Seyfo

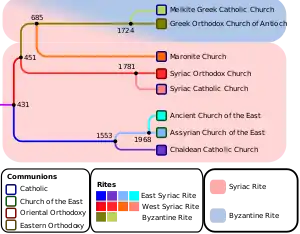

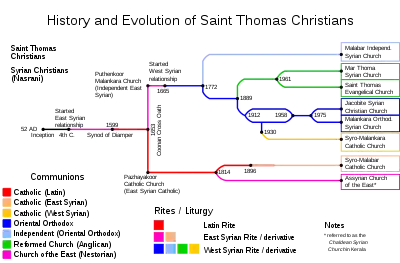

The Seyfo or Sayfo (Syriac: ܣܝܦܐ, literally meaning "sword";[4] see below), also known as the Assyrian Genocide,[5][6] the Aramean Genocide,[7][8] or the Syriac Genocide[9] (Syriac: ܩܛܠܥܡܐ ܣܘܪܝܝܐ, romanized: Qṭālʿammā Sūryāyā) was the mass slaughter and deportation of Syriac Christians in eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire, and neighbouring regions of Persia, commited by Ottoman troops[1][2] during the First World War. Considered a genocide by several scholars,[10][11][12] it occurred concurrently with the Armenian and Greek genocides.[13][14][15]

| Seyfo | |

|---|---|

| Part of the persecution of Assyrians | |

Map showing where the Seyfo was carried out, with deportation routes in red | |

| Location | |

| Date | 1914–1924 |

| Target | Syriac Christians |

Attack type | Deportation, mass murder, genocide, etc. |

| Deaths | 200,000–400,000 (see death toll section below) |

| Perpetrators | Young Turk government, Kurdish tribes[3] |

| Motive | Anti-Assyrian sentiment, anti-Christianity |

The Assyrian civilian population of upper Mesopotamia (the Tur Abdin region, the Hakkâri, Van, and Siirt provinces of present-day southeastern Turkey, and the Urmia region of northwestern Iran) was forcibly relocated and massacred by the Ottoman army, together with other armed and allied Muslim peoples, including Kurds and Circassians, between 1914 and 1920, with further attacks on unarmed fleeing civilians conducted by local Arab militias.[13]

The Seyfo is comparatively less well-studied than the Armenian genocide. Scholars such as Joseph Yacoub,[16] Gabriele Yonan,[17] David Gaunt and Hannibal Travis,[14] have classified the Seyfo as a systematic campaign by the Young Turk government. Other scholars, such as Hilmar Kaiser,[18] Donald Bloxham and Taner Akçam state that the killings of Assyrians lack the government planning and systematic nature of the Armenian Genocide. There were no orders to deport Assyrians; the attacks against them were not of a standardized nature and incorporated various methods; in some cities, all Assyrian men were slain and the women were forced to flee. These massacres were often carried out upon the initiatives of local politicians and Kurdish tribes. Exposure, disease and starvation during the flight of Assyrians increased the death toll, and women were subjected to widespread sexual abuse in some areas.

Estimates on the overall death toll have varied. Providing detailed statistics of the various estimates of the Churches' population after the genocide, David Gaunt accepts the figure of 275,000 deaths as reported by the Assyrian delegation at the Treaty of Lausanne and ventures that the death toll would be around 300,000 because of uncounted Assyrian-inhabited areas.[19]

Terminology

Terms for Syriac Christians such as "Assyrian" / "Syriac" / "Aramaic" / "Chaldean" have become controversial, notably in countries where significant diaspora communities exist such as Germany and Sweden, alternative terms such as Assyriska/syrianska/kaldeiska folkmordet "Assyrian/Syriac/Chaldean genocide" are employed. Nestorians, Syrians, Syriacs, and Chaldeans were names used by Western missionaries such as the Catholics and Protestants on the Ottoman and Persian Assyrians. The Greek, Persian, and Arab rulers of occupied Assyria, as well as Chaldean and Syriac Orthodox patriarchs, priests, and monks, and Armenian, British, and French laypeople, called them all Assyrians.[13]

The Assyrian genocide is sometimes also referred to as Sayfo or Seyfo in English-language sources, based on the modern Assyrian (Mesopotamian neo-Aramaic) designation Saypā (ܣܝܦܐ), "sword", pronounced as Seyfo or Sayfo in the Western dialect (the term abbreviates Syriac: ܫܢܬܐ ܕܣܝܦܐ, romanized: Šato d-Sayfo, "Year of the Sword"). The Assyrian name Qeṭlā d-ʿAmmā Āṯûrāyā (ܩܛܠܐ ܕܥܡܐ ܐܬܘܪܝܐ), which literally means "killing of the Assyrian people", is used by some groups to describe these events. The word qṭolamo (ܩܛܠܥܡܐ) which means "genocide" is also used in Assyrian diaspora media. The term used in Turkish media is Süryani Soykırımı.

Background

The Assyrian population in the Ottoman Empire numbered about one million at the turn of the twentieth century and was largely concentrated in what is now Iran, Iraq and Turkey.[13] However, researchers such as David Gaunt have noted that the Assyrian population was around 600,000 prior to World War I.[19] There were significantly larger communities located in the regions near Lake Urmia in Persia, Lake Van (specifically the Hakkari region) and Mesopotamia, as well as the eastern Ottoman vilayets of Diyarbekir, Erzurum and Bitlis. Like other Christians residing in the empire, they were treated as second-class citizens and denied public positions of power. Violence directed against them prior to the First World War was not new. Many Assyrians were subjected to Kurdish brigandage and even outright massacre and forced conversion to Islam, as was the case of the Assyrians of Hakkari during the massacres of Badr Khan in the 1840s and the Massacres of Diyarbakır during the 1895–96 Hamidian Massacres.[14] The Hamidiye received assurances from the Ottoman Sultan that they could kill Assyrians and Armenians with impunity, and were particularly active in Urhoy and Diyarbakir.[13]

Outbreak of war

The Ottoman Empire began massacring Assyrians in the nineteenth century, a time of friendly relations between the Ottomans and the British, who were defending the Ottomans from the Russian Empire's efforts to include under its protection the communities of Ottoman Orthodox Christians.[13] In October 1914, the Ottoman Empire began deporting and massacring Assyrians and Armenians in Van.[13] After attacking Russian cities and declaring war on Britain and France, the Empire declared a holy war on Christians.[13] The German Kaiser and the German Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire directed and orchestrated the holy war, and financed the Ottomans' war against the Russian Empire.[13]

Responsibility of the Ottoman government

The degree of the responsibility of the Ottoman government and whether the genocide had a systematic nature has been the subject of different scholarly opinions. Concerning the responsibility of the Ottoman government, Hilmar Kaiser wrote that Talaat Pasha ordered the deportations of the Assyrians in the area on 26 October 1914, fearing their collaboration with the advancing Russian troops, but the order was postponed and abandoned three days later due to a lack of forces. When the Assyrians did not collaborate with Russians, any plans to deport them were cancelled. Kaiser wrote that the massacres of Assyrians were apparently not a part of the official Ottoman policy and that the Assyrians were ordered to be treated differently from the Armenians.[20] Taner Akçam, a leading specialist in the Armenian Genocide, cites Ottoman official correspondence in 1919, inquiring the number and conditions of Assyrians deported, to state that the Ottoman government was unaware of the full numerical extent of the deportations of Assyrians. Another Ottoman document orders Assyrians to be detained in their present locations, instead of their deportation, which, according to Akçam, indicates that the Assyrian population could have been treated differently from the Armenians, but that they were often "eliminated" alongside them.[21] Donald Bloxham, a genocide scholar, stated that while Assyrians of western Persia, Hakkari, Bitlis, Van and Diarbekir were massacred along with Armenians, they were "not subject to the same systematic destruction".[22]

Dominik J. Schaller and Jürgen Zimmerer wrote that due to the lack of an international diaspora and a nation state, the Assyrian were perceived as more vulnerable and less threatening by the Young Turks, which led to their extermination being "less systematic". Massacres of Assyrians were often undertaken through the initiatives of local officials and groups. Nevertheless, they classified the campaign against Assyrians as having "genocidal quality".[23] Ernst II, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, the German special envoy in Constantinople, sent a report describing "systematic extermination" of the Christian population of the Diarbekir province by Reshid Bey, the governor. Martin Tamcke wrote that a German chargé d'affairs in Constantinople sent to the German Chancellery an article from a Young Turk-controlled newspaper, which mentioned the expulsion of Assyrians in the east as an example of the "cleansing of the empire of Christian elements". Tamcke wrote that documents such as these, along with oral traditions, are evidence of a systematic policy of extermination.[24]

David Gaunt compared the attacks on Assyrians in Hakkari and Diarbekir, and wrote that while the former was mainly perpetrated upon the orders of the Turkish government, the latter was a local initiative of CUP politicians unconnected with the central government, and with no orders to exterminate Assyrians in the area.[25]

Massacres

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

General characteristics

According to historian David Gaunt, a primary characteristic was the total targeting of the Assyrian population, including farming villages as well as rebelling mountain tribes. The killing in rural regions was more extensive, while some survived the massacres in cities; Gaunt states that this indicates that a primary aim was the confiscation of land. The property, villages and animals of the villagers were destroyed totally to prevent their return. Gaunt states that organized troops were tasked with killing and expelling Assyrians in Hakkari and Ottoman-controlled parts of Persia, as well as resisting villages.[26] There were also deportations of Assyrians.[21]

Gaunt wrote that there was no standardized way of killing. He cites accounts of killings at town halls, river rafts, tunnels, streets, and during the flight of the victims. The methods included stabbing, decapitation, drowning, shooting and stoning among others according to eyewitness accounts cited by Gaunt; these accounts also record local officers having collections of body parts, such as ears, noses and "female body parts".[27]

Percy Sykes, a British officer in Persia, wrote that the Assyrians would have been exterminated if they had not fled to Persia. However, starvation, disease and fatigue cost the lives of 65,000 more Assyrians on their way to Persia or once they had arrived there, according to Christoph Baumer.[27]

Diyarbekir

The earliest programs of extermination took place in the southern province of Diyarbekir, under the leadership of Reshid Bey.[14][28] A German Vice-Consul reported in July 1915 that Assyrians were being massacred in Diyarbekir Vilayet. A German Consul reported in September 1915 that the adult Christians of Diyarbakır, Harput, Mardin, and Viranşehir had been targeted, and also mentioned an Ottoman reign of terror in Urhoy.[13] According to the reports, the Assyrian population of Faysh Khabur was completely killed, along with all the male Assyrians of Mardin and Siirt. The widows and orphans of these men were reportedly left to flee to Mosul on foot, and died on their way due to starvation and harsh conditions. These atrocities prompted the Assyrian patriarch to appeal to the Russian representative in the Caucasus, claiming that the Turkish leaders were intent on killing all Assyrians.[29] The German ambassador reported that the Ottoman Empire was being "clear[ed]" of its indigenous Christians by "eliminat[ion]".[13] In July 1915, he confirmed that the Assyrians of Midyat, Nisibis, and Jazirah were also slain.[13]

According to the Syrian Patriarchate, the Turkish government ordered an attack on the Christian villages near Mardin, which were mostly inhabited by Assyrians. The soldiers went beyond attacking property and killed civilians, for instance, the Assyrians of Kızıltepe/Tell Armen were gathered in a church and burned. In Diyarbekir, women and children were deported, but only a very small number reached their destinations as women were killed, raped or sold.[30]

Individual accounts of the massacres include several villages. In the village of Cherang near Diyarbekir, 114 men were killed and the women and children were put to forced agricultural labor and given the choice to convert or die. The massacre was committed by an Al-Khamsin death squad, which were recruited by the government and led by officials, while composed of local urban Muslims.[31] In the village of Hanewiye, about 400 Assyrians are believed to have been murdered. In Hassana, a village near Jezire, the 300 inhabitants were massacred, with some managing to survive and flee. The inhabitants of the village of Kavel-Karre were attacked by Kurdish tribes on 19 June 1915 and killed; their bodies were then thrown into the Tigris River. In Kafarbe, 2 km from the Mor Gabriel Monastery, 200 Assyrians were attacked by a clan of Kurds and murdered in 1917. However, there were also cases when those in power chose to protect the Assyrians, as Rachid Osman, the agha of Şırnak protected the 300–500 inhabitants of Harbol.[32]

In their book The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, Viscount Bryce and Arnold Toynbee included a letter from the Presbyterian American Church in Urmia, sent on 6 March 1916, which related information from a survivor of the events described. In the document, it is written that nearly all of the 30,000 Assyrians (called "Nestorians") of the Bohtan region had been massacred by the Kurds and Turkish soldiers with the orders of the government. While some Kurdish leaders tried to protect the population, they were unable to as the order had allegedly come from the government and such friendly acts were punished. All Christian villages of the plain were reportedly "wiped out", including three Protestant villages. In Monsoria, one of these villages, Assyrian women reportedly jumped into the Tigris River to prevent their capture by the Kurds. The surviving women and children were taken as captives.[33]

Figures by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate presented to the peace conference after the war state that 77,963 Assyrians were killed in 278 villages of the Diyarbekir province.[34] Jean Naayem writes that about 50 villages close to Midyat were ruined and their Assyrian inhabitants slaughtered, but he does not name any of them nor give any casualty figures. However, the figure agrees with the data of the patriarchate.[35]

Van

In October 1914, 71 Assyrian men of Yüksekova/Gawar were arrested and taken to the local government center in Başkale and killed.[36] In November 1914, Russian troops briefly occupied the towns of Başkale and Saray, following their retreat, the Assyrian and Armenian populations of these areas were accused of collaboration and targeted for revenge. According to eyewitness accounts collected by Russians and local observers, at least twelve villages were "wiped out" in this period.[37]

Jevdet Pasha the governor of Van, is reported to have held a meeting in February 1915 at which he said, "We have cleansed the Armenians and Syriac [Christian]s from Azerbaijan, and we will do the same in Van."[38]

In late 1915, Jevdet Bey, Military Governor of Van Vilayet, upon entering Siirt (or Seert) with 8,000 soldiers whom he himself called "The Butchers' Battalion" (Turkish: Kasap Taburu),[14] ordered the massacre of almost 20,000 Assyrian civilians in at least 30 villages.

The same "butcher battalions" killed all the male Assyrian and Armenian population of Bitlis. They reportedly raped the women, and subsequently sold them or gave them as "gifts".[39]

The town of Sa'irt/Seert (modern-day Siirt), was populated by Assyrians and Armenians. Seert was the seat of a Chaldean Archbishop Addai Scher who was murdered by the Kurds.[40] The eyewitness Hyacinthe Simon wrote that 4,000 Christians died in Seert.[41]>[42] According to Joseph Naayem, who was an Assyrian priest, the number of Assyrians killed in the town of Seert/Siirt alone exceeded 8000. Eyewitness accounts state that the Assyrian men were rounded up by criminal gangs and forced to a march to the valley of Zeryabe, where they were killed. This was followed by the gangs' attack on women. The Ottoman officer Raphael de Nogales described a "slope [...] crowned by thousands of half-nude and still bleeding corpses, lying in heaps". He then wrote that when he entered Siirt, he saw that the police and the locals were sacking Christian homes, and learned that the governors of the town directed the massacre, which had been arranged beforehand.[27]

According to "the Blue Book" of the American government, widespread ethnic cleansing and massacres occurred against the Assyrians as well as Armenians in the Hakkari area, with the orders for the deportations of Armenians being misinterpreted as orders against all Christians by the local Kurds. It was reported that an attack was launched on Assyrian dwellings in summer 1915, and that Assyrians were attempted to be "starved out". According to Paul Shimmon and Arnold J. Toynbee, an Assyrian village called "Goele", with the population of 300, was attacked and its men were killed, while the women and children were forced into slavery and the houses were pillaged. In another village with fifty houses, the Kurds reportedly killed the entire civilian population. "The Blue Book" states that in one district of Hakkari, only 17 Christian survivors were left from 41 villages.[39] In April 1915, after a number of failed Kurdish attempts, Ottoman Troops invaded Gawar, a region of Hakkari, and massacred the entire population.[43] There were later reports of the mass killing of hundreds of Assyrians in the same area, and women being forced into sexual slavery.[39]

David Gaunt wrote that the Assyrians of the Hakkari area were targeted in a "full ethnic cleansing" and asserted that they "faced the full wrath of the Ottoman government as well as the local Kurdish tribes". He claimed that due to their consistent contact and collaboration with the Russians, they were targeted with atrocities, and after a battle in which they collaborated with the Russians to defeat the Ottoman Army, the army perpetrated the massacres against Christians in Başkale, Siirt and Bitlis described above. Talaat Pasha also allegedly ordered a policy in which Ottoman troops, with the support of Kurdish tribes, defeated Assyrians and drove them to the mountains, subsequently destroying their property.[25]

Assyrian resistance

Assyrian resistance in Tur Abdin

The Assyrian Syriac Christians of Diyarbekir Vilayet made significant resistance. Their strongest stand was at the villages of Azakh, Iwardo, and Basibrin. For month, Kurdish tribes and Turkish soldiers commanded by Ömer Naci Bey were unable to subdue the mostly Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Catholic Assyrian villagers who were joined by Armenian and other Assyrian refugees from surrounding villages. The leaders of the Azakh fedayeen swore

We all have to die sometime, do not die in shame and humiliation

and lived up to their fighting words.[44]

Assyrian resistance in Persia

The Assyrians in Persia armed themselves under the command of General Agha Petros, who had been approached by the Allies to help fight the Ottomans. They put up a resistance, and Agha Petros' volunteer army had quite a few successes over the Ottoman forces and their Kurdish allies, notably at Suldouze where 1,500 Assyrian horsemen overcame the far larger Ottoman force of over 8,000, commanded by Kheiri Bey. Agha Petros also defeated the Ottoman Turks in a major engagement at Sauj Bulak and drove them back to Rowanduz. Assyrian forces in Persia were greatly affected by the withdrawal of Russia from the war and the collapse of Armenian armed resistance in the region. They were left cut off, with no supplies, vastly outnumbered and surrounded.[13]

Assyrian resistance in Upper Mesopotamia

An Assyrian nation under British and Russian protection was promised the Assyrians first by Russian officers, and later confirmed by Captain Gracey of the British Intelligence Service. Based on these representations, the Assyrians of Hakkari, under their Mar Shimun XIX Benjamin and the Assyrian tribal chiefs "decided to side with the Allies, first with Russia, and next with the British, in the hope that they might secure after the victory, a self-government for the Assyrians."[45] The French also joined the alliance with the Assyrians, offering them 20,000 rifles, and the Assyrian army grew to 20,000 men co-led by Agha Petrus Elia of the Bit-Bazi tribe, and Malik Khoshaba of the Bit-Tiyari tribe, according to Joseph Naayem (a key witness, whose account on the atrocities was prefaced by Lord James Bryce).[46][47]

On 3 March 1918, the Ottoman army led by Kurdish soldiers assassinated one of the most important Assyrian leaders at the time. This resulted in the retaliation of the Assyrians. Malik Khoshaba of the Tyari tribe, alongside Assyrian military leader Agha Petros led a successful attack against the Ottomans. Assyrian forces in the region also attacked the Kurdish fortress of Simko Shikak, the leader who had assassinated Mar Shimun XIX Benyamin, they successfully stormed it, defeating the Kurds, however Simko escaped and fled.

Assyrians were involved in a number of clashes in Turkey with Ottoman forces, including Kurds and Circassians loyal to the empire. When armed and in sufficient numbers they were able to defend themselves successfully. However, they were often cut off in small pockets, vastly outnumbered and surrounded, and unarmed villagers made easy targets for Ottoman and Kurdish forces.

Events in Persia

Urmia and surroundings

The Ottoman Empire invaded northwestern Persia in 1914.[13] Before the end of 1914, Turkish and Kurdish troops had successfully entered the villages in and around Urmia. On 21 February 1915 the Turkish army in Urmia seized 61 leading Assyrians from the French missions as hostages, demanding large ransoms. The mission had enough money to convince the Ottomans to let 20 of the men go. However, on 22 February the remaining 41 were executed, having their heads cut off at the stairs of the Charbachsh Gate. The dead included bishop Mar Denkha.

Most of the Assyrian villages were unarmed. The only protection they had was when the Russian army finally took control of the area, years after the presence of the Ottoman army had been removed. On 25 February 1915, Ottoman troops stormed their way into the villages of Gulpashan and Salamas. Almost the entire village of Golpashan, of a population of 2,500, were massacred.[14] In Salmas, about 750 Armenian and Assyrian refugees were protected by Iranian civilians in the village. The commander of the Ottoman division stormed the houses despite the fact that Iranian Azerbaijanis lived in them, and roped all the men together in large groups and forced them to march in the fields between Khusrawa and Haftevan/Hafdewan. The men were shot or killed in other ways. The protection of Christians by local civilians (primarily Iranian Azerbaijanis) is also confirmed in the 1915 British report: "Many Moslems tried to save their Christian neighbours and offered them shelter in their houses, but the Turkish authorities were implacable."[36] According to American official accounts, the largest Assyrian village in the Urmia region was overrun and all its men killed, while the women were attacked. In Haftevan, the Russian troops later discovered more than 700 corpses, and The Washington Post also claimed the abduction of 500 Assyrian girls. According to similar reports, 200 Assyrians were killed by burning in a church.[39]

During the winter of 1915, 4,000 Assyrians died from disease, hunger, and exposure, and about 1000 were killed in the villages of Urmia.[13][48] According to Los Angeles Times, in Urmia alone, 800 Assyrians were massacred and 2000 died from disease. American documents report widespread sexual violence against Assyrian women of all ages and the looting and destruction of the houses of about five-sixths of the Assyrian population. Reports state that over 200 girls were forced into sexual slavery and conversion into Islam. Eugene Griselle from the Ethnological Society of Paris gives the figure of 8,500 for the number of deaths in the Urmia region; according to other reports, out of an Assyrian population of 30,000, one-fifth was killed, their villages and churches destroyed. An English priest in the area estimates the death toll at 6,000.[39]

However, David Gaunt wrote that the massacres were reciprocated by the Assyrians. Assyrian Jilu tribes were accused of committing massacres of local villagers in the plains of Salmas; local Iranian officials reported that between Khoi and Julfa, a great number of villagers were massacred.[49]

In 1918, the Assyrian population of Urmia was nearly wiped out, 1,000 killed in the French and American mission buildings, 200 surrounding villages destroyed, and thousands perished from disease, forced marches and the Persian famine of 1917–1919.[13]

In early 1918, many Assyrians started to flee present-day Turkey. Mar Shimun Benyamin had arranged for some 3,500 Assyrians to reside in the district of Khoi. Not long after settling in, Kurdish troops of the Ottoman Army massacred the population almost entirely. One of the few that survived was Reverend John Eshoo. After escaping, he stated:

You have undoubtedly heard of the Assyrian massacre of Khoi, but I am certain you do not know the details.

These Assyrians were assembled into one caravansary, and shot to death by guns and revolvers. Blood literally flowed in little streams, and the entire open space within the caravansary became a pool of crimson liquid. The place was too small to hold all the living victims waiting for execution. They were brought in groups, and each new group was compelled to stand over the heap of the still bleeding bodies and shot to death. The fearful place became literally a human slaughter house, receiving its speechless victims, in groups of ten and twenty at a time, for execution.

At the same time, the Assyrians, who were residing in the suburb of the city, were brought together and driven into the spacious courtyard of a house [...] The Assyrian refugees were kept under guard for eight days, without anything to eat. At last they were removed from their place of confinement and taken to a spot prepared for their brutal killing. These helpless Assyrians marched like lambs to their slaughter, and they opened not their mouth, save by sayings "Lord, into thy hands we commit our spirits. [...]

The executioners began by cutting first the fingers of their victims, join by joint, till the two hands were entirely amputated. Then they were stretched on the ground, after the manner of the animals that are slain in the Fast, but these with their faces turned upward, and their heads resting upon the stones or blocks of wood Then their throats were half cut, so as to prolong their torture of dying, and while struggling in the agony of death, the victims were kicked and clubbed by heavy poles the murderers carried Many of them, while still laboring under the pain of death, were thrown into ditches and buried before their souls had expired.

The young men and the able-bodied men were separated from among the very young and the old. They were taken some distance from the city and used as targets by the shooters. They all fell, a few not mortally wounded. One of the leaders went to the heaps of the fallen and shouted aloud, swearing by the names of Islam's prophets that those who had not received mortal wounds should rise and depart, as they would not be harmed any more. A few, thus deceived, stood up, but only to fall this time killed by another volley from the guns of the murderers.

Some of the younger and good looking women, together with a few little girls of attractive appearance, pleaded to be killed. Against their will were forced into Islam's harems. Others were subjected to such fiendish insults that I cannot possibly describe. Death, however, came to their rescue and saved them from the vile passions of the demons. The death toll of Assyrians totaled 2,770 men, women and children.[50]

Baquba camps

By mid-1918, the British army had convinced the Ottomans to let them have access to about 30,000 Assyrians from various parts of Persia. The British decided to relocate all 30,000 from Persia to Baquba, northern Iraq, in the hope that this would prevent further massacres. Many others had already left for northern Iraq after the Russian withdrawal and collapse of Armenian lines. The transferring took just 25 days, but at least 7,000 of them had died during the trip.[51] Some died of exposure, hunger or disease, other civilians fell prey to attacks from armed bands of Kurds and Arabs. At Baquba, Assyrians were forced to defend themselves from further Arab and Kurdish raids, which they were able to do successfully.

A memorandum from American Presbyterian Missionaries at Urmia During the Great War 16 to British Minister Sir Percy Cox had this to say:

Capt. Gracey doubtless talked rather big in the hopes of putting heart into the Assyrians and holding up this front against the Turks. [Consequently,] We have met all the orders issued by the late Dr. Shedd which have been presented to us and a very large number of Assyrian refugees are being maintained at Baquba, chiefly at H.M.G.'s expense.

In 1920, the British decided to close down the Baquba camps. The majority of Assyrians of the camp decided to go back to the Hakkari mountains, while the rest were dispersed throughout Iraq, where there was already an Assyrian community. However, they would again be targeted there in the 1933 Simele massacre.

Death toll

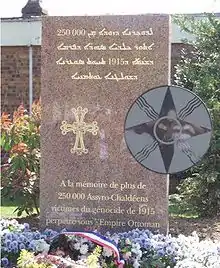

According to Benny Morris and Dror Ze'evi in The Thirty-Year Genocide, Assyrians who died at the hands of Muslims between 1914 and 1924 numbered "[s]ome 250,000, perhaps more".[44]

Scholars have summarized events as follows: specific massacres included 25,000 Assyrians in Midyat, 21,000 in Jezira-ibn-Omar, 7,000 in Nisibis, 7,000 in Urfa, 7,000 in the Qudshanis region, 6,000 in Mardin, 5,000 in Diyarbekir, 4,000 in Adana, 4,000 in Brahimie, and 3,500 in Harput.[14][39][52][53] In its 4 December 1922, memorandum, the Assyro-Chaldean National Council stated that the total death toll was unknown. It estimated that about 275,000 "Assyro-Chaldeans" died between 1914 and 1918.[54] The population of the Assyrians of the Ottoman Empire and Persia was about 600,000 before the genocide, and was reduced by 275,000, with very few survivors in 1930s Turkey or Iran.[13][55] Contemporary newspapers reported death tolls of 200,000 to 250,000.[39] Representatives from the Anglican Church in the region claimed that about half of the Assyrian population perished.[27]

Sabri Atman, the founder and director of the Assyrian Genocide and Research Center (Seyfo Center) explains that Assyrian leaders initially put the number of victims during the Assyrian genocide at 250,000 in the Ottoman empire and Persia. But later, the Assyrian delegation to the Lausanne peace talks in 1923 presented the number of victims as 275,000 after receiving more information on the total numbers of victims. According to some scholars, up to 400,000 in total perished at the hands of Ottoman state and their Kurdish allies.[56]

The memorandum of the Assyrian Archbishopric of Syria (Damascus-Homs) to the 1920 peace conference, places the death toll at 90,313 people, with 345 villages burned and 156 churches destroyed. The archbishop demanded 250,000 pounds sterling of reparations to compensate for the destruction of the churches. The figures of the archbishopric places the death toll in Harput at 3,500, in Midyat at 25,830, in Diyarbekir and surroundings at 5,679, in Jezireh at 7,510, in Nusaybin at 7,000, in Mardin at 5,815, in Bitlis at 850, in Urfa at 340, and tens of thousands at other areas. The archbishopric states that the Ottoman government undertook massacres of Assyrian civilians with "no revolutionary tendencies" in the provinces of Diyarbekir, Urfa, Van, Harput and Bitlis.[57]

Assyrians were not subject to genocidal policies to the extent of the Armenians. However, in some provinces, particularly Diyarbakır and Mardin, the Assyrian population was devastated. In other provinces the population was left relatively intact.

| Assyrian and Armenian population in Diyarbakır Province in 1915–1916[58] | |||||

| Sect | Before World War I | Disappeared (killed) | After World War I | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenians | Gregorians (Apostolic) | 60,000 | 58,000 (97%) | 2,000 | |

| Armenian Catholics | 12,500 | 11,500 (92%) | 1,000 | ||

| Assyrians | Chaldean Catholics | 11,120 | 10,010 (90%) | 1,110 | |

| Syriac Catholic | 5,600 | 3,450 (62%) | 2,150 | ||

| Syriac Orthodox | 84,725 | 60,725 (72%) | 24,000 | ||

| Protestants | 725 | 500 (69%) | 2,150 | ||

| Assyrian and Armenian population in Mardin province in 1915–1916[41] | |||||

| Sect | Before World War I | Disappeared (killed) | After World War I | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenians | Catholics | 10,500 | 10,200 (97%) | 300 | |

| Assyrians | Chaldean Catholics | 7,870 | 6,800 (86%) | 1,070 | |

| Syrian Catholic | 3,850 | 700 (18%) | 3,150 | ||

| Syrian Jacobite | 51,725 | 29,725 (58%) | 22,000 | ||

| Protestants | 525 | 250 (48%) | 275 | ||

Documented accounts of the genocide

Assyrians in what is now Turkey primarily lived in the provinces of Hakkari, Şırnak, and Mardin. These areas also had a sizable Kurdish population.

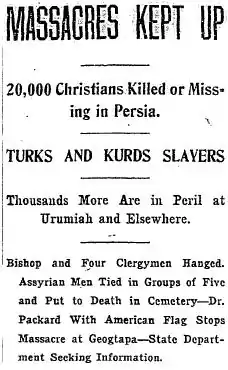

The following newspaper articles documented the Assyrian genocide as it occurred:

- "Assyrians Burned in Church", The Sun (Lowell, Massachusetts), 1915

- "Assyrians Massacred in Urmia", The San Antonio Light (San Antonio, Texas), 1915

- "Assyrians Massacred in Urmiah", The Salt Lake Tribune, 1915

- "Chaldean Victims of the Turks", The Times, 22 November 1919, p. 11

- "Christian Massacres in Urmiah", The Argus (Australia), 1915

- "Extermination of the Armenian Race", The Manchester Guardian, 1915

- "Massacres in Armenia", The Irish Times, 1915[59]

- "Help for Serbians and Armenians", The Irish Times, 1915[60]

- "Many Assyrian Perish", The Winnipeg Free Press, 1915

- "Massacred by Kurds; Christians Unable to Flee from Urmia Put to Death", The Washington Post, 14 March 1915, p. 10

- "Massacres of Nestorians in Urmia", The New York Times, 1915

- "Massacres Kept Up", The Washington Post, 26 March 1915, p. 1

- "Native Christians Massacred; Frightful Atrocities in Persia", Los Angeles Times, 2 April 1915, p I-1

- "Nestorian Christians Flee Urmia", The New York Times, 1915

- "Syrian Tells of Atrocities", Los Angeles Times, 15 December 1918, at I–1.

- "The Assyrian Massacres", The Manchester Guardian, 5 December 1918, at 4

- "The Suffering Serbs and Armenians", The Manchester Guardian, 1915, p5

- "Turkish Horrors in Persia", The New York Times, 11 October 1915

- "Turks Kill Christians in Assyria", Muscatine Journal (Muscatine, Iowa), 1915

- "Turkish Troops Massacring Assyrians, The Newark Advocate, 1915

A report published in the Washington Times on 26 March 1915.

A report published in the Washington Times on 26 March 1915. - "Turkish Horrors in Persia", The New York Times, 1915

- "The Total of Armenian and Syrian Dead", Current History: A Monthly Magazine of The New York Times', November 1916, 337–338

Hannibal Travis, Assistant Professor of Law at Florida International University, wrote in the peer-reviewed journal Genocide Studies and Prevention that:[39]

Numerous articles in the American press documented the genocide of Assyrians by the Turks and their Kurdish allies. By 1918, The Los Angeles Times carried the story of a Syrian, or most likely an Assyrian, merchant from Urmia who stated that his city was "completely wiped out, the inhabitants massacred", 200 surrounding villages ravaged, 200,000 of his people dead, and hundreds of thousands of more starving to death in exile from their agricultural lands. In an article entitled "Native Christians Massacred", the Associated Press correspondent reported that in the vicinity of Urmia, "Turkish regular troops and Kurds are persecuting and massacring Assyrian Christians". Close to 800 were confirmed dead in Urmia, and another 2,000 had perished from disease. Two hundred Assyrians had been burned to death inside a church, and the Russians had discovered more than 700 bodies of massacre victims in the village of Hafdewan outside Urmia, "mostly naked and mutilated", some with gunshot wounds, others decapitated, and still others carved to pieces.

Other leading British and American newspapers corroborated these accounts of the Assyrian genocide. The New York Times reported on 11 October that 12,000 Persian Christians had died of massacre, hunger, or disease; thousands of girls as young as seven had been raped or forcibly converted to Islam; Christian villages had been destroyed, and three-fourths of these Christian villages were burned to the ground.[61] The Times of London was perhaps the first widely respected publication to document the fact that 250,000 Assyrians and Chaldeans eventually died in the Ottoman genocide of Christians, a figure which many journalists and scholars have subsequently accepted.

Eyewitness accounts and quotes

Statement of German Missionaries on Urmia.

There was absolutely no human power to protect these unhappy people from the savage onslaught of the invading hostile forces. It was an awful situation. At midnight the terrible exodus began; a concourse of 25,000 men, women, and children, Assyrians and Armenians, leaving cattle in the stables, all their household hoods and all the supply of food for winter, hurried, panic-stricken, on a long and painful journey to the Russian border, enduring the intense privations of a foot journey in the snow and mud, without any kind of preparation. ... It was a dreadful sight, ... many of the old people and children died along the way.[62]

The latest news is that four thousand Assyrians and one hundred Armenians have died of disease alone, at the mission, within the last five months. All villages in the surrounding district with two or three exceptions have been plundered and burnt; twenty thousand Christians have been slaughtered in Armenia and its environs. In Haftewan, a village of Salmas, 750 corpses without heads have been recovered from the wells and cisterns alone. Why? Because the commanding officer had put a price on every Christian head... In Dilman crowds of Christians were thrown into prison and driven to accept Islam.[63]

Recognition

Assyrian historians attribute the limited recognition to the smaller number of Assyrian survivors, whose leader Mar Shimun XIX Benyamin was killed in 1918.[39] For example, there are one million Armenians living in the United States alone, but even they were unable to persuade Congress to pass a United States resolution on Armenian genocide until 2019. In addition, the widespread massacres of all Ottoman Christians in Asia Minor is sometimes referred to by Armenian authors as an "Armenian Genocide".

The Assyrian Policy Institute has released a map claiming that as of 2020, three American state legislatures (Arizona, California, and New York) have passed resolutions that officially recognize the Assyrian genocide. Ten other legislatures (Alabama, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Michigan, South Dakota, Tennessee, Washington D.C., and West Virginia) have passed resolutions that recognize the Armenian genocide, but acknowledge the Assyrian victims in their text.[65]

Timeline of recognition

- On 24 April 2001, Governor of the US state of New York, George Pataki, proclaimed that "killings of civilians and food and water deprivation during forced marches across harsh, arid terrain proved successful for the perpetrators of genocide, who harbored a prejudice against ... Assyrian Christians."[66]

- In December 2007, the International Association of Genocide Scholars, the world's leading genocide scholars organization, overwhelmingly passed a resolution officially recognizing the Assyrian genocide, along with the genocide against Ottoman Greeks.[67] The vote in favor was 83%. The Interparliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy (I.A.O.), passed a resolution officially recognizing the Assyrian genocide in June 2011.[68]

- In April 2008, David Paterson, the governor of New York, recognized the genocide.[69][70]

- On 11 March 2010, the genocide was officially recognized by the Riksdag of Sweden, alongside that of the Armenians and Pontic Greeks.[71][72][73]

- In May 2013, the Assyrian genocide was recognized by the New South Wales state parliament in Australia.[74][75]

- In March 2015, Armenia became the second country to recognize the Assyrian genocide in a declaration from the National Assembly which concurrently recognized the Greek genocide.[76]

- In April 2015, the parliaments of both Netherlands and Austria also recognized the Assyrian and Greek genocides.[77][78]

- On 2 June 2016, the German Bundestag recognized the genocides against the Armenian and Assyrian (also referred to as Syriacs, Chaldeans or Aramaic-speaking Christians) people.[79][80]

- On 1 November 2016, the state of Indiana recognized the Assyrian genocide under Governor Holcomb.[81]

- On 22 February 2018, the Dutch parliament recognized the Assyrian genocide for the second time.[82]

- In April 2018, the state of California recognized the Assyrian genocide on the 103rd anniversary of the Genocide Remembrance under Assembly Joint Resolution No. 37.[83][84]

- In February 2020, the parliament of Syria adopted a resolution that officially recognized the Assyrian and Armenian genocides.[85][86]

- In March 2020, the state of Arizona recognized the Assyrian Genocide under HCR 2006 and officially recognized 7 August as Assyrian Genocide Remembrance Day.[87][88][89][90]

Monuments

There are monuments commemorating the victims of the Assyrian genocide in France, Australia, Sweden, Armenia,[91] Belgium,[92] Greece and the United States. Sweden's government has pledged to pay for all the expenses of a future monument, after strong lobbying from the large Assyrian community there, led by Konstantin Sabo. There are three monuments in the U.S., one in Chicago, one in Columbia and the newest in Los Angeles, California.[93][94]

In August 2010, a monument to the victims was built in Fairfield City in Australia, a local government area of Sydney where one in ten of the population is of Assyrian descent. Designed by Lewis Batros, the statue is designed as a hand of a martyr draped in an Assyrian flag and stands at 4.5 meters tall. The memorial statue was proposed in August 2009. After conference with the community, Fairfield Council received more than 100 submissions for the memorial and two petitions.

The proposal has been condemned by the Australian Turkish community. Turkey's consul general to Sydney expressed resentment about the monument, while acknowledging that tragedies had occurred to Assyrians in the period as well as Turks.[95][96][97] On 30 August 2010, twenty-three days after it was unveiled, the Australian monument was vandalised.[98][99] The genocide monument in Sydney, Australia was vandalized again on the 15 April 2016, with the words "F**k Armenians, Assyrians and Jews" spray painted on the monument.[100][101]

_Osmanischer_Genozid.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Tarzana, California (2007)

Tarzana, California (2007)

Turkish perceptions

There are different perceptions in Turkey regarding the Assyrian genocide. The Armenian Turkish newspaper Agos has called the events the "Assyrian Genocide".[102] Turkish journalist Mehmet Alaca referred to the events as "Seyfo" in his 2012 article in Radikal and wrote that tens of thousands of Assyrians were murdered and expelled at the time.[103]

However, historian Bülent Özdemir of the Balıkesir University has pointed out to an "Assyrian rebellion" in Midyat in 1915, and said that the Ottoman Empire cannot be accused of committing a genocide against the Assyrians in any way, claiming that this was supported by documents in foreign archives. He claimed that the fabrication of such a genocide was part of an Assyrian identity-building process. In 2007, Turkish Assyrian Mıtra Hazail Soumi classified the events not as a genocide, but as a massacre.[104] Adriaan Wolvaardt wrote that "Turks view Assyrian allegations as unfounded, unproven and an attack on Turkish national identity" and that "Turks reject the Assyrian claims based on the stigma associated with the concept of genocide and their understanding of Turkish history".[105]

See also

- Armenian Genocide

- Armenian Genocide denial

- Assyrian independence movement

- Greek genocide

- Great Famine of Mount Lebanon

- List of Assyrian settlements

- Deportations of Kurds (1916–1934)

- Newspaper documentation of the Assyrian Genocide

- Stanley Savige

- Simele massacre

- The Last Assyrians

- William Ambrose Shedd

- Yusuf Akbulut

- Tel Aviv and Jaffa deportation

References

- Khosroeva 2007, pp. 270–271.

- Alexander Laban Hinton, Thomas La Pointe, Douglas Irvin-Erickson. Hidden Genocides: Power, Knowledge, Memory. p. 117. Rutgers University Press, 2013 ISBN 0813561647

- Khosroeva 2007, p. 271.

- Abdalla 2017, pp. 92–105.

- Yacoub 2016.

- Khosroeva 2018, pp. 61–70.

- Courtois 2004.

- Shabo 2019.

- Yacoub 2016, p. 30.

- Gaunt 2017, pp. 54–69.

- Demir 2017, pp. 106–136.

- Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, pp. 1–32.

- Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237–77, 293–294.

- Khosroeva 2007, pp. 267–274.

- Schaller, Dominik J. and Zimmerer, Jürgen (2008) "Late Ottoman Genocides: The Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish population and extermination policies." Journal of Genocide Research, 10:1, pp. 7–14.

- The Assyrian Question, Ed. Alpha Graphic, Chicago, 1986.

- Ein Vergessener Holocaust, Reihe Bedröhte Völker, Pogrom, Göttingen-Vienne, 1989.

- Kaiser, Hilmar (2010). "Genocide at the Twilight of the Ottoman Empire". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 371–372. ISBN 9780199232116.

Their killing appears, however, not to have been part of a central government policy. The provincial authorities were repeatedly instructed to treat Syrian Orthodox differently than Armenians.

- David Gaunt, "The Assyrian Genocide of 1915", Assyrian Genocide Research Center, 2009

- Kaiser, Hilmar (2010). "Genocide at the Twilight of the Ottoman Empire". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191613616. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. xx-xxi. ISBN 9781400841844. – Accessed on Google Books on 26 February 2015.

- Bloxham, Donald (2003). "Determinants of the Armenian Genocide". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). Looking Backward, Moving Forward: Confronting the Armenian Genocide (2 ed.). Transaction Publishers. p. 34. ISBN 9781412827676.

- Schaller, Dominik J.; Zimmerer, Jürgen (2012). Late Ottoman Genocides: The Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish Population and Extermination Policies. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 9781317990451.

- Tamcke, Martin (2012). "The Collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the "Seyfo" against the Syrians". In Tozman, Markus K.; Tyndall, Andrea (eds.). The Slow Disappearance of the Syriacs from Turkey and of the Grounds of the Mor Gabriel Monastery. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 20–22. ISBN 9783643902689.

- Gaunt, David (2013). Bartov, Omer; Weitz, Eric D. (eds.). Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands (illustrated ed.). Indiana University Press. p. 326. ISBN 9780253006318.

- Gaunt, David. "The Ottoman Treatment of Assyrians" in Grigor Suny, Ronald; Muge Gogek, Fatma; Naimark, Norman M., eds. (2011). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 245. ISBN 9780199781041. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 9781136937965. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- See David Gaunt, "Death's End, 1915: The General Massacres of Christians in Diarbekir" in Armenian Tigranakert/Diarbekir and Edessa/Urfa. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series: Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, 6. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2006, pp. 309–359.

- Travis, Hannibal. "The Assyrian Genocide: A Tale of Oblivion and Denial" in Lemarchand, Rene (2011). Forgotten Genocides: Oblivion, Denial, and Memory. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780812204384. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

assyrian massacres mardin.

- Courtois 2004, p. 248.

- Gaunt, David. "Relations Between Kurds and Syriacs and Assyrians" in Jongerden, Joost; Verheij, Jelle, eds. (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915. Brill. p. 263. ISBN 9789004225183. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Gaunt, Beṯ-Şawoce & Donef 2006, pp. 216–235.

- The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Hodder and Stoughton. 1916. pp. 180–181.

- Courtois 2004, p. 196.

- Courtois 2004, p. 199.

- Bryce, James Lord. "British Government Report on the Armenian Massacres of April–December 1915". Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- Gaunt, David. "The Ottoman Treatment of Assyrians" in Grigor Suny, Ronald; Muge Gogek, Fatma; Naimark, Norman M., eds. (2011). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 250. ISBN 9780199781041. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- Akçam, Taner. A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006, p. 201. ISBN 0805079327.

- Travis, Hannibal. "'Native Christians Massacred': The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians During World War I." Genocide Studies and Prevention, Vol. 1, No. 3, December 2006, pp. 327–371. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- Ara Sarafian.

- Gaunt, Beṯ-Şawoce & Donef 2006, p. 436.

- Ternon, Yves. Mardin 1915. Paris: Center for Armenian History, 2000. Accessed 2010-02-02.

- "The Plight of Assyria." The New York Times, 18 September 1916. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- Morris & Ze'evi 2019, p. 373.

- Yusuf Malik, The British Betrayal of the Assyrians (1935)

- Paul Bartrop, Encountering Genocide: Personal Accounts from Victims, Perpetrators, and Witnesses, ABC-CLIO, 2014

- Naayem, Shall This Nation Die?, p. 281

- "Information Quarterly". google.com. 1915.

- Gaunt, Beṯ-Şawoce & Donef 2006, p. 104.

- Joel Euel Werda. The Flickering Light of Asia: Or, the Assyrian Nation and Church Archived 2005-12-25 at the Wayback Machine, ch. 26.

- Austin, H. H.(Brig.-Gen.). The Baquba Refugee Camp – An account of the work on behalf of the persecuted Assyrian Christians. London, 1920.

- Gaunt, Beṯ-Şawoce & Donef 2006, pp. 76–77, 164, 181–196, 226–230, 264–267.

- (in German) Gorgis, Amill "Der Völkermord an den Syro-Aramäern," in Verfolgung, Vertreibung und Vernichtung der Christen im Osmanischen Reich 20. Ed. Tessa Hoffman. London and Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2004.

- (in French) Yacoub, Joseph. La question assyro-chaldéenne, les Puissances européennes et la SDN (1908–1938), 4 vol., thèse Lyon, 1985, p. 156.

- Gaunt, Beṯ-Şawoce & Donef 2006, pp. 21–28, 300–303, 406, 435.

- Remembering the Assyrian Genocide: An Interview with Sabri Atman

- Courtois 2004, p. 237.

- Gaunt, Beṯ-Şawoce & Donef 2006, p. 433.

- The Irish Times (Saturday, 4 December 1915), p. 11.

- The Irish Times (Saturday, 18 December 1915), p. 3.

- "Turkish Horrors in Persia". The New York Times. 11 October 1915. p. 4. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- Yohannan, Abraham. The Death of a Nation: Or, The Ever Persecuted Nestorians or Assyrian Christians. London: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1916, pp. 119–120. ISBN 0524062358.

- Yohannan. The Death of a Nation, pp. 126–127.

- Call for Architectural Sketches for Assyrian Genocide Monument in Yerevan, Armenia. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- "Assyrian Genocide Recognition in the United States". Assyrian Policy Institute. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "New York State Governor Proclamation". 1 April 2001. Retrieved 16 June 2006.

- Jones, Adam (15 December 2007). "International Genocide Scholars Association Officially Recognizes Assyrian, Greek Genocides". AINA. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- "Seyfocenter". Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- State of New York, Gov. David Paterson, Proclamation Archived 2010-01-08 at the Wayback Machine, 24 April 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "Governor Pataki Commemorates Armenian Genocide". Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 24 January 2010.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link), Proclamation, 5 May 2004. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "Motion 2008/09:U332 Genocide of Armenians, Assyrians/Syriacs/Chaldeans and Pontiac Greeks in 1915". Stockholm: The Riksdag. 11 March 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- "Sweden to recognize Armenian genocide". The Local. 11 March 2010. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- "Sweden Recognizes Assyrian, Greek and Armenian Genocide." Assyrian International News Agency. 12 March 2010.

- "NSW Parliament formally recognises Assyrian genocide as Smithfield MP Andrew Rohan shares tale of parents' survival". The Daily Telegraph. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Consultation Paper for Proposed Memorial Dedicated to the Victims of the Assyrian Genocide Archived 2011-03-12 at the Wayback Machine." Fairfield City Council.

- "Adoption of declaration to certify Armenia recognizes Greek and Assyrian genocides: Eduard Sharmanazov". Armenpress. 23 March 2015.

- "Dutch Parliament Recognizes Assyrian, Greek and Armenian Genocide". Assyrian International News Agency. 10 April 2015.

- "Austrian Parliament Recognizes Armenian, Assyrian, Greek Genocide". Assyrian International News Agency. 22 April 2015.

- "German Recognition of Armenian, Assyrian Genocide: History and Politics". www.aina.org.

- Smale, Alison; Eddy, Melissa (2 June 2016). "German Parliament Recognizes Armenian Genocide, Angering Turkey". The New York Times.

- "Indiana Becomes 48th State to Recognize the Armenian Genocide". 6 November 2017.

- "Dutch parliament recognizes 1915 Armenian 'genocide' | DW | 22.02.2018".

- "California Recognizes Assyrian Genocide".

- "Rules Committee Agenda" (PDF). Assembly Rules Committee. 19 April 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Syria Passes Resolution Condemning Turkish Genocide of Assyrians, Armenians". Assyrian International News Agency. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Syrian Parliament Adopts Resolution Recognizing the Armenian Genocide". Massis Post. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "The State of Arizona Recognizes the Assyrian Genocide". Seyfo Center. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "HCR 2006". Arizona State Legislature. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Assyrian Genocide Resolution Read in Arizona Assembly". Assyrian International News Agency. 3 March 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "HCR 2006". Track Bill. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Shahen, Hermiz (6 May 2012). "The unveiling of the Assyrian genocide monument in Armenia Representatives of the Assyrian community". Seyfo Center. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "The Assyrian Genocide Monument in Belgium". aina.org.

- "Assyrian Genocide Monument Unveiled in Australia".

- "The Genocide of Greeks, 1914–1923". greek-genocide.org. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012.

- "Turkey protests Assyrian 'genocide' monument". Today's Zaman. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- Fairfield City Champion, 16 December 2009.

- "Assyrian Genocide Monument Unveiled in Australia". Assyrian International News Agency. 8 July 2010. Archived from the original on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- "Assyrian Genocide Monument in Australia Vandalized". Assyrian International News Agency. 30 August 2010. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- "Assyrian memorial vandalised". Fairfield Champion. 30 August 2010. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- Aubusson, Kate (16 April 2015). "Assyrian memorial in Bonnyrigg vandalised" – via The Sydney Morning Herald.

- "Assyrian Genocide Monument Vandalized 2015 – Assyrian Universal Alliance". aua.net. 16 April 2015.

- "Seyfo'nun 100. Yılında Süryaniler harekete geçiyor" (in Turkish). Agos. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Alaca, Mehmet (30 November 2012). "Mezopotamya'nın kadim talihsizleri" (in Turkish). Radikal. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Yağcı, Zübeyde Güneş. "BÜLENT ÖZDEM R, Süryanilerin Dünü Bugünü I. Dünya Sava ında Süryaniler" (PDF). Turkish Historical Society. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Wolvaardt, Adriaan (2014). Yasmeen, Samina; Markovic, Nina (eds.). Muslim Citizens in the West: Spaces and Agents of Inclusion and Exclusion. Ashgate Publishing. p. 118. ISBN 9780754677833.

Sources

- Abdalla, Michael (2017). "The Term Seyfo in Historical Perspective". The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 92–105. ISBN 9781138284050.

- Atman, Sabri (2018). "Assyrian Genocide from a Gender Perspective". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 215–232. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Atto, Naures; Barthoma, Soner O. (2017). "Syriac Orthodox Leadership in the Post-Genocide Period (1918–26) and the Removal of the Patriarchate from Turkey". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. New York-Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 113–131. ISBN 9781785334993.

- Bar Abraham, Abdulmesih (2017). "Turkey's Key Arguments in Denying the Assyrian Genocide". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 219–232. ISBN 9781785334993.

- Bar Abraham, Abdulmesih (2018). "German Perceptions of the Sayfo: How Much Did Germany Know?". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 71–88. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Bednarowicz, Sebastian (2018). "Before and After Linguicide: A Linguistic Aspect of the Sayfo". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 365–384. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Beth Yuhanon, Basna (2018). "The Methods of Killing Used in the Assyrian Genocide". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 177–214. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Birol, Simon (2018). "Forgotten Witnesses: Remembering and Interpreting the Sayfo in the Manuscripts of Tur 'Abdin". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 327–346. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Çetinoğlu, Sait (2017). "Genocide/Seyfo and How Resistance Became a Way of Life". The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 178–190. ISBN 9781138284050.

- Courtois, Sebastien de (2004). The Forgotten Genocide: Eastern Christians, the Last Aramaeans. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 9781593330774.

- Demir, Sara (2017). "The Atrocities against the Assyrians in 1915: A Legal Perspective". The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 106–136. ISBN 9781138284050.

- Donef, Racho (2017). "Sayfo and Denialism: A New Field of Activity for Agents of the Turkish Republic". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. New York-Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 205–218. ISBN 9781785334993.

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453–1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521027007.

- Gaunt, David; Beṯ-Şawoce, Jan; Donef, Racho (2006). Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia During World War I. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 9781593333010.

- Gaunt, David; Atto, Naures; Barthoma, Soner O. (2017). "Introduction: Contextualizing the Sayfo in the First World War". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. New York-Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 1–32. ISBN 9781785334993.

- Gaunt, David (2017). "Sayfo Genocide: The Culmination of an Anatolian Culture of Violence". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. New York-Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 54–69. ISBN 9781785334993.

- "Death's End, 1915: The General Massacres of Christians in Diarbekir" in Armenian Tigranakert/Diarbekir and Edessa/Urfa. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series: Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, 6. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2006

- Halo, Thea (2018). "The Targeting of Assyrians during the Christian Holocaust in Ottoman Turkey". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 41–60. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Hellot-Bellier, Florence (2018). "The Increasing Violence and the Resistance of Assyrians in Urmia and Hakkari (1900–1915)". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 107–134. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Hofmann, Tessa (2018). "The Ottoman Genocide of 1914–1918 against Aramaic-Speaking Christians in Comparative Perspective". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 21–40. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Khosroeva, Anahit (2007). "The Assyrian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire and Adjacent Territories". The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. New Brunswick: New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. pp. 267–274. ISBN 9781412835923.

- Khosroeva, Anahit (2017). "The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians in Persia". The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 106–136. ISBN 9781138284050.

- Khosroeva, Anahit (2018). "The Significance of the Assyrian Genocide after a Century". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 61–70. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Makko, Aryo (2017). "The Assyrian Concept of Unity after Seyfo". The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 239–253. ISBN 9781138284050.

- Malek-Yonan, Rosie (2005). The Crimson Field. Pearlida Publishing. ISBN 0977187349.

- Morris, Benny; Ze'evi, Dror (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674916456.

- Mutlu-Numansen, Sofia; Ossewaarde, Marinus (2019). "A Struggle for Genocide Recognition: How the Aramean, Assyrian, and Chaldean Diasporas Link Past and Present" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 33 (3): 412–428. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcz045.

- Naby, Eden (2017). "Abduction, Rape and Genocide: Urmia's Assyrian Girls and Women". The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 158–177. ISBN 9781138284050.

- Ramadan Sonyel, Salahi (2001). The Assyrians of Turkey: Victims of Major Power Policy. Turkish Historical Society Printing House. ISBN 9751612969.

- Sato, Noriko (2018). "The Memory of Sayfo and its Relation to the Identity of Contemporary Assyrian/Aramean Christians in Syria". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 305–326. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Stafford, Ronald Sempill (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 1593334133.

- Shahbaz, Yonan (2006). The Rage of Islam: An Account of the Massacres of Christians by the Turks in Persia. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 1593334117.

- Travis, Hannibal (December 2006). "'Native Christians Massacred': The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians During World War I". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 1 (3): 327–371. doi:10.3138/YV54-4142-P5RN-X055.

- Andrieu, C; Sémelin, J; Gensburger, S (2010). Resisting Genocide: The Multiple Forms of Rescue. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231701723..

- Shabo, Johnny (2019). A Brief History of the Genocide Against the Syriac Arameans. Enschede: Independently Published. ISBN 9781075564338.

- Talay, Shabo (2017). "Sayfo, Firman, Qafle: The First World War from the Perspective of Syriac Christians". Let Them Not Return: Sayfo - The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. New York-Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 132–147. ISBN 9781785334993.

- Talay, Shabo (2018). "The Beginning of the End of Syriac Christianity in the Middle East". Sayfo 1915: An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 1–18. ISBN 9781463207304.

- Üngör, Uğur (2005). CUP Rule in Diyarbekir Province, 1913–1923 (PDF) (Thesis). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012.

- Wigram, W. A. (2002). The Assyrians and Their Neighbours. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 1-931956-11-1.

- Claire Weibel Yacoub, "Le rêve brisé des Assyro-Chaldéens", Editions du Cerf, Paris, 2011; "Surma l'Assyro-Chaldéenne (1883–1975), Dans la tourmente de Mésopotamie", Editions l'Harmattan, Paris, 2007, translated into Arabic.

- Joseph Yacoub (1986) The Assyrian question, Alpha graphic, Chicago, republished with additional elements in 2003, translated into Arabic and Turkish.

- Yacoub, Joseph (2016). Year of the Sword: The Assyrian Christian Genocide: A History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190633462.

- Naayem, Joseph (1921). Shall this Nation Die?. 2 December 2008 (digitized). Chaldean rescue. YouTube: FSi2OL_BJvY (incomplete).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Seyfo |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Assyrian Genocide. |

_(14760129156).jpg.webp)