Pontic Greeks

The Pontic Greeks (Greek: Πόντιοι, romanized: Pódii or Ελληνοπόντιοι, romanized: Ellinopódii; Turkish: Pontus Rumları or Karadeniz Rumları, Georgian: პონტოელი ბერძნები, romanized: P’ont’oeli Berdznebi) are an ethnically Greek[3][4] group who traditionally lived in the region of Pontus, on the shores of the Black Sea and in the Pontic Mountains of northeastern Anatolia. Many later migrated to other parts of Eastern Anatolia, to the former Russian province of Kars Oblast in the Transcaucasus, and to Georgia in various waves between the Ottoman conquest of the Empire of Trebizond in 1461 and the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829. Those from southern Russia, Ukraine, and Crimea are often referred to as "Northern Pontic [Greeks]", in contrast to those from "South Pontus", which strictly speaking is Pontus proper. Those from Georgia, northeastern Anatolia, and the former Russian Caucasus are in contemporary Greek academic circles often referred to as "Eastern Pontic [Greeks]" or as Caucasian Greeks, but also include the Turkic-speaking Urums.

Έλληνες του Πόντου (Ρωμιοί) | |

|---|---|

One of the Pontic flags | |

| Total population | |

| c. 2,000,000[1] – 2,500,000[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Greece, Georgia, Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Armenia, Cyprus, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Germany, United States, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Australia, Canada, Syria, Romania, Bulgaria, Egypt | |

| Languages | |

| Predominantly Modern and Pontic Greek. Also the languages of their respective countries of residence (Those include Russian, Turkish, Georgian and Urum language) | |

| Religion | |

| Greek Orthodox Christianity, Russian Orthodox Christianity, Sunni Islam (Mostly in Turkey) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Cappadocians, Caucasian Greeks, Urums |

Pontic Greeks have Greek ancestry and speak the Pontic Greek dialect, a distinct form of the standard Greek language which, due to the remoteness of Pontus, has undergone linguistic evolution distinct from that of the rest of the Greek world. The Pontic Greeks had a continuous presence in the region of Pontus (modern-day northeastern Turkey), Georgia, and Eastern Anatolia from at least 700 BC until 1923.[5]

Population

Nowadays, due to extensive intermarriage (also with non-Pontic Greeks), the exact number of Greeks from the Pontus, or people with Greek ancestry still living there, is unknown. After 1988, Pontian Greeks in the Soviet Union started to migrate to Greece settling in and around Athens and Thessaloniki, and especially Macedonia. The largest communities of Pontian Greeks (or people of Pontian Greek descent) around the world are:[6]

Mythology

In Greek mythology the Black Sea region is the region where Jason and the Argonauts sailed to find the Golden Fleece. The Amazons, female warriors in Greek Mythology lived in Pontus and minority lived in Taurica, also known as Crimea which is also the minor unique settlement of Pontic Greeks. The warlike characteristics of Pontic Greeks had once said to have been derived of Amazons of Pontus.

History

Antiquity

The first recorded Greek colony, established on the northern shores of ancient Anatolia, was Sinope on the Black Sea, circa 800 BC. The settlers of Sinop were merchants from the Ionian Greek city state of Miletus. After the colonization of the shores of the Black Sea, known until then to the Greek world as Pontos Axeinos (Inhospitable Sea), the name changed to Pontos Euxeinos (Hospitable Sea). In time, as the numbers of Greeks settling in the region grew significantly, more colonies were established along the whole Black Sea coastline of what is now Turkey, Bulgaria, Georgia, Russia, Ukraine, and Romania.

The region of Trapezus (later called Trebizond, now Trabzon) was mentioned by Xenophon in his famous work Anabasis, describing how he and other 10,000 Greek mercenaries fought their way to the Euxine Sea after the failure of the rebellion of Cyrus the Younger whom they fought for, against his older brother Artaxerxes II of Persia. Xenophon mentions that when at the sight of sea they shouted "Thalatta! Thalatta!" – "The sea! The sea!", the local people understood them. They were Greeks too and, according to Xenophon, they had been there for over 300 years.[13] A whole range of trade flourished among the various Greek colonies, but also with the indigenous tribes who inhabited the Pontus inland. Soon Trebizond established a leading stature among the other colonies and the region nearby become the heart of the Pontian Greek culture and civilization. A notable inhabitant of the region was Philetaerus (c. 343 BC–263 BC) who was born to a Greek father[14] in the small town of Tieion which was situated on the Black Sea coast of the Pontus Euxinus, he founded the Attalid dynasty and the Anatolian city of Pergamon in the second century BC.[14]

This region was organized circa 281 BC as a kingdom by Mithridates I of Pontus, whose ancestry line dated back to Ariobarzanes I, a Persian ruler of the Greek town of Cius. The most prominent descendant of Mithridates I was Mithridates VI Eupator, who between 90 and 65 BC fought the Mithridatic Wars, three bitter wars against the Roman Republic, before eventually being defeated. Mithridates VI the Great, as he was left in memory, claiming to be the protector of the Greek world against the barbarian Romans, expanded his kingdom to Bithynia, Crimea and Propontis (in present-day Ukraine and Turkey) before his downfall after the Third Mithridatic War.

Nevertheless, the kingdom survived as a Roman vassal state, now named Bosporan Kingdom and based in Crimea, until the 4th century AD, when it succumbed to the Huns. The rest of the Pontus became part of the Roman Empire, while the mountainous interior (Chaldia) was fully incorporated into the Eastern Roman Empire during the 6th century.

Middle Ages

Pontus was the birthplace of the Komnenos dynasty, which ruled the Byzantine Empire from 1082 to 1185, a time in which the empire resurged to recover much of Anatolia from the Seljuk Turks. In the aftermath of the fall of Constantinople to the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Empire of Trebizond was established by Alexios I of Trebizond, a descendant of Alexios I Komnenos, the patriarch of the Komnenos dynasty. The Empire was ruled by this new branch of the Komenos dynasty which bore the name Megas Komnenos Axouch (or Axouchos or Afouxechos) as early rulers intermarried with the family of Axouch, a Byzantine noble house of Turkic origin which included famed politicians such as John Axouch

This empire lasted for more than 250 years until it eventually fell at the hands of Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire in 1461. However it took the Ottomans 18 more years to finally defeat the Greek resistance in Pontus. During this long period of resistance many Pontic Greeks nobles and aristocrats married foreign emperors and dynasties, most notably of Medieval Russia, Medieval Georgia, or the Safavid Persian dynasty, and to a lesser extent the Kara Koyunlu rulers, in order to gain their protection and aid against the Ottoman threat. Many of the landowning and lower-class families of Pontus "turned-Turk", adopting the Turkish language and Turkish Islam but often remaining crypto-Christian before reverting to their Greek Orthodoxy in the early 19th century.

In the 1600s and 1700s, as Turkish lords called derebeys gained more control of land along the Black Sea coast, many coastal Pontians moved to the Pontic Mountains. There, they established villages such as Santa.[16]

Between 1461 and the second Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29, Pontic Greeks from northeastern Anatolia migrated as refugees or economic migrants (especially miners and livestock breeders) into nearby Armenia or Georgia, where they came to form a nucleus of Pontic Greeks which increased in size with the addition of each wave of refugees and migrants until these eastern Pontic Greek communities of the South Caucasus region came to define themselves as Caucasian Greeks.

During the Ottoman period a number of Pontian Greeks converted to Islam and adopted the Turkish language. This could be willingly, for example so to avoid paying the higher rate of taxation imposed on Orthodox Christians or in order to make themselves more eligible for higher level government and regular military employment opportunities within the empire (at least in the later period following the abolition of the infamous Greek and Balkan Christian child levy or 'devshirme', on which the elite Janissary corps had in the early Ottoman period depended for its recruits). But conversion could also occur in response to pressures from central government and local Muslim militia (e.g.) following any one of the Russo-Turkish wars in which ethnic Greeks from the Ottoman Empire's northern border regions were known to have collaborated, fought alongside, and sometimes even led invading Russian forces, such as was the case in the Greek governed, semi-autonomous Romanian Principalities, Trebizond, and the area that was briefly to become part of the Russian Caucasus in the far northeast.

Modern

Large communities (around 25% of the population) of Christian Pontic Greeks[17] remained throughout the Pontus area (including Trabzon and Kars in northeastern Turkey/the Russian Caucasus) until the 1920s, and in parts of Georgia and Armenia until the 1990s, preserving their own customs and dialect of Greek. It's estimated 345,000 Pontic Greeks live in Turkey as of 2018, although many still are in hiding and afraid of exposing their identity and religion due to ethnic tension, there are also converted ethnic Pontic Greeks whom after several generations have additionally been Turkified and assimilated.

Prior, during the second half of the nineteenth century a large number of pro-Russian Pontic Greeks from the Pontic Alps and the province of Erzerum, resettled in the area around Kars (which together with southern Georgia already had a nucleus of Caucasian Greeks). The mountainous vilayet (province) of Kars was ceded to the Russian Empire following the Russo-Turkish war that culminated in the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano. They had declined the expedient of conversion to Islam, abandoned their lands, and sought refuge in territory now controlled by their Christian Orthodox "protector", which used Pontic Greeks, Georgians, and southern Russians, and even non-Orthodox Armenians, Germans, and Estonians to "Christianize" this recently conquered southern Caucasus region, which it then administered as the newly created Kars Oblast (Kars Province). On the eve of World War I, the Young Turk administration exerted a policy of assimilation and ethnic cleansing of the Orthodox Christians in the Empire, which affected Pontian Greeks, as well as Armenians, Assyrians and Maronites. In 1916 Trabzon itself fell to the forces of the Russian Empire, fomenting the idea of an independent Pontic state. As the Bolsheviks came to power with the October Revolution (7 November 1917), Russian forces withdrew from the region to take part in the Russian Civil War (1917–1923).

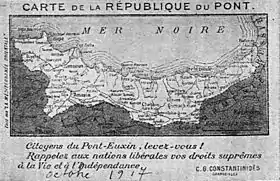

In 1917–1922, there existed an unrecognised state by the name Republic of Pontus, led by Chrysanthus, Metropolitan of Trebizond. In 1917 Greece and the Entente powers considered the creation of a Hellenic autonomous state in Pontus, most likely as part of a Ponto-Armenian Federation.[18] In 1919 on the fringes of the Paris Peace Conference Chrysanthos proposed the establishment of a fully independent Republic of Pontus, but neither Greece nor the other delegations supported it.[19]

While most Christian Pontians were forced to leave for Greece – avoiding nearby Russia, which in the decade post-1917 was plunged into the chaos of revolution and civil war – those who had converted to Islam (and in accordance with historical precedent were considered to have "turned Turk") remained in Turkey and were assimilated into the Muslim population of the north and northeast, where their bi-lingual Greek- and Turkish-speaking descendants can still be found.

Rumca, as the Pontian Greek language is known in Turkey, survives today, mostly among older speakers and crypto-Pontic Greeks in Turkey.[20] After the exchange most Pontian Greeks settled in Macedonia and Attica. Pontian Greeks inside the Soviet Union were predominantly settled in the regions bordering the Georgian SSR and Armenian SSR. They also had notable presence in Black Sea ports like Odessa and Sukhumi. About 100,000 Pontian Greeks, including 37,000 in the Caucasus area alone, were deported to Central Asia in 1949 during Stalin's post-war deportations. Big indigenous communities exist today in former USSR states, while through immigration large numbers can be found in Germany, Australia, and the United States.

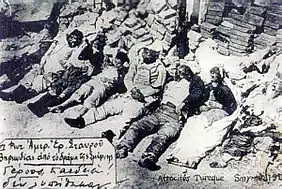

Genocide and population exchange

Like Armenians, Assyrians, and other Ottoman subjects, the Greeks of Trebizond and the short-lived Russian Caucasus province of Kars (which, in 1918, fell back under Ottoman control) suffered widespread massacres and what is now usually termed ethnic cleansing at the beginning of the 20th century, first by the Young Turks, and later by Kemalist forces. In both cases, the pretext was again that the Pontic Greeks and Armenians had collaborated or fought with the forces of their Russian co-religionists and "protectors" before the termination of hostilities between the two empires that followed the October Revolution. Death marches[21] through Turkey's mountainous terrain, forced labour in the infamous "Amele Taburu" in Anatolia, and slaughter by the irregular bands of Topal Osman resulted in tens of thousands of Pontic Greeks perishing during the period from 1915 to 1922. In 1923, after hundreds of years, those remaining were expelled from Turkey to Greece as part of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey defined by the Treaty of Lausanne. In his book Black Sea, author Neal Ascherson writes:

The Turkish guide-books on sale in the Taksim Meydane offer this account of the 1923 Katastrofĕ: 'After the proclamation of the Republic, the Greeks who lived in the region returned to their own country […].' Their own country? Returned? They had lived in the Pontos for nearly three thousand years. Their Pontian dialect was not understandable to twentieth-century Athenians.[22]

The suffering of the Pontian Greeks did not end upon their violent and forceful departure from the lands of their ancestors. Many Pontian Greek refugees perished during the voyage from Asia Minor to Greece. Notable accounts of these voyages have been included in Steve Papadopoulos' work on Pontian culture and history. Pontian Greek immigrants to the United States from that era were quoted as saying:

Many children and elderly died during the voyage to Greece. When the crew realized they were dead, they were thrown overboard. Soon the mothers of dead children started pretending that they were still alive. After witnessing what was done to the deceased, they would hold on to them and comfort them as if they were still alive. They did this to give them a proper burial in Greece.

According to the 1928 census of Greece, there were in total 240,695 Pontic Greek refugees in Greece : 11,435 from Russia, 47,091 from the Caucasus,[7] and 182,169 from the Pontus region of Anatolia.

In Turkey, however, together with Crypto-Armenians surfacing it has also given the Pontic community in Turkey more attention, estimates are up to 345,000[23][20] Pontic Greeks (Turkish: Pontus Rumları), presumably more, since ethnic minorities in Turkey have been through persecution.[24]

Remaining architecture and settlements

During their millennia-long presence on the Black Sea's southern coast, Pontic Greeks constructed a number of buildings, some of which still stand today. Many structures sit in ruins. Others, however, enjoy active use; one example is Nakip Mosque in Trabzon, originally built as a Greek Orthodox church during the 900s or 1000s.[25][26]

Ancient Greeks reached and settled the Black Sea by the 700s BCE; Sinope was perhaps the earliest colony.[27][28] According to the Pontic Greek historian Strabo, Greeks from the existing colony of Miletus settled the Pontus region.[27] Some walls from an early fortification stand in the modern Turkish city of Sinop (renamed from Sinope). These fortifications may date back to early Greek colonization in the 600s BCE.[29][30] During late Ottoman and recent Turkish times, the fortress housed a state prison.[31]

Between 281 BCE and 62 CE, the Mithridatic kings ruled the Pontos region and called it the Kingdom of Pontus.[32] While the ruling dynasty was Persian in origin, many kings had Greek ancestry, as Pontic rulers often married Seleucid nobility.[33] Some of these Persian/Greek rulers were interred in the Tombs of the kings of Pontus. Their necropolis is still visible in Amasya.[34][35]

One Pontic king, Pharnaces I of Pontus, may have built Giresun Castle in the 100s BCE.[36][37][38] There's also a chance it was built during medieval times.[39] From the castle, the Black Sea and much of Giresun are visible.

Many other structures date back to Greek occupation in ancient times. Ancient Greeks inhabited Giresun, then called Kerasous, from the 5th century BCE. During this time, they must also have used Giresun Island. The poet Apollonius of Rhodes mentioned this island in his best-known epic, the Argonautica. Altars on the island date to the Classical or Hellenistic period. Its use as a religious center continued after the rise of Christianity in the region. During Byzantine times, likely in the 400s or 500s, a monastic complex was built on the island, dedicated to either St Phocas of Sinope or Mary. It functioned both as a religious center and as a fortress.[40]

Many old Pontic Greek city-states remain in ruins. One is Athenae, an archaeological site near modern Pazar. It sat on the Black Sea coast and housed a temple to Athena.[41]

After Christianity spread to the Pontus region in Roman times, Pontic Greeks began constructing a number of churches, monasteries, and other religious buildings. The Virgin Mary Monastery in Şebinkarahisar District, Giresun Province may be one of the oldest Greek Orthodox monasteries in the region; Turkish archaeologists suspect it may date to the 2nd century. The monastery is made of carved stone and built into a cave. As of the mid-2010s, it's open for tourism.[42][43][44]

Other religious buildings were constructed later. Three ruined monasteries lie in Maçka, Trabzon Province: Panagias Soumela Monastery, Saint George Peristereotas Monastery, and Vazelon Monastery. These were built during early Byzantine times. Vazelon Monastery, for example, was built around 270 CE, and it retained great political and societal importance until its abandonment in 1922/3.[45][46] While St. George Monastery (also called Kuştul Monastery)[47] and Vazelon are abandoned, Sumela is a prominent tourist attraction.[48]

Pontic Greeks also constructed a number of non-religious buildings during Byzantine times. In the 500s, for example, a castle was built in Rize on the order of Justinian I. It was later expanded. The old fortress still stands today, serving tourists.[49]

Later, the Pontians built further churches and castles. Balatlar Church is a Byzantine church dating back to 660. It lies on the Black Sea coast. Despite vandalism and natural deterioration, the church still has old frescoes, which have been of interest to modern historians. The actual structure itself may date to Roman times. It likely had different uses over the centuries, potentially being a public bath and gymnasium before its use as a church. Pottery found at the site dates to the Roman and Hellenistic eras.[50][51] There is also speculation that a piece of the True Cross was found at Balatlar Church; however, it's more likely that the materials found were actually the relics of a saint or other holy person.[52]

Trabzon has at least three more late Byzantine churches that stand today. St. Anne Church, as the name suggests, was dedicated to Saint Anne, the mother of Mary. While the actual date of construction is uncertain, it was restored by the Byzantine emperors in 884 and 885.[53] It had three apses and a tympanum over the door. Unlike many churches in Trabzon, there is no evidence of it being converted into a mosque following Ottoman conquest in 1461.[54][55][56][57]

Two other structures in Trabzon, built as churches in Byzantine or Trapezuntine times, are now functional mosques. The New Friday Mosque, for example, was originally the Hagios Eugenios Church dedicated to Saint Eugenios of Trebizond.[55][58] Another is Fatih Mosque. It was originally the Panagia Chrysokephalos church, a cathedral in Trabzon.[59][60] The name is fitting; fatih means "conqueror" in both Ottoman and modern Turkish.[61]

Another church, Trabzon's Hagia Sophia, was perhaps built by Manuel I Komnenos.[62][63] It was used as a mosque after Turkish conquest; the frescoes may have been covered for Muslim worship. Hagia Sophia underwent restoration work in the mid-20th century.[64]

.jpg.webp)

After European invaders sacked Constantinople in 1204,[65] the Byzantine Empire fractured. The Pontus region went into the hands of the Komnenos family, who ruled the new Empire of Trebizond.

During the Empire of Trebizond, many new structures were built. One is Kiz Castle in Rize Province. The castle sits on an islet just off the Black Sea coast. According to Anthony Bryer, a British Byzantinist, it was built in the 1200s or 1300s on the order of Trapezuntine rulers.[66][67][68] Zilkale Castle is another fortress in Rize Province. According to the same historian, it may have been built by the Empire of Trebizond for local Hemshin rulers.[69] Yet another fortress, the Kov Castle in Gümüşhane Province, may have been built by Trapezuntine Emperor Alexios III.[70][71][72]

Alexios III, one of the last emperors under whom the Empire of Trebizond flourished, built Panagia Theoskepastos Monastery in the 1300s. It was an all-female monastery in Trabzon.[73][74] The monastery may undergo restoration work to boost tourism.[75]

After Mehmed the Conqueror lay siege to Trabzon in 1461, the Empire of Trebizond fell.[76] Many church buildings became mosques around this time, while others remained in the Greek Orthodox community.

Pontic Greeks continued to live and build under Ottoman rule. For example, Pontians in Gümüşhane established the valley town of Santa (today called Dumanlı) in the 1600s. Even today, many of the stone schools, houses, and churches built by Santa's Greek Orthodox residents still stand.[77][78]

They weren't divorced from Ottoman society, however; Pontic Greeks also contributed their labor to Ottoman construction projects. In 1610, Pontians built the Hacı Abdullah Wall in Giresun Province. The wall is 6.5 km (4.0 mi) long.[79]

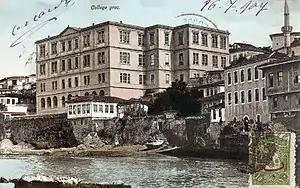

Trabzon remained an important center of Pontic Greek society and culture throughout Ottoman times. A scholar named Sevastos Kyminitis founded the Phrontisterion of Trapezous, a Greek school operating in Trabzon from the late 1600s to the early 1900s. It was an important center for Greek-language education across the whole Pontus region.[80][81] Some students came from outside of Trabzon to learn there (one example being Nikos Kapetanidis, who was born in Rize).

After the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856 guaranteed more religious freedom and civic equality for the Ottoman Empire's Jews and Christians,[82] new churches were constructed. One of these was the church at Cape Jason in Perşembe, Ordu Province. Local Georgians and Greeks built this church in the 1800s; it remains today.[83] Another was the small stone church in Çakrak, Giresun Province.[84] Still another was Taşbaşı Church in Ordu, built in the 1800s; after the Greek Orthodox were expelled from Turkey, it saw some use as a prison.[85][86] Many other less-notable churches remain throughout the Pontus region.[87][88][89]

Some of the old houses once belonging to Pontic Greeks still stand. For example, Konstantinos Theofylaktos, a wealthy Greek,[90] had a mansion built for him in Trabzon. It now functions as Trabzon Museum.[91][92]

Many structures have not survived to the present day. One example of this is Saint Gregory of Nyssa Church, Trabzon, which was dynamited in the 1930s to make way for a new building.[93]

Settlements

Some of the settlements historically inhabited by Pontian Greeks include (current official names in parenthesis):

- In Pontus proper

- Amasea, Samsunda (Amisos), Aphene, Argyrion (Akdağmadeni), Argyropolis (Gümüşhane), Athina (Pazar), Bafra, Comana Pontica (Gümenek), Etonia (Gümüşhacıköy), Fatsa, Galiana (Konaklar), Gemoura (Yomra), Hopa, Imera (Olucak), Kakatsis, Kelkit, Cerasus(Giresun), Kissa (Fındıklı), Kolonia (Şebinkarahisar), Nikopolis (Koyulhisar), Kotyora (Ordu), Kromni (Yağlıdere), Livera (Yazlık), Matsouka (Maçka), Meletios (Mesudiye), Myrsiphon (Merzifon), Mouzena (Aydınlar), Neocaesarea (Niksar), Ofis (Of), Oinoe (Ünye), Platana (Akçaabat), Rizounta (Rize), Santa (Dumanlı), Sinope (Sinop), Sourmena (Sürmene), Therme (Terme), i.e. the ancient of the Themiscyra, Evdokia (Tokat), Thoania (Tonya), Trebizond (Trabzon), Tripolis (Tirebolu), Cheriana (Şiran).

- Outside Pontus proper

- Adapazarı, Palea (Balya), Baiberdon (Bayburt), Efchaneia (Çorum), Sebastia (Sivas), Theodosiopolis (Erzurum), Erzincan (see below on Eastern Anatolia Greeks) and in the so-called Russian Asia Minor (see Batum Oblast, Kars Oblast' and Caucasian Greeks) and the so-called Russian Trans-Caucasus or Transcaucasia (see Černomore Guberniya, Kutais Guberniya, Tiflis Guberniya, Bathys Limni, Dioskourias (Sevastoupolis), Gonia, Phasis, Pytius and Tsalka).

- In Crimea and the northern Azov Sea

- Chersonesos, Kerkinitida, Panticapaeum, Soughdaia (Sudak), Tanais, Theodosia (Feodosiya).

- On the Taman peninsula and Krasnodar Krai, Stavropol Krai (in particular Essentuki)

- Germonassa, Gorgippa (Anapa), Heraclea Pontica, Phanagoria.

- On the southwestern coast of Ukraine and the Eastern Balkans

- Antiphilos, Apollonia (Sozopol), Germonakris, Mariupol, Mesembria (Nesebar), Nikonis, Odessos (Varna), Olbia, Tira.

Eastern Anatolia Greeks

Ethnic Greeks indigenous to the high plateau of Eastern Anatolia to the immediate south of the boundaries of the Empire of Trebizond – essentially the northern portion of the former Ottoman Vilayet of Erzurum between Erzinjan and Kars province, that is the western half of the Armenian Highlands – are sometimes differentiated from both Pontic Greeks proper and Caucasian Greeks.[94] These Greeks pre-date the refugees and migrants who left their homelands in the Pontic Alps and moved onto the Eastern Anatolian plateau after the fall of the Empire of Trebizond in 1461. They were mainly the descendants of Greek farmers, soldiers, state officials and traders, who settled in Erzurum province in the late Roman and Byzantine Empire period.

Unlike the thoroughly Hellenized areas of the western and central Black Sea coast and the Pontic Alps, the Erzinjan and Erzerum regions were primarily Turkish- and Armenian-speaking, with Greeks forming only a small minority of the population.[95] The Greeks of this region were consequently more exposed to Turkish and Armenian cultural influences than those of Pontus proper, and also more likely to have a strong command of the Turkish language, particular since the areas they inhabited had also been part of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum and other pre-Ottoman Turkish powers in Central and Eastern Anatolia.[96] Many are also known to have "turned Turk" in both the Seljuk and Ottoman periods, and consequently to have assimilated into Turkish society or reverted to Christian Orthodoxy in the 19th century. Erzurum province was invaded and occupied by the Russian Empire several times in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and large numbers of Eastern Anatolia Greeks are known to have collaborated with the Russians in these campaigns, particularly that of the 1828–29 Russo-Turkish War, alongside Pontic Greeks inhabiting areas to the immediate north of Erzinjan and Erzurum.

As with Pontic Greeks proper, those Eastern Anatolia Greeks who migrated eastwards into Kars province, Georgia, Armenia and Southern Russia between the early Ottoman period and 1829 generally assimilated into the branch of Pontic Greeks usually called Caucasian Greeks.[97] Those who remained and retained their Greek identity into the early 20th century were either deported to the Kingdom of Greece as part of the Exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey in 1923-4 or massacred in the Greek Genocide that occurred after the larger Armenian Genocide in the same part of Anatolia.[98]

Culture

The culture of Pontus has been strongly influenced by the topography of its different regions. In commercial cities like Trebizond, Samsunda, Kerasounda, and Sinopi upper-level education and arts flourished under the protection of a cosmopolitan middle class. In the inland cities such as Argyroupolis, the economy was based upon agriculture and mining, thus creating an economic and cultural gap between the developed urban ports and the rural centers which lay upon the valleys and plains extending from the base of the Pontic alps.

Language

Pontic's linguistic lineage stems from Ionic Greek via Koine and Byzantine Greek with many archaisms and contains loanwords from Turkish and to a lesser extent, Persian and various Caucasian languages.

Education

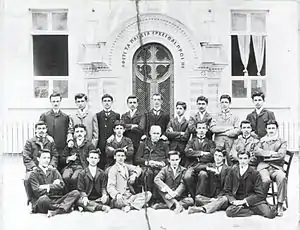

The rich cultural activity of Pontian Greeks is witnessed by the number of educational institutions, churches, and monasteries in the region. These include the Phrontisterion of Trapezous that operated from 1682/3 to 1921 and provided a major impetus for the rapid expansion of Greek education throughout the region.[99] The building of this institution still remains the most impressive Pontic Greek monument in the city.[100]

Another well known institution was the Argyroupolis, built in 1682 and 1722 respectively, 38 highschools in the Sinopi region, 39 highschools in the Kerasounda region, a plethora of churches and monasteries, most notable of which are the St. Eugenios and Hagia Sophia churches of Trapezeus, the monasteries of St. George and St. Ioannes Vazelonos, and arguably the most famous and highly regarded of all, the monastery of Panagia Soumela.

During the 19th century hundreds of schools were constructed by Pontic Greek communities in the Trebizond Vilayet, giving the region one of the highest literacy rates in the Ottoman Empire. The Greeks of Caykara, who according to Ottoman tax records converted to Islam during the 17th century, were also recognized for their educational facilities. Teachers from the Of-valley provided education for thousands of Anatolian Sunni and Sufi students in home schools and small madrassas. Some of these schools taught Pontic Greek alongside Arabic (and to a lesser extent Persian or Ottoman Turkish as well). Although Atatürk banned these madrassas during the early republican period, some of them remained functioning until the second half of the 20th century because of their remote location.[101][102] The effects of this educational heritage continue to this day, with many prominent religious figures, scientists and politicians coming from the areas influenced by the Naqshbandi Sufi orders of Pontic Greek extraction in Of, Caykara and Rize, among them president Erdogan, whose family originates from the village of Potamia.

Music

Pontian music retains elements of the musical traditions of Ancient Greece, Byzantium, and the Caucasus (especially from the region of Kars). Possibly there is an underlying influence from the native peoples who lived in the area before the Greeks as well, but this is not clearly established.

Musical styles, like language patterns and other cultural traits, were influenced by the topography of Pontos. The mountains and rivers of the area impeded communication between Pontian Greek communities and caused them to develop in different ways. Also significant in the shaping of Pontian music was the proximity of various non-Greek peoples on the fringes of the Pontic area. For this reason we see that musical style of the east Pontos has significant differences from that of the west or southwest Pontos. The Pontian music of Kars, for example, shows a clear influence from the music of the Caucasus and elements from other parts of Anatolia. The music and dances of Turks from Black Sea region are very similar to Greek Pontic and some songs and melodies are common. Except for certain laments and ballads, this music is played primarily to be danced to.

An important part of Pontic music is the Acritic songs, heroic or epic poetry set to music that emerged in the Byzantine Empire, probably in the 9th century. These songs celebrated the exploits of the Akritai, the frontier guards defending the eastern borders of the Byzantine Empire.

The most popular instrument in the Pontian musical collection is the kemenche or lyra, which is related closely with other bowed musical instruments of the medieval West, like the Kit violin and Rebec. Also important are other instruments such as the Angion or Tulum (a type of Bagpipe), the davul, a type of drum, the Shiliavrin, and the Kaval or Ghaval (a flute-like pipe).

The zurna existed in several versions which varied from region to region, with the style from Bafra sounding differently due to its bigger size. The Violin was very popular in the Bafra region and all throughout west Pontos. The Kemane, an instrument closely related to the one of Cappadocia, was highly popular in southwest Pontos and with the Pontian Greeks who lived in Cappadocia. Finally worth mentioning are the Defi (a type of tambourine), Outi and in the region of Kars, the clarinet.

Dance

Pontian dance retains aspects of Persian and Greek dance styles. The dances called Horoi/Choroi (Greek: Χοροί), singular Horos/Choros (Chorus) (Greek: Χορός), meaning literally "Dance" in both Ancient Pontian and Modern Greek languages, are circular in nature and each is characterized by distinct short steps. A unique aspect of Pontian dance is the tremoulo (Greek: Τρέμουλο), which is a fast shaking of the upper torso by a turning of the back on its axis. Like other Greek dances, they are danced in a line and the dancers form a circle. Pontian dances also resemble Persian and Middle Eastern dances because they are not led by a single dancer. The most renowned Pontian dances are Tik (dance), Serra, Maheria or Pyrecheios, Kotsari and Omal.

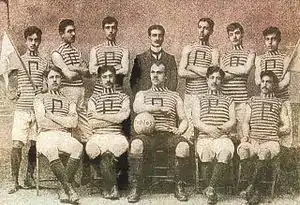

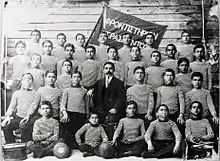

Sport

Pontic Greek history with organised sports began with extra-curricular activities offered by educational institutions. The students would establish athletics clubs providing the Pontic Greek youth with an opportunity to participate in organised sporting competition. The Hellenic Athletic Club, 'Pontos,' (Πόντος Μερζιφούντα) founded in 1903 was one such example formed by students attending Anatolia College in Merzifon Amasya. The college's forced closure in 1921 by the Turkish government resulted in the schools relocation to Greece in 1924, much of the Greek population would also follow suit in the aftermath of genocide population exchange. This resulted in the establishment of further Pontic and Anatolian Greek sporting clubs in Greece, most notably:

- Apollon Pontou FC

- PAOK FC

- AEK FC

- AE Pontion Verias

- AO Ellas Pontion

- AE Ponton Evmirou

- AE Ponton Vatalakkou

- AEP Kozanis

- Pontikos Neas Santas

Outside of Greece, due to the widespread Pontic Greek diaspora, association football clubs also exist. In Australia, the Pontian Eagles SC are a semi-professional team based in Adelaide, South Australia and in Munich, Germany, FC Pontos have an academy relationship with PAOK FC.

Military Tradition

On 19 May of each year, the Evzonoi of the Greek Army Presidential Guard ceremonial unit wear the traditional black Pontic uniform to commemorate the Pontic genocide.[103]

Cuisine

Pontic cuisine specialities include:

- Felia (φελία), dessert

- Kinteata (κιντέατα), nettle soup

- Otía (ωτία), dessert

- Pirozhki (πιροσκί)

- Pishía (πισία), Pontian pita

- Sousamópita (σουσαμόπιτα)

- Tanoménon sorvá or Tanofái (τανωμένον σορβά, τανοφάι), soup

- Tsirichtá (τσιριχτά), type of loukoumades

- Siron, pasta

- Varenika (βαρένικα), type of ravioli

- Sourva, wheat or barley porridge[104]

- Tan, type of buttermilk[104]

- Pilav, rice dish

- Dolmades, stuffed leaf dish

- Kibbeh made with lamb and/or beef

Pontic Greeks in popular culture

- In the 1984 movie Voyage to Cythera (Ταξίδι στα Κύθηρα),[105] directed by Theodoros Angelopoulos, the protagonist is a Pontian Greek who was deported to the Soviet Union after the Greek civil war. He returns to Greece after 32 years.

- In his 1998 movie From the Edge of the City (Από την άκρη της πόλης),[106] the film director Constantinos Giannaris describes the life of a young "Russian Pontian" from Kazakhstan in the prostitution underworld of Athens.

- In the 1999 movie Soil and Water (Χώμα και νερό),[107] one of the characters is a Pontian Greek from Georgia who works as a woman's trafficker for a strip club.

- In the 2000 memoir "Not Even My Name: From a Death March in Turkey to a New Home in America, A Young Girl's True Story of Genocide and Survival" by Thea Halo, life in the Pontus region is described by her mother Sano Halo before and after the Greek Genocide.

- In the 2000 movie The Very Poor, Inc. (Πάμπτωχοι Α.Ε.),[108] one of the characters is a Pontian Greek from the Soviet Union named Thymios Hloridis. A mathematician with a specialty in chaos theory, Hloridis is forced to make a living selling illegal cigars in front of the stock-market.

- In the 2003 Turkish movie Waiting for the Clouds (Bulutlari Beklerken, Περιμένοντας τα σύννεφα),[109] one Pontian Greek woman, who didn't leave as a child with her brother during the general expulsion of Pontian Greeks to the Greek Peloponnese after the first world war and the Treaty of Lausanne's mandated Population transfer, meets Thanasis, a Pontian Greek man from the Soviet Union, who helps her to find her brother in Greece. The movie makes some references to the pontian genocide.

- In the 2008 short movie Pontos,[110] written, produced, and directed by Peter Stefanidis, he aims to capture a small part of the genocide from the perspective of its two central characters, played by Lee Mason (Kemal) and Ross Black (Pantzo).

- In 2012 The Black Sea by Stephanos Papadopoulos a collection of poems depicting the imagined trials and voyages of the Pontic Greek exodus from the region was published by Sheep Meadow Press.

Notable Pontian Greeks

Ancient

Medieval

Modern

- Ioannis Amanatidis

- George Andreadis

- Peter Andrikidis

- Antonis Antoniadis

- Joannis Avramidis

- Konstantin Bazelyuk

- A.I. Bezzerides

- Georges Candilis

- Alexander Deligiannidis

- Lefter Küçükandonyadis

- Alex Dimitriades

- Odysseas Dimitriadis

- Ioannis Fetfatzidis

- Adonis Georgiadis

- Georgios Georgiadis

- Giorgos Georgiadis

- George Gurdjieff

- Nikos Kapetanidis

- Michael Katsidis

- Stelios Kazantzidis

- Yevhen Khacheridi

- Matthaios Kofidis

- Savvas Kofidis

- Venetia Kotta

- Arkhip Kuindzhi

- Filon Ktenidis

- Mike Lazaridis

- Angeliki Laiou

Video

- Documentary on the Pontic Greeks culture, dances and songs: ΤΟ ΑΛΑΤΙ ΤΗΣ ΓΗΣ – Ποντος HD on YouTube

- Documentary showcasing Pontic Greek music and dance tradition: ΤΟ ΑΛΑΤΙ ΤΗΣ ΓΗΣ – Ποντιακό γλέντι HD on YouTube

Gallery

A wealthy Pontic Greek family in Geneva

A wealthy Pontic Greek family in Geneva A middle-class Pontic Greek family

A middle-class Pontic Greek family Pontic Greek family in the courtyard of a Trapezounta house (modern Trabzon, Turkey)

Pontic Greek family in the courtyard of a Trapezounta house (modern Trabzon, Turkey) Pontian Greek ladies and children of Trapezounta

Pontian Greek ladies and children of Trapezounta Pontic Greek couple in Trapezounta

Pontic Greek couple in Trapezounta Pontian Greek athletics team from Kerasounta (modern Giresun, Turkey)

Pontian Greek athletics team from Kerasounta (modern Giresun, Turkey) Pontian Greek female students of Trapezounta

Pontian Greek female students of Trapezounta

Pontian Greek Canoe, off the coast of Trapezounta

Pontian Greek Canoe, off the coast of Trapezounta Pontic Greek from the Caucasus as member of the Russian Imperial Army

Pontic Greek from the Caucasus as member of the Russian Imperial Army Pontic Greek family from Magaracik, former Russian Caucasus province of Kars

Pontic Greek family from Magaracik, former Russian Caucasus province of Kars

See also

- Amaseia, a city with Pontic Greeks

- Cappadocian Greeks

- Caucasian Greeks

- Urums

- Laz people

- Greek genocide

- Greek Muslims

- Yannis Vasilis, a former ultra-nationalist Turk turned pacifist and promoter of Greek heritage after finding out his Pontic Greek heritage.

References

- Dufoix, Stephane (2008). Diasporas. University of California Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780520941298.

For example, there are 2 million Pontic Greeks worldwide, mostly in Russia, Ukraine, Greece, Germany, and Sweden.

- Phrankoulē-Argyrē, Ioustinē (2006). Spyridon, Archbishop of America, 1996 – 1999: the heritage. Hellēnika Grammata. p. 175.

Οι ξεριζωμένοι και διασκορπισμένοι στα πέρατα της οικουμένης έλληνες του Πόντου συμποσούνται σήμερα γύρω στα 2.500.000.

- Alan John Day; Roger East; Richard Thomas (2002). A Political and Economic Dictionary of Eastern Europe. Psychology Press. p. 454. ISBN 1857430638.

Pontic Greeks An ethnic Greek minority found in Georgia and originally concentrated in the breakaway republic of Abkhazia. The Pontic Greeks are ultimately descended from Greek colonists of the Caucasus region (who named the Black Sea the Pontic Sea)

- Totten, Samuel; Bartrop, Paul Robert; Jacobs, Steven L. (2008). Dictionary of Genocide: A-L. ABC-CLIO. p. 337. ISBN 978-0313346422.

Pontic Greeks, Genocide of. The Pontic (sometimes Pontian) Greek genocide is the term applied to the massacres and deportations perpetuated against ethnic Greeks living in the Ottoman Empire at the hands of the Young Turk government between 1914 and 1923. The name of this people derives from the Greek word pontus, meaning "sea coast," and refers to the Greek population that lived on the south-eastern coast of the Black Sea, that is, in northern Turkey, for three millennia.

-

Wood, Michael (2005). In Search of Myths & Heroes: Exploring Four Epic Legends of the World. University of California Press. p. 109. ISBN 0520247248.

THE PONTIC GREEKS In the valleys running down to the Black Sea shore around Trebizond, the Greek presence lasted from 700 BC until our own time. Only after the catastrophe of 1922, when the Greeks were expelled from Turkey, did most of them migrate to Greece, or into Georgia where many had started to go before the First World War when the first signs of burning were in the air. The Turks had entered central Anatolia (the Greek word for ‘the east’) in the eleventh century, and by 1400 it was entirely in their hands, though the jewel in the crown, Constantinople itself, wasn’t taken till 1453. By then the Greek-speaking Christian population was in a minority, and even their church services were conducted partly in Greek, partly in Turkish. In Pontus, on the Black Sea coast, it was a different story. Here the Greeks were a very strong presence right up into modern times. Although they had been conquered in 1486, they were still the majority in the seventeenth century and many converted to Islam still spoke Greek. Even in the late twentieth century the authorities in Trebizond had to use interpreters to work with the Muslim Pontic-Greek speakers in the law courts, as the language was still spoken as their mother tongue. This region had a thriving oral culture into the last century and a thriving oral culture into the last century and a whole genre of ballads comes down from the Ancient Greeks…

- Pontian Diaspora, 2000.

- Standard Languages and Language Standards: Greek, Past and Present, Alexandra Georgakopoulou, Michael Stephen Silk, page 52, 2009

- Greece: The Modern Sequel: from 1821 to the present. John S. Koliopoulos,Thanos Veremis,C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd (Mai 2007) P. 285

- Konstantinidis K., "Οι Έλληνες του Πόντου" (in English: The Greeks of Pontus), p.195

- Fotiadis K., "Οι Έλληνες της πρώην Σοβιετικής Ένωσης. Η γένεση της διασπορας" (in English: "The Greeks of the former Soviet Union. The origination of the Diaspora"), p.36

- (in Russian) Этнический Атлас Узбекистана / Ethnic Atlas of Uzbekistan Archived 7 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- 2011 Armenian Census

- Who are the Pontians?. Angelfire.com. Retrieved on 2011-02-12.

- Renée Dreyfus; Ellen Schraudolph (1996). Pergamon: The Telephos Frieze from the Great Altar. University of Texas Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-88401-091-0.

Philetairos of Tios on the Black Sea, son of a Greek father and a Paphlagonian mother, a high-ranking officer in the army of King Lysimachos and also his confidant, was the actual founder of Pergamon.

- Bunson, Matthew (2004). OSV's encyclopedia of Catholic history. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 1-59276-026-0.

BESSARION, JOHN (c. 1395–1472) + Greek scholar, cardinal, and statesman. One of the foremost figures in the rise of the intellectual Renaissance

- Bryer, Anthony (1975). "Greeks and Türkmens: The Pontic Exception". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 29: 122. doi:10.2307/1291371. JSTOR 1291371.

- Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact on Greece. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-85065-702-6.

- A Short History of Modern Greece, 1821–1940, Edward Seymour Forster, 1941, p. 66.

- Dimitri Kitsikis, Propagande et pressions en politique internationale, 1919–1920 (Paris, 1963) pp. 417–422.

- ""Crypto-Pontus Greeks, between Islam and Christianity." (In Turkish)". repairfuture.net. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Library Journal Review of Not Even My Name by Thea Halo.

- Ascherson, Neal (1996). Black Sea. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8090-1593-1.

- Project, Joshua. "Pontic Greek in Turkey". joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Crypto-Christianity in the Black sea". Ortodokslar Topluluğu(The Orthodox society) (in Turkish). 24 September 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Sinclair, T. A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume II. Pindar Press. p. 72. ISBN 9781904597759.

- Ballance, Selina (1960). "The Byzantine Churches of Trebizond". Anatolian Studies. 10: 152–153. doi:10.2307/3642433. JSTOR 3642433.

- Gorman, Vanessa B. (2001). Miletos, the Ornament of Ionia: A History of the City to 400 B.C.E. University of Michigan Press. pp. 63–66. ISBN 978-0-472-11199-2.

- Drews, Robert (1976). "The earliest Greek settlements on the Black Sea". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 96: 18–31. doi:10.2307/631221. JSTOR 631221.

- "Trading Posts and Fortifications on Genoese Trade Routes from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015.

- "Kaleler (Castles)". Sinop Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism (in Turkish). Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

- "Tarihi Sinop Kale Cezaevi - Tarihçe" (in Turkish). Sinop Culture and Tourism Directoriate. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- "Pontus". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Højte, Jakob Munk (22 June 2009). Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press. p. 64. ISBN 9788779344433.

- "Amasya Harşena Dağı Ve Pontus Kral Kaya Mezarları Unesco Dünya Miras Geçici Listesinde". General Directorate of Cultural Assets and Museums (in Turkish). Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

- "Mount Harşena and the Rrock-tombs of the Pontic Kings". United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Permanent Delegation of Turkey to UNESCO. 2015.

- "Giresun Castle". Black Sea-Silk Road Corridor.

- Alan, Hakan (2010). "Black Sea Region". Turkey (English). AS Books. p. 166. ISBN 9789750114779.

- Aydın, Mustafa (1 January 2012). "Giresun Kalesi (1764-1840)" [The Giresun Castle (1764-1840)]. Karadeniz İncelemeleri Dergisi. 2012: 39–56.

- Elçilik, Büyük (1989). Turkey Today: Issues 113-136. Turkish Embassy. p. 6.

- Ertekin M. Doksanaltı; İlker M. Mimiroğlu (2011). "Giresun/Aretias - Kalkeritis Island". THE PHENOMENA OF CULTURAL BORDERSAND BORDER CULTURES ACROSS THE PASSAGEOF TIME. Trnava University. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-80-8082-500-3.

- Smith, William (1857). "Volume 1". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London, UK.

ATHE'NAE (Atenah), a city and port of Pontus (Steph. B. s. v. Άθήναί), with an Hellenic temple.

- "Meryemana Manastırı". Şebinkarahisar Kaymakamlığı (in Turkish). Government of Şebinkarahisar, Giresun. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- Yetgin, Gültekin; Mutlu, Gülsen (23 July 2015). "Meryem Ana Manastırı'na Yunanlı ziyareti". Anadolu Agency (in Turkish). Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- "Meryemana Monastery (Ruins)". Giresun Provincial Culture and Tourism Directorate (in Turkish). Giresun Province. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Çavuş, Ahmet (January 2016). "A Lesser Known Important Cultural Heritage Source and Religious Tourism Value in Turkey: Vazelon (Zavulon) Monastery" (PDF). International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. Center for Promoting Ideas. 6 (1). ISSN 2220-8488.

- Demciuc, Vasile M.; Köse, İsmail (July 2014). "VAZELON (ST. JOHN) MONASTERY OF MAÇKA TREBIZOND". Codrul Cosminului. 20 (1). ISSN 1224-032X.

- Η Ιστορία της Μονής στον Πόντο Archived 2006-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, peristereota.com

- "Sümela Manastırı" (in Turkish).

- "Kaleler" (in Turkish). Rize İl Kültür ve Turizm Müdürlüğü. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- Alper, Eda Güngör (2014). "Hellenistic and Roman Period Ceramic Finds from the Balatlar Church Excavations in Sinop between 2010-2012". Anatolia Antiqua. 22: 35–49.

- Yuksel, Fethi Ahmet; Koroglu, Gulgun; Yildiz, Mehmet Safi (January 2012). "Archaeogeophysical Studies Conducted on Sinop Balatlar Church". Symposium on the Application of Geophysics to Engineering and Environmental Problems 2012: 610. doi:10.4133/1.4721889.

- Hafiz, Yasmine (3 August 2013). "Piece Of Jesus' Cross Found? Archaeologists Discover 'Holy Thing' In Balatlar Church In Turkey". Huffpost.

- Sagona, A. G. (2006). The Heritage of Eastern Turkey: from Earliest Settlements to Islam. Macmillan Art Publishing. p. 170. ISBN 9781876832056.

...the small Church of St. Anne, the oldest extant Byzantine building in Trabzon, rebuilt during the reign of Basil I (AD 867-86).

- Ćurčić, Slobodan; Krautheimer, Richard (1992). Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. Yale University Press. p. 395. ISBN 9780300052947.

- Turkey Today: Issues 113-136. Turkish Embassy. 1989. p. 7.

- Özmen, Can (October 2016). "Value Assessment on Hagia Sophia Complex in Trabzon" (PDF). Ankara, Turkey: Middle East Technical University. p. 88.

- Eastmond, Anthony (2017). Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium: Hagia Sophia and the Empire of Trebizond. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781351957229.

- Sinclair, T. A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume II. Pindar Press. p. 50. ISBN 9781904597759.

- Gabriel Millet, "Les monastères et les églises de Trébizonde", Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, 19 (1895), p. 423

- Selina Ballance, "The Byzantine Churches of Trebizond", Anatolian Studies, 10 (1960), p. 146

- Redhouse, James William (1856). An English and Turkish Dictionary. B. Quarich. p. 62.

- Eastmond, Anthony. "The Byzantine Empires in the Thirteenth Century" in Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium: Hagia Sophia and the Empire of Trebizond. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004, p. 1.

- Kalin, Arzu; Yilmaz, Demet (2012). "A Study on Visibility Analysis of Urban Landmarks: The Case of Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya) in Trabzon" (PDF). METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture. 29 (1): 241–271. doi:10.4305/metu.jfa.2012.1.14.

Though the actual date of founding is still obscure, according to some researchers the main church (probably the monastery) is believed to be founded by Manuel I the Great Comnenos (1238-1263) or his immediate successors.

- Some details of the preservation can be read in David Winfield, "Sancta Sophia, Trebizond: A Note on the Cleaning and Conservation Work", Studies in Conservation, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Nov., 1963), pp. 117-130.

- Cartwright, Mark. "1204: The Sack of Constantinople". Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- BRYER, A., & WINFIELD, D. (1985). The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos. Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.02923.

- "Kız Kalesi - Rize". Kültür Portalı (in Turkish). Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

- "Tarihi Kız Kalesi Restore Ediliyor". Haberler. Anadolu Agency. 2014. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020.

- Bryer, Anthony; Winfield, David (1985). Byzantine Monuments and Topography of the Pontos. Dumbarton Oaks Centre Studies. 2. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. p. 348. ISBN 978-1597403177.

- Macler, Frédéric; Gulbenkian, Fundação Calouste (1985). "Revue des études arméniennes" [Journal of Armenian Studies]. Revue des études arméniennes (in French and English). Association de la revue des études arméniennes: 214.

- "Kov Castle". Gumushane Culture and Nature.

- "Gümüşhane Kaleleri" (in Turkish). Governorship of Gümüşhane.

- Öztürk, Özhan (2007). "Trabzon imparatorlarının kemikleri belediye mezarlığına mı gömülecek?" (in Turkish). Radikal Newspaper. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011.

- Yücel, Erdem (1989). Trabzon and Sumela. Net Turistik yayınlar. p. 49. ISBN 9789754790566.

- "Kızlar Monastery to serve as museum, enliven cultural life". Daily Sabah. Anadolu Agency. 24 February 2020.

- Franz Babinger, "La date de la prise de Trébizonde par les Turcs (1461)", Revue des études byzantines, 7 (1949), pp. 205–207 doi:10.3406/rebyz.1949.1014

- Bryer, Anthony (1988). Peoples and Settlement in Anatolia and the Caucasus, 800-1900. Variorum Reprints. p. 234. ISBN 9780860782223.

New Greek settlements sprung up south of the Pontic Alps in the highland valleys of Torul (6), Zigana (3)...and Santa (4) especially

- "Works initiated for concrete structures in Santa ruins". Hurriyet Daily News. 6 July 2018.

- "Turizm". Governorship of Giresun Province.

- Özdalga, Elisabeth (2005). Late Ottoman society: the intellectual legacy. Routledge. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-415-34164-6.

- Salvanou, Emilia. "Φροντιστήριο Τραπεζούντας ("Phrontisterion of Trapezous")". Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Davison, Roderic H. (1954). "Turkish Attitudes Concerning Christian-Muslim Equality in the 19th Century". The American Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 59 (4): 844–864. doi:10.2307/1845120. JSTOR 1845120.

- William J. Hamilton, Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia;With Some Account of Their Antiquities and Geology v.1 (London: John Murray, 1842), 269

- "ÇAKRAK KİLİSESİ VE KÖPRÜSÜ". Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

- "Ordu ili tarihi yapılar kilise ve kaleler". Karalahana (in Turkish). 2007. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008.

- "Taşbaşı Church Map And Location".

- "Turkey Cultural Heritage Map". Hrant Dink Foundation. Hrant Dink Foundation.

- "Part 12: Gümüşhane". Karalahana. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012.

- "Gumushane". Karalahana. 2007. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012.

- Warner, Jayne L. (2017). Turkish Nomad: The Intellectual Journey of Talat S Halman. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 379. ISBN 9781838609818.

- Kostaki Mansion - Museum of Trebizond Archived 2011-10-11 at the Wayback Machine. Kara Lahana, retrieved 12 October 2011

- Bussmann, Michael; Tröger, Gabriele (2015). Türkei Reiseführer: Individuell reisen mit vielen praktischen Tipps (in German). Michael Müller Verlag. ISBN 9783956542978.

The museum is located in the magnificent mansion of the former Trapezuntine banker Kostaki Teophylaktos...

- Bryer, Anthony; Winfield, David; Ballance, Selina; Isaac, Jane (2002). The Post-Byzantine Monuments of the Pontos. Ashgate. p. 202. ISBN 9780860788645.

- Topalidis, Sam, 'A Pontic Greek History' (2006), introduction.

- Koromela, Marianna and Evert, Lisa,'Pontos-Anatolia : northern Asia Minor and the Anatolian plateau east of the upper Euphrates : images of a Journey', (1989), p. 37.

- Topalidis, Sam, 'A Pontic Greek History' (2006), pp. 39–46.

- Xanthopoulou-Kyriakou, Artemis, 'The Diaspora of the Greeks of the Pontos: Historical Background', Journal of Refugee Studies, 4, (1991), pp. 26–31.

- Topalidis, Sam, 'A Pontic Greek History' (2006), pp. 22–25.

- Özdalga, Elisabeth (2005). Late Ottoman society: the intellectual legacy. Routledge. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-415-34164-6.

- Bryer, Anthony; Winfield, David (2006). The post-Byzantine monuments of Pontos. Ashgate. p. xxxiii. ISBN 978-0-86078-864-5.

- A Nation of Empire – Ottoman Legacy Turkish Modernity Archived 17 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine Michael E. Meeker – University of California Press, 2001

- Trabzon Greek – A language without a Tongue Archived 11 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Ömer Asan on Karalahana.com

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJ6psL0DnBw

- Voutira, Eftihia (2011). The 'right to Return' and the Meaning of 'home'. Lit. p. 10. ISBN 9783643901071.

A few of my school friends were Pontic Greeks, and I remember their exotic foods, such as sourva and tan...

- Taxidi sta Kythira (1984), imdb.com

- Apo Tin Akri Tis Polis, imdb.com

- kai nero, imdb.com

- The Very Poor, Inc., imdb.com

- Waiting for the Clouds, imdb.com

- Pontos (2008), imdb.com

Bibliography

- Halo, Thea. Not Even My Name. Picador. 2000. ISBN 978-0-312-26211-2.

- Hofmann, Tessa, ed. Verfolgung, Vertreibung und Vernichtung der Christen im Osmanischen Reich 1912–1922. Münster: LIT, 2004. ISBN 978-3-8258-7823-8

- Berikashvili, Svetlana. Morphological aspects of Pontic Greek spoken in Georgia. LINCOM GmbH, 2017. ISBN 978-3-8628-8852-8

- Bruneau, Michel (2015). "Le patrimoine menacé des Grecs pontiques, entre Turquie et Grèce". Anatoli (in French) (6). doi:10.4000/anatoli.315.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pontic Greeks. |

.jpg.webp)