Rhodocene

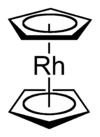

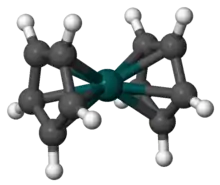

Rhodocene is a chemical compound with the formula [Rh(C5H5)2]. Each molecule contains an atom of rhodium bound between two planar aromatic systems of five carbon atoms known as cyclopentadienyl rings in a sandwich arrangement. It is an organometallic compound as it has (haptic) covalent rhodium–carbon bonds.[2] The [Rh(C5H5)2] radical is found above 150 °C or when trapped by cooling to liquid nitrogen temperatures (−196 °C). At room temperature, pairs of these radicals join via their cyclopentadienyl rings to form a dimer, a yellow solid.[1][3][4]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Rhodocene | |

| Other names

bis(cyclopentadienyl)rhodium(II) dicyclopentadienylrhodium | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H10Rh | |

| Molar mass | 233.095 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | yellow solid (dimer)[1] |

| Melting point | 174 °C (345 °F; 447 K) with decomposition (dimer)[1] |

| somewhat soluble in dichloromethane (dimer)[1] soluble in acetonitrile[1] | |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

ferrocene, cobaltocene, iridocene, bis(benzene)chromium |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

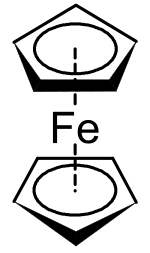

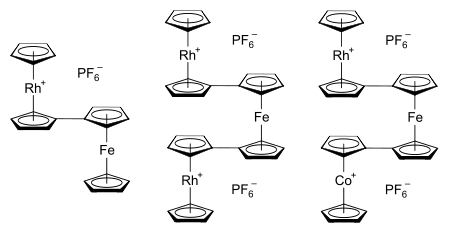

The history of organometallic chemistry includes the 19th-century discoveries of Zeise's salt[5][6][7] and nickel tetracarbonyl.[2] These compounds posed a challenge to chemists as the compounds did not fit with existing chemical bonding models. A further challenge arose with the discovery of ferrocene,[8] the iron analogue of rhodocene and the first of the class of compounds now known as metallocenes.[9] Ferrocene was found to be unusually chemically stable,[10] as were analogous chemical structures including rhodocenium, the unipositive cation of rhodocene[Note 1] and its cobalt and iridium counterparts.[11] The study of organometallic species including these ultimately led to the development of new bonding models that explained their formation and stability.[12][13] Work on sandwich compounds, including the rhodocenium-rhodocene system, earned Geoffrey Wilkinson and Ernst Otto Fischer the 1973 Nobel Prize for Chemistry.[14][15]

Owing to their stability and relative ease of preparation, rhodocenium salts are the usual starting material for preparing rhodocene and substituted rhodocenes, all of which are unstable. The original synthesis used a cyclopentadienyl anion and tris(acetylacetonato)rhodium(III);[11] numerous other approaches have since been reported, including gas-phase redox transmetalation[16] and using half-sandwich precursors.[17] Octaphenylrhodocene (a derivative with eight phenyl groups attached) was the first substituted rhodocene to be isolated at room temperature, though it decomposes rapidly in air. X-ray crystallography confirmed that octaphenylrhodocene has a sandwich structure with a staggered conformation.[18] Unlike cobaltocene, which has become a useful one-electron reducing agent in research,[19] no rhodocene derivative yet discovered is stable enough for such applications.

Biomedical researchers have examined the applications of rhodium compounds and their derivatives in medicine[20] and reported one potential application for a rhodocene derivative as a radiopharmaceutical to treat small cancers.[21][22] Rhodocene derivatives are used to synthesise linked metallocenes so that metal–metal interactions can be studied;[23] potential applications of these derivatives include molecular electronics and research into the mechanisms of catalysis.[24] The value of rhodocenes tends to be in the insights they provide into the bonding and dynamics of novel chemical systems, rather than their applications.

History

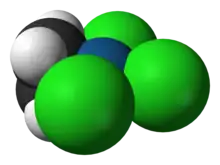

Discoveries in organometallic chemistry have led to important insights into chemical bonding. Zeise's salt, K[PtCl3(C2H4)]·H2O, was reported in 1831[5] and Mond's discovery of Ni(CO)4 occurred in 1888.[27] Each contained a bond between a metal centre and small molecule, ethylene in the case of Zeise's salt and carbon monoxide in the case of nickel tetracarbonyl.[6] The space-filling model of the anion of Zeise's salt (image at left)[25][26] shows direct bonding between the platinum metal centre (shown in blue) and the carbon atoms (shown in black) of the ethylene ligand; such metal–carbon bonds are the defining characteristic of organometallic species. Bonding models were unable to explain the nature of such metal–alkene bonds until the Dewar–Chatt–Duncanson model was proposed in the 1950s.[12][7][28][29] The original formulation covered only metal–alkene bonds[27] but the model was expanded over time to cover systems like metal carbonyls (including [Ni(CO)4]) where π backbonding is important.[29]

Ferrocene, [Fe(C5H5)2], was first synthesised in 1951 during an attempt to prepare the fulvalene (C10H8) by oxidative dimerization of cyclopentadiene; the resultant product was found to have molecular formula C10H10Fe and reported to exhibit "remarkable stability".[10] The discovery sparked substantial interest in the field of organometallic chemistry,[8][9] in part because the structure proposed by Pauson and Kealy (shown at right) was inconsistent with then-existing bonding models and did not explain its unexpected stability. Consequently, the initial challenge was to definitively determine the structure of ferrocene in the hope that its bonding and properties would then be understood. The sandwich structure was deduced and reported independently by three groups in 1952: Robert Burns Woodward and Geoffrey Wilkinson investigated the reactivity in order to determine the structure[30] and demonstrated that ferrocene undergoes similar reactions to a typical aromatic molecule (such as benzene),[31] Ernst Otto Fischer deduced the sandwich structure and also began synthesising other metallocenes including cobaltocene;[32] Eiland and Pepinsky provided X-ray crystallographic confirmation of the sandwich structure.[33] Applying valence bond theory to ferrocene by considering an Fe2+ centre and two cyclopentadienide anions (C5H5−), which are known to be aromatic according to Hückel's rule and hence highly stable, allowed correct prediction of the geometry of the molecule. Once molecular orbital theory was successfully applied, the reasons for ferrocene's remarkable stability became clear.[13]

The properties of cobaltocene reported by Wilkinson and Fischer demonstrated that the unipositive cobalticinium cation [Co(C5H5)2]+ exhibited stability similar to that of ferrocene itself. This observation is not unexpected given that the cobalticinium cation and ferrocene are isoelectronic, although the bonding was not understood at the time. Nevertheless, the observation led Wilkinson and F. Albert Cotton to attempt the synthesis of rhodocenium[Note 1] and iridocenium salts.[11] They reported the synthesis of numerous rhodocenium salts, including those containing the tribromide ([Rh(C5H5)2]Br3), perchlorate ([Rh(C5H5)2]ClO4), and reineckate ([Rh(C5H5)2] [Cr(NCS)4(NH3)2]·H2O) anions, and found that the addition of dipicrylamine produced a compound of composition [Rh(C5H5)2] [N(C6H2N3O6)2].[11] In each case, the rhodocenium cation was found to possess high stability. Wilkinson and Fischer went on to share the 1973 Nobel Prize for Chemistry "for their pioneering work, performed independently, on the chemistry of the organometallic, so called sandwich compounds".[14][15]

The stability of metallocenes can be directly compared by looking at the reduction potentials of the one-electron reduction of the unipositive cation. The following data are presented relative to the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) in acetonitrile:

- [Fe(C5H5)2]+ / [Fe(C5H5)2] +0.38 V[34]

- [Co(C5H5)2]+ / [Co(C5H5)2] −0.94 V[1]

- [Rh(C5H5)2]+ / [Rh(C5H5)2] −1.41 V[1]

These data clearly indicate the stability of neutral ferrocene and the cobaltocenium and rhodocenium cations. Rhodocene is ca. 500 mV more reducing than cobaltocene, indicating that it is more readily oxidised and hence less stable.[1] An earlier polarographic investigation of rhodocenium perchlorate at neutral pH showed a cathodic wave peak at −1.53 V (versus SCE) at the dropping mercury electrode, corresponding to the formation rhodocene in solution, but the researchers were unable to isolate the neutral product from solution. In the same study, attempts to detect iridocene by exposing iridocenium salts to oxidising conditions were unsuccessful even at elevated pH.[11] These data are consistent with rhodocene being highly unstable and may indicate that iridocene is even more unstable still.

Speciation

The 18-electron rule is the equivalent of the octet rule in main group chemistry and provides a useful guide for predicting the stability of organometallic compounds.[35] It predicts that organometallic species "in which the sum of the metal valence electrons plus the electrons donated by the ligand groups total 18 are likely to be stable."[35] This helps to explain the unusually high stability observed for ferrocene[10] and for the cobalticinium and rhodocenium cations[32] – all three species have analogous geometries and are isoelectronic 18-valence electron structures. The instability of rhodocene and cobaltocene are also understandable in terms of the 18-electron rule, in that both are 19-valence electron structures; this explains early difficulties in isolating rhodocene from rhodocenium solutions.[11] The chemistry of rhodocene is dominated by the drive to attain an 18-electron configuration.

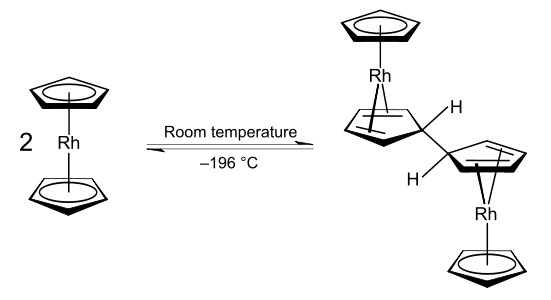

Rhodocene exists as [Rh(C5H5)2], a paramagnetic 19-valence electron radical monomer only at or below −196 °C (liquid nitrogen temperatures) or above 150 °C in the gas phase.[1][3][4] It is this monomeric form that displays the typical staggered metallocene sandwich structure. At room temperature (25 °C), the lifetime of the monomeric form in acetonitrile is less than two seconds;[1] and rhodocene forms [Rh(C5H5)2]2, a diamagnetic 18-valence electron bridged dimeric ansa-metallocene structure.[36] Electron spin resonance (ESR), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and infrared spectroscopic (IR) measurements point to the presence of an equilibrium interconverting the monomeric and dimeric forms.[4] ESR evidence confirms that the monomer possesses a high order axis of symmetry (Cn, n > 2) with a mirror plane (σ) perpendicular to it as symmetry elements; this experimentally demonstrates that the monomer does possess the typical sandwich structure of a metallocene[3][Note 2] although the interpretation of the ESR data has been questioned.[36] The decomposition pathway of the monomer has also been studied by mass spectrometry.[37] The dimerisation is a redox process; the dimer is a rhodium(I) species and the monomer has a rhodium(II) centre.[Note 3] Rhodium typically occupies oxidation states +I or +III in its stable compounds.[38]

This dimerisation process has the overall effect of decreasing the electron count around the rhodium centre from 19 to 18. This occurs because the oxidative coupling of the two cyclopentadienyl ligands produces a new ligand with lower hapticity and which donates fewer electrons to the metal centre. The term hapticity is used to indicate the "number of carbon (or other) atoms through which [a ligand] binds (n)"[39] to a metal centre and is symbolised as ηn. For example, the ethylene ligand in Zeise's salt is bound to the platinum centre through both carbon atoms, and it hence formally has the formula K[PtCl3(η2-C2H4)]·H2O.[6] The carbonyl ligands in nickel tetracarbonyl are each bound through only a carbon atom and are hence described as monohapto ligands, but η1-notations are typically omitted in formulae. The cyclopentadienyl ligands in many metallocene and half-sandwich compounds are pentahapto ligands, hence the formula [Rh(η5-C5H5)2] for the rhodocene monomer. In the rhodocene dimer, the coupled cyclopentadienyl ligands are 4-electron tetrahapto donors to each rhodium(I) metal centre, in contrast to the 6-electron[Note 4] pentahapto cyclopentadienyl donors. The increased stability of the 18-valence electron rhodium(I) dimer species as compared to the 19-valence electron rhodium(II) monomer likely explains why the monomer is only detected under extreme conditions.[1][4]

Cotton and Wilkinson demonstrated[11] that the 18-valence electron rhodium(III) rhodocenium cation [Rh(η5-C5H5)2]+ can be reduced in aqueous solution to the monomeric form; they were unable to isolate the neutral product as not only can it dimerise, the rhodium(II) radical monomer can also spontaneously form the mixed-hapticity stable rhodium(I) species [(η5-C5H5)Rh(η4-C5H6)].[3] The differences between rhodocene and this derivative are found in two areas: (1) One of the bound cyclopentadienyl ligands has formally gained a hydrogen atom to become cyclopentadiene, which remains bound to the metal centre but now as a 4-electron η4- donor. (2) The rhodium(II) metal centre has been reduced to rhodium(I). These two changes make the derivative an 18-valence electron species. Fischer and colleagues hypothesised that the formation of this rhodocene derivative might occur in separate protonation and reduction steps, but published no evidence to support this suggestion.[3] (η4-Cyclopentadiene)(η5-cyclopentadienyl)rhodium(I), the resulting compound, is an unusual organometallic complex in that it has both a cyclopentadienyl anion and cyclopentadiene itself as ligands. It has been shown that this compound can also be prepared by sodium borohydride reduction of a rhodocenium solution in aqueous ethanol; the researchers who made this discovery characterised the product as biscyclopentadienylrhodium hydride.[40]

Fischer and co-workers also studied the chemistry of iridocene, the third transition series analogue of rhodocene and cobaltocene, finding the chemistry of rhodocene and iridocene are generally similar. The synthesis of numerous iridocenium salts including the tribromide and hexafluorophosphate have been described.[4] Just as with rhodocene, iridocene dimerises at room temperature but a monomer form can be detected at low temperatures and in gas phase and IR, NMR, and ESR measurements indicate a chemical equilibrium is present and confirm the sandwich structure of the iridocene monomer.[3][4] The complex [(η5-C5H5)Ir(η4-C5H6)], the analogue of rhodocene derivative reported by Fischer,[3] has also been studied and demonstrates properties consistent with a greater degree of π-backbonding in iridium(I) systems than is found in the analogous cobalt(I) or rhodium(I) cases.[41]

Synthesis

Rhodocenium salts were first reported[11] within two years of the discovery of ferrocene.[10] These salts were prepared by reacting the carbanion Grignard reagent cyclopentadienylmagnesium bromide (C5H5MgBr) with tris(acetylacetonato)rhodium(III) (Rh(acac)3). More recently, gas-phase rhodocenium cations have been generated by a redox transmetalation reaction of rhodium(I) ions with ferrocene or nickelocene.[16]

- Rh+ + [(η5-C5H5)2M] → M + [(η5-C5H5)2Rh]+ M = Ni or Fe

Modern microwave synthetic methods have also been reported.[42] Rhodocenium hexafluorophosphate forms after reaction of cyclopentadiene and rhodium(III) chloride hydrate in methanol following work-up with methanolic ammonium hexafluorophosphate; the reaction yield exceeds 60% with only 30 seconds of exposure to microwave radiation.[43]

Rhodocene itself is then formed by reduction of rhodocenium salts with molten sodium.[3] If a rhodocenium containing melt is treated with sodium or potassium metals and then sublimed onto a liquid nitrogen-cooled cold finger, a black polycrystalline material results.[36] Warming this material to room temperature produces a yellow solid which has been confirmed as the rhodocene dimer. A similar method can be used to prepare the iridocene dimer.[36]

Substituted rhodocenes and rhodocenium salts

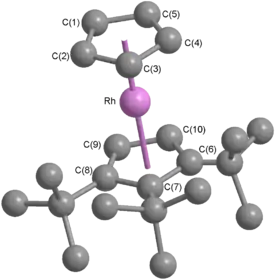

The [(η5-C5tBu3H2)Rh(η5-C5H5)]+ cation

Novel approaches to synthesising substituted cyclopentadienyl complexes have been developed using substituted vinylcyclopropene starting materials.[44][45][46] Ring-enlarging vinylcyclopropane rearrangement reactions to produce cyclopentenes are well known[47] and serve as precedent for vinylcyclopropenes rearranging to cyclopentadienes. The [(η5-C5tBu3H2)Rh(η5-C5H5)]+ cation has been generated by a reaction sequence beginning with addition of the chlorobisethylenerhodium(I) dimer, [(η2-C2H4)2Rh(μ-Cl)]2, to 1,2,3-tri-tert-butyl-3-vinyl-1-cyclopropene followed by reaction with thallium cyclopentadienide:[44][45]

The 18-valence electron rhodium(III) pentadienediyl species generated by this reaction demonstrates again the instability of the rhodocene moiety, in that it can be refluxed in toluene for months without 1,2,3-tri-tert-butylrhodocene forming but in oxidising conditions the 1,2,3-tri-tert-butylrhodocenium cation forms rapidly.[44] Cyclic voltammetry has been used to investigate this and similar processes in detail.[44][45] The mechanism of the reaction has been shown to involve a loss of one electron from the pentadienediyl ligand followed by a fast rearrangement (with loss of a hydrogen atom) to form the 1,2,3-tri-tert-butylrhodocenium cation.[45] Both the tetrafluoroborate and hexafluorophosphate salts of this cation have been structurally characterised by X-ray crystallography.[45]

[(η5-C5tBu3H2)Rh(η5-C5H5)]BF4 forms a colourless centrosymmetric monoclinic crystal belonging to the P21/c space group, and with a density of 1.486 g cm−3.[45] Looking at the ORTEP diagram of the structure of the cation (at right), it is evident that it possesses the typical geometry expected of a rhodocene or rhodocenium cation. The two cyclopentadienyl rings are close to parallel (the centroid–Rh–centroid angle is 177.2°) and the rhodium centre is slightly closer to the substituted cyclopentadienyl ring (Rh–centroid distances are 1.819 Å and 1.795 Å), an observation attributed to the greater inductive effect of the tert-butyl groups on the substituted ligand.[45] The ORTEP diagram shows that the cation adopts an eclipsed conformation in the solid state. The crystal structure of the hexafluorophosphate salt shows three crystallographically independent cations, one eclipsed, one staggered, and one which is rotationally disordered.[45] This suggests that the conformation adopted is dependent on the anion present and also that the energy barrier to rotation is low – in ferrocene, the rotational energy barrier is known to be ~5 kJ mol−1 in both solution and gas phase.[13]

Rh(C5H5))BF4.png.webp)

The diagram above shows the rhodium–carbon (in red, inside pentagons on the left) and carbon–carbon (in blue, outside pentagons on the left) bond distances for both ligands, along with the bond angles (in green, inside pentagons on the right) within each cyclopentadienyl ring. The atom labels used are the same as those shown in the crystal structure above. Within the unsubstituted cyclopentadienyl ligand, the carbon–carbon bond lengths vary between 1.35 Å and 1.40 Å and the internal bond angles vary between 107° and 109°. For comparison, the internal angle at each vertex of a regular pentagon is 108°. The rhodium–carbon bond lengths vary between 2.16 Å and 2.18 Å.[45] These results are consistent with η5-coordination of the ligand to the metal centre. In the case of the substituted cyclopentadienyl ligand, there is somewhat greater variation: carbon–carbon bond lengths vary between 1.39 Å and 1.48 Å, the internal bond angles vary between 106° and 111°, and the rhodium–carbon bond lengths vary between 2.14 Å and 2.20 Å. The greater variation in the substituted ligand is attributed to the distortions necessary to relieve the steric strain imposed by neighbouring tert-butyl substituents; despite these variations, the data demonstrate that the substituted cyclopentadienyl is also η5-coordinated.[45]

The stability of metallocenes changes with ring substitution. Comparing the reduction potentials of the cobaltocenium and decamethylcobaltocenium cations shows that the decamethyl species is ca. 600 mV more reducing than its parent metallocene,[19] a situation also observed in the ferrocene[48] and rhodocene systems.[49] The following data are presented relative to the ferrocenium / ferrocene redox couple:[50]

| Half-reaction | E° (V) |

|---|---|

| [Fe(C5H5)2]+ + e− ⇌ [Fe(C5H5)2] | 0 (by definition) |

| [Fe(C5Me5)2]+ + e− ⇌ [Fe(C5Me5)2] | −0.59[48] |

| [Co(C5H5)2]+ + e− ⇌ [Co(C5H5)2] | −1.33[19] |

| [Co(C5Me5)2]+ + e− ⇌ [Co(C5Me5)2] | −1.94[19] |

| [Rh(C5H5)2]+ + e− ⇌ [Rh(C5H5)2] | −1.79[1] † |

| [Rh(C5Me5)2]+ + e− ⇌ [Rh(C5Me5)2] | −2.38[49] |

| [(C5tBu3H2)Rh(C5H5)]+ + e− ⇌ [(C5tBu3H2)Rh(C5H5)] | −1.83[45] |

| [(C5tBu3H2)Rh(C5Me5)]+ + e− ⇌ [(C5tBu3H2)Rh(C5Me5)] | −2.03 [45] |

| [(C5H5Ir(C5Me5)]+ + e− ⇌ [(C5H5Ir(C5Me5)] | −2.41[51] † |

| [Ir(C5Me5)2]+ + e− ⇌ [Ir(C5Me5)2] | −2.65[51] † |

| † after correcting by 0.38 V[34] for the different standard |

The differences in reduction potentials is attributed in the cobaltocenium system to the inductive effect of the alkyl groups,[19] further stabilising the 18-valence electron species. A similar effect is seen in the rhodocenium data shown above, again consistent with inductive effects.[45] In the substituted iridocenium system, cyclic voltammetry investigations shows irreversible reductions at temperatures as low as −60 °C;[51] by comparison, the reduction of the corresponding rhodocenes is quasi-reversible at room temperature and fully reversible at −35 °C.[49] The irreversibility of the substituted iridocenium reductions is attributed to the extremely rapid dimerisation of the resulting 19-valence electron species, which further illustrates that iridocenes are less stable than their corresponding rhodocenes.[51]

Pentasubstituted cyclopentadienyl ligands

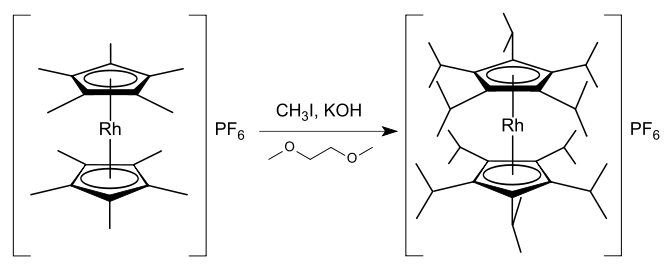

The body of knowledge concerning compounds with penta-substituted cyclopentadienyl ligands is extensive, with organometallic complexes of the pentamethylcyclopentadienyl and pentaphenylcyclopentadienyl ligands being well-known.[52] Substitutions on the cyclopentadienyl rings of rhodocenes and rhodocenium salts produce compounds of higher stability as they allow for the increased delocalisation of positive charge or electron density and also provide steric hindrance against other species approaching the metal centre.[37] Various mono- and di-substituted rhodocenium species are known, but substantial stabilisation is not achieved without greater substitutions.[37] Known highly substituted rhodocenium salts include decamethylrhodocenium hexafluorophosphate [(η5-C5Me5)2Rh]PF6,[53] decaisopropylrhodocenium hexafluorophosphate [(η5-C5iPr5)2Rh]PF6,[54] and octaphenylrhodocenium hexafluorophosphate [(η5-C5Ph4H)2Rh]PF6.[18][Note 5] Decamethylrhodocenium tetrafluoroborate can be synthesised from the tris(acetone) complex [(η5-C5Me5)Rh(Me2CO)3](BF4)2 by reaction with pentamethylcyclopentadiene, and the analogous iridium synthesis is also known.[55] Decaisopropylrhodicnium hexafluorophosphate was synthesised in 1,2-dimethoxyethane (solvent) in an unusual one-pot synthesis that involves the formation of 20 carbon–carbon bonds:[54]

In a similar reaction, pentaisopropylrhodocenium hexafluorophosphate [(η5-C5iPr5)Rh(η5-C5H5)]PF6 can be synthesised from pentamethylrhodocenium hexafluorophosphate [(η5-C5Me5)Rh(η5-C5H5)]PF6 in 80% yield.[54] These reactions demonstrate that the acidity of the methyl hydrogens in a pentamethylcyclopentadienyl complex can be considerably increased by the presence of the metal centre. Mechanistically, the reaction proceeds with potassium hydroxide deprotonating a methyl group and the resulting carbanion undergoing nucleophilic substitution with methyl iodide to form a new carbon–carbon bond.[54]

The compounds pentaphenylrhodocenium tetrafluoroborate [(η5-C5Ph5)Rh(η5-C5H5)]BF4, and pentamethylpentaphenylrhodocenium tetrafluoroborate [(η5-C5Ph5)Rh(η5-C5Me5)]BF4 have also been reported. They demonstrate that rhodium sandwich compounds can be prepared from half-sandwich precursors. For example, in an approach broadly similar to the tris(acetone) synthesis of decamethylrhodocenium tetrafluoroborate,[55] pentaphenylrhodocenium tetrafluoroborate has been synthesised from the tris(acetonitrile) salt [(η5-C5Ph5)Rh(CH3CN)3](BF4)2 by reaction with sodium cyclopentadienide:[17]

- [(η5-C5Ph5)Rh(MeCN)3](BF4)2 + NaC5H5 → [(η5-C5Ph5)Rh(η5-C5H5)]BF4 + NaBF4 + 3 MeCN

Octaphenylrhodocene, [(η5-C5Ph4H)2Rh], is the first rhodocene derivative to be isolated at room temperature. Its olive green crystals decompose rapidly in solution, and within minutes in air, demonstrating a dramatically greater air sensitivity than the analogous cobalt complex, although it is significantly more stable than rhodocene itself. This difference is attributed to the relatively lower stability of the rhodium(II) state as compared to the cobalt(II) state.[18][38] The reduction potential for the [(η5-C5Ph4H)2Rh]+ cation (measured in dimethylformamide relative the ferrocenium / ferrocene couple) is −1.44 V, consistent with the greater thermodynamic stabilisation of the rhodocene by the C5HPh4 ligand compared with the C5H5 or C5Me5 ligands.[18] Cobaltocene is a useful one-electron reducing agent in the research laboratory as it is soluble in non-polar organic solvents,[19] and its redox couple is sufficiently well behaved that it may be used as an internal standard in cyclic voltammetry.[56] No substituted rhodocene yet prepared has demonstrated sufficient stability to be used in a similar way.

The synthesis of octaphenylrhodocene proceeds in three steps, with a diglyme reflux followed by workup with hexafluorophosphoric acid, then a sodium amalgam reduction in tetrahydrofuran:[18]

- Rh(acac)3 + 2 KC5Ph4H → [(η5-C5Ph4H)2Rh]+ + 2 K+ + 3 acac−

- [(η5-C5Ph4H)2Rh]+ + 3 acac− + 3 HPF6 → [(η5-C5Ph4H)2Rh]PF6 + 3 Hacac + 2 PF6−

- [(η5-C5Ph4H)2Rh]PF6 + Na/Hg → [(η5-C5Ph4H)2Rh] + NaPF6

The crystal structure of octaphenylrhodocene shows a staggered conformation[18] (similar to that of ferrocene, and in contrast to the eclipsed conformation of ruthenocene).[13] The rhodium–centroid distance is 1.904 Å and the rhodium–carbon bond lengths average 2.26 Å; the carbon–carbon bond lengths average 1.44 Å.[18] These distances are all similar to those found in the 1,2,3-tri-tert-butylrhodocenium cation described above, with the one difference that the effective size of the rhodium centre appears larger, an observation consistent with the expanded ionic radius of rhodium(II) compared with rhodium(III).

Applications

Biomedical use of a derivative

There has been extensive research into metallopharmaceuticals,[57][58] including discussion of rhodium compounds in medicine.[20] A substantial body of research has examined using metallocene derivatives of ruthenium[59] and iron[60] as metallopharmaceuticals. One area of such research has utilised metallocenes in place of the fluorophenyl group in haloperidol,[21] which is a pharmaceutical classified as a typical antipsychotic. The ferrocenyl–haloperidol compound investigated has structure (C5H5)Fe(C5H4)–C(=O)–(CH2)3–N(CH2CH2)2C(OH)–C6H4Cl and can be converted to the ruthenium analog via a transmetalation reaction. Using the radioactive isotope 103Ru produces a ruthenocenyl–haloperidol radiopharmaceutical with a high affinity for lung but not brain tissue in mice and rats.[21] Beta-decay of 103Ru produces the metastable isotope 103mRh in a rhodocenyl–haloperidol compound. This compound, like other rhodocene derivatives, has an unstable 19-valence electron configuration and rapidly oxidises to the expected cationic rhodocenium–haloperidol species.[21] The separation of the ruthenocenyl–haloperidol and the rhodocenium–haloperidol species and the distributions of each amongst bodily organs has been studied.[22] 103mRh has a half-life of 56 min and emits a gamma ray of energy 39.8 keV, so the gamma-decay of the rhodium isotope should follow soon after the beta-decay of the ruthenium isotope. Beta- and gamma-emitting radionuclides used medically include 131I, 59Fe, and 47Ca, and 103mRh has been proposed for use in radiotherapy for small tumours.[20]

Metal–metal interactions in linked metallocenes

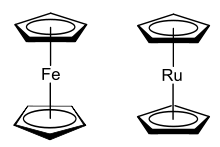

The original motivation for research investigations of the rhodocene system was to understand the nature of and bonding within the metallocene class of compounds. In more recent times, interest has been rekindled by the desire to explore and apply the metal–metal interactions that occur when metallocene systems are linked.[23] Potential applications for such systems include molecular electronics,[24] semi-conducting (and possibly ferromagnetic) metallocene polymers (an example of a molecular wire),[23] and exploring the threshold between heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis.[24] Examples of known bimetallocenes and termetallocenes that possess the rhodocenyl moiety include the hexafluorophosphate salts of rhodocenylferrocene, 1,1'-dirhodocenylferrocene, and 1-cobaltocenyl-1'-rhodocenylferrocene,[61] each shown at right. Linked metallocenes can also be formed by introducing several metallocenyl substituents onto a single cyclopentadienyl ligand.[24]

Structural studies of termetallocene systems have shown they typically adopt an "eclipsed double transoid" "crankshaft" geometry.[62] Taking as an example the 1-cobaltocenyl-1'-rhodocenylferrocene cation shown above, this means that the cobaltocenyl and rhodocenyl moieties are eclipsed, and thus carbon atoms 1 and 1' on the central ferrocene core are as close to vertically aligned as is possible given the staggered conformation of the cyclopentadienyl rings within each metallocene unit. Viewed from side-on, this means termetallocenes resemble the down–up–down pattern of a crankshaft.[62] The synthesis of this termetallocene involves the combining of rhodocenium and cobaltocenium solutions with 1,1'-dilithioferrocene. This produces an uncharged intermediate with linked cyclopentadienyl–cyclopentadiene ligands whose bonding resembles that found in the rhodocene dimer. These ligands then react with the triphenylmethyl carbocation to generate the termetallocene salt, [(η5-C5H5)Rh(μ-η5:η5-C5H4–C5H4)Fe(μ-η5:η5-C5H4–C5H4)Co(η5-C5H5)](PF6)2. This synthetic pathway is illustrated below:[61][62]

Rhodocenium-containing polymers

The first rhodocenium-containing side-chain polymers were prepared through controlled polymerization techniques such as reversible addition−fragmentation chain-transfer polymerization (RAFT) and ring-opening metathesis polymerisation (ROMP).[63]

Notes

- The 18-valence electron cation [Rh(C5H5)2]+ is called the rhodocenium cation in some journal articles[1] and the rhodicinium cation in others.[11] The former spelling appears more common in more recent literature and so is adopted in this article, but both formulations refer to the same chemical species.

- The presence of a mirror plane perpendicular to the C5 ring centroid–metal–ring centroid axis of symmetry suggests an eclipsed rather than a staggered conformation. Free rotation of cyclopentadienyl ligands about this axis is common in metallocenes – in ferrocene, the energy barrier to rotation is ~5 kJ mol−1.[13] Consequently, there would be both staggered and eclipsed rhodocene monomer molecules co-existing, and rapidly interconverting, in the solution. It is only in the solid state that a definitive assignment of staggered or eclipsed conformation is really meaningful.

- In the rhodocene dimer, the joined cyclopentadiene rings are shown with the H atoms in the "endo" position (i.e. the H's are inside, the other half of the ligands are on the outside). Although this is not based on crystal structure data, it does follow the illustrations provided by El Murr et al.[1] and by Fischer and Wawersik[3] in their discussion of the 1H NMR data they collected. The paper by Collins et al.,[18] shows the H atoms in the "exo" position.

- There are two distinct approaches to electron counting, based on either radical species or ionic species. Using the radical approach, a rhodium centre has 9 electrons irrespective of its oxidation states and a cyclopentadienyl ligand is a 5 electron donor. Using the ionic approach, the cyclopentadienyl ligand is a 6 electron donor and the electron count of the rhodium centre depends on its oxidation state – rhodium(I) is an 8 electron centre, rhodium(II) is a 7 electron centre, and rhodium(III) is a 6 electron centre. The two approaches generally reach the same conclusions but it is important to be consistent in using only one or the other.

- There are common abbreviations used for molecular fragments in chemical species: "Me" stands for the methyl group, —CH3; "iPr" stands for the iso-propyl group, —CH(CH3)2; "Ph" stands for the phenyl group, —C6H5; "tBu" stands for the tert-butyl group, —C(CH3)3.

References

- El Murr, N.; Sheats, J. E.; Geiger, W. E.; Holloway, J. D. L. (1979). "Electrochemical Reduction Pathways of the Rhodocenium Ion. Dimerization and Reduction of Rhodocene". Inorganic Chemistry. 18 (6): 1443–1446. doi:10.1021/ic50196a007.

- Crabtree, R. H. (2009). The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-470-25762-3.

An industrial application of transition metal organometallic chemistry appeared as early as the 1880s, when Ludwig Mond showed that nickel can be purified by using CO to pick up nickel in the form of gaseous Ni(CO)4 that can easily be separated from solid impurities and later be thermally decomposed to give pure nickel.

... Recent work has shown the existence of a growing class of metalloenzymes having organometallic ligand environments – considered as the chemistry of metal ions having C-donor ligands such as CO or the methyl group

- Fischer, E. O.; Wawersik, H. (1966). "Über Aromatenkomplexe von Metallen. LXXXVIII. Über Monomeres und Dimeres Dicyclopentadienylrhodium und Dicyclopentadienyliridium und Über Ein Neues Verfahren Zur Darstellung Ungeladener Metall-Aromaten-Komplexe" [Aromatic Complexes of Metals. LXXXVIII. On the Monomers and Dimers Dicyclopentadienylrhodium and Dicyclopentadienyliridium and a New Method for the Preparation of Uncharged Metal-Aromatic Complexes]. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry (in German). 5 (6): 559–567. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)85160-8.

- Keller, H. J.; Wawersik, H. (1967). "Spektroskopische Untersuchungen an Komplexverbindungen. VI. EPR-spektren von (C5H5)2Rh und (C5H5)2Ir" [Spectroscopic studies of complex compounds. VI. EPR spectra of (C5H5)2Rh and (C5H5)2Ir]. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry (in German). 8 (1): 185–188. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)84718-X.

- Zeise, W. C. (1831). "Von der Wirkung zwischen Platinchlorid und Alkohol, und von den dabei entstehenden neuen Substanzen" [On the interaction between platinum chloride and alcohol, and the new substances thereby formed]. Annalen der Physik (in German). 97 (4): 497–541. Bibcode:1831AnP....97..497Z. doi:10.1002/andp.18310970402.

- Hunt, L. B. (1984). "The First Organometallic Compounds: William Christopher Zeise and his Platinum Complexes" (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 28 (2): 76–83.

- Winterton, N. (2002). "Some Notes on the Early Development of Models of Bonding in Olefin-Metal Complexes". In Leigh, G. J.; Winterton, N. (eds.). Modern Coordination Chemistry: The Legacy of Joseph Chatt. RSC Publishing. pp. 103–110. ISBN 9780854044696.

- Laszlo, P.; Hoffmann, R. (2000). "Ferrocene: Ironclad History or Rashomon Tale?". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 39 (1): 123–124. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<123::AID-ANIE123>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10649350.

- Federman Neto, A.; Pelegrino, A. C.; Darin, V. A. (2004). "Ferrocene: 50 Years of Transition Metal Organometallic Chemistry — From Organic and Inorganic to Supramolecular Chemistry". ChemInform. 35 (43). doi:10.1002/chin.200443242. (Abstract; original published in Trends in Organometallic Chemistry, 4:147–169, 2002)

- Kealy, T. J.; Pauson, P. L. (1951). "A New Type of Organo-Iron Compound". Nature. 168 (4285): 1039–1040. Bibcode:1951Natur.168.1039K. doi:10.1038/1681039b0. S2CID 4181383.

- Cotton, F. A.; Whipple, R. O.; Wilkinson, G. (1953). "Bis-Cyclopentadienyl Compounds of Rhodium(III) and Iridium(III)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 75 (14): 3586–3587. doi:10.1021/ja01110a504.

- Mingos, D. M. P. (2001). "A Historical Perspective on Dewar's Landmark Contribution to Organometallic Chemistry". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 635 (1–2): 1–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(01)01155-X.

- Mehrotra, R. C.; Singh, A. (2007). Organometallic Chemistry: A Unified Approach (2nd ed.). New Delhi: New Age International. pp. 261–267. ISBN 978-81-224-1258-1.

- "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1973". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- Sherwood, Martin (1 November 1973). "Metal Sandwiches". New Scientist. 60 (870): 335. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- Jacobson, D. B.; Byrd, G. D.; Freiser, B. S. (1982). "Generation of Titanocene and Rhodocene Cations in the Gas Phase by a Novel Metal-Switching Reaction". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 104 (8): 2320–2321. doi:10.1021/ja00372a041.

- He, H. T. (1999). Synthesis and Characterisation of Metallocenes Containing Bulky Cyclopentadienyl Ligands (PhD thesis). University of Sydney. OCLC 222646266.

- Collins, J. E.; Castellani, M. P.; Rheingold, A. L.; Miller, E. J.; Geiger, W. E.; Rieger, A. L.; Rieger, P. H. (1995). "Synthesis, Characterization, and Molecular-Structure of Bis(tetraphenylcyclopentadienyl)rhodium(II)". Organometallics. 14 (3): 1232–1238. doi:10.1021/om00003a025.

- Connelly, N. G.; Geiger, W. E. (1996). "Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry". Chemical Reviews. 96 (2): 877–910. doi:10.1021/cr940053x. PMID 11848774.

- Pruchnik, F. P. (2005). "45Rh — Rhodium in Medicine". In Gielen, M.; Tiekink, E. R. T (eds.). Metallotherapeutic Drugs and Metal-Based Diagnostic Agents: The Use of Metals in Medicine. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 379–398. doi:10.1002/0470864052.ch20. ISBN 0-470-86403-6.

- Wenzel, M.; Wu, Y. (1988). "Ferrocen-, Ruthenocen-bzw. Rhodocen-analoga von Haloperidol Synthese und Organverteilung nach Markierung mit 103Ru-bzw. 103mRh" [Ferrocene, ruthenocene and rhodocene analogs in haloperidol synthesis and organ distribution after labeling with 103Ru and 103mRh]. International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation A (in German). 39 (12): 1237–1241. doi:10.1016/0883-2889(88)90106-2. PMID 2851003.

- Wenzel, M.; Wu, Y. F. (1987). "Abtrennung von [103mRh]Rhodocen-Derivaten von den Analogen [103Ru]Ruthenocen-Derivaten und deren Organ-Verteilung" [Separation of [103mRh]rhodocene derivatives from the parent [103Ru]ruthenocene derivatives and their organ distribution]. International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation A (in German). 38 (1): 67–69. doi:10.1016/0883-2889(87)90240-1. PMID 3030970.

- Barlow, S.; O'Hare, D. (1997). "Metal–Metal Interactions in Linked Metallocenes". Chemical Reviews. 97 (3): 637–670. doi:10.1021/cr960083v. PMID 11848884.

- Wagner, M. (2006). "A New Dimension in Multinuclear Metallocene Complexes". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 45 (36): 5916–5918. doi:10.1002/anie.200601787. PMID 16906602.

- Black, M.; Mais, R. H. B.; Owston, P. G. (1969). "The crystal and molecular structure of Zeise's salt, KPtCl3.C2H4.H2O". Acta Crystallographica B. 25 (9): 1753–1759. doi:10.1107/S0567740869004699.

- Jarvis, J. A. J.; Kilbourn, B. T.; Owston, P. G. (1971). "A Re-determination of the Crystal and Molecular Structure of Zeise's salt, KPtCl3.C2H4.H2O". Acta Crystallographica B. 27 (2): 366–372. doi:10.1107/S0567740871002231.

- Leigh, G. J.; Winterton, N., eds. (2002). "Section D: Transition Metal Complexes of Olefins, Acetylenes, Arenes and Related Isolobal COmpounds". Modern Coordination Chemistry: The Legacy of Joseph Chatt. Cambridge, UK: RSC Publishing. pp. 101–110. ISBN 0-85404-469-8.

- Mingos, D. Michael P. (2001). "A Historical Perspective on Dewar's Landmark Contribution to Organometallic Chemistry". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 635 (1–2): 1–8. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(01)01155-X.

- Astruc, D. (2007). Organometallic Chemistry and Catalysis. Berlin: Springer. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-3-540-46128-9.

- Wilkinson, G.; Rosenblum, M.; Whiting, M. C.; Woodward, R. B. (1952). "The Structure of Iron Bis-Cyclopentadienyl". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 74 (8): 2125–2126. doi:10.1021/ja01128a527.

- Werner, H. (2008). Landmarks in Organo-Transition Metal Chemistry: A Personal View. New York: Springer Science. pp. 161–163. ISBN 978-0-387-09847-0.

- Fischer, E. O.; Pfab, W. (1952). "Zur Kristallstruktur der Di-Cyclopentadienyl-Verbindungen des zweiwertigen Eisens, Kobalts und Nickels" [On the crystal structure of the dicyclopentadienyl compounds of divalent iron, cobalt and nickel]. Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie (in German). 7 (6): 377–379. doi:10.1002/zaac.19532740603.

- Eiland, P. F.; Pepinsky, R. (1952). "X-ray Examination of Iron Biscyclopentadienyl". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 74 (19): 4971. doi:10.1021/ja01139a527.

- Pavlishchuk, V. V.; Addison, A. W. (2000). "Conversion Constants for Redox Potentials Measured Versus Different Reference Electrodes in Acetonitrile Solutions at 25 °C". Inorganica Chimica Acta. 298 (1): 97–102. doi:10.1016/S0020-1693(99)00407-7.

- Kotz, J. C.; Treichel, P. M.; Townsend, J. R. (2009). Chemistry and Chemical Reactivity, Volume 2 (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. pp. 1050–1053. ISBN 978-0-495-38703-9.

- De Bruin, B.; Hetterscheid, D. G. H.; Koekkoek, A. J. J.; Grützmacher, H. (2007). "The Organometallic Chemistry of Rh–, Ir–, Pd–, and Pt–Based Radicals: Higher Valent Species". Progress in Inorganic Chemistry. 55: 247–354. doi:10.1002/9780470144428.ch5. ISBN 978-0-471-68242-4.

- Zagorevskii, D. V.; Holmes, J. L. (1992). "Observation of Rhodocenium and Substituted-Rhodocenium Ions and their Neutral Counterparts by Mass Spectrometry". Organometallics. 11 (10): 3224–3227. doi:10.1021/om00046a018.

- Cotton, S. A. (1997). "Rhodium and Iridium". Chemistry of Precious Metals. London: Blackie Academic and Professional. pp. 78–172. ISBN 0-7514-0413-6.

Both metals exhibit an extensive chemistry, principally in the +3 oxidation state, with +1 also being important, and a significant chemistry of +4 iridium existing. Few compounds are known in the +2 state, in contrast to the situation for cobalt, their lighter homologue (factors responsible include the increased stability of the +3 state consequent upon the greater stabilization of the low spin d6 as 10 Dq increases)." (p. 78)

- Hill, A. F. (2002). Organotransition Metal Chemistry. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 4–7. ISBN 0-85404-622-4.

- Green, M. L. H.; Pratt, L.; Wilkinson, G. (1959). "760. A New Type of Transition Metal–Cyclopentadiene Compound". Journal of the Chemical Society: 3753–3767. doi:10.1039/JR9590003753.

- Szajek, L. P.; Shapley, J. R. (1991). "Unexpected Synthesis of CpIr(η4-C5H6) and a Proton and Carbon-13 NMR Comparison with its Cobalt and Rhodium Congeners". Organometallics. 10 (7): 2512–2515. doi:10.1021/om00053a066.

- Baghurst, D. R.; Mingos, D. M. P. (1990). "Design and Application of a Reflux Modification for the Synthesis of Organometallic Compounds Using Microwave Dielectric Loss Heating Effects". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 384 (3): C57–C60. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(90)87135-Z.

- Baghurst, D. R.; Mingos, D. M. P.; Watson, M. J. (1989). "Application of Microwave Dielectric Loss Heating Effects for the Rapid and Convenient Synthesis of Organometallic Compounds". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 368 (3): C43–C45. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(89)85418-X.

- Donovan-Merkert, B. T.; Tjiong, H. I.; Rhinehart, L. M.; Russell, R. A.; Malik, J. (1997). "Facile, Redox-Promoted Formation of Rhodocenium Complexes Bearing the 1,2,3-Tri-tert-butylcyclopentadienyl Ligan". Organometallics. 16 (5): 819–821. doi:10.1021/om9608871.

- Donovan-Merkert, B. T.; Clontz, C. R.; Rhinehart, L. M.; Tjiong, H. I.; Carlin, C. M.; Cundari, Thomas R.; Rheingold, Arnold L.; Guzei, Ilia (1998). "Rhodocenium Complexes Bearing the 1,2,3-Tri-tert-butylcyclopentadienyl Ligand: Redox-Promoted Synthesis and Mechanistic, Structural and Computational Investigations". Organometallics. 17 (9): 1716–1724. doi:10.1021/om9707735.

- Hughes, R. P.; Trujillo, H. A.; Egan, J. W.; Rheingold, A. L. (1999). "Skeletal Rearrangement during Rhodium-Promoted Ring Opening of 1,2-Diphenyl-3-vinyl-1-cyclopropene. Preparation and Characterization of 1,2- and 2,3-Diphenyl-3,4-pentadienediyl Rhodium Complexes and Their Ring Closure to a 1,2-Diphenylcyclopentadienyl Complex". Organometallics. 18 (15): 2766–2772. doi:10.1021/om990159o.

- Goldschmidt, Z.; Crammer, B. (1988). "Vinylcyclopropane Rearrangements". Chemical Society Reviews. 17: 229–267. doi:10.1039/CS9881700229.

- Noviandri, I.; Brown, K. N.; Fleming, D. S.; Gulyas, P. T.; Lay, P. A.; Masters, A. F.; Phillips, L. (1999). "The Decamethylferrocenium/Decamethylferrocene Redox Couple: A Superior Redox Standard to the Ferrocenium/Ferrocene Redox Couple for Studying Solvent Effects on the Thermodynamics of Electron Transfer". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 103 (32): 6713–6722. doi:10.1021/jp991381+.

- Gusev, O. V.; Denisovich, L. I.; Peterleitner, M. G.; Rubezhov, A. Z.; Ustynyuk, Nikolai A.; Maitlis, P. M. (1993). "Electrochemical Generation of 19- and 20-electron Rhodocenium Complexes and Their Properties". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 452 (1–2): 219–222. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(93)83193-Y.

- Gagne, R. R.; Koval, C. A.; Lisensky, G. C. (1980). "Ferrocene as an Internal Standard for Electrochemical Measurements". Inorganic Chemistry. 19 (9): 2854–2855. doi:10.1021/ic50211a080.

- Gusev, O. V.; Peterleitner, M. G.; Ievlev, M. A.; Kal'sin, A. M.; Petrovskii, P. V.; Denisovich, L. I.; Ustynyuk, Nikolai A. (1997). "Reduction of Iridocenium Salts [Ir(η5-C5Me5)(η5-L)]+ (L= C5H5, C5Me5, C9H7); Ligand-to-Ligand Dimerisation Induced by Electron Transfer". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 531 (1–2): 95–100. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(96)06675-2.

- Okuda, J. (1992). "Transition-Metal Complexes of Sterically Demanding Cyclopentadienyl Ligands". In W. A., Herrmann (ed.). Transition Metal Coordination Chemistry. Topics in Current Chemistry. 160. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 97–145. doi:10.1007/3-540-54324-4_3. ISBN 3-540-54324-4.

- Kölle, U.; Kläui, W. Z.l (1991). "Darstellung und Redoxverhalten einer Serie von Cp*/aqua/tripod-Komplexen des Co, Rh und Ru" [Preparation and redox behaviour of a series of Cp* / water / tripod complexes of Co, Rh and Ru]. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B (in German). 46 (1): 75–83. doi:10.1515/znb-1991-0116. S2CID 95222717.

- Buchholz, D.; Astruc, D. (1994). "The First Decaisopropylmetallocene – One-Pot Synthesis of [Rh(C5iPr5)2]PF6 from [Rh(C5Me5)2]PF6 by Formation of 20 Carbon–Carbon Bonds". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 33 (15–16): 1637–1639. doi:10.1002/anie.199416371.

- Gusev, O. V.; Morozovaa, L. N.; Peganovaa, T. A.; Petrovskiia, P. V.; Ustynyuka N. A.; Maitlis, P. M. (1994). "Synthesis of η5-1,2,3,4,5-Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl-Platinum Complexes". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 472 (1–2): 359–363. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(94)80223-8.

- Stojanovic, R. S.; Bond, A. M. (1993). "Examination of Conditions under which the Reduction of the Cobaltocenium Cation can be used as a Standard Voltammetric Reference Process in Organic and Aqueous Solvents". Analytical Chemistry. 65 (1): 56–64. doi:10.1021/ac00049a012.

- Clarke, M. J.; Sadler, P. J. (1999). Metallopharmaceuticals: Diagnosis and therapy. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-65308-2.

- Jones, C. J.; Thornback, J. (2007). Medicinal Applications of Coordination Chemistry. Cambridge, UK: RSC Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85404-596-9.

- Clarke, M. J. (2002). "Ruthenium Metallopharmaceuticals". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 232 (1–2): 69–93. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00025-5.

- Fouda, M. F. R.; Abd-Elzaher, M. M.; Abdelsamaia, R. A.; Labib, A. A. (2007). "On the Medicinal Chemistry of Ferrocene". Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 21 (8): 613–625. doi:10.1002/aoc.1202.

- Andre, M.; Schottenberger, H.; Tessadri, R.; Ingram, G.; Jaitner, P.; Schwarzhans, K. E. (1990). "Synthesis and Preparative HPLC-Separation of Heteronuclear Oligometallocenes. Isolation of Cations of Rhodocenylferrocene, 1,1'-Dirhodocenylferrocene, and 1-Cobaltocenyl-1'-rhodocenylferrocene". Chromatographia. 30 (9–10): 543–545. doi:10.1007/BF02269802. S2CID 93898229.

- Jaitner, P.; Schottenberger, H.; Gamper, S.; Obendorf, D. (1994). "Termetallocenes". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 475 (1–2): 113–120. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(94)84013-X.

- Yan, Y.; Deaton, T. M.; Zhang, J.; Hongkun, H.; Hayat, J.; Pageni, P.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Tang, C. (2015). "The Syntheses of Monosubstituted Rhodocenium Derivatives, Monomers and Polymers". Macromolecules. 48 (6): 1644–1650. Bibcode:2015MaMol..48.1644Y. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00471.

Rh(C5H5))BF4.svg.png.webp)