Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) (Ottoman Turkish: إتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, romanized: İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti), later the Union and Progress Party (Ottoman Turkish: İttihad ve Terakki Fırkası, Turkish: Birlik ve İlerleme Partisi), was a secret revolutionary organization established as the society Committee of the Ottoman Union (Ottoman Turkish: İttihad-ı Osmanî Cemiyeti) in Constantinople (now Istanbul) on 6 February 1889 by a group of medical students of the Imperial Military School of Medicine. It was transformed into a political organisation (and later an official political party) by Bahattin Şakir, aligning itself with the Young Turks in 1906 during the period of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. In the West, the CUP was conflated with the wider Young Turk movement and its members were called Young Turks, while in the Ottoman Empire its members were known as İttihadists, or Unionists.

Union and Progress Party إتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی İttihad ve Terakki Fırkası | |

|---|---|

| |

| Secretary-General | Midhat Şükrü |

| Leaders after 1913 | "Three Pashas" |

| Founders | List

|

| Founded | 6 February 1889 (as an organisation) 1911 (as a political party) |

| Dissolved | 1 November 1918 |

| Succeeded by | Renewal Party Karakol organisation |

| Headquarters | Pembe Konak, Nuriosmaniye, Constantinople (now Istanbul), Ottoman Empire formerly in Salonica (now Thessaloniki) |

| Ideology | Constitutional monarchism Ottomanism (until 1913) Turkish nationalism (after 1913) Pan-Turkism (after 1913) Turanism (after 1913) Factions: Progressivism[1] Ultranationalism[1][2] Radicalism[1] Anti-communism[3] Authoritarianism[4][5] Islamism Secularism |

| Political position | Until 1913: Centre-right to right-wing After 1913: Far-right |

| Slogan | Hürriyet, Müsavat, Adalet ("Liberty, Equality, Justice") |

| Chamber of Deputies (1914) | 275 / 275

|

Begun as a liberal reform movement in the Ottoman Empire, the organization was persecuted by Abdulhamid II's autocratic government for its calls for democratisation and reform in the empire. In 1908, the CUP forced Abdulhamid to reinstate the constitution of 1876 in the Young Turk Revolution, thus inaugurating the empire's Second Constitutional Era. The CUP's rival was the Liberal Union, another Young Turk party calling for federalization and decentralization of the empire, in opposition to the CUP's desire of a centralized and unitary Turkish dominated Ottoman Empire.

The CUP consolidated its power at the expense of the Liberal Union in the 1912 "Election of Clubs" and the 1913 Raid on the Sublime Porte, while also growing increasingly more splintered, volatile and, after attacks on the empire's Turkish citizens during the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, nationalistic. After the 1913 coup, Union and Progress created a one party state within the Empire, with major decisions ultimately being decided in the party's Central Committee. Its three leaders, Talât Pasha, Enver Pasha, and Cemal Pasha, known as the Three Pashas, gained de facto rule over the Ottoman Empire. With the help of their paramilitary, the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization), the Union and Progress Party regime enacted policies of Turkification resulting in the Late Ottoman Genocides, which includes the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian Genocides.

At the end of World War I, most of its members were court-martialled and imprisoned by the sultan Mehmed VI with support from the Allied powers and a rehabilitated Liberal Union. In 1926, remaining members of the organisation were executed in Turkey after the trials for the attempted assassination of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Members who survived continued their political careers in Turkey as members of the Republican People's Party (Turkish: Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi)—founded by Atatürk—and other political parties in Turkey.

Name

Committee of Union and Progress was an umbrella name for different underground factions, some of which were generally referred to as the Young Turks. The name was officially sanctioned to a specific group in 1906 by Bahattin Şakir.

History

Background

During the 19th century the Ottoman Empire's Christian minorities achieved significant economic advancement in contrast to its Muslim subjects. This was due to external patronage from the European powers, which Muslims were not given access to. Therefore Tanzimat reforms (1839 - 1876) were undertaken to not only modernize the Ottoman Empire, but to also nation build a cohesive Ottoman national identity centered around national pride in the House of Osman instead of national pride in an ethno-religious group. This would be accomplished through reforms of centralization.

Abdulhamid II ascended to the throne in 1876 during the height of this period of reform in the Ottoman Empire. One of Abdulhamid's first acts as sultan was transforming the Ottoman Empire into a constitutional monarchy with the introduction of the Kanûn-u Esâsî, thus starting the Empire's first short experience with democracy: the First Constitutional Era. However, in the aftermath of Russian invasion in 1877-1878, Abdulhamid used his constitutionally given power as sultan to suspend parliament and the constitution and rule the empire as an autocrat, emphasizing the empire's Islamic character and his position as Caliph as an ideology. To many in the empire, the war against Russia between 1877 and 1878 was traumatic, as the Russian army almost captured Constantinople while the war also saw the expulsion and massacres of many Balkan Muslims. The new status quo was the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, which saw the independence of many Balkan nations and the loss of the six eastern vilayets. When the Empire declared bankruptcy in 1881 the Ottoman economy came under the control of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, an institution owned by the European powers designed to manage the Empire's finances. Though Abdulhamid justified his autocracy to keep the empire from collapsing, many found it hypocritical of Abdulhamid to bow to foreign pressure by conceding sovereignty, land, and the economy to western powers.

The combination of European control over Ottoman finances and Ottoman Christian domination in the Ottoman economy resulted in much anti-Christian xenophobia in its Muslim subjects. Ottoman Christians, especially Ottoman Armenians, started to increasingly feeling insecure in their position as Ottoman subjects after these sentiments manifested in the Hamidian massecres (1894-1896), and started demanding autonomy from the government. Dr. Mehmed Reşid, a founder of the future CUP, wrote:

The Ottoman element is shrinking. Ottoman land is disappearing piece by piece. Of this, we are witnesses, and we know who the culprites are. In order to make all this evil disappear, in order to rescue our working village dwellers and feed them well, we have declared war on these libertines, these tyrants, these enemies of the fatherland. [6]

It was in this context the Young Turks movement was formed as an opposition group by Ottoman intellectuals against Abdulhamid's absolutist regime, united by a common sentiment that the current Hamidian regime was unsustainable and that modernization had to occur through Abdulhamid's overthrow and a reintroduction of the 1876 constitution. However there would soon be a division in the Young Turks movement on how the Empire should be reformed.

Origins (1889 - 1906)

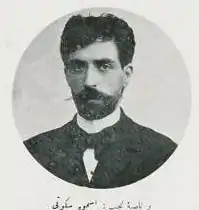

The Committee of Ottoman Union, soon the Committee of Union and Progress, was founded in 1889 by Ibrahim Temo, Dr. Mehmed Reşid, Abdullah Cevdet, İshak Sükuti, Ali Hüseyinzade, Kerim Sebatî, Mekkeli Sabri Bey, Dr. Nazım Bey, Şerafettin Mağmumi, Cevdet Osman and Giritli Şefik, all of whom were medical students of the Imperial Military School of Medicine in Constantinople.[7][8][9] As they called for a reinstatement of the constitution and Ottomanism which would be achieved by overthrowing Abdulhamid II for one of his brothers, either future sultan Mehmed V or former sultan Murad V; the organization aligned itself with the Young Turks movement. It rapidly gained membership, but after a failed putch against Abdulhamid in 1895, the organization was repressed and most of its members fled into exile to Paris, London, Geneva, Bucharest, and British occupied Egypt.[10] After the Ottoman Empire's victory over Greece in 1897 Abdulhamid attempted to use the prestige he gained from the victory to coerce the exiled Young Turks network back into his fold. Cevdet Bey and Sükuti Bey accepted, leaving Ahmet Rıza in Paris as leader of the exiled Young Turks network and the CUP.[10] Rıza Bey was a more moderate and conservative member of the CUP as well as an avid follower of positivist theory. Rıza called for Abdulhamid's overthrow and the reinstatement of the constitution, but also a more centralized and sovereign Turkish dominated Ottoman Empire without European influence.[11]

In 1901, members of the Ottoman dynasty Damat Mahmud Pasha and his sons Sabahaddin and Lütfullah defected from Abdulhamid and fled to Europe to join the Young Turks. Prince Sabahaddin, inspired by Anglo-Saxon values of capitalism, liberty, and moderation, would go on to found the League for Private Initiative and Decentralization [tr] calling for a more decentralized and federal Ottoman Empire in opposition to Rıza's CUP. Prince Sabahaddin believed that the only reason why separatist movements existed amongst Ottoman Armenians was due to the oppressive policies of Abdulhamid II, and if only the empire would treat its Armenian minority better, then Armenians would become loyal Ottomans. Sabahaddin's new group created a division within the exiled Young Turks which he attempted to fuse by organizing the First Congress of Ottoman Opposition in 1902, Paris, however no progress in cooperation came about. This deepened the rivalry between Sabahaddin's group and Rıza's CUP.

Revolutionary Era: 1906–1908

In September 1906, the Ottoman Freedom Society (Turkish: Osmanlı Hürriyet Cemiyeti) was formed as another secret Young Turk organization based in Salonica (modern Thessaloniki), though with more emphasis on Muslim unity, with Mehmet Talât Bey, İsmail Enver Bey, Ahmed Cemal Bey, Mustafa Rahmi Bey, and Dr. Midhat Şükrü being its core.[12] Especially from 1906 onward, the OFS enjoyed great success in recruiting army officers from the Ottoman Third Army based in Macedonia.[13][12] Officers of the Third Army believed the state needed drastic reforms in order to survive and bring peace to the violent region. This made the appeal of joining imperially biased revolutionary secret societies especially seductive to them.[13] Most of the Ottoman officers serving in the CUP were junior officers, but the widespread belief that the empire needed reforms led the senior officers of the Third Army to turn a blind eye to the fact that most of the junior officers had joined the CUP.[14] Under Talât's initiative, the OFS merged with Rıza's Paris-based CUP in September 1907.[12] After the Young Turk Revolution, the militant OFS faction within the CUP would gradually take over the organisation and the party from within.

In the Second Congress of Ottoman Opposition in 1907 Rıza and Sabahaddin were finally able to put their differences aside and signed an alliance, declaring that Abdulhamid had to be deposed and the regime replaced with a representative and constitutional government by all means necessary.[15][16] Included in this alliance was another faction, the Armenian nationalist Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnak) (Dashnaktsutyun). ARF member Khachatur Maloumian officially signed the alliance, with the hope that decentralizing reforms could be conceded to Ottoman Armenians once the Young Turks took power (even though the CUP's core mantra was centralization). However Ahmet Rıza eventually pulled out of the tripartide agreement, and this alliance played no critical role in the upcoming revolution.[17]

Intending to emulate revolutionary nationalist organizations like the Bulgarian IMRO and Armenian Dashnak, the CUP would build an extensive cell based organisation, having a presence in towns throughout European Turkey. By comparison, the CUP was noticeably absent from intellectual circles and army units based in Anatolia and the Levant.[15] Under this umbrella name, one could find ethnic Albanians, Bulgarians, Arabs, Serbians, Jews, Greeks, Turks, Kurds, and Armenians united by the common goal of changing the Abdulhamid's totalitarian regime. The CUP professed to be fighting for the restoration of the 1876 constitution, but its internal organisation and methods were intensely authoritarian, with its cadres expected to strictly follow orders from the organization's Central Committee.[18]

Joining the early CUP was by invitation only, and those who did join had to keep their membership secret.[14] Those who joined the CUP had to swear a sacred oath with the Koran in the right hand and a sword or dagger in the left hand to unconditionally obey all orders from the CUP Central Committee; to never reveal the CUP's secrets and to keep their own membership secret; to be willing to die for the fatherland and Islam at all times; and to follow orders from the Central Committee to kill anyone whom the Central Committee wanted to see killed, including one's own friends and family.[14] The penalty for disobeying orders from the Central Committee or attempting to leave the CUP was death.[19] To enforce its policy, the Unionists had a select group of especially devoted party members known as the fedâiin, whose job was to assassinate those CUP members who disobeyed orders, disclosed its secrets, or were suspected of being police informers.[18]

Young Turk Revolution

Sultan Abdulhamid II persecuted the members of the CUP in an attempt to hold on to absolute power, but was forced to reinstate the Ottoman constitution of 1876, which he had originally suspended in 1878, after threats to overthrow him by the CUP in the 1908 Young Turk Revolution. The revolution had been sparked by a summit in July 1908 in Reval, Russia (modern Tallinn, Estonia) between King Edward VII of Great Britain and the emperor Nicholas II of Russia. Popular rumour within the Ottoman Empire had it that during the summit a secret Anglo-Russian deal was signed to partition the Ottoman Empire. Though this story was not true, the rumour led the CUP (which had many army officers as its members) to act. Enver Bey and Ahmet Niyazi Bey were dispatched to the Albanian hinterlands to organise militias in support of a constitutionalist revolution. The CUP threatened Hayri Pasha, field marshal of the Third Army, into passive cooperation, while also assassinating Şemsi Pasha, Abdulhamid's right hand man who he sent to suppress the revolt in Macedonia.[20] At this point, the mutiny which originated in the Third Army in Salonica took hold of the Second Army based in Adrianople (modern Edirne) as well as Anatolian troops sent from Izmir. Under pressure of being deposed, on July 24, 1908 Abdulhamid capitulated and reinstated the 1876 Ottoman Constitution to great jubilation. Post-revolution, Enver and Niyazi would be hailed throughout the Empire and its people's as "heroes of the revolution".

The CUP succeeded in reestablishing democracy and constitutionalism in the Ottoman Empire but refused to take direct power after the revolution, choosing instead to monitor the politicians from the sidelines. This was done because most of its members were younger and held little to no skill in statecraft, while the organization itself held little power outside of Rumelia.[21] The CUP decided to continue its clandestine nature by keeping its members secret but sent to Constantinople a delegation of seven high ranking Unionists known as the Committee of Seven, including Cemal Bey, Talât Bey, and Mehmed Cavit Bey. After the revolution, power was shared between the palace (Abdulhamid), the Sublime Porte, and the CUP, who's Central Committee was still based in Salonica, and now represented a powerful deep state faction.[22]

With the reestablishment of the constitution and parliament, most Young Turk organizations turned into political parties, including the CUP. However, after meeting of the goal reinstating the constitution, in the absence of this uniting factor, the CUP and the revolution began to fracture and different factions began to emerge. Prince Sabahaddin would found the Ottoman Liberty Party and later in 1911 the Freedom and Entente Party, both commonly referred to as the Liberal Union and its members as Liberals by Ottoman historians. Ibrahim Temo and Abdullah Cevdet, two original founders of the CUP, would found the Ottoman Democratic Party [tr] in February 1909. Ahmet Rıza who returned to the capital from his exile in Paris became president of the Chamber of Deputies, the parliament's lower house, and would gradually distance himself from the organisation as it became more nationalistic.

Second Constitutional Era: 1908–1913

In the Ottoman general election of 1908 the CUP captured only 60 of the 275 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, despite its leading role in the revolution. Other parties represented in parliament at this time included Armenian Dashnak and Hunchak parties (four and two members respectively) and the main opposition, Prince Sabahaddin's Ottoman Liberty Party.

An early victory of the CUP over Abdulhamid happened on 1 August, when instead of Abdulhamid assigning ministries himself he was forced to assign ministries according to the Central Committee's will.[23] Four days later, the CUP told the government that the current Grand Vizier (at this point a prime ministerial title under the constitution) Mehmed Sait Pasha was unacceptable to them, and had Kâmil Pasha appointed Grand Vizier.[24]

On 16 August 1909, the government passed the "Law of Associations", which banned ethnically based political parties.[25] A month later, the government passed the "Law for the Prevention of Brigandage and Sedition", which created "special pursuit battalions" to hunt down guerrillas in Macedonia, made it illegal for private citizens to own firearms and imposed harsh penalties for those who failed to report the activities of guerrillas.[25] At the same time, the government expanded the educational system by founding new schools while at the same time announcing that henceforward Turkish would be the only language of instruction.[25] On 14 February 1909 Kâmil proved to be too independent for the CUP and was forced to resign. He was replaced by Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha who was more partial towards the CUP.[26]

A sign of how the CUP power worked occurred in February, when Ali Haydar who had just been appointed ambassador to Spain went to the Sublime Porte to discuss his new appointment with the Grand Vizier Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha, only be to be informed by the Grand Vizier he needed to confer with a man from the Central Committee who was due to arrive shortly.[26]

1909 Counter Coup and aftermath

In 1909 a reactionary mob revolted in Istanbul against the constitutional system in support of the restoration of Abdulhamid's absolutist rule, securing Constantinople. The constitution was again suspended in favor of sharia and the Unionists were driven out of Constantinople. However Unionist factions within in the army lead by Mahmud Şevket Pasha formed the "Army of Action" (Turkish: Hareket Ordusu) which culminated in the 31 March Incident. Some lower ranking Unionist officers within the army included Enver Bey, Niyazi Bey, and Cemal Bey as well as future presidents of the Republic of Turkey Mustafa Kemal Bey and İsmet Bey.[27] Istanbul was taken back within a few days, order was restored through many courts marshals, and the constitution was reinstated for the third and final time.

The consequences of the failed countercoup massively shifted fortune in the CUP's favor. Abdulhamid II was deposed via a fatwa issued by the Shaykh-al-Islam and a unanimous vote of the Ottoman Parliament. Abdulhamid's younger brother, Reşat, replaced him and took the name Mehmed V, committing to the role of a constitution monarch and figurehead of the future CUP party-state. Due to Prince Sabahaddin's Ottoman Liberty Party's reluctant support for the counter revolution, the party would be banned. The Central Committee expected more influence in the government for their role in foiling the countercoup, and maneuvered Mehmet Cavit into the Ministry of Finance in June, becoming the first Unionist affiliated minister in the government. Two months later, Talât Bey took Ferid Pasha's position as Minister of Interior.[28] In 1909 many amendments to the constitution were passed through to empower the parliament at the expense of the sultan.

CUP and the ARF held a strong alliance throughout the Second Constitutional Era, with their cooperation dating back to the Second Congress of Ottoman Opposition of 1907; as both were united in overthrowing the Hamidian regime for a constitutional one.[15] During the countercoup, massacres against Ottoman Armenians in Adana occurred that was facilitated by members of the local CUP branch, straining the alliance between the CUP and Dashnak. The committee made up for this by nominating Ahmet Cemal, an influential Unionist from the old Ottoman Freedom Society and Committee of Seven, as governor of Adana.[29] Cemal Bey restored order, providing compensation to victims and bringing justice to the perpetrators, which mended the two parties relations.[29]

By the end of 1909, the CUP was an organization with 850,000 members and 360 branches spread across the empire.[30]

Near fall from power

Mahmud Şevket Pasha's role in deposing Abdulhamid for good gave him considerable power; he became of martial-law commander of Constantinople, inspector of the First, Second, and Third armies, as well as Minister of War. Mahmud Şevket Pasha, representing the military, would often butt heads with the CUP as he represented the only opposition to the CUP other than the small Ottoman Democratic Party [tr] after the 31 March Incident. In February 1910 several parties splintered from the CUP, including the People's Party, Ottoman Committee of Alliance, and the Moderate Liberty Party [tr].[31]

In September 1911, Italy submitted an ultimatum containing terms clearly meant to inspire rejection, and following its duly expected rejection, invaded Tripolitania.[32] The Unionist officers in the army were determined to resist the Italian aggression, and the parliament had succeeded in passing the "Law for the Prevention of Brigandage and Sedition", a measure ostensibly intended to prevent insurgency against the central government, which assigned that duty to newly created paramilitary formations. These later came under the control of the Special Organisation (Ottoman Turkish: تشکیلات مخصوصه, romanized: Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa), which was used to conduct guerrilla operations against the Italians in Libya.[33] Those who once served as fedâiin assassins during the years of underground struggle were often assigned as leaders of the Special Organisation.[18] The ultra-secretive Special Organisation answered to the Central Committee, but in the future worked closely with the Ministry of War and Ministry of Interior.[34] A great many including Enver, his younger brother Nuri, Mustafa Kemal, Süleyman Askerî, and Ali Fethi all departed to Libya to fight the Italians.[35] With many of the Unionist officers in Libya, this weakened the power of the CUP and the army at home. As a consequence of the Italian invasion, İbrahim Hakkı Pasha's Unionist government collapsed and two more parties splintered from the CUP: the New Party, and the Progress Party.[36] The CUP was forced into a coalition government with some minor parties under Mehmed Sait Pasha.[36]

In spring 1911 a joint council between the CUP, at this point a political party known as the Union and Progress Party, and Dashnak drew up plans for a bipartisan reform package for the eastern provinces which would be administered in cooperation with European inspectorates.[37] This reform package would turn out to be stillborn, being abandoned by October 1914 as the future Ittihadist (Unionist) regime embraced its Turkish nationalist character at the expense of Ottomanism.

As a result of the "Law of Associations", which shut down ethnically based organisations and clubs, by the time of the second general election in April 1912, the smaller parties and ethnic parties had coalesced around the big tent Freedom and Accord Party, also known as the Liberal Union by Ottoman historians, immediately attracting 70 deputies to its ranks. Dashnak and the Union and Progress Party campaigned for the elections under an electoral alliance. Alarmed at the success of Liberal Union and increasingly radicalised, Union and Progress won 269 of the 275 seats in parliament through electoral fraud and violence, which led to the election being known as the "Election of Clubs" (Turkish: Sopalı Seçimler), leaving the Liberal Union just six seats.[38][39] In most republics, this is the margin required for wholesale transformation of the constitution, but the Ottoman Empire was a constitutional monarchy, although it is unlikely Sultan Mehmed V could have prevented the revision of the constitution. Though the ARF received ten seats from the CUP's lists, Dashnak terminated the alliance as they expected more reforms from the CUP as well as more support for their candidates to be elected.[39]

In May 1912, colonel Mehmed Sadık separated from the CUP and organized a group of pro-Liberal Union officers in the army calling themselves the Saviour Officers Group, which demanded the immediate dissolution of the Unionist dominated parliament on July 11.[40][41] The fraudulent electoral result of the "Election of Clubs" had badly hurt the popular legitimacy of the CUP, and faced with widespread opposition and Mahmud Şevket Pasha's resignation as Minister of War in support of the officers, Sait Pasha's Unionist government resigned on 9 July 1912.[42] It was replaced by Ahmed Muhtar Pasha's "Great Cabinet" that deliberately excluded the CUP by being made up of older ministers, many of which were associated with the old Hamidian regime.[40] On 5 August 1912, Muhtar Pasha's government shuttered the Unionist dominated parliament. For the moment, the CUP had been driven from power and risked being shut down by the government.

With the CUP out of power, the party challenged Muhtar Pasha's government to a jingoistic game of pro-war populism against the Balkan states by utilizing its still powerful propaganda network.[43] Unbeknownst to the CUP, the Sublime Porte, and most international observers, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece were already preparing themselves for a war against the Empire in an alliance known as the Balkan League.[43] On 28 September 1912, the Ottoman army conducted military maneuvers on the Bulgarian border, to which Bulgaria responded by mobilizing.[43] On 4 October the CUP organized a pro-war rally in Sultanahmet Square.[44] Finally on 8 October, Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire, starting the First Balkan War, with the rest of its allies joining in during the week. The Ottoman Empire and Italy concluded their war so that the Empire could focus on the Balkan states with the Treaty of Ouchy, in which Tripolitania was annexed and the Dodecanese were occupied by Italy. This rest of the parliamentary session proved to be very short due to the outbreak of the First Balkan War; sensing the danger, the government won passage of a bill conscripting dhimmis into the army. This proved too little and too late to salvage Rumelia; Albania, Macedonia, and western Thrace was lost, Edirne was put under siege, and Constantinople was in serious risk of being overrun by the Bulgarian army (First Battle of Çatalca). Edirne was a symbolic city, as it was an important city in Ottoman history, serving as the Empire's third capital for nearly one hundred years, and together with Salonica represented Europe's Islamic heritage.

Muhtar Pasha's government resigned on the 29th of October following total military defeat in Rumelia for Kâmil Pasha's return, who was closer to the Liberal Union and keen on dismantling the CUP once and for all. With the loss of Salonica to Greece the CUP was forced to relocate its Central Committee to Istanbul, however by mid-November the new headquarters would be shut down by the government and its members were forced into hiding.[45] With the government signing a truce with the Balkan League and an imminent ban of the CUP by Kâmil Pasha's government, the CUP was now radicalized and willing to do all it could do to safeguard Turkish interests and as soon as possible.

1913 Coup, assassination, and aftermath

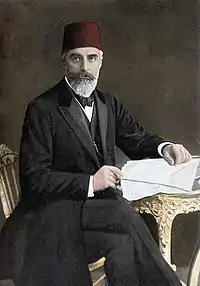

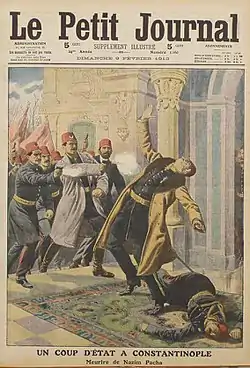

Grand Vizier Kâmil Pasha and his Minister of War Nazım Pasha (not to be confused with Dr. Nazım Bey, a high-ranking member of the CUP and original founder who was part of its Central Committee) became targets of the CUP, which overthrew them in a military coup d’état known as the Raid on the Sublime Porte on 23 January 1913. During the coup Kâmil Pasha was forced to resign as Grand Vizier at gunpoint and a Unionist officer Yakub Cemil killed Nazım Pasha.[46] The coup was justified under the grounds that Kâmil Pasha was about to "sell out the nation" by agreeing to a truce in the First Balkan War and giving up Edirne.[47] The intention of the new leadership, dominated by a group consisting of high ranking Unionists consisting of Mehmet Talât Bey, İsmail Enver Bey, Ahmet Cemal Bey, and Halil Menteşe Bey, under Mahmud Şevket Pasha's premiership (who reluctantly accepted the role), was to break the truce and renew the war against Bulgaria.[47] The CUP did not fully take over of the government; only three Unionist ministers were appointed into the new government, including Talât Bey returning to his post as Minister of Interior, a job he would keep until 1917.

The immediate aftermath of the coup resulted in a much more severe state of emergency than previous governments had ever implemented. Ahmet Cemal in his new capacity as military commander of Constantinople would be responsible for arresting many and heavily stifling opposition.[48]

The pro-war regime immediately withdrew the Empire's delegation from the London conference on the same day it took power. The first task of the new regime was to found the Committee for National Defence on 1 February 1913 which was intended to mobilize the resources of the empire for an all-out effort to turn the tide.[47] On 3 February 1913 the war resumed. The new government staked a daring operation in which the 10th Army Corps were to make an amphibious landing at the rear of the Bulgarians at Şarköy while the Straits Composite Force was to break out of the Gallipoli peninsula.[49] The operation failed due to a lack of co-ordination with heavy losses.[49] Following reports that the Ottoman army had at most 165,000 troops to oppose the 400,000 of the League army together with news that morale in the army was poor due to Edirne's surrender to Bulgaria on 26 March, the pro-war regime finally agreed to an armistice on 1 April 1913 and signed the Treaty of London on May 30th, acknowledging the loss of all of Rumelia except for Constantinople.[50]

News of the failure to rescue Rumelia by the CUP prompted the organization of a countercoup by Kâmil Pasha that would terminate the CUP and bring the Liberal Union back into power.[51] Kâmil Pasha would be put under house arrest on May 28, however the conspiracy would continue and aim to assassinate Grand Vizier Şevket Pasha and major Unionists.[51] On June 11, only Mahmud Şevket Pasha would be assassinated; by one of Nazım Pasha's relatives as revenge for being associated with Nazım's murderers' party. The CUP took full control over the empire after Mahmud Şevket Pasha's assassination. The Union and Progress Party became the empire's sole legal political party. All provincial and local officials reported to "Responsible Secretaries" chosen by the party for each vilayet. Mehmed V appointed Sait Halim Pasha, who was loosely affiliated with the CUP, to serve as Grand Vizier until Talât Pasha replaced him in 1917. A courts marshal sentenced to death 16 Liberal Union leaders, including Prince Sabahaddin who was sentenced in absentia, as he already fled to Geneva in exile.[51] Also in April, Niyazi Bey, one of the heros of the Young Turk Revolution who had since distanced himself from the CUP, would be killed by the hands of unknown gunmen.

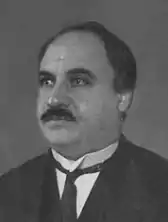

The new regime was dominated by a triumvirate that turned the Ottoman Empire into a one party state of Union and Progress, known in history as the Three Pashas Triumvirate. The triumvirate consisted of Talât Pasha, Enver Bey, and Cemal Bey (Enver and Cemal would soon become Pashas). Some say Halil Bey was a forth member of this clique. Historian Hans-Lukas Kieser asserts that this state of rule by the Three Pashas triumvirate is only accurate for the year 1913–1914, and that Talât Pasha would increasingly become a more central figure within the Union and Progress party state, especially once he stepped down as Minister of Interior to became both Grand Vizier and foreign Minister in 1917.[52] Alternatively, it would also be accurate to call the Unionist regime a clique or even an oligarchy, as many prominent Unionists held some form of de jure or de facto power. Other than the Three Pashas and Halil Bey, personalities such as Dr. Nazım, Bahattin Şakir, Ziya Gökalp, and the party's secretary general Midhat Şükrü also dominated the Central Committee without formal positions in the Ottoman government. This one party state of the Union and Progress regime of the Ottoman Empire would last from 1913 to the empire's surrender in World War I in October 1918.

On 20 July 1913, following the outbreak of the Second Balkan War, the Ottomans attacked Bulgaria and on 21 July 1913 Kaymakam Enver retook Edirne from Bulgaria, making him a national hero.[53] After taking back Edirne, the Special Organisation of Unionist fedais and junior officers were sent to organise the Turkish population of Thrace to wage guerrilla warfare against the Bulgarians.[54] By the terms of the Treaty of Bucharest in September 1913, the Ottomans regained some of the land lost in Thrace during the First Balkan War.[53]

Road to World War I: 1913-1914

To the CUP, the loss of Rumelia reduced the need for Ottomanism, while defeat in the First Balkan War had showed that the empire's Christian population were potential fifth columns. Lack of action by the European powers in upholding the integrity of the Empire and the status quo of the Berlin Treaty during the Balkan wars meant that the Turks were on their own. The reconquest of Edirne was a great confidence booster to the CUP, due to the European powers demanding Edirne's surrender to Bulgaria in the First Balkan War.[55] The CUP lost much respect for the European powers and all these factors allowed for a more public display of Turkish nationalism at the expense of Ottomanism.[56] This abandonment of Ottomanism was much more feasible due to the new borders of the Empire after the Balkan Wars inflating the proportion of Turks and especially Muslims of the empire and in the parliament at the expense of Christians.

Nationalistic rhetoric

Right from the start, the triumvirate which dominated the CUP did not accept the outcome of the Balkan wars as final, and a major aim of the new regime was to take back all of the territory which had been lost.[57] Enver Bey made a speech in 1913 in which he said:

How could a person forget the plains, the meadows, watered with the blood of our forefathers, abandon those places where Turkish raiders had hidden their steeds for six hundred years, with our mosques, our tombs, our dervish retreats, our bridges, and our castles, to leave them to our slaves, to be driven out of Rumelia to Anatolia, this was beyond a person's endurance. I am prepared to gladly sacrifice the remaining years of my life to take revenge on the Bulgarians, the Greeks and the Montenegrins.[58]

Another Unionist stated that "The people of the Balkans turned Rumelia into a slaughterhouse of the Turks". He added that the entire movement was obsessed with taking back Rumelia (the Ottoman name for the Balkans), and to have revenge for the humiliating defeat of 1912. A school textbook from 1914 captured the burning desire for revenge:

In the year 1330 [1912] the Balkan states allied against the Ottoman government... In the meantime, they shed the blood of many innocent Muslim and Turkish people. Many women and children were massacred. Villages were burnt down. Now in the Balkans under every stone, there lay thousands of dead bodies, with eyes and stomachs carved out, awaiting revenge... It is our duty to our fatherland, as sons of the fatherland, to restore our stolen rights, and to work to take revenge for the many innocent people whose blood were shed in abundance. Then let us work to instil that sense of revenge, love of fatherland and sense of sacrifice for it.[59]

In the aftermath of the First Balkan War with the humiliating loss of Rumelia together with thousands of refugees from Rumelia bearing tales of atrocities committed by the Greek, Montenegrin, Serb and Bulgarian forces, a marked anti-Christian and xenophobic mood settled in amongst many Ottoman Muslims.[58] The CUP encouraged boycotts against Austrian, Bulgarian, and Greek businesses, but after 1913 also against the empire's own Christian and Jewish citizens.[60]

The decreased importance of Ottomanism in reaction to the perception of a Christian fifth column, as well as the suspicion directed against other Muslim groups such as Arabs and Kurds after it was shown that Muslim Albanians did not become any more loyal to the empire after the Young Turk Revolution, resulted in the new regime starting to glorify the "Turkish race". Particular attention was paid to Turan, the mythical homeland of the Turks that was located north of China.[61] A much greater emphasis was put on Turkish nationalism with the Turks being glorified in endless poems, pamphlets, newspaper articles and speeches as a great warrior nation who needed to recapture their former glory.[62] The chief ideologue of the CUP, Ziya Gökalp, complained in a 1913 essay that "the sword of the Turk and likewise his pen have exalted the Arabs, the Chinese and the Persians" rather than themselves and that the modern Turks "needed to turn back to their ancient past".[63] Gökalp argued it was time for the Turks to start following such great "Turanian" heroes as Attila, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane the Great and Hulagu Khan.[61] As such, the Turks needed to become the dominant political and economic group within the Ottoman Empire while uniting with all of the other Turkic peoples in Russia and Persia to create a vast pan-Turkic state covering much of Asia and Europe.[63] In his poem "Turan", Gökalp wrote: "The land of the Turks is not Turkey, nor yet Turkestan. Their country is the eternal land: Turan".[63] The pan-Turanian propaganda was significant for not being based upon Islam, but was rather a call for the unity of the Turkic peoples based upon a shared history and supposed common racial origins together a pan-Asian message stressing the role of the Turkic peoples as the fiercest warriors in all of Asia. The CUP planned on taking back all of the territory that the Ottomans had lost during the course of the 19th century and under the banner of pan-Turkic nationalism to acquire new territory in the Caucasus and Central Asia.[64] This was the motivation for the Ottoman Empire's entry into World War I, the "pan-Turkic" ideology of the party which emphasized the Empire's manifest destiny of ruling over the Turkic people of central Asia once Russia was driven out of that region. Notably, two of the Three Pashas, Enver Pasha and Cemal Pasha, would in fact die in the Soviet Union leading Muslim anti-communist movements years after the Russian Revolution and the Ottoman defeat in World War I.

The first part of the plan for revenge was to go on a massive arms-buying spree, buying as many weapons from Germany as possible while asking for a new German military mission to be sent to the empire, which would not only train the Ottoman army, but also command Ottoman troops in the field.[65] In December 1913, the new German military mission under the command of General Otto Liman von Sanders arrived to take command of the Ottoman army; in practice, Enver who was determined to uphold his own power did not allow the German officers the sort of wide-ranging authority over the Ottoman army that the German-Ottoman agreement of October 1913 had envisioned.[66] At the same time, the Unionist government was seeking allies for the war of revenge it planned to launch as soon as possible. Ahmet Izzet Pasha, the Chief of the General Staff recalled: "... what I expected from an alliance based on defence and security, while others’ expectations depended upon total attack and assault. Without doubt, the leaders of the CUP were anxiously looking for ways to compensate for the pain of the defeats, which the population blamed on them."[67]

Right from the time of the 1913 coup d’état, the new government planned to wage a total war, and wished to indoctrinate the entire Turkish population, especially the young people, for it.[68] In June 1913, the government founded the Turkish Strength Association, a paramilitary group run by former army officers which all young Turkish men were encouraged to join.[69] The Turkish Strength Association featured much physical exercise and military training intended to let the Turks become the "warlike nation in arms" and ensure that the current generation of teenagers "who, in order to save the deteriorating Turkish race from extinction, would learn to be self-sufficient and ready to die for fatherland, honour and pride".[70] Besides for engaging in gymnastics, long-distance walking, running, boxing, tennis, football jumping, swimming, horse-riding, and shooting practice, the Turkish Strength Association handed out free medical books, opened dispensaries to treat diseases like tuberculosis and ran free mobile medical clinics.[70] In May 1914, the Turkish Strength Association was replaced with the Ottoman Strength Clubs, which were very similar except for the fact that the Ottoman Strength Clubs were run by the Ministry of War and membership was compulsory for Turkish males between the ages of 10–17.[71] Even more so than the Turkish Strength Association, the Ottoman Strength Clubs were meant to train the nation for war with an ultra-nationalist propaganda and military training featuring live-fire exercises being an integral part of its activities.[71] Along the same lines was a new emphasis on the role of women, who had the duty of bearing and raising the new generation of soldiers, who had to raise their sons to have "bodies of iron and nerves of steel".[72] The CUP created a number of semi-official organisations such as the Ottoman Navy League, the Ottoman Red Crescent Society and the Committee for National Defence that were intended to engage the Ottoman public with the entire modernisation project, and to promote their nationalist, militaristic ways of thinking amongst the public.[73] Reflecting Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz Pasha's influence, especially his "nation in arms" theory, the purpose of the society under the new regime was to support the military.[72]

In January 1914, Enver Bey would be appointed Minister of War, supplanting the calmer Ahmet Izzet Pasha, which made Russia, especially its Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov, greatly suspicious. Absent the wartime atmosphere, the CUP did not purge minority religions from political life; at least 23 Christians joined it and were elected to the third parliament in 1914, in which the Union and Progress Party was the only contender.

An extensive purge of the army was carried out in January 1914 with about 1,100 officers including 2 field marshals, 3 generals, 30 lieutenant-generals, 95 major-generals and 184 colonels whom Enver had considered to be inept or disloyal forced to take early retirement.[74]

Early acts of demographic engineering

Many Unionists were traumatized from the outcome of the Macedonian Question and the loss of most of Rumelia. The winners of the First Balkan War and the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish war applied anti-Muslim ethnic cleansing measures against its citizens, which the CUP would react with similar fever against the Empire's Christian minorities but on a much greater scale.[75] With the Macedonian Question's conclusion, attention was now given to Anatolia and the Armenian Question. Not wanting Anatolia to turn into another Macedonia, the CUP came up with the Türk Yurdu idea: that Anatolia would become the homeland of the Turks through policies of homogeneity in order to save both "Turkdom" and the empire. The CUP would engage in an "... increasingly radicalized demographic engineering program aimed at the ethnoreligious homogenization of Anatolia from 1913 till the end of World War I".[76] To that end, before Union and Progress's exterminatory anti-Armenian policies, anti-Greek policies were in order. Mahmut Celâl Bey, who would be appointed local secretary of the Union and Progress Party branch of Smyrna (modern İzmir), as well as Talât Pasha and Enver Pasha, would formulate a terror campaign against the Greek population in the Izmir vilayet with the aim of "cleansing" the area.[77][78] The purpose of the campaign was described in a CUP document:

The [Committee of] Union and Progress made a clear decision. The source of the trouble in western Anatolia would be removed, the Greeks would be cleared out by means of political and economic measures. Before anything else, it would be necessary to weaken and break the economically powerful Greeks.[79]

The campaign did not proceed with the same level of brutality as did the Armenian genocide during 1915 as the Unionists were afraid of a hostile foreign reaction, but during the "cleansing" operations in the spring of 1914 carried out by the CUP's Special Organisation it is estimated to have caused at the deaths of at least 300,000 Greeks with thousands more terrified Greeks fleeing across the Aegean to Greece.[80] In July 1914, the "cleansing operation" was stopped following protests from the ambassadors to the Porte with the French ambassador Maurice Bompard speaking especially strongly in defence of the Greeks, as well as the threat of war from Greece.[81] In many ways, the operation against Ottoman Greeks in 1914 was a trial run for the operations that were launched against Armenians in 1915.[81]

Cementing ties with Germany

Tensions in Europe rapidly increased as the events of the July Crisis unfolded. The CUP saw the July Crisis as the perfect chance to revise the outcome of the loss of Rumelia in the Balkan wars and the loss of the six vilayets in the Berlin Treaty through an alliance with a European power. With the fall of the Anglophile Kâmil Pasha and the Liberal Union, Germany took advantage of the situation by reestablishing its friendship with the Ottoman Empire that dated back to the Hamidian Era.[82]

Starting in 1897 Germany had a policy of Weltpolitik (World Politics), in which the Reich sought to become the world's dominant power. As part of its programme of Weltpolitik, Germany had courted the Ottoman Empire through a policy of providing generous loans to the Ottoman state (which had gone bankrupt in 1881, and which had trouble getting loans as a result), weapons and German officers to train the Ottoman army. The price of these loans, weapons and the German military mission to train the army was that the Ottoman state had to favour German corporations when awarding railway concessions and other public works, thus pushing the empire further into the German political and economic sphere of influence. An official German-Ottoman alliance was not signed until 1914, but from 1898 onwards, there was an unofficial German-Ottoman alliance. In 1898, the German emperor had visited the empire, in course of which Wilhelm II had proclaimed himself the "protector of Islam" before a cheering crowd. A large part of the reason for the German interest in the Ottomans was the belief by decision-makers in Berlin that the sultan-caliph could mobilise all of the world's Muslims to Germany's cause. Beyond that, having the Ottoman Empire as an ally would mean that in the event of a war, Russian and especially British forces that otherwise would be deployed against Germany would be sent to fight the Ottomans instead.[83]

Freiherr von Wangenheim, on behalf of the German government, secretly purchased Ikdam, the empire's largest newspaper, which under the new ownership began to loudly abuse Britain, France and Russia as Islam's greatest enemies while reminding its readers that the German emperor was the self-proclaimed "protector" of Islam.[84] Increasing large numbers of Germans, both civilians and soldiers began to arrive in Constantinople, who as the American ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Sr. reported filled all the cafes and marched through the streets "in the small hours of the morning, howling and singing German patriotic songs" while German officers were "rushing through the streets every day in huge automobiles".[85] On August 1, 1914, the Empire ordered a partial mobilization. Two days later it would order a general mobilization.[86] On 2 August, the Ottoman and German governments signed a secret alliance. The purpose of this alliance was to bring the Empire into World War I. On August 19th, a secret alliance with Bulgaria negotiated by Talât Pasha and Halil Bey and Bulgarian Prime Minister Vasil Radoslavov would also be signed.

On August 2nd Wangenheim informed the Ottoman cabinet that the German Mediterranean squadron under Admiral Wilhelm Souchon was steaming towards Constantinople, known as the famous pursuit of the Goeben and Breslau, and requested that the Ottomans grant the squadron sanctuary once it arrived (which the government gladly obliged to).[87] On August 16, a phony deal was signed with the Ottoman government supposedly buying the Goeben and Breslau for US$86 million, but with the German officers and crews remaining aboard.[88] In September, irregular warfare against Russia on the Cacausian border commenced; the ARF was asked to collaberate in these operations but refused.[89] Only in late September in response to cross-border raids would Russian Foreign Minister Sazonov allow the arming of Ottoman Armenian irregular volunteer regiments. On 24 September 1914, Admiral Souchon was appointed commander of the Ottoman navy.[90] Three days later, the Ottoman government in defiance of the 1841 treaty regulating the use of the Turkish straits linking the Black Sea to the Mediterranean closed the Turkish straits to international shipping, which was an immense blow to the Russian economy.[91]

On 21 October, Enver Pasha informed the Germans that his plans for the war were now complete and he was already moving his troops towards eastern Anatolia to invade the Russian Caucasus and to Palestine to attack the British in Egypt.[90] To provide a pretext for the war, Enver and Cemal Pasha (at this point minister of the navy) ordered Admiral Souchon to attack the Russian Black Sea ports with the German warships SMS Goeben and SMS Breslau and Ottoman gunboats in the expectation that Russia would declare war in response, which was carried out on the 29th.[92] After the act of aggression against his country Sazonov submitted an ultimatum to the Sublime Porte demanding that the Ottomans intern all of the German military and naval officers in their service; after its rejection Russia declared war on 2 November 1914.[92] The triumvirate called a special session of the Central Committee to explain that the time for the empire to enter the war had now come, and defined the war aim as: "the destruction of our Muscovite enemy [Russia] in order to obtain thereby a natural frontier to our empire, which should include and unite all the branches of our race".[92] This meeting prompted the minister of finance Mehmed Cavit Bey to resign and greatly infuriated the Grand Vizier Sait Halim Pasha.[93] On 5 November, Britain and France declared war on the Empire. On 11 November 1914, Mehmed V, in his capacity as Caliph of all Muslims, issued a declaration of jihad against Russia, Britain and France, ordering all Muslims everywhere in the world to fight for the destruction of those nations.[92]

With the expectation this new war would free the Empire of its constraints in sovereignty by the great powers, Talât Pasha as Minister of the Interior went ahead with accomplishing major goals of the CUP: unilaterally abolishing the centuries old Capitulations, prohibiting foreign postal services, terminating Lebanon's autonomy, and suspending the reform package for the Eastern Anatolian provinces that was in effect for just seven months. This unilateral action prompted a joyous rally in Sultanahmet Square.[94]

World War I and Genocidal Policies

Although the CUP had worked with the ARF during the Second Constitutional Era, factions in the CUP began to view Armenians as a fifth column that would betray the Ottoman cause after World War I with nearby Russia broke out;[95] these factions gained more power after the 1913 coup d'état. After the Ottoman Empire entered the war, most Ottoman Armenians sought to proclaim their loyalty to the empire with prayers being said in Armenian churches for a swift Ottoman victory; only a minority worked for a Russian victory.[96] The war began badly for the Ottomans on 6 November 1914 when British troops seized Basra and began to advance up the Tigris river.[97] Allied attempts to force the Bosphorus in a naval breakthrough failed, and an unsuccessful naval invasion followed in Gallipoli.

After the failure of the Sarikamish Expedition, the Three Pashas were involved in ordering the deportations and massacres of between 800,000 and 1.5 million Armenians in 1915–1916, known to history as the Armenian Genocide. The government would have liked to resume the "cleansing operations" against the Greek minority in western Anatolia, but this was vetoed under German pressure which was the Empire's only source of military equipment, as Germany wished for a neutral Greece in the war.

In December 1914, Cemal Pasha, encouraged by his anti-Semitic subordinate Baha el-Din, ordered the deportation of all the Jews living in the southern part of Ottoman Syria known as the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem (roughly what is now Israel) under the supposed grounds that most of the Jews came from the Russian Empire, but in reality because the CUP feared the Zionist movement as a threat to the Ottoman state.[98] The deportation order was vetoed by Wangenheim; Germany's leaders believed that the Jews had vast secret powers, and if the Reich were to assist the Jews in the war, the Jews in their turn would assist the Reich.[99] The Jews in the Yishuv were not deported, but the Ottoman authorities harassed the Jews in various other ways.[99]

In late 1914, Enver Pasha ordered that all Armenians serving in the Ottoman Army be disarmed and sent to labour battalions.[100] In early 1915, Enver ordered that all 200,000 Ottoman Armenian soldiers, now disarmed in the labour battalions be killed.[100]

The Special Organisation played a key role in the Armenian genocide. The Special Organisation, which was made of especially fanatical Unionist cadres, was expanded from August 1914 onwards.[101] Minister of the Interior Talât Pasha gave orders that all of the prisoners convicted of the worse crimes such as murder, rape, robbery, etc. could have their freedom if they agreed to join the Special Organisation to kill Armenians and loot their property.[102] Besides the hardened career criminals who joined in large numbers to have their freedom, the rank and file of Special Organisation killing units included Kurdish tribesmen attracted by the prospect of plunder and refugees from Rumelia, who were thirsting for the prospect of revenge against Christians after having been forced to flee from the Balkans in 1912.[103] The recruitment of thuggish career criminals straight from the prison system into the Special Organisation explains the very high incidence of rape during the Armenian genocide.

.png.webp)

On 24 May 1915, after learning of the "Great Crime", the British, French and Russian governments issued a joint statement accusing the Ottoman government of "crimes against humanity", the first time in history that this term had been used.[104] The British, French and Russians further promised that once the war was won they would put the Ottoman leaders responsible for the Armenian genocide on trial for crimes against humanity.[104] However, with the Anglo-Australian-New Zealand-Indian-French forces stalemated in Gallipoli and another Anglo-Indian expedition slowly advancing on Baghdad, the CUP's leaders were not threatened by the Allied threat to bring them to trial.[105] On 22–23 November 1915, General Sir Charles Townshend was defeated in the Battle of Ctesiphon by Nureddin Pasha and Goltz, thus ending the British advance on Baghdad.[97] On 3 December 1915, what was left of Townshend's force was besieged in Kut al-Amara. In January 1916, Gallipoli ended in an Ottoman victory with the withdrawal of the Allied forces; this victory did much to boost the prestige of the CUP regime.[97] After Gallipoli, Enver proudly announced in a speech that the empire had been saved while the mighty British empire had just been humiliated in an unprecedented defeat. On 28 April 1916, another Ottoman victory occurred at Kut with the surrender of Townshend's starving, disease-ridden troops to General Halil Kut.[106] The Anglo-Indian troops at Kut-already in broken health-were forced on a brutal march to POW camps in Anatolia, where most of them died.[106]

In 1916 Yakub Cemil would be arrested for plotting a coup against the regime that would have settled peace treaty with the Allied powers. Talât Pasha had him executed against Enver's will.[107]

In March 1917, Cemal Pasha ordered the deportation of the Jews of Jaffa, and after the discovery of the NILI spy network headed by the agronomist Aaron Aaronsohn who spied for the British out of the fear that Unionists would inflict the same fate on Jews as they did upon Armenians, ordered the deportation of all the Jews.[108] However, the British victories over the Ottomans in the autumn of 1917 with Field Marshal Allenby taking Jerusalem on 9 December 1917 saved the Jews of Palestine from being deported.[109]

Purges and Disbandment

As the military position of the Central Powers disintegrated, in 8 October 1918 Talât Pasha and the Unionist government resigned. On October 30 Marshal Ahmet Izzet Pasha, as the new Grand Vizier, negotiated the Armistice of Mudros at the end of the month. The position of the CUP was now untenable, and its top leaders fled on a secret voyage to Odessa and scattered from there.

During the party's last congress held on 1–5 November 1918, the remaining party members decided to abolish the party, which was severely criticized by the public because of the Empire's defeat. However just a week later the Renewel Party would be created, with Unionist assets and infrastructure being transferred over to the new party. It would be abolished by the Ottoman government in May 1919.

A purge was conducted by the Allied Powers. British forces occupied various points throughout the Empire, and through their High Commissioner Somerset Calthorpe, demanded that those members of the leadership who had not fled be put on trial, a policy also demanded by Part VII of the Treaty of Sèvres formally ending hostilities between the Allies and the Empire. The British carried off 60 Turks thought to be responsible for atrocities to Malta, where trials were planned. The new government, lead by a rehabilitated Liberal Union under Damat Ferid Pasha's premiership, obligingly arrested over 100 Unionist party and military officials by April 1919 and began a series of trials. These were initially promising, with one district governor, Mehmed Kemal [tr], being hanged on April 10.

Any possibility of a general effort at truth, reconciliation, or democratisation was lost when Greece, which had sought to remain neutral through most of World War I, was invited by France, Britain, and the United States to occupy western Anatolia in May 1919. Turkish nationalist leader Mustafa Kemal Pasha would rally the Turkish people to resist. Two additional organisers of the genocide were hanged, but while a few others were convicted, none completed their prison terms. The CUP and other Turkish prisoners held on Malta were eventually traded for almost 30 British prisoners held by Kemalist forces, obliging the British to give up their plans for international trials.

Much of the Unionist leadership was assassinated between 1920 and 1922 in Operation Nemesis. Dashnak sent out assassins to hunt down and kill the Unionists responsible for the Armenian genocide. Talât Pasha, as Minister of the Interior and later Grand Vizier and Foreign Minister as well as a member of the ruling triumvirate, was gunned down in Berlin by a Dashnak on 15 March 1921. Sait Halim Pasha, the Grand Vizier who signed the deportation orders in 1915 was killed in Rome on 5 December 1921. Dr. Bahattin Shakir, the commander of the Special Organisation was killed in Berlin on 17 April 1922 by a Dashnak gunman. Another member of the ruling triumvirate, Cemal Pasha was killed on 21 July 1922 in Tbilisi by Dashnaks. The final member of the Three Pashas, Enver Pasha was killed while fighting against the Red Army in Central Asia before Dashnak could assassinate him.

Most Unionists chose to rally around Mustafa Kemal and his Turkish national movement, however a rogue Unionist faction briefly revived the CUP in January 1922 which wished to revive the old CUP regime. However Unionist journalist Hüseyin Cahit declared the CUP would not contest the 1923 general election for the Ankara based parliament against Atatürk's Association for the Defence of Rights of Anatolia and Rumelia (soon to be the Republican People's Party). The last purge against the CUP occurred after a plot to assassinate Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Izmir by this rogue Unionist faction was uncovered in 1926, resulting in many surviving Unionists being executed in the Independence Tribunals, including Mehmed Cavit and Dr. Nazım.

Ideology

Hans-Lukas Kieser, Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide[110]

Turkish Nationalism

Though the Central Committee of the CUP was made up of intense Turkish nationalists, until the defeat in the First Balkan war in 1912–13, the CUP did not stress its Turkish nationalism in public as it would offend the non-Turkish population of the empire.[111] A further problem for Union and Progress was that the majority of the ethnic Turks of the empire did not see themselves as Turks at all, but rather simply as Sunni Muslims who happened to speak Turkish.[111] The Turkish historian Taner Akçam wrote that at the time of the First World War that "It is even questionable whether the broad mass of Muslims in Anatolia at the time understood themselves as Turks, or Kurds, rather than as Muslims".[112] Though the CUP was dedicated to a revolutionary transformation of Ottoman society by its "science-conscious cadres", the CUP were conservative revolutionaries who wished to retain the monarchy and Islam's status as the state religion as the Young Turks believed that the sultanate and Islam were an essential part of the glue holding the Ottoman Empire together.[113]

Cult of Science

The Unionists believed that the secret behind the success of the west was science, and that the more scientifically advanced a nation was, the more powerful it was.[114] According to the Turkish historian Handan Nezir Akmeșe, the essence of Union and Progress was the "cult of science" and a strong sense of Turkish nationalism.[115] Strongly influenced by French intellectuals such as Auguste Comte and Gustave Le Bon, the Unionists had embraced the idea of rule by a scientific elite.[116] For the Young Turks, the basic problem of the Ottoman Empire was its backward, impoverished status (today, the Ottoman Empire would be considered a third world country) and the fact that most of its Muslim population were illiterate; thus, most Ottoman Muslims could not learn about modern science even if they had wanted to.[117] The CUP had an obsession with science, above all the natural sciences (CUP journals devoted much text to chemistry lessons), and the Unionists often described themselves as "societal doctors" who would apply modern scientific ideas and methods to solve all social problems.[118] The CUP saw themselves as a scientific elite, whose superior knowledge would save the empire; one Unionist later recalled the atmosphere as: "Being a Unionist was almost a type of God-given privilege".[118]

Social Darwinism

Alongside the unbounded faith in science, the CUP embraced Social Darwinism and the völkisch, scientific racism that was so popular at German universities in the first half of the 20th century.[119] In the words of the sociologist Ziya Gökalp, the CUP's chief thinker, the German racial approach to defining a nation was the "one that happened to more closely match the condition of ‘Turkishness’, which was struggling to constitute its own historical and national identity".[120] The French racist Arthur de Gobineau whose theories had such a profound impact upon the German völkisch thinkers in the 19th century was also a major influence upon the CUP.[120] The Turkish historian Taner Akçam wrote that the CUP were quite flexible about mixing pan-Islamic, pan-Turkic, and Ottomanist ideas as it suited their purposes, and the Unionists at various times would emphasise one at the expense of the others depending upon the exigencies of the situation.[120] All that mattered in the end to the CUP was that the Ottoman Empire become great again, and that the Turks be the dominant group within the empire.[121]

The Young Turks had embraced Social Darwinism and pseudo-scientific biological racism as the basis of their philosophy with history being seen as a merciless racial struggle with only the strongest "races" surviving.[114] For the CUP, the Japanese government had ensured that the "Japanese race" were strongest in east Asia, and it was their duty to ensure that the "Turkish race" become the strongest in the near east.[114] For the CUP, just as it was right and natural for the superior "Japanese race" to dominate "inferior races" like the Koreans and the Chinese, likewise it would be natural for the superior "Turkish race" to dominate "inferior races" like Greeks and Armenians. This Social Darwinist perspective explains how the Unionists were so ferocious in their criticism of western imperialism (especially if directed against the Ottoman Empire) while being so supportive of Japanese imperialism in Korea and China. When Japan annexed Korea in 1910, the Young Turks supported this move under the Social Darwinist grounds that the Koreans were a weak people who deserved to be taken over by the stronger Japanese both for their own good and the good of the Japanese empire.[122] Along the same lines, the Social Darwinism of the Unionists led them to see the Armenians and the Greek minorities, who tended to be much better educated, literate and wealthier than the Turks and who dominated the business life of the empire as a threat to their plans for a glorious future for the "Turkish race".[123]

Islamism

During the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II, Pan-Islamism had become a hugely important part of the state ideology as Abdulhamid had often stressed his claim to be the caliph. The claim that Abdulhamid was the caliph, making him the political and spiritual leader of all Muslims not only caught on within the Ottoman Empire, but throughout the entire Dar-al-Islam (the "House of Islam", i.e. the Islamic world), especially in British controlled India. Despite deposing Abdulhamid in 1909, the CUP continued his pan-Islamic policies. For the CUP, keeping the sultanate-caliphate in being had the effect of not only reinforcing the loyalty of Ottoman Muslims to the empire, but was also a useful foreign policy tool. The fact that Indian Muslims seemed to have far more enthusiasm for the Ottoman sultan-caliph than they did for the British king-emperor was a matter of considerable concern for British decision-makers. The fear that the sultan-caliph might declare jihad against the British, and thereby plunge India into a revolt by its Muslims was a constant factor in British policy towards the Ottoman Empire.

Secularism

Democracy

In the words of the Turkish historian Handan Nezir Akmeșe, the commitment of the Unionists to the 1876 constitution that they professed to be fighting for was only "skin deep", and was more of a rallying cry for popular support than anything else.[124]

Anti-communism

Legacy

Turkey

As the defeat loomed in 1918, the CUP founded an underground group known as the Karakol organisation, and set up secret arms depots to wage guerrilla war against the Allies when they reached Anatolia.[125] The Karakol constituted an important faction within the post-war Turkish National Movement.[125] After its dissolving itself in 1918, many former Unionists were actively engaged in the Turkish national movement that emerged in 1919, usually from their work within the Karakol group.[126]

Besides Karakol, most leaders of the Turkish National Movement as well as the early Turkish Republic's intelligentsia were former Unionists. Besides future presidents of the Republic of Turkey Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, İsmet İnönü, and Celâl Bayar, other important Republican Turkish figures formerly associated with the CUP included Ziya Gökalp, Rauf Orbay, Fethi Okyar, Kâzım Karabekir, Adnan Adıvar, Şükrü Kaya, Rahmi Arslan, Çerkez Ethem, Bekir Sami, Yusuf Kemal, Celaleddin Arif, Ağaoğlu Ahmet, Recep Peker, Şemsettin Günaltay, Hüseyin Avni, Mehmet Emin Yurdakul, Mehmet Akif Ersoy, Celal Nuri İleri, Yunus Nadi Abalıoğlu, and Falih Rıfkı Atay. Union and Progress also has at times been identified with the two opposition parties that Atatürk attempted to introduce into Turkish politics against his own party (Republican People's Party) in order to help jump-start multiparty democracy in Turkey, namely the Progressive Republican Party and the Liberal Republican Party. While neither of these parties was primarily made up of persons indicted for genocidal activities, they were eventually taken over (or at least exploited) by persons who wished to restore the Ottoman caliphate. Consequently, both parties were required to be outlawed, although Kazim Karabekir, founder of the PRP, was eventually rehabilitated after the death of Atatürk and even served as speaker of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey.

It was also Karabekir who crystallised the modern Turkish position on the Armenian Genocide, telling Soviet peace commissioners that the return of any Armenians to territory controlled by Turks was out of the question, as the Armenians had perished in a rebellion of their own making. Historian Taner Akçam has identified four definitions of Turkey which have been handed down by the first Republican generation to modern Turks, of which the second is "Turkey is a society without ethnic minorities or cultures."[127] While the postwar reconstruction of eastern Europe was generally dominated by Wilsonian ideas of national self-determination, Turkey probably came closer than most of the new countries to ethnic homogeneity due to the subsequent population exchanges with neighbouring countries (e.g. population exchange between Greece and Turkey).

Atatürk was particularly eager that Islamism be marginalised, leading to the tradition of secularism in Turkey. This idea was culminated by the CUP in its more liberal heyday, as it was one of the first mass movements in Turkish history that abandoned political Islam.

Muslim World

The Young Turk Revolution and CUP's work had a great impact on Muslims in other countries. The Persian community in Istanbul founded the Iranian Union and Progress Party. Indian Muslims imitated the CUP oath administered to recruits of the organisation.

Elections

See also

References

Citations

- "Turkey in the First World War"

- "Committee of Union and Progress".

- "Committee For Union And Progress".

- Zurcher, Eric Jan (1997)

- The Unionist Factor: The Role of the Committee of Union and Progress in the Turkish National Movement 1905-1926.

- Kieser 2018, p. 43.

- İpekçi, Vahit (2006), Dr. Nâzım Bey'in Siyasal Yaşamı (in Turkish), İstanbul: Yeditepe Üniversitesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Enstitüsü.

- Bayat, Ali Haydar (1998), Hüseyinzade Ali Bey (in Turkish).

- Dergiler (PDF) (in Turkish), Ankara University.

- Shaw 1975, p. 257.

- Akçam 2007, p. 62.

- Kieser 2018, p. 46-49.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 50–51.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 53.

- Kieser 2018, p. 50.

- Shaw 1975, p. 265.

- Shaw 1975, p. 266.

- Akçam 2007, p. 58.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 57–58.

- Kieser 2018, p. 53-54.

- Akmeşe 2005, p. 57.

- Kieser 2018, p. 66.

- Kieser 2018, p. 65.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 87–88.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 96.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 89.

- Shaw 1975, p. 281.

- Kieser 2018, p. 75.

- Kieser 2018, p. 78.

- Kieser 2018, p. 62.

- Shaw 1975, p. 283.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 99.

- Akçam 2007, p. 94.

- Akçam 2007, p. 95–96.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 100.

- Shaw 1975, p. 290.

- Kieser 2018, p. 96-97.

- Kayalı, Hasan (1995), "Elections and the Electoral Process in the Ottoman Empire, 1876–1919" (PDF), International Journal of Middle East Studies, 27 (3): 265–86, doi:10.1017/s0020743800062085.

- Kieser 2018, p. 122.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 102.

- Kieser 2018, p. 119-120.

- Shaw 1975, p. 291.

- Kieser 2018, p. 124.

- Kieser 2018, p. 125.

- Kieser 2018, p. 99, 130.

- Kieser 2018, p. 134.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 135.

- Kieser 2018, p. 139.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 136.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 138.

- Shaw 1975, p. 296.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). Talaat Pasha: Father of Modern Turkey, Architect of Genocide. 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15762-7.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 140.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 159.

- Kieser 2018, p. 129, 132.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 140–41.

- Akmeşe 2005, p. 163.

- Akçam 2007, p. 118.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 163–64.

- Kieser 2018, p. 155.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 100.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 144–46.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, pp. 100-101.

- Karsh, Efraim (June 2001), "Review of The Rise of the Young Turks: Politics, the Military, and Ottoman Collapse by M. Naim Turfan", The International History Review, 23 (2): 440.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 155–56.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 161–62.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 164.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 166–67.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 168–69.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 169.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 169–70.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 165.

- Özbek, Nadi̇r (September 2007), "Defining the Public Sphere during the Late Ottoman Empire: War, Mass Mobilization and the Young Turk Regime (1908–18)", Middle Eastern Studies, 43 (5): 796–97, doi:10.1080/00263200701422709, S2CID 143536942.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 161.

- Kieser 2018, p. 167.

- Schull, Kent (December 2014), "Review of The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire by Taner Akçam", The Journal of Modern History, 86 (4): 975, doi:10.1086/678755.

- Kieser 2018, p. 174-176.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 103–4.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 102–3.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 103–6.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 105–6.

- Kieser 2018, p. 148.

- Mombauer, Annika (2001), Helmuth Von Moltke and the Origins of the First World War, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 120.

- Balakian 2004, p. 168.

- Balakian 2004, pp. 168–69.

- Kieser 2018, p. 188.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 114.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 115.

- Kieser 2018, p. 183, 190.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 116.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 132.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 117.

- Shaw 1975, p. 312.

- Kieser 2018, p. 191-192.

- Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2008), "Geographies of Nationalism and Violence: Rethinking Young Turk 'Social Engineering'", European Journal of Turkish Studies, 7.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 153.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 145.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, pp. 166-167.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 167.

- Libaridian, Gerard J (2000). "The Ultimate Repression: The Genocide of the Armenians, 1915-1917". In Walliman, Isidor; Dobkowski, Michael N (eds.). Genocide and the Modern Age. Syracuse, New York. pp. 203–236. ISBN 0-8156-2828-5.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 133–34.

- Akçam 2007, p. 135.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 134–35.

- Akçam 2007, p. 2.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, pp. 144-146.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, p. 147.

- Kieser 2018, p. 348.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, pp. 168-169.

- Karsh & Karsh 1999, pp. 169-170.

- Kieser 2018, p. 317.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 51–52.

- Akçam 2007, p. xxiv.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 59, 67–68.

- Worringer 2004, p. 216.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 34.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 35.

- Worringer 2014, pp. 193.

- Akçam 2007, p. 57.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 52–53.

- Akçam 2007, p. 53.

- Akçam 2007, pp. 53–54.

- Worringer 2014, p. 257.

- Akçam 2007, p. 150.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 40.

- Akmeșe 2005, p. 187.

- Akmeșe 2005, pp. 188–90.

- Balakian, Peter (2003). The Burning Tigris. New York. p. 375. ISBN 0-06-055870-9.

Bibliography

- Akçam, Taner (2007), A Shameful Act, London: Macmillan.

- Akın, Yiğit (2018). When the War Came Home: The Ottomans' Great War and the Devastation of an Empire. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503604902.

- Akmeșe, Handan Nezir (2005), The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to World War I, London: IB Tauris.

- Akşin, Sina (1987), Jön Türkler ve İttihat ve Terakki (in Turkish), İstanbul.

- Balakian, Peter (2004), The Burning Tigris, Harper Collins, p. 375, ISBN 978-0-06-055870-3.

- Campos, Michelle (2010). Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-80477678-3.

- Fromkin, David (1989), The Peace to End All Peace, New York: Henry Holt.

- Graber, CS (1996), Caravans to Oblivion: The Armenian Genocide, 1915, New York: Wiley.