all gods of nature,[67] the utmost god or the supreme mind.[71] The mu are mythically described as descendants of the "Heavenly King", son of the "Holy Mother [of the Heavenly King]", with investiture often passed down through female princely lineage.[72] However, other myths link the heritage of the traditional faith to Dangun, male son of the Heavenly King and initiator of the Korean nation.[73]

Besides Japanese Shinto, Korean religion has also similarities with Chinese Wuism,[74] and is akin to the Siberian, Mongolian, and Manchurian religious traditions.[74] Some studies trace the Korean ancestral god Dangun to the Ural-Altaic Tengri "Heaven", the shaman and the prince.[75][76] In the dialects of some provinces of Korea the shaman is called dangul dangul-ari.[70] The mudang is similar to the Japanese miko and the Ryukyuan yuta. Muism has exerted an influence on some Korean new religions, such as Cheondoism and Jeungsanism. According to various sociological studies, Korea's type of Christianity owes much of its success to native shamanism, which provided a congenial mindset and models for the religion to take root.[77]

In the 1890s, the last decades of the Joseon kingdom, Protestant missionaries gained significant influence, and led a demonisation of native religion through the press, and even carried out campaigns of physical suppression of local cults.[78] The Protestant discourse would have had an influence on all further attempts to uproot native religion.[78] The "movement to destroy Sindo" carried out in South Korea in the 1970s and 1980s, destroyed much of the physical heritage of Korean religion (temples and shrines),[31] especially during the regime of President Park Chung-hee.[32][79][80] There has been of a revival of shamanism in South Korea in most recent times.[81][82]

Cheondoism

Cheondoism (천도교 Cheondogyo) is a fundamentally Confucian religious tradition derived from indigenous Sinism. It is the religious dimension of the Donghak ("Eastern Learning") movement that was founded by Choe Je-u (1824-1864), a member of an impoverished yangban (aristocratic) family,[83] in 1860 as a counter-force to the rise of "foreign religions",[84] which in his view included Buddhism and Christianity (part of Seohak, the wave of Western influence that penetrated Korean life at the end of the 19th century).[84] Choe Je-u founded Cheondoism after having been allegedly healed from illness by an experience of Sangje or Haneullim, the god of the universal Heaven in traditional shamanism.[84]

The Donghak movement became so influential among common people that in 1864 the Joseon government sentenced Choe Je-u to death.[84] The movement grew and in 1894 the members gave rise to the Donghak Peasant Revolution against the royal government. With the division of Korea in 1945, most of the Cheondoist community remained in the north, where the majority of them dwelled.[30] Only few thousands of them remain in South Korea today.

The social and historical significance of the Donghak movement and Cheondoism has been largely ignored in South Korea,[85] contrarywise to North Korea where Cheondoism is viewed positively as a folk (minjung) movement.[85]

Other sects

Apart from Cheondoism, other sects based on indigenous religion were founded between the end of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century. They include Daejongism (대종교 Daejonggyo),[86] which has as its central creed the worship of Dangun, legendary founder of Gojoseon, thought of as the first proto-Korean kingdom; and a splinter sect of Cheondoism: Suwunism.

Jeungsanism (증산교 Jeungsangyo) defines a family of religions founded in the early 20th century[87] that emphasise magical practices and millenarian teachings of Kang Jeungsan (Gang Il-Sun). There are more than a hundred "Jeungsan religions," including the now defunct Bocheonism: the largest in Korea is currently Daesun Jinrihoe (대순진리회), an offshoot of the still existing Taegeukdo (태극도), while Jeungsando (증산도) is the most active overseas.[88]

There are also a number of small religious sects, which have sprung up around Gyeryongsan ("Rooster-Dragon Mountain", always one of Korea's most-sacred areas) in South Chungcheong Province, the supposed future site of the founding of a new dynasty originally prophesied in the 18th century (or before). Japanese Tenriism (천리교 Cheonligyo) also claims to have thousands of South Korean members.[89]

According to Andrew Eungi Kim, there was a rise of new religious movements in the late 1900s which account for about 10 percent of all churches in South Korea. According to Kim, this is the outcome of foreign invasions, as well as conflicting views regarding social and political issues. Many of the new religious movements are syncretic in character.[90]

Other religions

Bahá'í Faith

Baháʼí Faith was first introduced to Korea by an American woman named Agnes Alexander.

Confucianism

Only few contemporary South Koreans identify as adherents of Confucianism (유교 Yugyo). Korean intellectuals historically developed a distinct Korean Confucianism. However, with the end of the Joseon state and the wane of Chinese influence in the 19th and 20th century, Confucianism was abandoned. The influence of Confucian ethical thought remains strong in other religious practices, and in Korean culture in general. Confucian rituals are still practised at various times of the year. The most prominent of these are the annual rites held at the Shrine of Confucius in Seoul. Other rites, for instance those in honour of clan founders, are held at shrines found throughout the country.

Hinduism

Hinduism (힌두교 Hindugyo) is practiced among South Korea's small Indian, Nepali and Balinese migrant community. However, Hindu traditions such as yoga and Vedanta have attracted interest among younger South Koreans. Hindu temples in the Korea include the Sri Radha Shyamasundar Mandir in central Seoul, Sri Lakshmi Narayanan Temple in metropolitian Seoul, Himalayan Meditation and Yoga Sadhana Mandir in Seocho in Seoul, and Sri Sri Radha Krishna temple in Uijeongbu 20 km away on outskirt of Seoul.

Islam

Islam (이슬람교 Iseullamgyo) in South Korea is represented by a community of roughly 40,000 Muslims, mainly composed by people who converted during the Korean War and their descendants and not including migrant workers from South and Southeast Asia. The largest mosque is the Seoul Central Mosque in the Itaewon district of Seoul; smaller mosques can be found in most of the country's major cities. There are around a hundred thousand foreign workers from Muslim countries, particularly Indonesians, Malaysians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.[91]

Judaism

The Jewish existence in South Korea effectively began with the dawn of the Korean War in 1950. At this time a large number of Jewish soldiers, including the chaplain Chaim Potok, came to the Korean peninsula. Today the Jewish community is very small and limited to the Seoul Capital Area. There have been very few Korean converts to Judaism (유대교 Yudaegyo).

Shinto

During Japan's colonisation of Korea (1910-1945), given the suggested common origins of the two peoples, Koreans were considered to be outright part of the Japanese population, to be wholly assimilated. The Japanese studied and coopted native Sindo by overlapping it with their State Shinto (similar measures of assimilation were applied to Buddhism), which hinged upon the worship of Japanese high gods and the emperor's godhead. Hundreds of Japanese Shinto shrines were built throughout the peninsula.[92] This policy led to massive conversion of Koreans to Christian churches, which were already well ingrained in the country, representing a concern for the Japanese program, and supported Koreans' independence.[93] After the Allied forces defeated Japan in 1945, Korea was liberated from Japanese rule. As soon as the Shinto priests withdrew to Japan, all Shinto shrines in Korea were either destroyed or converted into another use.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Religion in South Korea. |

Footnotes

- Cognates of Japanese Shinto and Chinese Shendao.

- Another term is dangol (Hangul: 당골). The word mudang is mostly associated, though not exclusively, to female shamans due to their prevalence in the Korean tradition in recent centuries. This has brought to the development of other locutions for male shamans, including sana mudang (literally "male mudang") in the Seoul area or baksu mudang ("healer mudang"), shortened baksu, in the Pyongyang area. It is reasonable to believe that the word baksu is an ancient authentic designation for male shamans.[68]

References

- "성, 연령 및 종교별 인구 - 시군구" [Population by Gender, Age, and Religion - City/Country]. Korean Statistical Information Service (in Korean). 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Quinn, Joseph Peter (2019). "South Korea". In Demy, Timothy J.; Shaw, Jeffrey M. (eds.). Religion and Contemporary Politics: A Global Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 365. ISBN 978-1-4408-3933-7. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Pyong Gap Min, 2014.

- WIN-Gallup International: "Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism 2012" Archived 21 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kim Han-soo, Shon Jin-seok. 신자 수, 개신교 1위… "종교 없다" 56%. The Chosunilbo, 20/12/2016. Retrieved 02/07/2017.

- Ogata, Mamoru Billy (1984). A Comparative Study of Church Growth in Korea and Japan: With Special Application to Japan. Fuller Theological Seminary. p. 32 ff.

- Joon-sik Choi, 2006. p. 15

- Grayson, 2002. pp. 155-187

- Grayson, 2002. pp. 158-161

- Grayson, 2002. p. 158, p. 162

- Grayson, 2002. p. 163

- Lankov, Andrei. The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 0199390037. p. 9.

- Kendall, 2010. pp. 4-17

- Baker, 2008. pp. 4-5

- "Quality Data on Religion". The Association of Religion Data Archives. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- "The Republic of South Korea: Religious Adherents, 2010 (World Christian Database)". Association of Religion Data Archives. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Pollack, Detlef; Rosta, Gergely (2018). Religion and Modernity: An International Comparison. Oxford University Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0198801665.

- "시도/연령/성별 종교인구" [Population by Cities, Age, Gender, Religion]. Korean Statistical Information Service (in Korean). 1985. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "행정구역/성/연령별 종교인구" [Population of Religions by Region, Gender, Age]. Korean Statistical Information Service (in Korean). 1995. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "성/연령/종교별 인구 - 시군구" [Population by Gender, Age, and Religion - City/Country]. Korean Statistical Information Service (in Korean). 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Asia For Educators: Korea, 300 to 600 CE. Columbia University, 2009.

- Vermeersch, Sem. (2008). The Power of the Buddhas: the Politics of Buddhism during the Koryŏ Dynasty (918-1392). p. 3

- Grayson, 2002. pp. 120-138

- Tudor, 2012.

- Grayson, 2002. p. 137

- Grayson, 2002. p. 155

- Grayson, 2002. p. 157

- Grayson, 2002. pp. 157-158

- Grayson, 2002. p. 158

- Carl Young. Into the Sunset: Ch’ŏndogyo in North Korea, 1945–1950. On: Journal of Korean Religions, Volume 4, Number 2, October 2013. pp. 51-66 / 10.1353/jkr.2013.0010

- Kendall, 2010. p. 10

- Joon-sik Choi, 2006. p. 17

- Baker, 2008. p. 4

- Baker, 2008. p. 3

- Baker, 2003. p. 5

- South Korea National Statistical Office's 19th Population and Housing Census (2015): "Religion organisations' statistics". Retrieved 20 December 2016

- Buswell, Lee. 2007. p. 375

- Korean Buddhism has its own unique characteristics different from other countries, koreapost.com, Jun 16, 2019.

- Pye, Michael (2002). "Won Buddhism as a Korean New Religion". Numen. 49 (2): 113–141. doi:10.1163/156852702760186745. JSTOR 3270479.

- 안동근현대사 [Andong National: Modern and Contemporary history] (PDF). andong.go.kr (in Korean). 15 December 2010. p. 228. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2014.

문화관광부의 2005년 5월 자료에 따르면 우리나라에는 907개의 사찰이 있는데, 이를 종단별로 보면, 대한불교조계종 735개소(81%), 한국불교태 고종 102개소(11%), 대한불교법화종 22개소(2%), 선학원 16개소(2%), 대한불교원효종 5개소(1%), 기타 27개소(3%) 순이다.

- At Korean Wikipedia

- According to figures compiled by the South Korean National Statistical Office."인구,가구/시도별 종교인구/시도별 종교인구 (2005년 인구총조사)". NSO online KOSIS database. Archived from the original on 8 September 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- Kedar, Nath Tiwari (1997). Comparative Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0293-4.

- Religious Intelligence UK Report

- North Korea, about.com

- Choi Suk-woo. Korean Catholicism Yesterday and Today. On: Korean Journal XXIV, 8, August 1984. pp. 5-6

- Kim Han-sik. The Influence of Christianity. In: Korean Journal XXIII, 12, December 1983. pp. 5-7

- Kwon, Okyun (2003). Buddhist and protestant Korean immigrants: religious beliefs and socioeconomic aspects of life. LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-931202-65-7.

- Kim Ok-hy. Women in the History of Catholicism in Korea. In: Korean Journal XXIV, 8, August 1984. p. 30

- "Kim Ho Jik: Korean Pioneer". The Ensign. July 1988. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Seoul Korea". churchofjesuschrist.org. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- "LDS Church announces creation of 58 new missions". Deseret News. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Facts and Statistics, South Korea". LDS Newsroom. 31 December 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Matczak, Sebastian (1982). Unificationism: A New Philosophy and Worldview. New York, NY: New York Learned Publications.

- Moon, Sun Myung (2013). True Families: Gateway To Heaven. 4 West 43rd Street New York, NY: HSA-UWC. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-931166-31-7.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "'Moonies' launch political party in S Korea". iol.co.za. Sapa-AFP. 10 March 2003. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- Park, Chang-Won (10 June 2010). Cultural Blending in Korean Death Rites. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-4411-1749-6.

- George Minamiki (1985). The Chinese rites controversy: from its beginning to modern times. Loyola University Press. ISBN 978-0-8294-0457-9. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Mantienne, pp. 177-82.

- Marcel Launay; Gérard Moussay (24 January 2008). Les Missions étrangères: Trois siècles et demi d'histoire et d'aventure en Asie. Librairie Académique Perrin. pp. 77–83. ISBN 978-2-262-02571-7. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- Suh, Sharon A. (2004), Being Buddhist in a Christian World: Gender and Community in a Korean American Temple, University of Washington Press, p. 49, ISBN 0-295-98378-7

- Kwon, Okyun (2003). Buddhist and protestant Korean immigrants: religious beliefs and socioeconomic aspects of life. LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-931202-65-7.

- Used in: Chang Soo-kyung, Kim Tae-gon. Korean Shamanism – Muism. Jimoondang, 1998.

- Lee Chi-ran, p. 13

- Used in: Margaret Stutley. Shamanism: A Concise Introduction. Routledge, 2003.

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. p. 4

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. p. 5

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. pp. 3-4

- Joon-sik Choi, 2006. p. 21

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. p. 18

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. p. 17

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. pp. 5-12

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. p. 13

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. p. 21

- Sorensen, p. 19-20

- Jung Young Lee, 1981. pp. 17-18

- Andrew E. Kim (2000). "Korean Religious Culture and Its Affinity to Christianity" (PDF). Korea University, Sociology of Religion. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- Kendall, 2010. pp. 4-7

- http://www.koreana.or.kr/months/news_view.asp?b_idx=2244&lang=en&page_type=list

- http://www.koreana.or.kr/months/news_view.asp?b_idx=2243&lang=en&page_type=list

- Joon-sik Choi, 2006. pp. 17-18-19

- Sang-Hun, Choe (6 July 2007). "In the age of the Internet, Korean shamans regain popularity". New York Times.

- Lee, 1996. p. 109

- Lee, 1996. p. 105

- Lee, 1996. p. 110

- Baker, 2008. p. 118

- Baker, 2008. p. 85

- Baker, 2008, p. 986;

- Baker, 2008. p. 93

- Kim, Andrew Eungi (2002). "Characteristics of Religious Life in South Korea: A Sociological Survey". Review of Religious Research. 43 (4): 291–310. doi:10.2307/3512000. JSTOR 3512000.

- "Korea's Muslims Mark Ramadan". The Chosun Ilbo. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- Yi, Yong-sik (2010). Shaman Ritual Music in Korea. University of Minnesota. ISBN 1931897107. p. 11

- Korean Social Sciences Journal, 24 (1997). Korean Social Science Research Council. pp. 33-53

Sources

- Daniel Tudor. Korea: The Impossible Country. Tuttle Publishing, 2012. ISBN 0804842523

- Donald L. Baker. Korean Spirituality. University of Hawaii Press, 2008. ISBN 0824832574

- Donald L. Baker. Modernization and Monotheism: How Urbanization and Westernization Have Transformed the Religious Landscape of Korea. University of British Columbia. Published in: Sang-Oak Lee, Gregory K. Iverson, Pathways into Korean Language and Culture: Essays in Honor of Young-key Kim-Renaud. Pajigong Press, Seoul, 2003. pp. 471–507

- James H. Grayson. Korea - A Religious History. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 070071605X

- Joon-sik Choi. Folk-Religion: The Customs in Korea. Ewha Womans University Press, 2006. ISBN 8973006282

- Jung Young Lee. Korean Shamanistic Rituals. Mouton De Gruyter, 1981. ISBN 9027933782

- Laurel Kendall. Shamans, Nostalgias, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion. University of Hawaii Press, 2010. ISBN 0824833988

- Lee Chi-ran. Chief Director, Haedong Younghan Academy. The Emergence of National Religions in Korea.

- Pyong Gap Min, Development of Protestantism in South Korea: Positive and Negative Elements. On: Asian American Theological Forum (AATF) 2014, VOL. 1 NO. 3, ISSN 2374-8133

- Robert E. Buswell, Timothy S. Lee. Christianity in Korea. University of Hawaii Press, 2007. ISBN 082483206X

- Sang Taek Lee. Religion and Social Formation in Korea: Minjung and Millenarianism. Walter de Gruyter & Co, 1996. ISBN 3110147971

- Sorensen, Clark W. University of Washington. The Political Message of Folklore in South Korea's Student Demonstrations of the Eighties: An Approach to the Analysis of Political Theater. Paper presented at the conference "Fifty Years of Korean Independence", sponsored by the Korean Political Science Association, Seoul, Korea, July 1995.